Abstract

A 55-year-old woman presented with a 5-year history of livedo racemosa on her limbs. Histology showed vasculitis of medium-sized arteries with a circumferential, hyalinised, intraluminal fibrin ring. Her laboratory investigations did not indicate any underlying systemic disease. The findings were consistent with lymphocytic thrombophilic arteritis (LTA), alias macular arteritis, which is a recently described entity. The importance of LTA lies in the fact that it is a close clinical and microscopic mimic of polyarteritis nodosa (PAN). LTA is believed to be a distinct entity by some and as a form of PAN by others. We have discussed this case in our report.

Keywords: Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa, livedo racemosa, lymphocytic thrombophilic arteritis, macular arteritis

What was known?

Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa (CPAN) is an indolent medium vessel vasculitis that spares the viscera. The recently described macular arteritis or lymphocytic thrombophilis arteritis overlaps clinically and microscopically with CPAN. There have been no cases reported from India so far.

Introduction

Lymphocytic thrombophilic arteritis (LTA) is a newly described medium vessel arteritis of the skin.[1] LTA commonly presents as hyperpigmented macules and runs an indolent clinical course. It overlaps considerably with polyarteritis nodosa (PAN), but lacks systemic features. To the best of our knowledge, this has not been reported from India so far.

Case Report

A 53-year-old south Indian lady presented with a 5-year history of reddish patches over both lower limbs and arms. Since past 10 days, they were mildly itchy and painful. The lesions first started on the lower limb as small red patches, which slowly increased in size and healed with residual hyperpigmentation. The lesions were present on and off and had no aggravating or relieving factors. The patient had no history of drug intake. She applied topical creams for the past 3-4 months, without any benefit. The patient did not have diabetes mellitus, hypertension, or symptoms of systemic involvement. She did not smoke. Her obstetric history was uneventful.

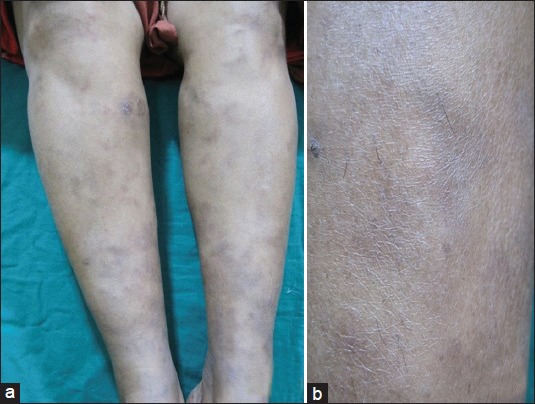

On examination, there were multiple erythematous patches and hyperpigmented macules associated with livedo racemosa on both legs and arms [Figure 1a and b]. On palpation, focal areas of mild induration were noted, but no nodules were palpable. There was no evidence of limb ischemia or ulceration/scarring/purpura. Her nails appeared unremarkable. Her blood pressure recording was normal and digital pulses were felt. The rest of her systemic examination was unremarkable. A clinical diagnosis of panniculitis was considered. Her laboratory investigations, which included testing for anti-nuclear antibodies, anti-dsDNA, ANCA, and anti-phospholipid antibodies were negative. Total leucocyte count, platelet count, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate were normal. Mantoux test was strongly positive.

Figure 1.

(a) Livedo racemosa over the lower limbs. (b) Mottled hyperpigmentation involving both legs a

Histopathology

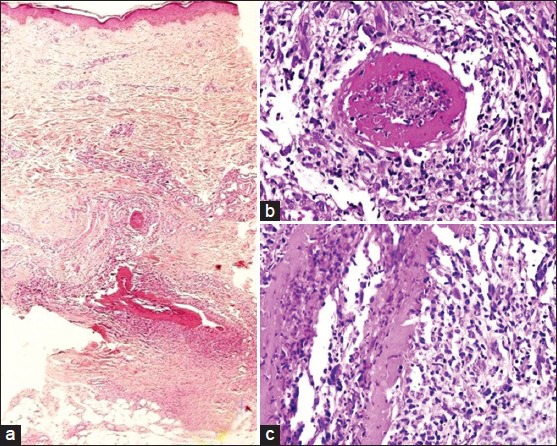

A 3-mm punch biopsy of the skin with subcutis was taken. The epidermis and dermis were unremarkable. The medium-sized arteries in the deep dermis showed thickening of their walls with a hyalinised fibrin ring involving the entire circumference of the vessel [Figure 2a and b]. Nuclear dust was noted in the vessel walls and within the lumina [Figure 2c]. A predominant lymphohistiocytic infiltrate admixed with a few eosinophils were observed surrounding these vessels. There were no intact neutrophils in the infiltrate. There were no granulomas or panniculitis. Elastic van Gieson stain showed an intact internal elastic lamina.

Figure 2.

(a) Involvement of medium sized arteries in deep dermis (H and E, ×100). (b and c) Concentric hyalinised fibrin ring involving the vessel wall. Note the perivascular and intraluminal lymphocytic infiltrate and nuclear dust (H and E, ×200)

Management and Follow-up

The patient was treated with Dapsone, 100 mg/day for 3 months, and Doxycycline, 100 mg/day for 1 month. About 80% of the lesions cleared in 4 months. No fresh lesions have surfaced at 6-months follow-up.

Discussion

Cutaneous vasculitis encompass a spectrum of disorders with varied aetiology. They are classified mainly based on the size of the involved vessels.[2] The conditions under medium-sized arteritis are PAN and Kawasaki disease. Cutaneous PAN (CPAN) is characterised by necrotising arteritis presenting as tender nodules or livedo reticularis. Systemic manifestions like myalgia, neuropathy, hypertension, and weight loss are noted occasionally, but viscera are spared.[3]

In 2003, the term “macular arteritis” was first used to describe a form of medium vessel vasculitis in African American patients presenting as hyperpigmented macules, without the classic features such as palpable purpura or erythematous and tender nodules.[4] Subsequently, there was a report of two Japanese patients with similar features.[5] All these patients had longstanding (4 months to 15 years) hyperpigmented lesions, some of them with a reticular pattern and no palpable nodules. Histologically, they were all characterised by fibrinoid necrosis of medium-sized arteries with lymphocytic infiltrates, leading to endarteritis obliterans. All these patients had an indolent clinical course, with no demonstrable improvement despite treatment.

In 2008, Lee and Kossard used the term LTA to describe a similar vasculitis in 5 young women with a characteristic intraluminal hyalinised fibrin ring and lymphocytic infiltrates with a scarcity of neutrophils.[1] Clinically, these patients had progressive pigmentation, livedo racemosa, and palpable mild induration. Four patients had associated anti-phospholipid antibodies on serology. They felt that LTA is a better suited term than macular arteritis, since the lesions are not just macular and also to underline the associated thrombophilic status.

LTA appears to be more common in young women of non-Caucasian origin.[1] Occasional cases have been seen in men and children.[6,7] Our patient presented at an age older than those described so far. The lesions are asymptomatic and have a predilection for lower extremities, which is usually the first to be involved, and they slowly progress to involve the upper limbs, although to a lesser extent.[1,8]

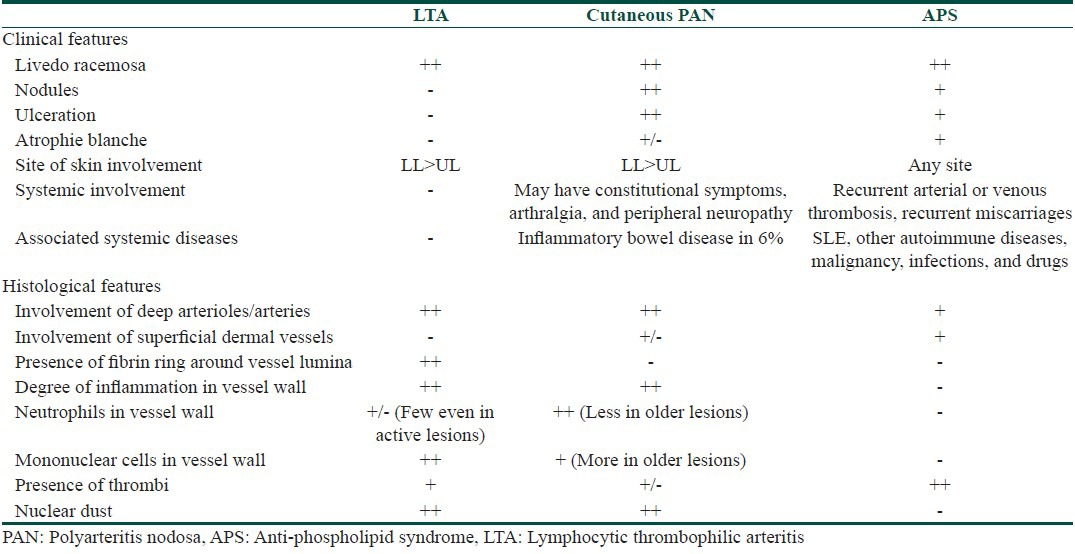

The most important differential diagnoses to be considered are anti-phospholipid syndrome (APS) and cutaneous PAN (CPAN).[1] The characteristic clinicopathological features of LTA, CPAN, and APS are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Some patients of LTA show increased levels of anti-phospholipid antibodies, but did not satisfy the clinical or laboratory criteria; the significance of this finding is unknown. CPAN or “limited” PAN was first described by Lindberg in 1931.[9] It characteristically presents as painful subcutaneous nodules, associated with mild constitutional symptoms. While many authors believe that CPAN is a distinct entity, several others view it just as an evolutionary stage in classic PAN.[10]

The histology of CPAN encompasses four stages.[11] The first, or acute stage, shows neutrophilic infiltration of vessels at the dermis–subcutis junction, with fibrin thrombi. There is no fibrinoid necrosis or disruption of the internal elastic lamina (IEL). The second stage shows fibrinoid necrosis with disruption of the media and IEL. The infiltrate is now joined by lymphocytes and histocytes. This stage shares a lot of microscopic similarities with LTA and has led to the idea that LTA is just a form of CPAN.

While there is certainly a histologic overlap, there are also a lot of differences from CPAN. The IEL is stated to be intact in macular arteritis, in contrast to CPAN at a similar stage. However, Lee et al., have not commented on this aspect in their original series of 5 patients.[1] Gupta et al., have recorded an intact IEL in their case.[8] Our case showed a preserved IEL. In the third and fourth (healing) stages, CPAN shows obliteration of the lumen, fibroblastic reaction, and proliferation of small vessels in the perivascular area. Despite lesions being present for 5 years in our patient, there were no signs of healing and the biopsy, with its fibrin ring, seems to represent an active lesion. In order to see the characteristic microscopic features of CPAN, one needs to biopsy the nodular/active areas and, often, multiple step sections are necessary. In contrast, the biopsy site was randomly chosen in our patient and the changes were easily identified in the initial section. Neutrophils are absent in LTA or very few if present.

Another important microscopic mimic is superficial thrombophlebitis.[12] Veins can have a partial IEL and are likely to be mistaken for arteries. The presence of concentric layers of elastic fibres among the smooth muscle bundles characterizes a vein and elastic stains should be employed in all cases with vascular pathology of the medium calibre vessels.

A curious association in our case is the strongly positive Mantoux test. Papulonecrotic tuberculid (PNT) is known to be associated with Takayasu arteritis.[13] Phlebitic granulomatous tuberculid has also been described.[14] In the present biopsy, we did not find any granulomatous inflammation and the clinical presentation was incompatible with that of tuberculosis; this might be just a chance concurrence.

Stabilization of the lesions of LTA is noted in some patients without any treatment. Others have been treated with low dose steroids and warfarin, without much benefit.[1,8] In all the cases described so far, the course appears indolent without any systemic signs.

Conclusion

LTA (or “macular arteritis”) is an idiopathic, indolent form of cutaneous medium vessel arteritis without a systemic component and a characteristic hyaline fibrin ring encircling the lumen. While there are microscopic differences from CPAN, the small numbers of cases reported so far do not amount to conclusive testimony. It is important to recognize these features to accumulate evidence to support its candidature as a distinct vasculitis or consider it as a morphologic “pattern” in the spectrum of PAN.

What is new?

Despite the striking histopathological features, it may be difficult to distinguish LTA from CPAN. The bottom-line is that patients with such a “hyalinised fibrinring” need to be screened for occult, potentially serious systemic causes of vasculitis.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Lee JS, Kossard S, McGrath MA. Lymphocytic thrombophilic arteritis: A newly described medium-sized vessel arteritis of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1175–82. doi: 10.1001/archderm.144.9.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Andrassy K, Bacon PA, Churg J, Gross WL, et al. Nomenclature of systemic vasculitides. Proposal of an international consensus conference. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37:187–92. doi: 10.1002/art.1780370206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lightfoot RW, Jr, Michel BA, Bloch DA, Hunder GG, Zvaifler NJ, McShane DJ, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of polyarteritis nodosa. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:1088–93. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fein H, Sheth AP, Mutasim DF. Cutaneous arteritis presenting with hyperpigmented macules: Macular arteritis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:519–22. doi: 10.1067/s0190-9622(03)00747-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sadahira C, Yoshida T, Matsuoka Y, Takai I, Noda M, Kubota Y. Macular arteritis in Japanese patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:364–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Daraji W, Gregory AN, Carlson JA. “Macular arteritis”: A latent form of cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa? Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:145–9. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e31816407c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buckthal-McCuin J, Mutasim DF. Macular arteritis mimicking pigmented purpuric dermatosis in a 6-year-old Caucasian girl. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:93–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2008.00831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta S, Mar A, Dowling JP, Cowen P. Lymphocytic thrombophilic arteritis presenting as localized livedo racemosa. Australas J Dermatol. 2011;52:52–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2010.00673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindberg K. Ein beitnag zur kenntsnis der periarteritis nodosa. Acta Med Scand. 1931;76:183–25. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khoo BP, Ng SK. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa: A case report and literature review. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1998;27:868–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishibashi M, Chen KR. A morphological study of evolution of cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:319–26. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181766190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen KR. The misdiagnosis of superficial thrombophlebitis as cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa: Features of the internal elastic lamina and the compact concentric muscular layer as diagnostic pitfalls. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:688–93. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181d7759d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rose AG, Sinclair-Smith CC. Takayasu's arteritis. A study of 16 autopsy cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1980;104:231–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parker SC. Phlebitic tuberculid: A new tuberculid? J Cutan Pathol. 1989;16:319. [Google Scholar]