Abstract

Summary

The first fifteen consecutive patients treated with multi-field optimization intensity modulated proton therapy (MFO-IMPT) were able to complete treatment with no need for treatment breaks and no hospitalizations. Ten patients presented with SCC and 5 with ACC. There were no treatment-related deaths and with a median follow-up of 28 months, the overall clinical complete response rate was 93.3%. Early clinical outcomes warrant further investigation of proton therapy in the management of head and neck malignancies.

Background

We report the first clinical experience and toxicity of multi-field optimization (MFO) intensity-modulated proton therapy (IMPT) for patients with head and neck tumors.

Methods

Fifteen consecutive patients with head and neck cancer underwent MFO-IMPT with active scanning beam proton therapy. Patients with SCC had comprehensive treatment extending from the base of the skull to the clavicle. The dose for chemoradiation therapy and radiation therapy alone was 70 Gy and 66 Gy, respectively. The robustness of each treatment plan was also analyzed to evaluate sensitivity to uncertainties associated with variations in patient setup and the effect of uncertainties with proton beam range in patients. Proton beam energies during treatment ranged from 72.5 to 221.8 MeV. Spot sizes varied depending on the beam energy and depth of the target, and the scanning nozzle delivered the spot scanning treatment “spot-by-spot” and “layer-by-layer”

Results

Ten patients presented with squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and 5 with adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC). All 15 patients were able to complete treatment with MFO-IMPT with no need for treatment breaks and no hospitalizations. There were no treatment-related deaths and with a median follow-up of 28 months (range: 20-35), the overall clinical complete response rate was 93.3% (95%, confidence interval 68.1% to 99.8%). Xerostomia occurred in all 15 patients as follows; Grade 1 - ten patients, Grade 2 - four patients, and Grade 3 - one patient. Mucositis within the planning target volumes was seen during the treatment of all patients; Grade 1 - one patient, Grade 2 - eight patients, and Grade 3 - six patients. No patient experienced Grade 2 or higher anterior oral mucositis.

Conclusions

This is the first clinical report of MFO-IMPT for head and neck tumors. Early clinical outcomes are encouraging and warrant further investigation of proton therapy in prospective clinical trials.

Introduction

Radiation therapy is a well-established option for the management of head and neck tumors (1). Innovations in the delivery of external beam radiation therapy such as 3-dimensional (3D) conformal radiation and intensity-modulated photon therapy (IMRT) have resulted in greatly improved cure rates and quality of life (2-4). IMRT is the current standard of treatment delivery for head and neck cancer because of its ability to tightly conform the dose to the target volume, thereby sparing normal structures such as the parotid glands. It also accelerates treatment through the use of simultaneous integrated boosts (SIBs) via altered fractionation schedules within the same treatment plan (1). However, optimizing the dose conformality with IMRT often requires the optimization of intensities of multiple coplanar beams, which can result in high doses of radiation to normal tissue structures and subsequent beam-path toxicities to non-target structures (5). The inherent physical properties of proton energy deposition results in virtually no dose being delivered distal to the target (6,7) make proton therapy a logical alternative to IMRT.

Over the last three decades, the most common method of delivering proton beam therapy has been ‘passive scattering’ using compensators, aperatures, and a range-modulation device to create a broad spread-out Bragg peak (SOBP) (8). A compensator is used to create conformal dose only to the distal surface of the target, while an aperture is used to define the lateral extension of the treatment field. While passive scattering is a form of 3D conformal proton beam therapy the dose distributions proximal to the target volume are not conformal in passive scattering. Spot scanning proton therapy (SSPT) does not require compensators or apertures and has recently become available on a new generation of proton therapy delivery systems (9). A proton spot is magnetically scanned lateral to the beam direction to create a large field without introducing scattering elements into the beam path. Mono-energetic spots with different energies from an accelerator are used to create a conformal dose distribution to the entire target volumes. When all spots from all fields are optimized simultaneously using an inverse optimization method, a specific mode of SSPT called multi-field optimization intensity modulated proton therapy (MFO-IMPT) is realized. Similar to IMRT, a simultaneous integrated boost treatment plan can be readily created with MFO-IMPT.

Numerous reports have been published documenting the theoretical advantages of proton therapy over photon therapy for head and neck malignancies (7,10-12). MFO-IMPT has been shown in dosimetric planning studies to be most effective in reducing the doses to the spinal cord, ipsilateral and contralateral parotid glands, and brainstem (13-17). However, to our knowledge, no clinical studies have been conducted to prove or disprove the theoretical advantages of MFO-IMPT over IMRT for patients with head and neck tumors. The purpose of this pilot clinical study was to report our early results with MFO-IMPT for the treatment of head and neck malignancies.

Materials and Methods

Subjects were 15 consecutive patients with head and neck malignancies who were prospectively enrolled on an approved institutional review board prospective protocol and treated with MFO-IMPT with each patients informed written consent. Tumors in all cases were evaluated by central pathologic review, and all cases were evaluated weekly in a multidisciplinary clinic with the participation of surgical, medical, and radiation oncologists specializing in the treatment of head and neck cancer.

Treatment planning and delivery

All patients underwent computed tomography (CT) imaging for treatment planning (i.e., simulation) purposes while supine with a customized thermoplastic mask and bite block for immobilization. Doses were prescribed in grays (Gy) Relative Biological Effectiveness (RBE), assuming RBE of 1.1 for protons. Organs at risk with specified dose contraints were contoured for treatment planning included the brain (maximum (max) dose less than 60 Gy), brainstem (max dose less than 54 Gy), spinal cord (max dose less than 45 Gy), optical apparatus (max dose less than 54 Gy), cornea (max dose less than 35 Gy), cochleas (max dose less than 35 Gy), salivary glands (mean dose less than 26 Gy), oral cavity (mean dose less than 30 Gy), and larynx (mean dose less than 35 Gy). All contours in all cases were reviewed for quality assurance (QA) by a team of head and neck radiation oncology experts. The planning target volumes (PTVs) delineation for IMPT patients were done in similar fashion to our IMRT treated patients. The PTV was defined by adding 3-5 mm to the CTVs while ensuring critical structures were not compromised. Treatment planning was done on an Eclipse proton therapy treatment planning system (version 8.9, Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, CA). Normally three fields from three different beam directions (combing gantry/couch angles) were used for MFO-IMPT head and neck patients. The beam angles for bilateral neck treatment were left and right anterior oblique beams with slight superior-inferior (couch kick 15° to 20°) as well as a single posterior beam. We chose these beams to optimize target coverage while minimizing dose to the brain, brainstem, spinal cord, oral cavity, salivary glands, and larynx. Specifically, the anterior oblique beams place the most distal Bragg peaks lateral to spinal cord; and the posterior beam passes the spinal cord and places the distal Bragg peaks just posterior to the parotid gland. The other important consideration for selecting these beam angles is to minimize the uncertainties along the beam path by avoid beams going through the mouth/teeth from anterior and the shoulders. For paranasal sinus tumors, a vertex beam was incorporated into the treatment planning to minimize the dose to the optic apparatus (i.e. optic nerves, optic chiasm, and corneas, etc.). For ipsilateral neck treatment, two to three ipsilateral beam angles were chose to eliminate dose to the contralateral neck and spare the salivary glands, oral cavity, brainstem, larynx, and optic apparatus, and cochleas. The energy layers required for each field were determined by the water equivalent thickness of the largest target volume in the beam direction. Metal artifacts were managed by contouring regions with HU great than 2500 and assigning the HU value of the material with correct relative linear stopping power. Artifacts in nearby soft tissues were contoured and assigned to the average HU value of the surrounding tissues without artifacts.

The system optimized the weights (intensities) of all spots from all fields simultaneously using a simultaneous spot optimization algorithm with the objective of achieving specified normal tissue and target dose and dose-volume constraints. SIB with accelerated fractionation was prescribed for all patients and achieved by using the MFO-IMPT option in Eclipse. For treatment planning, the goals and constraints were as follows; 95% of the planning target volumes had to be covered with the prescribed doses. For the organs at risk, treatment planning goals include the maximum dose to the spinal cord less than 45 Gy (RBE), the mean dose to the parotid dose less than 26 Gy(RBE), the mean dose to larynx less than 25 Gy(RBE), the mean dose to oral cavity less than 15 Gy(RBE), the maximum dose optic apparatus and brain stem less 54 Gy(RBE), the maximum dose to the brainstem less than 54 Gy(RBE), the maximum dose to the cochlea less than 35 Gy(RBE), and the maximum dose to the cornea less than 35 Gy(RBE).

Radiation Target Volumes and Doses

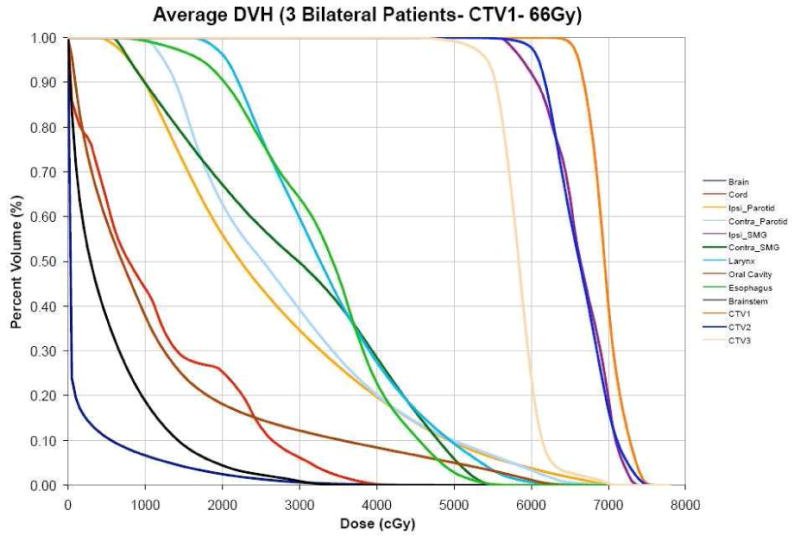

Prescribed doses to the target volumes, and corresponding boost doses depended on whether patients were to receive concurrent chemoradiation therapy or radiation alone. For patients receiving concurrent chemoradiation, the prescribed dose to CTV1 (defined as gross disease plus a 1-cm margin) was 70 Gy(Relative Biological Effectiveness (RBE), assuming RBE of 1.1 for protons) to be given in 33 fractions of 2.12 Gy(RBE) per fraction; dose to the CTV2 (encompassing the high-risk nodal volume adjacent to gross disease in the neck) was 63 Gy(RBE) in 1.9-Gy(RBE) fractions; and dose to CTV3 (encompassing an additional margin beyond CTV2 for patients with pharyngeal tumors and uninvolved nodes in the neck considered to be at risk of harboring subclinical disease) was 57 Gy(RBE) in 1.7-Gy(RBE) fractions. For patients treated with proton therapy alone, the prescribed dose to CTV1 was 66 Gy(RBE) in 30 fractions of 2.2 Gy(RBE) each; to CTV2, 60 Gy(RBE) in 2.0-Gy(RBE) fractions; and to CTV3, 54 Gy(RBE) in 1.8-Gy fractions (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Average DVHs of all three patients with bilateral oropharyngeal tumors treated with IMPT alone to 66 Gy (RBE) in 30 fractions. (Ipsi = ipsilateral, Contra = contralateral, SMG = submandibular gland, CTV = clinical target volume)

The planning target volumes (PTVs) were defined as a 3 mm expansion of the CTVs. Strictly speaking, the PTV concept commonly used in photon therapy cannot be directly used for proton therapy because the range uncertainties are beam-direction-specific (18). However, beam-specific PTVs (bsPTVs) (19) are not available in our clinical treatment planning system for IMPT. Nevertheless, we used the PTV concept to manage delivery uncertainties for plans with a non-parallel-opposed beam arrangements (20).

QA Procedures

Patient-specific QA measurements were based on a recently published method developed for scanning beams (21) with appropriate modifications. The robustness of each treatment plan was also analyzed to evaluate sensitivity to uncertainties associated with variations in patient setup and the effect of uncertainties with proton beam range in patients (22, 23). We evaluated the robustness of the IMPT plans to setup and range uncertainties using a worst-case analysis approach (24). The setup uncertainty for proton therapy of head and neck cancer in our practice is estimated to be 3 mm. The range uncertainty due to stopping power conversion error, computed tomography artifacts, and patient anatomy changes is assumed to be 3.5% of the nominal beam ranges. The perturbations included 6 spatial shifts along the three major axes (left-right, posterior-anterior, and superior-inferior), 2 range shifts – a total of 8 perturbed dose distributions. Dose distributions were recalculated in Eclipse for each of the above described 8 perturbed situations. We extracted the highest and the lowest dose values in each voxel from the nominal and the 8 perturbed dose distributions, forming a hot dose distribution with the highest values and a cold dose distribution with the lowest values. The dose distributions derived in this way provided an estimate of the robustness of the delivered dose to spatial and range uncertainties. Proton beam energies during treatment ranged from 72.5 to 221.8 MeV. Spot sizes varied depending on the beam energy and depth of the target, and the scanning nozzle delivered the spot scanning treatment “spot-by-spot” and “layer-by-layer” (25,26). The spot sizes ranges from sigma = 0.5 to 1.4 cm in air at the isocenter. The switch time between layers is 2.1 seconds.

Patients were scanned weekly with verification CT scans to evaluate the set-up, range, and anatomical uncertainties that would necessitate adaptive replanning. Adaptive replanning due to weight loss occurred during the fourth week of treatment. Daily image guidance was performed using orthogonal 2D kV x-ray images and comparing with DRRs generated by the treatment planning system (TPS) from simulation CT images to align the patient.

Toxicities and Clinical Response

Acute toxicities were assessed weekly during the proton treatment by the treating physician and were documented according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v4.0. Clinical response was assessed at 6-10 weeks after treatment completion by physical, endoscopic, and radiographic examination.

Statistical Considerations

Descriptive statistics are used to summarize toxicity and tumor response data. Exact binomial confidence interval estimates are provided for the MFO-IMPT completion rate and the clinical complete response rate. Analyses were performed with StatXact-9© for Windows (Copyright © 2010, 1989-2010, Cytel Software Corporation, Cambridge, MA).

Results

Patient and treatment characteristics are listed in Table 1. Ten patients presented with squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and 5 with adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC). The primary SCC tumors were located in the oropharynx (8), nasopharynx (1), and unknown with cervical metastases (1). Of the 8 oropharyngeal tumors, 7 were both p16- and human papillomavirus (HPV)-positive, and the eighth was both p16- and HPV-negative. The ACCs were located in the nasopharynx (3) or paranasal sinuses (2). Disease in the latter 2 cases was recurrent after surgery and postoperative radiation. All 5 patients with ACC were treated with concurrent chemotherapy and MFO-IMPT for unresectable disease. Five patients (all with SCC) underwent taxane and platinum–based induction chemotherapy before MFO-IMPT. Twelve patients (including all 5 with ACC) had MFO-IMPT with concurrent chemotherapy consisting of either cisplatin (7 patients), carboplatin (4 patients), or cetuximab (1 patient).

Table 1. Patient and treatment characteristics.

| Toxicity and Grade | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anterior | |||||||||||

| Patient | Tumor Site | Histology | T/N/M Classification | Treatment | Dysgeusia | Radiation Dermatitis | Oral Mucositis | Nausea | Vomiting | Weight Loss | Response |

| 1 [66 yo M] | BOT | SCC | T4N3M0 | Induction TPF → CRT (carboplatin) | 2 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | CR |

| 2 [67 yo M] | BOT | SCC | T2N1M0 | CRT (cetuximab) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | CR |

| 3 [58 yo M] | Tonsil | SCC | T2N2bM0 | Induction carbo+pacl →CRT (cisplatin) | 2 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2 | CR |

| 4 [38 yo F] | Tonsil | SCC | T2N2bM0 | Ind CT [TPF] → CRT (cisplatin) | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | CR |

| 5 [59 yo M] | Tonsil | SCC | T3N1M0 | CRT (cisplatin) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3 | CR |

| 6 [61 yo M] | Tonsil | SCC | T2N2bM0 | Induction PCC →CRT (carboplatin) | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | CR |

| 7 [48 yo M] | Tonsil | SCC | T1N1M0 | RT | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | CR |

| 8 [63 yo M] | Tonsil | SCC | T2N2bM0 | S →RT | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | CR |

| 9 [54 yo M] | Unknown | SCC | T0N1M0 | RT | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | CR |

| 10 [28 yo M] | NPX | SCC | T1N1M0 | Induction TPF →CRT (carboplatin) | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | CR |

| 11 [33 yo F] | NPX | ACC | T4N0M0 | CRT (cisplatin) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | CR |

| 12 [47 yo F] | NPX | ACC | T2N0M0 | CRT (cisplatin) | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | CR |

| 13 [32 yo F] | NPX | ACC | T4N0M0 | CRT (ciplatin) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | PR |

| 14 [37 yo F] | PNS | ACC | Recurrent | S →CRT (cisplatin) | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | CR |

| 15 [48 yo M] | PNS | ACC | Recurrent | S →CRT (carboplatin) | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 | CR |

Abbreviations: BOT, base of tongue; NPX, nasopharnyx; PNS, paranasal sinus; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; ACC, adenocarcinoma; CRT, concurrent chemotherapy; TPF, docetaxel, cisplatin, fluorouracil; PCC, paclitaxel, cisplatin, and cyclophosphamide; S, surgery; RT, intensity modulated proton-beam therapy; CR, complete response; PR, partial response.

All 10 patients with SCC had comprehensive treatment extending from the base of the skull to the clavicle to encompass both the primary tumor and neck regions. All 5 patients with ACC received 70 Gy(RBE) in 33 fractions to gross disease with margin (CTV1) but no treatment to the regional lymphatics. All 15 patients were able to complete treatment with MFO-IMPT (100% completion rate with 95% CI 78.2% to 100%) without treatment breaks.

Toxicity

There were no treatment-related deaths (i.e., grade 5 toxicities) and no patient required hospitalization. Doses to the organs at risk for proton therapy confined to the base of skull are shown in Table 2; those for treatment that included the regional lymphatics are shown in Table 3. Xerostomia occurred in all 15 patients as follows; Grade 1 – ten patients, Grade 2 – four patients, and Grade 3 – one patient. Mucositis within the planning target volumes was seen during the treatment of all patients; Grade 1 – one patient, Grade 2 – eight patients, and Grade 3 – six patients. No patient experienced Grade 2 or higher anterior oral mucositis.

Table 2. Doses to critical organ structures associated with regional lymphatic treatment of pharyngeal squamous cell tumors.

| Radiation Dose to Organs at Risk, in Gy(RBE) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | Brain-stem (max) | Spinal Cord (max) | Right Parotid (mean) | Left Parotid (mean) | Left Sub-mandibular (mean) | Right Sub-mandibular (mean) | Anterior Oral Cavity (mean) | Larynx (mean) | Esophagus (max) |

| 1 | 36.0 | 46.3 | 70.3 | 28.8 | 24.1 | 71.9 | 7.0 | 31.3 | 55.6 |

| 2 | 35.5 | 42.3 | 27.1 | 25.6 | 43.5 | 68.2 | 25.1 | 36.1 | 41.6 |

| 3 | 47.3 | 39.6 | 24.1 | 34.8 | 71.9 | 53.4 | 20.2 | 30.1 | 44.9 |

| 4 | 20.8 | 17.7 | 20.2 | 40.1 | 66.8 | 17.2 | 5.6 | 31.4 | 56.1 |

| 5 | 42.1 | 39.2 | 20.2 | 34.7 | 71.9 | 25.4 | 10.6 | 36.0 | 59.1 |

| 6 | 26.1 | 30.3 | 2.7 | 38.5 | 70.2 | 44.4 | 18.7 | 36.5 | 62.6 |

| 7 | 47.7 | 39.6 | 0.0 | 50.3 | 66.5 | 0.2 | 3.3 | 22.1 | 54.6 |

| 8 | 51.0 | 39.0 | 26.1 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 67.1 | 5.2 | 1.04 | 49.6 |

| 9 | 24.1 | 28.5 | 31.8 | 19.7 | 26.8 | 63.7 | 6.0 | 35.1 | 50.9 |

| 10 | 50.1 | 36.4 | 20.0 | 41.1 | 66.2 | n/a | 9.8 | 27.8 | 44.3 |

Table 3. Doses to critical organ structures associated with base-of-skull treatment of recurrent paranasal sinus tumors and adenoid cystic carcinoma of the nasopharynx.

| Radiation Dose to Organs at Risk, in Gy(RBE) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | Brain- stem (max) | Spinal Cord (max) | Right Optic Nerve (max) | Left Optic Nerve (max) | Optic Chiasm (max) | Right Cochlea (mean) | Left Cochlea (mean) | Right Parotid (mean) | Left Parotid (mean) |

| 11 | 54.4 | 45.8 | 47.5 | 48.5 | 55.0 | 19.8 | 35.5 | 18.6 | 46.2 |

| 12 | 56.7 | 40.6 | 25.0 | 23.3 | 34.3 | 62.0 | 63.1 | 24.3 | 24.4 |

| 13 | 59.0 | 38.3 | 48.4 | 29.8 | 54.2 | 72.3 | 33.8 | 24.4 | 8.6 |

| 14 | 22.8 | 7.3 | 51.7 | 50.4 | 51.2 | 30.6 | 15.2 | 34.0 | 21.5 |

| 15 | 18.6 | 5.8 | 0.0 | 24.6 | 38.6 | 64.4 | 7.1 | 14.9 | 9.6 |

Six patients (2 with base-of-tongue tumors, 2 tonsil, 1 nasopharyngeal, and 1 paranasal sinus) experienced no nausea or vomiting during the course of treatment despite five of those patients having had concurrent chemoradiation. Two patients experienced vomiting (1 grade 3 and 1 grade 4; both required feeding tubes for grade 3 dysphagia and experienced grade 2 or 3 weight loss during treatment). Five patients (38%) experienced grade 3 dysphagia. Dysgeusia was common, with 12 patients (80%) experiencing grade 2 effects such as altered taste with change in diet, noxious or unpleasant taste, or loss of taste. Weight loss during treatment to the oropharynx and nasopharynx ranged from 1.7% (2.2 kg) to 21.1% (19 kg).

No patient experienced grade 4 or 5 radiation dermatitis. Two of the 3 patients with ACC of the nasopharynx experienced faint erythema (grade 1), and the third patient experienced no skin changes. At the initial follow-up at 6 weeks after treatment, all dermatitis had resolved to grade 0 or grade 1. Two patients had MFO-IMPT concurrent with cisplatin after salvage surgery for recurrent paranasal sinus tumors. Both patients experienced dysphagia, dysgeusia, and radiation dermatitis, but neither experienced anterior oral mucositis or vomiting and there were no grade 4 or 5 toxicities. At 2 years, 10 patients experience Grade 1 xerostomia consisting of dryness without significant dietary alteration. Three of the 10 patients experienced Grade 1 dysguesia consisting of altered taste but no change in diet.

Response

With a median follow-up of 28 months (range: 20-35), all 10 patients with SCC and 4 of the 5 patients with ACC experienced a clinical complete response (CR); one patient with ACC, who was being reirradiated for a recurrent paranasal sinus tumor, had a partial response. The overall clinical complete response rate is 93.3% (95% CI 68.1% to 99.8%). Figures 2 and 3 illustrate the complete clinical responses of our first cases of patients treated with MFO-IMPT for nasopharyngeal ACC and oropharyngeal SCC, respectively.

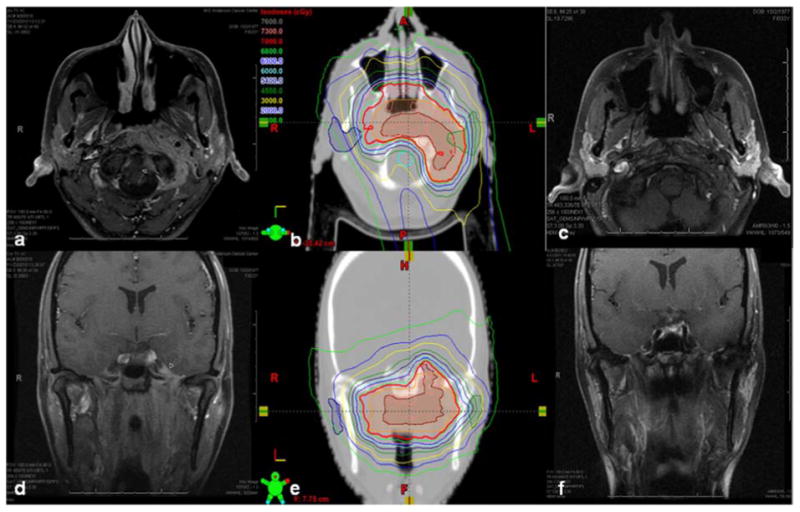

Figure 2.

Unresectable T4N0M0 adenoid cystic carcinoma of the nasopharynx in a 33-year-old woman. Panels a and d, CT scans showing tumor invasion the carotid space, extending circumferentially around the lateral aspect of C1 with epidural extension and perineural spread into the left hypoglossal canal, left vidian canal, left foramen rotundrum, and left foramen ovale. The tumor also extended into the left middle cranial fossa and encased the left internal carotid artery up to the petrous carotid canal. Panels b and e, isodose lines of the MFO IMPT treatment plan in the axial (b) and coronal (e) planes (gross disease is contoured in maroon). Panels c and f, CT scans obtained at 6 weeks after concurrent chemoradiation therapy to 70 Gy(RBE) in 33 fractions with cisplatin illustrate a clinical and radiographic complete response. The patient remains without evidence of disease three years from treatment.

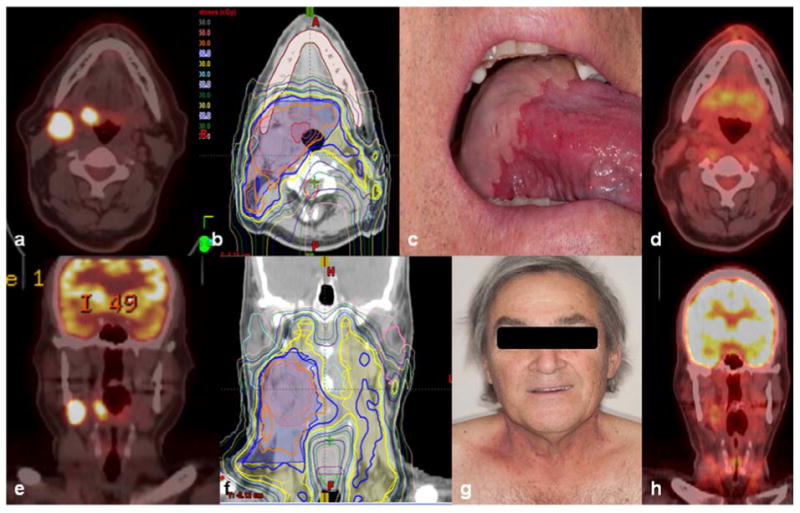

Figure 3.

T2N2b human papillomavirus–positive squamous cell carcinoma of the right tongue base in a 67-year-old man. Panels a and e, PET/CT scans show avid primary tumor and cervical node metastases. Panels b and f, isodose lines of the MFO IMPT treatment plan in the axial (b) and coronal (f) planes. Panels c and g, confluent mucositis at the tongue base with no mucositis at the anterior local tongue (c) and grade 2 radiation dermatitis on the neck (g) after receipt of 66 Gy(RBE) with concurrent cetuximab illustrate treatment reactions consistent with the treatment plan. Panels d and h, PET/CT scans obtained at 10 weeks after treatment illustrate complete clinical, metabolic, and radiographic. The patient remains without evidence of disease two and a half years from treatment.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first report of IMPT using MFO for head and neck malignancies. We used MFO-IMPT, applied with a discrete spot scanning proton beam, from the base of the skull to the clavicles safely, with no grade 5 toxicities and only 1 episode of grade 4 toxicity (vomiting). We further demonstrated the successful use of accelerated altered fractionation by incorporating SIB with proton therapy. Oropharygeal tumors, nasopharygeal tumors, and tumors metastatic to the neck were all treated successfully after induction chemotherapy and concurrent chemotherapy regimens without the need for treatment breaks, chemotherapy dose reduction, or hospitalization. MFO-IMPT was also successful in treating recurrent paranasal sinus malignancies. Clinical and radiographic responses provide further evidence of the safety and effectiveness of MFO-IMPT for this purpose.

MFO-IMPT plans usually use two to three beams while IMRT plans often use nine beams so the dose proximally to the Bragg peak may be a modest improvement over IMRT. The total treatment time for two field plans was 20.1 min (SD 3.4) with beam delivery time of 3.6 min (SD 1.5). The total treatment time for three fields was 32.4 min (SD 5.6 min) with beam delivery time of 9.4 min (SD 2.6 min). Although this study demonstrates early clinical applications of MFO-IMPT, several proton treatment-related uncertainties that can affect the robustness of the treatment plan require further investigation. These uncertainties result from variations in the range of the proton beam, daily set-up, intrafraction patient motion, anatomical changes and weight loss during the treatment course. The MFO-IMPT fields individually produced highly non-uniform dose distributions which combine to produce the desired apparently uniform dose. Such dose distributions are highly sensitive to the uncertainties mentioned above and carry a risk of both underdosing or overdosing target volumes and/or normal structures. To minimize many of these uncertainties and their effect, advanced immobilization techniques, image guidance, optimal beam angle selection, robust analysis, robust optimization, and adaptive planning are all being actively investigated (27-29). With MFO-IMPT, image guidance should be performed daily with either daily KV imaging and periodic CT verification scans or in-room CT-based volumetric imaging. In the current study, most patients experienced some weight loss during treatment, but only 2 required feeding tubes. In IMRT, weight loss or tumor volume reduction may require remasking and replanning during treatment; however, anatomical changes may have a greater impact on the MFO-IMPT dose distributions. In addition to accounting for the effect of weight loss, nutritional interventions should be considered to maintain body mass to the greatest extent possible during treatment while also seeking to balance oral nutrition and hydration so as to maintain swallowing functionality. Finally, cost-effectiveness of IMPT over IMRT for head and neck patients must be considered in the emerging health care environment as recent modeling suggests that IMRT may be more cost-effective than IMPT (30).

In conclusion, this is the first clinical report of MFO-IMPT in the management of head and neck cancers. Our early clinical results are positive and warrant further investigation of MFO-IMPT in the treatment of head and neck malignancies. We will continue to follow these patients and others on this protocol and report their clinical outcomes with longer-term follow-up. Future prospective trials will determine if MFO-IMPT is able to reduce beam-path toxicities and translate into an improvement in the therapeutic ratio, with superior disease outcomes and a reduction in treatment-related morbidity.

Acknowledgments

Christine Wogan, MS, ELS. for editing of the manuscript and Khadijeh Rezaei, MD for data management. This study was supported by P01CA021239 from the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no actual or potential conflicts of interest

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Anonymous. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. [Accessed January 22, 2012]; Available at: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp.

- 2.Eisbruch A, Harris J, Garden AS, et al. Multi-institutional trial of accelerated hypofractionated intensity-modulated radiation therapy for early-stage oropharyngeal cancer (RTOG 00-22) Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76:1333–1338. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chao KS, Deasy JO, Markman J, et al. A prospective study of salivary function sparing in patients with head-and-neck cancers receiving intensity-modulated or three-dimensional radiation therapy: initial results. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;49:907–916. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)01441-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dirix P, Vanstraelen B, Jorissen M, Vander Poorten V, Nuyts S. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy for sinonasal cancer: improved outcome compared to conventional radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;78:998–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.09.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenthal DI, Chambers MS, Fuller CD, et al. Beam path toxicities to non-target structures during intensity-modulated radiation therapy for head and neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;72:747–755. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Purdy JA. Dose to normal tissues outside the radiation therapy patient's treated volume: a review of different radiation therapy techniques. Health Phys. 2008;95:666–676. doi: 10.1097/01.HP.0000326342.47348.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lomax AJ, Goitein M, Adams J. Intensity modulation in radiotherapy: photons versus protons in the paranasal sinus. Radiother Oncol. 2003;66:11–18. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(02)00308-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sahoo N, Zhu XR, Arjomandy B, et al. A procedure for calculation of monitor units for passively scattered proton radiotherapy beams. Med Phys. 2008;35:5089–5097. doi: 10.1118/1.2992055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu XR, Poenisch F, Song X, et al. Patient-specific quality assurance for prostate cancer patients receiving spot scanning proton therapy using single-field uniform dose. Int J Rad Onc Biol Phys. 2011;81:552–559. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.11.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stenekar M, A, Schneider U. Intensity Modulated photon and proton therapy for the treatment of head and neck tumors. Radiother Oncol. 2006;80:263–267. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2006.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palm A, Johansson KA. A review of the impact of photon and proton external beam radiotherapy treatment modalities on the dose distribution in field and out-of-field; implications for the long-term morbidity of cancer survivors. Acta Oncol. 2007;46:462–473. doi: 10.1080/02841860701218626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van de Water TA, Bijl HP, Schilstra C, Pijls-Johannesma M, Langendijk JA. The potential benefit of radiotherapy with protons in head and neck cancer with respect to normal tissue sparing: a systematic review of literature. Oncologist. 2011;16:366–377. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cozzi L, Fogliata A, Lomax A, Bolsi A. A treatment planning comparison of 3D conformal therapy, intensity modulated photon therapy and proton therapy for treatment of advanced head and neck tumours. Radiother Oncol. 2001;61:287–297. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(01)00403-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kandula S, Zhu X, Garden AS, et al. Spot-scanning beam proton therapy vs intensity-modulated radiation therapy for ipsilateral head and neck malignancies: A treatment planning comparison. Medical Dosimetry. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.meddos.2013.05.001. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mock U, Georg D, Bogner J, Auberger T, Pötter R. Treatment planning comparison of conventional, 3D conformal, and intensity-modulated photon (IMRT) and proton therapy for paranasal sinus carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;58:147–154. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)01452-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Widesott L, Pierelli A, Fiorino C, et al. Intensity-modulated proton therapy versus helical tomotherapy in nasopharynx cancer: planning comparison and NTCP evaluation. Int. J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;72:589–596. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simone CB, 2nd, Ly D, Dan TD, et al. Comparison of intensity-modulated radiotherapy, adaptive radiotherapy, proton radiotherapy, and adaptive proton radiotherapy for treatment of locally advanced head and neck cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2011;101:376–82. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu W, Zhang X, Li Y, et al. Robust optimization of intensity modulated proton therapy. Med Phys. 2012;39:1079–91. doi: 10.1118/1.3679340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park PC, Zhu XR, Lee AK, et al. A beam-specific planning target volume (ptv) design for proton therapy to account for setup and range uncertainties. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lomax AJ. Intensity modulated proton therapy and its sensitivity to treatment uncertainties 1: The potential effects of calculational uncertainties. Physics in medicine and biology. 2008;53:1027–1042. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/53/4/014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu XR, Poenisch F, Song X, et al. Patient-specific quality assurance for prostate cancer patients receiving spot scanning proton therapy using single-field uniform dose. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81:552–559. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.11.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lomax AJ, Pedroni E, Rutz H, Goitein G. The clinical potential of intensity modulated proton therapy. Z Med Phys. 2004;14:147–152. doi: 10.1078/0939-3889-00217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moyers MF, Miller DW, Bush DA, Slater JD. Methodologies and tools for proton beam design for lung tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;49:1429–1438. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)01555-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quan M, Liu W, Wu R, et al. Treatment planning for spot-scanning proton therapy of head and neck cancer: multi-field or single-field optimization? Med Phys. 2013;40(8):081709. doi: 10.1118/1.4813900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith A, Gillin M, Bues M, et al. The M. D. Anderson proton therapy system. Med Phys. 2009;36:4068. doi: 10.1118/1.3187229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gillin MT, Sahoo N, Bues M, et al. Med Phys. Vol. 37. Anderson Cancer Center, Proton Therapy Center; Houston: 2010. Commissioning of the discrete spot scanning proton beam delivery system at the University of Texas M.D. pp. 154–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu W, Frank SJ, Li X, et al. PTV-based IMPT optimization incorporating planning risk volumes vs. robust optimization. Med Phys. 2013 Feb;40(2):021709. doi: 10.1118/1.4774363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu W, Frank SJ, Li X, et al. Effectiveness of Robust Optimization in Intensity-Modulated Proton Therapy Planning for Head and Neck Cancers. Med Phys. 2013 May;40(5):051711. doi: 10.1118/1.4801899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cao W, Lim GJ, Lee A, et al. Uncertainty incorporated beam angle optimization for IMPT treatment planning. Med Phys. 2012 Aug;39(8):5248–56. doi: 10.1118/1.4737870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramaekers B, Grutters J, P, Piils-Johannesma M, et al. Protons in Head and Neck Cancer: Bridging the Gap of Evidence. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;85:1282–1288. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]