ABSTRACT

Cryptococcus neoformans strains isolated from patients with AIDS secrete acid phosphatase, but the identity and role of the enzyme(s) responsible have not been elucidated. By combining a one-dimensional electrophoresis step with mass spectrometry, a canonically secreted acid phosphatase, CNAG_02944 (Aph1), was identified in the secretome of the highly virulent serotype A strain H99. We created an APH1 deletion mutant (Δaph1) and showed that Δaph1-infected Galleria mellonella and mice survived longer than those infected with the wild type (WT), demonstrating that Aph1 contributes to cryptococcal virulence. Phosphate starvation induced APH1 expression and secretion of catalytically active acid phosphatase in the WT, but not in the Δaph1 mutant, indicating that Aph1 is the major extracellular acid phosphatase in C. neoformans and that it is phosphate repressible. DsRed-tagged Aph1 was transported to the fungal cell periphery and vacuoles via endosome-like structures and was enriched in bud necks. A similar pattern of Aph1 localization was observed in cryptococci cocultured with THP-1 monocytes, suggesting that Aph1 is produced during host infection. In contrast to Aph1, but consistent with our previous biochemical data, green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged phospholipase B1 (Plb1) was predominantly localized at the cell periphery, with no evidence of endosome-mediated export. Despite use of different intracellular transport routes by Plb1 and Aph1, secretion of both proteins was compromised in a Δsec14-1 mutant. Secretions from the WT, but not from Δaph1, hydrolyzed a range of physiological substrates, including phosphotyrosine, glucose-1-phosphate, β-glycerol phosphate, AMP, and mannose-6-phosphate, suggesting that the role of Aph1 is to recycle phosphate from macromolecules in cryptococcal vacuoles and to scavenge phosphate from the extracellular environment.

IMPORTANCE

Infections with the AIDS-related fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans cause more than 600,000 deaths per year worldwide. Strains of Cryptococcus neoformans isolated from patients with AIDS secrete acid phosphatase; however, the identity and role of the enzyme(s) are unknown. We have analyzed the secretome of the highly virulent serotype A strain H99 and identified Aph1, a canonically secreted acid phosphatase. By creating an APH1 deletion mutant and an Aph1-DsRed-expressing strain, we demonstrate that Aph1 is the major extracellular and vacuolar acid phosphatase in C. neoformans and that it is phosphate repressible. Furthermore, we show that Aph1 is produced in cryptococci during coculture with THP-1 monocytes and contributes to fungal virulence in Galleria mellonella and mouse models of cryptococcosis. Our findings suggest that Aph1 is secreted to the environment to scavenge phosphate from a wide range of physiological substrates and is targeted to vacuoles to recycle phosphate from the expendable macromolecules.

INTRODUCTION

Cryptococcus neoformans is an opportunistic fungal pathogen that predominantly infects immunocompromised hosts, is responsible for more than 600,000 deaths per year, and is the most common cause of fungal meningitis worldwide. Infection is established in the lung following inhalation of infectious propagules and spreads to the central nervous system (CNS) via the bloodstream, causing life-threatening meningoencephalitis.

Proteins secreted by C. neoformans are key mediators of host-pathogen interactions during the various stages of infection and represent potential diagnostic markers and/or therapeutic targets. Phospholipase B1 (Plb1) and laccase are two well-characterized virulence factors that are canonically secreted by C. neoformans but also reside at the membrane and/or cell wall following their transport through the secretory pathway (1–6). Extracellular acid phosphatase (APase) is produced by a large majority of C. neoformans strains (predominantly serotype A) isolated from patients with AIDS (7), by other fungal pathogens, including Candida species (8, 9), Sporothrix schenckii (10), and Aspergillus fumigatus (11), by pathogenic bacteria (12), and by protozoa (13, 14). Acid phosphatases have also been reported to facilitate adhesion of C. neoformans to host cells (15). However, the enzyme(s) responsible for this activity in C. neoformans has not been identified.

Secreted acid phosphatases hydrolyze phosphomonoester metabolites, releasing inorganic phosphate (Pi). The subsequent uptake of Pi by fungal cells is then used to maintain intracellular phosphate homeostasis (11, 16–18). Intracellular Pi is essential for the synthesis of macromolecules, including ATP, phospholipids, and proteins, and is involved in numerous signaling and metabolic processes (for a review, see reference 19). In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Pi homeostasis is regulated by the Pi signal transduction (PHO) pathway, which is comprised of multiple Pi-responsive enzymes, including extracellular acid phosphatase Pho5, Pi transporters, and alkaline phosphatases. Pho5 has been used extensively as a reporter to study the mechanism of Pi sensing in S. cerevisiae (20, 21). The genome of C. neoformans contains homologues of the S. cerevisiae PHO pathway components, including a putative secreted Pho5 homologue, CNAG_02944. However, the regulation and function of this enzyme are still unknown.

In all eukaryotes, secretion occurs via canonical and noncanonical pathways, although in fungi, distal convergence of these pathways may occur (22). Noncanonical secretion routes bypass the Golgi apparatus, with some relying on multivesicular bodies for externalization of cargo packaged into exosome-like vesicles (23). In the secretomes of several pathogenic fungi, including Candida albicans and Paracoccidioides species, noncanonically secreted proteins represent a significant proportion of the total secreted protein pool (24, 25).

Canonically secreted proteins contain a signal peptide (SP), which targets them to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) for folding and glycosylation and acquisition of a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor (as in the case of Plb1 [2, 3]). From the ER, these proteins are transported to the trans-Golgi-network (TGN), where their sugar chains are modified. From the TGN, protein cargo is packaged within secretory vesicles. These secretory vesicles are then transported directly to the plasma membrane or indirectly via endosomes to the plasma membrane or vacuoles (e.g., hydrolytic enzymes).

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the formation of secretory vesicles in the TGN involves coordination of the activity of proteins involved in vesicle formation with lipid metabolism by an essential phosphatidylinositol (PI) transfer protein, Sec14 (for review, see reference 26). Sec14 has been reported to regulate the vesicular traffic of enzymes with acid phosphatase activity from the Golgi apparatus to the plasma membrane via endosomes and of carboxypeptidase Y from the Golgi apparatus to the vacuole (27). We recently identified a functional homologue of Sec14 in C. neoformans, designated CnSec14-1 (28). Deletion of CnSEC14-1 led to attenuated virulence in mice and reduced secretion of canonically secreted Plb1 (28).

To date there have been only three published reports, all using acapsular C. neoformans serotype D mutant strains, for which proteomic analysis was utilized to identify the composition of the C. neoformans secretome: Eigenheer et al. (29) and Biondo et al. (30) identified 29 and 12 extracellular proteins, respectively, while Rodrigues et al. (23) identified 76 proteins that were specifically associated with exosome-like vesicles. We performed a proteomic analysis on secretions obtained from the more-virulent encapsulated serotype A strain of C. neoformans, H99, and identified CNAG_02944 (designated Aph1) as the acid phosphatase responsible for the extracellular acid phosphatase activity previously observed by others (7, 15). Via the creation of an APH1 deletion mutant (Δaph1) and a wild-type (WT) strain expressing DsRed-tagged Aph1, we characterized the mode of Aph1 induction and secretion, the substrate specificity of the enzyme, and its contribution to cellular function and virulence by using well-accepted models of cryptococcosis.

RESULTS

Acid phosphatase Aph1 is a component of the secretome of strain H99.

We identified 105 proteins in the H99 secretome by using mass spectrometry (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). This is a higher number than reported previously (29, 30); using a shotgun approach, our group similarly identified only 26 proteins, none of which was an acid phosphatase. We attribute the greatly improved protein discrimination in the present study to removal of interfering free capsular polysaccharides from protein preparations by the inclusion of an SDS-PAGE purification step. Twenty-seven proteins (26%) identified in the H99 secretome were predicted to follow the canonical route of export from the cell (see Table S1), including three associated with virulence, which have never been directly identified in cryptococcal secretomes via mass spectrometry: Plb1, laccase, and α-1,3-glucan synthase. Some proteins, including α-amylase, chitin deacetylase, glyoxal oxidase, 1,3-β-glucanosyltransferase, carboxylesterase, and aspartic protease, were previously identified as extracellular proteins of a serotype D acapsular mutant (29). All proteins were categorized according to function and mode of secretion (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). A canonically secreted acid phosphatase encoded by CNAG_02944 was also identified for the first time in a serotype A secretome, and this protein was named Aph1.

Characterization of extracellular Aph1.

The genome of C. neoformans var. grubii encodes four predicted acid phosphatases (CNAG_02944 [APH1], CNAG_02681, CNAG_06967, and CNAG_06115). Only one of these enzymes, Aph1, is predicted to be secreted and was identified in our proteomic analysis (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Sequence analysis and in silico structural modeling suggested that Aph1 belongs to branch 2 of the histidine acid phosphatases and is most similar to fungal phytases (phytic acid-degrading enzymes) (31). CNAG_02681 and CNAG_06967 also belong to the same branch, despite the absence of a leader peptide. Aph1 and its closest homologue, CNAG_06967, share 33% identity at the amino acid level. To investigate the contribution of Aph1 to the total pool of extracellular acid phosphatase activity in the WT and to cryptococcal pathogenicity, an APH1 gene deletion mutant (Δaph1) was created.

Role of extracellular Aph1 in fungal virulence.

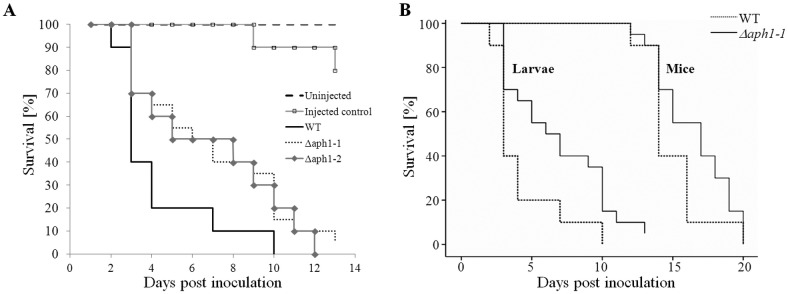

In vitro, growth of Δaph1 was similar to that of WT at 30°C and 37°C and in the presence of cell wall-perturbing agents. In addition, similar levels of melanization and capsule were produced (data not shown). Despite the WT-like phenotype in vitro, APH1 deletion affected survival when tested in a Galleria mellonella infection model. G. mellonella larvae were inoculated with WT and two independent Δaph1 mutants (Δaph1-1 and Δaph1-2) by using an infection dose of 106 fungal cells per larva. Larvae infected with Δaph1-1 or Δaph1-2 mutant strains survived longer (median survival of 6 and 5 days, respectively) than WT-infected larvae (median survival of 3 days) (Fig. 1A). Although survival curves of both Δaph1 strains in G. mellonella were similar, only the difference in survival of Δaph1-1 (n = 20) and WT-infected larvae (n = 10) was statistically significant (P = 0.028). The P value for the Δaph1-2 (n = 10) and WT (n = 10) comparison was 0.062.

FIG 1 .

Aph1 contributes to cryptococcal virulence in G. mellonella and mouse infection models. (A) G. mellonella larvae were inoculated with 106 cells of WT and Δaph1-1 and Δaph1-2 mutant strains. Uninjected larvae and those injected with water served as controls. The larvae were incubated at 30°C for 10 days, and their health was monitored and deaths were recorded. The difference in survival of Δaph1-1-infected larvae (n = 20) and WT-infected larvae (n = 10) was statistically significant (P = 0.028). The P value for Δaph1-2-infected larvae (n = 10) versus WT-infected larvae was 0.062. (B) Mice were inoculated intranasally with C. neoformans WT (n = 10) or Δaph1-1 (n = 20) (5 × 105 yeast cells in 20 µl PBS) and observed daily for signs of ill health. Mice which had lost 20% of their preinfection weight, or which showed debilitating clinical signs, were deemed to have succumbed to the infection and were euthanized. A log rank test stratified by species was then performed using WT and Δaph1-1 data from the larval and mouse study, and this combined analysis demonstrated statistically significant differences between WT and Δaph1-1 (P = 0.012).

To further test the contribution of Aph1 to virulence, mice were inoculated intranasally with Δaph1-1 (n = 20) or WT (n = 10) and monitored for 20 days. We observed an increase in median survival time for the Δaph1-1-infected mice (17 days) compared to the WT (14 days). The resulting P value of the log rank test failed to reach statistical significance (P = 0.16). We therefore combined the larval and mouse studies (strains Δaph1-1 and WT) and performed a log rank test stratified by species. This combined analysis demonstrated statistical significance for the difference in virulence between WT and Δaph1 when both models of cryptococcosis were taken into account (P = 0.012) (Fig. 1B). Taken together, these findings suggest that Aph1 contributes to cryptococcal virulence.

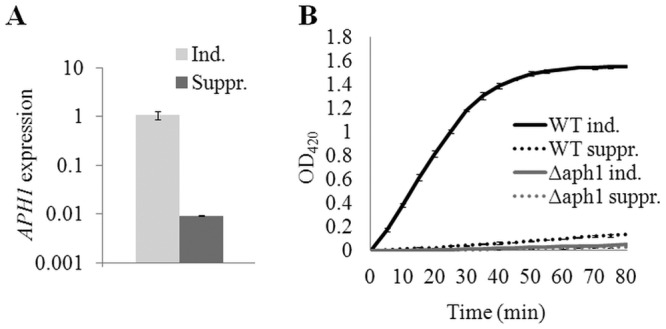

Aph1 production is regulated by phosphate availability.

Next we compared the extent of extracellular acid phosphatase activity in WT and Δaph1. Initially, we established the conditions required for Aph1 production in the WT, based on information obtained from studies of the major secreted acid phosphatase in S. cerevisiae, Pho5. PHO5 gene expression is induced under conditions of limited phosphate availability. Pho5 is exported to the periplasmic space and/or cell wall and excreted into the medium (20, 21). To determine whether cryptococcal Aph1 production is also regulated by phosphate availability, we compared APH1 gene expression (Fig. 2A) and extracellular acid phosphatase activity (Fig. 2B) in WT cells grown in the presence and absence of phosphate. Consistent with the phosphate-repressible expression of PHO5, APH1 expression in WT was upregulated 100-fold in the absence of phosphate (Fig. 2A). Under the same growth conditions, the extracellular acid phosphatase activity of intact WT and Δaph1 cells was measured using the chromogenic acid phosphatase substrate, p-nitrophenyl phosphate (pNPP). The graph in Fig. 2B shows that only WT, induced for 3 h in phosphate-deficient medium, hydrolyzed pNPP at a significant rate over the 80-min time course; Δaph1 exhibited negligible extracellular acid phosphatase activity over this time period in either the presence or absence of phosphate. These results confirm that the majority of extracellular acid phosphatase activity in the WT results from canonically secreted Aph1 and that production of Aph1 is regulated by phosphate availability.

FIG 2 .

Extracellular acid phosphatase Aph1 is induced under phosphate-deficient conditions and is regulated at the transcriptional level. (A) Expression of APH1 was quantified under inducing (Ind.; MM-KCl) and repressing (Suppr.; MM-KH2PO4) conditions by qPCR using ACT1 expression for normalization. (B) WT and Δaph1 were incubated for 3 h under suppressing or inducing conditions. Extracellular acid phosphatase activity of WT and Δaph1 cells was assessed by measuring the hydrolysis of pNPP to pNP at 420 nm, every 5 min, for 80 min. Bars indicate ranges (n = 2).

Identification of physiological substrates of Aph1.

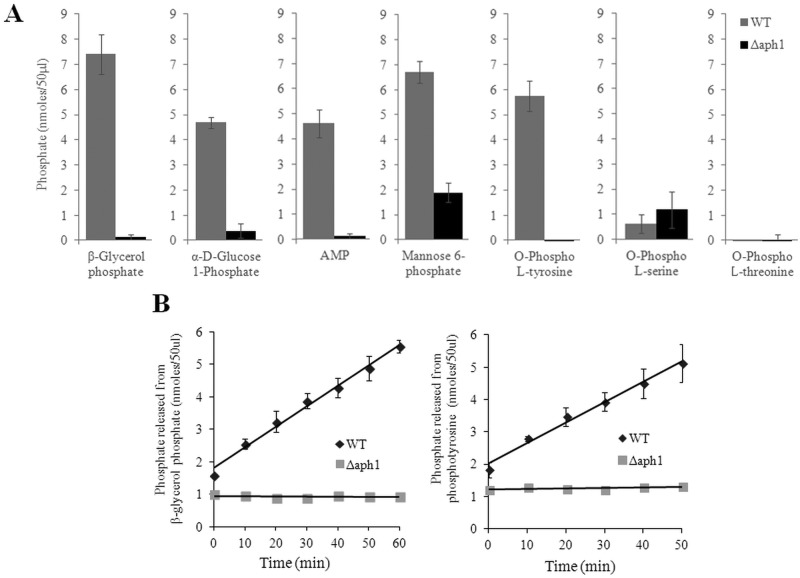

To identify potential physiological substrates of Aph1, we compared the abilities of WT and Δaph1 culture supernatants to hydrolyze several candidate macromolecules following growth of WT and Δaph1 cells under phosphate-deficient conditions. The phosphate released from each substrate as a result of Aph1-mediated hydrolysis was quantified spectrophotometrically using a malachite green assay. Culture supernatant of the WT, but not of Δaph1, hydrolyzed a wide range of macromolecules, including phosphotyrosine, glucose-1-phosphate, β-glycerol phosphate, and AMP (Fig. 3A and B). ATP was also hydrolyzed by WT culture supernatants, but to a lesser extent than AMP (data not shown). No difference was detected between WT and Δaph1 supernatants when phosphothreonine or phosphoserine was used as the substrate (Fig. 3A). Mannose-6-phosphate, which serves as a marker for targeting mammalian proteins to lysosomes, was also hydrolyzed by Aph1 (Fig. 3A).

FIG 3 .

Aph1 catalyzes hydrolysis of β-glycerol phosphate, glucose-1-phosphate, mannose-6-phosphate, phosphotyrosine, and AMP. Phosphate released as a result of hydrolysis of the indicated substrates by WT or Δaph1 culture medium was monitored spectrophotometrically using a malachite green phosphate assay kit. (A) The reaction mixtures were incubated for 40 min, and the released phosphate was quantified. (B) The reaction mixtures were incubated for 60 min, and the phosphate was quantified for every 10-min time point, as indicated.

Visualizing intracellular Aph1.

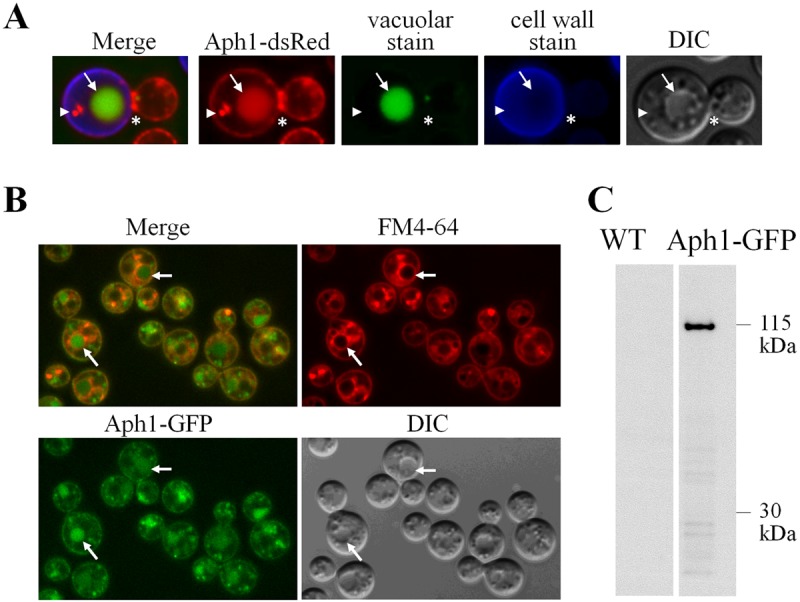

To visualize the subcellular location of Aph1 in C. neoformans, Aph1 was tagged with a red fluorescent protein (DsRed) by replacing the endogenous APH1 gene with an APH1-dsRED gene fusion construct, using homologous recombination (see Fig. S2A and B in the supplemental material). To ascertain that enzymatic activity of Aph1 was not compromised by the addition of DsRed, the extracellular APase activities of Aph1- and Aph1-DsRed-expressing strains were compared in phosphate-free medium (see Fig. S2C). As expected, extracellular APase activity was markedly increased in both strains under inducing conditions. However, the activity of Aph1-DsRed-expressing cells was consistently ~2-fold less than that of WT. This was most likely due to delayed maturation and/or export of the Aph1-DsRed fusion protein.

In cells incubated under inducing conditions (MM-LG) for 3 to 6 h, Aph1-DsRed was visible at the cell periphery and in spherical cytoplasmic structures (Fig. 4A). Some of these Aph1-containing cytoplasmic structures, particularly the larger ones, were identified as vacuoles, since they were costained by carboxy-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (carboxy-DCFDA) (Fig. 4A, arrow). The smaller, non-carboxy-DCFDA-stained structures containing Aph1 were tentatively identified as endosomes (Fig. 4A, arrowhead). Aph1-DsRed was also enriched in emerging bud apices and bud necks (Fig. 4A, asterisk; see also Movie S1 in the supplemental material).

FIG 4 .

Fluorescent-tagged Aph1 is targeted to the cell periphery, vacuoles, and endosome-like structures. (A) Subcellular distribution of Aph1-DsRed in WT cells following a 3-h incubation in phosphate-deficient medium (MM-LG). Aph1-DsRed-expressing cells were stained with carboxy-DCFDA and calcofluor white to visualize vacuoles and cell walls, respectively. Aph1-DsRed in a vacuole and an endosome-like structure are indicated by the arrow and arrowhead, respectively. Enrichment of Aph1-DsRed in the bud neck is marked by the asterisk. DIC, differential interference contrast image. (B) WT cells expressing Aph1-GFP were grown in YNB overnight, washed, incubated in phosphate-deficient medium (MM-LG) for 6 h, and then stained with FM 4-64 for 15 min. Arrows indicate large vacuoles with FM 4-64 incorporated into the membrane and green Aph1-GFP filling the lumen. (C) TRIzol-extracted proteins from Aph1-GFP-expressing and WT cells grown under inducing conditions (MM-LG) were analyzed by Western blotting using anti-GFP antibody. Intact Aph1-GFP (115 kDa) was detected in Aph1-GFP-expressing cells but not in WT (Aph1-expressing) cells.

Since formation of DsRed tetramers can potentially alter the localization of the tagged protein (32), APH1 was also fused with GFP and visualized by fluorescence microscopy. Figure 4B demonstrates that Aph1-GFP had a similar distribution to Aph1-DsRed, confirming that the DsRed tag does not alter Aph1 targeting. Notably, the lipophilic dye FM 4-64, used to visualize the endocytic route from the plasma membrane to vacuoles via endosomes, occasionally colocalized with small endosome-like structures containing Aph1-GFP, supporting our identification of these organelles as endosomes. Localization of Aph1-GFP in vacuoles was confirmed by the observation that FM 4-64 was often observed in the vacuolar membranes surrounding the Aph1-GFP-containing lumen (Fig. 4B, arrows). We used Western blot analysis to further confirm that the localization of Aph1-GFP in vacuoles was due to the specific targeting of Aph1-GFP to this organelle, rather than nonspecific targeting of the cleaved GFP moiety from a potentially unstable fusion protein. After 4 h of induction in phosphate-free medium (MM-LG), cell-associated Aph1-GFP was detected in Aph1-GFP-expressing cells as a single band with a mass of 115 kDa, using anti-GFP antibody (Fig. 4C). As expected, the band was absent in WT. The mass of Aph1-GFP (115 kDa) is larger than the expected 85-kDa size of the fusion protein, as the mass of Aph1 (after SP cleavage) and GFP are 58 and 27 kDa, respectively. Glycosylation most likely accounts for the increase in the observed mass. Similarly, the size of fully glycosylated Pho5 in S. cerevisiae is more than 100 kDa, while unglycosylated protein without SP is predicted to be 51 kDa. The nascent Pho5 protein is core glycosylated at approximately 12 sites, and proper glycosylation is important for folding and secretion of the enzyme (33).

Aph1 is transported to the periphery and vacuoles via endosome-like structures.

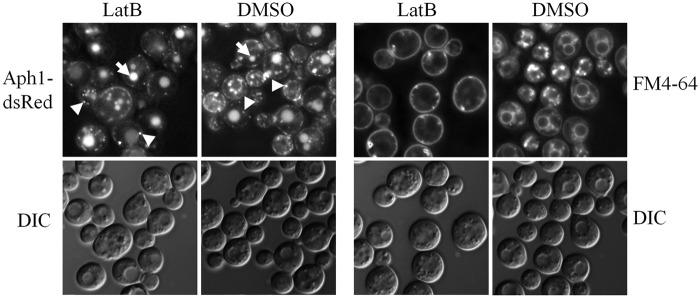

Aph1 is predicted to be transported to the cell periphery from the Golgi apparatus: it contains an SP, and its size indicates that it is glycosylated like its Pho5 homologue in S. cerevisiae. Aph1 could be transported from the Golgi apparatus via three possible routes: (i) exclusively via endosome-like structures, with part of the endosomal pool directed to the vacuole and the other part to the plasma membrane; (ii) partly via endosome-like structures (for delivery to vacuoles) and partly via secretory vesicles (transported directly to the plasma membrane; secretory vesicles are smaller than endosomes and not discernible by fluorescence microscopy); (iii) exclusively via secretory vesicles, which are then recycled from the plasma membrane and delivered to vacuoles via endosome-like structures. To rule out the third possibility, Aph1-DsRed-expressing cells were treated with the actin-depolymerizing agent latrunculin B (LatB) to inhibit endocytosis. After 3 h of incubation with LatB, the cells displayed markedly reduced endocytosis, as evidenced by diminished internalization of the lipophilic dye FM 4-64 (Fig. 5). Despite the inhibition of endocytosis, Aph1-DsRed still accumulated in endosome-like structures and vacuoles, ruling out the possibility that Aph1 is recycled to endosomes from the plasma membrane and suggesting direct transport of Aph1 to endosome-like structures from the Golgi apparatus (Fig. 5).

FIG 5 .

Aph1 is not recycled to endosomes from the plasma membrane. Aph1-DsRed-expressing cells were treated with the actin-depolymerizing agent and inhibitor of endocytosis, LatB, during the 3-h incubation in MM-LG. Abrogated internalization of the lipophilic dye FM 4-64 by LatB-treated cells confirmed that endocytosis was inhibited. Arrows indicate vacuoles and arrowheads indicate endosome-like structures in control (DMSO-treated) and LatB-treated cells. The results confirm the anterograde movement of Aph1 via endosomes. DIC, differential interference contrast images.

We then tracked movement of the Aph1-DsRed-containing organelles by using time-lapse photography. As demonstrated in the movie (see Movie S1 in the supplemental material), Aph1-containing endosome-like structures were often observed to transiently localize at the cell periphery and with vacuoles. This finding suggests that Aph1 is delivered to the plasma membrane and to vacuoles via endosomes and is consistent with the reports of endosome-mediated transport of acid phosphatase to the cell periphery in S. cerevisiae (27, 34). The movie also demonstrates accumulation of Aph1 at the apical regions of emerging buds as well as at the bud necks.

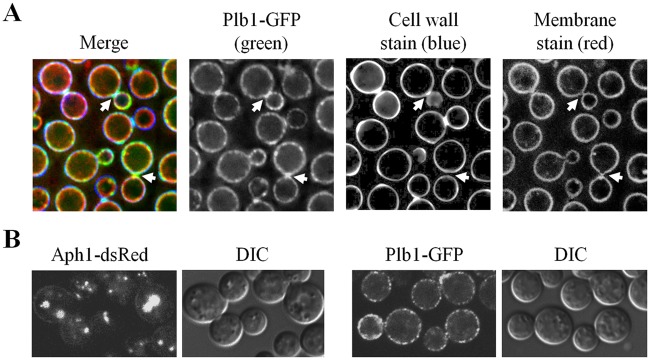

Aph1 and Plb1 secreted via canonical pathways are transported by different routes.

Next, we compared the mode of intracellular transport of Aph1-dsRed with that of Plb1-GFP. Construction and validation of the PLB1-GFP-expressing cryptococcal strain is described in Fig. S3A and B in the supplemental material. In contrast to Aph1, Plb1 is GPI anchored and localizes in membrane and cell wall fractions prior to secretion/excretion (3, 4, 28). Furthermore, GPI-anchored proteins have never been reported to undergo endosome-dependent trafficking to the cell periphery. In contrast to Aph1-DsRed, Plb1-GFP was predominantly localized to the cell periphery and colocalized with both the membrane (FM 4-64)- and cell wall (calcofluor white)-stained areas, consistent with our previous findings. Similar to our findings with Aph1-DsRed, bud necks were enriched in Plb1-GFP (Fig. 6A). Direct comparison of the subcellular localization of Aph1 and Plb1 under the conditions used in our secretome analysis (YNB broth) provided further confirmation of their different intracellular locations (Fig. 6B). The localization of Plb1-GFP at the cell periphery, rather than in intracellular structures, implies that it is transported directly from the Golgi apparatus to the plasma membrane.

FIG 6 .

Aph1 and Plb1 follow endosome-dependent and non-endosome-dependent trafficking routes to the periphery, respectively. (A) WT cells expressing Plb1-GFP were stained with the lipophilic dye FM 4-64 (red) to visualize the plasma membrane and with calcofluor white (blue) to visualize cell walls. Plb1-GFP (green) was present at the cell periphery and was also concentrated in bud necks (arrows). (B) Aph1-DsRed- and Plb1-GFP-expressing cells were grown under the same conditions as those used for the proteomic analysis (YNB broth) to confirm the differences in trafficking routes of these enzymes.

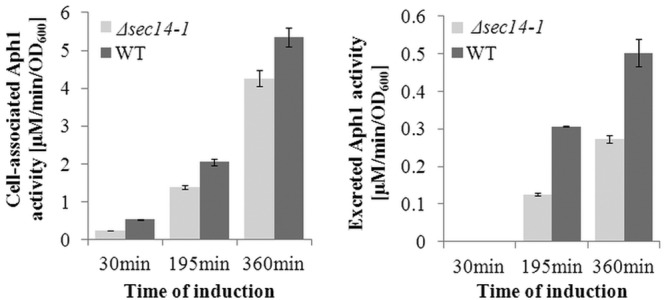

Aph1 secretion is compromised in the Δsec14-1 mutant.

We previously determined that secretion of cryptococcal Plb1 requires the lipid transfer protein Sec14-1 (28). In S. cerevisiae, Sec14 deficiency selectively affects endosome-mediated export of acid phosphatase. To gain insight into the mechanism of Aph1 trafficking, we tested whether Sec14-1 affects secretion of CnAph1. Comparison of the extracellular APase activity (excreted and cell associated) produced by WT and the Sec14-1 deletion mutant Δsec14-1 (Fig. 7) demonstrated that, following the switch to phosphate-free medium, secretion of Aph1 was consistently lower in Δsec14-1 than in the WT.

FIG 7 .

Extracellular Aph1 activity is reduced in the sec14-1 mutant. Extracellular acid phosphatase activity of WT and sec14-1 cells (excreted and cell wall associated) was assayed following a shift to inducing medium (MM-LG). APH activity was measured over 6 h at the indicated time points by monitoring pNPP hydrolysis. Error bars indicate standard deviations of at least three measurements.

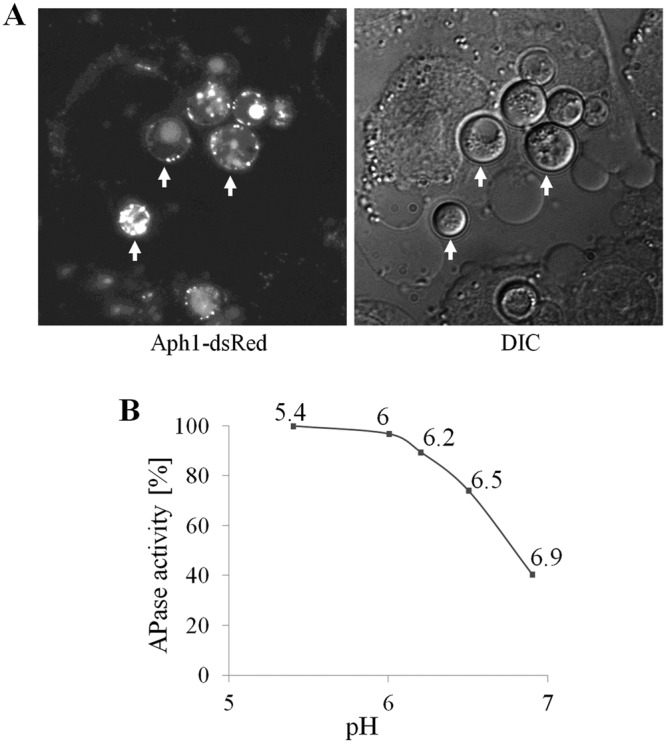

Aph1 is produced during interaction with activated human monocytes and is active at physiological pH.

Since acid phosphatases are implicated in the interactions of microbial pathogens with the mammalian host, we tested whether Aph1 was expressed during the interaction of C. neoformans with the human monocytic cell line THP-1. After 7 h of coculture with gamma interferon (IFN-γ)-activated THP-1 cells, Aph1-DsRed was shown to be expressed in C. neoformans at different stages of phagocytosis, including adhesion to the host cells, invagination of the mammalian cell membrane, and complete enclosure of the pathogen. Subcellular localization of Aph1-DsRed under these conditions (Fig. 8A) was similar to its localization in cryptococci cultured in low-phosphate medium (Fig. 4A). Although Aph1 was expressed in cryptococcal cells during interaction with THP-1 cells, there was no difference in adhesion/uptake of Δaph1 and WT after 4 h of coincubation (data not shown).

FIG 8 .

Aph1 is produced by C. neoformans during coculture with THP-1 monocytes and is active over an acidic pH range. (A) C. neoformans cells harboring the APH1-dsRED gene fusion were cocultured with the human monocytic cell line, THP-1, for 7 h. Red fluorescence due to Aph1-dsRed is visible at the fungal cell periphery and in endosome-like structures and vacuoles (C. neoformans cells are indicated by arrows). (B) Aph1 catalytic activity was quantified spectrophotometrically over the range of pH indicated, by measuring hydrolysis of pNPP.

To test whether Aph1 is catalytically active over the acidic pH range encountered by the pathogen in the mammalian host, we quantified the hydrolysis of pNPP by cryptococcal cells between pH 5.4 and 6.9 (Fig. 8B). The activity of Aph1 dropped as the pH increased and was 60% lower at pH 6.9 compared to that at pH 5.4. These findings suggest that secreted Aph1 is highly active in macrophage phagolysosomes (pH 4 to 5) and that it is likely to retain significant activity in inflamed lung tissue, where the pH is approximately 6.9 (35, 36), and in cryptococcomas, where the extracellular pH is 5.5 due to high acetic acid production (37). Thus, by providing a source of inorganic phosphate, it could potentially contribute to fungal growth in these microenvironments.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we performed a proteomic analysis of the secretome of the C. neoformans serotype A strain H99 and identified canonically secreted Aph1 as the enzyme responsible for extracellular acid phosphatase activity. Aph1 was not detected in previous analyses of cryptocococcal secretomes (29, 30). We suggest that our ability to do so resulted from (i) the incorporation of an SDS-PAGE purification step to remove contaminating soluble capsular material, and (ii) the possibility that the other studies were done using standard growth media, most of which contain phosphate, which represses APH1 expression. To understand the role of Aph1 in cryptococcal cellular function, we characterized its enzymatic activity, mode of regulation, and route of intracellular traffic by using an APH1 deletion mutant and an Aph1-DsRed-expressing strain.

Overview of the WT secretome.

Many of the canonically secreted proteins identified in the WT secretome are predicted to have roles in cell wall biosynthesis and remodeling, iron acquisition, and virulence (see >Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Cda1, Cda2, and Cda3 (CNAG_05799, CNAG_01230, and CNAG_01239) are chitin deacetylases involved in the conversion of chitin to chitosan, which is essential for cell wall integrity, bud separation, and melanin retention (38). Ags1 is the major α-1,3-glucan biosynthesis enzyme in C. neoformans and is essential for cell wall integrity and retention of capsular material to the cell wall (39). Kre61 is one of seven genes in the KRE family and is putatively involved in the synthesis of β-1,6-glucan (40). The combined deletion of KRE61 and another family member, SKN1, is thought to be lethal in C. neoformans (41). Gas1 (CNAG_06501), the homologue of Gas1 from S. cerevisiae, is a β-1,3-glucanosyltransferase thought to elongate and rearrange the side chains of the 1,3-β-glucan polymers (42). GAS1 deletion results in enlarged cells, weakened cell walls, and a cell separation defect (43, 44). Three GPI-anchored H2O2-producing glyoxal oxidases (CNAG_05731, CNAG_00407, and CNAG_02030) were also identified in the H99 secretome. In the phytopathogenic basidiomycete Ustilago maydis, the membrane-bound glyoxal oxidase Glo1 is required for filamentous growth and pathogenesis, and a cell wall defect in Δglo1 indicates a potential role for Glo1 in cell wall maturation (45). The secreted mannoprotein Cig1 (CNAG_01653) mediates iron uptake via the binding and transport of heme (46, 47). Finally, the two well-characterized virulence determinants laccase 1 and Plb1 were also identified. Laccase (CNAG_03465) is targeted to the cell wall via a unique C-terminal sequence (5), while Plb1 associates with the cell membrane and cell wall via a GPI anchor.

A large proportion of the WT secretome (74%) consists of proteins that are not trafficked via the canonical ER/Golgi apparatus route. In agreement with our findings, 87.5% and 35% of the proteins identified in the secretomes of pathogenic Paracoccidioides species (25) and Candida albicans (24), respectively, were secreted via noncanonical pathways. One mechanism of secretion via noncanonical pathways involves multivesicular bodies (MVBs), which contain vesicles enclosing cytoplasmic contents. These vesicles are derived from an invaginated MVB membrane and can be released into the extracellular milieu as exosomes following the fusion of MVBs with the plasma membrane. Rodrigues et al. (23) observed extracellular exosome-like vesicles in the secretions and cell walls of C. neoformans, and they identified 76 proteins, mainly of cytosolic origin, associated with them. Sixteen out of 76 proteins identified in these exosomes were ribosomal proteins. These, and other, cytosolic proteins are thought to be present in exosomes due to the random sampling of cytosolic content during invagination of the MVB to form exosomes (48). Many proteins identified in our study, including ribosomal proteins, were previously found in association with fungal exosomes (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) (23, 49). This finding suggests that the trichloroacetic acid (TCA) precipitation step used in our method caused the precipitation of both soluble proteins and exosomes. In support of this, TCA has been used to precipitate extracellular vesicles in a number of other studies (50, 51).

Interestingly, Aph1 was also detected in association with exosomes, despite the presence of the signal peptide (23). It is possible that APase activity detected in association with exosomes was due to the binding of soluble enzyme to the external surface of exosomes, since pNPP substrate is not membrane permeable. The Aph1 detected in the H99 secretome in our study most likely represents soluble enzyme, since the short Aph1 induction time required for quantification of APase activity would be insufficient for substantial exosome production (Fig. 7; see also Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

Phosphate-repressible Aph1 is the major secreted acid phosphatase in C. neoformans.

Extracellular acid phosphatase activity has been detected in multiple fungal species, including C. neoformans (8, 17, 52). Extracellular APases provide fungal cells with a source of inorganic phosphate, as evidenced by phosphate-dependent expression of these enzymes (11, 16–18). Coordinated regulation of genes involved in inorganic phosphate uptake, including permeases and acid and alkaline phosphatases, was extensively studied in the nonpathogenic yeast S. cerevisiae (for review, see reference 20). By creating the Δaph1 mutant, we confirmed that Aph1 is the main acid phosphatase secreted by C. neoformans, and we demonstrated the absence of extracellular acid phosphatase activity in this mutant. Expression of APH1 was suppressed in the presence of phosphate and induced when phosphate was depleted, similar to Pho5 in S. cerevisiae (21). This observation suggests that Aph1 plays a role in scavenging phosphate when the pool of intracellular phosphate is diminished.

Aph1 also accumulates in cryptococcal vacuoles and bud necks.

As with acid phosphatases produced by S. cerevisiae and Colletotrichum graminicola (53, 54), Aph1 is transported to vacuoles. In plants, phosphate starvation triggers de novo biosynthesis of secreted and intracellular acid phosphatases (55). One of the Arabidopsis thaliana acid phosphatases, AtPAP26, which, like CnAph1, is both secreted and targeted to the vacuoles, recycles phosphate from nonessential phosphate monoesters (56). The likely activity of CnAph1 in vacuoles is supported by our findings that Aph1 has an acidic pH optimum (Fig. 8B) and that phosphotyrosine is one of its substrates. Phosphotyrosine is likely to be present on proteins targeted to vacuoles for turnover.

The enrichment of Aph1 at buds and bud necks suggests that Aph1 plays a role in bud formation and/or septation (Fig. 4). However, this function seems to be redundant, since we did not observe any obvious growth defects in Δaph1 on standard yeast medium or even in the presence of β-glycerol phosphate as a sole phosphate source (unpublished observation). Acid phosphatase activity has been detected in glucanase-containing vesicles targeted to the buds and bud necks in S. cerevisiae (53). Bud necks are the most actively growing areas of the cell wall, and it is possible that acid phosphatase activity affects cell wall growth and structural properties, for example, via dephosphorylation-mediated activation of enzymes involved in cell wall biosynthesis or dephosphorylation of cell wall building blocks (57, 58).

While Aph1 was identified extra- and intracellularly, Plb1 was predominantly localized at the cell periphery. Peripheral localization of Plb1 is consistent with our previous work, where we demonstrated its association with membrane and cell wall fractions via a GPI anchor (2–4). Interestingly, Plb1 was also enriched in bud necks, suggesting that it also has a role in bud formation and/or release. In support of this, the PLB1 deletion mutant has a cell wall integrity defect (3) and grows more slowly than WT in some media (unpublished observation), but not in yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YPD) medium (1).

Transport of Aph1 is mediated by endosomes and requires functional Sec14-1.

In phosphate-deficient medium, DsRed-tagged Aph1 accumulated rapidly in subcellular compartments that did not stain with the vacuolar marker DCFDA (Fig. 4). We tentatively identified these organelles as endosomes. To support this identification, Aph1-DsRed-enriched structures occasionally costained with the endocytic system marker FM 4-64, which has been used to visualize endosomes (Fig. 4) (59). Transport of acid phosphatase via endosomes has been documented for S. cerevisiae (27). In rat hepatocytes, newly synthesized acid phosphatase is transported to lysosomes via endosomes (60). Time-lapse microscopy (see Movie S1 in the supplemental material) and our endocytosis inhibition experiment (Fig. 5) suggested that cryptococcal endosome-like structures mediate transport of newly synthesized Aph1 to both the cell surface and to vacuoles.

Similar to the secretion of Plb1, which is transported directly to the plasma membrane, we also observed that secretion of Aph1 is reduced in the absence of the CnSEC14-1 gene. In S. cerevisiae, Sec14 is a phosphatidylinositol/phosphatidylcholine transfer protein that regulates both endosome-dependent (invertase and acid phosphatase) and endosome-independent (cell wall enzyme Bgl2) protein traffic (27), implying that similar secretion regulatory mechanisms operate in S. cerevisiae and C. neoformans.

Contribution of Aph1 to pathogenicity.

Using two well-accepted models of cryptococcosis, we demonstrated that Aph1 contributes to pathogenicity (Fig. 1). We also demonstrated that Aph1 is produced by cryptococci during contact with, and uptake by, human monocytes, suggesting that Aph1 is active in the host environment (Fig. 8A). The modest impact of Aph1 on cryptococcal pathogenicity in experimental animals may be the result of compensation for Aph1 deficiency by one or more of the other three acid phosphates, particularly the closest Aph1 homologue, CNAG_06967. Since these acid phosphatases are not predicted to be secreted, we conclude that the absence of extracellular APase activity does not significantly affect cryptococcal virulence. It is possible that intracellular APase activity is more important for fungal homeostasis and virulence, with phosphate recycling in cryptococcal vacuoles contributing more significantly to intracellular phosphate homeostasis than phosphate scavenged from the extracellular milieu, including host phagolysosomes.

Surface and/or secreted phosphatase activity contributes to adhesion of fungal pathogens, including Candida parapsilosis (9, 61), Fonsecaea pedrosoi (18, 62), Rhinocladiella aquaspersa (17), and C. neoformans (52) to host tissue. Interestingly, we did not observe any differences in the adherence of WT and Δaph1 to the human monocytic cell line THP-1. A possible reason is that the adhesion assay was performed under pH conditions (pH ~7.4) which are not conducive to optimal catalytic activity of Aph1. The adhesion and activity assays performed by Collopy-Junior et al. (52), who used a range of phosphatase inhibitors, were performed at pH 7.4 and pH 7, respectively, suggesting that some of the activity detected in this study may be attributable to alkaline phosphatases. Extracellular Aph1 produced in vivo is unlikely to play a role in adhesion. However, it may promote the interaction of cryptococci with host cells, particularly in the fluid constituting the lung lining, which is more acidic than blood, especially during inflammation (36), and in cryptococcomas (pH 5.5) (35, 37, 63). Secreted Aph1 may facilitate the recycling of free phosphate from these acidic microenvironments, including phagolysosomes. However, as mentioned above, our results suggest that the recycling of phosphate in the cryptococcal vacuole by intracellular acid phosphatases is more likely to contribute to fungal homeostasis and virulence.

In summary, we have identified Aph1 as a component of the secretome of C. neoformans and as a major phosphate-repressible acid phosphatase with a broad substrate specificity. We also established that Aph1 is transported to the cryptococcal cell periphery and vacuoles via endosome-like structures and that its transport is compromised in the absence of Sec14-1. Our findings suggest that the main function of Aph1 in cryptococci is within vacuoles rather than in secretions, where it recycles phosphate from a variety of macromolecules. We also demonstrated that Aph1 is expressed under physiological conditions and contributes to cryptococcal pathogenicity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungal strains and growth media.

Wild-type C. neoformans var. grubii strain H99 (serotype A, MATa) and the SEC14-1 deletion mutant (28) were used in this study. Routinely, the cells were grown in YNB (6.7 g/liter yeast nitrogen base, 0.5 to 2% glucose) or YPD (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, and 2% dextrose), as indicated. Phosphate-deficient minimal medium with low glucose (MM-LG; 0.1% glucose, 10 mM MgSO4, 0.5% KCl, 13 mM glycine, 3 µM thiamine, 10 µM CuSO4) or MM-KCl medium (0.5% KCl, 15 mM glucose, 10 mM MgSO4⋅7H2O, 13 mM glycine, 3.0 µM thiamine) were used to induce acid phosphatase activity. MM-KH2PO4 (0.5% KH2PO4, 15 mM glucose, 10 mM MgSO4⋅7H2O, 13 mM glycine, 3.0 µM thiamine) was used as a control medium in which APase activity was suppressed. Plasmids pJAF and pCH233 were a gift from John Perfect (Duke University, NC).

Purification and identification of secreted proteins.

Cells were grown overnight in 10 ml YNB broth supplemented with 2% glucose at 30°C. The cultures were diluted to 40 ml with fresh YNB and grown for another 18 to 20 h. The medium was concentrated 80-fold by using an Amicon Ultra concentrator (30-kDa cutoff). Due to the high viscosity of the concentrate, the samples were diluted to 7 ml with imidazole buffer (125 mM imidazole, pH 4). A volume containing 100 µg of protein was precipitated with TCA (10%, final concentration), washed with ice-cold acetone, dried, dissolved in lithium dodecyl sulfate loading buffer (Life Technologies), and loaded onto an SDS-polyacrylamide gel. The gel was stained with Sypro Ruby protein stain (Invitrogen). Each lane was cut into four pieces, and the proteins within each piece were trypsinized and analyzed by mass spectrometry. The experiment included two biological replicates. Thus, a total of 8 gel slices were analyzed in technical duplicate by mass spectrometry. Briefly, the gel slices were diced, destained 2 to 4 times for 10 min each in 60% (vol/vol) 20 mM ammonium bicarbonate, 40% (vol/vol) acetonitrile, then rinsed twice in acetonitrile, dried with a vacuum centrifuge, and rehydrated in approximately 100 µl of 12-ng/µl sequencing-grade porcine trypsin (Promega, Sydney, Australia) for 1 h at 4°C. Excess trypsin was removed, a sufficient volume of 20 mM ammonium bicarbonate buffer was added to cover the gel pieces, and samples were incubated at 37°C overnight. Peptides were concentrated and desalted using C18 microcolumns (Millipore, Billerica, MA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, eluted in 5 µl of 70% (vol/vol) acetonitrile and 0.1% (vol/vol) formic acid into a low-bind 96-well plate (Eppendorf, Düsseldorf, Germany), and then diluted with 45 µl of 0.1% (vol/vol) formic acid. Peptides were desalted on a Zorbax 300SB-C18 trap (5 µm, 5 by 0.3 mm; Agilent Technologies) and separated using an in-house-prepared fritted nanocolumn packed with Reprosil-Pur C18 (3 µm, 75 µm by 150 mm; Dr. Maisch GmbH, Ammerbuch, Germany) on an Agilent 1100 high-performance liquid chromatography system coupled to an AB Sciex QSTAR Elite quadrupole time-of-flight MS system for analysis. Peptides were eluted using a gradient of 5 to 40% buffer B mixed with buffer A (buffer A, 0.1% [vol/vol] formic acid; buffer B, 0.1% [vol/vol] formic acid in acetonitrile) at a flow rate of 0.3 µl/min. MS survey scans were performed over a range of m/z 350 to 1,750 followed by 3 data-dependent MS/MS scans over a range of m/z 65 to 2,000. Peak lists were generated using Analsyst QS version 2.0 (AB Sciex) and analyzed using MASCOT version 2.2 (Matrix Science, London, United Kingdom) against an in-house Cryptococcus neoformans-specific database (version 20-04-2009; 6,980 sequences). One missed cleavage per peptide, a mass tolerance of 0.2 Da (MS and MS/MS), and variable modification by oxidation of methionine were allowed in the MASCOT search. The MASCOT results were further analyzed in Scaffold version 4.0.5 (Proteome Software Inc., Portland, OR). Peptide identifications were accepted if they could be established at greater than 80% probability. Protein identifications were accepted if they could be established at greater than 90% probability and contained at least 1 identified peptide.

Construction of APH1 knockout and fluorescent strains. (i) APH1 knockout.

The APH1 gene (CNAG_02944 in the C. neoformans H99 serotype A genome database; http://www.broadinstitute.org/annotation/genome/cryptococcus_neoformans/MultiHome.html) deletion construct was created by fusing genomic sequence upstream of APH1 (5′ flank; 787 bp), the neomycin resistance (Neor) cassette (amplified from pJAF vector), and genomic sequence downstream of APH1 (3′ flank; 952 bp) by overlap PCR. The resulting product was cloned into the pJet1.2 vector by using the CloneJet PCR cloning kit (Thermo Scientific). Following biolistic transformation of the H99 strain (64), neomycin-resistant transformants were screened for their ability to secrete acid phosphatase as described below. Transformants exhibiting reduced acid phosphatase activity were further verified by PCR, by amplifying regions across the homologous recombination junctions (data not shown). Primers used to create the APH1 deletion construct and to verify the resulting mutants are listed in Table S2 in the supplemental material.

(ii) APH1-DsRED.

First, we fused DsRED-Express (Clontech) with the EF1T terminator and the Neor cassette by using overlap PCR. The resulting fragment was cloned into the pCR2.1 cloning vector (Life Technologies). Second, the genomic fragment immediately downstream of the APH1 coding sequence (the 3′ flank) was ligated into the AscI and PspOMI restriction sites that follow the Neor cassette. Third, the 3′ end of the C. neoformans APH1 genomic sequence, minus the stop codon (positions 1035 to 1977), was ligated into the KpnI and PacI sites of the vector, joining it in frame with the dsRED sequence, as indicated in Fig. S2A in the supplemental material. Following biolistic transformation of the H99 WT strain, Neor colonies in which native APH1 had been replaced by the recombinant APH1-DsRED-Neor construct were screened for the presence of red fluorescence. Transformants were confirmed by PCR amplification across the APH1-DsRED-Neor recombination junctions (see Fig. S2B).

(iii) APH1-GFP.

An APH1-GFP construct was created by exchanging the DsRED-EF1T-Neor fragment of the APH1-DsRED-EF1T-Neor-pCR2.1 vector with the GFP-EF1T-Natr fragment via the PacI and AscI restriction sites. APH1-GFP-expressing transformants were generated and verified in a manner similar to that used to verify the APH1-dsRED-expressing strain (see Fig. S2A and B in the supplemental material).

(iv) PLB1-GFP.

A PLB1-GFP fusion construct was created by overlap PCR and comprised the following fragments: the 3′ end of the PLB1 genomic sequence (CNAG_06085) minus the GPI anchor motif; the GFP coding sequence; the PLB1 GPI anchor motif; the elongation factor terminator; the Neor cassette and genomic sequence downstream of PLB1 (3′ flank). The GFP was placed in front of the GPI anchor consensus motif (see Fig. S3A in the supplemental material). The position of the motif was determined by using the BIG-PI fungal predictor (http://mendel.imp.ac.at/sat/gpi/fungi_server.html). The Neor cassette was PCR amplified from pJAF, and the EF1T and GFP sequences were amplified via pKUTAP-2. The final construct was introduced into WT strain H99 by using biolistic transformation. Transformants in which the PLB1-GFP fusion construct had replaced the endogenous PLB1 gene by homologous recombination were selected on YPD agar supplemented with 200 µg/ml G418 and screened for the presence of green fluorescence. Targeted integration of the PLB1-GFP-Neor construct at the PLB1 locus was confirmed based on the ability to PCR amplify across the PLB1-GFP-Neor recombination junctions, as described in the Fig. S3 legend in the supplemental material.

APH1 expression.

WT cells were grown overnight in YPD, washed, and incubated for 3 h in inducing (MM-KCl) or suppressing (MM-KH2PO4) medium and then snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. The cells were homogenized by bead beating in the presence of glass beads and TRIzol (Ambion), and RNA was extracted following the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was synthesized using Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Promega). APH1 transcript was quantified by quantitative PCR (qPCR) using the SYBR green real-time PCR master mix (Life Technologies) on a Rotorgene 6000 qPCR machine (Corbett Research). APH1 expression was normalized against the expression of actin (ACT1) as a housekeeping gene before final quantification using the 2−ΔΔCT calculation method.

Measuring kinetics of p-nitrophenyl phosphate hydrolysis by extracellular acid phosphatase.

WT and Δaph1 were grown overnight in YPD. The cells were washed with water and resuspended in MM-KH2PO4 or MM-KCl medium at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1. The cultures were incubated at 30°C for 3 h. Following incubation, 17 50-µl aliquots of each culture were removed and assayed for acid phosphatase activity (Fig. 2B). Each reaction mixture contained 50 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.2) and 2.5 mM p-nitrophenyl phosphate in a final volume of 400 µl. Reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C and stopped at different time points (5 to 80 min) by adding 800 µl of saturated Na2CO3. The extent of p-nitrophenyl phosphate hydrolysis was measured spectrophotometrically at 420 nm. The assay was performed in duplicate.

Aph1 induction time course.

C. neoformans strains were grown overnight in YNB broth supplemented with 0.5% glucose at 30°C. For the Aph1 induction time course analysis (Fig. 7; see also Fig. S2C in the supplemental material), the cells were pelleted by centrifugation, washed with water, resuspended to an OD600 of 1 in MM-LG, and incubated to induce APase activity for up to 10 h. To measure cell-associated APase activity at each time point, the aliquot of cells was centrifuged and the pellet was resuspended in 400 µl of reaction mixture (50 mM sodium acetate buffer [pH 5.2], 2.5 mM pNPP). To measure APase activity released into the culture medium at each time point, 500 µl of the culture was centrifuged to pellet the cells, and 383.3 µl of the supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube. The volume was adjusted to 400 µl by adding 6.7 µl of 3 M sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.2; 50 mM final concentration) and 10 µl of 100 mM pNPP substrate (2.5 mM, final concentration). Following incubation at 37°C, the reactions were stopped by adding 800 µl of saturated Na2CO3. APase-mediated hydrolysis of pNPP was quantified spectrophotometrically at 420 nm. Acid phosphatase specific activity was expressed as the concentration (µM) of pNPP hydrolyzed to pNP by cells from 100 µl culture per minute per fungal culture OD600. The concentration of pNP was calculated using the molar extinction coefficient of pNP (ε = 18 mM−1 cm−1).

Galleria mellonella infection model.

C. neoformans WT and Δaph1 cells were grown overnight, pelleted by centrifugation, and resuspended in water at a concentration of 108 cells/ml. G. mellonella larvae (10 to 20 per strain) were inoculated with 10 µl of cell suspension (106 yeast cells) by injection into the hemocoel via the lower pro-legs. The viability of each inoculum was assessed by performing serial 10-fold dilutions, plating the dilutions onto Sabouraud’s (SAB) agar plates, and counting the CFU after a 3-day incubation at 30°C. Inoculated larvae were monitored daily for 13 days. The Kaplan-Meier method in the SPSS statistical software (version 20) was used to estimate the differences in survival (log rank test) and to plot the survival curves. In all cases, a P value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Murine inhalation model of cryptococcosis.

All procedures described are approved and governed by the Sydney West Local Health District Animal Ethics Committee, Department of Animal Care. Survival analysis was conducted using 7-week-old female BALB/c mice obtained from the Animal Resource Centre, Floreat Park, Western Australia, Australia. For both sets of analyses, mice were anesthetized using isoflurane (in oxygen) delivered via an isoflurane vaporizer attached to a Stinger small animal anesthetic machine (Advances in Anaesthesia Specialists). Groups of 10 to 20 mice were then inoculated intranasally with C. neoformans WT or the Δaph1 mutant strain (5 × 105 yeast cells in 20 µl phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]) and observed daily for signs of ill health. Numbers of viable yeast cells inoculated into the nares were later confirmed by quantitative culture. Mice which had lost 20% of their preinfection weight, or which showed debilitating clinical signs prior to losing this weight, including hunching, respiratory distress, excessive fur ruffling, or sluggish/unsteady movement, were deemed to have succumbed to the infection and were euthanized by CO2 inhalation followed by cervical dislocation. Differences in survival were determined with SPSS version 21 statistical software, using the Kaplan-Meier method (log rank test), where a P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Identification of Aph1 substrates.

MM-KCl broth (Aph1-inducing medium) was inoculated with WT and Δaph1 cells at an OD600 of 1 and incubated overnight. After pelleting the cells, the supernatant was used as a source of active enzyme. Each reaction mixture (50 µl) contained 25 µl culture supernatant, 100 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.2), and 5 mM substrate (O-phospho-l-tyrosine, β-glycerol phosphate disodium salt pentahydrate, O-phospho-l-serine, O-phospho-l-threonine, mannose-6-phosphate, and AMP [Sigma]). The reactions were initiated by addition of the substrate and incubated at 37°C with gentle shaking for 40 min or, for the time course analysis, between 0 and 60 min. The released phosphate in 10 µl of each reaction mixture was then quantified by spectrophotometry by using a malachite green phosphate assay kit (Cayman Chemical). For each substrate tested, a reaction without enzyme was included as a control to measure the amount of free phosphate present in the substrate solution prior to the addition of enzyme. This value was then used to calculate acid phosphatase-mediated phosphate release.

Aph1 activity at different pHs.

MM-KCl broth (Aph1-inducing medium) was inoculated with WT and Δaph1 cells at an OD600 of 1 and incubated overnight. Each reaction mixture (400 µl) contained 20 µl culture (cells and medium), 50 mM MES (pH 5.4 to 6.9), as indicated, and 2.5 mM pNPP. The reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 7 min and stopped by addition of 600 µl of saturated Na2CO3. Aph1-mediated hydrolysis of pNPP was quantified spectrophotometrically at 420 nm.

Western blot assays.

C. neoformans Aph1-GFP-expressing cells were grown overnight in YNB broth supplemented with 0.5% glucose at 30°C. The cells were pelleted by centrifugation, washed with water, resuspended to an OD600 of 1 in MM-LG, and incubated for 4 h to induce APH activity. The cells were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, homogenized by bead beating in TRIzol (Ambion) in the presence of glass beads, and further processed to extract total protein, following the manufacturer’s instructions. Aph1-GFP was detected by Western blotting with anti-GFP IgG (sc9996; 1:80 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) followed by anti-mouse IgG–horseradish peroxidase conjugate (NA9310V; 1:1,000 dilution; Amersham). Signals were detected by chemiluminescence, following exposure to X-ray film.

Microscopy.

All fluorescence was viewed using a DeltaVision deconvolution microscope. To visualize Aph1-DsRed and Aph1-GFP, the cultures were grown overnight in YNB, washed with water, resuspended in MM-LG at an OD600 of 1, and incubated for at least 3 h (Fig. 4). To stain fungal vacuoles, the cells were incubated with 3 µM carboxy-DCFDA for 15 min in MM-LG. The cell walls were stained with 0.5 µg/ml calcofluor white (5-min incubation) (Fig. 4A). To visualize the endocytic system (Fig. 4B), the cells were stained with 2 µg/ml FM 4-64 for 15 min at room temperature to allow the dye to reach vacuoles.

To visualize Plb1-GFP (Fig. 6A), the cultures were grown overnight in YPD broth at 30°C. To stain cell walls and plasma membranes, the cells were pelleted, resuspended in PBS, and incubated for 5 min with 0.5 µg/ml calcofluor white or 2 µg/ml FM 4-64, respectively. To prevent internalization of FM 4-64, the cells were stored on ice until the time of viewing. For comparative visualization of Aph1-dsRed and Plb1-GFP (Fig. 6B), the cultures were grown in YNB broth at 30°C.

To determine whether Aph1 was recycled from the plasma membrane by endocytosis (Fig. 5), YNB-grown Aph1-dsRed-expressing cells were washed, resuspended in MM-LG at an OD600 of 1 in the presence of 150 µM LatB or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; solvent control), and incubated for 3 h. To confirm that LatB was inhibiting endocytosis in a control experiment, 1 µg/ml FM 4-64 was added to WT cultures for the last 30 min of the 3-h incubation with either LatB or DMSO.

Interaction of C. neoformans with monocytes.

The human monocytic cell line THP-1 was maintained in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and activated by the addition of 10 ng/ml IFN-γ 24 h prior to coculture with C. neoformans. C. neoformans Aph1-DsRed-expressing cells were propagated overnight in YNB broth (0.5% glucose), conditions under which weak basal Aph1-DsRed expression was detected, and opsonized with 50% human serum (diluted with water) for 30 min. Opsonized fungal cells were pelleted by centrifugation and combined with activated THP-1 cells (106 C. neoformans cells per 106 THP-1 cells, in 200 µl RPMI-FBS medium). The coculture was incubated at 37°C–5% CO2 for 7 h prior to examination by fluorescence microscopy.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Functional classification of the 105 proteins identified in WT secretions. Proteins in each functional category were further divided into three groups: signal peptide-containing proteins (SP+, black), SP− proteins previously found in C. neoformans and/or S. cerevisiae extracellular vesicles (diagonal pattern), and the remaining proteins secreted via noncanonical pathways (gray). The presence of SP was predicted by using the SignalP online prediction tools (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/). Association of the proteins with extracellular vesicles (EVs) was established based on findings reported previously (23, 50). Although several of the SP+ proteins identified have reported associations with EVs, they were excluded from the EV category in this analysis. Download

Construction of the APH1-dsRED-expressing strain and verification of Aph1-DsRed enzymatic activity. (A) The APH1-DsRED-Neor construct was created as described in Materials and Methods and comprised the 3′ end of the APH1 genomic sequence (positions 1045 to 1991); dsRED (Clontech); the elongation factor terminator (EF1T); a neomycin resistance cassette (actin promoter, P_actin), aminoglycoside phosphotransferase gene (Neor), tryptophan terminator (T_Trp), and genomic sequence downstream of APH1 (3′ flank). The APH1-GFP vector was similarly constructed using GFP-EF1T and the nourseothricin resistance cassette (Natr). The restriction sites used to construct APH1-DsRED and the primers used to screen for replacement of APH1 with APH1-dsRED/APH1-GFP are indicated. (B) The APH1-DsRED-Neor construct was introduced into C. neoformans H99 WT by biolistic transformation, and neomycin-resistant transformants were screened for the replacement of the native APH1 by APH1-dsRED using PCR. The APH1-5′ots-s PCR primer was designed to anneal to APH1 sequence upstream of the integration site, while the Red-a-PacI primer was specific for the dsRED sequence. Thus, the PCR across the recombination junction yielded a 1.7-kb product. Similarly, Ttrp-s and APH1-3′ots-a primers were designed to amplify a DNA fragment across the recombination junction of the APH1-DsRED-Neor 3′ flank and the APH1 genomic sequence, generating a 1-kb product. No specific PCR products were observed when WT genomic DNA was used as a template. The APH1-GFP-Natr construct was introduced into WT H99 cells. Primer pairs APH1-5′ots-s–ActP-s and Ttrp-s–APH1-3′ots-a were used to establish targeted integration of APH1-GFP-Natr, generating 3-kb and 1-kb PCR products, respectively. (C) Quantification of the cell-associated acid phosphatase activity in Aph1-DsRed-expressing strain, compared to WT. The cells were grown in YNB, washed, and resuspended in acid phosphatase-inducing medium (MM-LG). The cell-associated APH activity was assayed at the indicated time points by using the chromogenic substrate p-nitrophenyl phosphate, as described in Materials and Methods. Download

Construction of the PLB1-GFP-expressing strain. (A) The PLB1-GFP-Neor construct was created by overlap PCR as described in Materials and Methods and comprised the PLB1 genomic sequence (positions 82 to 2135); GFP; the PLB1 GPI anchor motif (positions 2136 to 2222); the EF1T; a Neor cassette (actin promoter [P_actin], Neor gene, and tryptophan terminator [T_Trp]), and genomic sequence downstream of PLB1 (3′ F). (B) The PLB1-GFP-Neor construct was introduced into C. neoformans H99 WT by biolistic transformation, and neomycin-resistant transformants were screened for the replacement of endogenous PLB1 by PLB1-GFP via PCR. The 5′ PCR primer (PLB1-ots-s) was designed to anneal to PLB1 sequence upstream of the integration site, while the 3′ primer was specific for the GFP sequence (GFP-a). Thus, PCR amplification across the recombination junction yielded a 1.6-kb product in PLB1-GFP-expressing transformants. No PCR product was observed when ectopic integration of the construct occurred. Download

Functional classification of the proteins identified in WT secretions via mass spectrometry. Normalized spectral counts for each protein (average of 4 replicates) are indicated. Association of the proteins with C. neoformans and S. cerevisiae exosomes was established based on publications by Rodrigues et al. (23) and Oliveira et al. (49). Positive or negative predictions of signal peptides (SP) and GPI anchors are indicated.

Primers used in this study. Uppercase nucleotides in the oligonucleotide sequences are complementary to the template, while lowercase nucleotides indicate added adaptor sequences.

Dynamics of movement of Aph1-DsRed-containing organelles in WT cells. The cells were grown in YNB, washed, and incubated in inducing medium (MM-LG) for 3 h. Download

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Hong Yu for assistance with fluorescence microscopy, Shuyao Duan and Aziza Khan for preparation of the G. mellonella larvae, and Karen Byth for assistance with statistical analysis.

This work was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia grant (632634). T.C.S. is a Sydney Medical School Foundation Fellow. This work was funded, in part, by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NIAID.

Footnotes

Citation Lev S, Crossett B, Cha SY, Desmarini D, Li C, Chayakulkeeree M, Wilson CF, Williamson RR, Sorrell TC, Djordjevic JT. 2014. Identification of Aph1, a phosphate-regulated, secreted, and vacuolar acid phosphatase in Cryptococcus neoformans. mBio 5(5):e01649-14. doi:10.1128/mBio.01649-14.

REFERENCES

- 1. Cox GM, McDade HC, Chen SC, Tucker SC, Gottfredsson M, Wright LC, Sorrell TC, Leidich SD, Casadevall A, Ghannoum MA, Perfect JR. 2001. Extracellular phospholipase activity is a virulence factor for Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol. Microbiol. 39:166–175. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02236.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Djordjevic JT, Del Poeta M, Sorrell TC, Turner KM, Wright LC. 2005. Secretion of cryptococcal phospholipase B1 (PLB1) is regulated by a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor. Biochem. J. 389:803–812. 10.1042/BJ20050063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Siafakas AR, Sorrell TC, Wright LC, Wilson C, Larsen M, Boadle R, Williamson PR, Djordjevic JT. 2007. Cell wall-linked cryptococcal phospholipase B1 is a source of secreted enzyme and a determinant of cell wall integrity. J. Biol. Chem. 282:37508–37514. 10.1074/jbc.M707913200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Siafakas AR, Wright LC, Sorrell TC, Djordjevic JT. 2006. Lipid rafts in Cryptococcus neoformans concentrate the virulence determinants phospholipase B1 and Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase. Eukaryot. Cell 5:488–498. 10.1128/EC.5.3.488-498.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Waterman SR, Hacham M, Panepinto J, Hu G, Shin S, Williamson PR. 2007. Cell wall targeting of laccase of Cryptococcus neoformans during infection of mice. Infect. Immun. 75:714–722. 10.1128/IAI.01351-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhu X, Gibbons J, Garcia-Rivera J, Casadevall A, Williamson PR. 2001. Laccase of Cryptococcus neoformans is a cell wall-associated virulence factor. Infect. Immun. 69:5589–5596. 10.1128/IAI.69.9.5589-5596.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vidotto V, Ito-Kuwa S, Nakamura K, Aoki S, Melhem M, Fukushima K, Bollo E. 2006. Extracellular enzymatic activities in Cryptococcus neoformans strains isolated from AIDS patients in different countries. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 23:216–220. 10.1016/S1130-1406(06)70047-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Portela MB, Kneipp LF, Ribeiro de Souza IP, Holandino C, Alviano CS, Meyer-Fernandes JR, de Araújo Soares RM. 2010. Ectophosphatase activity in Candida albicans influences fungal adhesion: study between HIV-positive and HIV-negative isolates. Oral Dis. 16:431–437. 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2009.01644.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kiffer-Moreira T, de Sá Pinheiro AA, Alviano WS, Barbosa FM, Souto-Padrón T, Nimrichter L, Rodrigues ML, Alviano CS, Meyer-Fernandes JR. 2007. An ectophosphatase activity in Candida parapsilosis influences the interaction of fungi with epithelial cells. FEMS Yeast Res. 7:621–628. 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2007.00223.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Arnold WN, Mann LC, Sakai KH, Garrison RG, Coleman PD. 1986. Acid phosphatases of Sporothrix schenckii. J. Gen. Microbiol. 132:3421–3432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bernard M, Mouyna I, Dubreucq G, Debeaupuis JP, Fontaine T, Vorgias C, Fuglsang C, Latgé JP. 2002. Characterization of a cell-wall acid phosphatase (PhoAp) in Aspergillus fumigatus. Microbiology 148:2819–2829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Puri RV, Reddy PV, Tyagi AK. 2013. Secreted acid phosphatase (SapM) of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is indispensable for arresting phagosomal maturation and growth of the pathogen in guinea pig tissues. PLoS One 8:e70514. 10.1371/journal.pone.0070514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Saha AK, Dowling JN, Pasculle AW, Glew RH. 1988. Legionella micdadei phosphatase catalyzes the hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate in human neutrophils. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 265:94–104. 10.1016/0003-9861(88)90375-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shakarian AM, Joshi MB, Ghedin E, Dwyer DM. 2002. Molecular dissection of the functional domains of a unique, tartrate-resistant, surface membrane acid phosphatase in the primitive human pathogen Leishmania donovani. J. Biol. Chem. 277:17994–18001. 10.1074/jbc.M200114200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Collopy-Junior I, Esteves FF, Nimrichter L, Rodrigues ML, Alviano CS, Meyer-Fernandes JR. 2006. An ectophosphatase activity in Cryptococcus neoformans. FEMS Yeast Res. 6:1010–1017. 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2006.00105.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Orkwis BR, Davies DL, Kerwin CL, Sanglard D, Wykoff DD. 2010. Novel acid phosphatase in Candida glabrata suggests selective pressure and niche specialization in the phosphate signal transduction pathway. Genetics 186:885–895. 10.1534/genetics.110.120824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kneipp LF, Magalhães AS, Abi-Chacra EA, Souza LO, Alviano CS, Santos AL, Meyer-Fernandes JR. 2012. Surface phosphatase in Rhinocladiella aquaspersa: biochemical properties and its involvement with adhesion. Med. Mycol. 50:570–578. 10.3109/13693786.2011.653835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kneipp LF, Rodrigues ML, Holandino C, Esteves FF, Souto-Padrón T, Alviano CS, Travassos LR, Meyer-Fernandes JR. 2004. Ectophosphatase activity in conidial forms of Fonsecaea pedrosoi is modulated by exogenous phosphate and influences fungal adhesion to mammalian cells. Microbiology 150:3355–3362. 10.1099/mic.0.27405-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dick CF, Dos-Santos AL, Meyer-Fernandes JR. 2011. Inorganic phosphate as an important regulator of phosphatases. Enzyme Res. 2011:103980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Oshima Y. 1997. The phosphatase system in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Genet. Syst. 72:323–334. 10.1266/ggs.72.323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vogel K, Hinnen A. 1990. The yeast phosphatase system. Mol. Microbiol. 4:2013–2017. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00560.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rodrigues ML, Djordjevic JT. 2012. Unravelling secretion in Cryptococcus neoformans: more than one way to skin a cat. Mycopathologia 173:407–418. 10.1007/s11046-011-9468-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rodrigues ML, Nakayasu ES, Oliveira DL, Nimrichter L, Nosanchuk JD, Almeida IC, Casadevall A. 2008. Extracellular vesicles produced by Cryptococcus neoformans contain protein components associated with virulence. Eukaryot. Cell 7:58–67. 10.1128/EC.00370-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sorgo AG, Heilmann CJ, Dekker HL, Brul S, de Koster CG, Klis FM. 2010. Mass spectrometric analysis of the secretome of Candida albicans. Yeast 27:661–672. 10.1002/yea.1775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Weber SS, Parente AF, Borges CL, Parente JA, Bailão AM, de Almeida Soares CM. 2012. Analysis of the secretomes of Paracoccidioides mycelia and yeast cells. PLoS One 7:e52470. 10.1371/journal.pone.0052470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Phillips SE, Vincent P, Rizzieri KE, Schaaf G, Bankaitis VA, Gaucher EA. 2006. The diverse biological functions of phosphatidylinositol transfer proteins in eukaryotes. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 41:21–49. 10.1080/10409230500519573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Curwin AJ, Fairn GD, McMaster CR. 2009. Phospholipid transfer protein Sec14 is required for trafficking from endosomes and regulates distinct trans-Golgi export pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 284:7364–7375. 10.1074/jbc.M808732200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chayakulkeeree M, Johnston SA, Oei JB, Lev S, Williamson PR, Wilson CF, Zuo X, Leal AL, Vainstein MH, Meyer W, Sorrell TC, May RC, Djordjevic JT. 2011. SEC14 is a specific requirement for secretion of phospholipase B1 and pathogenicity of Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol. Microbiol. 80:1088–1101. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07632.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Eigenheer RA, Jin Lee Y, Blumwald E, Phinney BS, Gelli A. 2007. Extracellular glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored mannoproteins and proteases of Cryptococcus neoformans. FEMS Yeast Res. 7:499–510. 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2006.00198.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Biondo C, Mancuso G, Midiri A, Bombaci M, Messina L, Beninati C, Teti G. 2006. Identification of major proteins secreted by Cryptococcus neoformans. FEMS Yeast Res. 6:645–651. 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2006.00043.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rigden DJ. 2008. The histidine phosphatase superfamily: structure and function. Biochem. J. 409:333–348. 10.1042/BJ20071097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bevis BJ, Glick BS. 2002. Rapidly maturing variants of the Discosoma red fluorescent protein (DsRed). Nat. Biotechnol. 20:83–87. 10.1038/nbt0102-83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Monod M, Haguenauer-Tsapis R, Rauseo-Koenig I, Hinnen A. 1989. Functional analysis of the signal-sequence processing site of yeast acid phosphatase. Eur. J. Biochem. 182:213–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Harsay E, Schekman R. 2002. A subset of yeast vacuolar protein sorting mutants is blocked in one branch of the exocytic pathway. J. Cell Biol. 156:271–285. 10.1083/jcb.200109077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Islam A, Li SS, Oykhman P, Timm-McCann M, Huston SM, Stack D, Xiang RF, Kelly MM, Mody CH. 2013. An acidic microenvironment increases NK cell killing of Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii by enhancing perforin degranulation. PLoS Pathog. 9:e1003439. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ng AW, Bidani A, Heming TA. 2004. Innate host defense of the lung: effects of lung-lining fluid pH. Lung 182:297–317. 10.1007/s00408-004-2511-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Himmelreich U, Allen C, Dowd S, Malik R, Shehan BP, Mountford C, Sorrell TC. 2003. Identification of metabolites of importance in the pathogenesis of pulmonary cryptococcoma using nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Microbes Infect. 5:285–290. 10.1016/S1286-4579(03)00028-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Baker LG, Specht CA, Donlin MJ, Lodge JK. 2007. Chitosan, the deacetylated form of chitin, is necessary for cell wall integrity in Cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryot. Cell 6:855–867. 10.1128/EC.00399-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Reese AJ, Yoneda A, Breger JA, Beauvais A, Liu H, Griffith CL, Bose I, Kim MJ, Skau C, Yang S, Sefko JA, Osumi M, Latge JP, Mylonakis E, Doering TL. 2007. Loss of cell wall alpha(1-3) glucan affects Cryptococcus neoformans from ultrastructure to virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 63:1385–1398. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05551.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. James PG, Cherniak R, Jones RG, Stortz CA, Reiss E. 1990. Cell-wall glucans of Cryptococcus neoformans Cap 67. Carbohydr. Res. 198:23–38. 10.1016/0008-6215(90)84273-W [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gilbert NM, Donlin MJ, Gerik KJ, Specht CA, Djordjevic JT, Wilson CF, Sorrell TC, Lodge JK. 2010. KRE genes are required for beta-1,6-glucan synthesis, maintenance of capsule architecture and cell wall protein anchoring in Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol. Microbiol. 76:517–534. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07119.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mouyna I, Fontaine T, Vai M, Monod M, Fonzi WA, Diaquin M, Popolo L, Hartland RP, Latgé JP. 2000. Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored glucanosyltransferases play an active role in the biosynthesis of the fungal cell wall. J. Biol. Chem. 275:14882–14889. 10.1074/jbc.275.20.14882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Popolo L, Vai M, Gatti E, Porello S, Bonfante P, Balestrini R, Alberghina L. 1993. Physiological analysis of mutants indicates involvement of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae GPI-anchored protein gp115 in morphogenesis and cell separation. J. Bacteriol. 175:1879–1885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ram AF, Kapteyn JC, Montijn RC, Caro LH, Douwes JE, Baginsky W, Mazur P, van den Ende H, Klis FM. 1998. Loss of the plasma membrane-bound protein Gas1p in Saccharomyces cerevisiae results in the release of β1,3-glucan into the medium and induces a compensation mechanism to ensure cell wall integrity. J. Bacteriol. 180:1418–1424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Leuthner B, Aichinger C, Oehmen E, Koopmann E, Muller O, Muller P, Kahmann R, Bolker M, Schreier PH. 2005. A H2O2-producing glyoxal oxidase is required for filamentous growth and pathogenicity in Ustilago maydis. Mol. Genet. Genomics 272:639–650. 10.1007/s00438-004-1085-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lian T, Simmer MI, D’Souza CA, Steen BR, Zuyderduyn SD, Jones SJ, Marra MA, Kronstad JW. 2005. Iron-regulated transcription and capsule formation in the fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol. Microbiol. 55:1452–1472. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04474.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cadieux B, Lian T, Hu G, Wang J, Biondo C, Teti G, Liu V, Murphy ME, Creagh AL, Kronstad JW. 2013. The mannoprotein Cig1 Supports iron acquisition from heme and virulence in the pathogenic fungus Cryptococcus neoformans. J. Infect. Dis. 207:1339–1347. 10.1093/infdis/jit029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. van Niel G, Porto-Carreiro I, Simoes S, Raposo G. 2006. Exosomes: a common pathway for a specialized function. J. Biochem. 140:13–21. 10.1093/jb/mvj128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]