Abstract

Objectives

An assessment of temporal trends in patient survival is important to determine the progress towards patient outcomes and to reveal where advancements must be made. This study assessed temporal changes spanning 22 years in demographics, clinical characteristics, and overall survival of small cell lung cancer (SCLC) patients.

Materials and methods

This analysis included 1,032 SCLC patients spanning two time-periods from the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute: 1986 to 1999 (No. = 410) and 2000 to 2008 (No. = 622). Kaplan-Meier survival curves and log-rank statistics were used to assess survival rates across the two time-periods and multivariable Cox proportional hazards models were used to generate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results

The overall 5-year survival rate significantly increased from 8.3% for the 1986 to 1999 time-period to 11.0% (P < 0.001) for the 2000 to 2008 time-period, and the median survival time increased from 11.3 months (95% CI 10.5–12.7) to 15.2 months (95% CI 13.6–16.6) We also observed significant increases in stage-specific median survival times and survival rates across the two time-periods. A multivariable Cox proportional hazards model for the entire cohort revealed significant increased risk of death for patients diagnosed in 1986 to 1999 (HR = 1.29; 95% CI 1.11 – 1.49), patients diagnosed between 60 and 69 years of age (HR = 1.33; 95% CI 1.04 – 1.49) and over 70 years of age (HR = 1.63; 95% CI 1.26 – 2.11), men (HR = 1.33; 95% CI 1.16 – 1.53), patients with no first course treatment (HR = 2.17; 95% CI – 3.00) and extensive stage SCLC (HR = 2.79; 95% CI 2.35 – 3.30)

Conclusion

This analysis demonstrated significant improvements in overall and stage-specific median survival times and survival rates of SCLC patients treated at the Moffitt Cancer Center from 1986 to 2008.

Keywords: Lung cancer, Survival, Small cell lung cancer, epidemiology, Cancer registry

1. Introduction

In the United States, lung cancer accounts for more deaths than any other cancer in both men and women. In 2013 there was an estimated 159,480 deaths in US, accounting for about 27% of all cancer deaths1. Small cell lung cancer (SCLC), accounting for approximately 15% of all lung cancer diagnoses, has steadily decreased in the US over the last several decades which has been attributed to decreasing numbers of smokers and changes in cigarette composition2,3. Compared to the more prevalent non-small-cell lung cancer, SCLC is distinct because of its rapid doubling time, high growth fraction, early development of widespread metastases, and dramatic initial response to chemotherapy and chest radiation4. However, despite high initial response to therapy, most patients die from recurrent disease. SCLC has a grim prognosis with a median survival of approximately < 4 months when untreated and a 5-year survival rate of approximately 6% when treated5. A recent report from the American College of Chest Physicians6 reported that median survival for limited stage disease is 18 to 24 months with a 5-year survival of 20% to 25%, while median survival for extensive stage disease is 9 to 10 months with only 10% of patients alive at 2 years. SCLC survival has not changed considerably over the last several decades, and screening and early diagnosis of SCLC has not yielded promising results7.

An assessment of historical trends in cancer survival is an important evaluation to determine the progress towards patient outcomes and to reveal where advancements must be made. To date, few studies have evaluated survival trends of SCLC patients. The goal of this study was to assess temporal changes in demographics, clinical characteristics, and overall survival of SCLC patients seen at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study population

This analysis included 1,032 SCLC patients who were treated at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute between 1986 and 2008. The two periods that were selected for analysis were: 1986 to 1999 (No. = 410) and 2000 to 2008 (No. = 622). These two time-period ranges were selected to divide the study population to provide reasonable sample sizes to compare changes in demographics and overall survival across decades. This research was approved by the University of South Florida Institutional Review Board.

2.2. Cancer registry data

The primary source of data for this analysis was Moffitt’s Cancer Registry which abstracts information from patient electronic medical records on demographics, history of smoking, diagnostic testing, stage of disease, histology, and treatment. Follow-up for survival and vital status information occurs annually through passive and active methods. Summary of first course of treatment” is defined as all methods of treatment recorded in the treatment plan and administered to the patient before disease progression, recurrence, or death. For this analysis, “documented comorbidities” was a summary covariate for one or more documented comorbidities including cardiovascular disease (CVD), lung/pulmonary diseases, metabolic disorders, effusion, anemia, liver conditions, kidney conditions, or neurological conditions. We also created a summary covariate for site of radiation therapy among patients receiving radiation and chemotherapy and with or without any other modality. Site(s) of radiation therapy was categorized by: brain only, lung only, only brain and lung, and a combined group of lung and other, brain and other, or other sites. A summary covariate for first line chemotherapy treatment was created for patients receiving chemotherapy with the following categories: Cyclophosphamide, Adriamycin, and vincristine (CAV); Carboplatin and Etoposide ± other; Cisplatinum and Etoposide ± other; and other.

A staging system for SCLC was introduced by the Veterans Administration Lung Study Group (VALG) that classifies patients into two categories, limited stage (LS) disease or extensive stage (ES) disease, depending on whether the tumor could be treated within a single radiotherapy portal or not 8. The Cancer Registry uses a SCLC summary staging system, as supported by the Surveillance, Epidemiologic, and End Results (SEER) program2, that categorizes the local (cancer is limited to the organ in which it began, without evidence of spread), regional (cancer has spread beyond the primary site to nearby lymph nodes or tissues and organs), and distant extent of the tumor (cancer has spread from the primary site to distant tissues or organs or to distant lymph nodes). For this analysis local and regional disease treated with radiochemotherapy, surgery and chemotherapy, or radiation only were classified as LS-SCLC and distant disease treated with chemotherapy only or surgery and chemotherapy were classified as ES-SCLC. For those patients with unknown/missing summary staging data, we used the American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM staging data9 and classified stages IA to IIIB as LS-SCLC and stage IIIB without effusion as LS-SCLC, stage IIIB with effusion as ES-SCLC, and stage IV as ES-SCLC. Patients lacking adequate summary staging data and TNM staging data were categorized as ‘not classifiable’ and analyzed as separately.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Pearson’s chi-square was used to test for differences in the patient characteristics by the two time groups. Overall survival, which was defined as date of diagnosis to date of death or last follow-up, was right-censored and survival analyses were performed using Kaplan-Meier survival curves and the log-rank statistic. Multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression utilized to generate hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for each time-period and a single model for the entire cohort. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary NC).

3. Results

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the SCLC patients for each time-period are presented in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences between the two time-periods for the demographics and diagnostic testing. Conversely, there were significant differences between the two time-periods for stage, summary of first course treatment, site(s) of radiation therapy, and first line chemotherapy treatment. In the 1986 to 1999 time-period, 55.1% had ES-SCLC disease, 35.6% had chemotherapy only for first course treatment, 26.0% had brain and lung radiation therapy, and 29.6% first line chemotherapy treatment with Carboplatin and Etoposide. In the 2000 to 2008 time-period, 35.1% had ES-SCLC disease, 24.3% had chemotherapy only for first course treatment, 45.4% had brain and lung radiation therapy, and 57.9% had first line chemotherapy treatment with Carboplatin and Etoposide. Because there were no data available on presence of comorbidities in the 1986 to 1999 time-period, we did not calculate a p-value.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the small cell lung cancer patients for each time-period

| Characteristic | 1986 to 1999 (N = 410) |

2000 to 2008 (N = 622) |

P-value1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, N (%) | |||

| < 50 | 39 (9.5) | 63 (10.1) | |

| ≥ 50 to ≤ 59 | 92 (22.4) | 159 (25.6) | |

| ≥ 60 to ≤ 69 | 154 (37.6) | 232 (37.3) | |

| ≥ 70 | 125 (30.5) | 168 (27.0) | 0.543 |

| Gender, N (%) | |||

| Male | 212 (51.7) | 306 (49.2) | |

| Female | 198 (48.3) | 316 (50.8) | 0.468 |

| Smoking status, N (%) | |||

| Never | 7 (1.7) | 10 (1.6) | |

| Former | 160 (39.0) | 254 (40.8) | |

| Current | 230 (56.1) | 296 (47.6) | 0.2923 |

| Unknown | 13 (3.2) | 62 (10.0) | |

| Race, N (%) | |||

| White | 400 (97.6) | 600 (96.5) | |

| Black | 8 (2.0) | 14 (2.3) | 0.9012 |

| Other or unknown | 2 (0.5) | 8 (1.3) | |

| Ethnicity, N (%) | |||

| Non-Hispanic | 396 (97.1) | 595 (96.9) | |

| Hispanic | 11 (2.7) | 16 (2.6) | 0.9993 |

| Unknown | 1 (0.2) | 7 (1.1) | |

| Stage, N (%) | |||

| Limited | 164 (40.0) | 218 (50.3) | |

| Extensive | 226 (55.1) | 313 (35.1) | |

| Not classifiable | 20 (4.9) | 91 (14.6) | < 0.001 |

| Documented comorbidities 4 , N (%) | |||

| None reported | 410 (100) | 534 (85.9) | |

| Reported | 0 (0.0) | 88 (14.2) | NC |

| Diagnostic testing, N (%) | |||

| Cytology | 55 (13.4) | 87 (14.0) | |

| Histology | 355 (86.6) | 485 (78.0) | 0.2733 |

| Missing/unknown | 0 (0.0) | 50 (8.0) | |

| Summary of first course treatment 5 , N (%) | |||

| Radiation and chemotherapy only | 197 (48.1) | 273 (43.9) | |

| Chemotherapy only | 146 (35.6) | 151 (24.3) | |

| Surgery ± chemotherapy ± radiation ± other | 37 (9.0) | 87 (14.0) | |

| Chemotherapy ± radiation ± other | 10 (2.4) | 23 (3.7) | |

| None | 20 (4.9) | 28 (4.5) | 0.004 3 |

| Missing/unknown | 0 (0.0) | 60 (9.7) | |

|

Site(s) of radiation therapy among patients receiving

radiation and chemotherapy ± other, N (%) |

|||

| Brain only | 25 (11.0) | 44 (12.6) | |

| Lung only | 103 (45.4) | 115 (32.9) | |

| Brain and lung only | 59 (26.0) | 159 (45.4) | |

| Lung and other or Brain and other or Other | 40 (17.6) | 32 (9.1) | < 0.001 |

|

First line chemotherapy treatment among patients

chemotherapy ± other |

|||

| Cyclophosphamide, Adriamycin, and vincristine (CAV) ± other |

84 (22.6) | 3(0.6) | |

| Carboplatin and Etoposide ± other | 110 (29.6) | 303 (57.9) | |

| Cisplatinum and Etoposide ± other | 168 (45.2) | 176 (33.6) | |

| Other | 10 (2.7) | 42 (8.0) | < 0.001 |

Abbreviations: NC, not calculated

P-value calculated from the Pearson’s chi-square to test for differences in the characteristics across the two time groups

P-value excludes “Other or unknown” group

P-value excludes “Unknown” group

A summary of one or more documented comorbidities including cardiovascular diseases, lung/pulmonary diseases, metabolic disorders, effusion, anemia, liver conditions, kidney conditions, or neurological conditions.

First course of treatment includes all methods of treatment recorded in the treatment plan and administered to the patient before disease progression or recurrence.

Supplemental Table 1 presents the demographic and clinical characteristics by stage of disease and revealed significant differences for summary of first course treatment, site(s) of radiation therapy, and first line chemotherapy treatment.

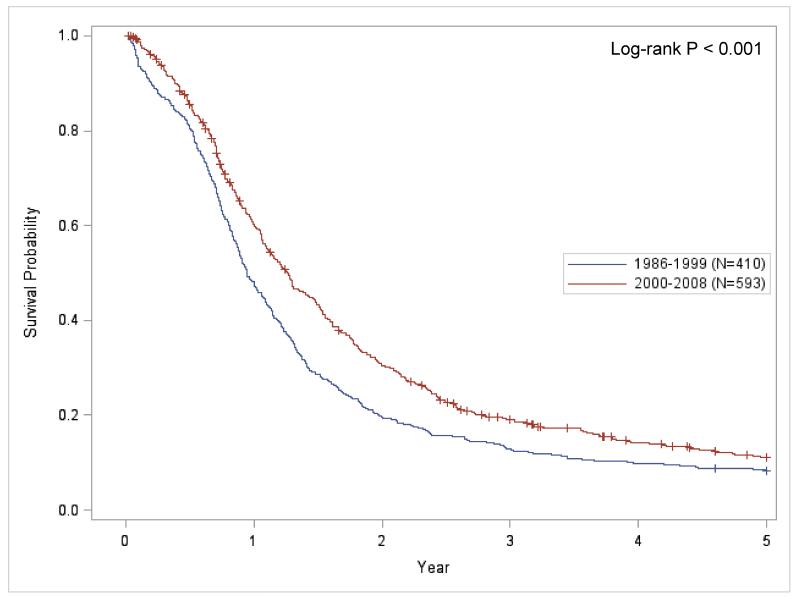

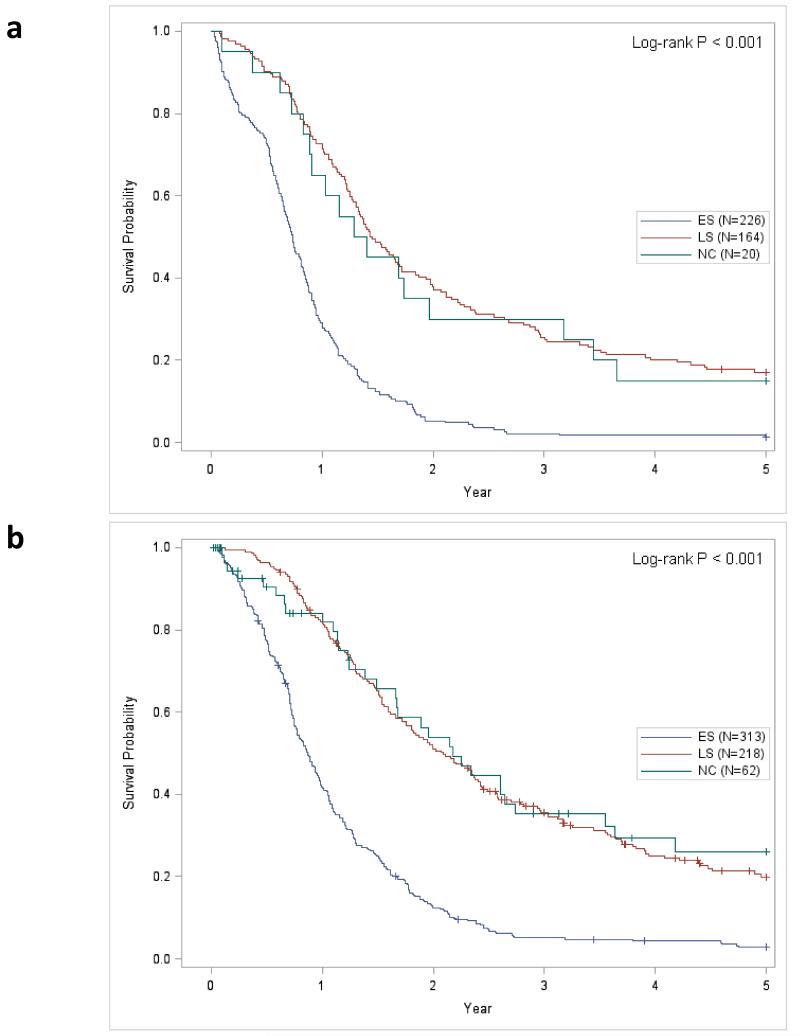

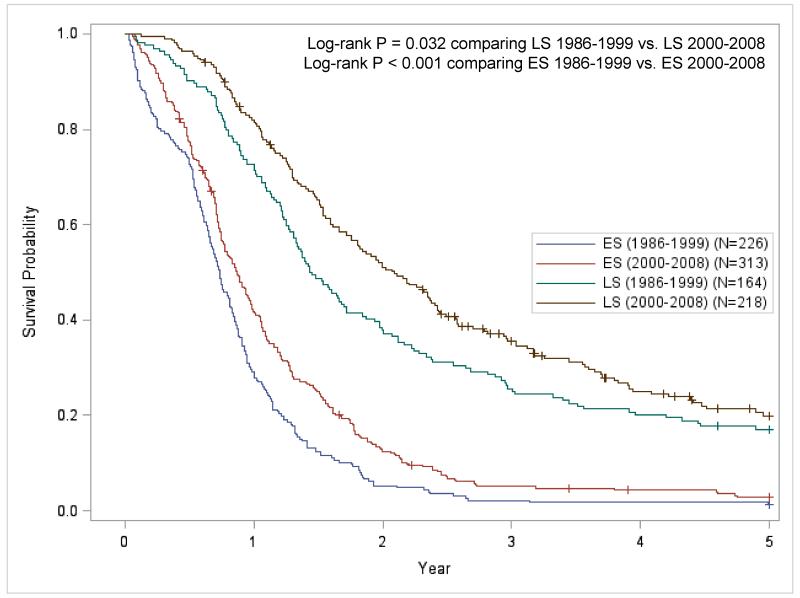

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for each time-period and demonstrates that the 2000 to 2008 time-period has significantly better survival than the 1986 to 1999 time-period (Figure 1; P < 0.001). Figures 2A and 2B present the stage-specific survival for the 1986 to 1999 and 2000 to 2008 time-periods, respectively. For both time-periods, LS-SCLC patients had significantly improved survival compared to ES-SCLC disease patients. When ‘not classifiable’ staging was excluded (Figure 3), the stage-specific survival demonstrated that patients from the 2000 to 2008 period has significantly improved survival compared to the 1986 to 1999 period for LS-SCLC (P = 0.032) and ES-SCLC patients (P < 0.001),

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival plot comparing 5-year survival for each time-period for all small cell lung cancer patients (‘+’ = Censored event).

Figure 2.

Stage-specific Kaplan-Meier survival curves comparing stage-specific for each time-period (‘+’ = Censored event.) Figure 2A. Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the 1986 to 1999 time-period; Figure 2B Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the 2000 to 2008 time-period. Abbreviations: LS, limited stage disease; ES, extensive stage disease; NC, not classifiable histology.

Figure 3.

Stage-specific Kaplan-Meier survival curves comparing stage-specific 5-year survival for each time-period (‘+’ = Censored). The patients with ‘not classified’ histology have been excluded. Abbreviations: LS, limited stage disease; ES, extensive stage disease

Across the two time-periods, the overall median survival time increased from 11.3 months (95% CI 10.5 – 12.7) to 15.2 months (95% CI 13.6 – 16.6). For all SCLC patients, 1-year (48.1% to 60.1%), 2.5-year (15.9% to 22.6%), and 5-year survival (8.3% to 11.0%) rates significantly improved across the two time-periods (Table 2). Among LS-SCLC patients, the median survival time increased from 17.3 months (95% CI 25.1) to 25.1 months (95% CI 21.1 – 28.8) and the 1-year (72.6% to 82.0%), 2.5-year (31.1% to 40.7%), and 5-year survival (17.1% to 19.9%) rates significantly improved across the two time-periods. Among ES-SCLC patients, the median survival time increased from 8.8 months (95% CI 7.9 – 9.8) to 10.4 years (95% CI 9.2 – 11.6) and the survival rates significantly improved from 28.8% to 41.8% for the 1-year survival rate, 3.6% to 6.8% for the 2.5-year survival rate, and 1.3% to 2.8% for the 5-year survival rate.

Table 2.

Median survival time and 1-year, 2.5-year, and 5-year survival rate for each time-period3

| 1986 to 1999 (N = 410) |

2000 to 2008 (N = 593)3 |

P-value2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median survival time, months (95% CI) 1 | |||

| Overall | 11.3 (10.5 – 12.7) | 15.2 (13.6 – 16.6) | |

| By stage | |||

| Limited | 17.3 (15.7 – 20.6) | 25.1 (21.1 – 28.8) | |

| Extensive | 8.8 (7.9 – 9.8) | 10.4 (9.2 – 11.6) | |

| Not classifiable | 16.1 (10.0 – 38.2) | 26.1 (20.0 – 32.9) | |

| 1-year survival rate, % | |||

| Overall | 48.1 | 60.1 | < 0.001 |

| By stage | |||

| Limited | 72.6 | 82.0 | 0.022 |

| Extensive | 28.8 | 41.8 | 0.001 |

| Not classifiable | 65.0 | 81.8 | 0.172 |

| 2.5-year survival rate, % | |||

| Overall | 15.9 | 22.6 | < 0.001 |

| By stage | |||

| Limited | 31.1 | 40.7 | 0.009 |

| Extensive | 3.6 | 6.8 | < 0.001 |

| Not classifiable | 30.0 | 44.6 | 0.162 |

| 5-year survival rate, % | |||

| Overall | 8.3 | 11.1 | < 0.001 |

| By stage | |||

| Limited | 17.1 | 19.9 | 0.032 |

| Extensive | 1.3 | 2.8 | < 0.001 |

| Not classifiable | 15.0 | 26.1 | 0.178 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval

Bold p-values indicate a statistically significant difference across the two time-periods

Median survival time and corresponding confidence intervals were calculated from the Kaplan–Meier survival curves that were right-censored at 5-years.

P-values calculated from the log-rank test

Complete follow-up data were not available on all patients. Samples sizes are based on number of patients with available vital status and follow-up information.

Table 3 presents the multivariable hazard ratios (mHRs) models for all covariates for each time-period and a single model for the entire cohort of SCLC patients from 1986 to 2008. Patients with unknown smoking status were excluded from these analyses. Since there were few never smokers, we combined never and former smokers into the referent group. For both time-periods, a statistically significant increased risk of death was observed for men and patients with ES-SCLC. In the multivariable model for the entire cohort that included time-period as a covariate, we observed a statistically significant increased risk of death for patients diagnosed in 1986 to 1999 (HR = 1.29; 95% CI 1.11 – 1.49), patients diagnosed between 60 and 69 years of age (HR = 1.33; 95% CI 1.04 – 1.49) and over 70 years of age (HR = 1.63; 95% CI 1.26 – 2.11), men (HR = 1.33; 95% CI 1.16 – 1.53), patients with no first course treatment (HR = 2.17; 95% CI – 3.00) and ES disease (HR = 2.79; 95% CI 2.35 – 3.30). Interestingly, the multivariable model for the entire cohort also revealed a significantly decreased risk of death among patients surgery ± chemotherapy ± radiation ± other (HR = 0.69; 95% CI 0.55 – 0.88).

Table 3.

Multivariable Cox proportional hazard models for each time-period and for the entire cohort3

| 1986 to 1999 (N = 397)1 |

2000 to 2008 (N = 560)1 |

1986 to 2008 (N = 957)2 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) |

| Time-period | |||

| 2000 to 2008 | -- | -- | 1.00 (referent) |

| 1986 to 1999 | -- | -- | 1.29 (1.11 – 1.49) |

| Age, N (%) | |||

| < 50 | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| ≥ 50 to ≤ 59 | 1.16 (0.76 – 1.78) | 0.98 (0.70 – 1.35) | 1.04 (0.80 – 1.34) |

| ≥ 60 to ≤ 69 | 1.86 (1.23 – 2.80) | 1.06 (0.77 – 1.46) | 1.33 (1.04 – 1.69) |

| ≥ 70 | 2.32 (1.52 – 3.54) | 1.29 (0.92 – 1.81) | 1.63 (1.26 – 2.11) |

| Gender, N (%) | |||

| Female | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| Male | 1.30 (1.05 – 1.60) | 1.41 (1.17 – 1.70) | 1.33 (1.16 – 1.53) |

| Smoking status, N (%) | |||

| Never and Former | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| Current | 1.47 (1.18 – 1.84) | 1.15 (0.95 – 1.39) | 1.30 (1.12 – 1.50) |

| Diagnostic test | |||

| Histology | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| Cytology | 0.82 (0.59 – 1.13) | 1.53 (1.19 – 1.98) | 1.15 (0.94 – 1.40) |

| Missing/unknown | -- | 2.76 (0.38 – 19.98) | 2.35 (0.33 – 16.85) |

| Summary of first course treatment | |||

| Radiation and chemotherapy only | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| Chemotherapy only | 1.00 (0.78 – 1.29) | 1.33 (1.06 – 1.69) | 1.15 (0.97 – 1.37) |

| Surgery ± chemotherapy ± radiation ± other |

0.41 (0.26 – 0.64) | 0.97 (0.74 – 1.29) | 0.69 (0.55 – 0.88) |

| Chemotherapy ± radiation ± other | 1.48 (0.64 – 3.42) | 0.83 (0.53 – 1.32) | 0.83 (0.56 – 1.23) |

| None | 1.69 (0.96 – 2.94) | 3.33 (2.19 – 5.07) | 2.17 (1.57 – 3.00) |

| Missing/unknown | -- | 0.15 (0.04 – 0.63) | 0.17 (0.41 – 0.67) |

| Stage, N (%) | |||

| Limited | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| Extensive | 2.96 (2.28 – 3.84) | 2.83 (2.25 – 3.55) | 2.79 (2.35 – 3.30) |

| Not classifiable | 0.79 (0.41 – 1.52) | 1.31 (0.89 – 1.94) | 1.08 (0.78 – 1.49) |

Abbreviations: HR, Hazard Ratio; CI, confidence interval

Bold HRs indicate a statistically significant result

Patients with unknown smoking status were excluded (N = 13 for 1986 to 1999 and n = 62 for 2000 to 2008)

Patients with unknown smoking status were excluded (N = 75)

Complete follow-up data were not available on all patients. Samples sizes are based on number of patients with available vital status and follow-up information.

4. Discussion

This analysis of Cancer Registry data from a tertiary Comprehensive Cancer Center demonstrates statistically significantly improved survival of SCLC patients over the past 22 years. Specifically, we observed statistically significant increases in overall and stage-specific median survival time and 1-, 2.5- and 5-year survival rates across two time-periods (i.e., 1986 to 1999 vs. 2000 to 2008).

A SEER monograph on lung cancer published in 2007 reported overall and stage-specific survival rates based on SCLC patients diagnosed between 1998 and 2001 from 12 SEER areas10. We explored the 1998 to 2001 time-period in our data so we could make comparisons to the SEER findings. For SCLC patients diagnosed between 1998 and 2001, the overall 5-year survival for SEER was 6.0% (N = 33,008) vs. 8.5% (N = 507) in our data. The SEER monograph also performed stage-specific analyses using the TNM staging classification rather than the two-stage classification scheme as presented in this manuscript and routinely used for the clinical staging of SCLC6. TNM staging was available on a subset of the SCLC patients in this analysis, so we generated stage-specific rates for the 1998 to 2001 time-period. The stage-specific rates in the SEER study vs. our study were 31.4% vs. 36% for stage I, 19.3% vs. 17.7% for stage II, 8.4% vs. 12.1% for stage III, and 2.2% vs. 3.9% for stage IV. Thus, the SEER results are comparable with the rates found in our analysis.

There have been numerous studies that have assessed temporal trends in the incidence and mortality of SCLC2,3,11-16; however, to date there have been few studies to assess temporal changes in survival of SCLC patients2,17-19. Three studies17-19 were published over 24 years ago and all demonstrated improved survival rates over time. A more recent SEER study evaluated sex- and stage-based differences in the incidence and survival of SCLC over a 30 period from 1973 to 2002 and found a modest but statistically significant improvement in survival among both limited-stage SCLC and extensive-stage disease2. Specifically, the 2-year survival for patients with ES-SCLC was 1.5% in 1973 and improved to 4.6% by 2000 and the 5-year survival rate for patients with LS-disease increased from 4.9% in 1973 to 10% in 1998. In a previous study20 we found significant differences in demographic characteristics of non-small cell lung cancer patients from the same time span of this analysis (1986 to 2008). Specifically, the percentage of patients who were diagnosed over the age of 70 years increased from 19.8% to 38.4%, the percentage of women increased from 35.7% to 50.9%, and the percentage of current smokers decreased from 47.8% to 28.3%. Interestingly, in the current analysis there were no differences between the two time-periods for the demographic characteristics of SCLC patients. This suggests that the demography of non-small cell lung cancer patients has changed over the last 22 years, while the demography of SCLC patients at the Moffitt Cancer Center has been consistent yet patient survival has improved.

The multivariable models in the present analysis revealed that older patients, men, current smoking, and ES-SCLC patients were associated with an increased risk of death which is consistent with other studies21,22. Tumor stage is a well-documented prognostic and predictive factor in SCLC6,21. In the current analyses we used a modified two-stage VALG staging system by incorporating treatment and presence of effusion into the local, regional, and distant extent of the disease. This approach allowed us to maximize the sample size by classifying most of the patients into the two-stage VALG staging system and simultaneously accounting for the prognostic effects of treatment, presence of effusion, and extent of the disease. TNM staging data, which has been previously proposed to replace the VALG staging system23, were also available on these patients and we found that the 5-year survival rate increased from 11.8% to 19.3% for stage III patients (P < 0.001) and from 1.0% to 3.0% for stage IV (P < 0.001). There were too few individuals with stage I or II for each time-period to provide accurate 5-year survival rates. Importantly, despite significant differences in stage of disease and treatment across the two time-periods, the final model for the entire cohort of patients revealed a 29% (HR = 1.29; 95% CI 1.11 – 1.49) increased risk of death of patients diagnosed in 1986 to 1999 compared to SCLC patients diagnosed in 2000 to 2008 after adjusting for demographic and clinical factors.

The observed improvements in SCLC survival over the last 22 years is likely attributed to many factors including advances in concurrent chest radiotherapy and chemotherapy24, improvements in chemotherapy regimens6,21, and use of prophylactic cranial irradiation. In our study we observed a significant decrease in patients treated with chemotherapy alone (35.6% to 24.3%) and a subsequent increase in patients treated with multiple modalities. Furthermore, among patients receiving first line chemotherapy, we found a significant increase in the percentage of patients receiving Carboplatin and Etoposide and a decrease in the percentages of patients receiving CAV (22.6% to 0.6%) and Cisplatinum and Etoposide (45.2% to 33.6%). Clinical trials have shown that platinum-based therapies are associated with significantly improved survival rates compared to CAV chemotherapy (reviewed in 25). Thus, the observed temporal shift in our study from first line CAV chemotherapy to the platinum-based doublet regimens likely has attributed to the improved survival in these SCLC patients. Additionally, the shift from Cisplatinum (45.2% to 33.6%) to Carboplatin (29.6% to 57.6%) is likely attributed to the known reduced toxicity and adverse effects associated with Carboplatin. Although we do not have data on prophylactic cranial irradiation (PCI), we did note a temporal increase in cranial radiation therapy. Most notably, there was a substantial increase for radiation therapy to both the lung and brain (26.0% to 45.4%) and a small increase for radiation therapy to the brain only (11.0% to 12.6%). PCI has shown to reduce the incidence of brain metastases and prolong survival outcomes26, thus the observed improved survival could be attributed to the increase of radiation therapy since it is likely that some of these patients received PCI. Other possible explanations for the observed improvement in SCLC survival include better treatment options for patients with poor performance status, routine use of PET scans as part of initial staging, availability of more clinical trials, improved second-line regimens for patients with sensitive disease, and improvements in follow-up and screening for long-term survivors21.

A few limitations must be acknowledged. First, there is a potential lack of generalizability of our study population because the SCLC patients in this analysis were derived from a single Comprehensive Cancer Center and were composed of mostly non-Hispanic Whites. Yet, we must consider that lung cancer patients at a tertiary Cancer Center like the Moffitt Cancer Center could represent more complex cases, and thus our survival rates could be conservative. This is speculation since we do not have demographic and 5-year survival data for regional practices. Also, due to few SCLC patients who are non-White and self-reported Hispanic, the hazard ratios are underpowered to detect a statistically significant point estimates for race and ethnicity. We also acknowledge that our modified stage classification system may misclassify some of the patients which could explain the minimal improvement in 5-year survival among LS disease patients. However, any misclassification would be non-differential across the two time-periods and would not bias the overall finding that SCLC survival has improved over time. Additionally, limited comorbidity data were only available on the 2000 to 2008 time-period which restricted our ability to classify stage IIIB without effusion as LS-SCLC and stage IIIB with effusion as ES-SCLC. However, the prevalence of effusion in the 2000 to 2008 time-period was < 2%, so this limitation likely had any substantial affect on our findings. Another potential limitation is that our analyses were limited to Cancer Registry data, which does not include a detailed and systematic assessment of lung cancer risk factors. The data abstracted by Cancer Registry are limited to information that is available in patient medical records. Nonetheless, such data are power for hypothesis generating, descriptive analyses, and assessments of historical trends in patient characteristics and survival to reveal and successes and where advancements must be made.

5. Conclusion

In summary, this analysis demonstrated important improvements in overall and stage-specific median survival times and survival rates of SCLC patients treated at the Moffitt Cancer Center from 1986 to 2008. LS-SCLC patients have substantially better survival than ES-SCLC patients which emphasizes the need to screen and detect SCLC in its earlier stages resulting in more favorable outcomes5. Unfortunately, various imaging modalities, including screening computed tomography, have been shown to be ineffective for screening for SCLC27,28.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

From 1986 to 2008, small cell lung cancer patient survival significantly improved.

Median survival time and 1-, 2.5- and 5-year survival rates significantly improved.

Multivariable models confirmed the observed improvements in survival.

Advances in treatment and management attributed to the improved survival.

Acknowledgments

The authors also thank Edward T. Chwieseni, the Moffitt Cancer Registry (Director: Karen A. Coyne), and the Research Information Technology (IT) and Data Management and Integration Technology (DMIT) groups.

Funding

This work was supported was by a National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (NIH/NCI) Specialized Program of Research Excellence (SPORE) Grant (P50 CA119997) and an NIH/NCI American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) Grant (5 UC2 CA 148322-02).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Literature Cited

- 1.American Cancer Society . Cancer Facts & Figures 2013. American Cancer Society; Atlanta: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Govindan R, Page N, Morgensztern D, et al. Changing epidemiology of small-cell lung cancer in the United States over the last 30 years: analysis of the surveillance, epidemiologic, and end results database. J Clin Oncol. 2006 Oct 1;24(28):4539–4544. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.4859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riaz SP, Luchtenborg M, Coupland VH, Spicer J, Peake MD, Moller H. Trends in incidence of small cell lung cancer and all lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2012 Mar;75(3):280–284. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elias AD. Small cell lung cancer: state-of-the-art therapy in 1996. Chest. 1997 Oct;112(4 Suppl):251S–258S. doi: 10.1378/chest.112.4_supplement.251s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris K, Khachaturova I, Azab B, et al. Small cell lung cancer doubling time and its effect on clinical presentation: a concise review. Clin Med Insights Oncol. 2012;6:199–203. doi: 10.4137/CMO.S9633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jett JR, Schild SE, Kesler KA, Kalemkerian GP. Treatment of small cell lung cancer: Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013 May;143(5 Suppl):e400S–419S. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalemkerian GP, Akerley W, Bogner P, et al. Small cell lung cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013 Jan 1;11(1):78–98. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Micke P, Faldum A, Metz T, et al. Staging small cell lung cancer: Veterans Administration Lung Study Group versus International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer--what limits limited disease? Lung Cancer. 2002 Sep;37(3):271–276. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(02)00072-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010 Jun;17(6):1471–1474. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0985-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ries LAG. Cancer survival among adults: U.S. SEER program, 1988-2001, patient and tumor characteristics. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demirci E, Daloglu F, Gundogdu C, Calik M, Sipal S, Akgun M. Incidence and clinicopathologic features of primary lung cancer: a North-Eastern Anatolia region study in Turkey (2006-2012) Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14(3):1989–1993. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.3.1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tse LA, Mang OW, Yu IT, Wu F, Au JS, Law SC. Cigarette smoking and changing trends of lung cancer incidence by histological subtype among Chinese male population. Lung Cancer. 2009 Oct;66(1):22–27. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toyoda Y, Nakayama T, Ioka A, Tsukuma H. Trends in lung cancer incidence by histological type in Osaka, Japan. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2008 Aug;38(8):534–539. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyn072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bilaceroglu S, Cimen P, Cirak K, et al. Temporal changes in lung cancer: a 10-year study in a chest hospital. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2008 Dec;69(4):157–163. doi: 10.4081/monaldi.2008.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jemal A, Travis WD, Tarone RE, Travis L, Devesa SS. Lung cancer rates convergence in young men and women in the United States: analysis by birth cohort and histologic type. Int J Cancer. 2003 May 20;105(1):101–107. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li X, Mutanen P, Hemminki K. Gender-specific incidence trends in lung cancer by histological type in Sweden, 1958-1996. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2001 Jun;10(3):227–235. doi: 10.1097/00008469-200106000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spiegelman D, Maurer LH, Ware JH, et al. Prognostic factors in small-cell carcinoma of the lung: an analysis of 1,521 patients. J Clin Oncol. 1989 Mar;7(3):344–354. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1989.7.3.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson BE, Steinberg SM, Phelps R, Edison M, Veach SR, Ihde DC. Female patients with small cell lung cancer live longer than male patients. Am J Med. 1988 Aug;85(2):194–196. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(88)80341-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Albain KS, Crowley JJ, LeBlanc M, Livingston RB. Determinants of improved outcome in small-cell lung cancer: an analysis of the 2,580-patient Southwest Oncology Group data base. J Clin Oncol. 1990 Sep;8(9):1563–1574. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.9.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schabath MB, Thompson ZJ, Gray JE. Temporal trends in demographics and overall survival of non-small-cell lung cancer patients at Moffitt Cancer Center from 1986 to 2008. Cancer Control. 2014 Jan;21(1):51–56. doi: 10.1177/107327481402100107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackman DM, Johnson BE. Small-cell lung cancer. Lancet. 2005 Oct 15-21;366(9494):1385–1396. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67569-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ou SH, Ziogas A, Zell JA. Prognostic factors for survival in extensive stage small cell lung cancer (ED-SCLC): the importance of smoking history, socioeconomic and marital statuses, and ethnicity. J Thorac Oncol. 2009 Jan;4(1):37–43. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31819140fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldstraw P, Crowley J, Chansky K, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: proposals for the revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the TNM Classification of malignant tumours. J Thorac Oncol. 2007 Aug;2(8):706–714. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31812f3c1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pignon JP, Arriagada R, Ihde DC, et al. A meta-analysis of thoracic radiotherapy for small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 1992 Dec 3;327(23):1618–1624. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199212033272302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan BA, Coward JI. Chemotherapy advances in small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Dis. 2013 Oct;5(Suppl 5):S565–S578. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2013.07.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slotman BJ, Faivre-Finn C, Kramer GW, et al. [Prophylactic cranial irradiation in patients with extensive disease caused by small-cell lung cancer responsive to chemotherapy: fewer symptomatic brain metastases and improved survival] Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2008 Apr 26;152(17):1000–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011 Aug 4;365(5):395–409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cuffe S, Moua T, Summerfield R, Roberts H, Jett J, Shepherd FA. Characteristics and outcomes of small cell lung cancer patients diagnosed during two lung cancer computed tomographic screening programs in heavy smokers. J Thorac Oncol. 2011 Apr;6(4):818–822. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31820c2f2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.