Abstract

Background

The opportunity to improve care by delivering decision support to clinicians at the point of care represents one of the main incentives for implementing sophisticated clinical information systems. Previous reviews of computer reminder and decision support systems have reported mixed effects, possibly because they did not distinguish point of care computer reminders from e‐mail alerts, computer‐generated paper reminders, and other modes of delivering ‘computer reminders’.

Objectives

To evaluate the effects on processes and outcomes of care attributable to on‐screen computer reminders delivered to clinicians at the point of care.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane EPOC Group Trials register, MEDLINE, EMBASE and CINAHL and CENTRAL to July 2008, and scanned bibliographies from key articles.

Selection criteria

Studies of a reminder delivered via a computer system routinely used by clinicians, with a randomised or quasi‐randomised design and reporting at least one outcome involving a clinical endpoint or adherence to a recommended process of care.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently screened studies for eligibility and abstracted data. For each study, we calculated the median improvement in adherence to target processes of care and also identified the outcome with the largest such improvement. We then calculated the median absolute improvement in process adherence across all studies using both the median outcome from each study and the best outcome.

Main results

Twenty‐eight studies (reporting a total of thirty‐two comparisons) were included. Computer reminders achieved a median improvement in process adherence of 4.2% (interquartile range (IQR): 0.8% to 18.8%) across all reported process outcomes, 3.3% (IQR: 0.5% to 10.6%) for medication ordering, 3.8% (IQR: 0.5% to 6.6%) for vaccinations, and 3.8% (IQR: 0.4% to 16.3%) for test ordering. In a sensitivity analysis using the best outcome from each study, the median improvement was 5.6% (IQR: 2.0% to 19.2%) across all process measures and 6.2% (IQR: 3.0% to 28.0%) across measures of medication ordering.

In the eight comparisons that reported dichotomous clinical endpoints, intervention patients experienced a median absolute improvement of 2.5% (IQR: 1.3% to 4.2%). Blood pressure was the most commonly reported clinical endpoint, with intervention patients experiencing a median reduction in their systolic blood pressure of 1.0 mmHg (IQR: 2.3 mmHg reduction to 2.0 mmHg increase).

Authors' conclusions

Point of care computer reminders generally achieve small to modest improvements in provider behaviour. A minority of interventions showed larger effects, but no specific reminder or contextual features were significantly associated with effect magnitude. Further research must identify design features and contextual factors consistently associated with larger improvements in provider behaviour if computer reminders are to succeed on more than a trial and error basis.

Plain language summary

On screen point of care computer reminders to improve care and health

It is known that doctors do not always provide the care that is recommended or according to the latest research. Many strategies have been tried in an attempt to reduce this gap between what is recommended and what is done. A potentially low cost way to do this could be to use computer systems that remind physicians about important information while they make decisions. For example, a doctor could be ordering antibiotics for a child with an ear infection. At that point, the computer the doctor is working on displays a pop up window with a reminder about the evidence for the best dose and length of time the antibiotics should be prescribed.

This review found 28 studies that evaluated the effects of different on‐screen computer reminders. The studies tested reminders to prescribe specific medications, to warn about drug interactions, to provide vaccinations, or to order tests. The review found small to moderate benefits. The reminders improved physician practices by a median of 4%. In eight of the studies, patients' health improved by a median of 3%.

Although some studies showed larger benefits than these median effects, no specific reminders or features of how they worked were consistently associated with these larger benefits. More research is needed to identify what types of reminders work and when.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Summary of findings.

| Point‐of‐care computerized decision support systems with or without co‐intervention(s) compared with usual care or co‐intervention(s) | ||||||||

|

Patient or population: Physicians (any specialty) Settings: Point‐of‐care; the interventions were most commonly delivered in the outpatient setting, but were also delivered in the inpatient, long‐term care, and other clinical settings. The majority of interventions occurred in the United States, but interventions also occurred in several other countries Intervention: On‐screen tools designed to aid clinical decision‐making, with or without co‐intervention(s), that were delivered within routinely‐used clinical information systems (e.g. an electronic health record), accessible via physicians' usual workflow, and targeted the physician responsible for the clinical decision for which the on‐screen tool was providing support Comparison: Usual care or co‐intervention(s) | ||||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect: RR (95% CI) | Absolute effect: Median of median absolute improvements (IQR) | Absolute effect: Best of median absolute improvements (IQR) | No of Participants (Comparisons) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed likelihood of outcome with comparison | Corresponding likelihood of outcome with intervention | |||||||

| All process outcomes | 1.29 (1.23 to 1.36) |

2.71% (0.52% to 9.5%) | 935 192 (114) |

Low1 | ||||

| Prescription of medications | 405 per 1000 | 470 per 1000 (454 to 486) |

1.16 (1.12 to 1.20) |

2.41% (‐0.08% to 6.76%) | 276 410 (64) |

Low2 | ||

| Prescription of recommended vaccines | 255 per 1000 | 386 per 1000 (329 to 451) |

1.51 (1.29 to 1.77) |

4.8% (1.56% to 7.65%) | 212 791 (30) |

Moderate3 | ||

| Test ordering | 412 per 1000 | 494 per 1000 (461 to 531) |

1.20 (1.12 to 1.29) |

1.96% (0.68% to 8.4%) |

539 528 (25) |

Low4 | ||

| Elements of recommended documentation | 275 per 1000 | 481 per 1000 (407 to 569) |

1.75 (1.48 to 2.07) |

6.08% (1.14% to 20.5%) |

66 725 (11) |

Low5 | ||

| Other process outcomes | 165 per 1000 | 269 per 1000 (243 to 299) |

1.63 (1.47 to 1.81) |

4.32% (1.03% to 10.4%) |

300 114 (32) |

Low1 | ||

|

RR: Risk Ratio; CI: Confidence interval; IQR: interquartile range *The basis for the assumedlikelihood of outcome with comparison was the median proportion of outcome recipients in the control group across studies, determined following application of the intervention to the intervention group.. The corresponding likelihood of outcome with intervention (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the RR of the intervention (and its 95% CI). | ||||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||||

1Quality of the evidence was downgraded by two levels. The evidence was downgraded by one level due to inconsistency; a notable minority of studies had anomalously large positive effect sizes, and quantitative measures of heterogeneity (I2 value and χ2 test) indicated the presence of inconsistency. The evidence was further downgraded by one level due to publication bias, as the funnel plot had substantial asymmetry in the direction of unduly favouring the intervention.

2Quality of the evidence was downgraded by two levels. Risk of bias downgraded the evidence by one level, as a substantial proportion of studies had a high risk of dissimilar baseline characteristics (24/64) and smaller but non‐negligible proportions of studies had high risks of other biases. Inconsistency also downgraded the evidence by one level, due to some studies reporting anomalously large positive effect sizes and quantitative measures of heterogeneity (I2 value and χ2 test) indicating the presence of inconsistency.

3Quality of the evidence was downgraded by one level due to inconsistency, which was indicated by quantitative measures of heterogeneity (I2 value and χ2 test).

4Quality of the evidence was downgraded by two levels. The evidence was downgraded by one level due to inconsistency, which was indicated by quantitative measures of heterogeneity (I2 value and χ2 test). The evidence was further downgraded by one level due publication bias. The funnel plot displayed substantial asymmetry in the direction of unduly favouring the intervention.

5Quality of the evidence was downgraded by two levels. The evidence was downgraded by one level due to inconsistency. Inconsistency was indicated by variation in study effect sizes, with multiple studies reporting anomalously large positive effect sizes and one study reporting an abnormally large negative effect size. There was also a borderline lack of confidence interval overlap between studies, and the presence of inconsistency was corroborated by quantitative measures of heterogeneity (I2 value and χ2 test). The evidence was downgraded by one additional level due to publication bias, as the funnel plot displayed substantial asymmetry in the direction of unduly favouring the intervention.

Background

Description of the condition

Gaps between recommended practice and routine care are widely known (McGlynn 2003; Quality of Health Care 2001; Schuster 1998). Interventions designed to close these gaps fall into a number of different categories: educational interventions (directed at clinicians or at patients), reminders (again, directed at clinicians or patients), audit and feedback of performance data, case management, and financial incentives to name a few (Shojania 2005). However, none of these categories of interventions confers large improvements in care, especially when evaluated rigorously. In fact, they often produce quite small benefits (Grimshaw 2004; Oxman 1995; Shojania 2006; Walsh 2006) and these benefits tend to involve process measures only, not patient outcomes.

Description of the intervention

Given the difficulty of changing the behaviour of healthcare providers and the resources required by many of the interventions that aim to do so, provider reminders offer a promising strategy, especially given their low marginal cost. Reminders delivered at the point of care prompt healthcare professionals to recall information that they may already know but could easily forget in the midst of performing other activities of care, or, in the case of decision support, provide information or guidance in an accessible format at a particularly relevant time. Paper‐based reminders have existed for many years and have ranged from simple notes attached to the fronts of charts (for example reminding providers of the need to administer an influenza vaccine) to more sophisticated pre‐printed order forms that include decision support (for example protocols for ordering and monitoring anti‐coagulants). Computer‐based reminders have the potential to address multiple topics and are automatic; therefore they represent a subset of reminders of great interest to those involved in quality improvement efforts.

How the intervention might work

A number of systematic reviews over the years have evaluated computerised reminders and decision support systems (Dexheimer 2008; Garg 2005; Hunt 1998; Kawamoto 2005). However, these reviews have tended to lump all forms of computerised reminders and decision support together, including, for instance, computer‐generated paper reminders and e‐mail alerts sent to providers, along with reminders generated at the point of care. It is this last category, computer reminders that prompt providers at the point of care, which represents the most promising form of computerised reminders. Such reminders, embedded into computerised provider order entry systems or electronic medical records, alert providers to important clinical information relevant to a targeted clinical task at the time the provider is engaged in performing the task.

Why it is important to do this review

While point of care computerised reminders have produced some well‐known successes (Dexter 2001; Kucher 2005; Overhage 1997), other trials have shown no improvements in care (Ansari 2003; Eccles 2002a; Montgomery 2000), including studies from institutions with well‐established computerised order entry systems (Dexter 2004; Sequist 2005; Tierney 2003). Therefore, we sought to quantify the expected magnitudes of improvements in processes and outcomes of care through the use of computerised reminders and decision support delivered at the point of care, and identify any features consistently associated with larger effects.

Objectives

In this review, we address the following questions:

Do on‐screen computer reminders effectively improve processes or outcomes of care?

Do any readily identifiable elements of on‐screen reminders influence their effectiveness (e.g. inclusion of patient‐specific information as opposed to generic reminders for a given condition, requiring a response from users).

Do any readily identifiable elements of the targeted activity (e.g. chart documentation, test ordering, medication prescribing) influence the effectiveness of on‐screen reminders?

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (with randomisation at the level of the patient or the provider) and quasi‐randomised trials, where allocation to intervention or control occurred on the basis of an arbitrary but not truly random process (for example even or odd patient identification numbers).

Types of participants

Any study in which the majority of participants (> 50%) consisted of physicians or physician trainees; we excluded studies that primarily targeted dentists, pharmacists, nurses, or other health professionals.

Types of interventions

The original protocol for this review defined 'on‐screen computer reminders' as follows:

Patient or encounter specific information that is provided via a computer console (either visually or audibly) and intended to prompt a healthcare professional to recall information usually encountered through their general medical education, in the medical records or through interaction with peers, and so remind them to perform or avoid some action to aid individual patient care (Gordon 1998).

This original definition served primarily to distinguish computer reminders that were literally presented to users on a computer screen (hence 'on‐screen reminders') from computer‐generated reminders that were simply printed out and placed in a paper chart. While this distinction remains germane (i.e. some studies still involve 'computer reminders' that are really paper‐based reminders that happen to have been generated by a computer), the use of computers in healthcare is now sufficiently widespread that the more important concept has become 'at the point of care', rather than merely 'on‐screen'. A reminder that is ‘on screen’ but not noticeable to clinicians during the target activities of interest is no more useful than a paper reminder placed in such a manner that clinicians must deviate from their usual charting activities in order to find it.

Thus, from an operational point of view, the focus of this review should be regarded as evaluating 'point‐of‐care computer reminders'. By 'point of care' we refer to delivery of the computer reminder to clinicians at the time they are engaged in the target activity of interest, such as prescribing medications, documenting clinical encounters in the medical record, and ordering investigations.

Operationally, we considered a reminder to qualify as delivered at the point of care if the following three criteria applied.

The reminder was delivered via the computer system routinely used by the providers targeted by the intervention ‐ typically an electronic medical record or computerised order entry program. For instance, a dedicated computer used solely for performing dose calculations for anticoagulants would not count as 'on‐screen/point of care', since it requires clinicians to depart from their usual workflow in order to avail themselves of the reminder or decision support provided by this separate system. We excluded such systems because they in effect require providers to remember to use the reminder system, thus undermining the fundamental purpose of a reminder.

The reminder was accessible from within the routinely used clinical information system (typically via a pop‐up screen or an icon that indicates the availability of the reminder or decision support feature). A decision support module that could only be accessed by remembering to call up a separate program or website would not count as a point of care reminder (again, because depending on clinicians’ remembering to call up the program without any prompting violates the notion of a ‘reminder’).

The reminder targeted the person responsible for the relevant clinical activity. For instance, if handwritten physician orders were entered by a clerk or pharmacist into a computer order entry system, any alert or decision support delivered via the computer system would not qualify as 'point of care' since, for the physician, it was the handwritten order that occurred at the point of care.

For settings without general computer order entry or electronic medical record systems, we allowed the possibility that some specific activities might still routinely occur using a computer system. For instance, an ambulatory clinic might have developed a computer‐based system for supporting preventive care activities, even if the rest of the ambulatory record remained paper‐based. Or, a hospital might have developed a computer program for ordering certain high‐risk drugs (for example chemotherapy or anticoagulants). If a study documented that over 90% of the target activity occurred using the computer system, we regarded such a system as delivering a de‐facto point of care computer reminder (since the documentation of > 90% use of the computer system for that activity implies that providers would generally not have to remember to use to the reminder).

Types of outcome measures

Eligible outcomes

In order to enhance the interpretability of the results, we categorised eligible outcomes as follows.

Dichotomous process adherence outcomes: the percentage of patients receiving a target process of care (e.g. prescription of a specific medication, documentation of performance of a specific task, such as referral to a consultant) or whose care was in compliance with an overall guideline.

Dichotomous clinical outcomes: true clinical endpoints (such as death or development of a pulmonary embolism), as well as surrogate or intermediate endpoints, such as achievement of a target blood pressure or serum cholesterol level.

Continuous clinical outcomes: various markers of disease or health status (e.g. mean blood pressure or cholesterol level).

Continuous process outcomes: any continuous measure of how providers delivered care (e.g. duration of antibiotic therapy, time to respond to a critical lab value).

We planned to include studies in the analysis only if they reported at least one clinical or process outcome (i.e. we excluded articles that reported only costs, lengths of stay, and other measures of resource use). As it turned out, meaningful analyses were possible only with the measures of process adherence. For these measures, in order to permit pooling across studies, we required that studies present data as the absolute percentage of patients who received the target process care in each study group (or in a manner that allowed us to calculate these percentages). For instance, we would not include a study that only reported the odds of patients receiving the process of care in the intervention group compared with the control. We made this decision partly because initial review revealed that the vast majority of studies reported their data as percentages of patients who received the process of interest, and partly because this format is most conducive to conveying the expected impacts of computer reminders, namely absolute improvements in adherence to a target process of care or clinical behaviour.

Primary outcomes

Although we planned to include any otherwise eligible study that reported the effect of computerised reminders on clinical outcomes, evaluating the impact of reminders on adherence to target processes of care represented the primary goal of our analysis. We recognise that improving patient outcomes represents the ultimate goal of any quality improvement activity. However, we focused on process improvements for this review because we wanted to capture the degree to which computer reminders achieve their main goal, namely changing provider behaviour (Mason 1999). The degree to which such behaviour changes ultimately improve patient outcomes will vary depending on the strength of the relationship between the targeted process of interest and patient level outcomes. In some cases, no such relationship may exist. For instance, the incentive to improve appropriate antibiotic use is usually the population level goal of reducing emergence of resistant microorganisms, not improving the outcomes of care for individual patients. In other cases, a presumed relationship between a given process of care and patient outcomes may be incorrect (for example we would no longer expect a reminder that encourages the use of hormone replacement therapy to improve cardiovascular outcomes in post‐menopausal women). Consequently, if we had focused on improvements in clinical endpoints and found that reminders achieved negligible improvements in such outcomes, we would not know if this reflected consistent failure of computer reminders to achieve their intended goal (changes in provider behaviour) or the fact that reminders had targeted processes with limited connections to patient outcomes.

Direction of improvements

Some studies target quality problems that involve ‘underuse,’ so that improvements in quality correspond to increases in the percentage of patients who receive a target process of care (for example increasing the percentage of patients who receive the influenza vaccine). However, other studies target ‘overuse’, so that improvements correspond to reductions in the percentage of patients receiving inappropriate or unnecessary processes of care (for example reducing the percentage of patients who receive antibiotics for viral upper respiratory tract infections). In order to standardise the direction of effects, all process outcomes were defined so that higher values represented an improvement. For example, data from a study aimed at reducing the percentage of patients receiving inappropriate medications would be captured as the complementary percentage of patients who did not receive inappropriate medications. Increasing this percentage of patients for whom providers did not prescribe the medications would thus represent an improvement.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the MEDLINE database up to July 2008 using Medical Subject Headings for relevant forms of clinical information systems (for example Medical Order Entry Systems, Point‐of‐Care Systems, Ambulatory Care Information Systems) and combinations of text words such as ‘computer’ or ‘electronic’ with terms such as ‘reminder’, ‘prompt’, ‘alert’, ‘cue’, and ‘support’ (Appendix 1 to Appendix 2). We applied a methodological filter for any type of clinical trial. We also searched the EMBASE, CINAHL and CENTRAL databases using modified search strategies up to July 2008. In addition,we retrieved all articles related to computers and reminder systems or decision support from the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group (EPOC) database (EPOC 2008) Finally, we scanned bibliographies from key articles. For non‐English language articles, we screened English translations of titles and abstracts and pursued full‐text translation where possible ( i.e. either to include or confirm exclusion).

Data collection and analysis

Study selection and data abstraction

Two investigators (from KS, AJ, AM) independently screened citations and abstracted included articles using a structured data entry form. In the initial screening, authors based their judgments about inclusion and exclusion solely on the titles and abstracts, but promoted articles to the next stage of the screening process whenever a decision could not be made with confidence. For the second stage of screening, we obtained full text for all references, with each article again judged independently by two authors.

Two authors independently abstracted the following information from articles that met all the inclusion criteria after the second stage of screening: clinical setting, participants, methodological details, characteristics of the reminders design and content, the presence of co‐interventions (for example educational materials or performance report cards distributed to clinicians in both study groups), and outcomes. The data abstraction form (available upon request) was based on the checklist developed by the Cochrane EPOC Group (EPOC 2008). The form was pilot tested and revised iteratively prior to its use for final data abstraction. We resolved discrepancies between authors during either the screening or abstraction stages by discussion between the two authors to achieve consensus. When a conflict could not be resolved, a third author was consulted to achieve consensus or generate a majority decision.

Quality assessment

As part of the data abstraction process, authors assessed the following quality criteria based on the Cochrane EPOC Group Data Collection Checklist: concealment of allocation, blinded assessment of primary outcomes, proportion of patients/providers followed up, baseline disparities in process adherence or outcomes in the study groups, protection against contamination, and unit of analysis errors (EPOC 2008).

Data analysis

We anticipated that the eligible studies would exhibit significant heterogeneity, due to variations in target clinical behaviours, patient and provider populations, methodological features, characteristics of the interventions, and the contexts in which they were delivered. One approach for addressing these sources of variation would involve meta‐regression. Given the number of potentially relevant covariates, however, meta‐regression would require many more studies than we anticipated finding. We also expected that many eligible studies would assign intervention status to the provider, rather than the patient, but would not take into account ‘cluster effects’ in the analysis (i.e. they would exhibit ‘unit of analysis errors’). Performing either a conventional meta‐analysis or meta‐regression using studies with unit of analysis errors would require us to make a number of assumptions about the magnitude of unreported parameters, such as the intra‐class correlation coefficients and the distributions of patients across clusters, in order to avoid spurious precision in 95% confidence intervals.

To preserve the goal of providing a quantitative assessment of the effects associated with computerised reminders, without resorting to numerous assumptions or conveying a misleading degree of confidence in the results, we chose to report the median improvement in process adherence (and inter‐quartile range) among studies that shared specific features of interest. This approach was first developed in a large review of strategies to foster the implementation of clinical practice guidelines (Grimshaw 2004) and subsequently applied to reviews of quality improvement strategies in a series of reports for the US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Shojania 2004a; Shojania 2004b; Steinman 2006; Walsh 2006).

This method of reporting the median effect sizes across groups of studies involves two distinct uses of the term ‘median’. First, in order to handle multiple outcomes within individual studies, we calculated for each study the median improvement in process adherence across the various outcomes reported by that study. For example, if a study reported 10 process adherence outcomes, we would calculate the absolute difference between intervention and control values for each outcome in order to obtain the median improvement (and interquartile range) across all 10 such differences. This median would then contribute the single effect size for that study. We also captured whenever a study identified a primary outcome and separately analysed those studies. Further, we performed a sensitivity analysis in which, instead of the median outcome, we used the best outcome from each study. With each study then represented by a single, median outcome, we then calculated the median effect size and interquartile range across all included studies. It is this second use of the ‘median’ that is crucial to the method. Instead of providing a conventional meta‐analytic mean (an average weighted on the basis of the precision of the results from each study), we highlight the median effect achieved by included studies, along with an interquartile range for these effects.

The main potential drawback of this method of reporting the median effects of an intervention across a group of studies lies in the equal weight given to all studies (for example no weighting occurs on the basis of study precision). Note, however, that by using the median rather than the mean, the summary estimate is less likely to be driven by a handful of outlying results (such as large effects from small or methodologically poor studies). Moreover, we included an analysis of the impact of study size and various other methodological features on reported effect size. For instance, we compared the median effects across large and small studies (where large was defined as greater than or equal to the median sample size across all included studies). We performed the analysis of potential associations between study size and effect magnitude using various measures of sample size, including the numbers of patients (or episodes of care) without any adjustment for clustering, the effective sample size taking into account cluster effects (using values for intra‐class correlation coefficients available in the published literature (Campbell 2000)) and, finally, using the numbers of providers (or other cluster units) as the sample size.

We also compared the median effects across studies with and without various methodological markers of study quality, as well as certain features of the study context (for example ambulatory versus inpatient setting) and characteristics of the reminders (for example inclusion of patient‐specific information versus a generic alert, provision of an explanation for the reminder, requiring users to enter a response to the reminder before continuing with their work, requiring users to navigate through more than one reminder screen). We made all such comparisons using a non‐parametric rank‐sum test (Mann‐Whitney). We performed all statistical analyses using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

Our search identified 2036 citations, of which 1662 were excluded at the initial stage of screening and an additional 374 on full‐text review, yielding a total of 28 articles that met all inclusion criteria (Figure 4)(Bates 1999; Christakis 2001; Dexter 2001; Eccles 2002a; Filippi 2003; Flottorp 2002; Frank 2004; Hicks 2008; Judge 2006; Kenealy 2005; Kralj 2003 ‐ classified, excluded; Krall 2004; Kucher 2005; McCowan 2001; Meigs 2003; Overhage 1996; Overhage 1997; Peterson 2007; Rothschild 2007; Roumie 2006 ‐ classified, excluded; Safran 1995; Sequist 2005; Tamblyn 2003; Tape 1993; Tierney 2003; Tierney 2005; van Wyk 2008; Zanetti 2003). Four studies contained two comparisons (Eccles 2002a; Flottorp 2002; Kenealy 2005; van Wyk 2008), resulting in 32 included comparisons.

Of the 32 included comparisons, 19 came from US centers and 24 took place in outpatient settings (see 'Characteristics of included studies'). Most (26) trials used a true randomised design, with only six comparisons involving a quasi‐random design (typically allocating intervention status on the basis of even or odd provider identification numbers). Twenty‐six of the 32 included comparisons allocated intervention status at the level of providers or provider groups, rather than allocating patients (i.e. they were cluster trials).

Risk of bias in included studies

Allocation

Of the 32 comparisons in the review, concealed allocation definitely occurred in 14 comparisons (Christakis 2001; Dexter 2001; Flottorp 2002; Frank 2004; Kenealy 2005; McCowan 2001; Meigs 2003; Rothschild 2007; Roumie 2006 ‐ classified, excluded; Safran 1995; van Wyk 2008). The process of allocation concealment was unclear in 14 comparisons (Bates 1999; Eccles 2002a; Filippi 2003; Hicks 2008; Judge 2006; Krall 2004; Overhage 1996; Overhage 1997; Peterson 2007; Sequist 2005; Tierney 2003; Tierney 2005; Tamblyn 2003) and not done in four comparisons (Kralj 2003 ‐ classified, excluded; Kucher 2005; Tape 1993; Zanetti 2003).

Incomplete outcome data

The proportion of eligible practices or providers with complete follow up was reported in 14 comparisons (Christakis 2001; Flottorp 2002; Kenealy 2005; Krall 2004; McCowan 2001; Meigs 2003; Overhage 1997; Rothschild 2007; Roumie 2006 ‐ classified, excluded; Tamblyn 2003; van Wyk 2008). The proportion of eligible patients with complete follow up was reported in 12 comparisons (Filippi 2003; Hicks 2008; Kucher 2005; Meigs 2003; Overhage 1997; Rothschild 2007; Roumie 2006 ‐ classified, excluded; Safran 1995; Tamblyn 2003; Tierney 2003; Tierney 2005; Zanetti 2003). The number of subjects (professionals, practices or patients) lost to follow up was not clear in 11 comparisons (Bates 1999; Dexter 2001; Eccles 2002a; Frank 2004; Judge 2006; Kralj 2003 ‐ classified, excluded; Overhage 1996; Peterson 2007; Sequist 2005; Tape 1993).

Baseline disparities between study groups

Only seven comparisons reported data in a format that permitted calculation of baseline disparities between study groups. Across these studies, the median difference between adherence in the intervention and control groups was 0.00% (interquartile range (IQR): 2.0% greater adherence in the control to 0.0%).

Unit of analysis errors

Of the 26 comparisons with a clustered design, only 12 analysed their results in a manner that took clustering effects into account. Thus, the remaining 14 clustered comparisons exhibited unit of analysis errors.

Other quality criteria

Blinded assessment of study outcomes was generally not relevant, as data were typically derived from electronic systems that documented delivery of the target processes of care. Though not the focus of the review, many of the clinical outcomes were also objective ones, such as laboratory data, and so also did not require blinded assessment.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Of the 32 comparisons that provided analysable results for improvements in process adherence, (Bates 1999; Christakis 2001; Dexter 2001; Eccles 2002a; Filippi 2003; Flottorp 2002; Frank 2004; Hicks 2008; Judge 2006; Kenealy 2005; Kralj 2003 ‐ classified, excluded; Krall 2004; Kucher 2005; McCowan 2001; Meigs 2003; Overhage 1996; Overhage 1997; Peterson 2007; Rothschild 2007; Roumie 2006 ‐ classified, excluded; Safran 1995; Sequist 2005; Tamblyn 2003; Tape 1993; Tierney 2003; Tierney 2005; van Wyk 2008; Zanetti 2003), 21 reported outcomes involving prescribing practices, six specifically targeted adherence to recommended vaccinations, 13 reported outcomes related to test ordering, three captured documentation, and seven reported adherence to miscellaneous other processes (for example composite compliance with a guideline).

Only nine comparisons reported pre‐intervention process adherence for intervention and control groups. For these comparisons, the marginal improvement in the intervention (i.e. the median improvement in the intervention group minus the improvement in the control group) was 3.8% (IQR): 0.4% to 7.9%).

Given the small number of studies that reported baseline adherence, improvements attributable to interventions were calculated as the absolute difference in post‐intervention adherence (i.e. the post‐intervention improvement in the target process of care observed in the intervention group minus that observed in the control group). Using this post‐intervention difference between study groups, the median improvements in process adherence associated with computer reminders were: 4.2 % (IQR: 0.8% to 18.8%) across all process outcomes, 3.3% (IQR: 0.5% to 10.6%) for improvements in prescribing behaviours, 3.8% (IQR: 0.5% to 6.6%) for improvements in vaccination, and 3.8% (IQR: 0.4% to 16.3%) for test ordering behaviours (Table 2). Table 2 also shows the results obtained when we used the outcome with the largest improvement from each study instead of the outcome with the median improvement.

1. Median improvements in process adherence across included studies.

| Dichotomous outcomes (number of intervention vs. control comparisons) | Median absolute improvement (Interquartile range) | |

| Using median outcome from each study | Using best outcome from each study | |

| All process outcomes (N = 32) |

4.2% (0.8% to 18.8%) |

5.6% (2.0% to 19.2%) |

| Prescription of medications (N = 21) |

3.30% (0.5% to 10.6%) |

6.2% (3.0% to 28.0%) |

| Prescription of recommended vaccines (N = 6) |

3.8% (0.5% to 6.6%) |

4.8% (0.5% to 7.8%) |

| Test ordering (N = 13) |

3.8% (0.4% to 16.30%) |

9.6% (0.6% to 24.0%) |

| Elements of recommended documentation (N = 3) |

0.0% (‐1.0% to 1.3%) |

2.0% (2.0% to 4.0%) |

| Other process outcomes (N = 7) |

1.0% (0.8% to 8.5%) |

4.0% (0.8% to 8.5%) |

The Table shows average improvements (expressed as the median and interquartile range) across included comparisons for different types of process outcomes. All process outcomes were defined so that higher values always represent an improvement. For example, data from a study aimed at reducing the percentage of patients receiving inappropriate medications would be captured as the complementary percentage of patients receiving appropriate medications, so that an increase in process adherence would represent an improvement.

Most studies reported multiple endpoints but did not specify a primary outcome. For the main analyses, we used the median improvement from each study (that is the median change in adherence to a target guideline or process of care across all such changes reported for the study) as the single representative outcome for that study. We then calculated the median improvements across all included studies for different types of process measures, as shown in the middle column of the table. The column to the far right presents the same results when we used the best improvement from each study as its representative outcome.

Eight comparisons reported dichotomous clinical endpoints; intervention patients experienced a median absolute improvement of 2.5% (IQR: 1.3% to 4.2%). These endpoints included intermediate endpoints, such as blood pressure and cholesterol targets, as well as clinical outcomes, such as development of pulmonary embolism and mortality. Blood pressure represented the most commonly reported outcome. Patients in intervention groups experienced a median reduction in their systolic blood pressure of 1.0 mmHg (IQR: 2.3 mmHg reduction to 2.0 mmHg increase). For diastolic blood pressure, the median reduction was 0.2 mmHg (IQR: 0.8 mm reduction to 1.0 mm increase).

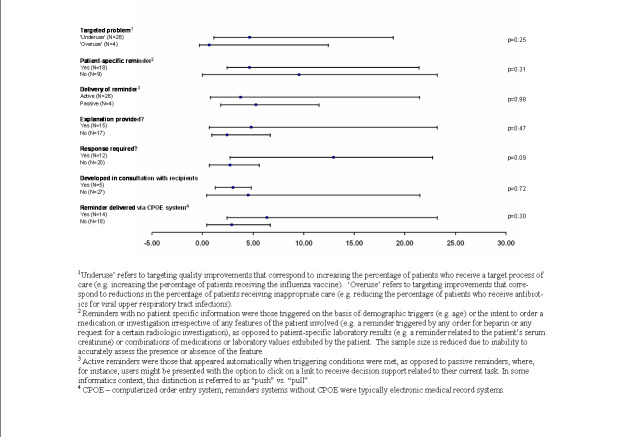

Impacts of study features on effect sizes

There were sufficient comparisons involving process adherence to permit various analyses of potential associations between various study features and the magnitude of effects (Figure 1). The six quasi‐randomised controlled trials reported larger improvements in process adherence than the 26 truly randomised comparisons (7.0%, IQR: 1.2% to 28.0% versus 3.4%: IQR 0.6% to 16.3%), but this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.53). Sample size did not correlate with effect size, whether calculated on the basis of numbers of patients or providers (Figure 1).

1.

Median effects for process adherence by study feature

One might expect studies with low adherence in control groups to report larger improvements in care, but in fact studies with control adherence rates higher than the median across all studies had a non‐significant trend towards larger effect sizes (Figure 1). We analysed the potential impact of baseline adherence in several other ways (for example studies with baseline adherence in top quartile versus all others to look for a ‘ceiling effect’, and studies with baseline adherence in bottom quartile versus all others to look for a floor effect) but found no indication that baseline adherence significantly affected the magnitude of effect in the intervention group.

Interventions that targeted inpatient settings showed a trend towards larger improvements in processes of care than did those that occurred in outpatient settings: 8.7% (IQR: 2.7% to 22.7%) versus 3.0% (0.6% to 11.5%) for outpatient settings (P = 0.34). However, all interventions delivered in inpatient settings occurred at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston or the Regenstreif Institute at the University of Indiana. Both of these institutions have mature ‘homegrown’ computerized provider order entry systems, and the recipients of computer reminders from these institutions consisted primarily of physician trainees, either of which factors may be more relevant than the fact of the inpatient setting.

Studies from the US reported slightly larger improvements in process adherence: 5.0% (IQR: 2.0% to 23.2%) versus 1.2% (IQR: 0.4% to 6.2%) for non‐US studies), but this difference was not significant (P = 0.12). Moreover, this trend at least partly reflected the results of studies from US institutions with long track records with clinical information systems (for example the Regenstreif Institute and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston).

Grouping studies on the basis of track records in clinical informatics (for example analysing studies from Brigham and Women’s Hospital, the Regenstreif Institute and Vanderbilt University versus all others) did not result in significant differences, except in the case of Brigham and Women’s Hospital. The four studies from Brigham and Women’s Hospital by themselves reported significantly higher improvements in process adherence than all other studies: 16.8% (IQR: 8.7% to 26.0%) versus 3.0% (IQR: 0.5% to 11.5%; P = 0.04).

Lastly, the magnitude of effects attributable to computer reminders appeared to vary with the presence of co‐interventions (delivered to intervention and control groups). The 32 comparisons that reported process adherence outcomes included 18 that evaluated a computer reminder versus usual care and 14 that evaluated a computer reminder plus at least one other quality improvement intervention (for example educational materials) versus this same co‐intervention in the control group. Comparisons involving no co‐interventions (that is computer reminder alone versus usual care) showed a median improvement in process adherence of 5.7% (IQR: 2.0% to 24.0%), whereas studies of multifaceted interventions (that is computer reminders plus additional interventions versus those additional interventions alone) showed a median improvement in adherence of only 1.9% (IQR: 0.0% to 6.2%; P = 0.04 for this difference).

This apparent difference might reflect a ceiling effect, with co‐interventions delivered to the intervention and control groups leaving little room for computer reminders to demonstrate additional improvements. If this were the case, one would expect higher post‐intervention adherence rates in the control groups of studies that combined computer reminders with other interventions. However, the opposite proved true: post‐intervention values for process adherence (in both intervention and control groups) were in fact slightly higher in the studies involving comparisons of computer reminders by themselves, not in the studies involving additional interventions.

This relationship between comparison type and effect size at least partially reflected confounding by other studies features. For instance, dropping the four studies from Brigham and Women’s Hospital from the analysis substantially decreased the magnitude of the difference between studies with and without co‐interventions (median improvement of 0.9%, IQR: 0.0% to 5.0% versus 3.8%, IQR: 1.2% to 23.2%), and the difference was no longer statistically significant (P = 0.08). Also, of note, none of the P values reported in the analysis adjusted for multiple comparisons nor was stratification by the presence of co‐interventions a pre‐specified hypothesis for our analysis, further adding to the possibility that the observed difference reflects a chance association.

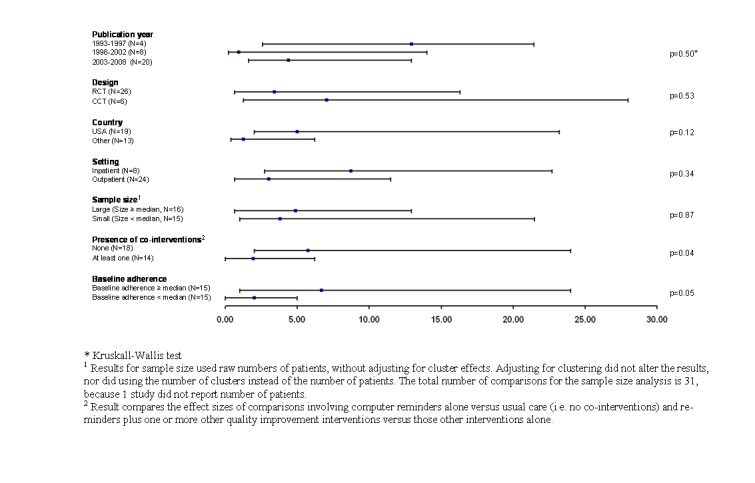

Features of computer reminders

We analysed a number of characteristics of the computer reminders (or the larger clinical information system) to look for associations with the magnitude of impact (Figure 2). The degree of improvement did not differ significantly between studies based on the type of quality problem targeted (underuse versus overuse of a given process of care), the conveyance of patient‐specific information versus a more generic alert, provision of an explanation for the alert, whether or not the reminder conveyed a specific recommendation, whether or not the authors of the study had developed the reminder, or the type of system used to deliver the reminder (CPOE versus electronic medical record).

2.

Median effects for process adherence by reminder feature

There was a trend towards larger effects with reminders that required users to enter a response of some kind (12.9%, IQR 2.7% to 22.7%) versus those that did not (2.7%, IQR: 0.6% to 5.6%; P = 0.09). However, this trend was confounded by the fact that all four comparisons from Brigham and Women's Hospital involved reminders that required responses from users. Dropping these four studies decreased the median effect of reminders that required user responses to 10.6% (IQR: 0.3% to 21.4%) and removed any appearance of statistical significance (P = 0.48). Of note, though, the magnitude of the difference remains substantial (10.6% versus 2.7%); it is possible that the lack of significance reflects lack of power.

We also analysed whether effect sizes differed between reminders that were 'pushed' onto users (that is users automatically received the reminder) versus reminders that required users to perform some action to receive it (that is users had to 'pull' the reminders). Only four comparisons involved 'pull' reminders and these showed comparable effects to 'push' reminders. Of note, however, one trial (van Wyk 2008) directly compared these two modes of reminder delivery. In this three‐armed cluster‐RCT of reminders for screening and treatment of hyperlipidemia, patients cared for at practices randomised to automatic alerts were more likely to undergo testing for hyperlipidemia and receive treatment than were patients seen at clinics where reminders were delivered to clinicians only ‘on‐demand.’

Sensitivity analysis

We reanalysed the potential predictors of effect size (study features and characteristics of the reminders) using a variety of alternate choices for the representative outcome from each study, including the outcome with the middle value (rather than a calculated median) and the best outcome (that is the outcome associated with the largest improvement in process adherence). None of these analyses substantially altered the main findings, including the lack of any significant association between study or reminder features and the magnitude of effects achieved by computer reminders. Of note, using the best outcome from each study rather than the median outcome, improvements attributable to reminders in studies at Brigham and Womens Hospital were no longer significantly larger than those achieved in studies from other centers (16.8%, IQR: 8.7% to 26.0% versus 4.6%, IQR: 2.0% to 13.4%; P = 0.09 for the comparison). However, the difference still appears large, so loss of significance may simply reflect the lack of power.

Discussion

Across 32 comparisons, computer reminders achieved small to modest improvements in care. The absolute improvement in process adherence was less than 4% for half of the included comparisons. Even when we included the best outcome from each comparison, the median improvement was only 5.6%. For improvements in prescribing, perhaps the behaviours of greatest general interest, improvements were even smaller.

With the upper quartile of reported improvements beginning at a 15% increase in process adherence, some studies clearly did show larger effects. However, we were unable to identify any study or reminder features that predicted larger effect sizes, except for a statistically significant (albeit unadjusted for multiple comparisons) difference in effects seen in studies involving the computer order entry system at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. A trend towards larger effects was seen for reminders that required users to enter a response in order to proceed, but this finding may have been confounded by the uneven distribution of studies from Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Thus, we do not know if the success of computer reminders at the Brigham partially reflects the design of reminders requiring user responses or if other features of the computer system or institutional culture of Brigham play the dominant role.

The finding that comparisons of computer reminders alone versus usual reported larger effect sizes than comparisons involving computer reminders and other co‐interventions represented an unexpected finding. Exploratory analyses did not reveal a plausible explanation for this result except that it may have reflected uneven distribution of confounders. One additional explanation might be that investigators chose to incorporate computer reminders in multifaceted interventions when attempting to change more complex (and therefore difficult to change) behaviours than those addressed by reminders alone. However, this unexpected finding may also constitute a chance association, especially as none of the P values reported in the analysis adjust for multiple comparisons.

A major potential limitation of our analysis was the heterogeneity of the interventions and the variable degree with which they were reported, including limited descriptions of key intervention features of the reminders and the systems through which they were delivered. We attempted to overcome this problem by abstracting basic attributes, such as whether user responses were required and whether or not the reminder contained patient‐specific information, but heterogeneity within even these apparently straightforward categories could mask important differences in effects. Also, other characteristics which we found difficult to operationalise for example the 'complexity' of the reminder), or which were inadequately reported, may also correlate with important differences in impact. This problem of limited descriptive detail of complex interventions and the resulting potential for substantial heterogeneity among included interventions in systematic reviews has been consistently encountered in the literature (Grimshaw 2003; Ranji 2008; Shojania 2005; Walsh 2006).

Our focus on the median effects across studies represents another potential limitation. However, as outlined in the 'Methods' section, we chose this approach precisely to avoid spurious precision due to heterogeneity and clustering effects that could not be taken into account in many studies. This approach is becoming increasingly common in Cochrane Reviews of interventions to change practice (Grimshaw 2004; Jamtvedt 2006; O'Brien 2007) and has also been used in other evidence syntheses (Grimshaw 2004; Shojania 2004b; Steinman 2006; Walsh 2006). This method conveys the range of effects associated with the intervention of interest and also allows for analysis of factors associated with effect size.

Additional studies continue to appear and we plan to assess eligible new studies formally for inclusion in six months. At that time we will also include a study that had previously been excluded as a time series, but which we have since decided merits inclusion as a controlled clinical trial (Durieux 2000 ‐ classified, excluded).

In summary, computer reminders delivered at the point of care have achieved variable improvements in target behaviours and processes of care. The small to modest median effects shown in our analysis may hide larger effects. However, the current literature does not suggest which features of the reminder systems, the systems with which they are delivered, or which target problems might consistently predict larger improvements.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

On‐screen computer reminders may become more prevalent as healthcare institutions advance in the use of computer technology. There appears to be a wide range of effects of the intervention, making it difficult to provide specific suggestions about how to maximize the benefits.

Implications for research.

Although some studies have clearly shown substantial improvements in care from point of care computer reminders it is concerning that the majority of studies have shown fairly small improvements across a range of process types. This finding of small to modest improvements is not unique to computer reminders. As had been said before, there are no 'magic bullets' when it comes to changing provider behavior and improving care (Shojania 2005; Oxman 1995). However, given that the opportunity to deliver computer reminders at the point of care represents one of the major incentives to implementing sophisticated clinical information systems, future research will need to identify key factors (related to the target quality problem or the design of the reminder) that reliably predict larger improvements in care from these expensive technologies.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 15 June 2021 | Review declared as stable | A related systematic review was published in September 2020 (https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m3216) and consequently there are no current plans to update this Cochrane Review. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 1998 Review first published: Issue 3, 2009

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 7 December 2010 | Amended | Minor typo change to title |

| 11 November 2009 | Amended | Minor changes to figures |

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the assistance of Naghmeh Mojaverian and Jun Ji for their assistance with data extraction on this review. We would also like to acknowledge the assistance of Kathleen McGovern in preparing the review for publication. We would also like to acknowledge the contributions of Richard Gordon, Jeremy Wyatt and Rachel Rowe on the protocol for this review. Finally, we would like to thank Pierre Durieux, Richard Shiffman, Tomas Pantoja and Michelle Fiander for their helpful comments on earlier versions of this review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE search strategy

Strategy 1 (OVID)

1 "Forms and Records Control"/ 2 exp "Appointments and Schedules"/ 3 Medical Records Systems, Computerized/ 4 exp Decision Making, Computer‐Assisted/ 5 exp Artificial Intelligence/ 6 or/1‐5 7 Reminder Systems/ 8 (reminder$ or prompt$ or cue).tw. 9 or/7‐8 10 6 and 9 11 7 or 10 12 computer$.tw,hw. 13 11 and 12 14 (computer$ adj3 reminder$).tw. 15 or/13‐14 16 randomized controlled trial.pt. 17 controlled clinical trial.pt. 18 randomized controlled trials/ 19 random allocation/ 20 double blind method/ 21 single blind method/ 22 clinical trial.pt. 23 exp clinical trials/ 24 (clinical adj trial?).tw. 25 ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$)).tw. 26 (random$ or placebo?).tw. 27 or/16‐26 28 animal/ 29 human/ 30 28 not (28 and 29) 31 27 not 30 32 15 and 31

Strategy 2 (PubMed)

#1 Search Ambulatory Care Information Systems [mh] OR Point‐of‐Care Systems [mh] OR Medical Order Entry Systems [mh] OR decision support systems, clinical [mh] OR drug therapy, computer‐assisted [mh] OR Medical Records Systems, Computerized [mh] OR Reminder Systems [mh] OR ((computer* [ti] OR electronic [ti]) AND (decision* [ti] OR support [ti] OR order* [ti] OR entry [ti] OR reminder* [ti] or prompt* [ti] or cue* [ti] OR alert* [ti])) #2 Search ((Randomised [ti] OR Randomized [ti] OR Controlled [ti] OR intervention [ti] OR evaluation [ti] OR Comparative [ti] OR effectiveness [ti] OR Evaluation [ti] OR Feasibility [ti]) AND (trial [ti] OR Studies [ti] OR study [ti] OR Program [ti] OR Design [ti])) OR Clinical Trial [pt] OR Randomized Controlled Trial [pt] #3 Search #1 and #2, Limits: English

Appendix 2. EPOC Register search strategy

[limit to RCT and CCT, 2005 ‐]

((reminder* or prompt* or cue*) and (computer* or on‐screen))

Appendix 3. CINAHL search strategy

1 exp Medical Records/ 2 ((form? or record?) adj (medical or control)).tw. 3 "Appointments and Schedules"/ 4 exp Patient Records Systems/ 5 exp Decision Making, Computer‐Assisted/ 6 exp Artificial Intelligence/ 7 artificial intelligence.tw. 8 natural language processing.tw. 9 or/1‐8 10 Reminder System/ 11 (reminder$ or prompt$ or cue).tw. 12 or/10‐11 13 9 and 12 14 10 or 13 15 computer$.tw,hw. 16 14 and 15 17 (computer$ adj3 reminder$).tw. 18 16 or 17 19 exp clinical trials/ 20 comparative studies/ 21 (clinical adj trial?).tw. 22 (random$ or placebo?).tw. 23 ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$)).tw. 24 exp quasi‐experimental studies/ 25 or/19‐24 26 18 and 25

Appendix 4. EMBASE search strategy

1 Medical Record/ 2 ((form? or record?) adj (medical or control)).tw. 3 (patient? adj3 (schedul$ or appointment?)).tw. 4 (computer$ adj (medical or record?)).tw. 5 Computer Analysis/ 6 (decision? adj2 computer‐assisted).tw. 7 exp Artificial Intelligence/ 8 artificial intelligence.tw. 9 natural language processing.tw. 10 or/1‐9 11 Reminder System/ 12 (reminder$ or prompt$ or cue).tw. 13 or/11‐12 14 10 and 13 15 11 or 14 16 computer$.tw,hw. 17 15 and 16 18 (computer$ adj3 reminder$).tw. 19 17 or 18 20 Randomized Controlled Trial/ 21 (random$ or placebo?).tw. 22 clinical trial/ 23 (clinical adj trial?).tw. 24 ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$)).tw. 25 or/20‐24 26 19 and 25

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. CDSS (+/‐ co‐intervention) vs. Usual care (+/‐ co‐intervention).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 All | 114 | 935192 | Risk Difference (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.07 [0.06, 0.09] |

| 1.2 Prescription | 64 | 276410 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.16 [1.12, 1.20] |

| 1.3 Vaccination | 11 | 66725 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.51 [1.29, 1.77] |

| 1.4 Testing | 30 | 212791 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.20 [1.12, 1.29] |

| 1.5 Documentation | 25 | 539528 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.75 [1.48, 2.07] |

| 1.7 Other | 32 | 300114 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.63 [1.47, 1.81] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: CDSS (+/‐ co‐intervention) vs. Usual care (+/‐ co‐intervention), Outcome 1: All

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: CDSS (+/‐ co‐intervention) vs. Usual care (+/‐ co‐intervention), Outcome 2: Prescription

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: CDSS (+/‐ co‐intervention) vs. Usual care (+/‐ co‐intervention), Outcome 3: Vaccination

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: CDSS (+/‐ co‐intervention) vs. Usual care (+/‐ co‐intervention), Outcome 4: Testing

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: CDSS (+/‐ co‐intervention) vs. Usual care (+/‐ co‐intervention), Outcome 5: Documentation

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1: CDSS (+/‐ co‐intervention) vs. Usual care (+/‐ co‐intervention), Outcome 7: Other

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Abdel‐Kader 2011.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | Cluster RCT | |

| Participants | University‐based outpatient general internal medicine practice, USA 248 patients, 30 providers |

|

| Interventions | Two reminders that were activated for patients with moderate to advanced chronic kidney disease (one suggested a referral to a nephrologist, a second suggested albumin quantification if not done within prior year) | |

| Outcomes | Process adherence (testing, documentation, other), clinical endpoint (laboratory test results, e.g. creatinine, hemoglobin) | |

| Co‐Interventions | Educational: Multiple (>1) educational sessions for providers in both control and intervention groups Beyond Clinician Education: None |

|

| CDSS Features ‐ Acknowledgement of CDSS Required | No | |

| CDSS Features ‐ Other | Considered alert fatigue in design, conveyed patient‐specific information, makes care recommendation, possible to execute desired action, 'push' mode of delivery, targeted underuse | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Baseline characteristics similar? | Low risk | |

| Unit of analysis error | Low risk | |

Ansari 2003.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | Cluster RCT | |

| Participants | Academically affiliated medical center, San Francisco, USA (San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center) 115 patients, 49 providers of primary care for patients with congestive heart failure |

|

| Interventions | CDSS encouraging beta‐blocker use in eligible patients with heart failure | |

| Outcomes | Process adherence (prescribing), clinical endpoint (three outcomes related to hospitalization, mortality) | |

| Co‐Interventions | Educational: Distribution of educational materials and multiple (>1) educational sessions for providers in both control and interventions groups Beyond Clinician Education: Provision of list of patients eligible for beta‐blocker therapy, patient letter encouraging discussion of beta‐blocker therapy with provider in intervention group |

|

| CDSS Features ‐ Acknowledgement of CDSS Required | Not reported | |

| CDSS Features ‐ Other | Conveyed patient‐specific information, makes care recommendation, 'push' mode of delivery, targeted underuse | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | N/A |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Baseline characteristics similar? | Low risk | |

| Unit of analysis error | Low risk | |

Arts 2017.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | Cluster RCT | |

| Participants | General practice clusters, the Netherlands 781 patients, 39 general practitioners across 18 practices |

|

| Interventions | CDSS determined recommended stroke prevention treatment based on patient risk status and informed the provider of discrepancies between current and recommended treatment | |

| Outcomes | Process adherence (other) | |

| Co‐Interventions | Educational: None Beyond Clinician Education: None |

|

| CDSS Features ‐ Acknowledgement of CDSS Required | No | |

| CDSS Features ‐ Other | Ambush, considered alert fatigue in design, conveyed patient‐specific information, decision support was complex, developed by study investigators, included supporting information on‐screen, makes care recommendation, other concurrent CDSS, 'push' mode of delivery, targeted overuse and underuse, user workflow considered in design | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Baseline characteristics similar? | Low risk | |

| Unit of analysis error | Low risk | |

Awdishu 2016.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | Cluster RCT | |

| Participants | Inpatient and outpatient settings of academic medical center, San Diego, USA (University of California, San Diego) 1278 patients, 514 providers |

|

| Interventions | CDSS monitoring patient creatinine clearance and notifying physicians of necessity for renal dose adjustment or discontinuation of medications for patients with impaired renal function | |

| Outcomes | Process adherence (prescribing) | |

| Co‐Interventions | Educational: None Beyond Clinician Education: None |

|

| CDSS Features ‐ Acknowledgement of CDSS Required | Yes – required acknowledgment of the CDSS but not documentation of action taken | |

| CDSS Features ‐ Other | Conveyed patient‐specific information, decision support was complex, developed by study investigators, makes care recommendation, possible to execute desired action, 'push' mode of delivery, user workflow considered in design | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Baseline characteristics similar? | Low risk | |

| Unit of analysis error | Low risk | |

Baandrup 2010.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | Cluster CCT | |

| Participants | Two municipalities, Denmark 602 patients |

|

| Interventions | Reminder that popped up every time antipsychotic polypharmacy was about to be prescribed | |

| Outcomes | Process adherence (prescribing) | |

| Co‐Interventions | Educational: Multiple (>1) educational sessions for providers in intervention group Beyond Clinician Education: None |

|

| CDSS Features ‐ Acknowledgement of CDSS Required | Not reported | |

| CDSS Features ‐ Other | Conveyed patient‐specific information, 'push' mode of delivery, targeted overuse | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | N/A |

| Baseline characteristics similar? | Low risk | |

| Unit of analysis error | High risk | |

Baer 2013.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | Cluster CCT | |

| Participants | Primary care clinics affiliated with regional academic medical network, USA (Partners HealthCare System) 15 495 patients, 5 practices |

|

| Interventions | Patient self‐administered web‐based risk appraisal tool completed in waiting area that sends patient‐entered information on family history of cancer to electronic health record for clinicians to view. If accepted, populates coded fields and generates reminders about colon and breast cancer screening based on familial risk. | |

| Outcomes | Process adherence (documentation) | |

| Co‐Interventions | Educational: Distribution of educational materials to providers in intervention group Beyond Clinician Education: None |

|

| CDSS Features ‐ Acknowledgement of CDSS Required | Not reported | |

| CDSS Features ‐ Other | Developed by study investigators, makes care recommendation | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | N/A |

| Baseline characteristics similar? | Low risk | |

| Unit of analysis error | Low risk | |

Bates 1999.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | All inpatients at academic medical center, Boston, USA (Brigham and Women’s Hospital) 939 episodes of care |

|

| Interventions | Reminder that was generated at the time a test that appeared to be redundant was ordered, prompting providers to consider cancelling the test | |

| Outcomes | Process adherence (testing) | |

| Co‐Interventions | Educational: None Beyond Clinician Education: None |

|

| CDSS Features ‐ Acknowledgement of CDSS Required | Yes ‐ required acknowledgement of the CDSS and documentation of action taken | |

| CDSS Features ‐ Other | Conveyed patient‐specific information, included supporting information on‐screen, interruptive, makes care recommendation, possible to execute desired action, 'push' mode of delivery, targeted overuse | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Baseline characteristics similar? | Low risk | |

Beeler 2014.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | Cluster RCT | |

| Participants | Academic medical center, Switzerland (University Hospital Zurich) 15 736 patients, 6 departments |

|

| Interventions | CDSS displayed for patients who did not receive a thromboprophylaxis order within the first 6h of admission or transfer. To improve specificity, he algorithm checked for thromboprophylaxis orders that were active within the 0–30h time frame after admission or transfer. | |

| Outcomes | Process adherence (prescribing), clinical endpoint (four outcomes pertaining to bleeding, heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia, venous thromboembolism) | |

| Co‐Interventions | Educational: None Beyond Clinician Education: None |

|

| CDSS Features ‐ Acknowledgement of CDSS Required | No | |

| CDSS Features ‐ Other | Considered alert fatigue in design, conveyed patient‐specific information, makes care recommendation, other concurrent CDSS, 'push' mode of delivery, targeted underuse, user workflow considered in design | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | N/A |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Baseline characteristics similar? | Low risk | |

| Unit of analysis error | High risk | |

Bell 2010.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | Cluster RCT | |

| Participants | Primary care practice‐based research network, USA (Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Pediatric Research Consortium) 19 450 patients, 12 practices |

|

| Interventions | Decision support for patients with asthma to improve adherence to national guidelines, including data‐entry tool, standardized documentation templates, order sets, and action/care plan for families | |

| Outcomes | Process adherence (prescribing, documentation, other) | |

| Co‐Interventions | Educational: Education session for providers in both intervention and control groups Beyond Clinician Education: None |

|

| CDSS Features ‐ Acknowledgement of CDSS Required | No | |

| CDSS Features ‐ Other | Appearance differed based on urgency, conveyed patient‐specific information, makes care recommendation, possible to execute desired action, 'push' mode of delivery, targeted underuse | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | N/A |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | N/A |

| Baseline characteristics similar? | Low risk | |

| Unit of analysis error | Low risk | |

Bennett 2018.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | ||

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Co‐Interventions | ||

| CDSS Features ‐ Acknowledgement of CDSS Required | ||

| CDSS Features ‐ Other | ||

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Baseline characteristics similar? | Low risk | N/A |

Bernstein 2017.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | Cluster RCT | |

| Participants | Internal medicine units, two academic medical centers, New Haven, USA (Yale New Haven Hospital and unnamed) 19 902 patients, 254 physicians |

|

| Interventions | Prompts physicians to refer smoking patients to a quitline, order tobacco cessation therapies, and document the patients’ smoking status | |

| Outcomes | Process adherence (prescribing, documentation, other) | |

| Co‐Interventions | Educational: Single educational session for providers in intervention group Beyond Clinician Education: Audit and feedback in intervention group |

|

| CDSS Features ‐ Acknowledgement of CDSS Required | Yes – required acknowledgment of the CDSS but not documentation of action taken | |

| CDSS Features ‐ Other | Ambush, considered alert fatigue in design, conveyed patient‐specific information, developed by study investigators, interruptive, makes care recommendation, possible to execute desired action, 'push' mode of delivery, required provider input of clinical data, targeted underuse, user workflow considered in design | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | N/A |

| Baseline characteristics similar? | Unclear risk | N/A |

| Unit of analysis error | Low risk | |

Beste 2015.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | Cluster RCT | |

| Participants | Eight VA facilities in the Pacific Northwest, USA 2884 patients |

|

| Interventions | CDSS intended to improve hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance by reminding clinicians to perform liver ultrasounds for patients with cirrhosis who had not received surveillance in the preceding 6 months | |

| Outcomes | Process adherence (testing, other) | |

| Co‐Interventions | Educational: None Beyond Clinician Education: None |

|

| CDSS Features ‐ Acknowledgement of CDSS Required | Yes ‐ required acknowledgement of the CDSS and documentation of action taken | |

| CDSS Features ‐ Other | Considered alert fatigue in design, conveyed patient‐specific information, developed by study investigators, included supporting information on‐screen, makes care recommendation, other concurrent CDSS, possible to execute desired action, 'push' mode of delivery, targeted underuse, user workflow considered in design | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | N/A |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Baseline characteristics similar? | Low risk | |

| Unit of analysis error | High risk | |

Boustani 2012.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | General medical ward, academic medical center, Indianapolis, USA (Wishard Memorial Hospital) 424 patients |

|

| Interventions | Reminder notifying physicians of presence of cognitive impairment, recommending early geriatric consultation, and suggesting discontinuation of urinary catheterization, physical restraints, and anticholinergic drugs | |

| Outcomes | Process adherence (prescribing, other), clinical endpoint (30‐day mortality, 30‐day readmission, hospital adverse event, mean length of hospital stay, home discharge) | |

| Co‐Interventions | Educational: None Beyond Clinician Education: None |

|

| CDSS Features ‐ Acknowledgement of CDSS Required | Yes ‐ required acknowledgement of the CDSS and documentation of action taken | |

| CDSS Features ‐ Other | Conveyed patient‐specific information, developed by study investigators, interruptive, makes care recommendation, other concurrent CDSS, 'push' mode of delivery, targeted overuse | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | N/A |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Baseline characteristics similar? | Low risk | |

Campbell 2019.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | ||

| Participants | ||

| Interventions | ||

| Outcomes | ||

| Co‐Interventions | ||

| CDSS Features ‐ Acknowledgement of CDSS Required | ||

| CDSS Features ‐ Other | ||

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Baseline characteristics similar? | Low risk | |

Chak 2018.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | RCT | |