Abstract

Background

Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging evaluation of the painful failed shoulder arthroplasty is a useful imaging modality due to advancements in metal artifact reduction techniques, which allow assessment of the integrity of the supporting soft-tissue envelope and the implant.

Questions/Purposes

The focus of this pictorial review is to illustrate the benefits of MR imaging, whether used alone or as an adjunct to other imaging modalities, in aiding the clinician in the complex decision making process.

Methods

A PubMed (MEDLINE) search focusing on the complications and imaging assessment of shoulder arthroplasty was performed. Articles were selected for review based on their pertinence to the aforementioned topics.

Results

We discuss the ability of MR imaging to identify why a patient’s arthroplasty may have failed. Specific causes including component loosening and implant failure, rotator cuff and deltoid integrity, infection, subtle fractures, and nerve pathology are reviewed, with illustrative sample images.

Conclusion

MRI is a valuable tool in the assessment for pathology in the shoulder following arthroplasty.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11420-014-9399-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: MRI, shoulder arthroplasty, multiacquisition variable-resonance image combination (MAVRIC)

Introduction

Due to advancements in metal artifact reduction techniques, magnetic resonance (MR) imaging of the painful failed shoulder arthroplasty is a useful imaging technique to assess the integrity of the supporting soft-tissue sleeve and the implant, with the ability to provide information not otherwise afforded by other imaging modalities. The focus of this review is to illustrate the benefits of MR imaging to the clinician, whether used alone or as an adjunct to other imaging modalities, during the complex decision-making process while managing a painful shoulder arthroplasty. We will discuss the ability of MR imaging to identify why a patient’s shoulder arthroplasty may have failed, specifically by reviewing component loosening and implant failure, the integrity of the rotator cuff and deltoid, infection, subtle fractures, and nerve pathology.

Methods

A PubMed (MEDLINE) literature search focusing on the complications and imaging assessment of shoulder arthroplasty was performed. Specific keywords included “complications of shoulder arthroplasty,” “imaging of shoulder arthroplasty,” “MRI of arthroplasty,” “MAVRIC” and “SEMAC.” Over 2,600 articles were produced, of which 33 were selected for review based on their pertinence to the aforementioned topics.

Results

Preliminary imaging to evaluate the painful shoulder arthroplasty is performed with radiographs, and sometimes computed tomography (CT), ultrasound, and, if infection is being considered, occasional nuclear scintigraphy. At times, these modalities fail to identify the source of the patient’s symptoms, and MR imaging may be performed to further evaluate for potential pathology, which can be particularly helpful when addressing a specific clinical question or if revision arthroplasty is being considered.

In total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA), the most common complications, in order of decreasing frequency, include component loosening, glenohumeral instability, periprosthetic fracture, rotator cuff tears, neural injury, infection, and deltoid muscle dysfunction [1]. These complications have been reported to occur up to 15 years postoperatively as documented by studies with longer-term follow-up [1].

Implant loosening, instability, and periprosthetic fracture are typically evaluated radiographically or with CT [18, 6, 22]. However, MRI is able to provide superior assessment of the surrounding soft-tissue structures regarding the integrity of the rotator cuff, deltoid, and neural structures, as well as the joint capsule and synovium [29]. With advances in metal suppression imaging techniques, osteolysis and loosening are also readily evaluated on MRI [29], as are other changes of wear-induced synovitis. The integrity of the rotator cuff is typically evaluated with ultrasound, as it has been shown to be accurate in the postoperative shoulder [21, 10], and tears have been found by sonography in >50% of symptomatic postarthroplasty shoulders [11]. Less commonly, MRI may be used to evaluate occult fractures and potential concomitant soft-tissue pathology. At times, neural pathology may be evaluated in the assessment of distributional muscle atrophy or weakness. Ultimately, MRI can provide useful information regarding the postarthroplasty shoulder and aids in determining the need for revision.

The reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (rTSA) is used in the treatment of rotator cuff arthropathy, severe proximal humeral fractures with greater tuberosity malposition or nonunion, massive rotator cuff tear, and as a salvage procedure for failed total shoulder arthroplasty [1, 7]. Complications inherent to the rTSA such as scapular notching, glenoid dissociation, glenohumeral dislocation, and acromion and scapular spine fracture are adequately evaluated on conventional radiographs and CT [15, 6]. However, MRI in rTSA may prove useful in the assessment of neural injury and deltoid dysfunction. In addition, MRI can detect polyethylene dissociation, which is poorly evaluated on CT and X-ray.

Although less commonly performed in recent years, hemiarthroplasty was classically recommended over TSA in specific cases including inadequate glenoid bone stock, glenohumeral arthrosis in patients under the age of 50, and humeral head osteonecrosis with preserved glenoid cartilage [20, 1]. As an alternative to an implant with a polyethylene liner, the glenoid may be resurfaced with meniscal or tendon allograft, or capsular interposition [13]. In addition to the benefits described for total and reverse shoulder arthroplasty, MRI allows for evaluation of glenoid cartilage or biological glenoid resurfacing in patients with shoulder hemiarthroplasty (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Glenoid arthrosis in shoulder hemiarthroplasty. Axial PD MR images (a, b) in a patient with left shoulder pain show a left hemiarthroplasty with high-grade cartilage loss and exposed bone over the glenoid (black arrows). Synovitis is present, demonstrated by a fluid-distended pseudocapsule and thickened synovial lining (white arrows).

MRI Technique

Continuous modification of conventional pulse sequences and development of novel ones in recent years have significantly reduced metallic susceptibility artifact, such that MR imaging is commonly performed at our institution to identify complications following shoulder arthroplasty. Modifications include aligning the frequency-encoding gradient along the longitudinal axis of the prosthesis to reduce susceptibility artifact and choosing a smaller voxel size to improve spatial resolution at the artifact boundary [5, 30]. A wider receiver bandwidth increases readout gradient strength and thereby reduces the susceptibility artifact generated by the components. This will also concomitantly reduce interecho spacing, allowing for longer echo train lengths and decreased scan times [30]. Increasing the bandwidth, however, comes at the expense of decreased signal/noise ratio (SNR). To compensate for this, increasing the number of excitations (NEX) will increase the SNR but at the cost of longer scan times.

Imaging at 3.0 T should be avoided in arthroplasty, as susceptibility artifact is directly proportional to magnetic field strength. Gradient echo sequences are not used for arthroplasty imaging, as they lack the 180° refocusing pulse of a spin-echo sequence that is needed to compensate for signal loss from rapid intravoxel spin dephasing [19]. A short tau inversion recovery (STIR) sequence should be performed, as it is less sensitive to local field inhomogeneities in the presence of metallic hardware, thereby providing superior fat suppression compared with chemical shift selective fat suppression technique [2].

Relatively new and commercially available pulse sequences including slice-encoding metal artifact correction (SEMAC) and multiacquisition variable-resonance image combination (MAVRIC) techniques can further reduce susceptibility artifact around metal [12, 17]. The SEMAC technique utilizes robust slice encoding to correct metal artifacts by extending a view-angle-tilting (VAT) spin-echo (SE) sequence with additional z-phase encoding [17]. The MAVRIC sequence acquires multiple three-dimensional fast spin-echo (FSE) image datasets at different frequency bands, offset from the resonant proton frequency. It then combines these datasets to produce an image with markedly reduced susceptibility artifact [12, 8]. Reports in recent literature demonstrate MAVRIC as particularly useful for detecting periprosthetic osteolysis, synovitis, and supraspinatus tears by improving the conspicuity of the implant–bone and soft-tissue interfaces [9, 29].

A sample MRI protocol used at our institution (Table 1) includes oblique coronal and axial FSE proton density (PD) pulse sequences, as well as oblique coronal MAVRIC inversion recovery (IR) and PD sequences. To increase the sensitivity of identifying a subscapularis tendon tear and glenoid osteolysis, we perform a thin axial FSE PD sequence with limited craniocaudal coverage through these structures. An axial MAVRIC PD sequence may be obtained if there is specific clinical concern for osteolysis around the glenoid component and to potentially improve detection of a dehiscent subscapularis footprint. A sagittal FSE PD sequence extending medial to the glenoid fossa may occasionally be performed during troubleshooting or for a global assessment of the rotator cuff muscle quality.

Table 1.

Sample protocol for MRI of shoulder arthroplasty

| Timing parameters | Axial FSE PD | Coronal FSE PD | “Thin” axial FSE PD | MAVRIC coronal IR | MAVRIC coronal FSE PD | MAVRIC axial FSE PD (optional) | Sagittal FSE PD (optional) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TR (ms) | 4,000–6,000 | 4,000–6,000 | 4,000–6,000 | 4,000–6,000 | 4,000–6,000 | 4,000–6,000 | 4,000–6,000 |

| TE (ms) | 24 | 24 | 24 | 6–7 | 6–7 | 6–7 | 24 |

| Flip angle (degrees) | – | – | – | – | 110 | 110 | – |

| TI (ms) | – | – | – | 150 | – | – | – |

| ETL | 16 | 20 | 20 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 20 |

| RBW (kHz) | 125 | 125 | 125 | 125 | 125 | 125 | 125 |

| FOV (cm) | 20 | 20 | 20 | 24 | 24 | 26 | 20 |

| Matrix | 512 × 288 | 512 × 320 | 512 × 320 | 256 × 192 | 512 × 256 | 512 × 256 | 512 × 320 |

| Slice thickness (mm) | 3.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 2.0 |

| Interslice gap (mm) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| NEX | 3 | 4 | 4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 4 |

| Tailored RF | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | – | – | Yes |

| No phase wrapa | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | – | – | Yes |

| Variable BW | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Frequency direction | Right to left | Right to left | Right to left | Superior to inferior | Superior to inferior | Superior to inferior | Right to left |

| Approximate scan time (min) | 4.5–5.0 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 4.5–6.0 | 4.5–6.0 | 4.5–6.0 | 6.0 |

Position: neutral with the biceps tendon at 12:00. Patients are encouraged to breathe as much as possible using their abdominal muscles, in order to minimize excessive chest wall excursion. The reported RBW is reported as half bandwidth. To convert to BW per pixel, use the following formula: 2 × (half bandwidth)/(readout matrix)

FSE fast spin-echo proton, PD proton density, IR inversion recovery, MAVRIC multiacquisition variable-resonance image combination, BW bandwidth, ETL echo train length, FOV field of view, NEX number of excitations, RBW receiver bandwidth, RF radiofrequency, TE echo time, TI inversion time, TR repetition time

a“No phase wrap” is referred to as phase oversampling, depending on the vendor

MRI Assessment

Component Loosening and Implant Failure

Prosthetic loosening in shoulder arthroplasty more frequently affects the glenoid component [27], with various reported causes including aseptic osteolysis, infection, and soft-tissue instability [4]. The described patterns of glenoid component wear include superior and posterior implant tilt, as well as subsidence into the glenoid cavity [33]. Loosening of the glenoid component is usually apparent on radiographs, and CT can further aid determination of the wear pattern. Osteolysis and component loosening of both glenoid and humeral components may also be appreciated on MRI. A normal prosthesis should appear well incorporated with the adjacent bone on MRI (Fig. 2). In contrast, osteolysis appears as defined high signal surrounding the prosthesis, often delineated by a thin, low intensity rim (Figs. 3, 4 and 5). If this osteolysis is circumferential, loosening should be suspected.

Fig. 2.

Intact glenoid component in total shoulder arthroplasty. Axial PD MR image demonstrates a total shoulder arthroplasty with an intact glenoid component, which is incorporated into the adjacent bone (arrows).

Fig. 3.

Glenoid osteolysis. Axial PD MR image of a total shoulder arthroplasty reveals osteolysis around the glenoid peg, demonstrated by surrounding high signal intensity and delineated by a low-intensity rim (white arrows). Note the peg migration and endosteal erosion of the adjacent glenoid cortex (block arrow). The subscapularis is scarred to the anterior pseudocapsule (black arrows), and there is a moderate synovitis with internal particulate debris (asterisks).

Fig. 4.

Humeral osteolysis. Axial PD MR image of a total shoulder arthroplasty depicts osteolysis adjacent to the proximal humeral component (arrows). Osteolysis did not circumferentially surround the humeral prosthesis (not pictured) and therefore loosening was not suspected.

Fig. 5.

Glenoid osteolysis and loosening. Oblique coronal PD MR image (a) demonstrates circumferential osteolysis around the glenoid component (white arrows), indicating loosening. A characteristic wear-induced synovitis is noted in the axillary recess (black arrow). Frontal radiograph of the left shoulder (b) obtained at the same time reveals a less conspicuous lucent rim at the cement interface in the glenoid (black arrows).

In our experience, MR can reveal associated findings in cases of component loosening, including displacement or dislocation of the polyethylene liner (Figs. 6 and 7), component fracture (Fig. 8), wear-induced synovitis, and rotator cuff tears. Wear-induced synovitis occurs secondary to accumulation of particle debris from polyethylene breakdown, leading to a cytokine-mediated up-regulation of osteoclasts and down-regulation of osteoblasts, which may result in aseptic loosening. This synovitis is often intermediate signal intensity on PD images. A chronic wear-induced synovitis may result in indolent osseous erosion or osteolysis, demonstrated by focal loss of cortical bone adjacent to a distended joint capsule (Fig. 9). Adenopathy may also be seen in relation to wear-induced synovitis (Fig. 10) and is not specific to infection.

Fig. 6.

Glenoid component loosening and dislocation. Axial PD MR images (a, b) of a total shoulder arthroplasty reveal glenoid component loosening and anterolateral dislocation of the glenoid component (white arrows). There is a visible osseous defect in the glenoid (a, block arrow). The subscapularis tendon is scarred and chronically torn (black arrows). Synovitis and polymeric debris distend the pseudocapsule (white asterisks). Severe atrophy of the infraspinatus and subscapularis muscles is shown (black asterisks).

Fig. 7.

Glenoid component loosening and dislocation. Oblique sagittal PD MR images (c, d) of a total shoulder arthroplasty demonstrate an anteriorly dislocated and rotated glenoid component (a, block arrow), surrounded by a thick, patulous pseudocaspule (a, black arrows). There is frank osteolysis of the glenoid (b, white arrows). Severe subscapularis and infraspinatus muscle atrophy is shown (b, asterisks).

Fig. 8.

Glenoid component loosening and fracture. Axial PD MR image of a total shoulder arthroplasty in a patient staus post recent fall demonstrates loosening of the glenoid component with separation of the peg from the cement mantle (arrows). The glenoid peg is fractured (block arrow). An expanded, fluid, and polymeric debris-filled pseudocapsule is present (asterisk).

Fig. 9.

Wear-induced synovitis with osseous erosion. Axial PD (a) and oblique coronal MAVRIC PD (b) MR images of a total shoulder arthroplasty reveal intermediate intensity synovitis containing particulate polymeric debris (asterisk), distending a scarred axillary recess (black arrows). There is associated indolent periprosthetic erosion of the humerus and glenoid (white arrows), characteristic of a wear-induced synovitis.

Fig. 10.

Wear-induced synovitis with lymphadenopathy. Oblique coronal PD MR image (a) of a total shoulder arthroplasty demonstrates a particulate, intermediate intensity synovitis (asterisk) distending the axillary pouch (arrows). Oblique sagittal PD MR image (b) in the same patient reveals enlarged axillary lymph nodes, characteristic of a wear-induced synovitis. Note that lymphadenopathy may be seen in the absence of an infection.

Rotator Cuff Tear and Instability

MR imaging is a useful modality to evaluate the rotator cuff in patients who have undergone shoulder arthroplasty. Sperling et al. [29] suggested that MRI is an accurate and useful tool to determine the integrity of the rotator cuff in 21 shoulder arthroplasties. Further advances in MR techniques with the addition of MAVRIC led to a study by Hayter et al. [9], in which improved visualization of the supraspinatus tendon as a result of decreased image distortion allowed better detection of cuff tears.

Studies have indicated that glenohumeral instability is the second leading cause of complications associated with total shoulder arthroplasty, with anterior and superior instability accounting for 80% of instability cases [1]. Both osseous and soft-tissue factors play a role in postarthroplasty instability. Osseous factors such as glenoid deficiency, diminished humeral length, and component malrotation may be adequately assessed on radiographs and CT. However, soft-tissue factors are better depicted on MR imaging, with the focus of this section on imaging of the rotator cuff.

Radiographs are the initial imaging modality in evaluating instability and can infer a rotator cuff tear by the degree of subluxation of the humeral component in the coronal and axillary planes, although the deficient soft-tissue structure is not directly assessed. Ultrasound has been shown to be accurate in the detection of rotator cuff tears in the postoperative shoulder [31, 26]; however, ultrasound is unable to provide a global assessment of the shoulder. MR imaging is not intended to replace, but rather, complement other imaging modalities in the assessment of rotator cuff tears by demonstrating the degree of tendon retraction and, importantly, revealing the quality of the muscle, meanwhile providing a global evaluation of the integrity of the implant that may not otherwise be afforded by standard radiographs or ultrasound alone.

Failure of the subscapularis repair and anterior aspect of the capsule is a common late and perhaps under-recognized cause of anterior instability following shoulder arthroplasty [1, 27], which is best detected on a thin section axillary PD sequence. In cases with large size cobalt chromium heads, the footprint of the subscapularis and the lesser tuberosity may be obscured by susceptibility artifact but the remainder of the tendon, its muscle tendon junction, and its muscle belly are nearly always adequately visualized. The dehiscent subscapularis tendon may be seen retracted medially (Fig. 11) or as a longitudinally stripped thin tendon remnant often scarred to the anterior capsule. A subscapularis tendon tear is important to recognize early, as the subscapularis can be directly repaired. Fatty infiltration of the muscle belly is readily detected on MR imaging and may be of particular relevance in decision making regarding potential repair, reconstruction or conversion to rTSA.

Fig. 11.

Subscapularis tendon dehiscence. Axial PD MR image in a patient with shoulder instability following arthroplasty reveals subscapularis tendon dehiscence (arrows) with medial retraction to the glenoid rim.

The integrity of the anterior deltoid is important to assess in anterior instability, and MR imaging is capable of evaluating the deltoid origin for dehiscence and denervation. It is particularly important to evaluate the anterior deltoid if the patient is undergoing revision to reverse TSA, as it functions as a primary lever arm.

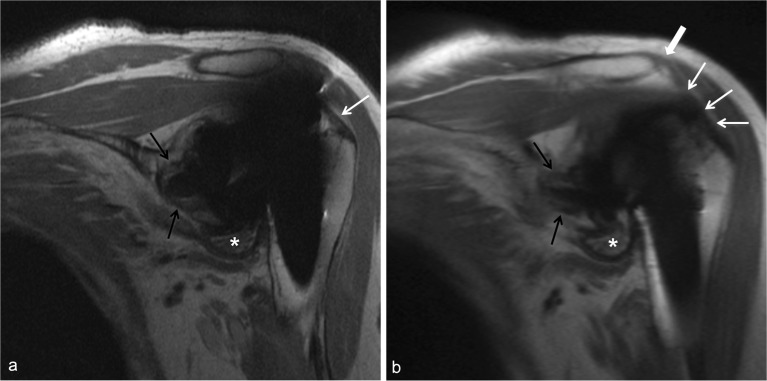

Evaluation of the supraspinatus tendon, at times, can prove to be challenging if using standard FSE techniques alone due to its close proximity to the humeral head component, which generates the susceptibility artifact superiorly, thereby obscuring the muscle tendon junction (Figs. 12a and 13a). Visualization of the distal tendon footprint, however, is often preserved. MAVRIC enables increased visibility of the cuff, particularly at the supraspinatus myotendinous junction (Fig. 12b) and may reveal tendon tears (Fig. 13b). The infraspinatus and teres minor tendons are typically less affected by metallic susceptibility created by the humeral head component.

Fig. 12.

MRI appearance of the supraspinatus and deltoid in total shoulder arthroplasty. Oblique coronal PD MR image (a) demonstrates incomplete visualization of the supraspinatus tendon at the footprint (white arrow) related to susceptibility artifact. Oblique coronal MAVRIC PD image (b) allows for complete visualization of the intact supraspinatus tendon and myotendinous junction (white arrows). An intact deltoid attachment is also well visualized (b, block arrow). There is circumferential glenoid osteolysis (black arrows) and a wear-induced synovitis in the axillary recess (asterisks).

Fig. 13.

MRI appearance of rotator cuff tear in total shoulder arthroplasty. Oblique coronal PD MR image (a) demonstrates incomplete visualization of the supraspinatus tendon related to susceptibility artifact, with severe tendinosis at the footprint (black arrow). Oblique coronal MAVRIC PD sequence (b) allows for detection of a high grade articular sided tear of the supraspinatus tendon (white arrow) and a non-retracted tendon (block arrow). Severe insertional tendinosis is also visible (black arrow).

Trauma and Periprosthetic Fracture

Periprosthetic fracture is a relatively rare complication, with intraoperative fractures more common than postoperative fractures [1, 25]. Fracture at the time of surgery is usually apparent intraoperatively, and there is an increased risk with removal of the humeral component during revision surgery [3]. Postoperative fractures of the acromion and scapular spine are among common complications of the rTSA [7, 32]. Fractures of the acromion may occur after trauma or vigorous activity, or as a stress fracture due to chronic, repetitive injury. Radiographs function as the mainstay in the imaging evaluation of periprosthetic fracture. However, when findings are equivocal on radiographs, MR can elucidate subtle, nondisplaced fracture lines appearing as linear intraosseous low signal intensity, as well as reactive bone marrow edema pattern seen in fracture or contusion (Fig. 14). In addition, MRI in acute trauma may also detect unsuspected component dislocation or fracture, as well as soft-tissue injuries (Fig. 15).

Fig. 14.

Periprosthetic fracture in shoulder arthroplasty. Oblique coronal PD MR (a) and MAVRIC IR (b) MR images of a total shoulder arthroplasty in a woman following a recent fall demonstrate a greater tuberosity fracture line (black arrow). Cortical disruption is seen at the lateral cortex of the proximal humerus (a, white arrow). The fracture incites a severe bone marrow edema pattern (b, asterisk).

Fig. 15.

Traumatic humeral component dislocation. Axial PD MR images reveal posterior dislocation of the humeral head and prosthesis (a, black arrow) in a woman following a recent fall. There is loosening of the glenoid component with posterior rotation (a, white block arrow) and extrusion of cement into the anterior margin of the subscapularis bursa (a, black block arrow). The anterior joint capsule is scarred, thickened, and patulous (a, white arrows). There is a full-thickness rupture of the subscapularis tendon (b, arrowheads). Debris distends the long head of the biceps tendon sheath (b, black arrow).

Neural Pathology

The occurrence of neural injury following shoulder arthroplasty is rare but may be slightly increased in reverse TSA [14]. Relative arm lengthening in reverse TSA is thought to be a possible etiology for these injuries. Other reported causes include intraoperative factors such as retractor placement and interscalene nerve block, postoperative hematoma, cement extrusion, screw migration, and humeral shaft fracture [14]. Axillary neuropathy is most frequently reported in reverse TSA and is usually transient [14]. Other nerves that may be injured intraoperatively and following shoulder arthroplasty include the suprascapular nerve and the brachial plexus. Electromyography may determine which nerve is the source of neuropathy, but MRI detects morphological changes in the neural structures around the shoulder, as well as effects of muscular denervation. Screw migration into the spinoglenoid or suprascapular notches with resultant mass effect on neural structures is well visualized on MRI (Fig. 16). Extruded cement is also apparent on MRI as amorphous low-intensity material (Fig. 16), possibly resulting in mass effect or irritation of surrounding structures. Cysts and distended bursae may also produce mass effect on adjacent neurovascular bundles, clearly visible on MRI (Figs. 17 and 18).

Fig. 16.

Cement extrusion with neural irritation in shoulder arthroplasty. Axial PD MR images (a, b) demonstrate medial migration of the glenoid screw with cortical disruption (a, white arrow), allowing for extrusion of cement into the suprascapular and spinoglenoid notches (a, b, black arrows). Oblique coronal MAVRIC PD image (c) reveals the migrated glenoid screws (white arrow) displacing the neurovascular bundle in the spinoglenoid notch (black arrow). Severe supraspinatus and infraspinatus atrophy is present (a–c, asterisks). Axillary radiograph of the same shoulder (d) allows faint visualization of extruded cement (black arrows).

Fig. 17.

Spinoglenoid notch cyst with neural impingement. Axial (a) and oblique coronal (b) PD MR images reveal a cyst in the spinoglenoid notch (a, asterisk; b, white arrow) exerting mass effect on the suprascapular nerve (a, b, black arrows). Oblique coronal IR (c) and FSE (d) images demonstrate subacute denervation edema of the infraspinatus and teres minor muscle bellies (asterisks).

Fig. 18.

Brachial plexopathy. Sagittal PD MR image in a patient with right shoulder pain demonstrates a fluid distended subscapularis bursa (asterisk) exerting mass effect on the adjacent brachial plexus (arrow). Fatty atrophy of the infraspinatus muscle belly is shown (asterisk).

Infection

Infection is rare in shoulder arthroplasty, with an overall prevalence of 0–4%, but is diagnostically challenging for the clinician and potentially devastating for the patient [1, 24, 27]. Most patients do not present with clear signs of infection in shoulder arthroplasty. Initial evaluation with laboratory parameters including erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein levels, and white blood cell count are of limited predictive value, as they are often normal [28]. Less virulent organisms seen in the shoulder arthroplasty, particularly Propionibacterium acnes, make the diagnosis of infection challenging and unique compared with that seen in hip and knee arthroplasty [24]. Additional organisms following shoulder arthroplasty include coagulase-negative Staphylococcus and the more serious Staphylococcus aureus.

New osseous resorption, periosteal reaction, or frank loosening is considered associated with infection, until proven otherwise. Radiographs, and to a greater degree CT, can demonstrate periosteal reaction and osteolysis or loosening about one or both components suggestive of infection, but neither are sensitive or specific. Currently, combined leukocyte-marrow imaging is considered the most accurate of radionuclide imaging studies [16] and the gold standard for some periprosthetic infections; however, these techniques have mixed results for shoulder infections [24]. Ultimately, the diagnosis of infection relies on laboratory evaluation of synovial fluid and tissue cultures or frozen-section analysis.

Studies have shown that MR imaging is capable of detecting infection in knee arthroplasty with 86–92% sensitivity and 85–87% specificity, as reported by Plodkowski et al. [23] in 28 knees, characterized by a lamellated, thickened capsule with extracapsular soft-tissue edema. Although, there is no current literature demonstrating the detection of infection following shoulder arthroplasty by MR imaging, MRI is capable of revealing adenopathy, sinus tracts, fluid collections, and diffuse periarticular edema involving the soft tissues (Fig. 19). The joint line is often partially obscured by artifact; however, synovitis remains detectable and, although not described in the literature, the reactive synovitis in shoulder arthroplasty is more often nonspecific in appearance, probably due to the indolent nature of the organisms.

Fig. 19.

Infection of total shoulder arthroplasty. Coronal oblique MAVRIC IR (a) and PD (b) MR images demonstrate periprosthetic bone marrow edema (a, black arrows) and periarticular soft-tissue edema with involvement of the supraspinatus and deltoid muscle bellies (a, asterisks), characteristic of infection. A sinus tract is depicted anterolaterally (white arrows). Intraoperative cultures obtained during surgical debridement grew Staphylococcus aureus.

Conclusion

MR imaging of the postarthroplasty shoulder, as a result of advancements in metal artifact suppression techniques, is a useful imaging modality in the detection of the most common postoperative complications, including component loosening and osteolysis, instability, rotator cuff insufficiency, trauma, infection, and neuropathy. Ultimately, MR imaging can provide clinically pertinent information to help guide the orthopedic surgeon to determine the appropriate treatment strategy including the potential need for revision.

Electronic Supplementary Material

(PDF 1224 kb)

Acknowledgments

Disclosures

ᅟ

Conflict of Interest:

O. Kenechi Nwawka, MD, Gabrielle P. Konin, MD, and Darryl B. Sneag, MD, have declared that they have no conflict of interest. Hollis G. Potter, MD, receives grants from NIH and institutional research support from GEHC, outside the work. Lawrence V. Gulotta, MD, reports personal fees from Biomet, Inc, outside the work.

Human/Animal Rights:

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by the any of the authors.

Informed Consent:

N/A

Required Author Forms

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Bohsali KI, Wirth MA, et al. Complications of total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(10):2279–2292. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Del Grande F, Santini F, Herzka DA, et al. Fat-suppression techniques for 3-T MR imaging of the musculoskeletal system. Radiographics. 2014; 34(1): 217-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Favard L. Revision of total shoulder arthroplasty. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2013;99(1 Suppl):S12–S21. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2012.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flurin PH, Janout M, et al. Revision of the loose glenoid component in anatomic total shoulder arthroplasty. Bull Hosp Jt Dis. 2013;71(Suppl 2):68–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frazzini VI, Kagetsu NJ, et al. Internally stabilized spine: optimal choice of frequency-encoding gradient direction during MR imaging minimizes susceptibility artifact from titanium vertebral body screws. Radiology. 1997;204(1):268–272. doi: 10.1148/radiology.204.1.9205258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ha AS, Petscavage JM, et al. Current concepts of shoulder arthroplasty for radiologists: Part 2—anatomic and reverse total shoulder replacement and nonprosthetic resurfacing. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199(4):768–776. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.8855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harreld KL, Puskas BL, et al. Massive rotator cuff tears without arthropathy: when to consider reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(10):973–984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayter CL, Koff MF, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the postoperative hip. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2012;35(5):1013–1025. doi: 10.1002/jmri.23523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayter CL, Koff MF, et al. MRI after arthroplasty: comparison of MAVRIC and conventional fast spin-echo techniques. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197(3):W405–W411. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.6659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hennigan SP, Iannotti JP. Instability after prosthetic arthroplasty of the shoulder. Orthop Clin N Am. 2001;32(4):649–659. doi: 10.1016/S0030-5898(05)70234-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ives EP, Nazarian LN, et al. Subscapularis tendon tears: a common sonographic finding in symptomatic postarthroplasty shoulders. J Clin Ultrasound. 2013;41(3):129–133. doi: 10.1002/jcu.21980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koch KM, Lorbiecki JE, et al. A multispectral three-dimensional acquisition technique for imaging near metal implants. Magn Reson Med. 2009;61(2):381–390. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krishnan SG, Nowinski RJ, et al. Humeral hemiarthroplasty with biologic resurfacing of the glenoid for glenohumeral arthritis. Two to fifteen-year outcomes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):727–734. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.01291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ladermann A, Lubbeke A, et al. Prevalence of neurologic lesions after total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(14):1288–1293. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.00369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levigne C, Boileau P, et al. Scapular notching in reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Should Elb Surg. 2008;17(6):925–935. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Love C, Marwin SE, et al. Nuclear medicine and the infected joint replacement. Semin Nucl Med. 2009;39(1):66–78. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu W, Pauly KB, et al. SEMAC: slice encoding for metal artifact correction in MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2009;62(1):66–76. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merolla G, Di Pietto F, et al. Radiographic analysis of shoulder anatomical arthroplasty. Eur J Radiol. 2008;68(1):159–169. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Naraghi AM, White LM. Magnetic resonance imaging of joint replacements. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2006;10(1):98–106. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-934220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neer CS., 2nd Articular replacement for the humeral head. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1955;37-A(2):215–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neer CS, 2nd, Watson KC, et al. Recent experience in total shoulder replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64(3):319–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petscavage JM, Ha AS, et al. Current concepts of shoulder arthroplasty for radiologists: Part 1—Epidemiology, history, preoperative imaging, and hemiarthroplasty. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199(4):757–767. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.8854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Plodkowski AJ, Hayter CL, et al. Lamellated hyperintense synovitis: potential MR imaging sign of an infected knee arthroplasty. Radiology. 2013;266(1):256–260. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12120042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ricchetti ET, Frangiamore SJ, et al. Diagnosis of periprosthetic infection after shoulder arthroplasty. A critical analysis review. JBJS Rev. 2013;1(1):1–9. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.RVW.M.00055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh JA, Sperling J, et al. Periprosthetic fractures associated with primary total shoulder arthroplasty and primary humeral head replacement: a thirty-three-year study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(19):1777–1785. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sofka CM, Adler RS. Original report. Sonographic evaluation of shoulder arthroplasty. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180(4):1117–1120. doi: 10.2214/ajr.180.4.1801117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sperling JW, Hawkins RJ, et al. Complications in total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(6):563–569. doi: 10.2106/00004623-201303200-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sperling JW, Kozak TK, et al. Infection after shoulder arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001; 382(1): 206-216. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Sperling JW, Potter HG, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of painful shoulder arthroplasty. J Should Elb Surg. 2002;11(4):315–321. doi: 10.1067/mse.2002.124426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suh JS, Jeong EK, et al. Minimizing artifacts caused by metallic implants at MR imaging: experimental and clinical studies. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171(5):1207–1213. doi: 10.2214/ajr.171.5.9798849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teefey SA, Hasan SA, et al. Ultrasonography of the rotator cuff. A comparison of ultrasonographic and arthroscopic findings in one hundred consecutive cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82(4):498–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walch G, Mottier F, et al. Acromial insufficiency in reverse shoulder arthroplasties. J Should Elb Surg. 2009;18(3):495–502. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walch G, Young AA, et al. Patterns of loosening of polyethylene keeled glenoid components after shoulder arthroplasty for primary osteoarthritis: results of a multicenter study with more than five years of follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(2):145–150. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.00699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 1224 kb)