Abstract

Caribbean Latinos are the largest Latino group in Boston, primarily located in the Jamaica Plain (JP) neighborhood. There are various macro-level public health issues that result from the built environment in JP, factors which can create and sustain health disparities. Caribbean Latino youth are a priority group in JP, and it is important to address the causes of disparities early in life to promote good health. Presented here is an integrated research-and-action model to engage community stakeholders and researchers in designing an intervention to mitigate the negative health effects of the built environment and maximize community assets. The approach operates from a community empowerment model that allows public health practitioners, policy makers, researchers and residents to take an up-stream approach to improve health by focusing on the built environment, which is integral to community development.

Keywords: Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR), built environment, health, disparities, Caribbean Latinos

Introduction

There is a growing body of literature linking the built environment to disparities in chronic disease (Jackson, 2003; Northridge, Sclar, & Biswas, 2003). The increased prevalence of chronic conditions such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease and asthma has led researchers, policy-makers and practitioners to revisit the relationship between urban planning, community development and public health (Brisbon, Plumb, Brawer, & Paxman, 2005; Northridge et al., 2003). This is particularly true given that characteristics of the built environment can: (1) result in exposure to hazardous conditions or substances; and (2) shape lifestyles and influence health behaviors, both of which contribute to the development and progression of chronic disease (Perdue, Stone, & Gostin, 2003). As health risks due to the built environment can most effectively be mitigated through community-wide interventions, public health practitioners have turned to community development approaches designed to facilitate community participation and empowerment such as community organizing, coalition development and community building (Minkler, 2006).

Drawing upon community development strategies, presented here is an integrated research-and-action model designed to engage community stakeholders, public health officials and researchers in the development of an intervention with the goal of improving the health of Caribbean Latino youth in Boston, Massachusetts. Background literature is presented, followed by an illustrative case study describing the community process employed to narrow the research focus and design the actual intervention, which is also described.

Background

Community development refers to targeted local action aimed at improving community life (Petersen, 1994). Such strategies generally involve resource mobilization, the strengthening of community networks, coalition development, capacity building, and community resident engagement primarily through organizing and local outreach (Labonte, 1999). Working in collaboration with community residents, organizers work to change public and organizational policies that threaten the vitality of communities and proliferate inequity (Labonte, 1999). Although the original focus of community development was on social and economic empowerment and elements such as infrastructure, a focus on the social determinants of health for health improvement has brought community development approaches into the public health spotlight (Petersen, 1994). Given what is now known about the relationship between living environments, social environments and chronic disease, the inclusion of community development in public health research, practice and interventions is imperative to improve population health.

The core tenets of community development: participation, equity, collective action and empowerment, can now be found in some approaches to public health research like community-based participatory research (CBPR) (Petersen, 1994). CBPR, like community development, emphasizes participation, capacity building and empowerment. The focus is on achieving community relevant strategies to address underlying social, political and economic inequities that influence health behavior and over time health outcomes (Minkler, Vasquez, Chang, & Miller, 2008; Minkler & Wallerstein, 2003; Wallerstein & Duran, 2006).

Integral to CBPR is the research process, how partners come together to collectively identify community concerns and develop intervention strategies, and what strategies are used to facilitate participation, the enhancement of relationships, capacity building and empowerment. Because CBPR is asset-based and underscores the importance of building on existing community knowledge, partners are encouraged to contribute to the process and share experiences and knowledge (Minkler & Wallerstein, 2003). Here, the partnership itself can act as a catalyst for change, as residents, community leaders and researchers take collective action towards a shared vision and mutually established goals (Fawcet et al., 1995). In sum, the goals of both community development work and CBPR include empowering residents so they may act to advance positive social change at the community level. By including residents and community stakeholders in the decision-making process these strategies build community capacity for self determination and leadership, through the development of new relationships and the provision of skills necessary to achieve community goals.

CBPR, because it is focused on empowerment and participation, has been identified as a promising approach to developing interventions to tackle health disparities. Its incorporation of community development strategies allows for the design of health interventions that are community relevant and culturally appropriate, tailored to the values, experiences, practices and worldview of community members (Wallerstein & Duran, 2006). This is critical as racial and ethnic disparities in health have been well documented yet poorly addressed (AHRQ, 2007). A complex set of interrelated social, political, economic, and environmental factors are responsible for the proliferation of health disparities, and the factors that create and sustain disparities vary across communities among racial/ethnic, cultural, and linguistic minority groups. It is therefore necessary to engage in research that may, by design and intention, lead to evidence-based interventions to address disparities, especially in underserved immigrant and minority communities. Using CBPR, researcher content area expertise is contextualized by community knowledge; leading to the development of effective health interventions that address community health concerns. Simultaneously, community mobilization and empowerment has the power to spark local policy change to address distal factors that sustain disparities, such as inadequate education and lack of economic opportunity.

Health disparities and Caribbean Latinos

Caribbean Latinos, predominantly from Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic, are the largest Latino group in Boston, primarily located in the Jamaica Plain (JP) neighborhood. As a population, Caribbean Latinos on the United States mainland bear a disproportionate burden of chronic disease. Studies on older Caribbean Latino adults (over 40 years of age) in Massachusetts have identified disparities such as depression, diabetes, and obesity (Bermudez & Tucker, 2001). While less is known about children and youth, available evidence suggests that Caribbean Latino children and youth suffer an unequal burden of asthma, obesity, and diabetes compared to their Mexican and non-Latino white counterparts.

Puerto Rican children are disproportionately impacted by asthma (Lara, Akinbami, Flores, & Morgenstern, 2006). A study by Lara et al. has found that Puerto Rican children have both a higher prevalence of lifetime reported asthma diagnosis (26%) and recent attacks (12%) than Black (16% and 7%), non-Latino white (13% and 6%), and Mexican children (10% and 4%) (Lara et al., 2006). Another study of families in New York City found that among Caribbean Latino households, Puerto Ricans had the highest asthma prevalence among Latino ethnic groups (Ledogar, Penchaszadeh, Garden, & Iglesias, 2000).

Obesity is a risk factor for chronic diseases such as diabetes, heart disease, and asthma, consequently, disparities in obesity may lead to disparities in other chronic diseases. Latino students in Boston are more than twice as likely to be overweight or obese compared to non-Latino white students. In addition, 48.1% of Latino school students versus 63.2% of non-Latino white students engage in the recommended amount of physical activity weekly (BPHC, 2008). While local data is not available by ethnic sub-groups, as Caribbean Latinos make-up the majority of the state’s Latino population it is likely that Caribbean Latinos have a similar risk profile for obesity as the general Latino population (Census, 2007).

The prevalence of type-2 diabetes is rare in youth but has increased over the last decade, attributable to a greater prevalence of obesity and decreases in physical activity. Minority youth are disproportionately impacted by diabetes (Rosenbloom, Joe, Young, & Winter, 1999). Although type-2 diabetes disproportionately impacts Latinos, studies to date have focused mainly on Mexican Americans, and little is known about Latino sub-populations such as Caribbean Latinos. The elevated prevalence of type-2 diabetes in Caribbean Latino adults as well as the low rates of physical activity and high rates of obesity among Caribbean Latino children suggest that Caribbean Latino youth are at high risk of developing type-2 diabetes (Rosenbloom et al., 1999). By addressing the causes of health disparities among Caribbean Latino youth early in life, it is possible to provide children with living environments and social conditions conducive to good health, which can create pathways to health as opposed to disparities.

Health and the built environment

While the field of public health has historically focused on the impact of environmental exposures on health, the conception of the environment has matured from a narrow focus on sanitation to a broader understanding of the role that man-made systems and structures play in the health and wellbeing of communities (Srinivasan, OFallon, & Dearry, 2003). More specifically, public health practitioners and policy makers have begun to address how the built environment may serve to exacerbate, and/or protect against health disparities. This has particular importance for racial and ethnic minorities, including new immigrant communities. As these populations are overrepresented in poverty and often lack political power or influence, they are disproportionately exposed to the deleterious effects of the built environment, and consequently face an increase in disease-related morbidity and mortality (Schulz & Northridge, 2004).

The built environment refers to all human-modified structures and places such as homes, schools, workplaces, parks, industrial areas, farms, roads and highways (Dearry, 2004; Srinivasan et al., 2003). Although the elements that comprise the built environment are varied, three primary methods by which environmental factors can impact health are through housing, transportation, and the characteristics of neighborhoods and communities (Srinivasan et al., 2003). Regarding housing, the impact of housing conditions on health has been well documented (Bashir, 2002). Although there are multiple pathways by which housing influences health, exposure to household environmental risks including allergens, mold, lead, and pests has been associated with the development of a wide range of illnesses including asthma, respiratory infections, and cardiovascular disease (Bashir, 2002). Similarly, transportation related factors, such as trafic congestion, availability of public transportation, and transportation policies and regulations have been linked to negative health outcomes. For example, air pollution due to motor vehicle emissions (influenced by factors including trafic congestion and emissions policies), has been associated with respiratory and cardiovascular morbidity (Brugge, Durant, & Rioux, 2007). Furthermore, the lack of appropriate or accessible transportation may impede access to health-related services such as healthcare, exercise facilities, supermarkets, and recreational spaces.

With the recent focus on obesity, neighborhood characteristics including walk ability and the availability of green spaces such as parks and playgrounds have been the focus of public health practitioners and policy makers. Physical inactivity has been associated with an increased risk of several health conditions including diabetes, hypertension, colon cancer, and coronary heart disease. Neighborhoods can both inhibit and promote physical activity (Susan, Marlon, Reid, & Richard, 2002), and influence how residents respond to and recuperate from adverse health events (Clarke & George, 2005). Finally, neighborhood characteristics can influence levels of social capital and social cohesion, both associated with health (Leyden, 2003).

However, Schulz and Northridge note that the built environment is only one link in a chain of social, political, and historical forces that serve to act on health and health disparities. These “social determinants of health” provide the context through which the built environment is experienced and may serve to modify the influence of environmental entities on health. For example, a neighborhood may have safe, walkable, and easily accessible green spaces and recreation areas; however some residents may not feel comfortable making use of these resources due to historical patterns of segregation. In such a case, while the physical resource is present, social and cultural forces may limit its availability to certain populations and work to further disparities (Schulz & Northridge, 2004).

Case study: Nuestro Futuro Saludable

In order to address the impact of the built environment and to begin to address health disparities among Caribbean Latinos in Boston, the CBPR partnership Nuestro Futuro Saludable: the JP Partnership for Healthy Caribbean Latino Youth was established. University researchers, public health officials, healthcare providers, community stakeholders and residents formed a CBPR partnership to develop, implement, evaluate and disseminate an intervention to address health disparities impacting residents in the Jamaica Plain (JP) neighborhood of Boston, Massachu-setts. The section that follows describes this partnership as well as the community participatory process employed to develop an intervention designed to: (1) increase youth knowledge of adequate nutrition and physical activity, as well as their awareness of the social determinants of health; and (2) enhance their perception of their ability to affect change in their community and thus reduce stress.

Like many urban centers, JP is experiencing gentrification and population shifts. According to the JP Neighborhood Development Corporation (JPNDC), 30 years ago the JP neighborhood was considered too risky for a mortgage. Today however, JP is the third most expensive Boston neighborhood. It is a racially/ethnically and culturally diverse community with a vibrant history of immigration that is home to nearly 29,500 residents; 29% of JP’s population is Latino, of predominantly Caribbean origin (BPHC, 2008). One third of Jamaica Plain residents are between the ages of 0 and 24, and 30% of all school children in JP report speaking Spanish at home (BPHC, 2008). Overall, poverty in JP is slightly lower than overall poverty in Boston (17% and 20% respectively), although the number of children living below the poverty line in JP is higher than the number of children living below poverty in Boston, overall (28% and 26%, respectively) (BPHC, 2008). Unlike many urban areas, JP is rich in planned green spaces, including parks, playgrounds and trails. Despite the available resources, only 56% of Latino high school students in JP report getting adequate physical activity (BPHC, 2008).

For Caribbean Latinos, the conditions that lead to health disparities have been exacerbated in JP as a result of gentrification. Similar to other cities in recent decades, Boston has seen a reverse of “white flight” or the large-scale movement of whites and affluent minorities from cities to the surrounding suburbs and exurbs, a phenomenon that emerged after World War II but was particularly rampant during the period after the civil rights era through the 1980s. This process led to segregation, as cities such as Boston became primarily low-income minority areas surrounded by more affluent white suburbs. In Boston, the departure of more affluent residents led to a decrease in property values and lower tax revenues, which combined with red-lining, zoning policies and an economy in recession, ushered the city into a prolonged period of urban decay. Consequently, white-flight led to thriving suburbs and exurbs while cities suffered as they were plagued by crime, violence, unemployment, high rates of poverty and homelessness (Lamb, 2005; Smith, 1996).

The revived economy of the 1990s sparked a period of urban renewal and placed new focus on deteriorating and blighted urban areas. Increased revenues and the creation of Empowerment and Enterprise Zones created an array of community and economic development initiatives as a solution for chronic divestment. This resulted in improvements in the quality of life, as once decrepit urban areas slowly recovered and began to rebound. In the short-term, this led to an increase in jobs, better infrastructure, parks and outdoor spaces, as well as improvements in the health and human services and supports available to minority residents. In the long-term, however, this has also led to a dramatic change in the make-up of city neighborhoods. The proximity to city financial and business centers, and the health and cultural resources, strong infrastructure and good public transportation within cities made living in them much more attractive. This combination of factors has led to a reverse movement of people, primarily affluent whites, from the suburbs back to the cities, which consequently led to the gentrification of urban neighborhoods, producing changes evident at the neighborhood or census tract levels (Clay, 1979).

The process of gentrification in JP has resulted in transformations in environmental conditions and the social context specifically caused by macro-social factors and inequalities. Community partners report there are “2 JPs,” one affluent with residents who can afford the $498,000 median home price, as well as the high end shops, and the other a community with an average family income of $11,000 per year. Such inequities increase stress as well as changes in social integration and support, which can negatively impact health behaviors, resulting in negative health outcomes and an overall poorer level of general socio-emotional and physical wellbeing.

A research-and-action model to empower local communities

In order to mitigate the deleterious effects of the built environment in JP, a CBPR approach to intervention research was designed and implemented with support from the National Centers for Minority Health and Health Disparities (NCMHD). The overall goals of this two-year research project were to develop, implement, evaluate and disseminate a community specific and culturally appropriate intervention to address health disparities among Caribbean Latinos in JP. The disease specific focus of the intervention was not pre-identified by researchers, but was instead to be identified by the community as part of the CBPR process, thus giving ownership and decision-making power to the population that would be impacted by the work. The CBPR approach employed involved a Steering Committee (SC) that consisted of university researchers and directors from local community organizations and a Community Advisory Board (CAB) which included local residents, youth and front line service providers and advocates.

The model was designed so that the work of the SC in designing the intervention would be contextualized by the guidance and decision-making of the CAB. SC and CAB members developed a memorandum of understanding outlining their roles and responsibilities, as well as the duration of their term. The collaborative development for the document assured a common language, understanding and commitment from all parties. The SC was responsible for providing the CAB with community-level data to complement CAB members’ intimate knowledge of community needs and issues, allowing CAB membership to integrate data provided by community partners with knowledge learned through personal and professional experience in the community. Similarly the CAB increased the SC’s awareness of health disparities as they were experienced in the community, and the SC increased the CABs knowledge of research design and the principles of CBPR. Accurate, timely, and ongoing open communication and coordination between the SC and the CAB are essential to the success of this project, as such, all meetings, whether SC or CAB, are open to any and all members of the SC and CAB. To increase transparency, all project materials and associated documents are posted on a secure site which members of both the SC and CAB can access. The organizational structure, with the interlocking membership of the SC and the CAB, was designed to ensure: (1) SC accountability to the community; and (2) that the recommendations of the CAB were based on the needs of the community.

Given the complexity of the factors that contribute to and sustain disparities, the SC reflected a broad range of disciplines. University investigators represent diverse disciplinary backgrounds spanning university schools and departments. Community investigators represent local policy makers, non-profit organizations, health and human services, healthcare, advocacy, and local governmental sectors. The diversity of the SC thus brings expertise in public health, occupational health, epidemiology, nutrition, social work, education, urban planning, medicine, and policy, in addition to CBPR experience. The multitude of perspectives at the table allows the SC to examine health disparities and community level factors through multiple lenses, enriching design and appropriateness of the intervention. In addition, having local policy makers and multiple community sectors involved in the process facilitates the creation of sustainable change through policy advocacy and local grassroots action.

Establishing the CAB

The first aim of the SC was to convene a representative CAB. This process included recruiting CAB members, building a rapport and sense of mission among the CAB, establishing a leadership structure, and ensuring coordination between the CAB and the Steering Committee (SC). Because this work is focused on Caribbean Latino youth, the SC determined that the CAB should be primarily individuals of Dominican and Puerto Rican origin who live or work in JP. In addition, it was important for the SC that youth be sufficiently represented on the CAB. Although it was not a criterion that CAB members should be engaged in community development work, all members of the CAB are involved in grassroots organizing activities, advocacy and outreach efforts related to the social determinants of health, and/or neighborhood economic development initiatives. This has been a good fit for the intervention research as it marries community organizing and leadership expertise with the health sciences. In addition, it highlights how CBPR is a community development approach where participation, capacity building and empowerment facilitate advocacy, action and leadership for health improvement and community wellbeing. The CAB includes four university; three youth service workers including a health educator, provider and organizer; four local youth between the ages of 16 and 24; and two local parents. CAB members were recruited in collaboration with the CAB-SC liaison, who facilitates a health equity movement in JP, centered around youth employment.

Within the first two CAB meetings, members determined roles and responsibilities as well as established a leadership structure, which employs a rotating chairperson, allowing multiple members to take on leadership roles. Communication between CAB members and the Steering Committee has been ongoing with members of the Steering Committee present at every CAB meeting. Additionally, all project materials are stored on a secure website accessible to Steering Committee and CAB members in order to facilitate communication.

The CAB meets in Jamaica Plain in order to provide familiar surroundings to CAB members. Beyond CAB meetings, CAB sub-committees have been convened as needed to discuss intervention logistics. To date, the benefits of this partnership include enhanced relationships between researchers and community members and co-learning. Thus far, the CAB has participated in several capacity-building activities such as learning principles of academic research and CBPR, as well as learning the elements of intervention design. In addition, researchers have provided consultation to community partners on grant development.

To encourage positive relationships between the CAB and Steering Committee, we employed several communication strategies including a continual feedback system utilizing “question mark” index cards which allow CAB or SC members to request additional clarity about unfamiliar research, community, or cultural concepts and/or language. We also developed a project “glossary” for the CAB to clarify research and academic terminology, and have incorporated both active and passive team building activities into our meetings. Finally, both the social networks of the Community Advisory Board and Steering Committee have been expanded through this collaboration as members of both groups have increased ties to the other’s respective communities.

Determining a research focus

The determination of a condition-specific focus was an essential function of the CAB. Several activities were conducted in order to select a disease condition upon which to focus. Prior to convening the CAB, local level disease-specific data collected by the Massachusetts Department of Public Health and Boston Community Health Centers was reviewed. Secondary data related to the social determinants of health in JP collected by the Jamaica Plain Youth Equity Collaborative was also analyzed. This data was collected through focus groups and anonymous key informant interviews with JP youth. After reviewing and analyzing existing data, additional key informant interviews with local youth, parents, providers and activists were conducted to determine community priorities and assets, as well as elements of the built environment -both social and structural- that are perceived to threaten health. In addition, factors and conditions that both facilitate and/or impede sustainable programming in the community were explored. Interviews were conducted until saturation was achieved.

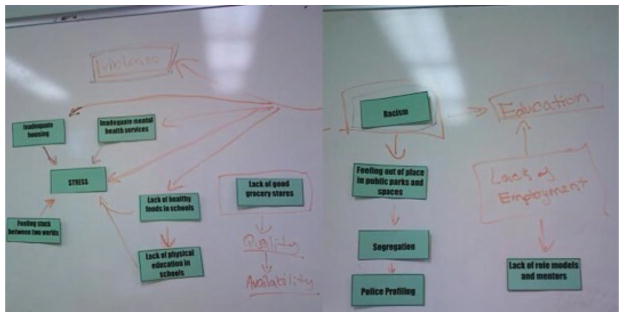

Interview data were coded into themes such as housing, educational inequity, racism and violence. Themes were presented to the CAB, which was asked to contextualize the data and identify the relationships and patterns between identified themes. Key themes contributing to health disparities, including but not limited to racism, segregation, stress, poor education, cultural isolation and access to quality housing and food can be seen on the board in Figure 1. CAB members were asked to draw arrows between these themes so that researchers could identify their perceived directionality of the relationship between community level factors that contribute to health disparities in JP.

Figure 1.

Factors that contribute to disparities in JP.

The CAB identified chronic and acute stress associated with racism and inequity as an important precursor to chronic disease and conditions. The CAB further identified components of the built environment and the social context by which it is surrounded, specifically inequity and racism, serving to exacerbate chronic and acute stress among youth in JP. Using these focus areas, the steering committee researchers began planning the intervention design.

Designing the intervention

In order to further ground the intervention in community concerns and priorities, CAB members were integral to the process of intervention design. Based on the identified areas of interest, CAB members were provided with sample interventions from the literature. They were then given brief training related to key components of intervention research and design. Next, CAB members in small groups were asked to generate the key elements of an intervention to address the priority area they felt should be a key starting place for the research, utilizing examples provided to them in combination with their own community expertise. Each group was provided with an intervention work sheet, and to ensure the ideas originated from the community, members of the CAB representing academia served as facilitators rather than participants during these discussions. This activity not only provided community specific information needed to develop the intervention; it also gave community representatives a basic understanding of the elements of intervention design and development. Furthermore, this activity demonstrated that in order to effectively design a research intervention the focus needed to be specific.

After a group discussion of each of the interventions, key themes which were present across the interventions were unpacked by researchers. Using these themes and the literature hypotheses, sample interventions were developed and presented to the steering committee for feedback. Once finalized, the interventions and hypotheses were presented back to the CAB for further comment and discussion. Through this process, the CAB decided that the aspect of the built environment that most affected Caribbean Latino youth was the educational system and decided that the final intervention should be school-based. Thus, meetings were held with local school personnel and an educator from the local middle school was appointed to the CAB. Through conversations with school administrators and staff, the intervention design was further refined to better fit the needs of the school population.

The intervention

The intervention developed utilizes a framework that incorporates information related to individual level health and health behavior, while promoting awareness of salient community and societal level factors that determine individual health and health behavior in order to encourage youth to incorporate health promoting behaviors into their daily lives to reduce stress. Specifically, the intervention will: (1) increase awareness of the relationship between physical activity, nutrition, living environments and health; and (2) provide concrete strategies for overcoming barriers to physical activity and nutrition, through the identification of environmental and individual assets. Civic engagement will also play a strong role in this intervention by enhancing Latino adolescents’ sense of empowerment and the perception of their ability to make positive change in their communities and in their lives. This increase in community connections may also directly influence chronic stress and reduce the physiological impact of chronic stressors.

The intervention developed through this process is unique for several reasons. First, while a multitude of interventions have attempted to modify dietary practices and increase physical activity to impact chronic disease outcomes such as obesity or diabetes, few have attempted to do so to decrease chronic stress. Even fewer studies have targeted the urban Latino immigrant population for their interventions, and virtually none have incorporated a socio-ecological intervention targeting both individual-level knowledge and attitudes while also incorporating the greater social determinants of health such as racism, discrimination and their influence on living environments.

Through this intervention youth will not simply gain an understanding of behavioral factors such as nutrition and physical activity that influence stress, they will learn about the ways in which the built environment produces health behavior, as well as how the social context surrounding the built environment creates and sustains inequitable living environments. The intervention will consist of a 10-week after school curriculum. Youth participating in the intervention will partake in activities such as mapping the neighborhood, including its history, green spaces, major food venues, liabilities and assets. The intervention seeks to provide experiences for early adolescents that instill a sense of agency over health behavior, empowering them to both identify community assets and employ strategies to mitigate the deleterious effects of the built environment that produce and sustain health disparities in JP.

Conclusions

Beyond leading to the development of an intervention that is community specific, working in collaboration with community stakeholders to determine and design this intervention has benefited the researchers and community partners alike. The literature describes mutual benefits to engaging in CBPR; here community partners were empowered to assume a leadership role in the development of research efforts aimed at improving health and the living environment in their community. This collaboration increased resident and frontline staff participation in the research process. Furthermore, the process by which this intervention research was undertaken has strengthened existing relationships between investigators and the greater JP community. The model has developed capacity through both knowledge acquisition and the expansion of personal social networks. Community members have gained knowledge specific to research partnerships for health, conducting community needs assessments, intervention research planning and design, the social determinants of health, analyzing and interpreting data. Simultaneously, investigators have gained knowledge related to the dynamics of community and community infrastructure, how the JP youth community is experiencing health disparities and the factors that create and sustain them, as well as how to negotiate diverse community perspectives and approaches for creating sustainable interventions that reflect community needs. All have expanded their social networks through the development of relationships with diverse community, organizational and institutional stakeholders.

Addressing the deleterious effects of the built environment requires collective action and community empowerment. Characteristics of the built environment can shape lifestyles and influence health behaviors, which can contribute to the development and progression of chronic disease. Community development approaches, such as CBPR provide a forum for researchers to unite with local communities and public health officials to stategically identify best practices, and collaboratively develop culturally appropriate and community specific interventions to tackle health disparities. In addition, by encouraging participation, building community capacity for leadership, promoting self determination, and empowering individuals to make change, CBPR can lead to the development of public health interventions that are community specific and culturally appropriate while simultaneously increasing both researcher and community capacity by creating space for co-learning.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by funding from National Institutes for Health, National Centers for Minority Health and Health Disparities (Grant #1-R24-MD-005095-01). Many thanks to our partners at the Center for Community Health Education Research and Service, the Latino Health Institute, the Center for Social Justice at the Boston Public Health Commission, the Southern Jamaica Plain Community Health Center, the Hyde Square Task Force, and the Mary Curley Middle School. In addition, we would like to thank the individual members of the Community Advisory Board for their leadership, motivation, and commitment collaboration to create change. Finally, we would also like to acknowledge our mentors and co-investigators on this project, Dr Doug Brugge, Dr David Gute, Mr Elmer Freeman and Dr Katherine Tucker for their support, mentorship and belief in this approach to intervention research.

References

- AHRQ. National Healthcare Disparities Report (No AHRQ Publication No 08-0041) Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bashir S. Home is where the harm is: Inadequate housing as a public health crisis. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(5):733. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.5.733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermudez OI, Tucker KL. Total and central obesity among elderly Hispanics and the association with type 2 diabetes. Obesity. 2001;9(8):443–451. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BPHC. The health of Boston 2008. Boston: Boston Public Health Commission: Research Office; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Brisbon N, Plumb J, Brawer R, Paxman D. The asthma and obesity epidemics: The role played by the built environment-a public health perspective. Journal of Allergy & Clinical Immunology. 2005;115(5):1024–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugge D, Durant J, Rioux C. Near-highway pollutants in motor vehicle exhaust: A review of epidemiologic evidence of cardiac and pulmonary health risks. Environmental Health. 2007;6(1):23. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-6-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Census. 2005–2007 American Community Survey 3-year Estimates. 2007 Retrieved May 6, 2009, from US Census Bureau http://www.census.gov.

- Clarke P, George L. The role of the built environment in the disablement process. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(11):1933–1939. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.054494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clay PL. Neighborhood renewal. Lexington, KY: Lexington Books; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Dearry A. Editorial: Impacts of our built environment on public health. Environmental health perspectives. 2004;112(11):A600. doi: 10.1289/ehp.112-a600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawcet S, Paine-Andrews A, Francisco V, Schultz J, Richter K, Lewis K, et al. Using empowerment theory in collaboartive partnerships for community health. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1995;23(5):677–697. doi: 10.1007/BF02506987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson RJ. The Impact of the built environment on health: An emerging field. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(9):1382–1384. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.9.1382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labonte R. Social capital and communty development: Practitioner emptor. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 1999;23(4):430–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.1999.tb01289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb CM. Housing segregation in suburban america since 1960: Presidential and judicial politics. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lara M, Akinbami L, Flores G, Morgenstern H. Heterogeneity of childhood asthma among Hispanic children: Puerto Rican children bear a disproportionate burden. Pediatrics. 2006;117(1):43–53. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledogar RJ, Penchaszadeh A, Garden CC, Iglesias G. Asthma and Latino cultures: Di3erent prevalence reported among groups sharing the same environment. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90(6):929–935. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.6.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyden KM. Social capital and the built environment: The importance of walkable neighborhoods. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(9):1546–1551. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.9.1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, editor. Community organizing and community building for health. 2. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, Vasquez VB, Chang C, Miller J. Promoting healthy public policy through community-based participatory research: Ten case studies. University of California; Berkeley: School of Public Health and Policy Link; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Northridge ME, Sclar ED, Biswas P. Sorting out the connections between the built environment and health: A conceptual framework for navigating pathways and planning healthy. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2003;80(4):556–568. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdue WC, Stone LA, Gostin LO. The built environment and its relationship to the public’s health: The legal framework. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(9):1390–1394. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.9.1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen A. Community development in health promotion: Empowerment or regulation. Australian Journal of Public Health. 1994;18(2):213–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.1994.tb00230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbloom AL, Joe JR, Young RS, Winter WE. Emerging epidemic of type 2 diabetes in youth. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(2):345–354. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.2.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz A, Northridge ME. Social determinants of health: Implications for environmental health promotion. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31:455–471. doi: 10.1177/1090198104265598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith N. The new urban frontier: Gentrification and the revanchist city. New York: Routledge; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan S, O’Fallon L, Dearry A. Creating healthy communities, healthy homes, healthy people: Initiating a research agenda on the built environment and public health. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(9):1446. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.9.1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susan LH, Marlon GB, Reid E, Richard EK. How the built environment a3ects physical activity: Views from urban planning. American journal of preventive medicine. 2002;23(2):64–73. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00475-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein NB, Duran B. Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promot Pract. 2006;7(3):312–323. doi: 10.1177/1524839906289376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]