Abstract

Purpose of review

To present recent advances in treatment of facial paralysis, emphasizing emerging technologies. This review will summarize the current state of the art in the management of facial paralysis and discuss advances in nerve regeneration, facial reanimation, and use of novel biomaterials. The review includes surgical innovations in re-innervation and reanimation as well as progress with bioelectrical interfaces.

Recent Findings

The past decade has witnessed major advances in understanding of nerve injury and approaches for management. Key innovations include strategies to accelerate nerve regeneration, provide tissue-engineered constructs that may replace nonfunctional nerves, approaches to influence axonal guidance, limiting of donor-site morbidity, and optimization of functional outcomes. Approaches to muscle transfer continue to evolve, and new technologies allow for electrical nerve stimulation and use of artificial tissues.

Summary

The fields of biomedical engineering and facial reanimation increasingly intersect, with innovative surgical approaches complementing a growing array of tissue engineering tools. The goal of treatment remains the predictable restoration of natural facial movement, with acceptable morbidity and long-term stability. Advances in bioelectrical interfaces and nanotechnology hold promise for widening the window for successful treatment intervention and for restoring both lost neural inputs and muscle function.

Keywords: nerve regeneration, tissue engineering, facial nerve paralysis, muscle reinnervation, neuromuscular prosthetic interface

INTRODUCTION

Loss of facial nerve function profoundly alters an individual’s self-image and ability to communicate and express emotion[1]. It also threatens vision due to loss of blink reflex and hampers ability to perform many routine activities such as eating and drinking. Restoring facial movement there fore has far-reaching implications for patients’ quality of life. Identifying a suitable approach to treatment includes a comprehensive assessment of the etiology, severity, and overall context of the paralysis. The duration of paralysis, integrity of neuromuscular structures, and a variety of biopsychosocial factors all come into play. Recent years have witnessed major advances in treatment of facial paralysis, but existing treatments continue to be limited by donor site morbidity, invasiveness of the surgery, and difficulty in achieving normal mimetic function and reproducible outcomes[2].

This review focuses on surgical advances and emerging technologies that hold most promise for advancing the field of facial paralysis. This article is organized in 3 sections, each of which draws on pioneering research conducted in biomedical engineering laboratories or research in the operating room motivated by a desire to improve outcomes. We initially discuss progress in the areas of nerve regeneration and the use of novel biomaterials. We then cover new findings in facial nerve reinnervation and facial reanimation. The final section on bioelectrical interfaces and tissue engineering summarizes advances on the horizon in this rapidly evolving field.

ADVANCES IN NERVE REGENERATION

In this section we trace how discoveries in translational research laboratories are leading to innovative clinical treatments for facial paralysis. This work includes data on nerve transection repair and nerve gap injuries, as well as use of clinically available glues and nerve conduits. We also consider differences between motor versus sensory nerve grafts and strategies to enhance nerve regeneration. Recent findings in motor neuron regeneration and axonal guidance also have implications for nerve reconstruction and timing of radiation therapy.

Nerve repair and conduits

Fibrin glue and nerve conduits have a growing role in nerve repair. Animal studies demonstrate less inflammation and increased axonal regeneration with the use of fibrin glue compared to suture, although functional benefits have not been confirmed[3]. When a large nerve defect is present, surgeons routinely use donor autographs, such as sural nerve or medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve. Nerve fibers will not spontaneously regenerate across a gap greater than three to four centimeters, however. Collagen tubes and an a cellular cadaveric nerve allograft, such as Avance (Axo-Gen), are off-the-shelf products that may support nerve regeneration for up to three centimeters [1, 4]. Polyglycolic acid conduits are another alternative to standard repair techniques for short (< 8 mm) nerve gap repairs [5]. Neural tissue engineering with conducting polymers [6], cross-linked collagen fibers [7], and cultured Schwann cells [8]show promising results for repair of critically sized nerve defects. Biodegradeable polymer nerve conduits can be enriched with growth factors [1], and newly developed 3D bifurcating microchannel scaffolds allow for separation of regenerating neurites into axonal bundles [9].

Motor versus sensory schwann cells

Animal studies afford insight into requirements for successful motoneuron regeneration, causes of synkinesis, and optimal methods for nerve stump coaptation [10, 11]. Of special interest are Schwann cells, neural supporting cells that myelinate axons, provide trophic support, and influence nerve regeneration[12]. After nerve injury, Schwann cells proliferate and organize themselves to help guide regenerating axons to their distal targets [13]. Gene expression and phenotype studies of Schwann cells suggest differences between Schwann cells from sensory versus motor nerves [14]. Schwann cells dedifferentiate to a permissive state of growth after nerve injury, whereas adult Schwann cells lack the growth permissive phenotype [10]. Animal studies have also shown improved motoneuron regeneration with motor grafts versus sensory grafts [15].

This finding may have important clinical implication, since surgeons routinely use sensory nerves to bridge motor nerve defects, despite availability of dispensable motor nerves. This area awaits clinical studies reporting on histological, physiological, and functional outcomes after motor versus sensory nerve grafting. Based on available translational studies, however, the corresponding author favors use of dispensable motor nerves for reconstruction of motor defects. For example, the motor nerve to the vastus lateralis muscle is readily accessible when performing an anterolateral thigh free flap. It is branching nerve that is well-suited to facial nerve reconstruction and cable grafting. There are typically 4 or 5 branches that arborize, with variable relation to the descending branch of the lateral circumflex femoral artery and its perforators. With respect to nerve orientation, retrograde placement of nerve grafts is commonly performed in experimental models to avoid loss of nerve fibers that would otherwise exit the graft via collateral branches before reaching the distal side. In clinical practice, retrograde placement is advisable with individual cable grafts, whereas anterograde placement with preservation of branching pattern is appropriate for defects where the graft must bridge between a sectioned nerve trunk and 2 or more distal branches. The medial antebrachial cutaneous (MABC) nerve, although sensory, has a favorable branching pattern for this situation. The MABC is useful for reconstruction after skull base cancer resection, whereuse of the greater auricular nerve is often avoided due to risk of malignant involvement.

Motoneuron Regeneration and Radiation

A variety of recent developments have emerged pertaining to axonal guidance and radiation planning. There has been longstanding controversy regarding whether motor nerves exhibit spontaneous collateral sprouting after end-to-side nerve repair. Animal studies demonstrate that motor neuron regeneration through end-to-side repairs (as is done in faciohypoglossal nerve transfer) is a function of donor nerve axotomy, indicating that division of nerve fibers is a necessary step for successful clinical reconstruction. The effect of external beam radiation and brachytherapy on nerve regeneration has also recently been studied. Hontanilla et al. [16]reports that recovery of facial nerve function after tumor removal and immediate nerve repair was not impaired by radiation, lending credence to prior similar findings in animal models.

SURGICAL INNOVATIONS IN REINNERVATION & REANIMATION

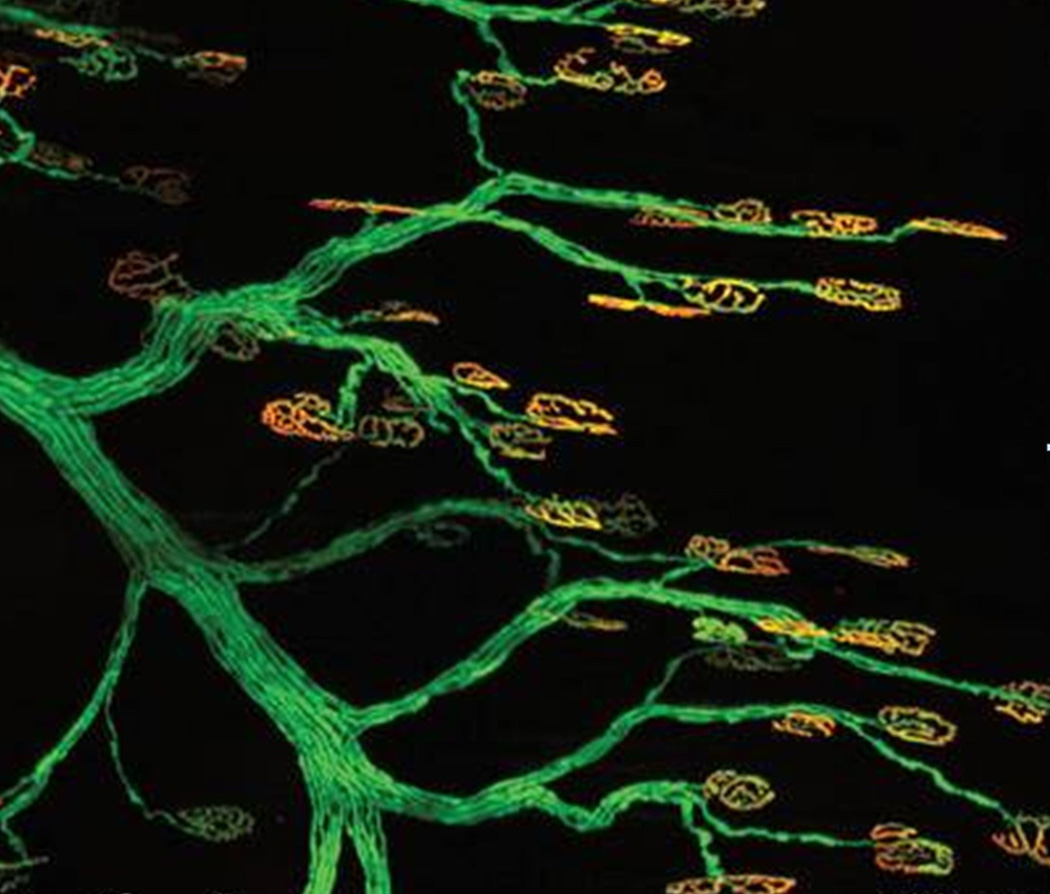

Restoring dynamic, symmetrical facial movement requires providing an appropriate neural input to a muscle capable of producing tone and facial expression. This neural input may come from the facial nerve (ipsilateral or contralateral). An alternative nerve source, or nerve substitution, is needed if a proximal facial nerve stump is unavailable. Nerve substitutions involve using donor nerves, such as the hypoglossal nerve or the motor branch of the trigeminal nerve (masseteric nerve), to provide neural input to the distally affected facial nerve[17]. The muscle may be facial musculature, muscle from a regional source (temporalis muscle), or muscle transferred from a distant site (e.g. gracilis free muscle transfer). Intact neuromuscular junctions (FIGURE 1) are critical for successful muscle reinnervation[18]. If facial musculature has suffered prolonged denervation, loss of motor endplates and denervation atrophy will degrade reinnervation efficacy, and reanimation with an alternative muscle source is needed.

FIGURE 1.

Preservation of motor endplates at the neuromuscular junction is required for successful reinnervation after nerve injury. Confocal imaging shows motor endplates (orange; Alexa 594-bungarotoxin) innervated by terminal axons (green; fluorescent protein), adapted with permission from Magill CD et al [18].

Hypoglossal versus Masseteric Nerve Inputs

The roles for hypoglossal and masseteric nerve in treatment of facial paralysis are evolving. Hypoglossal-facial anastomosis, hypoglossal jump graft, and hemi-hypoglossal transfer are well established in facial paralysis, reliably achieving a House-Brackmann III, with improved speech/swallowing and limited lingual morbidity [19]. The masseteric nerve has become a popular choice for ipsilateral nerve transposition due to similar diameter to the facial nerve, favorable location, and low morbidity[20]. In comparing the two nerves, the intrinsic tonic versus dynamic function of each affects facial reanimation; the masseteric nerve affords better excursion and less mass movement, whereas the hypoglossal nerve provides better tone. The masseteric nerve may also provide faster and more symmetrical onset of movement[21]. However, if coaptation to the facial nerve fails with the masseteric nerve, the opportunity to perform future one-stage free gracilis muscle transfers is compromised.

Free muscle transfer

In healthy patients with Möbius syndrome or chronic facial denervation with irreversible muscle atrophy, free muscle transfer has emerged as the preferred approach for reconstruction [17, 22]. Gracilis free muscle transfer achieves quantifiable improvements in static/dynamic symmetry, smile, and angle excursion[23]. Manktelow et al reported on cerebral adaption in adults after free muscle transfer innervated by the masseter motor nerve [24]. Movement-associated cortical reorganization has been best studied in the setting of head trauma, where behavioral changes induce adaptation of neural networks via sprouting, new synapse formation, and restructuring of existing neural pathways. Similar mechanisms may allow for spontaneous smiles after free muscle transfer. Objective clinical staging of cortical adaptation is particularly valuable after masseter-innervated facial reanimation, since the proximity of the brain centers responsible for jaw muscle movement and facial movement limits utility of fMRI.

Tzou et al [25]proposed a 5-step staging system (Chuang Cortical Adaptation Staging System)to gauge cortical adaption after functional free-muscle transplantation. The scale assigns a score from I to V that reflects the status of patients’ coordination and activation of the free muscle graft. Most patients progress through these stages over time, with their staging at key time points guiding decisions for introduction of are habilitation program. Stage I corresponds to no movement or smile; Stage II is a dependent smile; Stage III is an independent smile; Stage IV is spontaneous smile with presence of involuntary movement; and Stage V is a spontaneous smile without involuntary movement. The model can be applied to cross-facial nerve grafting, masseter-innervated muscle, and XI-innervated muscle for facial paralysis. In 360 evaluations of patients with XI-innervated muscle, the intra-class correlation coefficients for inter-rater and intra-rater reliability were 0.929. The authors have used this staging system over a period of 25 years and find that it provides a simple and accurate method to assess facial reanimation.

The gracilis muscle is the preferred option for free muscle transfers, but limitations include aesthetic deformity, poor contraction ratios, and short recipient nerve. To address these concerns Alam et al2]proposed using the sternohyoid for free flap reanimation. The sternohyoid has a reliable, nonessential vascular and neural input, a muscle composition comparable to the zygomaticus major in ratio of type 1:2 fibers, and less muscle bulk than the gracilis. The noncritical function of the muscle, rigid fixation options, and longer recipient nerve are all highly conducive to free tissue transfer. Use of the sternohyoid muscle may also provide better surgical and clinical outcomes due to similarities in muscle structure and purpose, and it has the potential to allow a single-stage cross facial neurorrhaphy.

BIO-ELECTRICAL INTERFACES & EMERGING TECHNOLOGIES

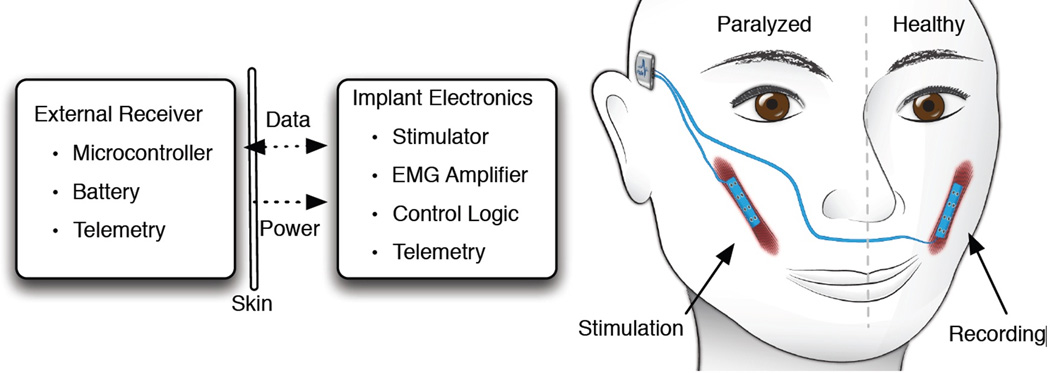

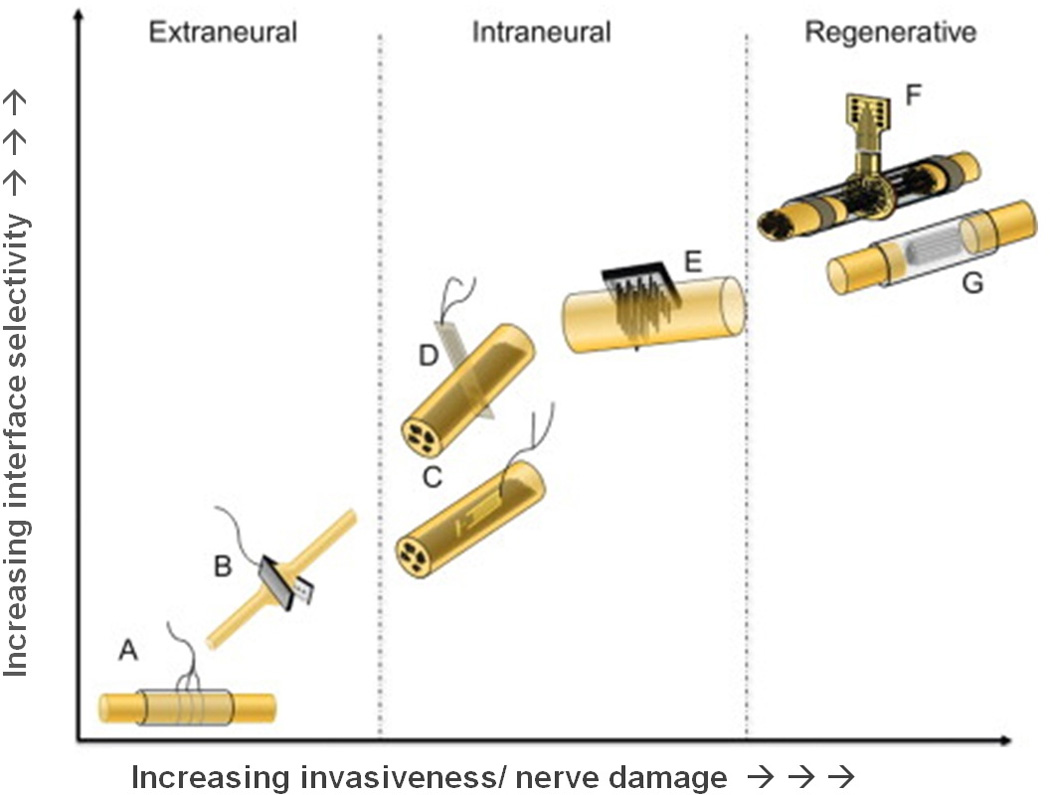

Many proposed strategies for restoring function in facial paralysis patients require a direct neural interface. One application of the interface is to record from intact neural tissue. For example, in a patient with unilateral paralysis or synkinesis, one could extract intricate neural signals from the normal side for treatment of the contralateral impairment. The second application involves electrically stimulating interfaced nerves for functional restoration. In this case, the interface is used to modify the activity of the nerve, thereby inducing muscle contraction to restore movement. An example of an approach that involves recording from the normal face and stimulation of the contralateral face is shown in FIGURE 2 [26]. Multiple potential neural interface technologies are outlined below. Several of these interfaces are shown in FIGURE 3 27]. With any of these technologies, individual wires can be fed to a percutaneous connector or implantable wireless interface to allow either recording or electrical stimulation of the facial nerves. A summary of the features of these interfaces is shown in the accompanying TABLE.

FIGURE 2.

Demonstration of dynamic stimulation of paralyzed contralateral facial musculature. Implants with flexible muscle stimulation electrodes and EMG recording array are utilized to capture and stimulate symmetrical facial movement with an implantable pulse generator, reproduced with permission from McDonnall D and Ward PD [26].

FIGURE 3.

Electrodes used to interface peripheral nerves classified according to their invasiveness and selectivity. Images show examples of (A) cuff electrode, (B) flat interface nerve electrode (FINE), (C) longitudinal intrafascicular electrode (LIFE), (D) transverse intrafascicular multichannel electrode (TIME), (E) multielectrode array (USEA), (F) sieve electrode, and (G) microchannel electrode. Reproduced with permission from del Valle et al [27].

Table.

Comparison of Emerging Peripheral Nerve Interface Devices technologies

| Direct Functional Connections to Nerves | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cuff Electrodes | Flat interface nerve electrodes- (FINE) | Penetrating Nerve Arrays of Electrodes | Regenerative Electrodes | Regenerative Peripheral Nerve Interface (RPNI) | |

| Electrode Structure |

|

|

|

|

|

| Interface |

|

|

|

|

|

| Advantages |

|

|

|

|

|

| Limitations |

|

|

|

|

|

Cuff Electrodes

The simplest form of direct nerve interface would be to place an electrode on the surface of the nerve. This interface typically includes 1-3 exposed-tip metal wires incorporated into a tube made of a flexible silicone polymer [28]. The electrodes are used in a monopolar, bipolar, or tripolar configuration to record activity from or induce activity in the nerve [28]. Typically only 1 channel of information can be recorded from the electrodes to monitor activity. This signal is a sum of activity in the nerve, and it fails to capture the intricacies of the separate nerve fascicles activating distinct muscles groups.

FINE Electrodes

Flat Interface Nerve Electrodes (FINE) are a redesigned version of the standard cuff electrode. Whereas standard cuff electrodes stimulate or record from only the surface of the nerve, FINE devices reshape the nerve into a flatter footprint [29]. These devices reshape the nerve such that the individual nerve fascicles are positioned near the surface of the epineurium. These interfaces may include up to 14 individual electrodes to either record or stimulate the nerve. With this reshaping, it becomes feasible to activate individual nerve fascicles with far greater selectivity that can be achieved with standard surface cuff electrodes[30]. With multiple electrodes, it may also be possible to isolate activity generated from individual fascicles using source localization techniques [31]. More recently, these devices have been implanted on residual nerves in amputees to electrically stimulate individual sensations as well as activation of the hypoglossal nerve for laryngeal elevation as a protective mechanism of deglutition or swallowing[32, 33].

Penetrating Nerve Arrays of Electrodes

Two major technologies utilize penetrating arrays of electrodes implanted intrafascicularly into nerve. The first technology utilizes multiple small, stiff wires, typically constructed from tungsten or platinum-iridium alloys. Wire diameters for these devices are25-75 micrometers [34]. A microfabricated silicon-based electrode array developed at University of Utah exploits this technology to create up to 100contact points per nerve [35]. Individual tines are constructed of various lengths to allow interfacing to multiple fascicles within the nerve [36]. Performance degrades over approximately 6 months, likely caused by the mechanical mismatch between the hard electronic interface and the soft neural tissue [37]. Recently, these devices were used to electrically stimulate peripheral sensory nerves in amputated limbs and restore sensation. Given the size and density of these electrode arrays, pneumatic insertion tools must be used to penetrate the nerve [38]. Bleeding and trauma have been reported when using this device for brain implantation [39].

Regenerative Electrodes

In situations where the innervating nerve has been divided, or it is acceptable to surgically divide it, a regenerative electrode interface can be used. The largest advantage of regenerative electrodes is increased selectivity compared to surface or penetrating arrays. A sieve regenerative electrode consists of a porous sheet of material that is affixed to the end of the divided nerve (or between cut nerve ends) to allow the axons or fascicles to regrow through the channels [40]. Electrodes are incorporated within the holes or at the sieve entrance. Devices may utilize a flat inline structure [41] or channels of mixed sizes to allow regeneration of distinct fascicles [42, 43]. Electrodes may be placed on the surface of the channels and may allow unidirectional or bidirectional interfacing[44]. Penetrating electrodes can be affixed inside the channel such that as the nerve regrows through the channel, it interfaces with the electrodes that are already in place [45]. While regenerative interfaces afford high selectivity, they are limited by mechanical mismatch between hard electrode materials and fragile neural tissue.

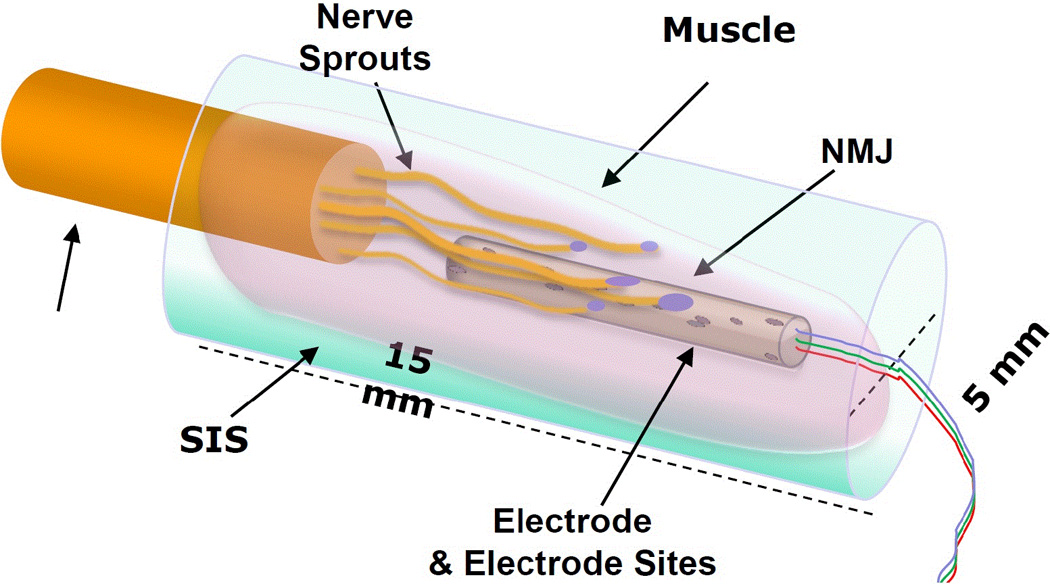

Muscle Interface Electrodes

Our team has begun developing a regenerative peripheral nerve interface (RPNI) that addresses this mechanical mismatch [46–48]. Rather than directly interfacing to the nerve, muscle tissue is used as a mechanical intermediary between the electrode and the nerve. As the nerve regenerates into the muscle tissue, the neural signals are amplified 10-100X by the muscle [49]. This interface strategy was developed for the primary purpose of interfacing with residual nerves in an amputated limb. However, pilot studies are underway to explore utilizing this technique for interfacing in other applications [50]. A schematic of the RPNI is shown in FIGURE 4 [51]. While these technologies are currently in various stages of research and development to interface directly with the facial nerves, it may be possible to interface with the muscle instead, with improve signal clarity and biocompatibility.

FIGURE 4.

Schematic of Regenerative Peripheral Nerve Interface (RPNI). SIS is small intestine submucosal tissue. NMJ is neuromuscular junction. Unlabeled arrow denotes neural input.

EMERGING TECHNOLOGIES

A variety of emerging technologies are in preclinical trials and on the horizon for treatment of facial paralysis. A team based at Ripple, llc (Salt Lake City, UT) is developing a fully implantable system for restoration of eye-blink in hemiparalysis patients [52]. The overall concept of the device is to record electromyographic (EMG) signals from a small electrode implanted in the orbicularis oculi muscle on the healthy side of the face [53]. When activity is detected on this EMG electrode, electrical stimulation pulses are delivered to either surface or percutaneous electrodes inserted into / on the paretic muscle. While providing some degree of blink restoration, restored blinks may appear as spasms. Despite this limitation, the device does maintain lubrication and protection of the eye. While prior studies have demonstrated this system in an intra-operative environment, development is underway to make this system fully implantable to deploy for long-term restoration in these patients [54, 55].

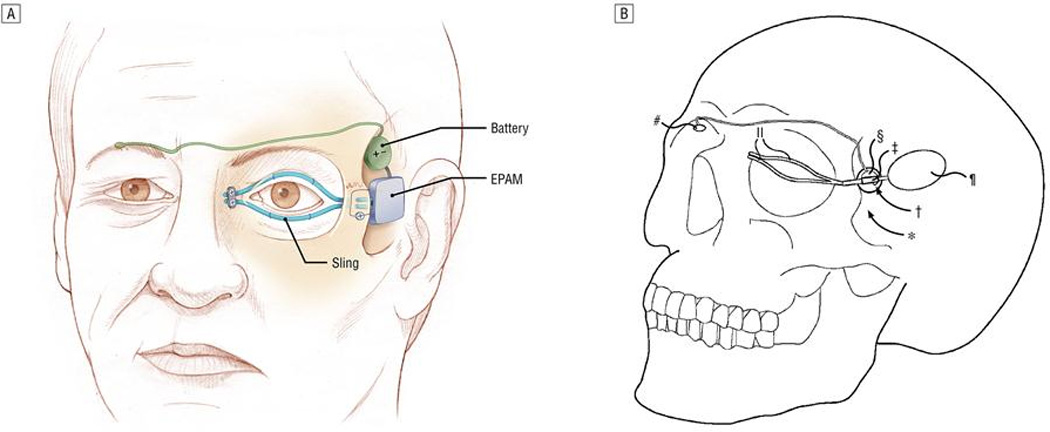

The majority of bioengineered interface strategies rely on reconnecting or reanimating intact neuromuscular systems. In some patients, the muscle or nerve tissue is no longer viable for recording or stimulation. In the eyelid, the muscle grafts are difficult to transfer and unlikely to provide the force generating capacity necessary to restore lost function. Although slings and weights afford some eye protection [56], new alternatives are emerging. Ledgerwood et al has developed an electroactive polymer artificial muscle device that could potentially restore lost muscular contraction for use as an eye blink prosthesis[57] (FIGURE 5). In preliminary studies, these devices induced minimal fibrous capsule response and no evidence of extensive inflammation up to one year[51]. During accelerated in vivo activation of the implants, the device did not exert visible movements or forces on the tissue, despite requiring high voltages that may not be achievable in a fully implantable system [51]. Future studies are needed to determine the clinical potential of these devices. Modifications of the strategy may be possible using other movable conductive polymers, including PEDOT[58] and polypyrrole [59, 60].

FIGURE 5.

Use of electroactive polymer artificial muscle (EPAM) to induce orbicularis oculi stimulation and symmetric closure with contralateral eye, reproduced with permission from Ledgerwood LG et al [51].

While development for wireless interfaces for facial paralysis is still limited, extensive efforts are underway for interfacing with other neural and muscular tissues. Much of this research may eventually have applicability to facial reanimation. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) is developing reliable nerve interfaces as part of their revolutionizing prosthetics program, a program focused on finding approaches that will allow amputees to control prosthetic limbs. Advances in this program could be applied to facial nerve prostheses as well. Most patients requiring these interfaces need solutions that will last a lifetime, and the discipline of neural engineering is improving long-term interface strategies. Commercial entities are also branching into new frontiers, utilizing neuroprosthetic interfaces for hypoglossal stimulation for obstructive sleep apnea, long-term spinal stimulation for pain, peripheral nerve stimulation for bladder control, and countless other examples. Given the range of new technologies on the horizon, there is ample reason for optimism regarding future treatment.

CONCLUSION

The treatment of facial paralysis has advanced dramatically in recent years. Approaches for restoring function include a spectrum of surgical approaches. Progress with tissue-engineered constructs and bioelectrical interfaces may eventually allow for a more natural and integrative endplate interface, improving cortical plasticity and ability to achieve a spontaneous smile. The evolution of surgical technique and new technology both hold promise for improving treatment of these patients.

KEY POINTS.

Advances in tissue engineering and nerve regeneration include novel regenerative scaffolds, neuromuscular interfaces, and replacement tissues that hold promise in facial reanimation.

Refinements in surgical technique, including nerve substitution targeted reinnervation, and control of tone and excursion may decrease donor site morbidity while improving smile outcomes.

Combining regenerative technologies with surgical innovation may optimize fine motor control and functional outcomes.

Acknowledgements

The authors with to acknowledge Jennifer Kim, M.D. for sharing her perspective on clinical approaches to facial reanimation and potential of bioelectrical prosthesis for facial reanimation.

Funding: This work was sponsored by the Defense Advanced Research Agency (DARPA) MTO under the auspices of Dr. Jack Judy / Doug Weber through the Space and Naval Warfare Systems Center, Pacific Grant/Contract No. N66001-11-C-4190 and NIH grant 1K08DC012535

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None.

Disclosures:

None.

REFERENCES AND RECOMMENDED READING

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

■ of special interest

■■ of outstanding interest

- 1. Faris C, Lindsay R. Current thoughts and developments in facial nerve reanimation. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;21:346–352. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e328362a56e. This work focuses on smile reanimation in acute and chronic facial paralysis.

- 2. Alam DS, Haffey T, Vakharia K, et al. Sternohyoid flap for facial reanimation: a comprehensive preclinical evaluation of a novel technique. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2013;15:305–313. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2013.287. This is the first article to propose the sternohyoid as a suitable alternative for free flap transfers, and outlines several potential advantages over the gracilis free flap for facial reanimation

- 3.Sameem M, Wood TJ, Bain JR. A systematic review on the use of fibrin glue for peripheral nerve repair. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127:2381–2390. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182131cf5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sachanandani NFMD, Pothula AMD, Tung THMD. Nerve Gaps. Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery. 2014;133:313–319. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000436856.55398.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weber RA, Breidenbach WC, Brown RE, et al. A randomized prospective study of polyglycolic acid conduits for digital nerve reconstruction in humans. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;106:1036–1045. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200010000-00013. discussion 1046-1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu H, Holzwarth JM, Yan Y, et al. Conductive PPY/PDLLA conduit for peripheral nerve regeneration. Biomaterials. 2014;35:225–235. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siriwardane ML, Derosa K, Collins G, Pfister BJ. Controlled formation of cross-linked collagen fibers for neural tissue engineering applications. Biofabrication. 2014;6:015012. doi: 10.1088/1758-5082/6/1/015012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wrobel S, Serra S, Ribeiro-Samy S, et al. In Vitro Cell-seeded chitosan films for peripheral nerve tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part A. 2014 doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2013.0621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stoyanova II, van Wezel RJ, Rutten WL. In vivo testing of a 3D bifurcating microchannel scaffold inducing separation of regenerating axon bundles in peripheral nerves. J Neural Eng. 2013;10:066018. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/10/6/066018. This study showed ability to separate nerve fascicles based on size using a specialized microchannel scaffold, which may be of help with optimizing axonal guidance.

- 10.Chen Z, Pradhan S, Liu C, Le LQ. Skin-derived precursors as a source of progenitors for cutaneous nerve regeneration. Stem Cells. 2012;30:2261–2270. doi: 10.1002/stem.1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spector JG. Neural repair in facial paralysis: clinical and experimental studies. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1997;254(Suppl 1):S68–S75. doi: 10.1007/BF02439728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Armati PJ, Mathey EK. Clinical implications of Schwann cell biology. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2014;19:14–23. doi: 10.1111/jns5.12057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jesuraj NJ, Santosa KB, Macewan MR, et al. Schwann cells seeded in acellular nerve grafts improve functional recovery. Muscle Nerve. 2014;49:267–276. doi: 10.1002/mus.23885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jesuraj NJ, Nguyen PK, Wood MD, et al. Differential gene expression in motor and sensory Schwann cells in the rat femoral nerve. J Neurosci Res. 2012;90:96–104. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brenner MJ, Hess JR, Myckatyn TM, et al. Repair of motor nerve gaps with sensory nerve inhibits regeneration in rats. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:1685–1692. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000229469.31749.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hontanilla B, Qiu SS, Marre D. Effect of postoperative brachytherapy and external beam radiotherapy on functional outcomes of immediate facial nerve repair after radical parotidectomy. Head Neck. 2014;36:113–119. doi: 10.1002/hed.23276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Morales-Chavez M, Ortiz-Rincones MA, Suarez-Gorrin F. Surgical techniques for smile restoration in patients with Mobius syndrome. J Clin Exp Dent. 2013;5:e203–e207. doi: 10.4317/jced.51116. This study reported on patients with Mobius syndrome, with the authors favoring cross-facial grafting for unilateral paralysis and nerve transposition for bilateral paralysis.

- 18.Magill CK, Tong A, Kawamura D, et al. Reinnervation of the tibialis anterior following sciatic nerve crush injury: a confocal microscopic study in transgenic mice. Exp Neurol. 2007;207:64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanbouzi Husseini S, Kumar DV, De Donato G, et al. Facial reanimation after facial nerve injury using hypoglossal to facial nerve anastomosis: the gruppo otologico experience. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;65:305–308. doi: 10.1007/s12070-011-0468-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bianchi B, Ferri A, Ferrari S, et al. The masseteric nerve: a versatile power source in facial animation techniques. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;52:264–269. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2013.12.013. This article explores the benefits of the masseteric nerve for ipsilateral nerve transposition emphasizing consideratons of structure, function, and surgical outcomes.

- 21. Hontanilla B, Marre D, Cabello A. Masseteric nerve for reanimation of the smile in short-term facial paralysis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;52:118–123. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2013.09.017. This study reports on effectiveness of use of masseteric nerve to power smile in short term facial paralysis with favorable symmetry and function.

- 22. Chuang DC, Lu JC, Anesti K. One-stage procedure using spinal accessory nerve (XI)-innervated free muscle for facial paralysis reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132:117e–129e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318290f8cd. This article explains the effectiveness of one-stage procedure of XI-innervated free muscle for facial reanimation.

- 23.Bhama PK, Weinberg JS, Lindsay RW, et al. Objective Outcomes Analysis Following Microvascular Gracilis Transfer for Facial Reanimation: A Review of 10 Years' Experience. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2014 doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2013.2463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manktelow RT, Tomat LR, Zuker RM, Chang M. Smile reconstruction in adults with free muscle transfer innervated by the masseter motor nerve: effectiveness and cerebral adaptation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118:885–899. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000232195.20293.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tzou CH, Chuang DC, Chen HY. Cortical Adaptation Staging System: A New and Simple Staging for Result Evaluation of Functioning Free-Muscle Transplantation for Facial Reanimation. Ann Plast Surg. 2013 doi: 10.1097/sap.0000000000000064. This article presents a new 5-stage evaluation process for FFMT and cortical adaption. It may provide a simple, accurate and reliable alternative to the popular House-Brackmann staging.

- 26.McDonnall DWPD. An Implantable Neuroprosthesis for Facial Reanimation. Boston: International Facial Nerve Symposium; [Google Scholar]

- 27.del Valle J, Navarro X. Interfaces with the peripheral nerve for the control of neuroprostheses. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2013;109:63–83. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-420045-6.00002-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khodaparast N, Hays SA, Sloan AM, et al. Vagus Nerve Stimulation Delivered During Motor Rehabilitation Improves Recovery in a Rat Model of Stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2014 doi: 10.1177/1545968314521006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leventhal DK, Cohen M, Durand DM. Chronic histological effects of the flat interface nerve electrode. J Neural Eng. 2006;3:102–113. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/3/2/004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kent AR, Grill WM. Model-based analysis and design of nerve cuff electrodes for restoring bladder function by selective stimulation of the pudendal nerve. J Neural Eng. 2013;10:036010. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/10/3/036010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wodlinger B, Durand DM. Selective recovery of fascicular activity in peripheral nerves. J Neural Eng. 2011;8:056005. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/8/5/056005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schiefer MA, Freeberg M, Pinault GJ, et al. Selective activation of the human tibial and common peroneal nerves with a flat interface nerve electrode. J Neural Eng. 2013;10:056006. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/10/5/056006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hadley AJ, Kolb I, Tyler DJ. Laryngeal elevation by selective stimulation of the hypoglossal nerve. J Neural Eng. 2013;10:046013. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/10/4/046013. These results support the hypothesis that an implanted, advanced, neural interface system can stimulate increased laryngeal elevation.

- 34.Musallam S, Bak MJ, Troyk PR, Andersen RA. A floating metal microelectrode array for chronic implantation. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2007;160:122–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Christopher RB, Ian OM, Richard AN, Gregory AC. Selective neural activation in a histologically derived model of peripheral nerve. Journal of Neural Engineering. 2011;8:036009. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/8/3/036009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wark HAC, Dowden BR, Cartwright PC, Normann RA. Selective Activation of the Muscles of Micturition Using Intrafascicular Stimulation of the Pudendal Nerve. Emerging and Selected Topics in Circuits and Systems, IEEE Journal on. 2011;1:631–636. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Branner A, Stein RB, Fernandez E, et al. Long-Term Stimulation and Recording with a Penetrating Microelectrode Array in Cat Sciatic Nerve. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 2004;51:146–157. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2003.820321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rousche PJ, Normann RA. A method for pneumatically inserting an array of penetrating electrodes into cortical tissue. Ann Biomed Eng. 1992;20:413–422. doi: 10.1007/BF02368133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.House PA, MacDonald JD, Tresco PA, Normann RA. Acute microelectrode array implantation into human neocortex: preliminary technique and histological considerations. Neurosurgical focus [electronic resource] 2006:20. doi: 10.3171/foc.2006.20.5.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Navarro X, Calvet S, Rodriguez FJ, et al. Stimulation and recording from regenerated peripheral nerves through polyimide sieve electrodes. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 1998;3:91–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Clements IP, Mukhatyar VJ, Srinivasan A, et al. Regenerative Scaffold Electrodes for Peripheral Nerve Interfacing. Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering, IEEE Transactions on. 2013;21:554–566. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2012.2217352. This article highlights a potential state of the art regenerative neural interface strategy.

- 42.Musick KM, Chew DJ, Fawcett JW, Lacour SP. PDMS microchannel regenerative peripheral nerve interface; Neural Engineering (NER), 2013 6th International IEEE/EMBS Conference on; 2013. pp. 649–652. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Irina IS, Richard JAvW, Wim LCR. In vivo testing of a 3D bifurcating microchannel scaffold inducing separation of regenerating axon bundles in peripheral nerves. Journal of Neural Engineering. 2013;10:066018. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/10/6/066018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lago N, Udina E, Ramachandran A, Navarro X. Neurobiological assessment of regenerative electrodes for bidirectional interfacing injured peripheral nerves. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2007;54:1129–1137. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2007.891168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seifert JL, Desai V, Watson RC, et al. Normal molecular repair mechanisms in regenerative peripheral nerve interfaces allow recording of early spike activity despite immature myelination. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2012;20:220–227. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2011.2179811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baldwin JF, Washabaugh EP, Moon JD, et al. Poly (3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) on decellular scaffolding interrupts grafted muscle revascularization; Neural Engineering (NER), 2013 6th International IEEE/EMBS Conference on; 2013. pp. 1461–1464. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kung TA, Bueno RA, Alkhalefah GK, et al. Innovations in prosthetic interfaces for the upper extremity. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132:1515–1523. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182a97e5f. This review highlights advanced technologies in the peripheral nervous system that could be applied for facial reanimation.

- 48.Urbanchek MG, Shim BS, Baghmanli Z, Wei B, Schroeder K, Langhals NB, et al. Conduction Properties Of Decellularized Nerve Biomaterials. IFMBE Proc. 2010;32:430–433. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-14998-6_109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Larson JV, Goretski SA, Cockrum JW, Urbanchek MG, Cederna PS, Langhals NB. Electrode characterization for use in a Regenerative Peripheral Nerve Interface; Neural Engineering (NER), 2013 6th International IEEE/EMBS Conference on; 2013. pp. 629–632. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Langhals NB, Cederna PS, Urbanchek MG. Peripheral nerve interface devices for treatment and prevention of neuromas. 13/944,167 US Patent App. 2013

- 51.Ledgerwood LG, Tinling S, Senders C, Wong-Foy A, Prahlad H, Tollefson TT. Artificial muscle for reanimation of the paralyzed face: durability and biocompatibility in a gerbil model. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2012;14:413–418. doi: 10.1001/archfacial.2012.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McDonnall D, Guillory KS, Gossman MD. Restoration of blink in facial paralysis patients using FES. Neural Engineering, 2009., NER '09. 4th International IEEE/EMBS Conference on. 2009:76–79. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yatsenko D, McDonnall D, Guillory KS. Simultaneous, proportional, multi-axis prosthesis control using multichannel surface EMG. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2007;2007:6134–6137. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2007.4353749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McDonnall D, Hiatt S, Smith C, Guillory KS. Implantable multichannel wireless electromyography for prosthesis control. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2012;2012:1350–1353. doi: 10.1109/EMBC.2012.6346188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. McDonnall D, Askin R, Smith C, Guillory KS. Verification and validation of an electrode array for a blink prosthesis for facial paralysis patients; Neural Engineering (NER), 2013 6th International IEEE/EMBS Conference on; 2013. pp. 1167–1170. This article highlights advanced electrode technology for facial reanimation.

- 56.Senders CW, Tollefson TT, Curtiss S, Wong-Foy A, Prahlad H. Force requirements for artificial muscle to create an eyelid blink with eyelid sling. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2010;12:30–36. doi: 10.1001/archfacial.2009.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tollefson TT, Senders CW. Restoration of Eyelid Closure in Facial Paralysis Using Artificial Muscle: Preliminary Cadaveric Analysis. The Laryngoscope. 2007;117:1907–1911. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31812e0190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Abidian MR, Kim DH, Martin DC. Conducting-Polymer Nanotubes for Controlled Drug Release. Advanced Materials. 2006;18:405–409. doi: 10.1002/adma.200501726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Smela E. Conjugated Polymer Actuators for Biomedical Applications. Advanced Materials. 2003;15:481–494. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Daneshvar ED, Smela E. Characterization of Conjugated Polymer Actuation under Cerebral Physiological Conditions. Advanced Healthcare Materials. n/a-n/a. 2014 doi: 10.1002/adhm.201300610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]