Abstract

New rapid growth economies, urbanization, health systems crises and “big data” are causing fundamental changes in social structures and systems including health. These forces for change have significant consequences for occupational and environmental medicine and will challenge the specialty to think beyond workers and workplaces as the principal locus of innovation for health and performance. These trends are placing great emphasis on upstream strategies for addressing the complex systems dynamics of the social determinants of health. The need to engage systems in communities for healthier workforces is a shift in orientation from worker and workplace centric to citizen and community centric. This change for occupational and environmental medicine requires extending systems approaches in the workplace to communities which are systems of systems and which require different skills, data, tools and partnerships.

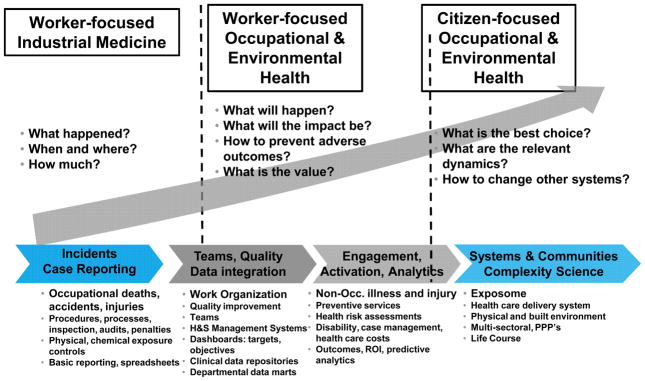

Occupational and environmental medicine is based on a population health and environmental paradigm of using data for understanding patterns and distributions and for predicting exposures, risks and outcomes. During the last century, major changes in materials (e.g. chemicals, radiation), people (e.g. demographics, skills), processes (e.g. assembly line, automation), laws (e.g. child labor, work hours, safety), and science and technologies (e.g. electrification, transportation, communications and computing) altered the nature of work on multiple occasions. 1, 2 These transformations expanded the opportunity for occupational and environmental medicine to perform new services with added value to workers and employers beyond providing acute medical care for workplace injuries and diseases. (Figure 1) New services included improved approaches to prevention of occupational morbidity and mortality such as training, exposure monitoring and control, risk assessment, screening, wellness and behavioral health interventions, disability management and rigorous health and safety management systems. More recently, longitudinal data collection on occupational and environmental exposures, economic and population health data and analytics are identifying new opportunities to support prevention, environmentally sustainable operations and returns on investments in health and safety.3

Figure 1.

From Worker To Citizen Health

The purpose of this commentary is to explore a subset of major disruptive forces for change and discuss how these may influence the practice of occupational and environmental medicine and perhaps shift its focus from worker and workplace to citizen and community. The forces for societal change discussed are the rapid economic development in emerging economies, health care delivery system transformations, noncommunicable diseases and massive data generation (big data) along with advances in information and communication technologies. (Figure 1) These forces will likely cause the next shift in occupational and environmental medicine’s opportunity for value creation, here defined as healthier environments, better health, higher productivity and competitive labor costs. While the physician is the prime focus of the commentary, other health and safety professionals will be affected in a similar fashion.

Disruptive Forces

Disruptive forces are affecting society and health through complex interactions and are challenging health systems and health professionals at unprecedented scale and speed.

1 Rapid growth economies

One such force is global economic development. Rapid economic growth has shifted from high income countries like the United States and Germany to middle income countries (MIC) such as China, India and South Africa.4, 5 This has caused major changes in the market focus for global and domestic corporations including the sizes and locations of their operations in these MIC countries. Rapid growth MIC countries present complicated admixtures of low income country (e.g. Chad, Cambodia and Bangladesh) and high income country health, environmental and safety challenges. For example, MIC countries share many of the following health problems with low income countries: poor access to basic medical care and essential drugs, effective communicable disease control, adequacy of essential public health services related to water, hygiene, sanitation, maternal and child health, unsafe sex and indoor smoke from solid fuels. Problems of high income countries are now also beginning to appear in MIC income countries. These often include violence, tobacco, alcohol and substance abuse, behavioral health, noncommunicable diseases and environmental contamination from toxic discharges. A decade ago, occupational and environmental professionals in a limited number of industries such as textile, energy and petrochemicals were challenged by occupational and public health threats in low and middle income countries. Today these are priorities for occupational and environmental medicine professionals in all major industries ranging from agriculture and construction to information technology and telecommunications since all are present in middle income country markets.

2 Urbanization

Changes in the distribution of the world’s population between rural and urban are also causing major disruptions in society and in health, creating additional opportunities for value from occupational and environmental medicine services. Urbanization is reshaping societies worldwide. Today more than half the world’s population lives in cities, and each week approximately 1.5 million more people are added to the urban population.6 It is projected that between 2011 and 2050 the global urban population will grow from 52% to 67% of the world’s population. This massive urban growth will be driven primarily from increases in less developed regions (from 47% to 64%) than from increases in the developed world (78% to 86%).7 Urbanization is advantageous for economic development by increasing paid labor opportunities and by concentrating people for more efficient services delivery such as education, health care and transportation. Often, however, poor urban planning, limited resources, corruption and other factors create urban conditions for slums, air pollution and excessive noise, poor built environments (e.g. walkability), low nutritional value food sources, violence and crime, drug trafficking and sexual exploitation and disease transmission.8 These urbanization hazards can impede economic development in cities and produce major adverse impacts on the health, productivity and costs of employed populations. Examples of such impacts include absenteeism, presenteeism, reduced flexibility due to transport or public safety, density related communicable disease transmission or rates of high cost chronic conditions such as HIV, hypertension, diabetes and depression.

3 Noncommunicable diseases

Noncommunicable diseases are adversely impacting economies, governments and the private sector. These conditions are challenging existing systems and structures for health care delivery, wellness and care management as well as economic development.9 Noncommunicable diseases accounted for 63% of global mortality in 2008 affecting 36 million individuals of which 25% or 9 million were in the working ages under 60 years old.10 Noncommunicable diseases cause 86% of healthy years of life lost in high income countries, 65% in middle income countries and 35% in low income countries due to its impact on premature death and disability (DALY –disability adjusted life years).11 While DALY from noncommunicable diseases will grow only 2.3% in high income countries between 2008 and 2030, it will increase during this period by 17% in middle income countries and 49% in low income countries.11

The cost of noncommunicable diseases is staggering. In the United States, noncommunicable diseases account for more than three quarters of all national health expenditures which are expected to increase from 17.8% of gross domestic product GDP (USD$2.76 trillion) in 2013 to 19.6% of GDP (USD$4.53 trillion) by 2021.12 Annual executive survey data in the private sector reveal that half of executive leaders perceive noncommunicable diseases as a direct threat to their bottom line in the next five years and a bigger business threat than communicable diseases including HIV/AIDs, tuberculosis and malaria.8

Noncommunicable diseases are known to be related to addressable risk factors including tobacco use, physical inactivity, low nutritional diets, obesity, excess alcohol consumption, and exposure to environmental pollution. Many of these risk factors and others have been shown in two landmark occupational and environmental medicine studies to account for 22% to 25% of total health care expenditures in the companies studied.13, 14 Currently, occupational and environmental medicine workforce strategies to mitigate these noncommunicable diseases risks are employee-focused programs and services. While this approach can be cost beneficial when high quality wellness and health promotion interventions are delivered, the long term maintenance of healthy behavior, improved health status and cost control are unknown with this approach alone.15 The challenge of durable risk modification is related to the determinants of risk for noncommunicable diseases which are outcomes of complex interactions involving people in socio-environmental systems of which the workplace is only one subsystem. Education, food sources, housing, the built environment, social networks and families, the media and other subsystems interact continuously to influence healthy or unhealthy behaviors. Noncommunicable diseases challenge occupational and environmental medicine to redesign strategies for prevention and care management around communities in order to help impact the root determinants of risk.

4 Health care delivery system transformation

Health care delivery system crises of cost, access, equity and quality are causing significant changes in the organization, technology, financing and delivery of care. This transformation will affect occupational and environmental medicine strategies for healthy workforces as well as occupational and environmental medicine skills and job functions. In the United States, changes to the organization of health services are well underway to shift from episodic fragmented medical care to comprehensive and coordinated care with outcomes based payment. “Medical homes” for primary care and “accountable care organizations” (ACO) are two examples of current initiatives to accomplish this shift. In primary care “medical homes”, physician led teams are organized to provide enhanced access, comprehensiveness, coordination and person- centered care.16 ACOs are organizations of integrated health care providers (including primary care, specialist, and facilities) which receive specified payments with performance objectives and assume all health care and financial responsibilities for their patient populations.17 These concepts of a single accountable locus for comprehensive care suggest that occupational health, wellness, fitness for duty and work accommodation services will need to coordinate with or be integrated into these models. This change may be accelerated by the pursuit of employers for greater cost efficiency by having one provider for all health-related services. Occupational and environmental physicians will be challenged by the need to engage these new models of care in productive ways, including supporting these new systems of care with an appropriate level of occupational and environmental health competency.18

Middle and low income countries are also undergoing health systems transformations to improve health equity, cost efficiency and service delivery. Primary care is a key delivery system priority in these countries and is increasingly being viewed as the means for providing basic occupational health services which are generally unavailable to large proportions of working populations.19 Training for community health workers, medical technicians, nurses and general practitioners are major challenges for occupational and environmental medicine in these countries. New models of service delivery which extend the reach of available resources and creative uses of mobile and other low cost technologies for health are required to address these occupational and environmental medicine needs.

5 Retail and on-site clinics

Retail and on-site medical clinics are proliferating in the United States and are additional sources of care delivery system changes which will impact occupational and environmental medicine service models. Retail clinics located in pharmacies, large grocery stores and other retailers grew from approximately 250 in 2006 to over 1400 in 2013, and are projected to grow to 4000 by 2015.20 These clinics began as sources of simple, protocol driven non-urgent care such as vaccinations and upper respiratory infections, but are expanding to include wellness, care management and an array of primary care and other medical services for employers such as fitness for duty and periodic examinations. This trend is being fueled by employer needs to control health care costs and improve worker productivity.21

There are few comprehensive data on the number of on-site clinics, but one survey of 72 companies by World At Work reported that 25% of respondents representing more than a dozen industries had on-site clinics.22 In a separate larger survey of on-site clinics 66% offered occupational health services, 56% performed ergonomic assessments and 55% performed United States Occupational Safety and Health Administration required testing. 21 Occupational and environmental medicine services are only partially integrated into on-site clinics today but the potential exists for this to accelerate. Most on site clinics are third party vendor arrangements which offer flexibility to employers for scaling up or down without incurring costs of adding or reducing employees. These outsourced clinics have the potential for integration of routine health, safety and environmental services, which are often outsourced to environmental or site services companies.

6 Big data

Scale of data generation

The quantity, variety and speed of data generation today are unprecedented and growing at exponential rates. This is often referred to as “big data” because these exceed the capacity of existing information management systems to handle them. In 2010 it was estimated that the daily rate of global data generation was approximately 2.5 exabytes (2.518) of information and growing at 40% or more per year. For purposes of comparison, one exabyte is more than four thousand times the information stored in the Library of Congress.23 These data changes have been fueled by the pervasive instrumentation and interconnection of our world resulting from the enormous growth of networked sensors (fixed, mobile and aerial), mobile devices and unstructured data from text, social media, images, video, voice and multi-media. For example, the UN reported in 2011 that there were 86 mobile cellular phone subscriptions per 100 global inhabitants, 15.7 per 100 inhabitants with active cellular broad band subscriptions, and 34 per 100 households with home internet access.24 More than 30 million networked sensor nodes are now present in the transportation, automotive, industrial, utilities, and retail sectors and are increasing at a rate of more than 30 percent a year.23 Today, Twitter generates more than 7 tera bytes of data per day and FaceBook more than 10 tera bytes per day.25

Value from big data

The generation of massive quantities of diverse forms of data together with new technologies to aggregate, integrate and analyze these data is transforming every sector of society and will transform public health and occupational and environmental medicine. Value domains being exploited in industries include improving operational efficiency such as with radio frequency identification tracking of product movement for automated supply chain management. Other major areas for data and analytics enabled value creation include labor productivity, effectiveness of product and service marketing and delivery, and accelerating discovery and innovation. The rapid ingestion, transformation and integration of multi-source data are coupled to advanced analytics to pursue improved quality and reliability, lower unit cost, accelerate research and development, transform processes and create new business models. Use cases (practical applications of big data use to achieve specific user prioritized goals) are abundant in many industries such as: a) real time fraud detection in the banking and insurance industries using pattern recognition, b) modeling and simulation for risk management in enterprise functions from supply chain to facilities management optimization, and c) real time product performance monitoring for quality improvement using embedded sensor, geospatial, video and other data.

Health data

The health care delivery system and public health, including occupational and environmental medicine, are repositories of large quantities of heterogeneous data. For example, data in medical images, pathology specimens, surgical videos, telemetry, text in records, and social and web based exchanges are high density data sources in health care delivery. In public health large volumes of data are captured from vital statistics, surveys, biometric screening, biological, toxicological and environmental testing, inspections and numerous programs. In occupational and environmental medicine similar types of data are collected or used as well as fixed and mobile sensor data from equipment, effluents, accidents, medical monitoring and industrial hygiene and safety surveillance. Data challenges for occupational and environmental medicine related to the aggregation and analysis of integrated sets of occupational, medical and environmental data will be overcome as these technologies become available and affordable for practitioners and researchers.

The opportunity

Big data in health care and public health are capable of being accessed with new communication and information technologies that are better able to collect, curate, analyze and share them. This provides a transformative opportunity for generating information and creating knowledge with increased speed, collaboration and personalization. In public health, for example, surveillance intelligence, which is essential for prevention, protection and assessment of health, could be vastly improved in currency (e.g. real time), quality and speed of dissemination by rapid coupling of existing public health and medical data to: a) geospatial sensor data from mobile and aerial devices, b) observation, intent and sentiment data from social networking, and c) internet traffic patterns. The value of such real time insights from the aggregation of these varied and high frequency data flows has been demonstrated. For example, very strong correlations have been found between content-usage patterns with Twitter tweets and Google searches for infectious disease outbreaks and responses to natural disasters. 26 Open data initiatives such as those by state and federal are another good example. These freely accessible data repositories facilitate gathering and integrating multi-sectoral data from communities, and are extremely valuable for population health and environmental assessments or research, particularly with regards to social determinants of health and environmental exposures.

In the health care delivery system, multi-source data are increasingly being used for outcomes improvement. Approaches to therapeutics and care management are being redefined by combining large clinical data repositories with administrative data sets and sensor data to personalize care plans. New insights are being generated from these data using advanced quantitative methods such as patient similarity analytics which identifies cohorts of similar individuals based on large numbers of clinical and non-clinical feature vectors or indicators.27 For example, Optum Health (a United Health Care business) and the Mayo Clinic formed Optum Labs in 2013. This new collaborative enterprise provides infrastructure and tools for the health care industry, academic institutions and other organizations to aggregate information for large scale analytics to improve patient care, cost and quality.28

Some dependencies

Realizing the full potential of big data in health has many dependencies such as data skills requirements. For occupational and environmental medicine as for other disciplines, the need to develop professionals who understand data and have moderately advanced analytical skills will become acute. These skills are required for using such data for program design and evaluation, impact assessments, and new models for services delivery, operational efficiency and for research. There exist additional challenges to achieving broad based value from big data. Some examples include greater standardization of protocols for the transmission and sharing of data with different formats, compliance with existing and evolving privacy and security requirements, and the development of sustainable business models that fund freely accessible big data infrastructure.

From Worker Health To Citizen Health

Moving upstream

This commentary has explored a subset of major forces which are causing fundamental transformations in many societal sectors. The demographic shift to urban centers, the burden of noncommunicable diseases, challenges in rapid economic growth countries, changes in health care delivery systems and the rapid pace of data generation and use were selected because their effect on occupational and environmental medicine is likely to be significant and sustained. All are contributing to changes in the health status and productive capacity of people before they enter the workforce and as workers. All are also challenging the ability of worker-focused interventions to further advance prevention at all levels. Advancing the health of workers will increasing involve moving upstream of the workplace to involve multiple community sectors which together with the workplace nurture human resilience and vitality and contain the “real” causes of death and disability.29

How to move upstream

Moving upstream requires extending the systems approach which has been applied successfully inside the workplace to the broader ecosystem in which workers live and interact. Participation and leadership are needed in the development of strategies and interventions directed at shared pathways that impact social, environmental and physical conditions in communities. New analytic methods and use of new forms and varieties of data will be essential to identify with greater confidence and precision where the best opportunities exist for intervention and what the next best choice for action is at given points in time.

We need to create the same strong and effective partnerships with multi-sectoral leaders and communities that we have for safety and health at work with management, government, workers, unions and suppliers. Forging and sustaining these complicated partnerships, however, will be significantly more challenging. Unlike partnerships created in the pursuit of healthy workplaces and safe products, community public private partnerships involve relatively autonomous parties, the need for compromise in strategies and tactics, demanding leadership and governance requirements, and challenging liability, funding and other requirements. But these challenges can be overcome when motivated by shared significant hardship and when objectives are aligned, communication and accountability are clear and collaborative ways of working are established.30 Effective community public private partnerships have addressed various community wide needs ranging from infrastructure development to natural disasters, terrorism preparedness, infectious disease pandemics, and deaths from motor vehicle accidents.31, 32

Employers have been deeply engaged historically in community improvement and crisis preparedness and are now increasingly becoming active participants in community health and environmental improvement partnerships. An early example is the Mid-America Coalition on Health Care (MACHC) in the Kansas City/Missouri area.33 It began as an employer coalition focused on health care costs and outcomes of employees and their families, and has since expanded to include diverse health stakeholders and broader initiatives in depression, cardiovascular disease, nutrition, fitness and tobacco. Other partnerships have pursued a range of community health priorities ranging from water fluoridation and oral health to obesity, walkable communities, schools, chronic diseases and access to primary care and medical homes.34

Community partnerships

The role of social determinants in the health of populations including workers has been recognized for many years in the public health community,29, 35 but sustained and effective multi-sectoral partnerships for addressing these have been limited. However, the threat to national economies and economic development from health care cost, equity and access issues has garnered the attention of government and private sector leaders in an unprecedented fashion.36 Government and private sector leaders now recognize that noncommunicable diseases including cardiovascular, respiratory, cancer, diabetes and injuries are driving health care cost increases and disease burdens, are rooted in interactions among multiple sectors, and require community-based approaches for mitigating these impacts. Examples of such initiatives include the Million Hearts campaign sponsored by the US Department of Health and Human Services, the City of Philadelphia’s campaign to reduce smoking and childhood obesity, and the Ripple Foundation’s new ReThink Health initiative.

The Million Hearts Campaign (MHC) involves extensive public private partnerships to improve health care delivery system performance related to improved aspirin use, blood pressure control, cholesterol disorders control, and smoking reduction (“ABCS”).37 The campaign targets health care providers and outpatient health care facilities and uses reporting, measurements and communication to promote engagement and change. Health insurers, pharmacy chains and health care delivery systems are prominent employer partners in the campaign.

The “Get Healthy Philly” initiative of the City of Philadelphia is a multi-sectoral initiative designed to reduce smoking, increase physical activity, improve nutritious food consumption and reduce rates of childhood obesity. Extensive collaboration is occurring in this initiative between diverse community sectors including the business community, city government agencies, community groups, health care payers and providers, the school system and the media. Targets for improving the healthiness of the community in support of easy, healthy behaviors include: changes to the physical environment (walkability, bike ability, parks and recreation), school nutrition, retail food outlet stocks of fruits and vegetables, restaurant industry and food preparation and tobacco control policies.38

The Ripple Foundation’s mission is to bring innovation and systems thinking to major challenges in health and its main initiative is ReThink Health.39 ReThink Health supports multi-sectoral collaboration strengthening leadership and the use of evidence-based approaches to stewardship of community resources along with training and tools for using systems science and taking action. In 2011, it began the Healthy Columbia, South Carolina campaign in zip code 29203 to improve access to primary care, reduce emergency department visits and improve the health of the population. This region is characterized by high rates of uninsurance, hypertension, over weight and diabetes and high rates of emergency department visits. The initiative has recruited strong participation and leadership from health care providers, private sector insurers and employers, the City of Columbia, South Carolina, the South Carolina Health Department and Environmental Control, faith-based and other community organizations. Early priorities have included successfully recruiting and training leaders, engaging community members and initiating work to develop community-based wellness activities, health literacy interventions and planning for improving access to primary care.

Citizen health: a new paradigm

The view of worker health as an outcome of more than the workplace has roots in our specialty of occupational and environmental medicine as alluded to by Jean Spencer Felton MD, one of the most revered occupational medicine teachers and historians, when he wrote more than fifty years ago: “No patient-employee, when seen in the industrial dispensary or in the office of the consulting surgeon, can be viewed as the possessor of a single clinical entity unrelated to the life events which he experiences every day, day after day, in a continuum.”40 Social, environmental and physical interactions outside the work environment are key to the initial development of healthy behaviors and to long term health behavior change.29 This suggests a need for a new paradigm for advancing the health of working people from workplace and worker-focused to community and citizen-focused. (Figure 1) Citizen-centered health is a concept that has been used to frame the approach to healthy behavior that is dependent on changes to social and environmental enablers and inhibitors to “…bring about a way of life—at home, work, and school—that makes it easier for members of a community to adopt and maintain healthful practices.” 41

Workers as citizens challenge occupational and environmental professionals to extend further the boundaries and partnerships for better health of working populations by engaging communities. Achieving better health for greater productivity and lower health related cost is dependent on the creation of healthier community environments and not just excellence in workplace health, wellness and safety programs.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: None

Other Sources of Support: None

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None

End Notes

- 1.Spenser Felton J. 200 Years of occupational medicine in the U.S. J Occup Med. 1976;18 (12):809–817. doi: 10.1097/00043764-197612000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine. Integrating Employee Health: A model program for NASA. National Academy Press; 2005. [Accessed on April 17, 2013]. http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=11290. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. [accessed on April 20, 20–13];Preventing disease through healthy environments. towards an estimate of the environmental burden of disease. 2006 http://www.who.int/quantifying_ehimpacts/publications/preventingdisease.pdf.

- 4.World Bank. [accessed April 20, 2013];Country and lending groups. http://data.worldbank.org/about/country-classifications/countrand-lending-groups.

- 5.Bisson P, Kirkland R, Stephenson E. The Great rebalancing. McKinsey; Jun, 2010. [accessed April 20, 2013]. http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/globalization/the_great_rebalancing. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. [Accessed on April 20, 2013];World urbanization prospects. 2011 Revision. http://esa.un.org/unpd/wup/pdf/WUP2011_Highlights.pdf.

- 7.Heilig G. World urbanization prospects. Presentation at the center for strategic and International studies (CSIS); Washington, DC. 2012; 7 June ; 2011. [accessed on April 20, 2013]. Revision. http://esa.un.org/wpp/ppt/CSIS/WUP_2011_CSIS_4.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Economic Forum. Harvard School of Public Health. [accessed on April 20, 2013];The Global economic burden of non-communicable diseases. 2011 http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Harvard_HE_GlobalEconocBurdenNonCommunicableDiseases_2011.pdf.

- 9.World Health Organization. [accessed on April 20, 2013];Global status report on noncommunicable diseases. 2010 http://www.who.int/nmh/publications/ncd_report2010/en/

- 10.Nikolic IA, Stanciole AE, Zaydman M. Chronic emergency: why NCDs matter. World Bank; 2011. [accessed on April 20, 2013]. http://siteresources.worldbank.org/HEALTHNUTRITIONANDPOPULATION/Resources/281627-1095698140167/ChronicEmergencyWhyNCDsMatter.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keehan SP, Cuckler GA, Sisko AM, Madison AJ, Smith SD, Lizonitz JM, et al. National health expenditure projections: modest annual growth until coverage expands and economic growth accelerates. HealthAffairs. 2012;31(7):1–13. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control. Chronic diseases: the power to prevent, the call to control. Department of Health and Human Services; 2009. [accessed on April 20, 2013]. http://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/publications/aag/pdf/chronic.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goetzel RZ, Pei XF, Tabrizi MJ, Henke RM, Kowlessar N, Nelson CF, Metz RD. Ten modifiable health risk factors are linked to more than one-fifth of employer-employee health care spending. HealthAffairs. 2012;31(11):2474–2484. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goetzel RZ, Anderson DR, Whitmer RW, Ozminkowski RJ, Dunn RL, Wasserman J. The relationship between modifiable health risks and health care expenditures. an analysis of the multi-employer HERO health risk and cost database. J Occup Environ Med. 1998;40(10):843–54. doi: 10.1097/00043764-199810000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baicker K, Cutler D, Song Z. Workplace wellness programs can generate savings. Health Affairs. 2010;29;2:304–311. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robert Graham Center. American Academy Family Physicians. [accessed April 20, 2013];The patient-centered medical home. history, seven core features, evidence and transformational change. 2007 http://www.aafp.org/online/etc/medialib/aafp_org/documents/aout/pcmh.Par.0001.File.dat/PCMH.pdf.

- 17.Medicare Payment Advisory Committee. [accessed on April 20, 2013];Accountable care organizations. http://www.medpac.gov/chapters/Jun09_Ch02.pdf.

- 18.McLellan RK, Sherman B, Loeppke RR, McKenzie J, Mueller K, Yarborough CM, Grundy P, Allen H, Larson PW. Optimizing health care delivery by integrating workplaces, homes, and communities. J Occup and Environ Med. 2012;54 (4):504–512. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31824fe0aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hague Conference. World Health Organization. [accessed April 20, 2013];Scaling up access to essential interventions and basic services for occupational health through integrated primary health care. http://www.slideshare.net/who2012/the-hague-conferencebackground-document-2-13604291.

- 20.Merchant Medicine. [accessed April 20, 2013]; http://www.merchantmedicine.com/home.cfm.

- 21.Towers Watson. [accessed April 20, 2013];On-Site health center. survey report. 2012 http://www.towerswatson.com/en/Insights/IC-Types/SurveyResearch-Results/2012/07/Onsite-Health-Center-Survey-2012.

- 22.WorldAtWork. [accessed April 20, 2013];Quick survey. on-site clinics. 2011 http://www.worldatwork.org/waw/adimLink?id=49195.

- 23.McKinsey Global Institute. [accessed April 20, 2013];Big Data: the next frontier for innovation, competition, and productivity. 2011 http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/business_technology/big_data_the_next_frontier_for_innovation.

- 24.International telecommunications Union. [accessed on April 20, 2013];Measuring the information society. http://www.itu.int/dms_pub/itu-d/opb/ind/D-IND-ICTOI-2012SUM-PDF-E.pdf.

- 25.IBM. [accessed April 20, 2013];Understanding big data. http://www-01.ibm.com/software/data/infosphere/hadoop/

- 26.United Nations. Global Pulse. Big data for development: challenges and opportunities. http://www.unglobalpulse.org/sites/default/files/BigDataforDevelopment-UNGlobalPulseJune2012.pdf.

- 27.Sun J, Wang F, Hu J, Ebadollahi J. Supervised patient similarity measure of heterogeneous. [accessed July 26 2013];SIGKDD Explorations. 2012 14(1):16–24. http://www.kdd.org/sites/default/files/issues/V14-01-03-Sun.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 28. [accessed July 26 2013];Optum, Mayo Clinic Partner to Launch Optum Labs: An Open, Collaborative Research and Innovation Facility Focused on Better Care for Patients. http://www.unitedhealthgroup.com/newsroom/news.aspx?id=4fa05ad3-127a-432d-8dfb-6109f7accdaf.

- 29.McGuiness WH, Foege WH. Actual causes of death in the United States. JAMA. 1993;270(18):2207–2212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The National Association of State Chief Information Officers. [accessed July 26 2013];Key to collaboration: building effective public-private partnerships. http://www.nascio.org/publications/documents/nascio-keys%20to%20collaboration.pdf.

- 31.Federal Emergency Management Agency. Building resilience through public private partnerships. [accessed July 26 2013];Progress Report. 2012 http://www.fema.gov/txt/privatesector/ca_ppp.txt.

- 32.Centers for Disease Control. Ten great public health achievements -- United States, 1900–1999. MMWR. 1999 Apr 02;48(12):241–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.National Business Coalition on Health. National Leadership Council. Building healthy communities: should employers care? 2009 http://www.nbch.org/NBCH/files/ccLibraryFiles/Filename/000000000798/NHLC%20White%20Paper%20July%202009%20V2.pdf.

- 34.Webber A, Mercure S. Improving population health: the business community imperative. [accessed July 26 2013];Prev Chronic Dis. 2010 7(6):A121. http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2010/nov/10_0086.htm. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marmot MG, Bell R. Action on health disparities in the United States: commission on social determinants of health. JAMA. 2009;301(11):1169–71. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.World Economic Forum. McKinsey Institute. [accessed April 20, 2013];Sustainable health systems visions, strategies, critical uncertainties and scenarios. 2013 http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_SustainableHealthSystems_Report_2013.pdf.

- 37.Frieden TR, Berwick DM. The “Million Hearts” initiative preventing heart attacks and strokes. NEJM. 2011:e(27)1–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1110421. 10.1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.City of Philadelphia. [accessed April 20, 2013];GetHealthyPhilly. www.phila.gov/gethealthyphilly.

- 39.Ripple Foundation. [accessed July 30 2013];Columbia South Carolina. http://rippelfoundation.org/rethink-health/action/regions/columbia-south-carolina/

- 40.Spencer Felton J. Evaluation of the whole man. J Occup Med. 1961:579–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Woolf SH, Dekker MM, Rothenberg Byrne F, Miller WD. Citizen centered health promotion building collaborations to facilitate healthy living. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40(1S1):S38–S47. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]