Abstract

Sandflies transmit pathogens of leishmaniasis. The natural infection of sandflies by Leishmania (Viannia) was assessed in municipalities, in the state of Paraná, in Southern Brazil. Sandflies were collected with Falcão and Shannon traps. After dissection in search of flagellates in digestive tubes and identification of the species, female sandflies were submitted to the Multiplex Polymerase Chain Reaction (multiplex PCR) for detection of the fragment of the kDNA of Leishmania (Viannia) and the fragment from the IVS6 cacophony gene region of the phlebotomine insects. The analysis was performed in pools containing seven to 12 guts from females of the same species. A total of 510 female sandflies were analyzed, including nine Migonemyia migonei, 17 Pintomyia fischeri, 216 Nyssomyia neivai, and 268 Nyssomyia whitmani. Although none of the females was found naturally infected by flagellates through dissection, the fragment of DNA from Leishmania (Viannia) was shown by multiplex PCR in one sample of Ny. neivai (0.46%) and three samples of Ny. whitmani (1.12%). It was concluded that Ny. neivai and Ny. whitmani are susceptible to Leishmania infection, and that multiplex PCR can be used in epidemiological studies to detect the natural infection of the sandfly vector, because of its sensitivity, specificity and feasibility.

Keywords: Cutaneous leishmaniasis, Sandfly, PCR, Leishmania, Nyssomyia whitmani, Nyssomyia neivai

Abstract

Flebotomíneos transmitem os patógenos das leishmanioses. Foi avaliada a infecção natural de flebotomíneos por Leishmania (Viannia) em municípios do Estado do Paraná, sul do Brasil. Os flebotomíneos foram coletados com armadilhas de Falcão e Shannon. Após dissecação para pesquisa de flagelados no tubo digestório e identificação das espécies, as fêmeas de flebotomíneos foram submetidas a Multiplex Reação em Cadeia da Polimerase (multiplex PCR) para a detecção do fragmento do kDNA de Leishmania (Viannia) e do fragmento do gene IVS6 da cacofonia de flebotomíneos. A análise foi realizada em pools contendo sete a 12 tubos digestórios de fêmeas da mesma espécie. Um total de 510 fêmeas foram analisadas, incluindo nove Migonemyia migonei, 17 Pintomyia fischeri, 216 Nyssomyia neivai e 268 Nyssomyia whitmani. Embora nenhuma fêmea tenha sido encontrada naturalmente infectada com flagelados pela dissecação, o fragmento de DNA de Leishmania (Viannia) foi mostrado por multiplex PCR em uma amostra de Ny. neivai (0,46%) e três amostras de Ny. whitmani (1,12%). Conclui-se que Ny. neivai e Ny. whitmani são suscetíveis à infecção por Leishmania, e que multiplex PCR, devido à sua sensibilidade, especificidade e viabilidade, pode ser utilizada em estudos epidemiológicos para a detecção da infecção natural do inseto vetor.

INTRODUCTION

Knowledge of the fauna composition, behavior, rates of natural infection of the sandfly, Leishmania species identification, and environmental characteristics of endemic areas are essential for the public-health services responsible for protecting populations that live in areas in which leishmaniasis is endemic. Leishmaniasis has worldwide propagation. In Brazil, cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) has been reported in all states3.

Cases of CL have increased significantly since the 1980s, and are appearing over wider areas in the State of Paraná, in the South of Brazil28,29. This disease has been recorded in occupied areas for more than a century, even in urban areas, contrary to expectations that human pressure would eliminate natural foci and reduce the incidence of this endemic disease16,33,46. The organization of rural areas in the Brazilian colonial period created environmental conditions that clearly favor CL transmission28.

There are several reports of Leishmania detection in sandflies in endemic CL areas in Brazil and in the world1,32,41. However, considering the wide geographical distribution of this dermatosis in the Americas47, knowledge of the natural infection rate of sandflies is still insufficient to estimate the risk of Leishmania infection in many endemic areas.

Given the occurrence of autochthonous CL cases in several municipalities, in the state of Paraná, natural infection rates of sandflies by Leishmania (Viannia) were investigated, in order to identify the species of Leishmania present in locations where cases of this disease had been reported.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Sandfly collection: Sandflies were collected in the localities of Recanto Marista, Água Azul Farm and Flor de Maio Grange, in the municipalities of Doutor Camargo, Fênix and Mandaguari, respectively, in the state of Paraná, where CL cases had been reported. Sandflies were collected from January through September 2006, from 6 p.m. to 6 a.m., with Falcão light traps and a Shannon trap, installed in woods, domiciles, peridomicile and domestic-animal shelters (cattle shelter and pigsty)30. The collected insects were kept alive for further dissection and observation of the natural infection by flagellates.

Dissection and identification of sandflies: The dissection was carried out under a stereoscope; the legs and wings were removed and the dissection was carried out by making two incisions in the distal portion of the abdomen and, with zigzag movements, the digestive tubes were removed and examined under an optical microscope (400 x) in the search for flagellates and the identification of the species of the sandfly30. The nomenclature of the species follows GALATI12.

After dissection and identification30 of species, digestive tubes were stored at -18 °C in tubes containing 150 µL STE buffer (0.1 M NaCl, 10 mM Tris-base; Na2EDTA-2H2O 1 mM, pH 8.0), each containing seven to 12 guts from females of the same species.

Extraction of DNA: The samples were macerated, and DNA was extracted with a solution of guanidine isothiocyanate and phenol, and hydrated in 20 µL of ultra-pure H2O31. For each group of 22 samples submitted for DNA extraction, one negative control (male sandflies) and one positive control [male sandflies plus 104 L. (V.) braziliensis promastigotes] were used.

Multiplex PCR: Two pairs of primers were used: MP3H (5′-GAA CGG GGT TTC TGT ATG C-3′) and MP1L (5′-TAC TCC CCG ACA TGC CTC TG-3′)18 to amplify a fragment of 70-bp from the mini circle region of the kinetoplast (kDNA) of the Leishmania (Viannia), and 5Llcac (5′-TGG CCG AAC ATA ATG TTA G-3′) and 3Llcac (5′-CCA CGA ACA AGT TCA ACA TC-3′)17 to amplify a fragment of 220-bp from the IVS6 cacophony gene region of the phlebotomine insects.

The PCR reaction mixture (final volume 25 µL) was composed of 0.5 µM of each of the primers (Invitrogen Life Technologies, São Paulo, Brazil), 0.2 mM dNTP (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 1U Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase, (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1X enzyme buffer, and 2 µL DNA template. The amplification was carried out in a PC Thermocycler (Biometra, Germany) at 94 °C for seven min to activate the enzyme, followed by 30 cycles, each divided into three stages, of denaturation (1.5 min at 95 °C), annealing (1.5 min at 57 °C), and polymerization (two min at 72 °C). After this, the extension was continued for a further 10 min at 72 °C, and the tubes were then kept at 4 °C until analysis31. The amplification products were submitted to electrophoresis in 2% of agarose gel (Invitrogen, Paisley, Scotland, UK) stained with 0.1 µg/mL ethidium bromide, at 10-15 V/cm. The presence of bands was observed in a transilluminator (Macro Vue™ UV-20, Hoefer). For every five samples, one positive control [reaction mixture plus L. (V.) braziliensis DNA] and one negative control (reaction mixture plus water) were added.

RESULTS

In total, 510 (52 pools) female sandflies were analyzed by dissection and multiplex PCR, including nine Migonemyia migonei (one pool), 17 Pintomyia fischeri (two pools), 216 Nyssomyia neivai (22 pools), and 268 Nyssomyia whitmani (27 pools) (Table 1). A total of 244 female sandflies were collected at Recanto Marista, 107 at Água Azul Farm, and 159 at Flor de Maio Grange (Table 1).

Table 1. Sandflies collected in Recanto Marista, Água Azul Farm, and Flor de Maio Grange, in Southern Brazil, from January to September, 2006.

| Specimens/Localities (Municipalities) | Recanto Marista (Doutor Camargo) | Água Azul Farm (Fênix) | Flor de Maio Grange (Mandaguari) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Migonemyia migonei | Na | 9 | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| Positive pools / Poolsb | 0/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/1 | |

| Nyssomyia whitmani | Na | 19 | 97 | 152 | 268 |

| Positive pools / Poolsb | 0/2 | 1/10 | 2/15 | 3/27 | |

| Nyssomyia neivai | Na | 216 | 0 | 0 | 216 |

| Positive pools / Poolsb | 1/22 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/22 | |

| Pintomyia fischeri | Na | 0 | 10 | 7 | 17 |

| Positive pools / Poolsb | 0/0 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/2 | |

| Total | Na | 244 | 107 | 159 | 510 |

| Positive pools / Poolsb | 1/25 | 1/11 | 2/16 | 4/52 | |

Number of Specimens;

Number of positive pools/number of pools composed. Each pool contained seven to 12 guts from females of the same species.

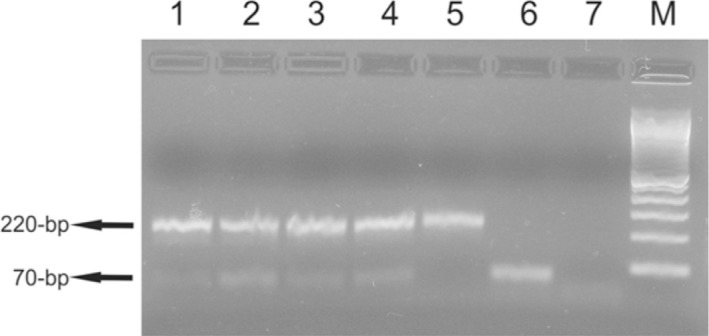

All 52 sandfly pools contained the 220-bp fragment from the IVS6 cacophony gene region of the sandflies, and four pools (7.7%) showed the 70-bp fragment from the mini circle kDNA of Leishmania (Viannia) (Fig. 1). The minimal infection rate of Ny. neivai was 0.46% (1/216), and of Ny. whitmani was 1.12% (3/268). At Recanto Marista one Ny. neivai pool with Leishmania infection was detected on the porch of a domicile; at Água Azul Farm, one Ny. whitmani pool was detected in the peridomicile (near the woods ); and at Flor de Maio Grange, two Ny. whitmani pools were detected, one on the porch of a domicile and another from a domestic-animal shelter. The minimal infection rate of Recanto Marista was 0.41% (1/244), of Flor de Maio Grange was 1.26% (2/159), and at Água Azul Farm was 0.93% (1/107).

Fig 1 -. Multiplex PCR in 2% of agarose gel showing fragments of 70-bp and 220-bp. The fragment of 70-bp of the kDNA mini circle region of subgenus Leishmania (Viannia) were amplified with MP3H and MP1L primers. The fragment of 220-bp of the IVS6 cacophony gene region of the phlebotomine insects were amplified with 5Llcac and 3Llcac primers. Lane 1, Ny. whitmani DNA sample collected in Fênix; lanes 2, 3 and 5, Ny. whitmani DNA samples collected in Mandaguari; lane 4, Ny. neivai DNA sample collected in Doutor Camargo; lane 6, positive control [DNA from L. (V.) braziliensis promastigotes]; lane 7, negative control (all reagents without DNA). M, 100-bp molecular marker (Invitrogen Life Technologies, São Paulo, Brazil).

DISCUSSION

Mi. migonei, Pi. fischeri, Ny. neivai, and Ny. whitmani are frequently found in Brazil1,2,4,31,34,35,43,46. Both species detected with Leishmania infection are widely propagated in Brazil4,5,6,9,20,21 and in the state of Paraná, where either Ny. whitmani or Ny. neivai predominate, depending on environmental characteristics26,42,43,46.

Although no flagellates were detected in the dissected sandfly digestive tubes, DNA from Leishmania (Viannia) was found in 0.78% (4/510), indicating that at least one infected sandfly was present in each positive pool. The infected specimens were collected at sites near a riparian forest, which is inhabited by small wild mammals (e.g. rodents, armadillo) that are possible natural reservoirs of Leishmania. These locations show favorable environment for the formation of sandfly-breeding sites. Furthermore, the domestic animals are highly attractive blood sources for female sandflies37,44,45. Natural infection by Leishmania has been recorded in Pi. fischeri 23,36,38, Mi. migonei 2,7,34, Ny. neivai 8,22,31,41,47, and Ny. whitmani 1,4,11,19, by dissection or PCR, in several localities in many of the Brazilian states.

Natural infection rates of sandflies by Leishmania vary widely: 15.68% in Venezuela by PCR13, 0.83% and 7.14%4, and 18.2%23, in Brazil, by PCR4, and 1.4% and 2.6%, in Peru, by dissection15. Studies on natural infection rates have revealed that PCR is more sensitive and specific than dissection showing the presence of Leishmania in sandflies10,27,39,40. This method has often been used in areas where sandfly infection rates are low27,31, due to its sensitivity (it is able to detect the presence of a single parasite), specificity (independently of the number, location and stage of flagellates in the digestive tubes of the vector)25,27,34, rapidity, and ease of performance enabling it to be used in leishmaniasis epidemiological surveillance24. The dissection of sandflies for the detection of flagellates in the digestive tubes needs confirmation by Leishmania in vitro, cultivation or inoculation in laboratory animals27 while molecular methods allow the identification of Leishmania species, isolated in cultures from patients or reservoirs, as well from sandflies25,27.

Several primers have been used14,27,34, however, the primers used in this study have been tested successfully in diagnosis and detection of naturally infected sandflies, besides having good sensitivity [8 fg/µL of Leishmania (Viannia)]31.

The advantage of employing the multiplex PCR technique is that, in addition to the primers for detection of Leishmania (Viannia), the pair of primers used for internal control can assess the presence of probable interference from digestive contents of insects, which can inhibit the detection of Leishmania 31,34.

The results show the susceptibility of sandflies to Leishmania strains. The minimum infection rates in Ny. neivai (0.46%, 1/216) and Ny. whitmani (1.12%, 3/268) are low, and might explain the low CL endemicity in the municipalities in question. Multiplex PCR, because of its sensitivity, specificity and feasibility, can be used in epidemiological studies to detect the natural infection of the sandfly vector.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Colégio Marista, Água Azul Farm, and Flor de Maio Grange, for the permission granted to conduct the assessments, and for logistical support. Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq Process 410550/2006-0), Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), and Fundação Araucária for their financial support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Azevedo ACR, Rangel EF, Costa EM, David J, Vasconcelos AW, Lopes UG. Natural infection of Lutzomyia (Nyssomyia) whitmani (Antunes & Coutinho, 1939) by Leishmania of the braziliensis complex in Baturité, Ceará State, northeast Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1990;85:251. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761990000200021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azevedo ACR, Rangel EF, Queiroz RG. Lutzomyia migonei (França, 1920) naturally infected with peripylarian flagellates in Baturité, a focus of cutanous leishmaniasis in Ceará State, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1990;85:479. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761990000400016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Manual de vigilância da leishmaniose tegumentar americana. Available from: http://goo.gl/mPcbz.

- 4.Carvalho GM, Andrade JD, Filho, Falcão AL, Rocha-Lima AC, Gontijo CM. Naturally infected Lutzomyia sand flies in a Leishmania-endemic area of Brazil. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2008;8:407–14. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2007.0180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carvalho MSL, Bredt A, Meneghin ERS, Oliveira C. Flebotomíneos (Diptera: Psychodidae) em áreas de ocorrência de leishmaniose tegumentar americana no Distrito Federal, Brasil, 2006 a 2008. Epidemiol Serv Saúde. 2010;19:227–37. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carvalho SMS, Santos PRB, Lanza H, Brandão SP., Filho Diversidade de flebotomíneos no município de Ilhéus, Bahia. Epidemiol Serv Saúde. 2010;19:239–44. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carvalho MR, Valença HF, Silva FJ, Pita-Pereira D, Araújo-Pereira T, Britto C, et al. Natural Leishmania infantum infection in Migonemyia migonei (França, 1920) (Diptera: Psychodidae: Phlebotominae) the putative vector of visceral leishmaniasis in Pernambuco State, Brazil. Acta Trop. 2010;116:108–10. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Córdoba-Lanús E, De Grosso ML, Piñero JE, Valladares B, Salomón OD. Natural infection of Lutzomyia neivai with Leishmania spp. in northwestern Argentina. Acta Trop. 2006;98:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Costa SM, Cechinel M, Bandeira V, Zannuncio JC, Lainson R, Rangel EF. Lutzomyia (Nyssomyia) whitmani s.l. (Antunes & Coutinho, 1939) (Diptera: Psychodidae: Phlebotominae): geographical distribution and the epidemiology of American cutaneous leishmaniasis in Brazil: mini-review. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2007;102:149–53. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762007005000016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dinesh DS, Kar SK, Kishore K, Palit A, Verma N, Gupta AK, et al. Screening sandflies for natural infection with Leishmania donovani, using a non-radioactive probe based on the total DNA of the parasite. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2000;94:447–51. doi: 10.1080/00034983.2000.11813563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galati EAB, Nunes VLB, Dorval MEC, Oshiro ET, Cristaldo G, Espíndola MA, et al. Estudo dos flebotomíneos (Diptera, Pychodidae) em área de leishmaniose tegumentar, no Estado de Mato Grosso do Sul, Brasil. Rev Saúde Pública. 1996;30:115–28. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89101996000200002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galati EAB. Morfologia e taxonomia. In: Rangel EF, Lainson R, editors. Flebotomíneos do Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: Fiocruz; 2003. pp. 23–51. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jorquera A, González R, Marchán-Marcano E, Oviedo M, Matos M. Multiplex-PCR for detection of natural Leishmania infection in Lutzomyia spp. captured in an endemic region for cutaneous leishmaniasis in state of Sucre, Venezuela. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2005;100:45–8. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762005000100008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kato H, Uezato H, Katakura K, Calvopiña M, Marco JD, Barroso PA, et al. Detection and identification of Leishmania species within naturally infected sand flies in the Andean areas of Ecuador by a polymerase chain reaction. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;72:87–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kato H, Gomez EA, Cáceres AG, Vargas F, Mimori T, Yamamoto K, et al. Natural infections of man-biting sand flies by Leishmania and Trypanosoma species in the northern Peruvian Andes. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2011;11:515–21. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2010.0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lima AP, Minelli L, Teodoro U, Comunello E. Tegumentary leishmaniasis distribution by satellite remote sensing imagery, in Paraná State, Brazil. An Bras Dermatol. 2002;77:681–92. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lins RM, Oliveira SG, Souza NA, Queiroz RG, Justiniano SC, Ward RD, et al. Molecular evolution of the cacophony IVS6 region in sandflies. Insect Mol Biol. 2002;11:117–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2002.00315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lopez M, Inga R, Cangalaya M, Echevarria J, Llanos-Cuentas A, Orrego C, et al. Diagnosis of Leishmania using the polymerase chain reaction: a simplified procedure for field work. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;49:348–56. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1993.49.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luz E, Membrive N, Castro EA, Dereure J, Pratlong F, Dedet JA, et al. Lutzomyia whitmani (Diptera: Psychodidae) as vector of Leishmania (V.) braziliensis in Paraná State, southern Brazil. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2000;94:623–31. doi: 10.1080/00034983.2000.11813585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marcondes CB, Lozovei AL, Vilela JH. Distribuição geográfica de flebotomíneos do complexo Lutzomyia intermedia (Lutz & Neiva, 1912) (Diptera, Psychodidae) Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 1998;31:51–8. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86821998000100007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marcondes CB, Conceição MBE, Portes MGT, Simão BP. Phlebotomine sandflies in a focus of dermal leishmaniasis in the eastern region of the Brazilian state of Santa Catarina - preliminary results (Diptera: Psychodidae) Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2005;38:353–5. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822005000400016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marcondes CB, Bittencourt IA, Stoco PH, Eger I, Grisard EC, Steindel M. Natural infection of Nyssomyia neivai (Pinto, 1926) (Diptera: Psychodidae, Phlebotominae) by Leishmania (Viannia) spp. in Brazil. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103:1093–7. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Margonari C, Soares RP, Andrade JD, Filho, Xavier DC, Saraiva L, Fonseca AL, et al. Phlebotomine sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) and Leishmania infection in Gafanhoto Park, Divinópolis, Brazil. J Med Entomol. 2010;47:1212–9. doi: 10.1603/me09248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martín-Sánchez J, Gállego M, Barón S, Castillejo S, Morillas-Marques F. Pool screen PCR for estimating the prevalence of Leishmania infantum infection in sandflies (Diptera: Nematocera, Phlebotomidae) Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2006;100:527–32. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Medeiros ACR, Rodrigues SS, Roselino AMF. Comparison of the specificity of PCR and the histopathological detection of Leishmania for the diagnosis of American cutaneous leishmaniasis. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2002;35:421–4. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2002000400002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Membrive NA, Rodrigues G, Membrive U, Monteiro WM, Neitzke HC, Lonardoni MVC, et al. Flebotomíneos de municípios do norte do estado do Paraná, sul do Brasil. Entomol Vectores. 2004;11:673–80. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Michalsky ÉM, Fortes-Dias CL, Pimenta PFP, Secundino NFC, Dias ES. Assessment of PCR in the detection of Leishmania spp in experimentally infected individual phlebotomine sandflies (Diptera: Psychodidae: Phlebotominae) Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2002;44:255–9. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652002000500004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Monteiro WM, Neitzke HC, Lonardoni MVC, Silveira TGV, Ferreira MEMC, Teodoro U. Distribuição geográfica e características epidemiológicas da leishmaniose tegumentar americana em áreas de colonização antiga do Estado do Paraná, Sul do Brasil. Cad Saúde Pública. 2008;24:1291–303. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2008000600010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monteiro WM, Neitzke HC, Silveira TGV, Lonardoni MVC, Teodoro U, Ferreira MEMC. Pólos de produção de leishmaniose tegumentar americana no norte do Estado do Paraná, Brasil. Cad Saúde Pública. 2009;25:1083–92. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2009000500015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neitzke HC, Scodro RBL, Reinhold-Castro KR, Dias-Sversutti AC, Silveira TGV, Teodoro U. Pesquisa de infecção natural de flebotomíneos por Leishmania, no Estado do Paraná. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2008;41:17–22. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822008000100004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oliveira DM, Reinhold-Castro KR, Bernal MVZ, Legriffon CMO, Lonardoni MVC, Teodoro U, et al. Natural infection of Nyssomyia neivai by Leishmania (Viannia) spp. in the state of Paraná, southern Brazil, detected by multiplex polymerase chain reaction. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2011;11:137–43. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2009.0218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parvizi P, Ready PD. Nested PCRs and sequencing of nuclear ITS-rDNA fragments detect three Leishmania species of gerbils in sandflies from Iranian foci of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13:1159–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pessoa SB, Barreto MP. Rio de Janeiro: Imprensa Nacional - São Paulo: Serviço de Parasitologia, Departamento de Medicina, Faculdade de São Paulo; 1948. Leishmaniose tegumentar americana. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pita-Pereira D, Alves CR, Souza MB, Brazil RP, Bertho AL, Figueiredo-Barbosa A, et al. Identification of naturally infected Lutzomyia intermedia and Lutzomyia migonei with Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis in Rio de Janeiro (Brazil) revealed by a PCR multiplex non-isotopic hybridisation assay. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2005;99:905–13. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2005.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pita-Pereira D, Souza GD, Zwetsch A, Alves CR, Britto C, Rangel EF. First report of Lutzomyia (Nyssomyia) neivai (Diptera: Psychodidae: Phlebotominae) naturally infected by Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis in a periurban area of south Brazil using a multiplex polymerase chain reaction assay. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80:593–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pita-Pereira D, Souza GD, Pereira TA, Zwetsch A, Britto C, Rangel EF. Lutzomyia (Pintomyia) fischeri (Diptera: Psychodidae: Phlebotominae), a probable vector of American cutaneous leishmaniasis: detection of natural infection by Leishmania (Viannia) DNA in a specimens from the municipality of Porto Alegre (RS), Brazil, using multiplex PCR assay. Acta Trop. 2011;120:273–5. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reinhold-Castro KR, Scodro RBL, Dias-Sversutti AC, Neitzke HC, Rossi RM, Kuhl JB, et al. Avaliação de medidas de controle de flebotomineos. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2008;41:269–76. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822008000300009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rocha LSO, Santos CB, Falqueto A, Grimaldi Jr G, Cupolillo E. Molecular biological identification of monoxenous trypanosomatids and Leishmania from antropophilic sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) in Southeast Brazil. Parasitol Res. 2010;107:465–8. doi: 10.1007/s00436-010-1903-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rodriguez N, Aguilar CM, Barrios MA, Barker DC. Detection of Leishmania braziliensis in naturally infected individual sandflies by the polymerase chain reaction. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1999;93:47–9. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(99)90176-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rodriguez N, Lima H, Aguilar CM, Rodriguez A, Barker DC, Convit J. Molecular epidemiology of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Venezuela. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2002;96((Suppl 1)):105–9. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(02)90060-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saraiva L, Carvalho GML, Gontijo CMF, Quaresma PF, Lima ACVMR, Falcão AL, et al. Natural infection of Lutzomyia neivai and Lutzomyia sallesi (Diptera: Psychodidae) by Leishmania infantum chagasi in Brazil. J Med Entomol. 2009;46:1159–63. doi: 10.1603/033.046.0525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Silva AM, Camargo NJ, Santos DR, Massafera R, Ferreira AC, Postai C, et al. Diversidade, distribuição e abundância de flebotomíneos (Diptera: Psychodidae) no Paraná. Neotrop Entomol. 2008;37:209–25. doi: 10.1590/s1519-566x2008000200017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Teodoro U, Santos DR, Santos AR, Oliveira O, Poiani LP, Silva AM, et al. Preliminary information on sandflies in the north of Paraná State, Brazil. Rev Saúde Publica. 2006;40:327–30. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102006000200022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Teodoro U, Lonardoni MVC, Silveira TGV, Dias AC, Abbas M, Alberton D, et al. Luz e galinhas como fatores de atração de Nyssomyia whitmani em ambiente rural, Paraná, Brasil. Rev Saúde Publica. 2007;41:383–8. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102007000300009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Teodoro U, Santos DR, Santos AR, Oliveira O, Poiani LP, Kuhl JB, et al. Avaliação de medidas de controle de flebotomineos no norte do Estado do Paraná, Brasil. Cad Saúde Publica. 2007;23:2597–604. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2007001100007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Teodoro U, Santos DR, Silva AM, Massafera R, Imazu LE, Monteiro WM, et al. Fauna de flebotomíneos em municípios do norte pioneiro do estado do Paraná, Brasil. Rev Patol Trop. 2010;39:322–30. [Google Scholar]

- 47.World Health Organization, Leishmaniasis Available from: http://goo.gl/PiM9n.