Abstract

Background

Previous research indicates that individual differences in traits such as impulsivity, avidity for sweets, and novelty reactivity are predictors of several aspects of drug addiction. Specifically, rats that rank high on these behavioral measures are more likely than their low drug-seeking counterparts to exhibit several characteristics of drug-seeking behavior. In contrast, initial work suggests that the low drug-seeking animals are more reactive to negative events (e.g., punishment and anxiogenic stimuli). The goal of this study was to compare high and low impulsive rats on reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior elicited by cocaine (COC) and by negative stimuli such as the stress-inducing agent yohimbine (YOH) or a high dose of caffeine (CAFF). An additional goal was to determine whether treatment with allopregnanolone (ALLO) would reduce reinstatement (or relapse) of cocaine-seeking behavior under these priming conditions.

Methods

Female rats were selected as high (HiI) or low (LoI) impulsive using a delay-discounting task. After selection, they were allowed to self-administer cocaine for 12 days. Cocaine was then replaced with saline, and rats extinguished lever responding over 16 days. Subsequently, rats were pretreated with either vehicle control or ALLO, and cocaine seeking was reinstated by injections of COC, CAFF, or YOH.

Results

While there were no phenotype differences in maintenance and extinction of cocaine self-administration or reinstatement under control treatment conditions, ALLO attenuated COC- and CAFF-primed reinstatement in LoI but not HiI rats.

Conclusions

Overall, the present findings suggest that individual differences in impulsive behavior may influence efficacy of interventions aimed to reduce drug-seeking behavior.

Keywords: allopregnanolone, caffeine, cocaine, delay discounting, impulsivity, reinstatement, self-administration, stress, yohimbine

1. Introduction

Vulnerability to drug addiction and relapse to drug seeking after termination of use is determined by both genetic and environmental factors. Studies from several laboratories have indicated that factors such as sex (Anker and Carroll, 2010b, 2011; Becker et al., 2012; Carroll and Anker, 2010b), age (Spear, 2000), impulsivity (Carroll et al., 2008, 2009, 2012; Perry and Carroll, 2008), sweet preference (Dess et al., 1998, 2000, 2005; Carroll et al., 2008, 2012), novelty reactivity (Flagel et al., 2009; Kabbaj et al., 2000), prenatal stress (Frye et al., 2011), and avidity for exercise (Larson and Carroll, 2005) predict vulnerability to drug-seeking behavior, particularly with stimulant drugs. These vulnerability factors (Female > Male, adolescent > adult, high impulsive > low impulsive, high sweet intake > low sweet intake, high novelty reactivity > low novelty reactivity, higher avidity for exercise > lower avidity for exercise) predict elevated drug seeking throughout several phases of drug self-administration, such as initiation (Davis et al., 2008; Perry et al., 2005; Perry and Carroll, 2008; Piazza et al., 1989), escalation (Anker et al., 2009b; 2010; Perry et al., 2008), resistance to extinction after termination of drug access in rats (Belin et al., 2011; Perry et al., 2008), reinstatement of responding (relapse) after termination of drug access (Larson and Carroll, 2005; Perry et al., 2006; Perry et al., 2008), and they affect motivation levels under a progressive-ratio schedule (Belin et al., 2011; Carroll et al., 2002). Some of these predictors of drug self-administration, like impulsivity (Dallery and Raiff, 2007; Krishnan-Sarin et al., 2007; Yoon et al., 2007), also predict susceptibility to drug abuse in humans (Elman et al., 2001). For example higher vs. lower measures of impulsive behavior predict self-report of more rewarding drug effects (de Wit, 2009; Perry and Carroll, 2008).

Recent research on individual differences in drug-seeking animals indicates corresponding differences in reactivity to negative aspects related to drugs of abuse. For example, animals selected for low impulsivity (LoI vs. HiI), low saccharin intake (LoS vs. HiS), as well as adults (vs. adolescents), and males (vs. females) not only exhibit less drug seeking than their counterparts, but they also exhibit more sensitivity to punishment by histamine, greater signs of withdrawal from drugs of abuse, greater taste aversion, greater response to anxiogenic stimuli, and greater acoustic startle (Carroll et al., 2009; Carroll and Holtz, 2014; Holtz et al., 2013, 2014b; Holtz and Carroll, 2014; McLaughlin et al., 2011; Radke et al., 2014, but see Radke et al., 2013), while their counterparts (HiI, HiS, adolescents, and females, respectively) have greater response to positive aspects of drugs (i.e., greater drug-seeking and drug-taking behaviors, see review by Carroll et al., 2009). This raises the question of to what extent are individual differences in drug seeking understood based on differential reactions to positive or negative aspects of drugs. Furthermore, these differing behavioral characteristics may be accompanied by underlying neurobiological characteristics (Flagel et al., 2010; Kabbaj and Akil, 2000; Regier et al., 2012) that could interact with intervention techniques, such as treatments that aim to reduce drug seeking. Therefore, differential vulnerability to drug seeking may be an important factor for customizing prevention and treatment strategies for drug abuse in humans.

To date, there have been very few preclinical animal studies that have addressed negative aspects of drugs of abuse in terms of the development and treatment of drug abuse, and there are even fewer studies in humans (Anker and Carroll, 2012; Carroll and Holtz, 2014; Holtz et al., 2013; Holtz and Carroll, 2011, 2014). In terms of prevention, it is particularly important to know how positive vs. negative aspects of drugs will affect relapse in groups that differentially administer drugs. Therefore, interventions could be matched to differences in self-administration and the specific conditions that elicit relapse. For example, studies have shown that female animals tend to show greater drug-seeking behavior than male animals (see review by Carroll et al., 2009), and female animals are more responsive to interventions that reduce drug-seeking behavior including pharmacological (Campbell et al., 2002; Carroll et al., 2001; Cosgrove and Carroll, 2004) and behavioral methods, such as access to an alternative reinforcer (Cosgrove and Carroll 2003) or opportunity for aerobic exercise (Cosgrove et al., 2002; Zlebnik et al., 2014), available concurrently with the drug. However, in recent studies of rats selectively bred for high or low saccharin intake (HiS vs. LoS), an opposite effect occurred. The lower self-administering LoS rats reduced their rate of escalation of cocaine intake, while their higher self-administering HiS counterparts increased their cocaine escalation when treated with progesterone (Anker et al., 2012) or baclofen (Holtz and Carroll, 2011). Thus, initial evidence suggests that phenotypic differences in self-administration might determine the success of interventions aimed to reduce drug seeking.

The purpose of the present study was to further examine the reduction of reinstatement to cocaine seeking evoked by cocaine (COC), caffeine (CAFF), and yohimbine (YOH) in high (HiI) vs. low (LoI) impulsive rats treated with allopregnanolone (ALLO) or a vehicle control (VEH). Female rats were selected for HiI vs. LoI impulsivity based on their performance on a delay-discounting task that was determined by their preference for a small-immediate (HiI) vs. large-delayed food reward (LoI) as described previously (Perry et al., 2005; Perry and Carroll, 2008). Allopregnanolone has been used in previous rat studies to reduce cocaine- (Anker et al., 2009; Anker and Carroll, 2010a) and methamphetamine- (Holtz et al., 2014b) induced reinstatement of drug seeking in rats. Since ALLO, progesterone, and their precursor, pregnenolone have been show to have anxiolytic effects (Anker and Carroll, 2010a, 2011; Anker et al., 2007; Concas et al., 2000; Llaneza and Frye, 2009; Schneider and Popik, 2007), it was hypothesized that it may produce a greater reduction of stress-induced (e.g., YOH and a high dose of CAFF priming injections) responding in LoI vs. HiI animals, since LoI rats may be more sensitive to anxiogenic stimuli or other negative aspects of drugs (Holtz et al., 2013; Holtz and Carroll, 2011, 2014). Female rats were used in this study, as they show a greater difference between HiI and LoI measures of cocaine seeking than male rats (Perry et al., 2008); thus, they would provide a higher baseline of reinstatement for reduction by ALLO.

All rats were trained to self-administer iv cocaine, and their drug-seeking behavior was extinguished by substituting a saline solution. Subsequently, reinstatement responding was compared when different groups of rats were treated with ALLO or VEH before COC, CAFF, or YOH. The priming conditions were selected to simulate conditions that might elicit relapse in abstinent human drug abusers, such as COC itself, physiological stress (YOH), or a high dose of CAFF. Caffeine was included as a priming agent to serve as a model of a stimulant that is widely used in the human population and for its anxiogenic characteristics when consumed at high doses. The selected dose of CAFF (40 mg/kg) was hypothesized to have an anxiogenic effect based on evidence from previous literature. For example, an anxiogenic effect of 20 mg/kg CAFF was found in rats tested on an elevated plus maze (Gulick and Gould, 2009; Silva and Frussa-Filho, 2000), conditioned place and taste aversions were reported in rats treated with 20 mg/kg (Steigerwald et al., 1988; Myers and Izbicki, 2006) and 32 mg/kg (Vishwanath et al., 2011) CAFF, and other measures of stress such as CAFF withdrawal have been reported (Bhorkar et al., 2014). Based on Perry et al. (2008) it was hypothesized that HiI rats would reinstate responding on the drug lever more than LoI rats to a positive priming injection (COC), and LoI would exceed HiI rats on reinstatement to anxiogenic stimuli (YOH and a high dose of CAFF).

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects

Adult female Wistar rats (total n = 67) were used for this experiment (see Table 1). Estrous cycle was not monitored to prevent disruption of cocaine-maintained behavior by repeated vaginal lavage (Walker et al., 2002); therefore, results can be generalized across all phases of the estrous cycle. After a minimum of 3 days of acclimation following arrival to the laboratory, rats were housed individually in plastic holding cages and moved daily into experimental chambers for delay-discounting testing. During the self-administration period following completion of delay discounting, rats were housed in experimental chambers. For all conditions, rats were housed in temperature (24° C) - and humidity-controlled rooms where there was a 12-hr light/dark cycle (lights on at 6:00 am). Use of these animals for this protocol (1008A87754) was approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and was accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC). Recommended principles of animal care were followed (National Research Council, 2003).

Table 1. Reinstatement groups and order of priming events.

| Priming Condition | N | Reinstatement Priming Sequence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cocaine (COC) | 24 | Pretreatment | VEH | VEH | VEH | ALLO |

| Prime | SAL | COC | SAL | COC | ||

| Caffeine (CAFF) | 24 | Pretreatment | VEH | VEH | VEH | ALLO |

| Prime | SAL | CAFF | SAL | CAFF | ||

| Yohimbine (YOH) | 19 | Pretreatment | VEH | VEH | VEH | ALLO |

| Prime | SAL | YOH | SAL | YOH | ||

2.2. Delay Discounting

Adult female rats were tested on a delay-discounting task for food in experimental chambers described previously (Perry et al., 2008). These chambers were housed within a wooden sound-attenuating enclosure equipped with a ventilation fan. Each had a port for a water bottle for ad libitum water access and a 45-mg pellet feeder (Coulbourn Instrument, Lehigh Valley, PA) that was mounted on a stainless steel wall and attached to a pellet delivery trough. On either side of the pellet feeder were two standard response levers mounted about 4 cm above the cage floor. One lever delivered 1 pellet immediately after a lever press, and the other lever delivered 3 pellets after an adjusting delay. The lever that delivered 1 pellet immediately and the lever that delivered 3 pellets after an adjusting delay alternated each day. The delay was adjusted based on the rat's choices. A lever press on the immediate side decreased the delay by 1 s, and a lever press on the delayed side increased the delay by 1 s. The rats were tested at the same time 7 days a week for 2-h sessions or 60 trials (4-trial blocks), whichever came first. Sessions began with a white house light (4.6 W) and one of the sets of tricolored stimulus (situated above both levers) lights being lit. When lit, the stimulus lights indicated that the lever was active. The first two trials consisted of a forced choice on each lever with stimulus lights lit above the correct lever. The third and fourth trials consisted of a free choice on either lever with stimulus lights lit above both levers. At the end of the session, the final delay was recorded and used for the starting delay on the following day. A mean adjusted delay (MAD) score was calculated by taking the total delay divided by the number of free choice trials. Once a rat completed at least 50 trials per session for five days, and the difference in MAD scores across those five days was no greater than 5 s, an average MAD score across the five days was calculated. The rat was selected as HiI when the average MAD score was < 9 s, and the rat was selected as LoI when the average MAD score was > 13 s. Even though it was rare, rats that fell in between 9 and 13 s were excluded from the study. The rationale for these selection criteria was determined by a previous study in which Perry et al. (2005) used several rats and found a bimodal distribution that matched well to this range of numbers. Data collection and experimental programming were controlled by PC computers and MED-PC software (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT).

2.3. Cocaine self-administration

After rats were selected as HiI or LoI, they underwent catheterization surgery. They were anesthetized with ketamine (60 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) and received atropine (0.15 mL) and doxapram (5 mg/kg) to facilitate respiration. A chronic indwelling polyurethane catheter (MRE-040-S-20, Braintree Scientific, Inc., Braintree, MA) was implanted in the right jugular vein. The other end of the catheter was led subcutaneously to an incision made medial and 1 cm caudal from the scapulae and was connected to the cannula embedded in an infusion harness (Instech Laboratories, Plymouth Meeting, PA). For 3 days after surgery, rats were given heparin (0.2 mL, 50 units/mL, iv) to prevent clotting in the catheter and baytril (2.0 mg/kg, iv) to prevent infection.

After the 3-day recovery period, rats were trained to self-administer cocaine (0.4 mg/kg) in experimental chambers identical to the delay-discounting procedure, except that instead of a pellet dispenser, there was a holder for a jar containing ground food. In addition, there was a syringe pump that contained a 30-ml syringe that delivered COC or SAL into the operant chamber via a tether (C31CS; Plastics One, Roanoke, VA), connected on one end to the rat harness and to a swivel (050-0022, Alice King Chatham, Hawthorne, CA) on the other end. The rats were trained under an FR-1 reinforcement schedule during daily 2-h training sessions. A house light automatically turned on at 9 am every morning signaling the beginning of the session. During this time, a lever press on one lever (active lever) resulted in activation of tricolored stimulus lights above the lever and activation of the pump, which delivered intravenous cocaine at a volume of 0.025 mL/100 g body weight (duration = 1 s/100 g). Responses on the other lever (inactive lever) resulted in illumination of stimulus lights above the lever but had no other programmed consequences.

During acquisition, responding by rats was facilitated by baiting the lever with peanut butter and providing non-contingent infusions. Rats were required to earn 25 or more infusions a session and to maintain a 2:1 ratio of active vs. inactive lever responses for 3 consecutive sessions. Once rats could reliably meet these criteria without the lever being baited or non-contingent infusions being provided, they entered the maintenance phase, where their responses and infusions were monitored and recorded for 12 days. During this time, catheters and tethers were checked daily for leaks with a heparin/saline solution, and every 5-7 days catheters were checked for patency by flushing with an iv solution (Caine et al., 1999) containing 30 mg/ml ketamine, 1.5 mg/ml midazolam, and saline (0.1 – 0.2 ml, iv). Patency was inferred by loss of righting reflex. After 12 days of rats maintaining at least 25 infusions per session with a 2:1 active to inactive lever responses, the extinction period began.

The extinction phase lasted for 16 days, and the consequences of lever responding remained identical to maintenance, except that COC was replaced with SAL. After extinction, and for 3 days prior to reinstatement, the stimulus lights, syringe pump, and house light were disconnected. Responses on both levers during this pre-reinstatement period were recorded but had no programmed consequences.

Subsequently, the rats entered into the reinstatement period, where they were divided into 3 separate groups. Lights and pump remained off during this time, and rats received alternating ip injections of saline (SAL) and drug solution (COC, CAFF, or YOH) with pretreatment 30 min before each daily session with either peanut oil (VEH) or ALLO (15 mg/kg). Each drug and VEH or ALLO combination was administered only once, with SAL and VEH combination being administered on days in between the administration of drug and VEH or ALLO combination (Table 1).

2.4. Drugs

Cocaine HCL was provided by the National Institute of Drug Abuse (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC). It was dissolved in sterile 0.9% saline, and the anticoagulant heparin (1 ml heparin/200 ml of saline) was added to prevent thrombin accumulation. Caffeine and ALLO were obtained from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and dissolved in saline (40 mg/ml) and peanut oil (15 mg/kg), respectively. Yohimbine (2.5 mg/ml) was obtained from Lloyd Laboratories (Shenandoah, IA) and came in an injectable form.

2.5. Data Analysis

Primary dependent measures included MADs during the delay discounting task, responses and infusions during maintenance and extinction of self-administration, and responses during reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior. Repeated measures were days during maintenance and extinction and injection type during reinstatement. Outlying values within each group that were two standard deviations outside of the mean were excluded from analysis. MADs were compared between HiI and LoI rats using an unpaired 2-tailed Student's t-test. For maintenance and extinction, responses and infusions were averaged across 4-day blocks to reduce variability and the number of post hoc contrasts and were analyzed using a 2-factor mixed ANOVA (phenotype X days). For reinstatement, groups that received different priming injections (e.g., COC, CAFF, YOH) were analyzed separately using 2-factor mixed ANOVA (phenotype X priming injection, e.g. VEH/COC, ALLO/COC). Dunn's (Bonferroni) procedure was used for post hoc analyses, and results were considered significant if p < 0.05. All analyses were completed using GBStat (Dynamic Microsystems, Silver Spring, MD).

3. Results

3.1. Mean Adjusted Delay

Confirming behavioral phenotype, mean HiI MAD scores (4.71 ± 0.33) were significantly lower than mean LoI MAD scores (20.67 ± 1.44) (t(65) = 11.17 , p <0.0001).

3.2. Maintenance

Mean responses and infusions (4-day blocks) for the cocaine self-administration maintenance period are shown in Tables 2 and 3. Results of the 2-factor ANOVA revealed no significant main effect of phenotype or day and no significant phenotype X day interaction for responses (Table 2) or infusions (Table 3).

Table 2. Mean (± SEM) responses during maintenance and extinction.

| Phase | Blocks of 4 days | HiI Responses | LoI Responses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maintenance | Days 1-4 | 50.60 ± 1.60 | 50.07 ± 1.32 |

| Days 5-8 | 49.63 ± 1.91 | 53.55 ± 1.87 | |

| Days 9-12 | 46.52 ± 1.35 | 53.30 ± 1.76 | |

| Extinction | Days 1-4 | 29.52 ± 2.27 | 32.42 ± 2.62 |

| Days 5-8 | 11.28 ± 0.99 | 8.68 ± 0.80 | |

| Days 9-12 | 6.63 ± 0.63 | 5.4 ± 0.69 | |

| Days 13-16 | 3.90 ± 0.43 | 3.76 ± 0.50 |

Table 3. Mean (± SEM) infusions during maintenance and extinction.

| Phase | Blocks of 4 days | HiI Infusions | LoI Infusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maintenance | Days 1-4 | 40.41 ± 1.03 | 38.40 ± 0.91 |

| Days 5-8 | 39.79 ± 1.06 | 41.24 ± 1.14 | |

| Days 9-12 | 38.44 ± 1.07 | 42.79 ± 1.37 | |

| Extinction | Days 1-4 | 22.38 ± 1.66 | 26.22 ± 2.06 |

| Days 5-8 | 8.54 ± 1.66 | 6.38 ± 0.55 | |

| Days 9-12 | 4.69 ± 0.70 | 3.88 ± 0.44 | |

| Days 13-16 | 2.75 ± 0.32 | 2.81 ± 0.36 |

3.3. Extinction

Tables 2 and 3 display the mean number of responses (4-day blocks) over the 16-day extinction period. While there was no significant main effect of phenotype or a phenotype X day interaction, there was a significant main effect of day (F(3,267) = 171.80, p < 0.0001), indicating a decrease in responding over the extinction period for all rats.

Saline infusions (Table 3) over the extinction period were analyzed similarly. Results indicated no significant main effect of phenotype but a significant main effect of day (F(3,267) = 128.37, p < 0.0001) and phenotype X day interaction (F(3,267) = 2.74, p < 0.05). Post hoc analyses revealed a notable decline in responding in all rats over the extinction period but no differences between the HiI and LoI rats.

3.4. Reinstatement

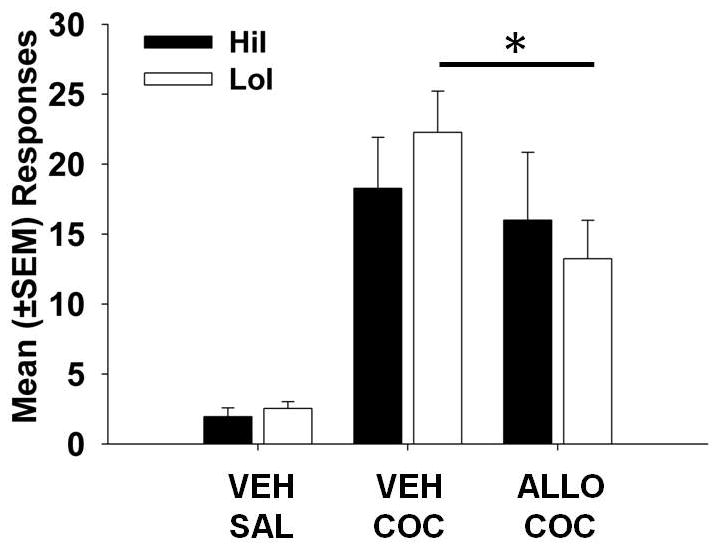

3.4.1. Cocaine-Primed Reinstatement

Cocaine-seeking responses primed by cocaine are displayed in Figure 1. Results indicated no significant main effect of phenotype or phenotype X priming injection interaction, but there was a main effect of priming injection (F(1,45) = 10.41, p < 0.01). Post-hoc analyses revealed that ALLO significantly reduced COC-primed responding in LoI (p < 0.01) but not HiI rats.

Figure 1.

Mean (±SEM) responses for cocaine- (COC) primed reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior. Pretreatment with allopregnanolone (ALLO) attenuated cocaine-seeking responses in low (LoI) but not high (HiI) impulsive rats. * indicates p < 0.05.

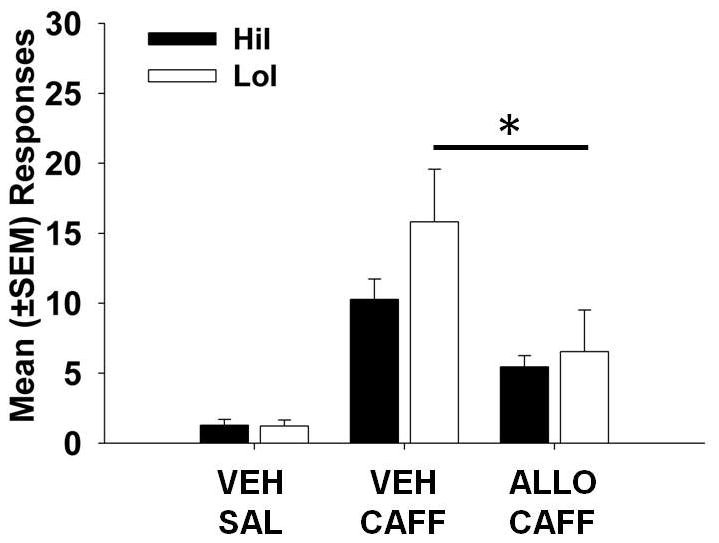

3.4.2. Caffeine-Primed Reinstatement

Results for CAFF-induced cocaine seeking are displayed in Figure 2. While there was no significant main effect of phenotype and no phenotype X priming injection interaction, there was a main effect of priming injection (F(1,43) = 12.49, p < 0.01). Post-hoc analyses revealed that ALLO significantly reduced CAFF-induced responding in LoI (p < 0.05) but not HiI rats.

Figure 2.

Mean (±SEM) responses for caffeine- (CAFF) primed reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior. Pretreatment with allopregnanolone (ALLO) attenuated cocaine-seeking responses in low (LoI) but not high (HiI) impulsive rats. * indicates p < 0.05.

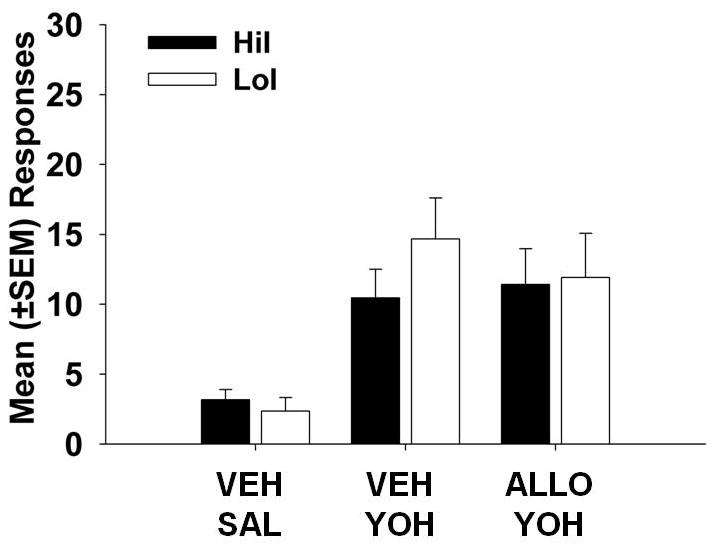

3.4.3. Yohimbine-Primed Reinstatement

Yohimbine-induced cocaine-seeking responses are displayed in Figure 3. There were no significant main effects of phenotype or priming injection and no phenotype X priming injection interaction.

Figure 3.

Mean (±SEM) responses for yohimbine- (YOH) primed reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in low (LoI) and high (HiI) impulsive rats. No significant differences were found.

4. Discussion

One goal of this study was to compare HiI and LoI rats on a cocaine self-administration, extinction, and reinstatement (relapse) procedure to determine whether there were phenotype differences (HiI vs. LoI) in response to treatment with ALLO (vs. VEH). Previous work with HiI and LoI rats indicated that HiI rats acquired cocaine self-administration faster than LoI rats (Perry et al., 2008), they escalated their intake more than LoI rats (Anker et al., 2009b), and they showed higher levels of reinstatement responding than LoI rats when given a priming injection of 15 mg/kg but not 10 mg/kg cocaine (Perry et al., 2008). The reinstatement results from the present study differed from previous results that showed greater reinstatement in HiI vs. LoI, which may have been due to slightly different reinstatement procedures. Little is known, however, regarding how HiI vs. LoI and other animals that differentially administer drugs respond to interventions aimed to reduce drug seeking. The present results indicated that LoI rats reduced their drug seeking more than HiI rats when treated with ALLO (Figs. 1 and 2).

The result that ALLO attenuated reinstatement more in LoI rats than HiI rats was consistent with recent studies involving phenotypes, such as high (HiS) vs. low (LoS) saccharin-preferring rats that were treated with progesterone (Anker et al., 2012) or baclofen (Holtz and Carroll, 2011) during long-access to cocaine self-administration. There was a more marked effect of progesterone and baclofen in LoS than HiS rats compared to their vehicle controls. In these previous studies, as well as the present study, the lower drug-seeking phenotype had better success than the higher drug-seeking phenotype with interventions aiming to reduce drug-motivated responding. The baseline rates of behavior before ALLO administration were equal in all of these studies, with no phenotypic differences in maintenance or extinction; thus, the different treatment effects could not be explained by different baseline rates of drug seeking.

While these initial studies with the HiI vs. LoI and HiS vs. LoS rats suggest greater reductions in drug-seeking behavior by pharmacological interventions in the low drug-seeking phenotype, studies comparing other vulnerability characteristics, such as sex, show different results. For example, female rats generally show greater drug self-administration behavior than male rats (see reviews; Anker and Carroll, 2011; Carroll et al., 2008, 2009; Carroll and Anker, 2010), but when treated with medications such as baclofen (Campbell et al., 2002), ketoconazole (Carroll et al., 2001), or behavioral interventions such as a nondrug rewards (Cosgrove et al., 2002), female rats consistently showed greater reductions in cocaine or opioid self-administration than male rats. This opposite response (females > males) to interventions aimed to reduce drug self-administration compared to the other phenotypes (LoS > HiS, LoI > HiI) may be related to hormonal status (e.g., progesterone in females). Progesterone and its metabolites (e.g., ALLO) reduce cocaine-seeking behavior through several phases of the addiction process in female rats more than male rats (see Anker and Carroll, 2010b; Carelli, 2002). Thus, endogenous progesterone may have enhanced the other pharmacological and behavioral interventions in female rats but not male rats.

The present results with ALLO are consistent with previous findings that progesterone and its metabolite ALLO (Anker et al., 2009a) decreased cocaine-primed reinstatement in female rats. Elevated progesterone levels in freely-cycling female rats were also associated with decreased cocaine–induced reinstatement (Feltenstein and See, 2007). Finasteride, a 5-alpha reductase inhibitor that blocks the metabolism of progesterone to ALLO also blocked the attenuating effects of progesterone on cocaine-primed reinstatement (Anker et al., 2009a). Thus, progesterone's inhibitory effect on cocaine seeking in females may be through its metabolite, ALLO. The behavioral effects of ALLO may be explained by its indirect modulation of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens and ventral tegmental areas of the brain (Carelli, 2002; Rutsuko et al., 2004) and by acting as a potent positive allosteric modulator of GABAA-receptors (for reviews see Lambert et al., 1995; Gasior et al., 1999). Another mechanism of ALLO, that is not mutually exclusive, is its ability to alter stress- and cocaine-related hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) activation, which is increased by stress- (Stewart, 2000; Weiss et al., 2001), and cue-induced (Goeders and Clampitt, 2002) reinstatement. ALLO has been shown to reduce HPA activation by decreasing corticotropin-releasing hormone levels (Patchev et al., 1994) and preventing increases in plasma corticosterone following stress (Owens et al., 1992).

Another goal of the present study was to determine whether the effectiveness of ALLO to reduce reinstatement was related to the priming condition: specifically, whether it was considered rewarding or anxiogenic. We used three different priming conditions, COC, CAFF, and YOH to represent positive (COC) or negative (CAFF, YOH) pharmacological stimuli that have been reported to elicit drug-seeking behavior formerly rewarded by cocaine. In previous studies of individual differences in drug seeking, results demonstrated differential responding to the positive and negative aspects of drug taking in HiS and LoS rats. While HiS rats exceeded LoS rats in drug intake (Perry et al., 2006, Anker et al., 2012) and reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior (Perry et al., 2006), LoS rats (vs. HiS) revealed greater reactivity to negative events, such as food restriction (Carroll et al., 2012) and withdrawal from ethanol (Dess et al., 2005), glucose (Yakavenko et al., 2011) morphine (Holtz et al., 2014b), and cocaine (Radke et al., 2014). Given the previous finding that lower drug-seeking animals respond more to negative aspects of drugs compared to higher drug-seeking animals, one potential explanation for the results that ALLO reduced reinstatement more in LoI than HiI rats is that these pharmacological manipulations produced more of a stress response in LoI rats compared to HiI rats. Cocaine has been shown to induce stress hormones, which is attenuated by ALLO (Frye, 2007), and it is possible that COC and a high dose of CAFF differentially affect stress pathways in LoI and HiI rats. Previous work has shown an induction of ALLO by COC (Kohtz et al., 2010). Therefore, another explanation is that HiI and LoI rats could produce different levels of ALLO in response to COC and CAFF, so that treatment with ALLO might affect HiI and LoI differently. Further work is needed to investigate potential differences of stress hormones and levels of ALLO in response to pharmacological manipulations in HiI and LoI rats.

While current results yielded phenotype differences in response to treatment with ALLO (Fig. 3A and Fig. 3B), results did not demonstrate differential reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior primed by COC, CAFF or YOH injections under control conditions in the HiI and LoI rats. Further work is needed to fully examine the type of priming stimuli and the role of their positive (COC) and negative (high dose of CAFF, YOH) pharmacological effects. The finding of similar results in HiI vs. LoI and HiS vs. LoS rats (i.e., that behavior was alleviated by treatment with ALLO in females) is important, because common substances such as CAFF may provoke substantial relapse in cocaine-abstinent individuals, and common neurobiological mechanisms may underlie these effects. Improved strategies to reduce drug-seeking behavior are needed and translational significance may result from a better understanding of these individual differences and a range of environmental events that prompt relapse.

In summary, the present results indicate that LoI rats exhibited greater reductions than HiI rats in COC and CAFF-primed reinstatement due to treatment of ALLO. Recent evidence suggests a role for ALLO and its precursors, progesterone (Anker et al., 2010b) and pregnenolone (Valee et al., 2014), in the development and treatment of various forms of drug addiction. The present findings emphasize the potential success of matching effective interventions to reduce drug seeking to individual differences in drug self-administration. Results from this study show greater reduction of reinstatement for lower drug-seeking animals using a novel therapeutic approach, ALLO, that attenuated COC- and CAFF-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior. Further studies will be needed in order to discover interventions that will be successful in reducing drug-motivated behavior in higher drug-seeking animals.

Highlights.

Rats selected as high or low impulsive exhibit high and low drug-seeking behaviors, respectively.

Low drug-seeking rats exhibit greater receptivity to interventions aimed to reduce drug-seeking behavior.

Rats were selected as high or low impulsive on a delay-discounting task then trained to self-administer cocaine.

Reinstatement was elicited by positive (cocaine) and negative (yohimbine, high dose caffeine) stimuli.

Allopregnanolone reduced reinstatement of cocaine seeking in low impulsive but not high impulsive rats.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Justin Anker, Thomas Baron, Katie Bressler, Nathan Holtz, Seth Johnson, Sean Navin, Amy Saykao, Rachael Turner, Aneal Rege, Tyler Rehbein, Troy Velie, and Jeremy Williams for technical assistance.

Role of Funding Source: This study was supported by NIDA grants R01 DA003240 (MEC) and K05 DA015267 (MEC).

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors have approved of and contributed to the final manuscript. MEC and PSR were involved with the design of the experiment and graphic presentation. MEC, PSR, and NEZ were involved with the data analysis. PSR and ABC were involved with directing the daily experimental procedures. PSR, ABC, and NEZ were involved with the data collection.

Conflict of interest: No conflict declared.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anker JJ, Carroll ME. Females are more vulnerable to drug abuse than males: evidence from preclinical studies and role of ovarian hormones. In: Neill JC, Kulkarni J, editors. Biological Basis of Sex Differences in Psychopharmacology. Vol. 8. Springer; London: 2011. pp. 73–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anker JJ, Carroll ME. Sex differences in the effects of allopregnanolone on yohimbine-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking in rats. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010a;107:264–267. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anker JJ, Carroll ME. The role of progestins in the behavioral effects of cocaine and other drugs of abuse: human and animal research. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010b;35:315–333. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anker JJ, Holtz NA, Carroll ME. Effects of progesterone on escalation of intravenous cocaine self-administration in rats selectively bred for high or low saccharin intake. Behav Pharmacol. 2012;23:205–2010. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32834f9e37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anker JJ, Holtz NA, Zlebnik N, Carroll ME. Effects of allopregnanolone on the reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in male and female rats. Psychopharmacology. 2009a;203:63–72. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1371-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anker JJ, Larson EB, Gliddon LA, Carroll ME. Effects of progesterone on the reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in female rats. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;15:472–480. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.5.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anker JJ, Perry JL, Gliddon LA, Carroll ME. Impulsivity predicts the escalation of cocaine self-administration in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009b;93:343–348. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anker JJ, Zlebnik NE, Carroll ME. Differential effects of allopregnanolone on the escalation of cocaine self-administration and sucrose intake in female rats. Psychopharmacology. 2010;212:419–429. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1968-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker JB, Perry AN, Westenbroek C. Sex differences in the neural mechanisms mediating addiction: a new synthesis and hypothesis. Biol Sex Differ. 2012;3:14–35. doi: 10.1186/2042-6410-3-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belin D, Berson N, Balado E, Piazza PV, Deroche-Gamonet V. High-novelty preference rats are predisposed to compulsive cocaine self-administration. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:569–579. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhorkar AA, Dandekar MP, Nekhate KT, Subhedar NK, Kokare DM. Involvement of the central melanocortin system in the effects of caffeine on anxiety-like behavior in mice. Life Sci. 2014;95:72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2013.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caine SB, Negus SS, Mello NK. Method for training operant responding and evaluating cocaine self-administration behavior in mutant mice. Psychopharmacology. 1999;147:22–24. doi: 10.1007/s002130051134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell UC, Morgan AD, Carroll ME. Sex differences in the effect of baclofen on the acquisition of cocaine self-administration in rats. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;66:61–69. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(01)00185-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carelli RM. Nucleus accumbens cell firing during goal-directed behaviors for cocaine vs. ‘natural’ reinforcement. Physiol Behav. 2002;76:379–387. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(02)00760-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll ME, Anker JJ. Sex differences and ovarian steroid hormones in animal models of drug dependence. Horm Behav. 2010;58:44–56. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll ME, Anker JJ, Perry JL. Modeling risk factors for nicotine and other drug abuse in the preclinical laboratory. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;104:S70–S78. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll ME, Campbell UC, Heideman P. Ketoconazole suppresses food restriction-induced increases in heroin self-administration in rats: sex differences. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;9:307–316. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.9.3.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll ME, Holtz NA. The relationship between feeding and drug-seeking behaviors. In: Brewerton TD, Dennis AB, editors. Eating Disorders, Addictions and Substance Use Disorders: Research, Clinical and Treatment Aspects. Springer-Verlag; New York: 2014. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll ME, Holtz NA, Zlebnik NE. Saccharin preference in rats: relation to impulsivity and comorbid drug intake. In: Avena NM, editor. Animal Models of Eating Disorders. Springer-Verlag; New York: 2012. pp. 201–234.pp. 380 [Google Scholar]

- Carroll ME, Morgan AD, Anker JJ, Perry JL. Selective breeding for differential saccharin intake as an animal model of drug abuse. Behav Pharmacol. 2008;19:435–460. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32830c3632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll ME, Morgan AD, Campbell UC, Lynch WJ, Dess NK. Intravenous cocaine and heroin self-administration in rats selectively bred for differential saccharin intake: phenotype and sex differences. Psychopharmacology. 2002;161:304–313. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1030-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Concas A, Porcu P, Sogliano C, Serra M, Purdy RH, Biggio G. Caffeine-induced increases in the brain and plasma concentrations of neuroactive steroids in the rat. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000;66:39–45. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00237-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove KP, Carroll ME. Differential effects of a nondrug reinforcer, saccharin, on oral self-administration of phencyclidine (PCP) in male and female rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology. 2003;170:9–16. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1487-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove KP, Carroll ME. Effects of bremazocine on oral phencyclidine (PCP) self-administration in male and female rhesus monkeys. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;12:111–117. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.12.2.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove KP, Hunter R, Carroll ME. Wheel-running attenuates intravenous cocaine self-administration in rats: sex differences. Pharm Biochem Behav. 2002;73:663–671. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)00853-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallery J, Raiff BR. Delay discounting predicts cigarette smoking in a laboratory model of abstinence reinforcement. Psychopharmacology. 2007;190:485–96. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0627-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis BA, Clinton SM, Akil H, Becker JB. The effects of novelty-seeking phenotypes and sex differences on acquisition of cocaine self-administration in selectively bred high-responder and low-responder rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;90:331–338. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dess NK, Arnal J, Chapman CD, Siebel S, VenderWeele DA, Green K. Exploring adaptations to famine: rats selectively bred for differential saccharin intake differ on deprivation-induced hyperactivity and emotionality. Int J Comp Psychol. 2000;13:34–512. [Google Scholar]

- Dess NK, Badia-Elder NE, Thiele TE, Kiefer SW, Blizard DA. Ethanol consumption in rats selectively bred for differential saccharin intake. Alcohol. 1998;16:275–8. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(98)00010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dess NK, O'Neil P, Chapman CD. Ethanol withdrawal and proclivity are inversely related in rats selectively bred for differential saccharin intake. Alcohol. 2005;37:9–22. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H. Impulsivity as a determinant and consequence of drug use: a review of underlying processes. Addict Biol. 2009;14:22–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00129.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elman I, Krause S, Karlsgodt K, Schoenfiel DA, Gollub RL, Beriter HC, Gastfriend DR. Clinical outcomes following cocaine infusion in nontreatment-seeking individuals with cocaine dependence. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49:553–555. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)01096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltenstein MW, See RE. Plasma progesterone levels and cocaine-seeking in freely cycling female rats across the estrous cycle. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;89:183–189. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flagel SB, Akil H, Robinson TE. Individual differences in the attribution of incentive salience to reward-related cues; implications for addiction. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56:139–148. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flagel SB, Robinson TE, Clark JJ, Clinton SM, Watson SJ, Seeman P, Phillips PE, Akil H. An animal model of genetic vulnerability to behavioral disinhibition and responsiveness to reward-related cues: implications for addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:388–400. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye CA, Paris JJ, Osborne DM, Campbell JC, Kippin TE. Prenatal stress alters progestogens to mediate susceptibility to sex-typical, stress-sensitive disorders, such as drug abuse: a review. Front Psychiatry. 2011;2:1–15. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2011.00052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye CA. Progestins influence motivation, reward, conditioning, stress, and/or response to drugs of abuse. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007;2:209–19. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasoir M, Carter RB, Witkin JM. Neuroactive steroids: potential therapeutic use in neurological andpsychiatric disorders. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1999;20:107–112. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01318-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goeders NE, Clampitt DM. Pothetial role for the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis in the conditioned reinforcer-induced reinstatment of extinguished cocaine seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2002;16:222–232. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulick D, Gouild TJ. Effects of ethanol and caffeine on behavior in C57BL/6 mice in the plus-maze discriminative avoidance task. Behav Neurosci. 2009;123:1271–8. doi: 10.1037/a0017610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtz NS, Anker JJ, Regier PS, Claxton A, Carroll ME. Cocaine self-administration punished by i.v. histamine in rat models of high and low drug abuse vulnerability: effect of saccharin preference, impulsivity, and sex. Physiol Behav. 2013;122:32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtz NA, Carroll ME. Animal models of addiction: genetic influences. In: Kim YK, Gewirtz J, editors. Animal Models for Behavior Genetics Research Handbook of Behavior Genetics. Vol. 7. Springer; London, UK: 2014. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Holtz NA, Carroll ME. Baclofen has opposite effects on escalation of i.v. cocaine self-administration in rats selectively bred for high (HiS) and low (LoS) saccharin intake. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2011;100:275–283. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2011.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtz NA, Lozama A, Prisinzano TE, Carroll ME. Reinstatement of methamphetamine seeking in male and female rats treated with modafinil and allopregnanolone. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;120:233–237. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtz NA, Radke AK, Gewirtz JC, Carroll ME. Morphine withdrawal-induced potentiation of the acoustic startle reflex and conditioned place aversion in Lewis (LEW) and Fischer (F344) rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2014a Submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Holtz NA, Radke AK, Zlebnik NE, Harris AC, Carroll ME. Intracranial self-stimulation reward thresholds during morphine withdrawal in rats selectively bred for high (HiS) and low (LoS) saccharin intake. Brain Res. 2014b doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.01.004. submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husdon A, Stamp JA. Ovarian hormones and propensity to drug relapse: a review Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 2011;35:427–436. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabbaj M, Akil H. Individual differences in novelty-seeking behavior in rats: a c-fos study. Neuroscience. 2001;106:535–545. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00291-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabbaj M, Devine DP, Savage VR, Akil H. Neurobiological correlates of individual differences in novelty-seeking behavior in the rat: differential expression of stress-related molecules. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6983–6988. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-18-06983.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosten TA, Ambrosio E. HPA axis function and drug addictive behaviors: Insights from studies with Lewis and Fischer 344 inbred rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2002;27:35–69. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(01)00035-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohtz AS, Paris JJ, Frye CA. Low doses of cocaine decrease, and high doses increase, anxiety-like behavior and brain progestogen levels among intact rats. Horm Behav. 2010;57:474–480. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan-Sarin S, Reynolds B, Duhig AM, Smith A, Liss T, McFetridge A, Cavallo DA, Carroll KM, Potenza MN. Behavioral impulsivity predicts treatment outcome in a smoking cessation program for adolescent smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88:79–82. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert JJ, Belelli D, Hill-Venning C, Peters JA. Neurosteroids and GABAA receptor function. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1995;16:295–303. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)89058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson EB, Carroll ME. Wheel-running as a predictor of cocaine self-administration and reinstatement in female rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2005;82:590–600. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llaneza DC, Frye CA. Progestogens and estrogen influence impulsive burying and avoidant freezing behavior of naturally cycling and ovariectomized rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009;93:337–342. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch WJ, Sofuoglu M. Role of progesterone in nicotine addiction: evidence from initiation to relapse. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;18:451–461. doi: 10.1037/a0021265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin IB, Dess NK, Chapman CD. Modulation of methylphenidate effects on wheel running and acoustic startle by acute food deprivation in commercially and selectively bred rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2011;97:500–508. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers KP, Izbicki EV. Reinforcing and aversive effects of caffeine measured by flavor preference conditioning in caffeine-naive and caffeine-acclimated rats. Physiol Behav. 2006;88:585–96. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Guidelines For The Care And Use Of Mammals In Neuroscience And Behavioral Research. The National Academies; Washington D.C.: 2003. p. 209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens MJ, Ritchie JC, Nemeroff CB. 5 alpha-Pregnane-3 alpha,21-diol-20-one(THDOC) attenuates mild stress-induced increases in plasma corticosterone via a non-glucocorticoid mechanism: comparison with alprazolam. Brain Res. 1992;573:353–355. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90788-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patchev VK, Hayashi S, Orikasa C, Almeida OB. Implications of estrogen-dependent brain organization for gender differences in hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal regulation. FASEB J. 1995;9:419–423. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.5.7896013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry JL, Carroll ME. The role of impulsive behavior in drug abuse. Psychopharmacology. 2008;200:1–26. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1173-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry JL, Dess NK, Morgan AD, Anker JJ, Carroll ME. Escalation of IV cocaine self-administration and reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in rats selectively bred for high and low saccharin intake. Psychopharmacology. 2006;186:235–245. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0371-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry JL, Larson EB, German JP, Madden GJ, Carroll ME. Impulsivity (delay discounting) as a predictor of acquisition of i.v. cocaine self-administration in female rats. Psychopharmacology. 2005;178:193–201. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1994-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry JL, Nelson SE, Carroll ME. Impulsive choice as a predictor of acquisition of i.v. cocaine self-administration and reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in male and female rats. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;16:165–177. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.16.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza PV, Deminiere JM, Le Moal M, Simon H. Factors that predict individual vulnerability to amphetamine self-administration. Science. 1989;245:1511–1513. doi: 10.1126/science.2781295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radke AK, Holtz NA, Gewirtz JC, Carroll ME. Reduced emotional signs of opiate withdrawal in animals selectively bred for low (LoS) versus high (HiS) saccharin intake. Psychopharmacology. 2013;227:117–126. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2945-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radke AK, Zlebnik NE, Carroll ME. Cocaine reward and withdrawal in rats selectively bred for low (LoS) versus high (HiS) saccharin intake. Psychopharmacology. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2014.11.022. Revision submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regier PS, Carroll ME, Meisel RL. Cocaine-induced c-Fos expression in rats selectively bred for high or low saccharin intake and in rats selected for high or low impulsivity. Behav Brain Res. 2012;233:271–279. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutsuko I, Robbins TW, Everitt B. Differential control over cocaine-seeking behavior by nucleus accumbens core and shell. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:389–397. doi: 10.1038/nn1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider T, Popik P. Attenuation of estrous cycle-dependent marble burying in female rats by acute treatment with progesterone and antidepressants. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;21:651–659. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva RH. The plus-maze discriminative avoidance task: a new model to study memory-anxiety interactions. Effects of chlordiazepoxide and caffeine. J Neurosci Methods. 2000;102:117–25. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(00)00289-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP. The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000;24:417–463. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steigerwald ES, Rusiniak KW, Eckel DL, O'Reagan MH. Aversive conditioning properties of caffeine in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1988;31:579–84. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(88)90233-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart J. Pathways to relapse: the neurobiology of drug- and stress-induced relapse to drug-taking. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2000;25:125–136. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valee M, Vitiello S, Bellocchio L, Hebert-Chatelain E, Monlezun S, Martin-Garcia E, Kasaetz F, Baillie GL, Panin F, Cathala A, Roullot-Lacarriere V, Fabre S, Hurst DP, Lynch DL, Shore DM, Deroche-Gamonet V, Spampinato U, Revest JM, Maldonado R, Reggio PH, Ross RA, Marsiacano G, Piazza PV. Pregnenolone can protect the brain from cannabis intoxication. Science. 2014;343:2014. doi: 10.1126/science.1243985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker QD, Nelson CJ, Smith D, Kuhn CM. Vaginal lavage attenuates cocaine-stimulated activity and establishes place preference in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;73:743–752. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)00883-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss F, Ciccocioppo R, Parsons LH, Katner S, Liu X, Zorilla EP, Valdez GR, Bn-Shahar O, Angeletti S, Richter RR. Compulsive drug-seeking behavior and relapse. Neuroadaptation, stress, and conditioning factors. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2002;937:1–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vishwanath JM, Desko AG, Riley AL. Caffeine-induced taste aversions in Lewis and Fischer rat strains: differential sensitivity to the aversive effects of drugs. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2011;100:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2011.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon JH, Higgins ST, Heil SH, Sugarbaker RJ, Thomas CS, Badger GJ. Delay discounting predicts postpartum relapse to cigarette smoking among pregnant women. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;15:176–186. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.2.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakovenko V, Speidel ER, Chapman CD, Dess NK. Food dependence in ratsselectively bred for low versus high saccharin intake: Implications for “food addiction”. Appetite. 2011;57:397–400. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlebnik NE, Saykao AT, Carroll ME. Effects of combined exercise and progesterone treatments on cocaine seeking in male and female rats. Psychopharmacology. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3513-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]