Abstract

Background and Aims:

Elderly subjects have a dysregulation of immune response mainly due to the changes in cell - mediated immunity. Due to their weakened immune response, the elderly are at increased risk of infection and related complications. In Unani medicine Tiryaq wabai was used for the prevention of epidemic diseases during outbreaks, but it has not been explored scientifically so far. The study was aimed to evaluate the immune-stimulating effect of Tiryaq wabai in elderly.

Materials and Methods:

A randomized placebo controlled trial was conducted at National Institute of Unani Medicine Hospital, Bangalore. Thirty immunocompromised elderly persons were selected on the basis of clinical examination considering parameters like history of recurrent infection, unexplained weight loss, persistent diarrhea etc. They were randomly assigned, 20 in test and 10 in the control group. Tiryaq wabai was given to test group 500 mg orally thrice in a week for 45 days. Placebo was given orally to the control group at a dose of 500 mg thrice in a week for 45 days. Response was assessed by total leucocyte count (TLC), lymphocyte percentage, absolute lymphocyte count (ALC), CD4 and CD8 count. The results were analyzed statistically using Graph Pad InStat 3.

Results:

The test drug showed statistically significant increase in TLC (P < 0.001), lymphocyte percentage (P < 0.001),ALC (P < 0.001), CD4 count (P < 0.001) in comparison to control group, but increase in CD8 count was not statistically significant. No major adverse effect was observed throughout the study.

Conclusion:

The findings outlined above indicate immune- stimulating activity of Tiryaq wabai and supports its use in conditions where immunostimulation is required and thus is suggestive of therapeutic usefulness.

KEY WORDS: Aging, immune-senescence, T-lymphocytes, Unani medicine

INTRODUCTION

Aging is a process of bodily change with time, leading to increased susceptibility to disease, and ultimately to death. This is reflected in the rise in age specific death rates in the population. After the age of 30 years, gradually there are structural and functional changes in the body. By the age of 50-60 years these changes get manifested clinically like decreased energy, vision, memory, locomotion or exertional dyspnea, reduction in homeostasis and immunity.[1] Of 6 billion people in the world 600 million are elderly and are expected to increase to >1.2 billion by 2025.[2] In India, the population of elderly has risen from 6.5% in 1991 to 7.7% in 2001 and will be 12% in 2025.[3] With advances in modern medical research techniques, research on age-related illnesses has become intense. Various biological therapies have been introduced in biotechnology and biopharmaceutical sectors for altered immune functions in elderly such as monoclonal antibodies, interferon, interleukins, several types of colony stimulating factors, restoration of the thymus, telomerase gene therapy. Many of these therapies have side-effects such as chills, fever, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.[4]

The process of aging is attributed mostly to the excessive oxidants produced in the body. Reactive oxidant species and immune dysfunction are major causes of age-related diseases,[5,6,7] immune-senescence, attributed partly to the reduction in number of T-lymphocytes and loss of their functions. Such loss increases the prevalence of infectious diseases in the elderly.[6,7] The maintenance of antioxidant and immune fitness is a rational approach to preventive health care. The importance of disease prevention is recognized by Unani medicine through experience accumulated over centuries. Tiryaq wabai is a well-documented and well-known drug in Unani system of medicine for its wide use for prophylaxis during epidemics of cholera, plague and other epidemic diseases. Tiryaq wabai was used by Avicenna and Galen in healthy persons as well as in patients during epidemics.[8,9] Tiryaq wabai was selected for immune-stimulating study for two reasons. First, Unani descriptions were correlated with the immune-stimulating activity, therapeutically Tiryaq wabai is indicated for prevention of epidemic diseases during epidemics. The second basis for its selection were scientific reports regarding immune modulating, and antioxidant activity or related pharmacological actions and therapeutic effects of the ingredients of this formulation. Tiryaq wabai consists of three ingredients Sibr (Aloe barbadensis), Zaafran (Crocus sativus) and Mur (Commiphora myrrh) in the ratio of 2:1:1.[9] Antioxidant and immune-stimulating effect of A. barbadensis,[10,11,12] C. myrrha[13] and C. sativus[14] has already been established in animal models.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was a randomized placebo controlled trial designed to evaluate the immunostimulating effect of Tiryaq wabai in elderly persons. After taking ethical clearance from the Institutional Ethical Committee of National Institute of Unani Medicine (NIUM) Bangalore (IEC/IV/14/TST), the study was carried out over a period of 12 months from April 2010 to March 2011 in NIUM hospital. After obtaining informed consent, 30 immunocompromised elderly persons were selected and randomly assigned into two groups, 20 in test and 10 in the control group. Test group was treated with Tiryaq wabai 500 mg 3 times a week for 45 days, while in the placebo group, roasted wheat flour was given in the dose of 500 mg 3 times a week for 45 days. Persons of either sex of ≥ 60 years with two or more signs of immunodeficiency like (i) history of recurrent infection, (ii) unexplained weight loss, (iii) persistent diarrhea, (iv) persistent thrush in mouth, (v) 2 or more months on oral antibiotics with little effect were included in the study. Persons below the age of 60 years, receiving immunosuppressive drugs, uncontrolled diabetes and hypertension, chronic obstructed pulmonary disease, ischemic heart disease were excluded from the study. The subjects were strictly advised to stick to the usual dietary habits until the completion of the study. The response was measured by the assessment of total leucocyte count (TLC) every 15th day up to 45 days and lymphocyte percentage, absolute lymphocyte count (ALC), CD4 count, CD8 count, pre- and post-treatment. Safety of the treatment was assessed by renal function test and liver function test before and after treatment. The data was analyzed by computerized statistical package Graph Pad InStat version 3 (GraphPad Software, Inc. 7825 Fay Avenue, Suite 230, La Jolla, CA 92037 USA). Analysis of variance one-way for the intra-group comparison and Tukey Kraman multiple comparison tests were used for inter-group comparison.

RESULTS

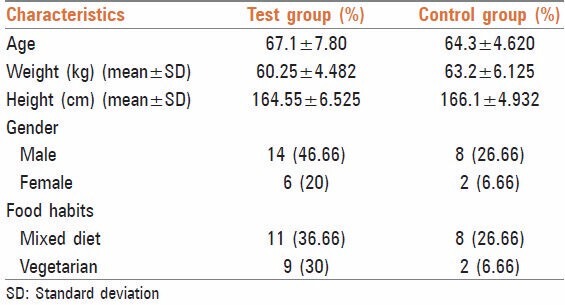

Characteristics of the subjects before the start of the trial have been presented in Table 1. Study population comprised of 73.33% males and 26.66%[8] females. About 63.34% subjects had mixed dietary habits, whereas 36.66%[11] were vegetarians.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the subjects

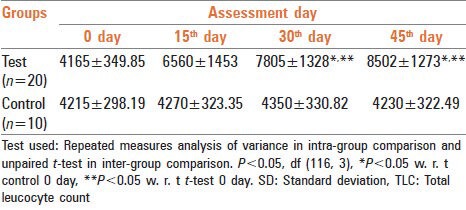

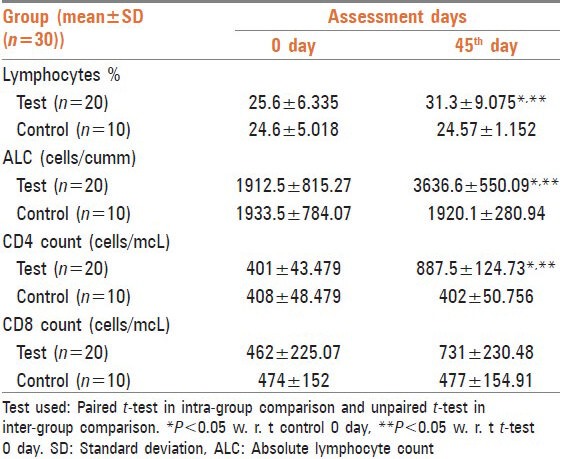

In this study, immune-stimulating effect of Tiryaq wabai was evaluated. The response was measured by the assessment of TLC every 15th day [Table 2], lymphocyte percentage, ALC, CD4 count and CD8 count before and after treatment [Table 3]. TLC, lymphocyte percentage, ALC and CD4 count showed a significant increase after treatment with respect to 0 day test and 45th day control CD8 count also showed increase, but the difference was not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Effect of Tiryaq wabai on TLC (mean±SD) in elderly persons

Table 3.

Effect of Tiryaqe wabai on lymphocytes %, ALC, CD4 count and CD8 count in elderly persons

DISCUSSION

Age associated changes in cell mediated immunity strongly depend on thymic functions. As an individual ages, the thymus undergoes a progressive involution and the output of new cells fall significantly. This results in decreased concentration of naïve T-cells in peripheral blood and lymph nodes. In the elderly, there is a decrease in the diversity and functional integrity of both CD4 and CD8 T-cell subsets, which contribute to decreased ability to respond adequately to repeated infection. Production and maintenance of the diverse peripheral T-cell repertoire are critical to the normal function of the immune system.[15] Animal studies have shown that A. barbadensis increases the proliferation of T-lymphocytes in involuted thymus. Gonzalez et al. 1990 found that newly weaned mice treated with 30 mg water extract of Aloe subcutaneously showed greater proliferation of T-lymphocytes at thymus cortex that delayed fat infiltration of the involution at that level.[16] Reynolds and Dweck 1999 and Turner 2004 found immune modulating activities of the polysaccharides in A. barbadensis and suggest that these effects occur via activation of macrophage cells to generate nitric oxide, secrete cytokines and present cell surface markers. Acemannan, a polysaccharide stimulates antigenic response of human lymphocytes as well as the formation of all types of leukocytes from both spleen and bone marrow in irradiated mice. Lectin found in Aloe acts as mitogenic factor to stimulate lymphocyte proliferation and growth. Lectin enables the cells to recognize foreign cells and to stimulate macrophages for endocytosis.[17,18]

Said found that C. myrrh significantly increases all types of leucocytes during different stages of healing. On microscopic examination of blood smear from C. myrrh treated rats with skin injury, Said found an elevated count of middle sized lymphocytes and neutrophils with well-defined nuclear lobules and rich granular cytoplasm. Furthermore, in spleen and lymph nodes, he also found an increased thickness of lymphatic sheath around the arterioles in the white pulp that was associated with high density of the medium sized lymphocytes in the secondary lymphoid follicles of the lymph nodes with engorged sinusoids.[19] C. myrrh helped to maintain the relative rise of leukocyte count throughout the healing period. Bani 2011 found that all animal models treated with alcoholic extract of C. sativus at graded dose level from 1.56 to 50 mg/kg body weight showed significant modulation of immune reactivity. Alcoholic extract of C. sativus increases Direct- type hypersensitivity reaction (DTH) in mice.[20] Increase in DTH reaction in response to antigen revealed the immune stimulatory effect of alcoholic extract of C. sativus on T-lymphocytes and accessory cell types required for expression of reaction.

In this study, increase in TLC, lymphocyte percentage, absolute lymphocytes and CD4 cell count after the use of Tiryaq wabai is supported by animal studies showing an increase in all types of leucocytes after the use of C. myrrh and A. barbadensis in separate studies. Aloe also increases proliferation of lymphocytes at thymus cortex and stimulates macrophages for endocytosis. C. sativus increases DTH reaction in mice as mentioned above. DTH reactions are mediated by T-cells and monocyte/macrophages rather than by antibodies. Delayed hypersensitivity is a major mechanism of defense against various intracellular pathogens including Mycobacteria, fungi and certain parasites.

Leukocytes are cells of the immune system involved in defending the body against both infectious disease and foreign materials. Neutrophils, basophils, and eosinophils are granulocyte leucocytes; these cells contain granules in their cytoplasm. These granules are membrane-bound enzymes that act primarily in the digestion of endocytosed particles. Neutrophils/polymorphonuclear defend against bacterial or fungal infection and other very small inflammatory processes that are usually first responders to microbial infection. Neutrophils are very active in phagocytizing bacteria. Basophils are chiefly responsible for allergic and antigen response by releasing the chemical histamine causing vasodilatation. Eosinophils deal with parasitic infections. These are also the predominant inflammatory cells in allergic reactions.[21] Monocyte and macrophages are vital to the regulation of immune responses and the development of inflammation; Macrophages function in both nonspecific defense (innate immunity) as well as specific defense mechanisms (adaptive immunity) of vertebrate animals. Their role is to phagocytose, or engulf and then digest cellular debris and pathogens, either as stationary or as mobile cells by producing powerful chemical substances (monokines) including enzymes, complement proteins, and regulatory factors such as interleukin-1. They also stimulate lymphocytes and other immune cells to respond to pathogens. They are specialized phagocytic cells that attack foreign substances, infectious microbes and cancer cells through destruction and ingestion.[22] Increased proliferation of T-lymphocytes at thymus cortex results in an increased number of naïve CD4 T-cells in peripheral blood. Naïve CD4 T-cells respond to newly encountered antigens and once activated, provide help to cognate B-cells. These interactions are essential to germinal center formation and high affinity antibody generation.[23] CD4 T-cells (helper T-cells) coordinate the immune response and play a central role in immune protection. They help B-cells to make antibodies, to induce macrophages to develop enhanced microbicidal activity, to recruit neutrophils, eosinophils, and basophils to the sites of infection and inflammation, and through production of cytokines and chemokines and to orchestrate the full panoply of immune responses.[24] Safety parameters were found within normal range before and after treatment in both groups. Thus, our drug may be considered to be safe. This study suggests that Tiryaq wabai has immunostimulating capabilities and provides direct evidence for the immunostimulating effects of Tiryaq wabai in humans.

The overall effect of the test drug was found quite encouraging in the treatment of immunocompromised elderly persons. No clinically significant side effects were observed in the test group and overall compliance to the treatment was found excellent. The findings outlined above indicate immune-stimulating activity of Unani test drug Tiryaq wabai and suggest its use in conditions where immune-stimulation is required and thus is suggestive of its therapeutic usefulness. Such plant based immune-stimulant may have application in the treatment of immunodeficiency diseases, allergic manifestation, and combinational therapy with antibiotics and as a vaccine adjuvant.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are extremely thankful to Prof. M. A. Jafri, Director, National Institute of Unani Medicine for providing basic facilities to carry out this work. We are also thankful to Dr. Ghulamuddin Sofi, Lecturer, Department of Ilmul Advia, NIUM, Bangalore for statistical analysis and Dr. Jayaram N, Pathologist, Anand Diagnostics, for his crucial contribution regarding cytometery examination not available in other laboratories.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This study was funded by National Institute of Unani Medicine, Bengaluru.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Suhami RL, Moxham J. 4th ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2004. Text Book of Medicine; pp. 183–5. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park K. 20th ed. Jabalpur: Banarsidas Bhanot; 2007. Textbook of Preventive and Social Medicine; p. 512. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar V. Geriatric medicine. In: Shah SN, editor. API Textbook of Medicine. Mumbai: API; 2003. pp. 1459–62. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fülöp T, Larbi A, Hirokawa K, Mocchegiani E, Lesourds B, Castle S, et al. Immunosupportive therapies in aging. Clin Interv Aging. 2007;2:33–54. doi: 10.2147/ciia.2007.2.1.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moskovitz J, Yim MB, Chock PB. Free radicals and disease. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2002;397:354–9. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hakim FT, Flomerfelt FA, Boyiadzis M, Gress RE. Aging, immunity and cancer. Curr Opin Immunol. 2004;16:151–6. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ko KM, Leung HY. Enhancement of ATP generation capacity, antioxidant activity and immunomodulatory activities by Chinese Yang and Yin tonifying herbs. Chin Med. 2007;2:3. doi: 10.1186/1749-8546-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ismail J. Vol. 5. New Delhi: Kitab al Shifa; 2010. Zakhira khuarzam shahi; p. 94. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kabeeruddin M. Lahore: Siddiqui Publications; 1921. Bayaze Kabeer; p. 12. 36. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moss RW. New York: Equinox Press; 1996. Cancer Therapy-The Independent Consumer Guide to Non-toxic Treatment and Prevention; pp. 126–7. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh S, P.K. Sharma N, Kumar R. Dudhe Biological activities of Aloe vera. Int J Pharm Technol. 2010;l2:259–80. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamman JH. Composition and applications of Aloe vera leaf gel. Molecules. 2008;13:1599–616. doi: 10.3390/molecules13081599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Assimopoulou AN, Zlatanos SN, Papageorgiou VP. Anti-oxidant activity of natural resins and bio-active triterpenes in oil substrates. Food Chem. 2005;92:721–7. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bakshi H, Sam S, Islam T, Singh P, Sharma M. The free radical scavenging and the lipid peroxidation inhibition of crocin isolated from Kashmiri saffron (Crocus sativus) occurring in northern part of India International Journal of PharmTech Research CODEN (USA) IJPRIF. 2009;1:1317–21. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khazen W, M’bika JP, Tomkiewicz C, Benelli C, Chany C, Achour A, et al. Expression of macrophage-selective markers in human and rodent adipocytes. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:5631–4. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haffor AS. Effect of Commiphora molmol on leukocytes proliferation in relation to histological alterations before and during healing from injury. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2010;17:139–46. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steinmann GG. Changes in the human thymus during aging. Curr Top Pathol. 1986;75:43–88. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-82480-7_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tte. Cor. Mario González-Quevedo Rodríguez, Dr. Gonzalo Abín Montalván, Dr. Nelson Merino García, Lic José de la Paz Naranjo Lic. Miguel Alonso González Effect of Aloe barbadensis on the thymus gland involution of mice. Rev Club Med Mil. 1990;28:88–92. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reynolds T, Dweck AC. Aloe vera leaf gel: A review update. J Ethnopharmacol. 1999;68:3–37. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(99)00085-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turner CE, Williamson DA, Stroud PA, Talley DJ. Evaluation and comparison of commercially available Aloe vera L. products using size exclusion chromatography with refractive index and multi-angle laser light scattering detection. Int Immunopharmacol. 2004;4:1727–37. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bani S, Pandey A, Agnihotri VK, Pathania V, Singh B. Selective Th2 upregulation by Crocus sativus: A neutraceutical spice. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2011. 2011:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2011/639862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gartner LP, Hiatt JL. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2007. Color Textbook of Histology; p. 225. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lefebvre JS, Haynes L. Aging of the CD4 T-cell compartment. Open Longev Sci. 2012;6:83–91. doi: 10.2174/1876326X01206010083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu J, Paul WE. CD4 T-cells: Fates, functions, and faults. Blood. 2008;112:1557–69. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-078154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]