Abstract

Tumor hypoxia is associated with increased therapeutic resistance leading to poor treatment outcome. Therefore the ability to detect and quantify intratumoral oxygenation could play an important role in future individual personalized treatment strategies. Positron Emission Tomography (PET) can be used for non-invasive mapping of tissue oxygenation in vivo and several hypoxia specific PET tracers have been developed. Evaluation of PET data in the clinic is commonly based on visual assessment together with semiquantitative measurements e.g. standard uptake value (SUV). However, dynamic PET contains additional valuable information on the temporal changes in tracer distribution. Kinetic modeling can be used to extract relevant pharmacokinetic parameters of tracer behavior in vivo that reflects relevant physiological processes. In this paper, we review the potential contribution of kinetic analysis for PET imaging of hypoxia.

Keywords: Cu-ATSM, 18F-FMISO, 18F-FETNIM, 18F-FAZA, oxygenation

Introduction

The majority of locally advanced solid tumors exhibit hypoxic and even anoxic regions that are heterogeneously distributed within the tumor mass [1]. These regions are a result of an imbalance between oxygen supply and consumption and can generally be divided into perfusion limited (acute) hypoxia, which is generated by the diffuse nature of tumor vasculature, and diffusion limited (chronic) hypoxia, which develops as the distance between tumor vasculature, and the expanding tumor cells increases. Additionally, cancer associated anemia may contribute to the formation of tumor hypoxia following a decrease in the bloods ability to carry the oxygen [2].

The intricate link between tumor hypoxia and increased malignancy is well established [3-5]. In addition, hypoxic tumor cells represent an important therapeutic problem because of increased resistance towards ionizing radiation and chemotherapy [6-9]. The therapeutic targeting of tumor hypoxia represents an attractive strategy for individualized therapy of cancer patients. In radiation oncology different approaches such as the use of adjuvant hypoxia sensitizers (e.g. nimorazole) during radiation therapy [10,11]; therapeutic combinations aiming to increase tumor oxygenation [12-14]; and modern high linear energy transfer radiation strategies (e.g. heavy ion therapy) [15] has been applied with varying results. Additionally, heterogeneous delivery of radiation, also termed dose painting, holds the potential to selectively increase radiation dose to areas with known therapeutic resistance, such as hypoxic tumor regions. This approach is extremely challenging, as it requires the ability to continuously identify regional changes in intratumoral oxygenation levels, and currently knowledge is very limited with regard to how regional oxygenation fluctuates during therapy [16,17]. Therefore methods that allow for identification of patients with hypoxic tumors that would benefit from hypoxia-modified treatment could improve treatment efficacy. However, presently no method has reached a position as a clinically accepted routine approach for identification of tumor hypoxia, even though a number of techniques have been evaluated to determine oxygenation in tissue. The polarographic electrode is currently the only method that can provide a direct measure of oxygen tension, and it has been considered as the gold standard for measurement of tumor pO2 over the last two decades [4,18-20]. In addition, a different type of electrode based on the principle of oxygen-induced quenching of light emitted by fluorescent dye, has also been used for this purpose [21-23]. Immunohistochemical staining of exogenous or endogenous surrogate markers of hypoxia in tumor biopsies is another approach often used to assess tumor oxygenation [24-26]. However, these needle-based methods have some limitations as they are invasive procedures and only applicable for tumors that are accessible with a needle. Moreover, these techniques only allows for the assessment of oxygenation in a limited volume of the tumor microenvironment. The heterogeneous distribution of hypoxic areas makes a non-invasive imaging approach attractive, and different techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) with oxygen sensitive probes have been applied for assessment of tumor oxygenation [27-30]. Additionally, positron emission tomography (PET) offers in vivo measurement and quantification of physiological processes with high temporal and adequate spatial resolution.

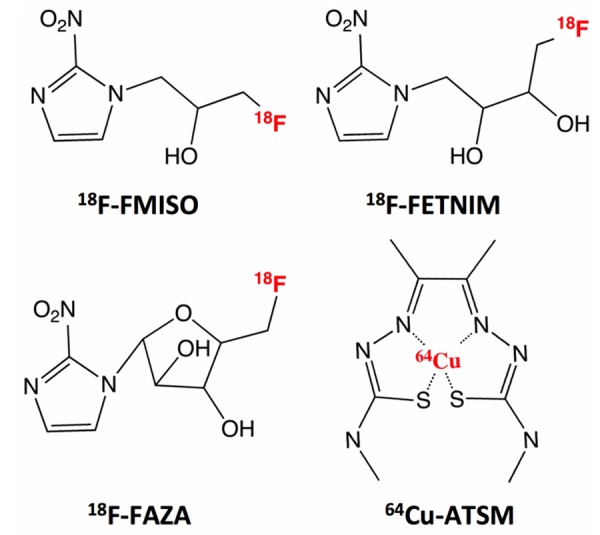

At present the radiolabelled glucose analog, 2-deoxy-2-(18F)fluoro-D-glucose (18F-FDG) is the most used PET tracer in clinical oncology. It utilizes that cancer cells take up greatly elevated levels of glucose, known as the Warburg effect [31,32]. Additionally, 18F-FDG has also been proposed as a surrogate marker of tumor hypoxia following the potential increased cell metabolism from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis when oxygen level drops [33]. This induce an increase in the uptake of glucose but despite this well-characterized connection, preclinical and clinical studies have reported conflicting results; but in general 18F-FDG cannot be considered as a consistent surrogate marker of hypoxia in tumors [34-39]. Accordingly, several radiotracers for specific PET imaging of hypoxia including 18F-Fluoromisonidazole 18F-FMISO, fluoroazomycin (18F-FAZA), fluoroerythronitroimidazole (18F-FETNIM) and copper(II)diacethyl-bis(N4-methylthiosemicarbazone) (Cu-ATSM) have been developed (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of hypoxia specific PET tracers. 18F-FMISO: 18F-fluoromisonidazole; 18F-FETNIM: 18F-fluoroerythronitroimidazole; 18F-FAZA: 18F-fluoroazomycin; 64Cu-ATSM: 64Cu(II)diacethyl-bis(N4-methylthiosemicarbazone). Besides 64Cu, Cu-ATSM can also be labeled with other radioactive copper isotopes such as 60Cu, 61Cu and 62Cu.

One of the advantages of PET is the ability to measure radiotracer concentration in tissue or organs. Semiquantitative approaches are often used for analysis of PET images but the main drawback is that it does not take into account variations caused by underlying processes such as tracer delivery, trapping, competition with other molecules, and physical clearance [40]. Dynamic PET can be used to study tracer pharmacokinetics and temporal changes in uptake, and clinical studies have indicated that valuable additional information can be obtained from the profile of time activity curves (TACs) [32,41,42]. Furthermore, mathematical modeling based on non-invasive imaging data can possibly be used to extract meaningful parameters of tracer accumulation and distribution kinetics [40,43-46].

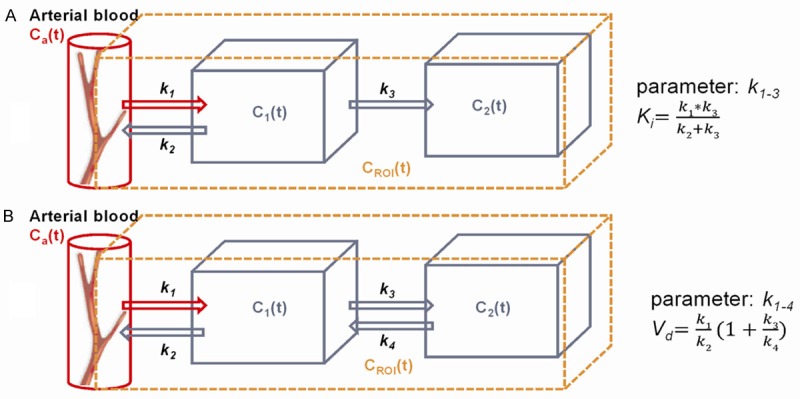

Basically, tracer kinetic modeling is based on a compartmental model that is comprised of a number of functional, homogenous units termed compartments. These are interpreted as separate, structureless pools of tracer in distinct state. The tracer transport between compartments can be described by rate parameters, and usually the models are described mathematically by first order differential equations. Figure 2 demonstrates the two most widely used model structures within tracer kinetic studies. While a 2-tissue reversible model is often applied in studies of neuroreceptor-ligands, a 2-tissue irreversible model has been implemented in most studies of hypoxia tracer kinetics [47,48]. In principle, additional compartments can be added to a model in order to obtain a more realistic interpretation of tracer kinetic behavior in vivo, including an increasing number of parameters. However, increased complexity affects the accuracy and reliability of the model parameter estimation due to limitation of the nonlinear minimization problem [49]. Therefore model selection should be considered as a balance between statistical accuracy and model complexity. As an alternative, graphical analysis is a more computational efficient way to calculate combinatorial parameters by turning a nonlinear problem into linear plots [50]. Thus the slope of the linear part of Patlak and Logan plots can be used to determine netto influx rate, Ki and distribution volume, Vd for tracers with irreversible and reversible uptake, respectively.

Figure 2.

Graphical representation of common 2-tissue compartment models. Model (A) is consisting of three components and each is a function of time expressed as time activity curves. Input function, Ca(t) consists primarily of arterial blood and interstitial space close to vessels. The C1(t) compartment represents unbound tracer in tissue whereas C2(t) compartment represents bound tracer. This model contains three kinetic parameters, k1-3. Model (B) contains the same number of compartments but kinetic parameter also includes the transport rate constant k4. Moreover, the netto influx parameter, Ki can be calculated based on k1-3 in a irreversible model, and k1-4 can be used to calculate the distribution volume, Vd in a reversible model.

Overall compartmental analysis provides a possibility to understand the tracer behavior in a specific tissue and allows for the derivation of important kinetic parameters. This can provide additional information on a metabolic processes at the molecular level and thereby potentially improve the diagnostic and prognostic potential of a PET tracer. This review focuses on studies where compartment/kinetic modeling has been applied on PET data for quantification of hypoxia.

18F-FMISO

The majority of hypoxia PET tracers belongs to a group of compounds termed nitroimidazoles that have been used intensively as immunological markers for immunohistochemical procedures and flowcytometry [51-55]. Nitroimidazoles enter cells by diffusion and are reduced by nitroreductases inversely correlated with oxygen tension. In the presence of oxygen they are able to leave the cell again, but under hypoxic conditions the nitroimidazoles become reduced and will be irreversibly trapped within the cells [56,57].

18F-Fluoromisonidazole (18F-FMISO) was the first nitroimidazole-based radiotracers for hypoxia PET imaging to be developed, and it has been extensively used in both preclinical and clinical studies [58-63].

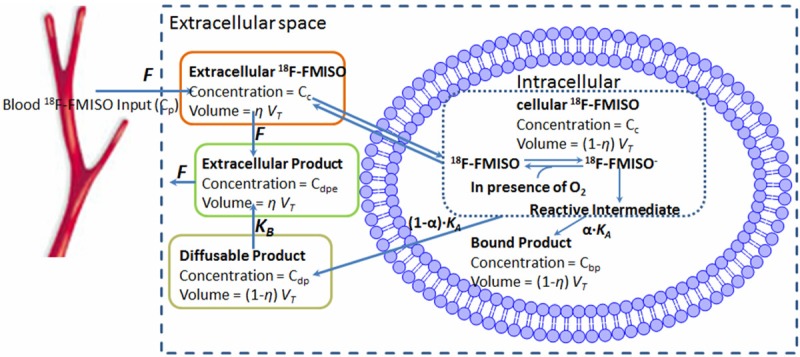

The kinetic profile and characteristics of 18F-FMISO has also been investigated in a number of studies applying various approaches. In 1995 Casciari et al. developed a mathematical model based on knowledge on the cellular metabolism and tracer transport in tissue. The main objective was to quantify 18F-FMISO reaction rate constant, KA, a parameter related to the level of cellular oxygen (see Figure 3). Models performance was tested using Monte Carlo simulation and fitted to 18F-FMISO time-activity PET data from human and rat tumors. This demonstrated the importance of including some transport limits such as parameter fixing of the compartments representing tracer in the tissue. In addition the effect of noise on accurately determination of KA was small when some parameters were fixed at physiological meaningful values; however, the accuracy of KA was sensitive to the accuracy of the fixed parameters [64].

Figure 3.

The model of 18F-FMISO transport and metabolism presented by Casciari et al. 18F-FMISO enters the target tissue by flood flow (F) and diffuse across the cell membrane, where it is reduced. KA is the rate constant describing the rate by which FMISO is reduced. Cellular accumulation of FMISO and washout of diffusible product is running side by side. Cc, Cp, Cbp, Cdp, Cdpe corresponds to 18F-FMISO concentration in tissue, in blood plasma, 18F-FMISO bound product and cellular diffusible product, respectively. VT, η are the tissue specific volume and dimensionless fractional variable. KA is related to the oxygen level and can be considered as a surrogate measure of hypoxia.

Kelly and Brady also did a simulation work on the spatiotemporal distribution of 18F-FMISO in tumor microenvironment by applying a modular approach to simulated data. They included parameters to model spatial diffusion of free 18F-FMISO and its reduced compounds and modified a conversional reversible 2-compartmental model, with a reaction-diffusion equation, in order to improve 18F-FMISO distribution dynamics [65]. The model was then used to generate simulated data based on patient plasma time activity curve as input. It was necessary to set transport parameter k4 = 0. Additionally, a number of technical limitations that influenced the model were identified. On the basis on this, the kinetic and spatial effects of diffusion could be disregarded in the data fitting process. The adaptive model illustrated that a reversible 2-compartment model with varying diffusion distances and diffusion coefficients was able to generate more realistic TACs. Moreover, it demonstrated that simulation models of tracer spatiotemporal distributions provides a options to investigate the effects of heterogeneity on TACs and the relationships between image data and molecular processes, prior to empirical studies.

Besides these simulation studies of 18F-FMISO, a limited number of preclinical studies in mice and rats have focused on kinetic modeling. Whisenant et al. did a study in nude mice bearing Trastuzumab-resistant breast tumors in order to test the reproducibility of kinetic parameters derived from dynamic PET scan protocols [66]. Mice received 60 min dynamic PET scan six hours apart with 18F-FLT and 18F-FMISO, respectively. They found that the distribution volume, Vd and the net influx constant, Ki were the most reproducible parameters for 18F-FMISO. In contrast transport constant k1 and trapping constant k3 were the most variable. For 18F-FLT Vd, k3, and Ki were shown to be the most reproducible parameters.

In another study Bejot et al. evaluated 18F-3-NTR, a 3-nitro-1,2,4-triazole analogue (N(1) substituted) (18F-3-NTR) against 18F-FMISO as hypoxia PET tracer in tumor bearing mice and concluded that 18F-3-NTR could not be considered a hypoxia imaging agent due to its poor binding capacity [67]. Furthermore, based on the Akaiki information criterion there was no benefit of applying a 3-compartment irreversible model to describe 18F-FMISO kinetics when compared to a 2-compartment irreversible model.

In a recent study, Bartlett et al. investigated a group of nude rats bearing prostate tumors in order to find a non-invasive approach based on dynamic PET for better identification of tumor hypoxia [23]. Voxelwise kinetic parameters calculated from 2-compartment model fitting to 18F-FMISO uptake data were compared to pO2 measurements. When k1 and k2 were constrained, 18F-FMISO trapping rate, k3 was shown to be a more robust discriminator for low pO2 within tumor tissue than a simple tissue-to-plasma ratio. This suggest that voxelwise based kinetic modeling could improve accuracy of tumor hypoxia estimation.

Finally, the use of kinetic modeling of 18F-FMISO has also been investigated in a few clinical studies. Bruehlmeier et al. used 15O-H2O to study the influence of perfusion on the pharmacokinetics of 18F-FMISO in eleven patients with brain cancer and observed an increased late uptake in glioblastomas [68]. Pixel-wise comparison showed a positive relationship between 15O-H2O and early uptake of 18F-FMISO, whereas no correlation was found for late 18F-FMISO distribution. Standard 2- and 3-compartment models and Logan graphical analysis were used to calculate distribution volumes and transport rate constants and found that a Vd above one was indicative of active 18F-FMISO uptake. Additionally, the 18F-FMISO uptake rate, k1 was increased in all tumor tissue, compared to values in white matter and in cortex. In meningioma they found the highest value for k1 of all brain tumors. This increase k1 permitted delineation of the meningioma in an early 18F-FMISO PET image, but the tumor did not exhibit subsequent 18F-FMISO accumulation and was not visualized in the late PET images. Accordingly, the 18F-FMISO distribution volume in the meningioma was not increased despite a high k1 value. However, despite Vd providing a good measure of 18F-FMISO accumulation, it was concluded that it does not offer additional information compared to tumor-to-background ratios of late PET images.

Using a similar experimental setup with 15O-H2O and 18F-FMISO, Bruehlmeier et al. applied graphical analysis on dynamic PET data from six dogs with spontaneous sarcomas [69]. They found that tumor tissue could be markedly delineated from surrounding tissue including muscles by positive influx rate Ki derived from a Patlak plot. The presence of tumor hypoxia was confirmed by eppendorf electrode measure- ment.

In a study of head and neck cancer patients, Thorwarth et al. performed quantitative image analysis based on irreversible compartmental modeling of dynamic 18F-FMISO PET data [70]. This model was different from previous approaches by including weighing factors for the respective model compartments. The input function was determined from the signal of a reference tissue and the irreversible model was applied to identify and quantify TACs using a voxel-to-voxel approach. Evaluation of model performance indicated that the parameters derived from the kinetic model were superior to SUV for quantification in extremely low oxygenated and necrotic tissue areas. In another study the same model was applied to a small group of head and neck cancer patients that were scanned dynamically for 60 min prior to radiotherapy [42]. Assessment parameters representing hypoxia and perfusion derived from the kinetic model were not able to predict treatment outcome. However, Thorwarth et al. introduced a novel parameter, termed the malignancy value, that was dependent on both hypoxia and perfusion characteristics of the tissue. This malignancy value could be used as a prognostic factor indicating that the parameters may provide additive information. Furthermore, in a preclinical study, Cho et al. adapted Thorwarth’s model for comparing perfusion and hypoxia parameters derived from MRI with 18F-FMISO PET in a rat prostate cancer model [71]. The tumor perfusion derived from DCE-MRI was found positively correlated with early 18F-FMISO PET but inversely correlated to late slope maps of the 18F-FMISO PET time-activity curve.

Wang et al. applied a generic irreversible 2-compartmental model to analyze dynamic 18F-FMISO PET dataset within three regions of an image phantom [72]. The purpose of the phantom study was to determine the statistical accuracy and precision of the kinetic analysis. The results from the phantom study was used for guidance in a clinical dynamic 18F-FMISO PET study of nine head and neck cancer patients with local squamous cell carcinoma [73]. Based on this they identified Ki as a potential hypoxia marker and found a significant correlation to 18F-FMISO tumor-to-blood ratio.

In addition to modeling of tumor hypoxia, 18F-FMISO has also been used in studies of ischemic stroke. Takasawa et al. performed a rat stoke study that included dynamic PET with 18F-FMISO. In order to obtain quantitative comparison between the tracer retention from affected and unaffected cerebral hemispheres, an irreversible compartmental model was used for calculation of k1 and Ki [74]. Immediately after the occlusion of the middle cerebral artery a remarkable increased Ki was observed in the affected site. This suggests that 18F-FMISO can potentially be used to visualize the occlusion at a very early stage. However, in spite of histological findings, no difference in either k1 and Ki was found between affected and unaffected cerebral hemispheres 48 hours after the occlusion. In another study Hong et al. used the dataset generated by Takasawa et al. to perform kinetic analysis [75]. Basis functions from plasma input compartment (BAFPIC) model is a modified version of the standard compartment model approach and can be applied to both reversible and irreversible models. In this study BAFPIC was compared to both conventional compartment modeling, as well as the most common analysis methods for generation of parametric maps. The BAFPIC method showed lower variability and bias than nonlinear least squares modeling in hypoxic tissue. In addition, voxel based parametric mapping of dynamic imaging was shown to be less affected by noise-induced variability compared to nonlinear least squares modeling and Patlak graphical analysis. BAFPIC could therefore potentially be applied to other tracers with irreversible characteristics, and although the focus of this study was on voxelwise modeling, other kinetic parameter estimations in regions with noise can be performed using the BAFPIC algorithm as well.

18F-FETNIM

Even though 18F-FMISO has been used extensively, a slow hypoxia specific retention and clearance from non-hypoxic tissue is a limitation and results in low tumor-to-background contrast [76]. To improve image quality 18F-labeled nitroimidazole analogs including 18F-FETNIM, 2-nitroimidazole nucleoside analog (18F-HX4) and 2-(2-Nitromidazole-1H-yl)-N-(2,2,3,3,3-pentafluoropropyl)acetamind (18F-EF5), that have structural modifications - with changed lipophilic properties, have been developed to overcome the basic pharmacokinetic limitations [44,77,78]. 18F-FETNIM was introduced as a novel hypoxia-specific PET tracer in 1995 and has shown promising results in clinical studies [77,79].

In studies in patients with head and neck cancer Lehtiö et al. performed compartmental analysis based on dynamic 18F-FETNIM PET scans [80,81]. They adapted the model previously introduced by Casciari et al. for 18F-FMISO metabolism and transport (Figure 3). Blood flow rate (F), tissue activity correction factors (β1, β2) and cellular 18F-FETNIM reaction rate (KA), considered the hypoxia specific binding rate, were estimated by fitting the model to dynamic PET data. They found that the level of tracer uptake (KA) was most sensitive to changes in oxygen in tissue with high blood flow. Furthermore, distribution volumes derived from Logan plots correlated positively with the tumor-to-plasma ratio but not with tumor-to-muscle ratio. This suggests that plasma should be preferred as reference tissue rather than muscle.

18F-FAZA

Like 18F-FETNIM, 18F-FAZA is a next generation nitroimidazole-based PET tracer. Several studies have compared the tracer kinetics of 18F-FAZA with 18F-FMISO and reported of improvements in washout from non-hypoxic tissue and faster renal clearance [82-84]. Moreover, a recent study of 50 patients confirmed the feasibility of using FAZA PET for detection of tumor hypoxia in clinic [85].

A few studies have focused on kinetic modeling of dynamic 18F-FAZA PET. Reischl et al. demonstrated an increased tumor to blood ratio due to faster vascular clearance of 18F-FAZA when compared to 18F-FMISO and that is one of most important criteria for hypoxia tracer development in relation to hypoxia imaging optimization [86].

Busk et al. reported a dynamic 18F-FAZA animal study in three tumor xenograft models of squamous cell carcinomas of the cervix. The dynamic data were analyzed by an irreversible 2-compartmental model. Overall variations in the pattern of TACs were tumor type dependent. The influx rate constant Ki was shown to have a strong correlation to late 18F-FAZA uptake in two of three tumors models. On the other hand, weak correlation between irreversible parameter k3 and late 18F-FAZA uptake was observed in two of three tumor models [87].

Two small clinical studies have used dynamic 18F-FAZA PET data to compare different kinetic models. While Shi et al. used a voxelvise approach to correlate model parameters of interest with perfusion measured by 15O-H2O PET in patients with head and neck cancer; Verwer et al. applied the Akaiki information criterion to evaluate model fitting to TACs obtained from nine non-small cell lung cancer patients [88,89]. Both studies concluded that a reversible 2-compartment model showed the best correlation and robustness with their expectations and assumptions.

Cu-ATSM

Beside the nitromidazole-based compounds, a copper labeled metallocomplex termed copper(II)diacethyl-bis(N4-methylthiosemicarbazone) (Cu-ATSM) has been applied as radiotracer for PET imaging of tumor hypoxia [90]. Image quality is generally superior to the nitroimidazoles, however, despite promising clinical performance [91-93], preclinical data from experimental hypoxia imaging is conflicting with regard to tracer selectivity [94-97]. The mechanism of tracer uptake and retention is still not fully understood but it is believed that Cu(II)-ATSM is reduced to the unstable [Cu(I)- ATSM]- complex in both hypoxic and normoxic cells. Under normoxic conditions [Cu(I)-ATSM]- is reoxidized and thereby able to of leave the cell. The reoxidation of [Cu(I)-ATSM]- is, however, not expected to occur under hypoxic conditions, and the electrochemically negative molecule becomes irreversibly trapped and dissociates [98,99].

As for the other hypoxia PET tracers there are only limited data concerning the pharmacokinetics of Cu-ATSM. A simulation work carried out by Holland et al. applied a model based on an in vitro study on cellular uptake and retention of 64Cu-ATSM in EMT6 murine carcinoma cells. The model demonstrated that a decrease in cellular pH may protonate the unstable Cu(I)-ATSM complex and increase the rate of dissociation [100]. The kinetic analysis was consistent with experimental cellular uptake.

Bowen et al. suggested an electrochemical models based on the retention mechanisms for 18F-FMISO and 61Cu-ATSM, respectively [101]. In this work the preclinical data were compared to transformation functions derived from tracer uptake and pO2 measurements. Comparisons between 61Cu-ATSM and 18F-FMISO uptake showed inconsistent results, but this could be due to the different retention mechanisms. However, the results suggested that 18F-FMISO uptake was superior for differentiation of a wide range of pO2 values, but 61Cu-ATSM uptake provided more reliable information on variations at low pO2 range.

In another study Dalah et al. performed a simulation work based on the model adapted from Kelly and Brady [102]. This refined model was used to simulate realistic TACs that were comparable to 64Cu-ATSM patient TACs and showed favorable tumor delineation in form of higher tumor to blood ratio compared to 18F-FMISO.

Kinetic modeling of Cu-ATSM PET has also been applied in a few animal studies. Lewis et al. evaluated Cu-ATSM retention in canine models of hypoxic myocardium [97]. Monoexponential analysis and 2-compartmental model fitting were applied to the TACs in order to determinate washout of Cu-ATSM from regions of the myocardium. Based on the assumption that the relationship between washout and retention is inverse proportional, they reported of an increase of Cu-ATSM retention in ischemic regions when compared to normal myocardium. Moreover, the data also indicated that Cu-ATSM retention in hypoxic regions of the myocardium was independent of increased perfusion and that there was no retention in necrotic tissue.

Recently, McCall et al. performed a preclinical study of 64Cu-ATSM uptake in rats bearing FaDu human head and neck cancer xenografts. Graphical analyses were used to derive the net influx parameter, Ki and distribution volume, Vd. In general, a stronger linear relationship was found for Logan plots but both parameters were significantly higher in tumor tissue when compared to muscle tissue. Additionally, a continuous increasing tumor-to-muscle ratio was observed [103].

Finally, Cu-ATSM has been used in multitracer PET studies where two or three tracers were administered with delayed injections. Following image separation, signal recovery was performed based on differences in tracer kinetics and physical decay. In a phantom study of 62Cu-ATSM and the perfusion PET tracer, 62Copper-pyruvaldehyde-bis[N4-methylthiosemicarbazone] (62Cu-PTSM), Rust et al. demonstrated a great similarity between perfusion and hypoxia parameters obtained by the dual tracer approach, and parameters estimated by single-tracer imaging [104]. The results were later confirmed by Black et al. that adapted the phantom study protocol and used it for 62Cu-ATSM and 62Cu-PTSM PET imaging in dogs with spontaneous tumors [105]. Rate constants obtained from irreversible 2-compartment modeling was used to evaluate the signal separation of the two PET tracers. However, while k1 and k2 could be recovered from the mixed PET signal the recovery of k3 was more problematic. The same group has also experimented with a triple-tracers setup including 18F-FDG [106]. Altogether, the multitracer approach can potential provide different functional information about physiological processes within a short period of time; thereby decreasing the possible effect of microenvironmental changes. However, there are some questions there needs to be address with regard to the long dynamic acquisition time, and the risk of losing information as a consequence of temporal overlap.

Table 1 summaries studies on kinetic modeling of hypoxia using PET tracers.

Table 1.

Overview of kinetic modeling work with regard to hypoxia using different hypoxia PET tracers

| Tracer | Image Targeting | Methods | Application | Species | Authors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18F-FMISO | Hypoxia | Voxelwise kinetic modeling | Oncology/Prostate tumor | Rat | Bartlett et al. [23] |

| Noninvasive pO2 measurement | |||||

| 18F-FMISO | - | Kinetic model | Oncology | Rat | Casciari et al. [64] |

| 3H-FMISO | Monte Carlo simulations | Patient | |||

| 18F-FMISO | Hypoxia, perfusion | Dynamic PET | Oncology/Brain tumor | Patient | Bruehlmeier et al. [68] |

| 15O-H2O | Kinetic models | ||||

| Logan graphical analysis | |||||

| 18F-FMISO | Hypoxia, perfusion | Patlak graphical analysis | Oncology/Spontaneous sarcomas | Dog | Bruehlmeier et al. [69] |

| 15O-H2O | |||||

| 18F-FMISO | Hypoxia | Modular simulation | Oncology/Model evaluation | Simulation work | Kelly and Brady et al. [65] |

| Probability density function | |||||

| 18F-FMISO | Hypoxia | Kinetic model | Oncology/Model evaluation | Phantom study | Wang et al. [72] |

| 18F-FMISO | Hypoxia | Pharmacokinetic analysis | Oncology/Head and neck cancer | Patient | Wang et al. [73] |

| Dynamic PET/CT | |||||

| 18F-FMISO | Hypoxia, perfusion | Dynamic PET | Oncology/Head and neck cancer | Patient | Thorwarth et al. [70] |

| Two compartment model | |||||

| 18F-FMISO | Hypoxia | Dynamic PET | Oncology/Radiotherapy | Patient | Thorwarth et al. [42] |

| Two compartment model | |||||

| 18F-FMISO | Hypoxia | DCE-MRI | Oncology/Prostate tumor | Rat | Cho et al. [71] |

| Dynamic PET | |||||

| Autoradiography | |||||

| 18F-FMISO | Hypoxia | Dynamic PET | Oncology/Non-immunogenic carcinoma | Mouse | Bejot et al. [67] |

| 18F-3-NTR | Compartment modeling | ||||

| 18F-FMISO | Hypoxia | Dynamic PET | Scan protocol validation | Mouse | Whisenant et al. [66] |

| 18F-FDG | Graphical analysis | ||||

| 18F-FDG | Graphical analysis | ||||

| 18F-FMISO | Stroke | Dynamic PET | Stroke | Rat | Takasawa et al. [74] |

| 18F-FMISO | Hypoxia | Dynamic PET | Stroke | Rat | Hong et al. [75] |

| Voxelwise Kinetic analysis based on basis function method | |||||

| 18F-FETMIN | Hypoxia | Dynamic PET | Oncology/Head and neck cancer | Patient | Lehtio et al. [80] |

| Tumor to plasma ratio | |||||

| Tumor to plasma ratio | |||||

| 18F-FETMIN | Hypoxia | Dynamic PET | Oncology/Head and neck cancer | Patient | Lehtio et al. [81] |

| Compartment analysis | |||||

| 18F-FAZA | Hypoxia | Dynamic PET | Oncology/Squamous cell carcinoma | Mouse | Busk et al. [87] |

| Immunohistochemical staining | |||||

| Immunohistochemical staining | |||||

| 18F-FAZA | Hypoxia, perfusion | Dynamic PET | Oncology/Head and neck cancer | Patient | Shi et al. [88] |

| 15O-H2O | Kinetic model | ||||

| 18F-FAZA | Hypoxia | Dynamic PET/CT | Oncology/No-small cell lung cancer | Patient | Verwer et al. [89] |

| 60Cu-ATSM | Hypoxia | Compartment analysis | Myocardial ischemia | Dog | Lewis et al. [97] |

| 64Cu-ATSM | |||||

| 64Cu-ATSM | |||||

| 64Cu-ATSM | Hypoxia | Non-steady-state kinetic simulations | Oncology/EMT6 murine carcinoma | Mouse | Holland et al. [100] |

| 61Cu-ATSM | Hypoxia | Electrochemical model | Oncology/Head and neck cancer | Patient | Bowen et al. [101] |

| 18F-FMISO | Transformation function | ||||

| pO2 microelectrode | |||||

| 64Cu-ATSM | Hypoxia | Kinetic modeling | Oncology/Radiotherapy | Simulation work | Dalah et al. [102] |

| 64Cu-ATSM | Hypoxia | Dynamic PET | Oncology/Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma | Rat | McCall et al. [103] |

| Autoradiography | |||||

| Immunohistochemical staining | |||||

| 62Cu-PTSM | Hypoxia, perfusion | Dynamic PET | Multiple tracer protocol | Simulation work | Rust et al. [104] |

| 62Cu-ATSM | 62Cu-ATSM | ||||

| 62Cu-PTSM | Hypoxia, perfusion | Dynamic PET | Multiple tracer protocol | Dog | Black et al. [105] |

| 62Cu-ATSM | Compartment analysis | Signal separation and recovery | |||

| 18F-FDG | Hypoxia, perfusion and glycolysis | Dynamic PET | Multiple tracer protocol | Dog | Black et al. [106] |

| 62Cu-PTSM | Compartment analysis | Signal separation and recovery | |||

| 62Cu-ATSM |

Challenges in kinetic modeling of hypoxia PET tracers

Studies on kinetic modeling of hypoxia PET tracer needs also deal with the issues, related to acquisition of dynamic PET data in general. The amplitude of noise can be influenced by several physical factors such as the radiopharmaceutical properties of the tracer, injected dose, frame duration, and the sensitivity of the PET camera. In addition, the size of the volumes of interest (VOI) or voxels will also have effect on the scale of noise. In quantitative analysis of dynamic PET data, the accuracy of kinetic parameter estimation is not only related to the signal to noise ratio, but also the number of model parameters and selection of estimation method [107].

Non-linear least square optimization is the most widely used technique to perform curve-fitting for parameter estimation in conventional compartment modeling [8,25,26]. The accuracy of both curve-fitting and determination of particular parameters is sensitive to selection of initial conditions [108]. If the initial conditions are improper, it becomes problematic to find a global minimum of the residual sum of squares for parameters in a multidimensional fitting space [49,109,110]. A rational way to obtain initial conditions is by applying parameter estimates from similar tracer kinetic studies. Likewise, species and organ dependent physiological measurements found in literature can be used to define the range for parameter boundaries. If no initial conditions are available simulation or phantom studies can be used to determine approximate values that can be used for model optimization. In addition, a number of linearizing methods can be applied to reduce computational time at the cost of limited model parameter as output [50]. Basis function and generalized linear least squares method are other options that reduce the processing time of parameter estimation compared to nonlinear least-squares approach [59,111].

The input function has great impact on the model performance, and robust determination is crucial for the accuracy of parameter calculation [112,113]. The input function is defined as blood time active concentration and can be obtained either by blood sampling or noninvasively from the left ventricle or large vessels by an image derived approach [89,113,114]. When using arterial blood sampling the input function should be corrected for dispersion and delay. On the other hand, for the non-invasive method a number of artifacts such as partial volume effect and respiratory movements can lead to misinterpretation [115]. Additionally, correction for plasma binding and metabolites should be considered.

Besides the technical aspects of kinetic modeling of dynamic PET data there are also factors more specific related to hypoxia imaging that needs to be considered. The hypoxia tracers that have been applied in dynamic PET imaging are lipophilic compounds that enter cells by free diffusion, become metabolized and consequently trapped within the cell. Based on the proposed trapping mechanisms of used hypoxia-specific tracers it is therefore reasonable to assume that they will be unable to leave the cell for the duration of the PET acquisition. On this basis, an irreversible model will be most suitable to reflect tracer accumulation in vivo. However, in studies comparing different compartment models for FAZA PET the difference between reversible and irreversible two compartment models were negligible [88,89]. Importantly, recent studies have suggested that Cu-ATSM accumulation can perhaps be influenced by copper metabolism and that there can also be an efflux of Cu-ATSM or the radioactive copper from cells [116,117], which should be kept in mind when applying kinetic models to dynamic Cu-ATSM PET data.

The majority of studies on kinetic modeling of hypoxia PET tracers are focused on cancer. As previously mentioned perfusion limited (acute) hypoxia is caused by changes in local tumor blood flow, and regional oxygenation can therefore suddenly change. These fluctuations represent a challenge, as the estimated parameters could be average values of varying oxygenation during the dynamic PET acquisition. In order to implement the use of kinetic models in clinic, the reproducibility of model output is an important part of the validation process. The reproducibility of model parameters derived from dynamic 18F-FMISO PET has been investigated and some degree of variations was observed [66]. However, part of this variation could be due to the fluctuating nature of acute hypoxia that influence tracer uptake and potentially also impact model parameters. Moreover, because hypoxia is a heterogeneous phenomenon with microregional differences in oxygen tension within a target tissue. This represents a challenge for quantification of PET imaging as uptake in a VOI will represent an average value with contribution from multiple microregions. This will also be reflected in the parameters estimated based on TACs generated from these VOIs. As an alternative, voxel-based tracer kinetic modeling can be applied and more precisely reflects the tracer behavior in smaller subvolumes [70,118]. However, computation time for this approach is demanding, and the error scale will be much higher, compared to parameters calculated based on TACs derived from larger VOIs. Therefore it is important to get a reasonable balance between the signal to noise ratio and the definition of voxel size and frame duration. Increasing the injected dose can be a way to improve the signal to noise ratio but this will also increase the absorbed dose and should therefore be considered with caution.

Conclusion and future perspectives

Dynamic PET based kinetic modeling represents a methodology that can potentially be used to extract additional information of cellular processes. Despite some promising results, a number of technical difficulties and limitations need to be solved for clinical implementation, e.g. the limited field of view in clinical PET scanners, and development of methods for robust determination of the input function without continuous blood sampling. Several studies have shown that it is possible to obtain kinetic parameters from dynamic hypoxia PET data but at present validation of model output against other modalities is sparse. This review points out the potential applications of dynamic hypoxia PET imaging but before a kinetic model can be fully integrated in the clinic it needs to be validated and shown that it contributes to the current assessment routine.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Hockel M, Vaupel P. Tumor hypoxia: definitions and current clinical, biologic, and molecular aspects. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:266–276. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.4.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vaupel P, Harrison L. Tumor hypoxia: causative factors, compensatory mechanisms, and cellular response. Oncologist. 2004;9(Suppl 5):4–9. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.9-90005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hockel M, Schlenger K, Mitze M, Schaffer U, Vaupel P. Hypoxia and Radiation Response in Human Tumors. Semin Radiat Oncol. 1996;6:3–9. doi: 10.1053/SRAO0060003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brizel DM, Sibley GS, Prosnitz LR, Scher RL, Dewhirst MW. Tumor hypoxia adversely affects the prognosis of carcinoma of the head and neck. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;38:285–289. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(97)00101-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nordsmark M, Hoyer M, Keller J, Nielsen OS, Jensen OM, Overgaard J. The relationship between tumor oxygenation and cell proliferation in human soft tissue sarcomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996;35:701–708. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(96)00132-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gray LH, Conger AD, Ebert M, Hornsey S, Scott OC. The concentration of oxygen dissolved in tissues at the time of irradiation as a factor in radiotherapy. Br J Radiol. 1953;26:638–648. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-26-312-638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brizel DM, Dodge RK, Clough RW, Dewhirst MW. Oxygenation of head and neck cancer: changes during radiotherapy and impact on treatment outcome. Radiother Oncol. 1999;53:113–117. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(99)00102-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang SC, Williams BA, Krivokapich J, Araujo L, Phelps ME, Schelbert HR. Rabbit myocardial 82Rb kinetics and a compartmental model for blood flow estimation. Am J Physiol. 1989;256:H1156–1164. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.256.4.H1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tredan O, Galmarini CM, Patel K, Tannock IF. Drug resistance and the solid tumor microenvironment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1441–1454. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skov KA, MacPhail S. Low concentrations of nitroimidazoles: effective radiosensitizers at low doses. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1994;29:87–93. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(94)90230-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee DJ, Moini M, Giuliano J, Westra WH. Hypoxic sensitizer and cytotoxin for head and neck cancer. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1996;25:397–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaanders JH, Bussink J, van der Kogel AJ. ARCON: a novel biology-based approach in radiotherapy. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3:728–737. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(02)00929-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jonathan RA, Wijffels KI, Peeters W, de Wilde PC, Marres HA, Merkx MA, Oosterwijk E, van der Kogel AJ, Kaanders JH. The prognostic value of endogenous hypoxia-related markers for head and neck squamous cell carcinomas treated with ARCON. Radiother Oncol. 2006;79:288–297. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernier J, Denekamp J, Rojas A, Trovo M, Horiot JC, Hamers H, Antognoni P, Dahl O, Richaud P, Kaanders J, van Glabbeke M, Pierart M. ARCON: accelerated radiotherapy with carbogen and nicotinamide in non small cell lung cancer: a phase I/II study by the EORTC. Radiother Oncol. 1999;52:149–156. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(99)00106-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loeffler JS, Durante M. Charged particle therapy--optimization, challenges and future directions. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10:411–424. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brurberg KG, Thuen M, Ruud EB, Rofstad EK. Fluctuations in pO2 in irradiated human melanoma xenografts. Radiat Res. 2006;165:16–25. doi: 10.1667/rr3491.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brurberg KG, Skogmo HK, Graff BA, Olsen DR, Rofstad EK. Fluctuations in pO2 in poorly and well-oxygenated spontaneous canine tumors before and during fractionated radiation therapy. Radiother Oncol. 2005;77:220–226. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vaupel P, Schlenger K, Knoop C, Hockel M. Oxygenation of human tumors: evaluation of tissue oxygen distribution in breast cancers by computerized O2 tension measurements. Cancer Res. 1991;51:3316–3322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brizel DM, Scully SP, Harrelson JM, Layfield LJ, Bean JM, Prosnitz LR, Dewhirst MW. Tumor oxygenation predicts for the likelihood of distant metastases in human soft tissue sarcoma. Cancer Res. 1996;56:941–943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nordsmark M, Bentzen SM, Rudat V, Brizel D, Lartigau E, Stadler P, Becker A, Adam M, Molls M, Dunst J, Terris DJ, Overgaard J. Prognostic value of tumor oxygenation in 397 head and neck tumors after primary radiation therapy. An international multi-center study. Radiother Oncol. 2005;77:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2005.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Griffiths JR, Robinson SP. The OxyLite: a fibre-optic oxygen sensor. Br J Radiol. 1999;72:627–630. doi: 10.1259/bjr.72.859.10624317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tran LB, Bol A, Labar D, Jordan B, Magat J, Mignion L, Gregoire V, Gallez B. Hypoxia imaging with the nitroimidazole 18F-FAZA PET tracer: a comparison with OxyLite, EPR oximetry and 19F-MRI relaxometry. Radiother Oncol. 2012;105:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bartlett RM, Beattie BJ, Naryanan M, Georgi JC, Chen Q, Carlin SD, Roble G, Zanzonico PB, Gonen M, O’Donoghue J, Fischer A, Humm JL. Image-guided PO2 probe measurements correlated with parametric images derived from 18F-fluoromisonidazole small-animal PET data in rats. J Nucl Med. 2012;53:1608–1615. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.103523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kizaka-Kondoh S, Konse-Nagasawa H. Significance of nitroimidazole compounds and hypoxia-inducible factor-1 for imaging tumor hypoxia. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:1366–1373. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01195.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muzic RF Jr, Christian BT. Evaluation of objective functions for estimation of kinetic parameters. Med Phys. 2006;33:342–353. doi: 10.1118/1.2135907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nitzsche EU, Choi Y, Czernin J, Hoh CK, Huang SC, Schelbert HR. Noninvasive quantification of myocardial blood flow in humans. A direct comparison of the [13N] ammonia and the [15O] water techniques. Circulation. 1996;93:2000–2006. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.11.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rijpkema M, Schuuring J, Bernsen PL, Bernsen HJ, Kaanders JH, van der Kogel AJ, Heerschap A. BOLD MRI response to hypercapnic hyperoxia in patients with meningiomas: correlation with Gadolinium-DTPA uptake rate. Magn Reson Imaging. 2004;22:761–767. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2004.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Remmele S, Dahnke H, Flacke S, Soehle M, Wenningmann I, Kovacs A, Traber F, Muller A, Willinek WA, Konig R, Clusmann H, Gieseke J, Schild HH, Murtz P. Quantification of the magnetic resonance signal response to dynamic (C)O(2)-enhanced imaging in the brain at 3 T: R*(2) BOLD vs. balanced SSFP. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2010;31:1300–1310. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yasui H, Matsumoto S, Devasahayam N, Munasinghe JP, Choudhuri R, Saito K, Subramanian S, Mitchell JB, Krishna MC. Low-field magnetic resonance imaging to visualize chronic and cycling hypoxia in tumor-bearing mice. Cancer Res. 2010;70:6427–6436. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bobko AA, Dhimitruka I, Eubank TD, Marsh CB, Zweier JL, Khramtsov VV. Trityl-based EPR probe with enhanced sensitivity to oxygen. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47:654–658. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reivich M, Kuhl D, Wolf A, Greenberg J, Phelps M, Ido T, Casella V, Fowler J, Gallagher B, Hoffman E, Alavi A, Sokoloff L. Measurement of local cerebral glucose metabolism in man with 18F-2-fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 1977;64:190–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bomanji JB, Costa DC, Ell PJ. Clinical role of positron emission tomography in oncology. Lancet Oncol. 2001;2:157–164. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(00)00257-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang GL, Jiang BH, Rue EA, Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS heterodimer regulated by cellular O2 tension. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:5510–5514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zimny M, Gagel B, DiMartino E, Hamacher K, Coenen HH, Westhofen M, Eble M, Buell U, Reinartz P. FDG--a marker of tumour hypoxia? A comparison with [18F] fluoromisonidazole and pO2-polarography in metastatic head and neck cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2006;33:1426–1431. doi: 10.1007/s00259-006-0175-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cherk MH, Foo SS, Poon AM, Knight SR, Murone C, Papenfuss AT, Sachinidis JI, Saunder TH, O’Keefe GJ, Scott AM. Lack of correlation of hypoxic cell fraction and angiogenesis with glucose metabolic rate in non-small cell lung cancer assessed by 18F-Fluoromisonidazole and 18F-FDG PET. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:1921–1926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dierckx RA, Van de Wiele C. FDG uptake, a surrogate of tumour hypoxia? Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35:1544–1549. doi: 10.1007/s00259-008-0758-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gagel B, Reinartz P, Dimartino E, Zimny M, Pinkawa M, Maneschi P, Stanzel S, Hamacher K, Coenen HH, Westhofen M, Bull U, Eble MJ. pO(2) Polarography versus positron emission tomography ([(18)F] fluoromisonidazole, [(18)F] -2-fluoro-2’-deoxyglucose). An appraisal of radiotherapeutically relevant hypoxia. Strahlenther Onkol. 2004;180:616–622. doi: 10.1007/s00066-004-1229-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bentzen L, Keiding S, Horsman MR, Falborg L, Hansen SB, Overgaard J. Feasibility of detecting hypoxia in experimental mouse tumours with 18F-fluorinated tracers and positron emission tomography--a study evaluating [18F] Fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose. Acta Oncol. 2000;39:629–637. doi: 10.1080/028418600750013320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pugachev A, Ruan S, Carlin S, Larson SM, Campa J, Ling CC, Humm JL. Dependence of FDG uptake on tumor microenvironment. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;62:545–553. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Willemsen AT, van den Hoff J. Fundamentals of quantitative PET data analysis. Curr Pharm Des. 2002;8:1513–1526. doi: 10.2174/1381612023394359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eschmann SM, Paulsen F, Reimold M, Dittmann H, Welz S, Reischl G, Machulla HJ, Bares R. Prognostic impact of hypoxia imaging with 18F-misonidazole PET in non-small cell lung cancer and head and neck cancer before radiotherapy. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:253–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thorwarth D, Eschmann SM, Scheiderbauer J, Paulsen F, Alber M. Kinetic analysis of dynamic 18F-fluoromisonidazole PET correlates with radiation treatment outcome in head-and-neck cancer. BMC Cancer. 2005;5:152. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-5-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gunn RN, Gunn SR, Turkheimer FE, Aston JA, Cunningham VJ. Positron emission tomography compartmental models: a basis pursuit strategy for kinetic modeling. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:1425–1439. doi: 10.1097/01.wcb.0000045042.03034.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dolbier WR Jr, Li AR, Koch CJ, Shiue CY, Kachur AV. [18F] -EF5, a marker for PET detection of hypoxia: synthesis of precursor and a new fluorination procedure. Appl Radiat Isot. 2001;54:73–80. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8043(00)00102-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rijpkema M, Kaanders JH, Joosten FB, van der Kogel AJ, Heerschap A. Method for quantitative mapping of dynamic MRI contrast agent uptake in human tumors. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2001;14:457–463. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tofts PS, Brix G, Buckley DL, Evelhoch JL, Henderson E, Knopp MV, Larsson HB, Lee TY, Mayr NA, Parker GJ, Port RE, Taylor J, Weisskoff RM. Estimating kinetic parameters from dynamic contrast-enhanced T(1)-weighted MRI of a diffusable tracer: standardized quantities and symbols. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1999;10:223–232. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2586(199909)10:3<223::aid-jmri2>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Phelps M. PET: Molecular Imaging and Its Biological Applications. New York: Springer; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takesh M. The Potential Benefit by Application of Kinetic Analysis of PET in the Clinical Oncology. ISRN Oncol. 2012;2012:349351. doi: 10.5402/2012/349351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kadrmas DJ, Oktay MB. Generalized separable parameter space techniques for fitting 1K-5K serial compartment models. Med Phys. 2013;40:072502. doi: 10.1118/1.4810937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Logan J, Fowler JS, Volkow ND, Wolf AP, Dewey SL, Schlyer DJ, MacGregor RR, Hitzemann R, Bendriem B, Gatley SJ, et al. Graphical analysis of reversible radioligand binding from time-activity measurements applied to [N-11C-methyl] -(-)-cocaine PET studies in human subjects. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1990;10:740–747. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1990.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kaanders JH, Wijffels KI, Marres HA, Ljungkvist AS, Pop LA, van den Hoogen FJ, de Wilde PC, Bussink J, Raleigh JA, van der Kogel AJ. Pimonidazole binding and tumor vascularity predict for treatment outcome in head and neck cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62:7066–7074. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Olive PL, Durand RE, Raleigh JA, Luo C, Aquino-Parsons C. Comparison between the comet assay and pimonidazole binding for measuring tumour hypoxia. Br J Cancer. 2000;83:1525–1531. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Raleigh JA, Chou SC, Arteel GE, Horsman MR. Comparisons among pimonidazole binding, oxygen electrode measurements, and radiation response in C3H mouse tumors. Radiat Res. 1999;151:580–589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chang Q, Jurisica I, Do T, Hedley DW. Hypoxia predicts aggressive growth and spontaneous metastasis formation from orthotopically grown primary xenografts of human pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71:3110–3120. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Andreyev A, Celler A. Dual-isotope PET using positron-gamma emitters. Phys Med Biol. 2011;56:4539–4556. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/56/14/020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chapman JD, Baer K, Lee J. Characteristics of the metabolism-induced binding of misonidazole to hypoxic mammalian cells. Cancer Res. 1983;43:1523–1528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chapman JD, Franko AJ, Sharplin J. A marker for hypoxic cells in tumours with potential clinical applicability. Br J Cancer. 1981;43:546–550. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1981.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rasey JS, Koh WJ, Grierson JR, Grunbaum Z, Krohn KA. Radiolabelled fluoromisonidazole as an imaging agent for tumor hypoxia. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1989;17:985–991. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(89)90146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Boellaard R, Knaapen P, Rijbroek A, Luurtsema GJ, Lammertsma AA. Evaluation of basis function and linear least squares methods for generating parametric blood flow images using 15O-water and Positron Emission Tomography. Mol Imaging Biol. 2005;7:273–285. doi: 10.1007/s11307-005-0007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Valk PE, Mathis CA, Prados MD, Gilbert JC, Budinger TF. Hypoxia in human gliomas: demonstration by PET with fluorine-18-fluoromisonidazole. J Nucl Med. 1992;33:2133–2137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Spence AM, Muzi M, Swanson KR, O’Sullivan F, Rockhill JK, Rajendran JG, Adamsen TC, Link JM, Swanson PE, Yagle KJ, Rostomily RC, Silbergeld DL, Krohn KA. Regional hypoxia in glioblastoma multiforme quantified with [18F] fluoromisonidazole positron emission tomography before radiotherapy: correlation with time to progression and survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:2623–2630. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bentzen L, Keiding S, Nordsmark M, Falborg L, Hansen SB, Keller J, Nielsen OS, Overgaard J. Tumour oxygenation assessed by 18F-fluoromisonidazole PET and polarographic needle electrodes in human soft tissue tumours. Radiother Oncol. 2003;67:339–344. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(03)00081-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rasey JS, Casciari JJ, Hofstrand PD, Muzi M, Graham MM, Chin LK. Determining hypoxic fraction in a rat glioma by uptake of radiolabeled fluoromisonidazole. Radiat Res. 2000;153:84–92. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2000)153[0084:dhfiar]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Casciari JJ, Graham MM, Rasey JS. A modeling approach for quantifying tumor hypoxia with [F-18] fluoromisonidazole PET time-activity data. Med Phys. 1995;22:1127–1139. doi: 10.1118/1.597506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kelly CJ, Brady M. A model to simulate tumour oxygenation and dynamic [18F] -Fmiso PET data. Phys Med Biol. 2006;51:5859–5873. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/51/22/009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Whisenant JG, Peterson TE, Fluckiger JU, Tantawy MN, Ayers GD, Yankeelov TE. Reproducibility of static and dynamic (18)F-FDG, (18)F-FLT, and (18)F-FMISO MicroPET studies in a murine model of HER2+ breast cancer. Mol Imaging Biol. 2013;15:87–96. doi: 10.1007/s11307-012-0564-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bejot R, Kersemans V, Kelly C, Carroll L, King RC, Gouverneur V, Elizarov AM, Ball C, Zhang J, Miraghaie R, Kolb HC, Smart S, Hill S. Pre-clinical evaluation of a 3-nitro-1,2,4-triazole analogue of [18F] FMISO as hypoxia-selective tracer for PET. Nucl Med Biol. 2010;37:565–575. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bruehlmeier M, Roelcke U, Schubiger PA, Ametamey SM. Assessment of hypoxia and perfusion in human brain tumors using PET with 18F-fluoromisonidazole and 15O-H2O. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:1851–1859. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bruehlmeier M, Kaser-Hotz B, Achermann R, Bley CR, Wergin M, Schubiger PA, Ametamey SM. Measurement of tumor hypoxia in spontaneous canine sarcomas. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2005;46:348–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.2005.00065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Thorwarth D, Eschmann SM, Paulsen F, Alber M. A kinetic model for dynamic [18F] -Fmiso PET data to analyse tumour hypoxia. Phys Med Biol. 2005;50:2209–2224. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/50/10/002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cho H, Ackerstaff E, Carlin S, Lupu ME, Wang Y, Rizwan A, O’Donoghue J, Ling CC, Humm JL, Zanzonico PB, Koutcher JA. Noninvasive multimodality imaging of the tumor microenvironment: registered dynamic magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography studies of a preclinical tumor model of tumor hypoxia. Neoplasia. 2009;11:247–259. doi: 10.1593/neo.81360. 242p following 259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang W, Georgi JC, Nehmeh SA, Narayanan M, Paulus T, Bal M, O’Donoghue J, Zanzonico PB, Schmidtlein CR, Lee NY, Humm JL. Evaluation of a compartmental model for estimating tumor hypoxia via FMISO dynamic PET imaging. Phys Med Biol. 2009;54:3083–3099. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/54/10/008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang W, Lee NY, Georgi JC, Narayanan M, Guillem J, Schoder H, Humm JL. Pharmacokinetic analysis of hypoxia (18)F-fluoromisonidazole dynamic PET in head and neck cancer. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:37–45. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.067009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Takasawa M, Beech JS, Fryer TD, Hong YT, Hughes JL, Igase K, Jones PS, Smith R, Aigbirhio FI, Menon DK, Clark JC, Baron JC. Imaging of brain hypoxia in permanent and temporary middle cerebral artery occlusion in the rat using 18F-fluoromisonidazole and positron emission tomography: a pilot study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:679–689. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hong YT, Beech JS, Smith R, Baron JC, Fryer TD. Parametric mapping of [18F] fluoromisonidazole positron emission tomography using basis functions. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2011;31:648–657. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nunn A, Linder K, Strauss HW. Nitroimidazoles and imaging hypoxia. Eur J Nucl Med. 1995;22:265–280. doi: 10.1007/BF01081524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yang DJ, Wallace S, Cherif A, Li C, Gretzer MB, Kim EE, Podoloff DA. Development of F-18-labeled fluoroerythronitroimidazole as a PET agent for imaging tumor hypoxia. Radiology. 1995;194:795–800. doi: 10.1148/radiology.194.3.7862981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.van Loon J, Janssen MH, Ollers M, Aerts HJ, Dubois L, Hochstenbag M, Dingemans AM, Lalisang R, Brans B, Windhorst B, van Dongen GA, Kolb H, Zhang J, De Ruysscher D, Lambin P. PET imaging of hypoxia using [18F] HX4: a phase I trial. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37:1663–1668. doi: 10.1007/s00259-010-1437-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Vercellino L, Groheux D, Thoury A, Delord M, Schlageter MH, Delpech Y, Barre E, Baruch-Hennequin V, Tylski P, Homyrda L, Walker F, Barranger E, Hindie E. Hypoxia imaging of uterine cervix carcinoma with (18)F-FETNIM PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2012;37:1065–1068. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e3182638e7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lehtio K, Oikonen V, Nyman S, Gronroos T, Roivainen A, Eskola O, Minn H. Quantifying tumour hypoxia with fluorine-18 fluoroerythronitroimidazole ([18F] FETNIM) and PET using the tumour to plasma ratio. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2003;30:101–108. doi: 10.1007/s00259-002-1016-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lehtio K, Oikonen V, Gronroos T, Eskola O, Kalliokoski K, Bergman J, Solin O, Grenman R, Nuutila P, Minn H. Imaging of blood flow and hypoxia in head and neck cancer: initial evaluation with [(15)O] H(2)O and [(18)F] fluoroerythronitroimidazole PET. J Nucl Med. 2001;42:1643–1652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kumar P, Wiebe LI, Asikoglu M, Tandon M, McEwan AJ. Microwave-assisted (radio)halogenation of nitroimidazole-based hypoxia markers. Appl Radiat Isot. 2002;57:697–703. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8043(02)00185-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Piert M, Machulla HJ, Picchio M, Reischl G, Ziegler S, Kumar P, Wester HJ, Beck R, McEwan AJ, Wiebe LI, Schwaiger M. Hypoxia-specific tumor imaging with 18F-fluoroazomycin arabinoside. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:106–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sorger D, Patt M, Kumar P, Wiebe LI, Barthel H, Seese A, Dannenberg C, Tannapfel A, Kluge R, Sabri O. [18F] Fluoroazomycinarabinofuranoside (18FAZA) and [18F] Fluoromisonidazole (18FMISO): a comparative study of their selective uptake in hypoxic cells and PET imaging in experimental rat tumors. Nucl Med Biol. 2003;30:317–326. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(02)00442-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Postema EJ, McEwan AJ, Riauka TA, Kumar P, Richmond DA, Abrams DN, Wiebe LI. Initial results of hypoxia imaging using 1-alpha-D: -(5-deoxy-5-[18F] -fluoroarabinofuranosyl)-2-nitroimidazole (18F-FAZA) Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009;36:1565–1573. doi: 10.1007/s00259-009-1154-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Reischl G, Dorow DS, Cullinane C, Katsifis A, Roselt P, Binns D, Hicks RJ. Imaging of tumor hypoxia with [124I] IAZA in comparison with [18F] FMISO and [18F] FAZA--first small animal PET results. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2007;10:203–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Busk M, Munk OL, Jakobsen S, Wang T, Skals M, Steiniche T, Horsman MR, Overgaard J. Assessing hypoxia in animal tumor models based on pharmocokinetic analysis of dynamic FAZA PET. Acta Oncol. 2010;49:922–933. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2010.503970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shi K, Souvatzoglou M, Astner ST, Vaupel P, Nusslin F, Wilkens JJ, Ziegler SI. Quantitative assessment of hypoxia kinetic models by a cross-study of dynamic 18F-FAZA and 15O-H2O in patients with head and neck tumors. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:1386–1394. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.074336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Verwer EE, van Velden FH, Bahce I, Yaqub M, Schuit RC, Windhorst AD, Raijmakers P, Lammertsma AA, Smit EF, Boellaard R. Pharmacokinetic analysis of [18F] FAZA in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;40:1523–1531. doi: 10.1007/s00259-013-2462-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Fujibayashi Y, Taniuchi H, Yonekura Y, Ohtani H, Konishi J, Yokoyama A. Copper-62-ATSM: a new hypoxia imaging agent with high membrane permeability and low redox potential. J Nucl Med. 1997;38:1155–1160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dehdashti F, Mintun MA, Lewis JS, Bradley J, Govindan R, Laforest R, Welch MJ, Siegel BA. In vivo assessment of tumor hypoxia in lung cancer with 60Cu-ATSM. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2003;30:844–850. doi: 10.1007/s00259-003-1130-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dehdashti F, Grigsby PW, Lewis JS, Laforest R, Siegel BA, Welch MJ. Assessing tumor hypoxia in cervical cancer by PET with 60Cu-labeled diacetyl-bis(N4-methylthiosemicarbazone) J Nucl Med. 2008;49:201–205. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.048520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dietz DW, Dehdashti F, Grigsby PW, Malyapa RS, Myerson RJ, Picus J, Ritter J, Lewis JS, Welch MJ, Siegel BA. Tumor hypoxia detected by positron emission tomography with 60Cu-ATSM as a predictor of response and survival in patients undergoing Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for rectal carcinoma: a pilot study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:1641–1648. doi: 10.1007/s10350-008-9420-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yuan H, Schroeder T, Bowsher JE, Hedlund LW, Wong T, Dewhirst MW. Intertumoral differences in hypoxia selectivity of the PET imaging agent 64Cu(II)-diacetyl-bis(N4-methylthiosemicarbazone) J Nucl Med. 2006;47:989–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.O’Donoghue JA, Zanzonico P, Pugachev A, Wen B, Smith-Jones P, Cai S, Burnazi E, Finn RD, Burgman P, Ruan S, Lewis JS, Welch MJ, Ling CC, Humm JL. Assessment of regional tumor hypoxia using 18F-fluoromisonidazole and 64Cu(II)-diacetyl-bis(N4-methylthiosemicarbazone) positron emission tomography: Comparative study featuring microPET imaging, Po2 probe measurement, autoradiography, and fluorescent microscopy in the R3327-AT and FaDu rat tumor models. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;61:1493–1502. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.12.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lewis JS, McCarthy DW, McCarthy TJ, Fujibayashi Y, Welch MJ. Evaluation of 64Cu-ATSM in vitro and in vivo in a hypoxic tumor model. J Nucl Med. 1999;40:177–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lewis JS, Herrero P, Sharp TL, Engelbach JA, Fujibayashi Y, Laforest R, Kovacs A, Gropler RJ, Welch MJ. Delineation of hypoxia in canine myocardium using PET and copper(II)-diacetyl-bis(N(4)-methylthiosemicarbazone) J Nucl Med. 2002;43:1557–1569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Dearling JL, Packard AB. Some thoughts on the mechanism of cellular trapping of Cu(II)-ATSM. Nucl Med Biol. 2010;37:237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Burgman P, O’Donoghue JA, Lewis JS, Welch MJ, Humm JL, Ling CC. Cell line-dependent differences in uptake and retention of the hypoxia-selective nuclear imaging agent Cu-ATSM. Nucl Med Biol. 2005;32:623–630. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Holland JP, Giansiracusa JH, Bell SG, Wong LL, Dilworth JR. In vitro kinetic studies on the mechanism of oxygen-dependent cellular uptake of copper radiopharmaceuticals. Phys Med Biol. 2009;54:2103–2119. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/54/7/017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bowen SR, van der Kogel AJ, Nordsmark M, Bentzen SM, Jeraj R. Characterization of positron emission tomography hypoxia tracer uptake and tissue oxygenation via electrochemical modeling. Nucl Med Biol. 2011;38:771–780. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Dalah E, Bradley D, Nisbet A. Simulation of tissue activity curves of (64)Cu-ATSM for sub-target volume delineation in radiotherapy. Phys Med Biol. 2010;55:681–694. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/55/3/009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.McCall KC, Humm JL, Bartlett R, Reese M, Carlin S. Copper-64-diacetyl-bis(N(4)-methylthiosemicarbazone) pharmacokinetics in FaDu xenograft tumors and correlation with microscopic markers of hypoxia. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;84:e393–399. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rust TC, Kadrmas DJ. Rapid dual-tracer PTSM+ATSM PET imaging of tumour blood flow and hypoxia: a simulation study. Phys Med Biol. 2006;51:61–75. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/51/1/005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Black NF, McJames S, Rust TC, Kadrmas DJ. Evaluation of rapid dual-tracer (62)Cu-PTSM + (62)Cu-ATSM PET in dogs with spontaneously occurring tumors. Phys Med Biol. 2008;53:217–232. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/53/1/015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Black NF, McJames S, Kadrmas DJ. Rapid Multi-Tracer PET Tumor Imaging With F-FDG and Secondary Shorter-Lived Tracers. IEEE Trans Nucl Sci. 2009;56:2750–2758. doi: 10.1109/TNS.2009.2026417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ikoma Y, Watabe H, Shidahara M, Naganawa M, Kimura Y. PET kinetic analysis: error consideration of quantitative analysis in dynamic studies. Ann Nucl Med. 2008;22:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s12149-007-0083-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wu FX, Mu L. Parameter estimation in rational models of molecular biological systems. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2009;2009:3263–3266. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2009.5333508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Luenberger D. Optimization by vector space methods. New York: Wiley; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Marquardt D. An algorithm for least squares estimation of nonlinear parameters. SIAM J Soc Ind Appl Math. 1963;11:431–441. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Dai X, Chen Z, Tian J. Performance evaluation of kinetic parameter estimation methods in dynamic FDG-PET studies. Nucl Med Commun. 2011;32:4–16. doi: 10.1097/mnm.0b013e32833f6c05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Croteau E, Lavallee E, Labbe SM, Hubert L, Pifferi F, Rousseau JA, Cunnane SC, Carpentier AC, Lecomte R, Benard F. Image-derived input function in dynamic human PET/CT: methodology and validation with 11C-acetate and 18F-fluorothioheptadecanoic acid in muscle and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose in brain. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37:1539–1550. doi: 10.1007/s00259-010-1443-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Fang YH, Muzic RF Jr. Spillover and partial-volume correction for image-derived input functions for small-animal 18F-FDG PET studies. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:606–614. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.047613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Laforest R, Sharp TL, Engelbach JA, Fettig NM, Herrero P, Kim J, Lewis JS, Rowland DJ, Tai YC, Welch MJ. Measurement of input functions in rodents: challenges and solutions. Nucl Med Biol. 2005;32:679–685. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2005.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Zanotti-Fregonara P, Chen K, Liow JS, Fujita M, Innis RB. Image-derived input function for brain PET studies: many challenges and few opportunities. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2011;31:1986–1998. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Hueting R, Kersemans V, Cornelissen B, Tredwell M, Hussien K, Christlieb M, Gee AD, Passchier J, Smart SC, Dilworth JR, Gouverneur V, Muschel RJ. A comparison of the behavior of (64)Cu-acetate and (64)Cu-ATSM in vitro and in vivo. J Nucl Med. 2014;55:128–134. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.119917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Liu J, Hajibeigi A, Ren G, Lin M, Siyambalapitiyage W, Liu Z, Simpson E, Parkey RW, Sun X, Oz OK. Retention of the radiotracers 64Cu-ATSM and 64Cu-PTSM in human and murine tumors is influenced by MDR1 protein expression. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:1332–1339. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.061879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.El Fakhri G, Sitek A, Guerin B, Kijewski MF, Di Carli MF, Moore SC. Quantitative dynamic cardiac 82Rb PET using generalized factor and compartment analyses. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:1264–1271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]