Abstract

Topical steroids, commonly used for a wide range of skin disorders, are associated with side effects both systemic and cutaneous. This article aims at bringing awareness among practitioners, about the cutaneous side effects of easily available, over the counter, topical steroids. This makes it important for us as dermatologists to weigh the usefulness of topical steroids versus their side effects, and to make an informed decision regarding their use in each individual based on other factors such as age, site involved and type of skin disorder.

Keywords: Cutaneous, adverse, steroids

What was known?

Topical corticosteroids, though very useful for treatment of dermatological disorders can produce various side effects.

Some of these side effects may seriously damage the skin.

Hence, topical corticosteroids should be used with utmost caution.

Introduction

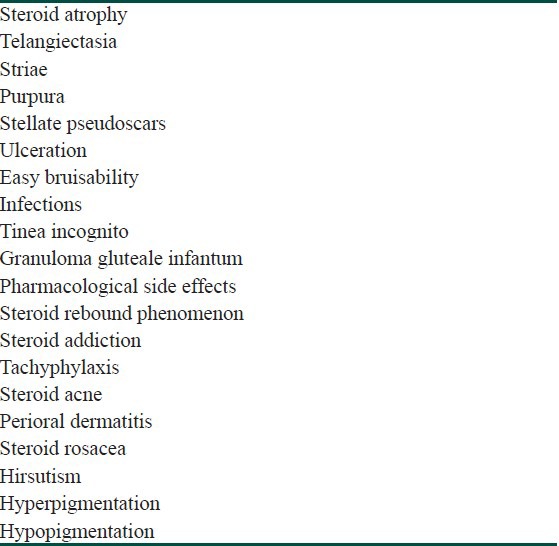

Topical steroids were introduced in 1951, when Sulzberger and Witten first used topical hydrocortisone.[1] The anti-inflammatory and anti-proliferative actions of topical steroids result not only in their therapeutic effect but also in their side effects [Table 1]. In this way steroids act as a double-edged sword, which makes it important to use it with the utmost caution.

Table 1.

Adverse effects of topical steroids on skin

Adverse Effects of Topical Steroids on Skin

Steroid Atrophy [Figure 1]

Figure 1.

Atrophy: Wrinkling and thinning of skin 4 weeks after irregular use of Mometasone

Physiology of skin atrophy due to topical steroids

Topical steroids cause the synthesis of lipocortin, which inhibits the enzyme phospholipase A2. Phospholipase A2 acts on the cell membrane phospholipids, to release arachidonic acid which causes the inflammation. The inhibition of phospholipase A2 results in the reduction of inflammation, mitotic activity and protein synthesis.[2]

Topical steroid use causes skin to go through three phases—preatrophy, atrophy and finally tachyphylaxis. Atrophy causes a burning sensation, and further steroid use causes vasoconstriction and soothing of the burning. When topical steroids are withdrawn, vasodilation occurs, till the vessels become more dilated than their initial diameter, and this is known as a “trampoline-like effect”. This occurs due to the effect of steroids on nitric oxide in the endothelium. Release of endothelial nitric oxide stores results in “hyperdilation” of vessels.[3]

Pathogenesis of skin atrophy due to topical steroids

Inhibitory effect on keratinocyte proliferation in the epidermis

Inhibition of collagen 1 and 3 synthesis in the dermis

Inhibition of fibroblasts and hyaluronan synthase 3 enzyme resulting in the reduction of hyaluronic acid in the extracellular matrix leading to dermal atrophy.[1,4]

Factors that increase chances of atrophy are: Extremities of age, body site e.g. intertriginous areas, high-potency topical steroid, occlusion and moisture.

Steroid-Induced Telangiectasia

Steroid-induced telangiectasia occurs due to stimulation of release of nitric oxide from dermal vessel endothelial cells leading to abnormal dilatation of capillaries.[1]

Steroid Acne

The pathogenesis of topical steroid-induced acne has been proposed to be due to the degradation of the follicular epithelium, resulting in the extrusion of the follicular content.[1]

Factors predisposing to steroid acne are high concentration of the drug, application under occlusion, young adults below age 30, whites in preference to blacks and application to acne-prone areas of face and upper back.

Steroid Rosacea

Topical steroids increase the proliferation of Propionibacterium acnes, and Demodex folliculorum, leading to an acne rosacea-like condition within 6 months. It is also known as “iatrosacea”, “topical steroid-induced rosacea-like dermatitis” (TCIRD) or “topical steroid-dependent face” (TSDF) [Figure 2].[5] Mometasone furoate, known to be safe for use on the face, in reality is a medium-potency steroid, and has resulted in “mometasone-induced steroid rosacea”.[6] Steroid-induced rosacea has been commonly associated with topical fluorinated steroids.[5]

Figure 2.

Topical steroid - dependent face. Used as fairness cream for 2 months

Perioral Dermatitis

Facial perioral dermatitis, more commonly seen in females, presents with follicular papules and pustules on an erythematous background, with sparing of the skin near the vermillion border of the lips. Steroid-induced perioral dermatitis is differentiated from common perioral dermatitis by history and clinical examination. Steroid-induced dermatitis has more erythema, inflammation, and scaling than its counterparts. Patients with steroid-induced dermatitis present with squeezed tubes of steroids that they have used and abused in hope of resolution of the skin condition. Hence, the term “tortured tube” sign. Substitution of hydrocortisone for fluorinated steroids resulted in the improvement of steroid-induced perioral dermatitis.[1,7,8]

Purpura, Stellate Pseudoscars, Ulcerations

Steroid-induced protein degradation leads to dermal atrophy and loss of intercellular substance, which further cause blood vessels to lose their surrounding dermal matrix, resulting in the fragility of dermal vessels, purpuric hypopigmented, and depressed scars.[1]

Aggravation of Cutaneous Infections

Tinea versicolor, onychomycosis, dermatophytosis and Tinea incognito [Figure 3] are the common cutaneous infections aggravated by topical steroids. Granuloma gluteale infantum is a persistent reddish purple, granulomatous, papulonodular eruption on the buttocks and thighs of infants. It occurs when diaper dermatitis is treated with topical steroids.[1]

Figure 3.

Tinea incognito and broad striae on axilla

Delayed Wound Healing

Delayed wound healing may occur due to various reasons. Inhibition of keratinocytes may cause epidermal atrophy and delayed re-epithelialization. Inhibition of fibroblasts-reduced collagen and ground substance may result in dermal atrophy and striae. Inhibition of vascular connective tissue may cause telangiectasia and purpura. Delayed granulation tissue formation may be caused by inhibition of angiogenesis.[1]

Contact Sensitization to Topical Steroids

Contact sensitization may occur due to prolonged use of steroids and application of certain drugs (e.g. nonfluorinated steroids - hydrocortisone, hydrocortisone 17-butyrate, budesonide). It is associated with cream formulations of steroids more often than ointments. Contact sensitization to topical steroids occurs due to the binding to amino acid arginine as part of certain proteins. Contact sensitization to steroids must be differentiated from hypersensitivity to other constituents e.g. lanolin, parabenes, antibiotics.[1]

Allergic contact dermatitis to topical steroids, presents as absence of response to treatment or as worsening of the dermatitis. It is usually seen in children with atopic dermatitis. Also, mild potent, steroids used commonly in children like desonide and hydrocortisone butyrate have an allergic property due to their structural instability. Some commonly used potent steroids are rare allergens, e.g. fluorinated corticosteroids, clobetasol propionate, betamethasone dipropionate, mometasone, etc.[9]

Eyelid Dermatitis

Patients with atopic and seborrheic dermatitis on chronic topical steroids, develop a flare around the eyes within 5-7 days after stoppage of steroids.

Tachyphylaxis

Topical corticosteroids may induce tachyphylaxis with chronic use. This is why the frequency of application of ultrahigh-potency topical corticosteroids is reduced after the first 2 weeks to no more than four or five times a week. Initially, steroids are effective; however, as time passes, patients stop responding to the same topical steroid and require oral steroids. Patients usually complain that steroids “are not effective anymore”.[1]

Trichostasis Spinulosa

A study has shown the association of trichostasis spinulosa with topical steroids. It is characterized by dark-brown, follicular papules involving the face, neck, upper chest, arms, and antecubital areas with a rough sensation on palpation. On examination, tufts of hairs are visible projecting through each of the tiny papules. Treatment involves daily tretinoin 0.05% cream.[10]

Striae (Rubrae Distensae)

Striae due to steroids must be differentiated from those due to weight gain and pregnancy.

Pathogenesis of striae, according to Shuster, is due to the cross linking of immature collagen in the dermis, resulting in intradermal tears causing striae [Figure 4].[11] Studies also show that deposition of collagen and scar tissue formation are implicated in the formation of striae.[1]

Figure 4.

Striae due to topical steroid applied for 3 weeks for atopic dermatitis

Post Peel (Laser) Erythema Syndrome

Persistent redness of the face, after peel or laser has been noted in patients using topical steroids before the procedure.[3]

Status Cosmeticus

Women with status cosmeticus cannot tolerate makeup and complain of a continuous burning sensation after any application. Patients present with erythema and burning disproportionate to the redness. Examination reveals atrophy, telangiectasia, and acneiform papules. With steroid withdrawal, the atrophy eventually clears.[3]

Chronic Actinic Dermatitis-Like Eruption

Patients present with facial erythema and lichenification on the face, forearms and upper neck. The difference between this condition and photo exacerbated dermatitis is that even though the rash is on the photo distributed area, it does not flare on sun exposure.[3]

Corticosteroid Withdrawal Patterns

The pattern of corticosteroid withdrawal is as follows: A week after corticosteroids are stopped, a mild erythema occurs at the site of the original dermatitis. This flare lasts for 2 weeks ending with desquamation. Dermatitis localized to the eyelids, face, scrotum, or perianal area often persists. A second flare usually occurs within 2 weeks. This pattern of flare and resolution repeats itself but each time smaller duration of flares and longer resolution periods. The length of the time for which steroids had been used initially determines the duration of the withdrawal phase.[3]

Conclusion

The key to safe use of topical steroid is short term use of appropriate potency steroid. However, when the skin condition remains resistant to treatment or affects a particular sensitive area, the prolonged use of steroids is not advisable. Selective glucocorticoid receptor agonists are being developed that have independent transrepression and transactivation action. This may lead to the development of a topical steroid without its adverse effects.[12]

What is new?

The key to safe use of topical steroid is short term use of appropriate potency steroid.

Prolonged use of steroids is not advisable.

Selective glucocorticoid receptor agonists are being developed that have independent transrepression and transactivation action.

This may lead to the development of a topical steroid without its adverse effects.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Hengge UR, Ruzicka T, Schwartz RA, Cork MJ. Adverse effects of topical glucocorticosteroids. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brazzini B, Pimpinelli N. New and established topical corticosteroids in dermatology: Clinical pharmacology and therapeutic use. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2002;3:47–58. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200203010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rapaport MJ, Lebwohl M. Corticosteroid addiction and withdrawal in the atopic: The red burning skin syndrome. Clin Dermatol. 2003;21:201–14. doi: 10.1016/s0738-081x(02)00365-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schoepe S, Schäcke H, May E, Asadullah K. Glucocorticoid therapy-induced skin atrophy. Exp Dermatol. 2006;15:406–20. doi: 10.1111/j.0906-6705.2006.00435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhat YJ, Manzoor S, Qayoom S. Steroid-induced rosacea: A clinical study of 200 patients. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:30–2. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.77547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fisher DA. Adverse effects of topical corticosteroid use. West J Med. 1995;162:123–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sneddon I. Perioral dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 1972;87:430–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1972.tb01590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fowler KP, Elpern DJ. “Tortured tube” sign. West J Med. 2001;174:383–4. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.174.6.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saraswat A. Topical corticosteroid use in children: Adverse effects and how to minimize them. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:225–8. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.62959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janjua SA, McKoy KC, Iftikhar N. Trichostasis spinulosa: Possible association with prolonged topical application of clobetasol propionate 0.05% cream. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:982–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.03271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shuster S. The cause of striae distensae. Acta Derm Venerol Suppl (Stockh) 1979;59:161–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khan MO, Lee HJ. Synthesis and pharmacology of anti-inflammatory steroidal antedrugs. Chem Rev. 2008;108:5131–45. doi: 10.1021/cr068203e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]