Abstract

Background: Rift Valley fever (RVF) is a zoonosis of domestic ruminants in Africa. Blood-fed mosquitoes collected during the 2006–2007 RVF outbreak in Kenya were analyzed to determine the virus infection status and animal source of the blood meals.

Materials and Methods: Blood meals from individual mosquito abdomens were screened for viruses using Vero cells and RT-PCR. DNA was also extracted and the cytochrome c oxidase 1 (CO1) and cytochrome b (cytb) genes amplified by PCR. Purified amplicons were sequenced and queried in GenBank and Barcode of Life Database (BOLD) to identify the putative blood meal sources.

Results: The predominant species in Garissa were Aedes ochraceus, (n=561, 76%) and Ae. mcintoshi, (n=176, 24%), and Mansonia uniformis, (n=24, 72.7%) in Baringo. Ae. ochraceus fed on goats (37.6%), cattle (16.4%), donkeys (10.7%), sheep (5.9%), and humans (5.3%). Ae. mcintoshi fed on the same animals in almost equal proportions. RVFV was isolated from Ae. ochraceus that had fed on sheep (4), goats (3), human (1), cattle (1), and unidentified host (1), with infection and dissemination rates of 1.8% (10/561) and 50% (5/10), respectively, and 0.56% (1/176) and 100% (1/1) in Ae. mcintoshi. In Baringo, Ma. uniformis fed on sheep (38%), frogs (13%), duikers (8%), cattle (4%), goats (4%), and unidentified hosts (29%), with infection and dissemination rates of 25% (6/24) and 83.3% (5/6), respectively. Ndumu virus (NDUV) was also isolated from Ae. ochraceus with infection and dissemination rates of 2.3% (13/561) and 76.9% (10/13), and Ae. mcintoshi, 2.8% (5/176) and 80% (4/5), respectively. Ten of the infected Ae. ochraceus had fed on goats, sheep (1), and unidentified hosts (2), and Ae. mcintoshi on goats (3), camel (1), and donkey (1).

Conclusion: This study has demonstrated that RVFV and NDUV were concurrently circulating during the outbreak, and sheep and goats were the main amplifiers of these viruses respectively.

Key Words: : Rift Valley fever virus, Ndumu virus, Mosquito vectors, Aedes ochraceus, Mansonia uniformis, Blood meal identification, Host animals, Bunyavirididae, Alphavirus.

Introduction

Rift Valley fever (RVF) is a mosquito-borne zoonosis of domestic ruminants that causes epizootics/epidemics in Africa (Peters and Linthicum 1994). RVF is caused by the RVF virus (RVFV), (Bunyaviridae: Phlebovirus) (Torres-Velez and Brown 2004). Although first described by Daubney, Hudson, and Garnham during a 1930 outbreak in sheep, it is clear that periodic RVF epizootics were first observed in Kenya as early as 1912 among livestock in the Rift Valley province (Montgomery 1912, Stordy 1912–1913). The largest RVF outbreaks reported in Kenya occurred during the significant El Niño events of 1997/1998 and 2006/2007 in Garissa in the northeastern and Baringo regions in the Rift Valley (Woods et al. 2002, Nguku et al. 2010). RVFV is principally transmitted by floodwater mosquitoes of the subgenera Neomelaniconion and Aedimorphus, including Aedes mcintoshi, the most important vector in sub-Saharan Africa (Gargan et al. 1988).

RVFV has been isolated from many species of mosquitoes in Africa (Meegan and Bailey 1988, Fontenille et al. 1998). The 2006–2007 outbreak principally involved Ae. mcintoshi and Ae. ochraceus in Garissa, and Mansonia uniformis in Baringo (Sang et al. 2010). During this outbreak, seven other viruses, including Ndumu virus (NDUV), were isolated (Crabtree et al. 2009). NDUV (Togaviridae: Alphavirus) was first isolated in 1959 from Ma. uniformis (Kokernot et al. 1961), and recently from Ae. mcintoshi, Ae. ochraceus, Ae. tricholabis, and Culex rubinotus (Crabtree et al. 2009, Ochieng et al. 2013). Although NDUV antibodies have been identified in humans, the virus is not associated with human morbidity (Kokernot et al. 1961, Karabatsos 1985). However, some alphaviruses, including chikungunya, cause morbidity (Weaver et al. 2000, Sergon et al. 2007, 2008, Masembe et al. 2012) characterized by febrile illnesses, transient/debilitating arthritis, and encephalitis (Tesh 1982, Whitley 1990).

Despite the repeated isolation of RVFV from Ae. mcintoshi, Ae. ochraceus, and Ma. uniformis, the role of these species in the transmission of RVFV among humans and livestock remains unclear. Blood-feeding behavior of vectors is critical in the epidemiology of vector-borne pathogens (Kent 2009). Determination of the vertebrate host on which a vector feeds is important to understand for its role in amplification of pathogen(s) (Townzen et al. 2008). Previous studies have shown that Ae. mcintoshi (also known as Ae. lineatopennis) feeds preferentially on cows and humans (Linthicum et al. 1985a). However, vertebrate reservoirs of the virus and the diversity of hosts fed on by the principal vectors are poorly understood. RVFV was isolated from several mosquito species during the 2006–2007 outbreak without understanding which species were transmitting the virus.

Blood-fed mosquitoes collected during the outbreak were therefore identified, and their blood meals were analyzed using cytochrome c oxidase 1 (CO1) and cytochrome b (cytb) genes to determine the vectors and animals that were involved in transmission and amplification of RVFV, respectively. This information is important to the success of any vector control program that may be initiated. The genes occur in hundreds to thousands of copies per cell and contain independent 16.5-kb genomes; hence they are reliable and popular targets for identifying the source of arthropod blood meals (Alberts et al. 1994, Castro et al. 1998, Kent 2009) and can provide insights into the frequency and specificity of vector–host contact (Dick and Patterson 2007).

Materials and Methods

Study sites

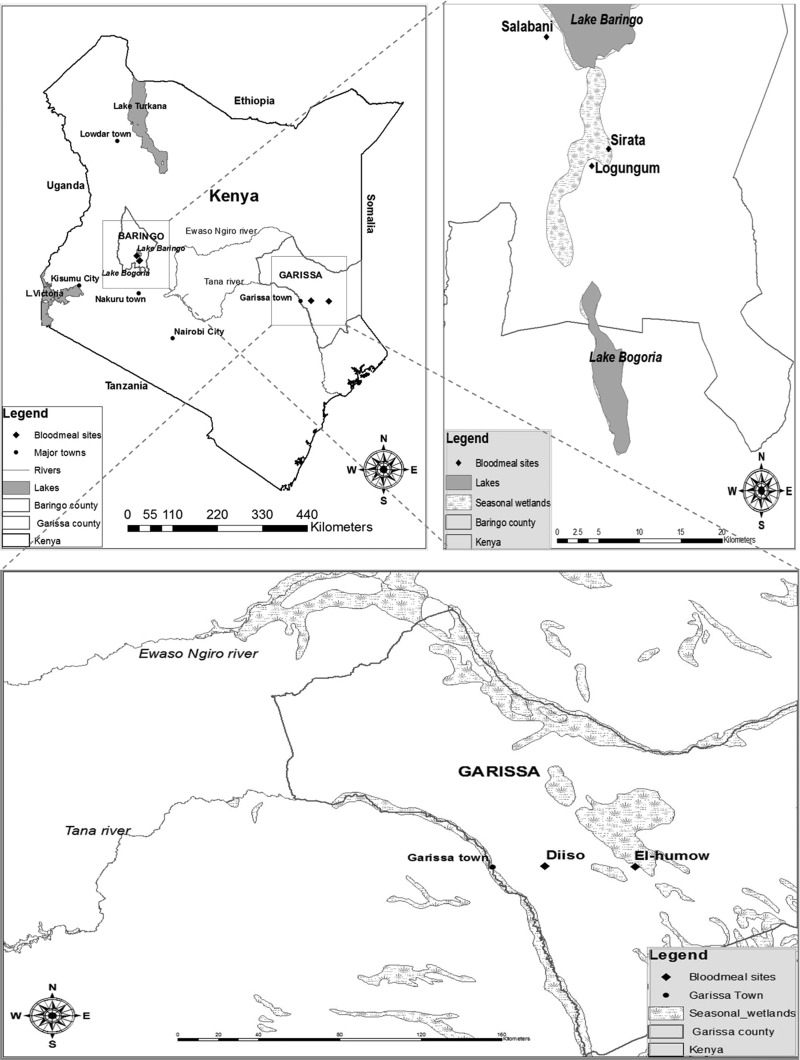

Mosquitoes were collected between December, 2006, and March, 2007, from Garissa (between −0.44901, 40.27096 and −0.44517, 39.87092) and Baringo (0.44405, 36.08008 and 0.45989, 36.09827) where RVF activity was detected in humans and/or livestock. Garissa borders the Tana River to the west and Somalia to the east and is an arid area with Somali Acacia and Commiphora bushlands and thickets. It experiences sporadic rainfall averaging 200–500 mm/year, with occasional torrential storms causing extensive flooding. The average temperatures range from 20°C to 38°C.

Baringo is a low-lying arid region, 250 km northwest of Nairobi, with northern Acacia and Commiphora bushlands and thickets. The annual rainfall averages 300–700 mm, and the daily temperature varies from 16°C to 42°C.

Mosquito collections and handling

Mosquitoes were collected using CO2-baited CDC light traps (John W. Hock, Gainesville, FL) from 1700 to 0600 h in villages where RVF cases were reported (Sang et al. 2010) and transferred to a field laboratory where they were immobilized using 99.5% triethylamine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Blood-fed mosquitoes were selected, identified to species using the keys of Edwards (1941) and Jupp (1986), and preserved individually in liquid nitrogen for transportation to the KEMRI laboratories in Nairobi for analyses.

Virus assay in blood-fed mosquitoes

Abdomens and heads of individual mosquitoes were separated from the thoraces using sterile forceps and dissecting pins and transferred into sterile 1.5-mL eppendorf tubes. The heads were preserved at −70°C for assay while awaiting cell culture and PCR results of virus testing of the abdomens. Blood meals were removed from the abdomens of individual mosquitoes by rupturing the abdominal cuticle using sterile 200-μL pipette tips and suspended in 300 μL of 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Fifty microliters of each suspension was inoculated onto confluent monolayers of Vero cells in 24-well plates grown in minimum essential medium (MEM) (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Sigma-Aldrich), 2% l-glutamine, and 2% antibiotic/antimycotic solution (100×) (Sigma-Aldrich). Infected cultures were incubated for 45 min to allow virus adsorption, after which 1 mL of MEM supplemented with 2% FBS, 2% l-glutamine, and 2% antibiotic/antimycotic solution (100×) (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to each well. The cultures were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 and monitored daily for cytopathic effects (CPE). Cultures showing 50–75% CPE were harvested for virus confirmation by RT-PCR.

Heads of virus positive abdomens were homogenized individually in 1.5-mL tubes containing 500 μL of homogenizing media comprised of MEM, supplemented with 15% FBS, 2% l-glutamine, and 2% antibiotic/antimycotic solution (100×) and assayed for virus infection as described for the blood meals.

Virus identification by RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from the supernatant of each positive culture by the TRIzol®-LS-Chloroform method (Chomczynski and Sacchi 1987). Extracted RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using SuperScript®III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) using random hexamers, followed by RT-PCR using AmpliTag Gold® PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) with primers targeting RVFV (Table 1). Thermocycling conditions included initial denaturation at 94°C for 3 min and 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 68°C for 45 s. The final cycle was completed with 7 min of extension at 72°C. Amplification products were resolved in 1.5% agarose gel in Tris-borate EDTA buffer stained with ethidium bromide.

Table 1.

DNA Sequences of the Primers Used, Their Target Genes/Proteins and Positions

| Virus | Gene target | Primer sequence | Position | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | RVFV | Glycoprotein M gene | RVF1 (5′-GAC TAC CAG TCA GCT CAT TAC C-3′) | 777–798 | Ibrahim et al. 1997 |

| RVF2 (5′-TGT GAA CAA TAG GCA TTG G-3′) | 1309–1327 | ||||

| 2. | Bunyavirus | Nucleocapsid protein | BCS82C (5′-ATG ACT GAG TTG GAG TTT CAT GAT GTC GC-3′) | 86–114 | Kuno et al. 1996 |

| BCS332V (5′-TGT TCC TGT TGC CAG GAA AAT-3′) | 309–329 | ||||

| 3. | Alphavirus | NSP4 | VIR 2052F (5′-TGG CGC TAT GAT GAA ATC TGG AAT GTT-3′) | 6971–6997 | Eshoo et al. 2007 |

| VIR 2052R (5′-TAC GAT GTT GTC GTC GCC GAT GAA-3′) | 7086–7109 | ||||

| 4. | Ndumu | Envelope (E1) gene | ND 124F (5′-CAC CCT AAA AGT GAC GTT-3′) | 124–141 | Bryant et al. 2005 |

| ND 632R (5′- ATT GCA GAT GGG ATA CCG-3′) | 615–632 |

RVFV, Rift Valley fever virus.

The isolates that did not amplify with RVFV primers were analyzed using alphavirus primers and further tested with primers that target conserved genes in the specific NDUV (Table 1).

Molecular identification of vertebrate source of blood meal

Genomic DNA was extracted from blood meals by QIAGEN DNeasy Blood and tissue kit (GmbH, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer's instructions. Extracted DNA was used as the template in subsequent COI PCR analyses targeting a 750-bp region using primer sequences VF1d_t1 (5′-TGTAAAACGACGGCCAGTTCTCAACCAACCACAARGAYATYGG-3′) and VR1d_dt (5′-CAGGAAACAGCTATGACTAGACTTCTGGGTGGCCRAARAAYCA-3′) (Ivanova et al. 2007). PCR cycling conditions included: 98°C for 1 min, 40 cycles of 98°C for 10 s, 57°C for 30 s, 72°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 7 min. The products were resolved in 1.5% agarose gel in Tris-borate EDTA buffer stained with ethidium bromide.

If the COI_ primer pair did not amplify the blood meal DNA, the samples were analyzed for cytb using primers L14841, forward (5′-CCATCCAACATCTCAGCATGATGAAA-3′) and H151494, reverse (5′-GCCCCTCAGAATGATATTTGTCCTCA-3′), which flank a 358-bp sequence (Kocher et al. 1989). The PCR was run using a thermocycling profile of one cycle of 1 min at 98°C, 40 cycles of 98°C for 30 s; 61°C for 20 s; 72°C for 30 s; and 72°C for 7 min. The products were resolved in 1.5% agarose gel in Tris-borate EDTA buffer stained with ethidium bromide.

DNA fragments were excised from gels and purified using GeneJET™ Gel Extraction Kit (Fermentas) following the manufacturer's instructions. Purified amplicons were sequenced using each primer pair in both directions (Macrogen Inc. South Korea), and the sequences were edited in MEGA software (Kumar et al. 2004). Edited sequences were used to query the GenBank DNA sequence database at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI; www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) using BLAST (Altschul et al. 1990) and BOLD (www.barcodinglife.org) with the default identification engine (Ratnasingham and Hebert 2007). For GenBank, an e-value of <1.0e-1671.0e-167 was used to determine a positive identification of a blood meal, and a 96–100% identity of vertebrate host used for BOLD (Sarkar and Trizna 2011).

Results

A total of 771 blood-fed mosquitoes were analyzed from Garissa (738) and Baringo (33). Ae. ochraceus and Ae. mcintoshi comprised 76% and 23.8%, respectively, of the total collection from Garissa, whereas all the Mansonia species were from Baringo. Ae. ochraceus blood meals were from goats (37.6%), cattle (16.4%), donkeys (10.7%), sheep (5.9%), humans (5.3%), and camels (2.7%) with 20.9% unidentified. Ae. mcintoshi fed on similar animals, including goats (35.2%), cattle (15.3%), donkeys (12.5%), sheep (6.3%), humans (5.1%), and 23.3% unidentified (Table 2).

Table 2.

Proportion of Blood Meals Taken from Different Vertebrate Hosts by Different Species of Mosquitoes in Garissa and Baringo

| Number (%) of mosquitoes feeding on vertebrate hosts | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area | Mosquito sp. | No. tested | Human | Cattle | Sheep | Goat | Donkey | Camel | Lesser Kudu | Duiker | Gazelle | Bird | Rat | Frog | Unidentified |

| Garissa | Ae. ochraceus | 561 | 30 (5.3) | 92 (16.4) | 33 (5.9) | 211 (37.6) | 60 (10.7) | 15 (2.7) | 1 (0.18) | 0 | 1 (0.18) | 1 (0.18) | 0 | 0 | 117 (20.9) |

| Ae. mcintoshi | 176 | 9 (5.1) | 27 (15.3) | 11 (6.3) | 62 (35.2) | 22 (12.5) | 3 (1.7) | 0 | 1 (0.6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 41 (23.3) | |

| Ae. sudanensis | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (100) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 738 | 39 (5.3) | 119 (16.1) | 45 (6.1) | 273 (37) | 82 (11.1) | 18 (2.4) | 1 (0.14) | 1 (0.14) | 1 (0.14) | 1 (0.14) | 0 | 0 | 158 (21.4) | |

| Baringo | Ma. uniformis | 24 | 0 | 1 (4) | 9 (38) | 1 (4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (8) | 0 | 0 | 1 (4) | 3 (13) | 7 (29) |

| Ma. africana | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 (100) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Hodgesia sp. | 7 | 1 (14) | 1 (14) | 1 (14) | 1 (14) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (14) | 1 (14) | 1 (14) | |

| Total | 33 | 1 (3) | 2 (6) | 12 (36) | 2 (6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (6) | 0 | 0 | 2 (6) | 4 (12) | 8 (24) | |

In Baringo, the Ma. uniformis had fed on sheep (38%), frogs (13%), duikers (8%), cattle (4%), goats (4%), and rats (4%) and unidentified (29%) (Table 2). In Garissa, RVFV-positive Ae. ochraceus had fed on human (1), cattle (1), sheep (4), goats (3), and an unidentified host (1). Disseminated RVFV infections, as indicated by presence of virus in the insect heads, were observed in mosquitoes with blood meals from sheep (3), a goat, and one unidentified host. A single RVFV disseminated infection was detected in Ae. mcintoshi, which had fed on a donkey. NDUV was isolated from Ae. ochraceus (13), Ae. mcintoshi (5), and Ae. sudanensis (1) with dissemination rates of 31%, 80%, and 0%, respectively. Ten of the Ae. ochraceus mosquitoes infected with NDUV had fed on goats, whereas infected Ae. mcintoshi, which also had disseminated infection in the heads, had fed on goats (2), a camel, and a donkey (Table 3).

Table 3.

RVFV and NDUV Infections in Mosquitoes Collected from Garissa and Baringo, Kenya

| RVFV | NDUV | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area | Species | No. | Vertebrate host | No. of blood meals | RVFV +ve blood meals | Infection rate (%) | RVFV +ve heads | Dissemination rate (%) | NDUV +ve blood meals | Infection rate (%) | NDUV +ve heads | Dissemination rate (%) |

| Garissa | Ae. ochraceus | 561 | Human | 30 | 1 | 3.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cattle | 92 | 1 | 1.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Sheep | 33 | 4 | 12.1 | 3 | 75 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Goat | 211 | 3 | 1.4 | 1 | 33.3 | 10 | 5 | 3 | 33 | |||

| Unidentified | 117 | 1 | 0.9 | 1 | 100 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 50 | |||

| Othersa | 78 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Ae. mcintoshi | 176 | Donkey | 22 | 1 | 4.5 | 1 | 100 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 100 | |

| Goat | 62 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 67 | |||

| Camel | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 33 | 1 | 100 | |||

| Othersb | 89 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Ae. sudanensis | 1 | Sheep | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 738 | 738 | 11 | 1.5 | 6 | 54.5 | 19 | 2.6 | 8 | 42 | ||

| Baringo | Ma. uniformis | 24 | Sheep | 9 | 4 | 44.4 | 4 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Goat | 1 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Unidentified | 7 | 1 | 14.3 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Othersc | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Ma. africana | 2 | Sheep | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Hodgesia sp. | 7 | Sheep | 1 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Othersc | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Total | 33 | 33 | 7 | 21.2 | 5 | 71.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

Other vertebrate hosts fed on by Ae. ochraceus from which no virus was isolated.

Forty-eight identified and 41 unidentified blood meals from which no virus was isolated.

Other vertebrate hosts fed on by the respective mosquito species from which no virus was isolated.

RVFV, Rift Valeey fever virus; NDUV, Ndumu virus; +ve, positive.

In Baringo RVFV-positive Ma. uniformis had fed on sheep (4), a goat, and an unidentified host. The overall RVFV dissemination rate was 83% (5/6). One Hodgesia sp. which fed on sheep had nondisseminated infection (Table 3).

Discussion

Most of the blood-fed mosquitoes from Garissa were Ae. ochraceus 561(76%) and Ae. mcintoshi 176 (23.8%). However, unengorged mosquitoes collected during the outbreak comprised Ae. mcintoshi (21.7%) and Ae. ochraceus (15.4%), among other species (Sang et al. 2010). Assuming that blood-fed Ae. ochraceus and Ae. mcintoshi are equally attracted to the CDC light traps, these results may suggest that blood-fed Ae. ochraceus survived longer compared to Ae. mcintoshi, a factor that may influence their vectorial capacity for RVFV and NDUV. Other factors affecting these percentages include proximity of the mosquitoes to traps and preferred host availability. Despite these differences, both species obtained blood meals from the same hosts in almost equal proportions, with goats, cattle, and donkeys the common source. This contrasts with previous observations that Ae. mcintoshi preferentially feeds on cattle (Anderson 1967, Metselaar et al. 1973, Linthicum et al. 1985a, Beier et al. 1990). Although this might suggest that the host-seeking pattern of mosquitoes is dynamic and is influenced by the composition and proportion of animal species present, the observed difference between this and earlier studies can also be attributed to improved methods of blood meal source identification.

In Garissa the percentage of Ae. ochraceus and Ae. mcintoshi with human blood was nearly identical (∼5%), which is quite significant considering the low human population in the area. Although it may appear that both species preferentially feed on goats (Capra hircus) over humans, goats are more common, located outdoors, and always susceptible to nocturnal-feeding mosquitoes (Beier et al. 1990). Among domestic animals, camels (Camelus dromedarius), whose population was low 102,314 (5.4%) compared to cattle 548,980 (28.9%), goats 753,759 (39.7%), and sheep 492,262 (25.9%) (Murithi et al. 2007), were the least fed upon. Antibodies to RVFV have been detected in camels in Kenya prior to and after the 2006–2007 outbreak (Britch et al. 2013).

There were few instances of mosquitoes feeding on wildlife, such as lesser kudu (Tragelaphus imberbis), gazelle (Gazella sp.), birds, and duiker (Cephalophus harveyi). This was either because of the generally low density of wildlife compared to livestock or the low preference for wildlife. Collection methods were also biased against mosquitoes that fed on wildlife because the traps were positioned proximally to human habitation and usually avoided by wildlife. There is no current data on wildlife census in this area, thus it is difficult to estimate their proportions relative to livestock. While our results may suggest that wildlife could be of limited significance in the epidemiology of RVFV during outbreaks, other studies have shown that the African buffalo (Syncerus caffer) and a number of other species have shown evidence of exposure to RVFV on the basis of the presence of antibodies (Davies and Martin 2003, Evans et al. 2008, Britch et al. 2013).

The rarity of Ae. sudanensis, represented by 1/738 blood-fed and 1,727/164,626 of unfed specimens (Sang et al. 2010), suggests that this species may be less important regarding RVFV transmission. The significance of 23% of the blood meals originating from unidentified hosts is unknown.

In Baringo, the number of engorged specimens was small, with Ma. uniformis being the most common (72.7%) and Ma. africana (6%) present. Both species readily fed on sheep, despite the presence of both sheep and goats in large numbers, but Ma. uniformis also fed on cattle, goat, duiker, rat, frog, and a relatively high number of unidentified species. The frog feeding by Ma. uniformis is not surprising because they occur in swampy habitats together. The seven Hodgesia species tested each fed on a different animal.

FIG. 1.

Map of Kenya showing the two regions, Baringo and Garissa, where the blood-fed mosquitoes were collected during the 2006–2007 Rift Valley fever outbreak.

Ae. ochraceus and Ae. mcintoshi were exclusive to Garissa and Ma. uniformis to Baringo, suggesting that both areas, separated by 400 km, have distinct mosquito species that drive RVF epizootics/epidemics. In northeastern Kenya, there are abundant temporarily flooded habitats (dambos), which are the preferred aestivation and breeding sites for floodwater mosquitoes (Linthicum et al. 1983, 1984) and are thought to be the source of virus-infected mosquitoes (Linthicum 1985b). The presence of abundant open swampy areas along the shores of lakes Baringo and Bogoria are the likely reason for the predominance of Mansonia species in Baringo (Lutomiah et al. 2013) as they are perfect immature development sites for these mosquitoes (Wharton 1962).

Infection and dissemination rates of RVFV were 1.8% (10/561) and 50% (5/10), respectively, in Ae. ochraceus and 0.56% (1/176) and 100% (1/1) in Ae. mcintoshi. Vectorial competence studies of Ae. mcintoshi have shown the species to be highly inefficient due to a salivary gland barrier (SGB) (Turell et al. 2008), but little is known about Ae. ochraceus except that RVFV was first isolated from it in Senegal (Fontenille et al. 1998). However, detection of disseminated infection in the heads of this species suggests that Ae. ochraceus have the potential to transmit RVFV unless they have a SGB and that they may play a major role during epizootics/epidemics. Both infection and dissemination rates in Ae. ochraceus were highest in specimens that had fed on sheep, 12.1% and 75%, followed by goats, 27.2% and 33%, respectively. This suggests that Ae. ochraceus, and Ma. uniformis with 44.4% and 100% infection and dissemination rates, respectively, were involved in the transmission of RVFV to these animals during the outbreak. However, given the low number of specimens from Baringo, it is difficult to ascertain which animals were mostly associated with Mansonia species, and RVFV amplification. The nondisseminated infection in Ma. uniformis and Hodgesia sp. that fed on goat and sheep, respectively, may have been due to a midgut escape barrier or these mosquitoes had a recent infection. The role of Hodgesia sp. in RVFV amplification and transmission remains unclear as it has not been previously incriminated. The only mosquito with a blood meal from a donkey in our study had a disseminated RVFV infection; however, equines are generally resistant to RVFV infection (Daubney 1931, Imam 1979), and there is no evidence that donkeys develop viremias after exposure.

Although our findings may suggest that Ae. ochraceus was the species most involved in RVFV transmission in Garissa, the number of RVFV isolates and infection rates were comparable between unengorged Ae. mcintoshi (26; 0.07%) and Ae. ochraceus (23; 0.09%) (Sang et al. 2010). In Baringo, Ma. uniformis was the significant species in RVFV amplification and transmission, yielding 15 isolates; and an infection rate of 0.03% against two isolates and 0.01%, respectively, for Ma. africana in unengorged specimens (Sang et al. 2010). These rates are based on the assumption that in every positive pool only one mosquito is infected.

An interesting observation was the lack of blood-fed Culex sp. mosquitoes sampled, yet 15% (n=24,633) of the unengorged mosquitoes were Culex mosquitoes (Sang et al. 2010). This may suggest that when engorged, these mosquitoes are probably less attracted to CO2. Various Culex spp. are important in RVFV transmission in other parts of Africa (Linthicum et al. 1985b) and are highly efficient vectors in experimental studies (Turell et al. 2008).

The isolation of NDUV supports evidence that other viruses were circulating alongside RVFV (Crabtree et al. 2009). NDUV infection rates in Ae. mcintoshi (2.8%) and Ae. ochraceus (2.5%) were comparable. NDUV was first isolated from Ma. uniformis (Kokernot et al. 1961), and recently from Ae. mcintoshi, Ae. ochraceus, Ae. tricholabis, and Cx. rubinotus (Crabtree et al. 2009, Ochieng et al. 2013). Given that Cx. rubinotus preferentially feeds on rodents (Jupp et al. 1976), which are susceptible to NDUV (Kokernot et al. 1961), it is possible that rodents play a role in its circulation. Lack of recovery of NDUV from Baringo, where the virus is circulating (Ochieng et al. 2013) and Cx. rubinotus and Ma. uniformis are widely distributed (Lutomiah et al. 2013), may have been due to the small number of specimens sampled.

Although there was only one RVFV isolate from blood meals from goats, 13/19 (68.4%) of NDUV isolates were from mosquitoes with blood meals from goats, of which 5/13 had disseminated infection, indicating that 8/13 blood meals may have been from infected goats. This suggests that goats are susceptible to and significant in the maintenance and amplification of NDUV. However, it is also possible that some of the engorged mosquitoes with nondisseminated infection were already infected with RVFV or NDUV from a previous host at the time of ingesting the blood meals that were identified. This suggests that the virus in the identified blood meal may have been due to a “contamination” from the mosquito tissues to the blood meal during processing to suspend in PBS.

Another interesting observation was that no mixed infection was detected despite both viruses being isolated from same vectors. This may be a case of virus interference in nature, a phenomenon whose significance is unknown, but probably reduces the overall impact of an outbreak through “competition” between different viruses for the same vectors and amplifying hosts. Several other viruses were also circulating in the study areas during the outbreak (Crabtree et al. 2009). The low infection rates observed for most of them, coupled with the small numbers of engorged mosquitoes tested in this study, may also explain the lack of mixed infection.

No virus was isolated from blood meals from wildlife, probably due to the low numbers collected and their inability to develop viremias sufficient to infect mosquitoes. For instance, antelopes develop low prevalence of antibodies to RVFV (Davies 1975), although recent work by Britch et al. (2013) suggests that seroprevalence increases after outbreaks. Birds are refractory to RVFV, whereas susceptibility of deer species remains unknown (Fischer et al. 2013) and natural infection of rodents has been documented (Imam et al. 1979).

Conclusion

This study has shown that goats provided the highest number of blood meals to the mosquito vectors in Garissa during the outbreak, whereas most blood meals in Baringo came from sheep. Our results also support the findings reported by Sang et al. (2010) that Ae. ochraceus and Ma. uniformis may have been involved in RVFV transmission in Garissa and Baringo, respectively. They also confirmed concurrent circulation of RVFV and NDUV during the epizootic in Garissa and suggest that sheep were most likely responsible for amplifying RVFV in both regions, whereas goats were most involved in the amplification of NDUV in Garissa.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dunston Beti, John Gachoya and Reuben Lugalia, all of KEMRI, for their technical assistance in mosquito identification. This work received financial support from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist. This article is published with permission from the Director, Kenya Medical Research Institute.

References

- Alberts B, Bray D, Lewis J, Raff M, et al. Molecular Biology of the Cell, 3rd ed. New York: Garland Publishing Inc., 1994 [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Gish M, Miller W, Myers EW, et al. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol 1990; 215:403–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson D. Ecological studies on Sindbis and West Nile viruses in South Africa. III. Host preferences of mosquitoes as determined by the precipitin test. S Afr J Med Sci 1967; 32:31–39 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beier JC, Odago OW, Onyango FK, Asiago CM, et al. Relative abundance and blood feeding behavior of nocturnally active culicine mosquitoes in western Kenya. JAMCA 1990; 6:207–212 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britch SC, Binepal YS, Ruder MG, Kariithi HM, et al. Rift Valley fever risk map model and seroprevalence in selected wild ungulates and camels from Kenya. PLoS 2013; 8:e66626. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant JE, Crabtree MB, Nam VS, Yen NT, et al. Isolation of arboviruses from mosquitoes collected in northern Vietnam. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2005; 73:470–473 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro JA, Picornell A, Ramon M. Mitochondrial DNA: A tool for population genetics studies. Int Microbiol 1998; 1:327–332 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem 1987; 162:156–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree M, Sang R, Lutomiah J, Richardson J, et al. Arbovirus surveillance of mosquitoes collected at sites of active Rift Valley fever virus transmission: Kenya, 2006–2007. J Med Entomol 2009; 46:961–964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daubney R, Hudson JR, Garnham PC. Enzootic hepatitis or Rift Valley fever. An undescribed virus disease of sheep, cattle and man from East Africa. J Pathol Bacteriol 1931; 34:545–579 [Google Scholar]

- Davies FG. Observations on the epidemiology of Rift Valley fever in Kenya. J Hyg 1975; 75:219–230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies FG, Martin V. Recognizing Rift Valley fever. FAO Animal Health Manual No. 17. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations 2003;1–45 [Google Scholar]

- Dick CW, Patterson BD. Against all odds: Explaining high host specificity in dispersal-prone parasites. Int J Parasitol 2007; 37:871–876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards FW. Mosquitoes of the Ethiopian Region. III. Culicine Adults and Pupae. London: British Museum (Natural History), 1941 [Google Scholar]

- Eshoo MW, Whitehouse CA, Zoll ST, Massire C, et al. Direct broad-range detection of alphaviruses in mosquito extracts. Virology 2007; 368:286–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans A, Gakuya F, Paweska JT, Rostal M, et al. Prevalence of antibodies against Rift Valley fever virus in Kenyan wildlife. Epidemiol Infect 2008; 136:1261–1269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer AJE, Boender G, Nodelijk G, de Koeijer AA, et al. The transmission potential of Rift Valley fever virus among livestock in the Netherlands: A modelling study. Vet Res 2013; 44:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontenille D, Traore-Lamizana M, Diallo M, Thonnon J, et al. New vectors of Rift Valley fever in West Africa. Emerg Infect Dis 1998; 4:289–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gargan TP, II, Clark GC, Dohm DJ, Turell MJ, et al. Vector potential of selected North American mosquito species for Rift Valley fever virus. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1988; 38:440–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim MS, Turell MJ, Knauert FK, Lofts RS: Detection of Rift Valley fever virus in mosquitoes by RT-PCR. Mol Cell Probes 1997; 11:49–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imam IZ, El Karamany R, Darwish MA. An epidemic of Rift Valley fever in Egypt. 2. Isolation of the virus from animals. Bull World Health Organ 1979; 57:441–443 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova VN, Zemlak ST, Hanner HR, Hebert DNP. Universal primer cocktails for fish DNA barcoding. Mol Ecol Notes 2007; 7:544–548 [Google Scholar]

- Jupp PG. Mosquitoes of Southern Africa. South Africa: Ecogilde, 1986:156 [Google Scholar]

- Jupp PG, McIntosh BM, Anderson D. Culex (Eumelanomyia) rubinotus Theobald as vector of Banzi, Germiston and Witwatersrand viruses. IV. Observations on the biology of C. rubinotus. J Med Entomol 1976; 12:647–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karabatsos N, ed. International Catalogue of Arboviruses Including Certain Other Viruses of Vertebrates, 3rd ed. San Antonio: American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene for the Subcommittee on Information Exchange of the American Committee on Arthropod-borne Viruses, 1985 [Google Scholar]

- Kent RJ. Molecular methods for arthropod bloodmeal identification and applications to ecological and vector-borne disease studies. Mol Ecol Resour 2009; 9:4–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocher TD, Thomas WK, Meyer A, Edwards VS, et al. Dynamics of mitochondrial DNA evolution in animals: Amplification and sequencing with conserved primers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 1989; 86:6196–6200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokernot RH, McIntosh BM, Worth CB. Ndumu virus, a hitherto unknown agent, isolated from culicine mosouitoes collected in northern Natal. Union of South Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1961; 10:383–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Tamura K, Nei M. MEGA3: Integrated software for Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis and sequence alignment. Brief Bioinform 2004; 5:150–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuno G, Mitchell CJ, Chang GJJ, Smith GC. Detecting bunyaviruses of the Bunyamwera and California serogroups by a PCR technique. J Clin Microbiol 1996; 34:1184–1188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linthicum KJ, Davies GF, Bailey CL, Kairo A. Mosquito species succession in a dambo in an East African forest. Mosq News 1983; 43:464–470 [Google Scholar]

- Linthicum KL, Davies FG, Bailey CL, Kairo A. Mosquito species encountered in a flooded grassland dambo in Kenya. Mosq News 1984; 44:228–232 [Google Scholar]

- Linthicum KJ, Kaburia HFA, Davies FG, Lindovist KJ. A blood meal analysis of engorged mosquitoes found in Rift Valley fever epizootic areas in Kenya. J Am Mosq Control Assoc 1985a; 1:93–95 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linthicum KJ, Davies FG, Kairo A, Bailey CL. Rift Valley fever virus (family Buyaviridae, genus Phlebovirus). Isolations from dipteral collected during an interepizootic period in Kenya. J Hyg 1985b; 95:197–209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutomiah J, Bast J, Clark J, Richardson J, et al. Abundance, diversity, and distribution of mosquito vectors in selected ecological regions of Kenya: Public health implications. J Vector Ecol 2013; 38:134–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masembe C, Michuki G, Onyango M, Rumberia C, et al. Viral metagenomics demonstrates that domestic pigs are a potential reservoir for Ndumu virus. Virol J 2012; 24:218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meegan JM, Bailey LC. Rift Valley fever, In Monath TP, ed. The Arboviruses: Epidemiology and Ecology, vol. IV Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press Inc., 1988:61–76 [Google Scholar]

- Metselaar D, van Someren ECC, Ouma JH, Koskei HK, et al. Some observations on Aedes (Aedimorphus) dentatus (Theo.) (Dipt. Culicidae) in Kenya. Bull Ent Res 1973; 62:597–603 [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery ER. Nairobi sheep disease. Annual Report of the Veterinary Pathologist for the year 1910–1911. 1912:37 [Google Scholar]

- Murithi MF, Mulinge MW, Wandera OE, Maingi MP, et al. Livestock Survey in the Arid Land Districts of Kenya. For Arid Lands Resource Management Project, (ALRMP-II). Nairobi, Kenya: Office of the President, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- Nguku PM, Shariff KS, Mutonga D, Amwayi S, et al. An Investigation of a major outbreak of Rift Valley fever in Kenya: 2006–2007. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2010; 5:5–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochieng C, Lutomiah J, Makio A, Koka H, et al. Mosquito-borne arbovirus surveillance at selected sites in diverse ecological zones of Kenya; 2007–2012. Virology 2013; 10:140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters CJ, Linthicum KJ. Rift Valley fever. In: Beran GW, ed. Handbook of Zoonoses. Section B: Viral, 2nd ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, Inc., 1994:125–138 [Google Scholar]

- Ratnasingham S, Hebert NDP. BOLD: The Barcode of Life Data System (http://www.barcodinglife.org). Mol Ecol Notes 2007; 7:355–364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sang R, Kioko E, Lutomiah J, Warigia M, et al. Rift Valley fever virus epidemic in Kenya, 2006/2007: The Entomologic Investigations. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2010; 83:28–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar IN, Trizna M. The Barcode of Life Data Portal: Bringing the biodiversity informatics divide for DNA barcoding. PloS One 2011; 6:e14689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sergon K, Yahaya AA, Brown J, Bedja SA, et al. Seroprevalence of chikungunya virus infection on Grande Comore Island, Union of the Comoros, 2005. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2007; 76:1189–1193 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sergon K, Njuguna C, Kalani R, Ofula V, et al. Seroprevalence of chikungunya virus (CHIKV) infection on Lamu Island, Kenya, October 2004. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2008; 78:333–337 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stordy RJ. Mortality among lambs. British East Africa: Annual Report Department of Agriculture, 1912–1913:35 [Google Scholar]

- Tesh RB. Arthritides caused by mosquito-borne viruses. Ann Rev Med 1982; 33:31–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Vélez F, Brown C. Emerging infections in animals-potential new zoonoses? Clin Lab Med 2004; 24:825–838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townzen JS, Brower A VZ, Judd DD. Identification of mosquito bloodmeals using mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase subunit I and cytochrome b gene sequences. Med Vet Entomol 2008; 22:386–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turell JM, Linthicum KJ, Patrican AL, Davies FG, et al. Vector competence of selected African mosquito (Diptera:Culicidae) species for Rift Valley Fever Virus. J Med Entomol 2008; 45:102–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver SC, Dalgarno L, Frey TK, Huang HV, et al. Family Togaviridae. In Regenmortel CMF, et al., eds. Virus Taxonomy. Classification and Nomenclature of Viruses. Seventh Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. San Diego, CA; Academic Press, Inc., 2000:879–889 [Google Scholar]

- Wharton RH. The biology of Mansonia mosquitoes in relation to the transmission of filariasis in Malaya. Bull Inst Med Res (Malaysia) 1962; 11:114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitley RJ. Viral encephalitis. N Engl J Med 1990; 3:242–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods CW, Karpati MA, Grein T, McCarthy N, et al. An outbreak of Rift Valley fever in northeastern Kenya, 1997–98. Emerg Infect Dis 2002; 8:138–144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]