Supplemental digital content is available in the text.

Key Words: Cervical cancer, HPV, Young female, Social networking sites, Advocacy

Abstract

Objectives

Cervical cancer (CC) incidence and mortality among young women have been increasing in Japan. To develop effective measures to combat this, we assessed the feasibility of using a social networking site (SNS) to recruit a representative sample of young women to conduct a knowledge and attitude study about CC prevention via an internet-based questionnaire.

Methods

From July 2012 to March 2013, advertising banners targeting women aged 16 to 35 years in Kanagawa Prefecture were placed on Facebook in a similar manner as an Australian (AUS) study conducted in 16- to 25-year-olds in 2010 and on a homepage to advertise our CC advocacy activities. Eligible participants were emailed instructions for accessing our secure Web site where they completed an online survey including demographics, awareness, and knowledge of human papillomavirus (HPV) and CC. Data for the study population were compared with the general Japanese population and the AUS study.

Results

Among 394 women who expressed interest, 243 (62%) completed the survey, with 52% completing it via Facebook. Women aged 26 to 35 years, living in Yokohama City, with an education beyond high school, were overrepresented. Participants had high awareness and knowledge of HPV and CC, comparable with the AUS study participants. However, the self-reported HPV vaccination rate (22% among participants aged 16–25 years) and the recognition rate of the link between smoking and CC (31%) were significantly lower than in the AUS study (58% and 43%, respectively) (P < 0.05). Significant predictors of high knowledge scores about HPV included awareness of HPV vaccine (P < 0.001) and self-reported HPV vaccination (P < 0.05).

Conclusions

The SNS and homepage are efficient methods to recruit young women into health surveys, which can effectively be performed online. A nationwide survey using SNSs would be an appropriate next step to better understand the current lack of uptake of the national HPV vaccine program by young women in Japan.

The increasing incidence and mortality rates of cervical cancer (CC) among young Japanese (JPN) women are a serious health problem.1,2 This situation is thought to be a result of low uptake of the CC cytology screening program. With a population of approximately 65,600,000 women, Japan reported in 2007 that 8867 women were newly diagnosed with invasive CC, whereas 2737 women died from the disease in 2011.1 To establish effective prevention strategies in Japan, we require a broader understanding of reproductive and sexual health behaviors among young people, because the risk for CC begins at the first intercourse.3 The recruitment of representative samples of young people is challenging as this population is increasingly mobile and, in general, indifferent to medical issues. Moreover, traditional strategies, such as random digit dialing and media advertising campaigns, have limitations, including low participation rates due to reduced landlines and high costs.4–7 Recently, a study conducted by us in Australia showed that using the social networking site (SNS), Facebook (FB), was an effective strategy to identify a representative sample of young women.8,9 This Australian (AUS) study demonstrated the potential of using SNSs in a cost-effective way to engage young women in health research and to penetrate nonurban communities. In Japan, SNSs, including FB, are rapidly being embraced among younger generations with 72% in their teens and 64% in their 20s being reported as regular users.10 Furthermore, around 42% of JPN women aged 10 to 39 years have their own FB account with 50% of them being daily users.11

In this study, our objectives were to measure (1) the feasibility of recruiting a representative sample of young women aged 16 to 35 years living in Kanagawa Prefecture (population of 9,084,00012) using an SNS for a health study and (2) the knowledge and attitudes of that representative sample of young women toward CC prevention. The data were compared with the AUS study, where very comprehensive CC screening and human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine programs are established.13,14

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Recruitment

Inclusion criteria were being female; having an age of 16 to 35 years; living in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan; and a written consent for completing an online survey. As minors are legally defined as 19 years and younger in Japan, girls aged 16 to 19 years required written parental consent for participation in the study.

Participants were recruited for 9 months, from July 2, 2012, to March 20, 2013, using FB advertisements targeted by age and place of residence, in addition to a banner on the homepage (HP) (http://kanagawacc.jp/) to advertise our CC prevention project, which started in 2011 as the Yokohama-Kanagawa CC Prevention Project (YKCCPP).15 The YKCCPP was announced via public lectures, television, and brochures, whereas FB advertisements were displayed only for FB users whose profiles met the inclusion criteria. We chose the “cost-per-click” option for FB advertisements, which charged each time the advertisement was clicked on. When someone clicked on the advertisement, they were redirected to our secure study Web site that contains detailed study information. Potential participants expressed their interest by giving their name, residential and email addresses, age, and telephone number on a form on the study Web site. After receiving information from potential participants, a consent form was sent to their residential address by mail. All potential participants who furnished signed consent forms had their final eligibility confirmed by telephone or email; those who did not respond to a second notification by email within 2 months were considered to have withdrawn their expression of interest (EoI). Eligible participants were then emailed instructions for accessing the online survey. The online survey tool SurveyMonkey with the enhanced security option of Secure Socket Layers encryption was used to administer the survey to participants. For further protection of privacy, research assistants, who were not qualified to access the questionnaire data, provided each participant with a unique study ID to access the survey, so that the researchers could not connect a participant’s name with the unique ID. As compensation for participants’ time in the online survey, a gift card worth JPY 1,000 (US $1 = JPY 80 in June 2012) was sent to those completing it.

Questionnaire

The survey contained questions on demographic variables (date of birth, marital status, country of birth, educational background, and residential address); self-reported height and weight; how participants found the study; sexual history; and experience and knowledge of chlamydia, HPV, HPV vaccine, and CC. With the exception of several questions about CC, these questionnaires were almost identical to the study in Australia conducted in 2010 (AUS study).8,9

HPV and CC Knowledge Scores

The HPV and CC knowledge were evaluated using the same method as the AUS study.8,9 The HPV awareness was defined by a “yes” response to the question “Do you know what HPV is?”. The HPV knowledge was evaluated only among participants who responded “yes” to the question “Do you know what HPV is?”, using 6 subsequent “true/false/don’t know” questions. One point was given for each correct answer, and a knowledge scale (0–6, from no to high) was constructed. Participants who did not know what HPV was were automatically given a score of 0. The HPV knowledge scale was divided into 3 groups according to the participants’ scores: low (0–2), moderate (3–4), and high (5–6). The CC knowledge was also assessed using 7 “yes/no/don’t know” questions about the factors that reduce a person’s risk for CC. One point was given for each correct answer, and a knowledge scale (0–7) was constructed. The CC knowledge scale (0–7) was divided into 3 groups: low (0–2), moderate (3–4), and high (5–7).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 20 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY). We used Japanese Bureau of Statistics 2010 census data12 to compare our study group with the distribution of the general population. Regarding women’s educational background and body mass index (BMI), data from the Employment Status Survey 2012 from the Japanese Bureau of Statistics and National Health16 and the Nutrition Survey 2010 from Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare17 were cited, respectively. We compared demographic characteristics in our samples with those of the general population using Fisher exact test. Odds ratios, adjusted odds ratios, 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and 2-sided P values were estimated using binomial logistic regression analysis. In all analyses, we defined a 2-sided P < 0.05 as statistically significant. Data were treated as missing if no response was given or “don’t know” was selected. Binomial logistic regression analysis was used to identify independent predictors of HPV and CC knowledge.

Ethical Considerations

After users were directed to our secure study Web site, all subsequent study procedures took place outside the SNSs. This study protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committee of Yokohama City University School of Medicine.

RESULTS

Recruitment

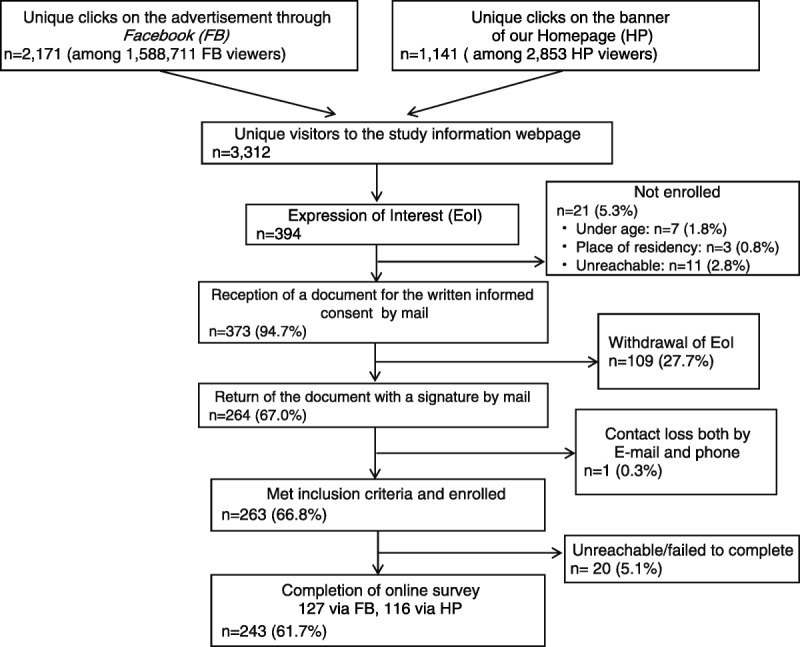

The FB advertisements were displayed 5,698,440 times from July 2012 until April 2013, resulting in 1,588,711 viewers and 2171 clicks on the advertisement that directed respondents to the study Web page. There were 2853 visitors to the YKCCPP HP, with 1141 visitors being directed to the study Web page. Of the total 3312 unique visitors to the study Web page, 394 (204 via FB, 190 via HP) showed an EoI in sending individual information from the Web page. We collected signed consents from 264 of those 394 women (67% of EoIs), and 243 (62% of EoIs) women completed the survey. Overall, 52% (127/243) were recruited through FB, and the remainder was recruited through the HP: the demographics were not different between the 2 groups except that the number of virgins was greater and the proportion of age of first sexual intercourse being 16 to 18 years was lower in the HP (data not shown). The detailed recruitment steps are shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Summary of recruitment steps. Sampling and response steps are shown. Percentages are calculated using the number of EoIs (n = 394). The EoI was defined to give their name, residential address, age, email address, and telephone number on a form on the study Web site.

Participants’ General Demographic Characteristics

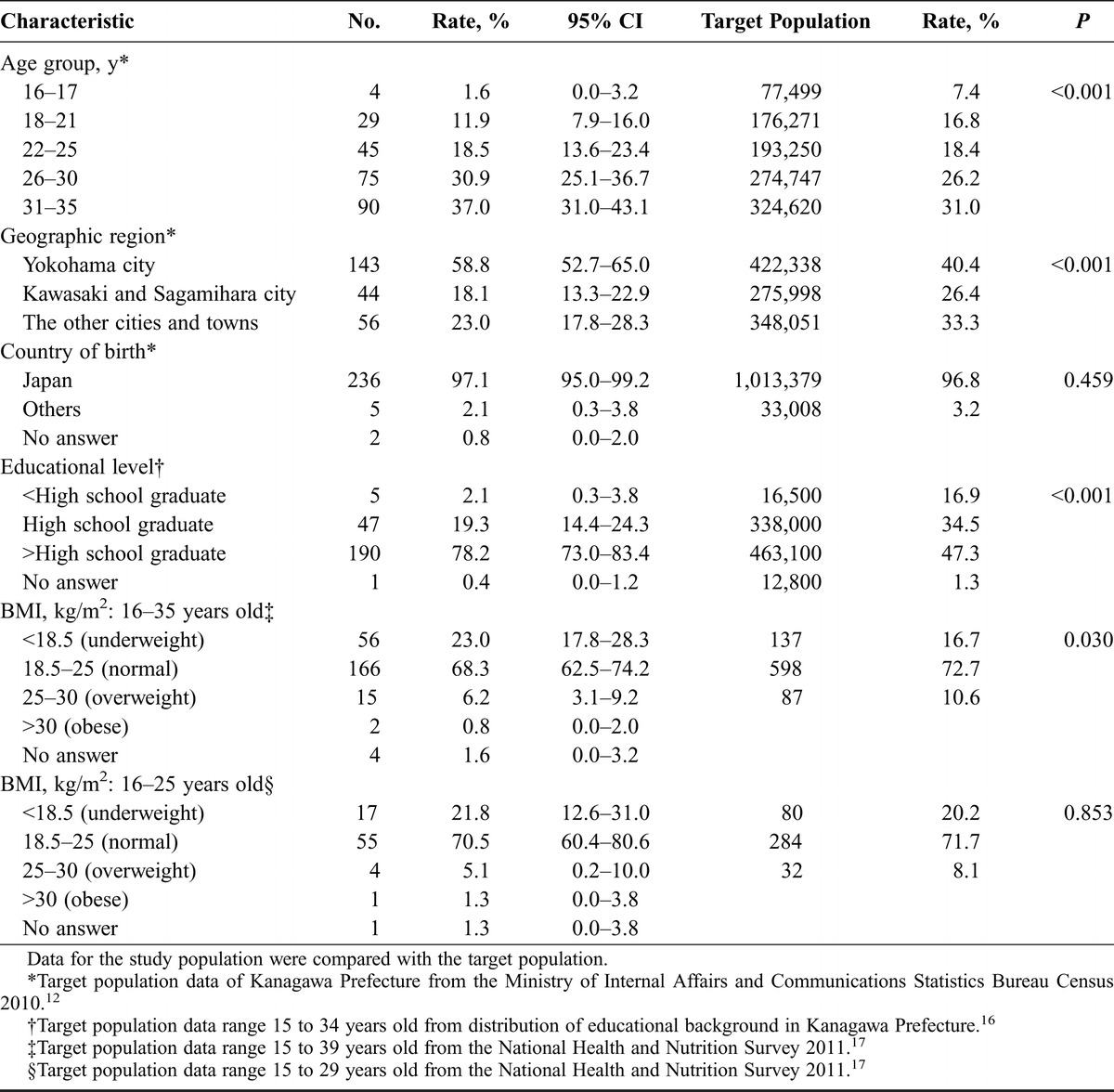

The participants’ general demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1. Compared with the general target population,12 participants aged 16 to 21 years were underrepresented, whereas those aged 22 to 25 years were representative, and those aged 26 to 35 years were overrepresented (P < 0.05).

TABLE 1.

General demographic characteristics of study participants

Residents in the capital (Yokohama City) were overrepresented compared with the other cities and towns (P < 0.05). Most participants were born in Japan (97.1%), which was similar to the target population (P = 0.46). As for educational background, 5 (2.1%) participants were high school students, 47 (19.3%) were high school graduates, and 190 (78.2%) had an educational level higher than high school graduate (P < 0.05). Another parameter of significant difference was that 23% of the study participants were underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2), compared with 16.7% of the women in the target population, according to the National Health and Nutrition survey17 (P < 0.05). However, for the participants aged 16 to 25 years, the BMI distribution was comparable with the target population (P = 0.85).

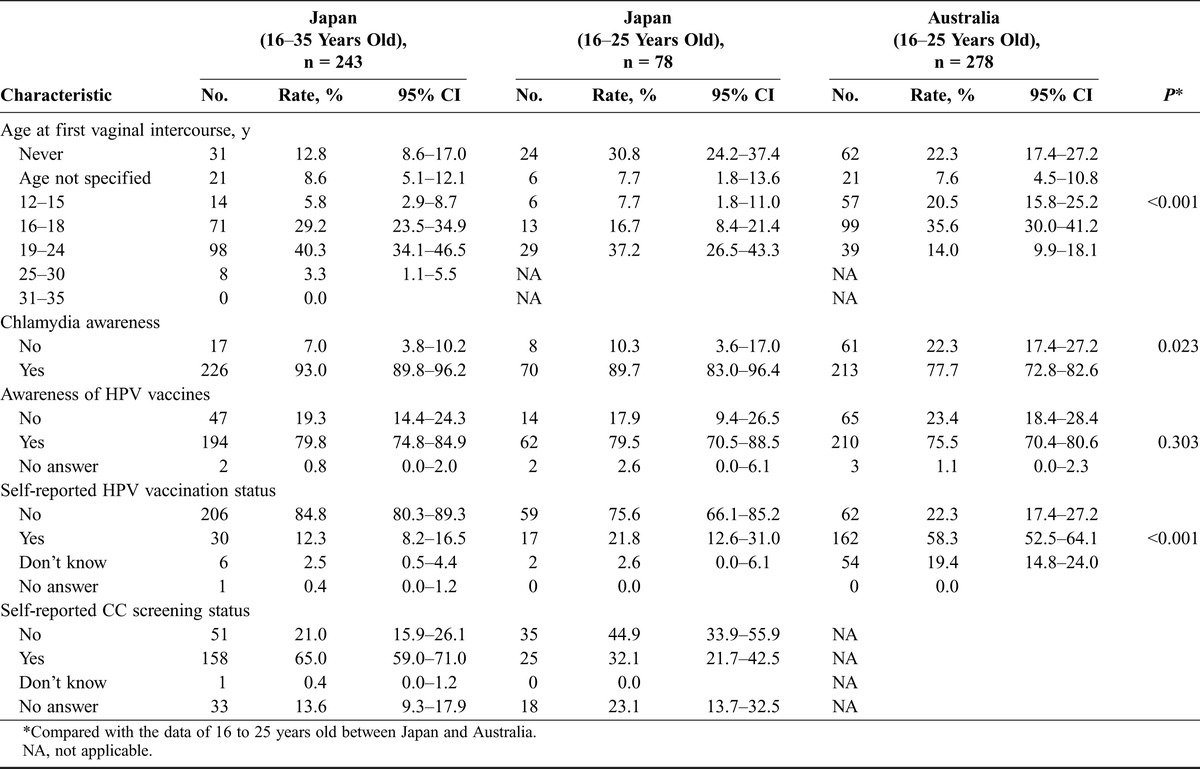

Critical Characteristics of Participants Related to CC Compared With the AUS Study

The analyses of critical characteristics of participants related to CC in the JPN study in comparison with data from the AUS study are shown in Table 2. The significant differences among participants aged 16 to 25 years were the age of first intercourse in 12 to 15 years old (JPN, 7.7% vs AUS, 20.5%; P < 0.001), chlamydia awareness (JPN, 89.7% vs AUS, 77.7%; P < 0.05), and self-reported HPV vaccination status (JPN, 21.8% vs AUS, 58.3%; P < 0.001). The rates of HPV awareness (JPN, 67.9% vs AUS, 62.2%; P = 0.895) and awareness of HPV vaccines (JPN, 79.8% vs AUS, 75.5%; P = 0.303) were comparable in the 2 studies. Self-reported CC screening status was asked only in the JPN study: 65.0% (158/243; 95% CI, 59.0–71.0) of participants aged 16 to 35 years whereas 32.1% (25/78; 95% CI, 21.7–42.5) of those aged 16 to 25 years reported having participated in CC screening at least once in their lifetime.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of critical characteristics of participants related to CC between JPN and AUS studies

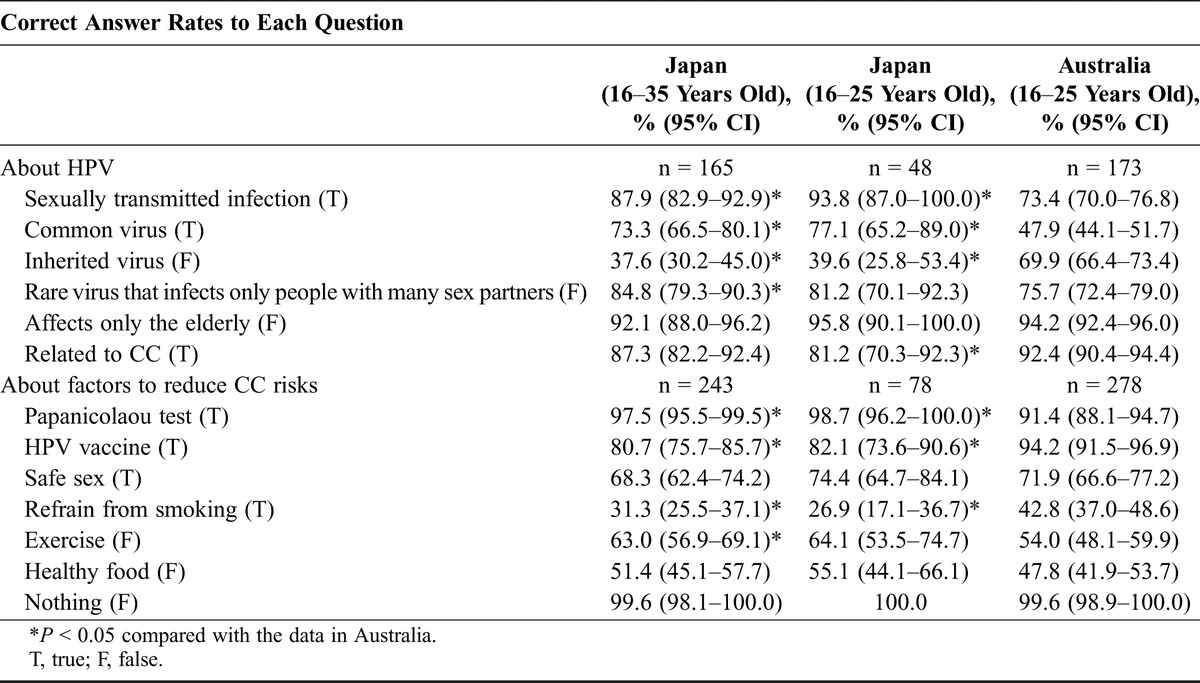

Comparison of HPV and CC Knowledge Between the JPN Study and the AUS Study

In the JPN study, HPV knowledge was assessed in the 164 participants who reported knowing what HPV was, whereas the questions about factors to reduce CC risks (CC knowledge) were asked to all participants. Percentages of correct answers to each item for HPV and CC knowledge were compared with data from the AUS study (Table 3). In both studies, almost all participants answered correctly “false” to the question that no factors reduce CC risks. Compared with the participants in the AUS study, those from Japan aged 16 to 25 years demonstrated better knowledge for HPV being a common virus and being sexually transmitted (P < 0.05). Among all JPN participants, 73.3% (95% CI, 66.5–80.1) recognized HPV as a common virus compared with 47.9% (95% CI, 44.1–51.7) for the AUS study. On the other hand, the correct answer of “no” regarding HPV as an inherited virus was obtained significantly less often in the JPN study (37.6%; 95% CI, 30.2–45.0) than in the AUS study (69.9%; 95% CI, 66.4–73.4). For the questions regarding reduction of CC risk, the correct answer rates of “true” for the Papanicolaou test were more than 90% in both studies; however, the answer rate of “true” regarding the HPV vaccine was significantly higher in the AUS study (94.2; 95% CI, 91.5–96.9) than in the JPN study (80.7%; 95% CI, 75.7–85.7). The correct answer rate of “true” for refraining from smoking was very low (31.3%; 95% CI, 25.5–37.1) in the JPN study and was significantly lower than the rate (42.8%; 95% CI, 37.0–48.6) in the AUS study.

TABLE 3.

Comparison between participants in Japan study and Australia study concerning their knowledge of HPV and CC

Although the mean (SD) HPV knowledge score among the JPN study participants aged 16 to 35 years at 3.1 (2.5) (95% CI, 2.8–3.5) was slightly higher than that among the AUS study participants aged 16 to 25 years (2.8 [2.4]; 95% CI, 2.5–3.1) (P = 0.03), it is noteworthy that there was no significant difference in the mean HPV knowledge scores for participants aged 16 to 25 years in both studies. The CC knowledge scores were comparable between the studies (JPN, 4.9 [1.0] and 95% CI, 4.8–5.0 vs AUS, 5.0 [1.0] and 95% CI, 4.9–5.1).

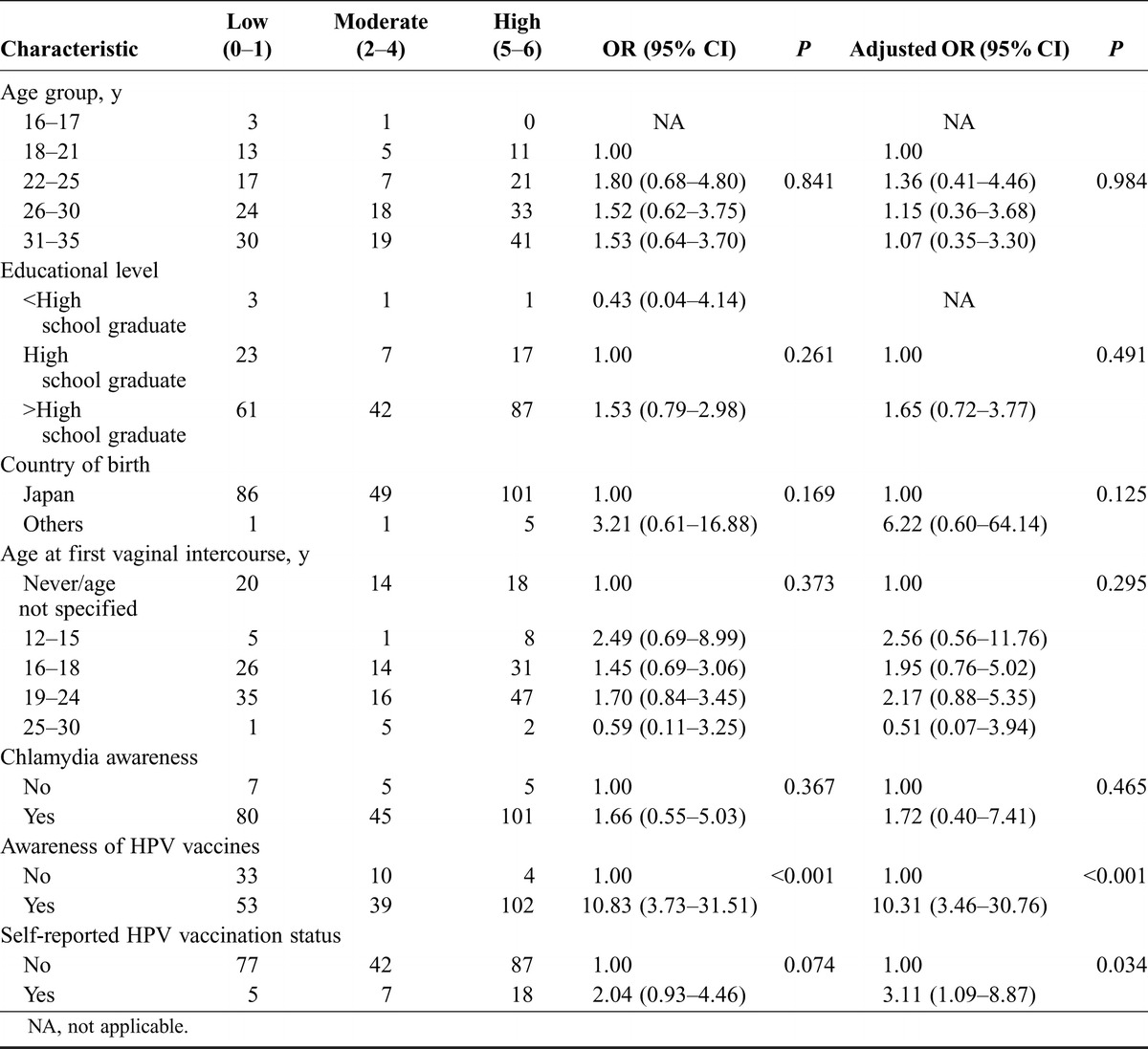

Predictors of High Knowledge Scores of HPV and CC Among Participants in the JPN Study

Table 4 shows predictors of high HPV knowledge. Awareness of HPV vaccine (adjusted odds ratio [OR], 10.31; 95% CI, 3.46–30.76; P < 0.001) and self-reported administration of HPV vaccination (adjusted OR, 3.11; 95% CI, 1.09–8.87; P = 0.034) were significant predictors of high HPV knowledge, with scores of 5 to 6 points. Whereas awareness of chlamydia was a significant predictor of a high HPV score (adjusted OR, 2.57; 95% CI, 1.11–5.94) in the AUS study,9 it was not significant in the JPN study (adjusted OR, 1.72; 95% CI, 0.40–7.41). There was no significant predictor related to high CC knowledge scores of 5 to 7 points found (Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/IGC/A226).

TABLE 4.

HPV knowledge of participants in Japan and ORs of high HPV knowledge compared with low/moderate HPV knowledge using univariate and multivariate analyses

DISCUSSION

In Australia and Japan, the recent age-adjusted CC incidences are 4.9 and 9.8, respectively, and the mortality rates of CC are 1.4 and 2.6, respectively, per 100,000 women.18 Australia has established a well-organized cervical screening program by conventional Papanicolaou test screening. The uptake is approximately 60% of the target population, and the program has succeeded in decreasing both the incidence and mortality rates of CC.18,19 In contrast, in Japan, the seriously low acceptance rate of the Papanicolaou test is thought to be the main reason for the increase in number of CC patients in Japan. The recommended CC screening guideline for JPN women is twice yearly for those 20 years and older.20 The self-reported coverage rate of the Papanicolaou test in the targeted women was only 32% in the survey of 2010.15 This is one of the lowest rates among developed countries.21 We recently reported that only 59.5% of young female workers or students in the Yokohama City University Hospital-based community who received catch-up HPV vaccinations (mean, 28; range, 21–48 years) had undergone CC screening in their lifetime.15 In the present study, Papanicolaou test uptake in the participants’ lifetime was 65%, which suggests that the participants of the present study had higher CC screening rates.

An HPV vaccine program in Australia began in 2007 and is ongoing for a target age of 12 to 13 years.13,14 In addition, a catch-up program was offered for women up to 26 years old through the end of 2009, and this achieved a high level of vaccination coverage.13,14 In Japan, only opportunistic HPV vaccination was available until a nationwide HPV vaccination program was widely initiated in 2011, mainly targeting girls aged 13 to 16 years. The nationwide HPV vaccination program was funded equally by the national government and by each regional government for either bivalent or quadrivalent HPV vaccines and finished in March 2013 achieving a high coverage rate (>70%).22 Subsequently, total coverage by the JPN government was endorsed and started in April 2013. However, its active approval has been suspended indefinitely since July 2013 to investigate mass media reports of a severe chronic pain syndrome.23 This potential adverse reaction has not been confirmed medically, nor has it been reported at such rates elsewhere in the world.24 However, in this current study, as most JPN study participants were older the target age for the national HPV vaccine program, the rate of self-reported HPV vaccination was low, at 21.8% in women aged 16 to 25 years, much lower than the rate of 58.3% in the AUS study. Such a difference between the JPN and AUS HPV vaccination programs for young women may enlarge the gap in CC status between Japan and Australia in the future.

Although more than half of the target women aged 16 to 35 years living in Kanagawa Prefecture were estimated to be FB users,11,25,26 we also placed an advertisement banner on the YKCCPP HP to boost subjects to be recruited. In this study, 52% were recruited by FB, whereas the remainder was recruited by HP, although the 2 groups did not differ significantly, except for sexual experiences. Even with study methods using an SNS, it was more difficult to recruit girls aged 16 to 17 years. In the AUS study, the study population of these ages was 14.0% in contrast to 19.8% of the target population.8 This tendency was greater in the JPN study with only 4 high school students (1.6%) participating in the study from among the 7.4% of the target population. The low participation rate among this age group in the JPN study was thought to be due to only approximately 30% of girls aged 16 to 17 years in the target population being FB users11,25,26 and due to the need for parental consent for participants younger than 20 years. This is in contrast to Australia in which it allows for professional assessment for mature minor status for those younger than 18 years to participate without parental consent. Another bias in the JPN study not seen in the AUS study8 was an uneven participation by geographic region. One explanation for the overrepresentation in Yokohama City is that our local CC prevention projects were well advertised by those living in Yokohama City. A limitation of our study, using SNS, is the bias that young participants had more awareness and knowledge about HPV and CC than the target populations as reported in the AUS study,8,9,27,28 although the latter study was performed 3 years earlier.8,9 Our data also showed that significantly more educated women than in the target population participated in the JPN study after adjusting for the age distribution, similar to the AUS study.8 Ideally, for the precise comparisons among countries, simultaneous study performance is required. However, in the JPN study, the participants were shown to have very high awareness and knowledge about HPV and CC that was comparable with the AUS study. The high profile of the HPV vaccine program by national and local governments in Japan might have influenced these results, in addition to the television commercial for CC screening advocacy broadcasted repeatedly after the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011. An important point for ongoing education was the lack of knowledge about the link between smoking and CC in the JPN study.

CONCLUSIONS

The SNSs are an efficient method to recruit young women into health surveys. A nationwide survey about CC prevention using SNSs would be a next step to better understand young women’s beliefs and potential barriers to better uptake of the JPN national HPV vaccine program.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Yeshe Fenner, Navera Ahmed, and Bharathy Gunasekaran for providing information and raw data for this study as well as Stefanie Hartley for calculating 95% CI for some of these AUS data to be compared with the Japanese data. They also thank Yukimi Uchiyama, Atsuko Koyama, Hideko Yamauchi, and Athena Costa for secretarial help and Chords Ltd. for the technical support.

Footnotes

Supported by 2012 and 2013 Grants-in-Aid from the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare of Japan.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citation appears in the printed text and is provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.ijgc.net).

REFERENCES

- 1. Matsuda A, Matsuda T, Shibata A, et al. Cancer incidence and incidence rates in Japan in 2007: a study of 21 population-based cancer registries for the Monitoring of Cancer Incidence in Japan (MCIJ) project. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2013; 43: 328– 336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hayashi Y, Shimizu Y, Netsu S, et al. High HPV vaccination uptake rates for adolescent girls after regional governmental funding in Shiki City, Japan. Vaccine. 2012; 30: 5547– 5550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Plummer M, Peto J, Franceschi S. International Collaboration of Epidemiological Studies of Cervical Cancer. Time since first sexual intercourse and the risk of cervical cancer. Int J Cancer. 2012; 130: 2638– 2644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Morton LM, Cahill J, Hartge P. Reporting participation in epidemiologic studies: a survey of practice. Am J Epidemiol. 2006; 163: 197– 203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Blumberg SJ, Luke JV. Reevaluating the need for concern regarding noncoverage bias in landline surveys. Am J Public Health. 2009; 99: 1806– 1810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Garrett SK, Thomas AP, Cicuttini F, et al. Community-based recruitment strategies for a longitudinal interventional study: the VECAT experience. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000; 53: 541– 548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Robinson JL, Fuerch JH, Winiewicz DD, et al. Cost effectiveness of recruitment methods in an obesity prevention trial for young children. Prev Med. 2007; 44: 499– 503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fenner Y, Garland SM, Moore EE, et al. Web-based recruiting for health research using a social networking site: an exploratory study. J Med Internet Res. 2012; 14: 1– 13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gunasekaran B, Jayasinghe Y, Fenner Y, et al. Knowledge of human papillomavirus and cervical cancer among young women recruited using a social networking site. Sex Transm Infect. 2013; 89: 327– 329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Telecommunication report from the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications in 2011 [Web site]. Available at: http://www.soumu.go.jp/johotsusintokei/whitepaper/eng/WP2011/chapter-3.pdf#page=1 Accessed March 9, 2014

- 11.Lifemedia, Inc. Research of Japanese Facebook users June 2013 [internal document]. Available at: http://research.lifemedia.jp/2013/06/130621_facebook.html Accessed March 9, 2014 (in Japanese).

- 12.Statistics Japan, Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Population data from census 2010 [Web site]. Available at: http://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/kokusei/index.htm Accessed January 26, 2014

- 13. Brotherton JM, Fridman M, May CL, et al. Early effect of the HPV vaccination programme on cervical abnormalities in Victoria, Australia: an ecological study. Lancet. 2011; 377: 2085– 2092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Garland SM, Skinner SR, Brotherton JM. Adolescent and young adult HPV vaccination in Australia: achievements and challenges. Prev Med. 2011; 53: S29– S35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Miyagi E, Sukegawa A, Motoki Y, et al. Attitudes toward cervical cancer screening among women receiving HPV vaccination in a university hospital-based community: interim two-year follow-up results. In: J Obstet Gynaecol Res, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Statistics Japan, Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Distribution of educational background in Kanagawa prefecture from employment status survey 2012 [Web site]. Available at: http://www.stat.go.jp/data/shugyou/2012/pdf/kgaiyou.pdf Accessed July 23, 2013 (in Japanese).

- 17.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. National Health and Nutrition Survey 2010 [Web site]. Available at: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/houdou/2r9852000002q1st.html Accessed July 2, 2013 (in Japanese).

- 18.National Cancer Institute, U.S. National Institutes of Health. International Cancer Screening Network. Age-adjusted cervical cancer incidence and mortality rates for 2008 for 32 countries, organized by Region of the World, participating in the ICSN [Web site]. Available at: http://appliedresearch.cancer.gov/icsn/cervical/mortality.html Accessed July 2, 2013

- 19.Australian Government, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Australian Cancer Incidence and Mortality (ACIM) books: authoritative information and statistics to promote better health and wellbeing [Web site]. Available at: http://www.aihw.gov.au/acim-books/ Accessed September 15, 2013

- 20.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Report from the National Screening Committee: Revision of the Programs for Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening based on the Law for the Health Law for the Aged. Tokyo, March 2004 (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 21.OECD Publishing. Screening, survival and mortality for cervical cancer. OECD (2011), in Health at a Glance 2011: OECD indicators [Web site]. Available at: http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/health-at-a-glance-2011_health_glance-2011-en Accessed May 26, 2013

- 22.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. An interim nationwide vaccine program, Japan. Available at: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/kenkou/kekkaku-kansenshou28/pdf/vaccine_kouhukin_enchou.pdf Accessed March 24, 2013 (in Japanese).

- 23.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Report from the deliberations on HPV vaccines at adverse reaction committee held on December 25, 2013. Available at: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/shingi/0000033881.html Accessed March 11, 2013 (in Japanese).

- 24.World Health Organization. GACVS Safety update on HPV Vaccines Geneva, 13 June 2013. Available at: http://www.who.int/vaccine_safety/committee/topics/hpv/130619HPV_VaccineGACVSstatement.pdf Accessed March 11, 2014

- 25.FB Japan. FB advertisement [Web site]. Available at: https://www.FB.com/advertising Accessed March 3, 2014

- 26.SocialBakers. FB Statistics by Country. Available at: http://www.socialbakers.com/FB-statistics/ Accessed March 3, 2013

- 27. Klug SJ, Hukelmann M, Blettner M. Knowledge about infection with human papillomavirus: a systematic review. Prev Med. 2008; 46: 87– 98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pitts MK, Heywood W, Ryall R, et al. Knowledge of human papillomavirus (HPV) and the HPV vaccine in a national sample of Australian men and women. Sex Health. 2010; 7: 299– 303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]