Abstract

Background and Aims

The burden of premature mortality due to opioid-related death has not been fully characterized. We calculated temporal trends in the proportion of deaths attributable to opioids and estimated years of potential life lost (YLL) due to opioid-related mortality in Ontario, Canada.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

Ontario, Canada.

Participants

Individuals who died of opioid-related causes between January 1991 and December 2010.

Measurements

We used the Registered Persons Database and data abstracted from the Office of the Chief Coroner to measure annual rates of opioid-related mortality. The proportion of all deaths related to opioids was determined by age group in each of 1992, 2001 and 2010. The YLL due to opioid-related mortality were estimated, applying the life expectancy estimates for the Ontario population.

Findings

We reviewed 5935 opioid-related deaths in Ontario between 1991 and 2010. The overall rate of opioid-related mortality increased by 242% between 1991 (12.2 per 1 000 000 Ontarians) and 2010 (41.6 per 1 000 000 Ontarians; P < 0.0001). Similarly, the annual YLL due to premature opioid-related death increased threefold, from 7006 years (1.3 years per 1000 population) in 1992 to 21 927 years (3.3 years per 1000 population) in 2010. The proportion of deaths attributable to opioids increased significantly over time within each age group (P < 0.05). By 2010, nearly one of every eight deaths (12.1%) among individuals aged 25–34 years was opioid-related.

Conclusions

Rates of opioid-related deaths are increasing rapidly in Ontario, Canada, and are concentrated among the young, leading to a substantial burden of disease.

Keywords: Burden of disease, drug toxicity, mortality, observational epidemiology, opioid analgesics, pharmacoepidemiology

Introduction

The use of opioids to treat chronic non-cancer pain is the subject of considerable debate due to a lack of evidence of efficacy when used over long durations, and increasing concerns regarding addiction and overdose with these commonly prescribed analgesics [1–3]. Several studies have demonstrated a marked increase in opioid dispensing, use of high-dose opioids and opioid-related deaths in North America [1–4]. These trends have led to significant concern among clinicians and policymakers, as well as the wider public regarding the safety of these medications [4–7].

Loss of life due to opioid overdose poses a considerable societal burden, especially in light of the number of such deaths among young and middle-aged adults. In North America, most opioid-related deaths occur in people younger than 55 years of age [8–10]. Moreover, recreational use of opioids among adolescents is increasing, with approximately one in seven high school seniors and university students reporting past non-medical use of these drugs [11,12]. The economic impact of this premature mortality is substantial, with estimates exceeding $18 billion from lost future earnings in the United States in 2009 [13].

While the rising prevalence of opioid use and opioid-related death has been reported in several jurisdictions [10,14,15], estimates of the burden of premature death involving opioids are scarce, and limited by the under-reporting of opioid-related deaths [16,17]. The 2010 Global Burden of Disease Study recently published burden of disease estimates for mental health and substance use disorders, reporting that illicit drug use accounted for a large proportion of the global burden of disease for these conditions [16]. They estimate that 3.6 million years of life were lost in 2010 world-wide due to drug use disorders, defined as harmful use of, and dependence on opioids and cocaine. While these findings highlight the importance of the issue, the validity of their reliance on International Classification of Diseases (ICD) categories of drug-related disorders using multiple data sources is debated in the literature [18,19]. As discussed by the authors of the study, the use of these codes probably led to considerabe underestimation of the prevalence of events, and thus the burden of disease [16]. Accordingly, we used data abstracted directly from coroner's records to estimate the burden of opioid-related mortality in Ontario and the proportion of all deaths involving opioids among various age groups at the population-level.

Methods

Study setting and population

We conducted a serial cross-sectional study of all opioid-related deaths in Ontario, Canada between 1 January 1991 and 31 December 2010. Ontario is Canada's largest province, with more than 13.2 million residents in 2010, all of whom have access to publicly funded health insurance for physician and hospital services. This study was approved by the research ethics board of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto, Ontario. The reporting of this study aligns with Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for observational studies [20].

Opioid-related deaths

Information regarding opioid-related deaths was abstracted from records of all deaths involving drugs or alcohol from the Office of the Chief Coroner (OCC) of Ontario. In Ontario, all deaths that are sudden and unexpected, or unnatural, are investigated by the OCC to ascertain cause and manner of death. Data were abstracted for all deaths between 2007 and 2010 by S.C. using methods consistent with data abstracted and published previously [10]. If the abstractor was uncertain of the cause of death, the file was reviewed by I.A.D., D.N.J., or both. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus. Opioid-related deaths were defined by the coroner as those deaths in which postmortem toxicological analyses revealed opioid concentrations sufficiently high to cause death, or if a combination of drugs (including at least one opioid at clinically significant levels) contributed to death. Deaths were not defined as opioid-related if another drug was present on the toxicological analysis at concentrations sufficient to cause death. All deaths involving heroin (identified on the police record or by the presence of 6-monoacetylmorphine on postmortem toxicological analysis) with no other opioid present at time of death were excluded. We calculated annual rates of opioid-related deaths over the study period and used the Ontario Registered Persons Database (RPDB) to determine the demographic characteristics of all patients who died between 1991 and 2010.

Measures of burden

Patients were stratified into seven age groups (0–14, 15–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64 and 65 years or older) and the burden of opioid-related death was quantified in two ways. First, we calculated the proportion of deaths in each age group that involved an opioid, using the RPDB to identify deaths from all causes in Ontario. This analysis was performed at three time-points over our study period: 1992, 2001 and 2010. Secondly, we calculated the years of potential life lost (YLL) due to premature mortality using methods adapted from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) and Ontario Burden of Disease studies [17,21,22]. Specifically, the total number of deaths were calculated by sex and 5-year age group, and the standard loss function was defined using the life expectancy for the Ontario population [23]. Years of life lost were calculated without discounting as the product between the age- and sex-specific number of deaths and life expectancy. Overall estimates of years of life lost were calculated as the sum of all sex- and age-group pairs. In two sensitivity analyses, we first applied a 3% discounting rate to our primary analysis, and then replicated all analyses using standard life expectancy tables developed for the World Health Organization (WHO) 2008 Global Burden of Disease study [22]. YLL were reported overall and stratified into the age groups defined above, and calculated for each of 1992, 2001 and 2010.

Statistical analyses

We conducted descriptive analyses of all individuals whose deaths were opioid-related during our study period. Rates of opioid-related deaths and YLL were standardized to the population size each year using data from Statistics Canada. We used χ2 tests to test for differences in the opioid-related death rate between 1991 and 2010 and the Cochran–Armitage test to assess for a significant trend in the proportion of deaths related to opioids between 1992, 2001 and 2010. Finally, we fitted a logistic regression model to test for an interaction between age group and year in the risk of opioid-related death. All tests were two-sided with a 5% probability of type I error as the threshold for statistical significance. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences.

Results

Opioid-related death

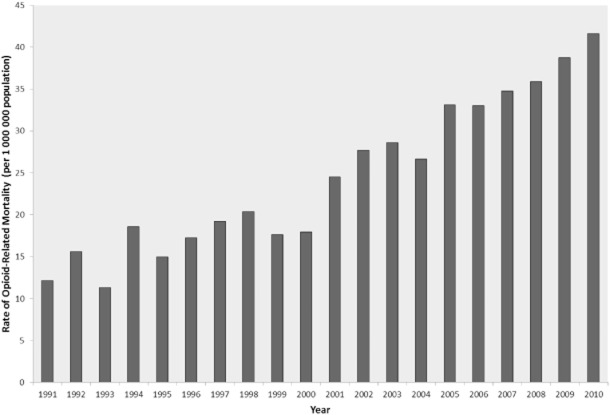

During the 20-year study period, we identified 5935 people whose deaths were opioid-related in Ontario. The median age at death was 42 years (interquartile range 34–50 years), 64.4% (n = 3822) of decedents were men and 90.0% (n = 5340) lived in an urban neighborhood. During the study period, rates of opioid-related death increased dramatically, rising 242% from 12.2 deaths per million in 1991 (127 deaths annually) to 41.6 deaths per million in 2010 (550 deaths annually; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Annual rate of opioid-related mortality (per 1 000 000 population) in Ontario, 1991–2010. Deaths abstracted from the Office of the Chief Coroner of Ontario were deemed opioid-related by the coroner if post-mortem toxicological analysis revealed opioid concentrations sufficiently high to cause death, or if a combination of drugs (including at least one opioid at clinically significant levels) contributed to death. Rates presented per 1 000 000 population

Burden of opioid-related mortality

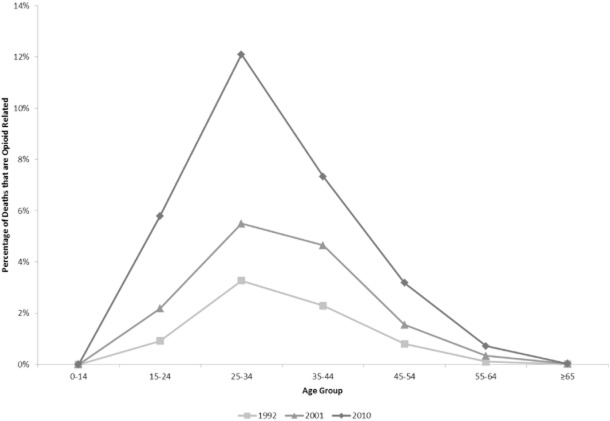

The proportion of all deaths related to opioids rose threefold between 1992 and 2010, from 0.2 to 0.6% (P < 0.0001; Table 1). This proportion increased significantly within each age group (P < 0.05), with the exception of the youngest age group, in which the small number of deaths precluded statistical analysis (Table 1; Fig. 2). Results of the logistic regression analysis incorporating an interaction between year and age group suggested that the increase in the proportion of deaths that were opioid-related differed significantly between groups (P = 0.007). The highest absolute increase occurred among individuals aged 25–34 years, in whom the proportion of deaths related to opioids increased from 3.3% in 1992 to 12.1% in 2010. The highest relative increases occurred among people aged 15–24 years (a 6.3-fold increase, from 0.9 to 5.8% of all deaths) and those aged 55–64 years (also a 6.3-fold increase, from 0.1 to 0.7% of all deaths).

Table 1.

Years of life lost due to premature deaths related to opioid overdose in Ontario, 1992, 2001 and 2010

| Age group (years) | 1992 | 2001 | 2010 | P-valueb | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total deaths | Opioid-related deaths | YLL | YLL per 1000 population | Total deaths | Opioid-related deaths | YLL | YLL per 1000 population | Total deaths | Opioid-related deaths | YLL | YLL per 1000 population | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||||||||||

| 0–14 | 1 784 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 277 | ≤5a | 145 | 0.13 | 1 287 | ≤5a | 82 | 0.08 | – |

| 15–24 | 984 | 9 (0.9%) | 556 | 0.74 | 687 | 15 (2.2%) | 910 | 1.13 | 674 | 39 (5.8%) | 2 371 | 2.59 | <0.0001 |

| 25–34 | 1 590 | 52 (3.3%) | 2693 | 2.81 | 964 | 53 (5.5%) | 2 769 | 3.25 | 926 | 112 (12.1%) | 5 845 | 6.56 | <0.0001 |

| 35–44 | 2 398 | 55 (2.3%) | 2353 | 2.84 | 2 301 | 107 (4.7%) | 4 598 | 4.48 | 1 868 | 137 (7.3%) | 5 817 | 6.19 | <0.0001 |

| 45–54 | 3 857 | 31 (0.8%) | 1030 | 1.74 | 4 703 | 73 (1.6%) | 2 444 | 2.94 | 5 271 | 168 (3.2%) | 5 733 | 5.46 | <0.0001 |

| 55–64 | 8721 | 10 (0.1%) | 254 | 0.55 | 7 748 | 26 (0.3%) | 684 | 1.25 | 9 696 | 70 (0.7%) | 1 794 | 2.26 | <0.0001 |

| ≥65 | 54 604 | 8 (0.0%) | 119 | 0.19 | 63 781 | 16 (0.0%) | 244 | 0.33 | 70 554 | 23 (0.0%) | 287 | 0.31 | 0.047 |

| Total | 73 938 | 165 (0.2%) | 7006 | 1.34 | 81 461 | 290a (0.4%) | 11 794 | 1.99 | 90 276 | 549a (0.6%) | 21 927 | 3.33 | <0.0001 |

YLL = years of life lost.

Cell sizes less than 6 are suppressed due to institutional privacy regulations. Column totals do not include suppressed cell sizes in age group 0–14.

P-value for Cochrane–Armitage test for trend in proportion of deaths that are opioid-related.

Figure 2.

Proportion of all deaths that are opioid-related, by age group, 1992, 2001 and 2010. The proportion of deaths in each age group that involved an opioid was calculated using opioid-related death data abstracted from the Office of the Chief Coroner of Ontario and deaths from all causes identified using the Ontario Registered Persons Database. This analysis was performed at three time-points over our study period: 1992, 2001 and 2010

The annual YLL due to premature death involving opioids increased threefold, from 7006 years (1.3 years per 1000 population) in 1992 to 21 927 years (3.3 years per 1000 population) in 2010 (Table 1). In 2010, deaths among individuals aged 25–54 accounted for 17 395 YLL, or 79.3% of all years lost due to premature opioid-related mortality. In a sensitivity analysis applying a 3% discounting rate to the Ontario estimates, the YLL increased from 3864 years in 1992 to 12 413 years in 2010 (Supporting information, Table S1). These findings were consistent when modeling life expectancy using the 2008 GBD life tables (Supporting information, Table S2).

Discussion

In this population-based analysis of opioid-related deaths, we found that the burden of premature mortality from opioids has increased dramatically during the past two decades. In 2010, approximately one of every 170 deaths (0.6%) was related to opioids, accounting for more than 20 000 YLL annually. Extrapolating these findings to the United States (where rates of opioid use, misuse and death are comparable to those in Canada), opioid-related deaths accounted for more than half a million YLL annually. Equally striking is that among adults aged 24–35 years, almost one in eight deaths involved an opioid.

The extraordinary number of YLL due to premature death related to opioids reflects in part the disproportionate number of these deaths among younger individuals, and highlights the public health and societal burden of opioid overdose. It is particularly concerning that the YLL almost doubled from 2001 to 2010, indicating a significant and dramatic rise in the impact of opioid overdose over the last decade. Indeed, by 2010 the YLL attributable to opioid-related deaths in our study (21 927 years) exceeded that attributable to alcohol use disorders (18 465 years) and pneumonia (18 987 years), and greatly exceeded that from HIV/AIDS (4929 years) and influenza (2548 years) in Ontario [17,21].

Our findings align with those of the 2010 GBD study, which demonstrated an increasing burden of drug dependence over the last two decades, and suggested that this burden is driven largely by YLL due to premature mortality [16]. The consistency between these two studies highlights the global relevance of drug-related disorders, and opioid-related death in particular.

A key strength of our study is the use of data abstracted directly from coronial records to determine the prevalence of opioid-related deaths. All unexpected and unnatural deaths in Ontario are investigated by a coroner, and their determination of opioid-related death is based typically on postmortem toxicological analyses. Therefore, our estimates are likely to provide a more accurate assessment of the burden of opioid-related death, with very little misclassification. In contrast, previous studies in this area have relied upon ICD codes and multiple data sources (e.g. vital registration, verbal autopsies, surveillance data) to diagnose drug dependence [16,24], a method which has questionable validity [18]. Indeed, the authors of the GBD study discuss this as a key limitation of their analysis, and suggest that their results probably underestimate the true burden of drug use disorders for this reason [16]. However, several limitations of our study also merit emphasis. First, we focused our analysis on years of potential life lost, and were unable to estimate the impacts of reduced functioning from living with opioid dependence or addiction. As a result, our findings underestimate the true burden of opioid use, abuse and overdose. Secondly, we were unable to account for potential quality of life improvements that may be associated with treatment of chronic pain, and so could not measure the downstream economic and societal implications of pain management. Thirdly, people prescribed opioids may have other comorbid conditions that could contribute to lower life expectancies than the general population, or may become addicted to other harmful substances in the absence of prescription opioids. As a result, we may have overestimated the YLL due to premature mortality in our analyses. However, given the young age at which most opioid-related deaths occur [8,10], widespread prescribing of opioids [14,25], as well as the high prevalence of non-medical use of these drugs [14], it is likely that this had minimal impact on our findings. Finally, although we excluded deaths related to heroin using toxicological analysis and police records, it is possible that a small number of heroin-related deaths were misclassified as morphine-related.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the high burden of opioid-related deaths that results from the concentration of these deaths in younger populations. The finding that one in eight deaths among young adults were attributable to opioids underlines the urgent need for a change in perception regarding the safety of these medications.

Declaration of interests

This study was supported by a grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC) Drug Innovation Fund and the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES), a non-profit research institute sponsored by the Ontario MOHLTC. The design and conduct of the study, collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data, and preparation and review of the manuscript were conducted by the authors independently from the funding sources. No endorsement by ICES or the Ontario MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred. M.M.M. has received honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Bayer. All other authors report no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mike Campitelli for comments and feedback on study design and the Office of the Chief Coroner for Ontario which, as part of their public safety mandate, made available the relevant data on opioid-related deaths in Ontario.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web-site:

Table S1 Years of life lost due to premature mortality, using Ontario life tables, applying 3% discounting rate.

Table S2 Years of life lost due to premature mortality, using standard life tables from the 2008 Global Burden of Disease Study.

References

- 1.Kissin I. Long-term opioid treatment of chronic nonmalignant pain: unproven efficacy and neglected safety? J Pain Res. 2013;6:513–529. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S47182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christo PJ, Grabow TS, Raja SN. Opioid effectiveness, addiction, and depression in chronic pain. Adv Psychosom Med. 2004;25:123–137. doi: 10.1159/000079062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sehgal N, Colson J, Smith HS. Chronic pain treatment with opioid analgesics: benefits versus harms of long-term therapy. Expert Rev Neurother. 2013;13:1201–1220. doi: 10.1586/14737175.2013.846517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gomes T, Mamdani MM, Dhalla IA, Paterson JM, Juurlink DN. Opioid dose and drug-related mortality in patients with nonmalignant pain. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:686–691. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunn KM, Saunders KW, Rutter CM, Banta-Green CJ, Merrill JO, Sullivan MD, et al. Opioid prescriptions for chronic pain and overdose: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:85–92. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-152-2-201001190-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gomes T, Redelmeier DA, Juurlink DN, Dhalla IA, Camacho X, Mamdani MM. Opioid dose and risk of road trauma in Canada: a population-based study. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:196–201. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Medical Association Council on Science and Public Health. D-95.981. Improving medical practice and patient/family education to reverse the epidemic of nonmedical prescription drug use and addiction. 2008. American Medical Association. Available at: http://www.ama-assn.org//ama/pub/about-ama/our-people/ama-councils/council-science-public-health/reports/reports-topic.page (accessed 14 May 2014) (Archived at http://www.webcitation.org/6PZWdbC4p)

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers and other drugs among women—United States, 1999–2010. MMWR. 2013;62:537–542. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Warner M, Chen LH, Makuc DM, Anderson RN, Minino AM. Drug poisoning deaths in the United States, 1980–2008. NCHS Data Brief. 2011;(81):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dhalla IA, Mamdani MM, Sivilotti ML, Kopp A, Qureshi O, Juurlink DN. Prescribing of opioid analgesics and related mortality before and after the introduction of long-acting oxycodone. Can Med Assoc J. 2009;181:891–896. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCabe SE, West BT, Teter CJ, Boyd CJ. Medical and nonmedical use of prescription opioids among high school seniors in the United States. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166:797–802. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCabe SE, Cranford JA, Boyd CJ, Teter CJ. Motives, diversion and routes of administration associated with nonmedical use of prescription opioids. Addict Behav. 2007;32:562–575. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inocencio TJ, Carroll NV, Read EJ, Holdford DA. The economic burden of opioid-related poisoning in the United States. Pain Med. 2013;14:1534–1547. doi: 10.1111/pme.12183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Policy Impact: Prescription Painkiller Overdoses. 2011. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/rxbrief/%20(accessed 14 May 2014) (Archived at http://www.webcitation.org/6PZX251PF)

- 15.Hakkinen M, Launiainen T, Vuori E, Ojanpera I. Comparison of fatal poisonings by prescription opioids. Forensic Sci Int. 2012;222:327–331. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Degenhardt L, Whiteford HA, Ferrari AJ, Baxter AJ, Charlson FJ, Hall WD, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to illicit drug use and dependence: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013;382:1564–1574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61530-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ratnasingham S, Cairney J, Rehm J, Manson H, Kurdyak PA. Opening Eyes, Opening Minds: The Ontario Burden of Mental Illness and Addictions Report An ICES/PHO Report. 2012. Toronto: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences and Public Health Ontario.

- 18.Quan H, Li B, Saunders LD, Parsons GA, Nilsson CI, Alibhai A, et al. Assessing validity of ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data in recording clinical conditions in a unique dually coded database. Health Serv Res. 2008;43:1424–1441. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00822.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saunders JB, Schukit MA, Sirovatka P, Regier DA. Diagnostic Issues in Substance Abuse Disorders. Refining the Research Agenda for DSM-V. 1st edn. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 20.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1453–1457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kwong JC, Crowcroft NS, Campitelli MA, Ratnasingham S, Daneman N, Deeks SL, et al. Ontario Burden of Infectious Disease Study (ONBOIDS): An OA HPP/ICES Report. 2010. Toronto: Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion, Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences.

- 22.Mathers CD, Vos T, Lopez AD, Salomon J, Ezzati M. National Burden of Disease Studies: A Practical Guide, edition 2.0. 2001. Geneva: World Health Organization, Global Program on Evidence for Health Policy.

- 23.Statistics Canada. Life Tables, Canada, Provinces and Territories [84-537-XIE]. 2006. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

- 24.Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, Baxter AJ, Ferrari AJ, Erskine HE, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013;382:1575–1586. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61611-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gomes T, Juurlink DN, Dhalla IA, Mailis-Gagnon A, Paterson JM, Mamdani MM. Trends in opioid use and dosing among socio-economically disadvantaged patients. Open Med. 2011;5:e13–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Years of life lost due to premature mortality, using Ontario life tables, applying 3% discounting rate.

Table S2 Years of life lost due to premature mortality, using standard life tables from the 2008 Global Burden of Disease Study.