Abstract

This trial assessed the feasibility, acceptability, tolerability, and efficacy of an Internet-based therapist-assisted cognitive-behavioral indicated prevention intervention for prolonged grief disorder (PGD) called Healthy Experiences After Loss (HEAL). Eighty-four bereaved individuals at risk for PGD were randomized to either an immediate treatment group (n = 41) or a waitlist control group (n=43). Assessments were conducted at four time-points: prior to the wait-interval (for the waitlist group), pre-intervention, post-intervention, 6 weeks later, and 3 months later (for the immediate group only). Intent-to-treat analyses indicated that HEAL was associated with large reductions in prolonged grief (d=1.10), depression (d=.71), anxiety (d=.51), and posttraumatic stress (d=.91). Also, significantly fewer participants in the immediate group met PGD criteria post-intervention than in the waitlist group. Pooled data from both groups also yielded significant reductions and large effect sizes in PGD symptom severity at each follow-up assessment. The intervention required minimal professional oversight and ratings of satisfaction with treatment and usability of the Internet interface were high. HEAL has the potential to be an effective, well-tolerated tool to reduce the burden of significant pre-clinical PGD. Further research is needed to refine HEAL and to assess its efficacy and mechanisms of action in a large-scale trial.

Keywords: Internet-based intervention, prolonged grief, prevention, cognitive behavior therapy

The death of a loved one can trigger prolonged grief disorder (PGD; Prigerson et al., 2009). Symptoms of PGD are distinguishable from normal, uncomplicated grief, bereavement-related depression and anxiety symptoms, and posttraumatic stress disorder (e.g., Barnes, Dickstein, Maguen, Neria, & Litz, 2012; Boelen & van den Bout, 2005; Bonanno et al., 2002; Prigerson et al., 1995; 1996). Bereavement is a well-established risk factor for illness, disability and death (Buckley et al., 2012; Mostofsky et al., 2012; Kaprio et al. 1987). Specifically, among the bereaved, those with syndromal level PGD have been shown to have heightened levels of suicidal thinking and behaviors, poor sleep, reduced quality of life, impaired social functioning, more health complaints, and days of work missed compared to those without syndromal level PGD (Boelen & Prigerson, 2007; Bonanno, Moskowitz, Papa, & Folkman, 2007; Chen et al., 1999; Lannen et al. 2008; Latham & Prigerson, 2004; Lichtenthal et al. 2011; Prigerson et al. 1995; 1996; 1997; 2009). Consensus criteria for PGD have been validated (Prigerson et al., 2009) and will be used in the ICD-11 (Maercker et al., 2013).

Although there are specialized evidence-based psychotherapies for PGD (e.g., Shear et al., 2005), there are no evidence-based approaches to prevent PGD, nor to address the suffering of individuals with clinical levels of distress and impairment in the early months post-loss. If PGD can be prevented, substantial pre-clinical suffering and functional impairment can be alleviated. Further, intervening early, when many bereaved are still interacting with caring family members or care-providers and actively processing the loss, may be more palatable and less distressing than waiting until enough time has passed for a PGD diagnosis (see Maercker et al., 2013), at which point most will be more isolated and not seek or receive the care they need (Lichtenthal et al. 2011).

Yet, there is good reason to be cautious about early interventions applied across too wide a range of bereavement-related distress (Litz, Gray, Bryant, & Adler, 2002; Schut, Stroebe, van den Bout, & Terheggen, 2001; Wittouck, Van Autreve, De Jaegere, Portzky, & van Heeringen, 2011). Concerns have been raised that bereavement interventions may interfere with the natural healing processes required for healthy adjustment to loss (e.g., Kleinman, 2012), and some have argued that any early degree of distress and impairment associated with bereavement is normative and should not trigger intervention (Bonanno, 2005). Indeed, most bereaved do not need or want, nor will they benefit from, interventions designed to ameliorate normative grief. Selective prevention (see Muñoz, Mrazek, & Haggerty, 1996) efforts (chiefly grief counseling) assume that in many loss contexts, especially mass-casualty events, all bereaved persons need help to recover. This can be intrusive, presumptuous, and wasteful of time and effort because most grief reactions do not entail serious and impairing distress (see Litz, 2006).

By contrast, indicated prevention strategies, which target individuals with significant and impairing pre-clinical symptoms, are more efficacious and a better use of limited resources (see Litz et al., 2002; Litz & Bryant, 2009). Indicated prevention only targets individuals with significant and impairing grief symptoms who are at the greatest risk for enduring distress and dysfunction and PGD. Indeed, individuals at significant risk for PGD can be reliably identified in the first few months following loss. For example, in a study of caregivers of terminally ill patients, severe PGD symptoms three months prior to the death predicted PGD six months following the loss (Lichtenthal et al., 2011). Prigerson et al. (2009) also demonstrated that grief severity prior to six months following bereavement predicted morbidity at 6 to 12 and 12 to 24 months after bereavement. Similarly, high levels of psychiatric morbidity and aversive emotions are predictive of a more protracted course of grief reactions (Bonanno et al., 2005; Coifman et al., 2010). This convergent evidence shows that severe grief reactions that will not abate with time are detectable early on. In spite of this, to date, there are no indicated prevention programs for early PGD symptoms and impairment.

To address the need to target PGD in an indicated preventive framework, we developed and pilot tested an Internet-based therapist-assisted indicated prevention intervention called Healthy Experiences After Loss (HEAL). Internet-based interventions are scalable, cost-effective, and avoid draining scarce specialty care resources. The Internet also obviates barriers to seeking and receiving care (e.g., shame, stigma, logistical challenges such as impaired mobility and time constraints; Rochlen, Zack, and Speyer, 2004) that may be particularly relevant to older adults, the vast majority of bereaved individuals in the US (e.g., Hoyert, Kung, & Smith, 2005).Additionally, individuals who use technology to maintain connectedness have shown increased energy levels and quality of life following bereavement (Vanderwerker & Prigerson, 2004) suggesting that this may be a medium particularly well-suited for addressing PGD. The efficacy of Internet-based interventions for prolonged grief problems has recently been explored with encouraging initial findings (Kersting et al., 2013; Kersting, Kroker, Schlicht, Baust, & Wagner, 2011; Van der Houwen, Schut, van den Bout, Stroebe, & Stroebe, 2010; Wagner & Maercker, 2008; Wagner, Knaevelsrud, & Maercker, 2006) suggesting that the Internet is indeed a promising medium for the delivery of care in a bereaved population.

HEAL employs cognitive and behavioral self-management strategies designed to ameliorate core prolonged grief symptoms, namely psychological, behavioral, and social disengagement from the present in favor of yearning for the deceased and focusing on the past. HEAL targets the common complaints that PGD sufferers describe about the difficulties of adjusting to life in the absence of the deceased. These challenges include impaired capacity for enjoyment and self-care, low productivity and difficulty engaging and finding meaning in work or leisure activities, and difficulties forming new emotional bonds and relationships (e.g., Boelen, van den Hout, & van den Bout, 2006). HEAL emphasizes reengagement in positive self-care and wellness activities and reattachment to social resources (see Stroebe, Abakoumkin, & Stroebe, 2010). HEAL builds upon our prior successful Internet-based therapist-assisted self-management approach to PTSD (Litz, Engel, Bryant, & Papa, 2007). In a similar vein, HEAL sessions and homework exercises are designed to be easily self-navigated, with little if any, need for professional assistance or intervention. However, as was the case in our earlier work, HEAL is therapist-assisted in that each participant receives an initial brief telephone call to introduce HEAL and provide logon information. In addition, the therapist contacts participants (via email or, if need be, telephone) who are not regularly logging on to help troubleshoot any obstacles to completing the intervention in a timely fashion. The primary goals are to promote and reinforce completion of assignments and to intervene in the event of a clinical crisis. The therapist contact in HEAL is supportive and limited - the therapist neither provides intervention content nor delivers feedback on specific assignments completed by the participants (in contrast to Wagner, Knaevelsrud, & Maercker, 2006; Wagner & Maercker, 2008; and Kersting et al., 2011; Kersting et al., 2013). In addition to the benefit of monitoring and addressing clinical considerations in the event of a downward course or crisis, therapist-assistance has been associated with improved outcomes (Andersson & Cuijpers, 2009; Spek et al., 2007) and increased compliance and retention in internet-based interventions (Newman, Szkodny, Llera, & Przeworski, 2011).

The HEAL research occurred in three phases. Phase 1 was a content and website development phase, which entailed an extensive literature review, consulting with bereavement experts, and informed by our prior Internet-based intervention experience. Phase 2 entailed a program evaluation of HEAL to validate and standardize the protocol using feedback from clinical experts in bereavement as well as input from bereaved family members. Phase 3, described here, was a pilot randomized waitlist-controlled trial to examine HEAL’s efficacy as well as its feasibility, acceptability and tolerability. We also aimed to examine the extent of professional oversight required and its impact on efficacy.

Method

Participants

This study was approved by the Internal Review Boards of the institutions affiliated with the study; participants provided verbal consent over the telephone and returned a signed consent form by mail. Participants were bereaved caregivers of recently deceased patients who had been treated at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts. Information about the study was distributed to family members as part of a routine informational mailing distributed by the hospital’s Department of Psychosocial Oncology and Palliative Care between three- and six-months post-loss. Although the evidence-based time criterion for a PGD diagnosis in the ICD-11 is 6 months post-loss, alternative formulations of clinically significant grief in the DSM-5 (Adjustment Disorder related to Bereavement and Persistent Complex Bereavement-related Disorder) require a year to pass for a diagnosis (as was the case with the criteria for complicated grief; Horowitz et al., 1997). As such, in order to make this preliminary proof-of-concept trial as inclusive as possible, our recruitment targeted participants between 31 and 6 months post-loss, but permitted some eligible participants who were within a year post-loss2.

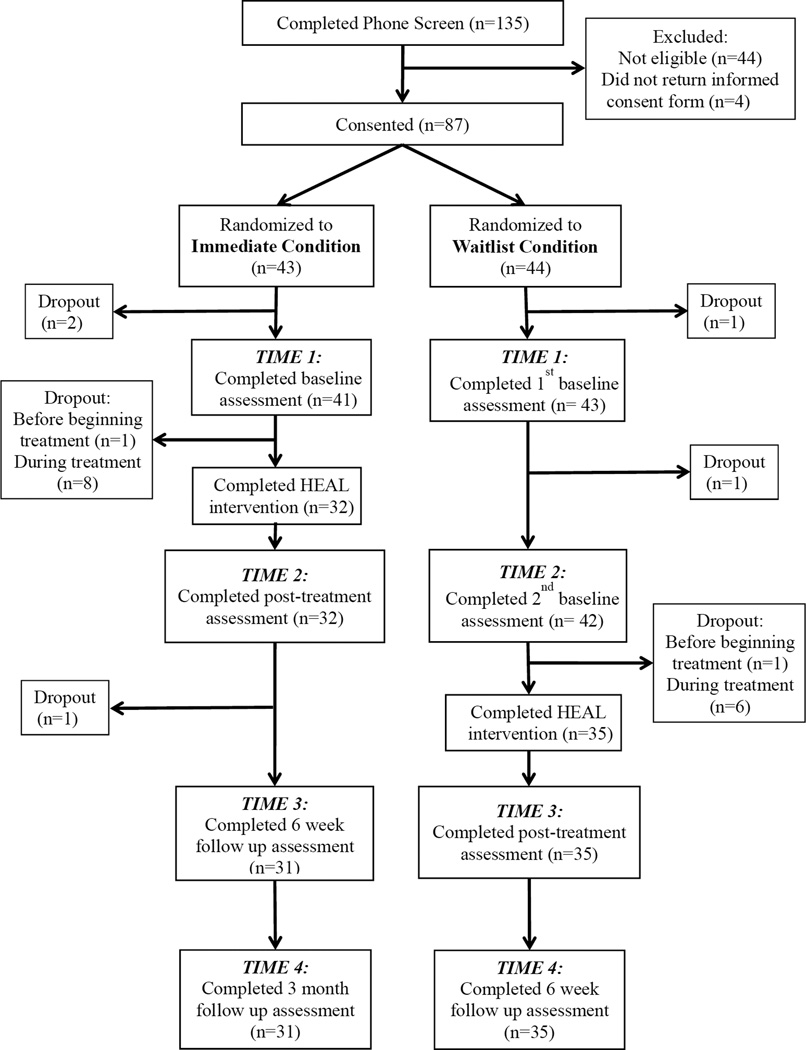

Participants were asked to contact study staff to either indicate interest in participating in the study or to opt out of study participation. Staff followed up with telephone calls to potential participants who neither responded to indicate interest nor to opt-out. One hundred and thirty five expressed interest in the study and were screened for eligibility by a doctoral candidate in psychology experienced in the administration of clinical assessments. All screening assessments were reviewed by a licensed clinical psychologist, and questionable cases were adjudicated by the principal investigators. Screening entailed phone administration of the Prolonged Grief Scale (PG-13; Prigerson et al., 2009), Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire (PDSQ; Zimmerman and Mattia, 2001), Alcohol Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT; Babor, Higgins-Biddle, Saunders, & Monteiro, 2001), Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST; Skinner, 1982), Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ; Hirschfeld, 2002) and the Revised Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996). Inclusion criteria consisted of: significant PGD symptoms (a score of 23 or higher) and functional impairment in social, occupational, or household responsibilities as indexed on the PG-13; Internet access; and a minimum age of 21 years. Exclusion criteria included conditions that might interfere with capacity to engage in the intervention (e.g., schizophrenia, delusional disorders, substance abuse or dependence in the last year); current suicidality (as indicated by a response of 2 or 3 on Item 9 of the BDI-II); current participation in bereavement support groups; or an inability to understand study procedures or participate in the informed consent process. Forty-four individuals were deemed ineligible based on these pre-established inclusion-exclusion criteria. A total of 87 individuals were randomized. Three individuals withdrew prior to baseline assessment. Three additional individuals withdrew prior to beginning the intervention and 14 withdrew during treatment. The demographic characteristics of the study group are provided in Table 1. Sixty-seven individuals (77.0% of enrollees, 82.7% of those who actually began treatment) completed HEAL (see Figure 1).

Table 1.

Demographics and Sample Characteristics

| Immediate (N=41) | Waitlist (N=43) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years ±SD | 56.17 ± 11.06 | 54.60 ± 9.60 |

| Time since loss, months ± SD | 8.42 ± 3.30 | 8.34 ± 2.65 |

| Gender, N (%) | ||

| Male | 12 (29.3%) | 15 (34.9%) |

| Female | 29 (70.7%) | 28 (65.1%) |

| Ethnicity, N (%) | ||

| Caucasian | 41 (100%) | 42 (97.7%) |

| Cuban American | 1 (2.4%) | 1 (2.3%) |

| Education, N (%) | ||

| Some High School | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.3%) |

| High School Diploma | 2 (4.9%) | 4 (9.3%) |

| Some College | 9 (22%) | 6 (14%) |

| Associates Degree | 3 (7.3%) | 2 (4.7%) |

| 4-year College Degree | 13 (31.7%) | 11 (25.6%) |

| Masters Degree | 14 (34.1%) | 13 (30.2%) |

| Doctoral Degree | 0 (0%) | 6 (14%) |

| Employment Status, N (%) | ||

| Full-time | 16 (39%) | 23 (53.5%) |

| Part-time | 6 (14.6%) | 3 (7%) |

| Unemployed | 4 (9.8%) | 7 (16.3%) |

| Disabled | 1 (2.4%) | 3 (7%) |

| Retired | 10 (24.4%) | 7 (16.3%) |

| Other | 4 (9.8%) | 0 (0%) |

| Current Income, N (%) | ||

| 0–$10,000 | 2 (4.9%) | 2 (4.7%) |

| $10,001–$25,000 | 3 (7.3%) | 6 (14%) |

| $25,001–$50,000 | 10 (24.4%) | 9 (20.9%) |

| $50,001–$75,000 | 11 (26.8%) | 10 (23.3%) |

| $75,001–$100,000 | 8 (19.5%) | 7 (16.3%) |

| $100,001–$125,000 | 2 (4.9%) | 2 (4.7%) |

| >$150,001 | 5 (12.2%) | 7 (16.3%) |

| Relationship with deceased, N (%) | ||

| Spouse | 29 (70.7%) | 35 (81.4%) |

| Partner | 3 (7.3%) | 2 (4.7%) |

| Child | 0 (0%) | 4 (9.3%) |

| Parent | 4 (9.8%) | 2 (4.7%) |

| Sibling | 2 (4.9%) | 0 (0%) |

| Relative | 2 (4.9%) | 0 (0%) |

| Friend | 1 (2.4%) | 0 (0%) |

| Primary caretaker of deceased, N (%) | ||

| Yes | 38 (92.7%) | 41 (95.3%) |

| No | 3 (7.3%) | 2 (4.7%) |

Figure 1.

CONSORT flowchart of participants through screening, enrollment, randomization, intervention, and assessments.

Study Design

This was a randomized waitlist controlled trial with rolling enrollment. Eligible participants who provided consent were randomized using a stratified block design (gender by race: White, African American, other) to an immediate treatment or waitlist condition. Participants in both groups completed an initial assessment. Individuals in the immediate treatment group were then provided with an Internet link to begin HEAL immediately, while participants in the waitlist group were informed that they would wait for six weeks and then complete a second assessment before beginning HEAL.

Participants in both groups were assessed four times. The immediate group was assessed prior to beginning HEAL (Time 1), upon completion of the intervention (Time 2; median = 19.37 weeks, range 8.13–60.03), followed by a follow-up assessment at approximately six weeks post-intervention (Time 3; median = 7.00 weeks, range 5.00–13.00) and another at three months post-intervention (Time 4; median = 14.00 weeks, range 11.00–17.00). Participants in the waitlist group were assessed upon entering the study (Time 1), before beginning HEAL (after a six week waiting interval, Time 2; median = 6.60 weeks, range 5.76–9.31), after completing the intervention (Time 3; median = 18.46 weeks, range 7.84–45.06), and approximately six weeks post-intervention (Time 4; median = 6.00 weeks, range 5.00–11.00). Aside from an initial telephone screening for eligibility and informed consent, all assessments were conducted online via a secure website. Online assessments were utilized because they are both cost- and time-efficient and simulate the ultimate intended use of HEAL as an Internet-based intervention.

Assessment Measures

At Time 1, we collected demographic information about age, gender, education, ethnicity, employment, income, the relationship with deceased, and the time since the loss. The primary outcome measure, administered at all four time points, was the 13-item Prolonged Grief Inventory (PG-13; Prigerson et al., 2009). The PG-13 assesses the extent and severity of PGD symptoms (e.g., yearning for the deceased, feelings of emotional numbness/detachment from others, feeling that a part of oneself died along with the deceased). The PG-13 is a subset of items from the Inventory of Complicated Grief (ICG: Prigerson et al., 1995). The ICG has very good internal consistency (α=.85), test-retest reliability (.80), and has excellent incremental validity in predicting a variety of grief-related functional impairments, controlling for depression and anxiety. The PG-13 was derived from an Item Response Theory analysis of the ICG, whereby its most informative and unbiased items were identified. Combinatoric analyses then determined the diagnostic algorithm providing the greatest degree of diagnostic efficiency with respect to the criterion standard (Prigerson et al., 2009). Thus, the PG-13 provides criteria for identifying individuals qualifying for a diagnosis of PGD. The PG-13 was also administered at the beginning of every HEAL session to track participants’ symptoms since their last session, to provide feedback about their session-by-session progress (each PG-13 score was added to a graph that was displayed for participants at each session), and to alert staff to any significant symptom exacerbation. In the present study, coefficient alpha for the PG-13 ranged from .83–.93, depending on the time point it was measured.

At each of the four time-points, we also assessed comorbid difficulties and functional impairments commonly associated with PGD. To track depression symptoms, we used the Revised Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II), a 21-item scale with well-established psychometric properties (α = .84 – .90; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996). To measure arousal and anxiety symptoms, we used the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), also a 21-item scale with well-known reliability and construct validity (α =.86 – .93; Beck, Epstein, Brown, & Steer, 1988). Because some losses could be conceptualized as traumatic events, we used the civilian version of the PTSD Checklist (PCL-C), a 17-item scale that assesses posttraumatic stress disorder with good psychometric properties (α=.86–.93; Weathers, Litz, Huska, & Keane, 1994). Finally, to evaluate drug and alcohol misuse, we used the 10–item Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST; Skinner, 1982) and the 10-item Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (α=.59–.64; AUDIT; Babor, Higgins-Biddle, Saunders, & Monteiro, 2001), each with very good psychometric properties.

As stated, in this trial, we also evaluated the acceptability and feasibility of HEAL. We used two measures to evaluate the participants’ impressions of and satisfaction with HEAL. We used the System Usefulness and Information Quality subscales of the Post-Study System Usability Questionnaire (PSSUQ) designed to evaluate system usability (Fruhling & Lee, 2005), which consisted of 13 items scored on a 7-point Likert-type scale. The System Usefulness score (α = .98) reflects the ease, simplicity, and efficiency of learning to use the website and using the website to effectively complete the desired tasks. The Information Quality subscore (α = .98) indicates the degree to which the information provided for using the website was clear, easy to understand, and effective for helping participants to complete the required tasks. We also administered a rationally derived Protocol Evaluation Questionnaire to assess participants’ ratings of the personal relevance and meaningfulness of the various HEAL modules, the accessibility of the information in the way it was conveyed online, and general reactions to the intervention and its web-based format. As part of this questionnaire, participants were also asked to provide qualitative feedback on each major component of the HEAL program, as well as the program overall.

Finally, the therapist carefully logged emails and telephone calls. We were interested in examining the relative time required for the oversight of HEAL and to examine if therapist time affected the results.

HEAL Intervention

HEAL is a cognitive-behavioral therapist-assisted Internet-delivered intervention designed to provide bereaved individuals with psycho-education about loss and grief and guide users in the use of strategies to reduce the distress and dysfunction associated with PGD. In contrast to previous Internet-based interventions for bereavement (Kersting et al., 2013; Kersting et al., 2011; Van der Houwen, et al., 2010; Wagner & Maercker, 2008; Wagner, Knaevelsrud, & Maercker, 2006) chiefly modeled on Interapy, an Internet-based intervention for posttraumatic stress and pathological grief (Lange et al., 2000), HEAL does not include formal exposure or cognitive reappraisal components. Rather, HEAL emphasizes: reengaging in self-care and wellness activities through self-monitoring and activity scheduling, re-establishing attachments with others in the aftermath of loss, and personal goal setting and achievement. HEAL sessions serve as a platform for introducing skills and strategies to be implemented off-line in-vivo between on-line sessions. The program consists of the following five sets of materials and modules presented over the course of 18 online sessions: (1) education about loss and grief (available at each online session), (2) instruction on stress management and other coping skills (available at all sessions), (3) behavioral activation in the form of homework assignments focused on self-care (sessions 2–8) and social re-engagement (sessions 9–17), (4) accommodation of loss by establishing and working toward a personalized list of goals (sessions 6, 8, 11, 14, & 17), and (5) relapse prevention/planning for the long-term (sessions 16–18). Each session required approximately 20 minutes to review the material, complete any in-session assignment, and/or report on the previous session’s homework. Additional time was required outside of session to complete the behavioral activation homework assignment. The time required to complete those assignments varied by user and session since the activities were self-selected by the participant.

Participants were encouraged to log on to the website three times per week in order to complete the 18 sessions of HEAL in approximately 6 weeks. Because this was a pilot trial, we wanted to learn as much as possible about ad lib usage. Consequently, users were permitted to proceed at a pace chosen by them. This user-directed approach allowed us to learn about variability in styles of engaging with the intervention content and homework assignments in order to refine the program for future iterations (e.g., provide more time to complete assignments, lessen homework burden, and so forth). We also reasoned that this approach would maximize participation and help avoid dropouts common to web-based interventions that lack the social demands for attendance and compliance inherent in face-to-face clinical trials and practice.

As a therapist-assisted self-management intervention (see Litz et al., 2007), HEAL required that participants’ progress was monitored by a study therapist, a clinical psychologist with expertise in grief counseling. HEAL has a specialized back-end that makes monitoring progress and homework compliance easy. The therapist was trained not to provide content or grief counseling. The therapist contacted each participant with a single phone call at the beginning of the intervention. This contact was intended to promote engagement and increase motivation for change. Each participant was also offered a phone call upon completion of the intervention as an opportunity to provide feedback on their experience. During the intervention, the therapist periodically corresponded with participants via brief emails to acknowledge notable progress, inquire about inactivity (failure to logon after long intervals, as noted above), or with a phone call to assess safety when a participant indicated significant distress (a score of 7 or above, where 1=”not at all” and 10 = “severe/incapacitating” in response to a question about “how hopeless [the participant has] felt in the last 24 hours” on their session check-in assessment). Participants were also able to initiate contact with the therapist as needed through the website by clicking on a link that would notify the study therapist that the participant wished to be contacted. Therapist interactions with participants were designed to be supportive but brief (e.g., emails limited to a few sentences and phone calls on average less than 10 minutes), in order to maximize the likelihood that the primary source of intervention would stem from the Internet protocol itself.

Results

Participant Characteristics

The randomized and treated sample (N = 84: nimmediate = 41, nwaitlist = 43) consisted of 27 (32%) men and 57 (68%) women. On average, participants were 55.37 years of age (SD=10.30 years), reported that they had known the deceased for 32.31 years (SD = 15.30 years), and 78% were the diseased patient’s spouse/partner. At the time of the first assessment (Time 1), average time since loss was 8.38 months (SD=2.97 months). On baseline measures of alcohol use, scores on the AUDIT were well below the cut-off score of 8 for hazardous or harmful drinking (M=3.01, SD=2.56). Scores on the DAST were similarly negligible (M=.16, SD=.43), falling well below a score of 1, which would indicate a low level of drug use. Due to low base-rates and floor effects seen on the AUDIT and DAST at baseline, further analyses were not performed on these measures.

Randomization Check

We conducted independent sample t-tests, correlations, or one-way ANOVAs (where appropriate) on Time 1 PG-13, BDI, PCL, and BAI scores, demographic variables, relationship to deceased, and time since loss. No significant differences were found between conditions on any of these variables (ps >.56) with the exception of the BAI. Scores on the BAI in the immediate group were higher (M=35.38, SD=11.16) than in the waitlist group (M =34.47, SD =7.52), although this difference was only marginally significantly different, t(81) =.19, p =.06.

Despite the equivalence of the groups at randomization, there was one important difference between the groups. Unexpectedly, participants took substantially longer than 6 weeks to complete the HEAL intervention. The mean time to complete HEAL for participants in the immediate group was 24.15 weeks (SD=13.92). Because the waitlist interval was fixed at 6 weeks, the time interval between the two conditions was not equivalent, complicating the comparison between the two groups. Consequently, prior to comparing these two groups, we took a number of steps to examine the potential impact time may have had on these comparisons. First, we examined the within-group correlations between time and outcome (as well as the plots of time versus outcome). Within-group correlations between time and outcome variables (adjusting for Time 1 scores) were all non-significant (ps >.16), and the plots did not suggest nonlinearity. To further bolster confidence that the time it took to complete HEAL was not a confounding variable, we also conducted analyses using the session-by-session PG-13 score that most closely corresponded to 6-weeks since beginning the program as the Time 2 score for the immediate group. This allowed us to compare the effects of time and condition using comparable data across the two groups. These findings are reported together with the primary analyses described below.

Time Since Loss

Because there are discordant opinions about the required amount of time since loss required to diagnose PGD and the role of time in the resolution of symptoms, we examined the potential impact of time since loss on the primary and secondary outcome variables prior to conducting the main analyses. Partial correlations between time since loss and Time 2 (post-treatment for the immediate group, post-6-week waiting period for the waitlist group) outcomes scores were all non-significant (ps >.21). We also examined the correlations between time since loss and both pre- and post-treatment scores (collapsed across conditions). Again, all correlations were non-significant (ps >.17). Given these non-significant correlations, time since loss alone cannot account for changes that may be observed between pre-treatment and post-treatment.

Intent-to-treat Analysis

To examine whether participants in HEAL evidenced significant symptom improvement over their counterparts on a 6-week waiting list, we conducted an intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis. We used linear mixed models (LMM) with restricted maximum likelihood (REML) estimation in order to take advantage of all available data at each time point. Condition, time, and the condition by time interaction were entered in each model; education and income were included as covariates. Analyses were conducted on PG-13 scores (primary outcome) as well as BDI, PCL and BAI scores. Controlled between group effect sizes were calculated as a Cohen’s d, subtracting the mean change from Time 1 to Time 2 for the waitlist group from the mean change in the immediate group, and dividing by the pooled Time 1 standard deviations (Morris, 2008).

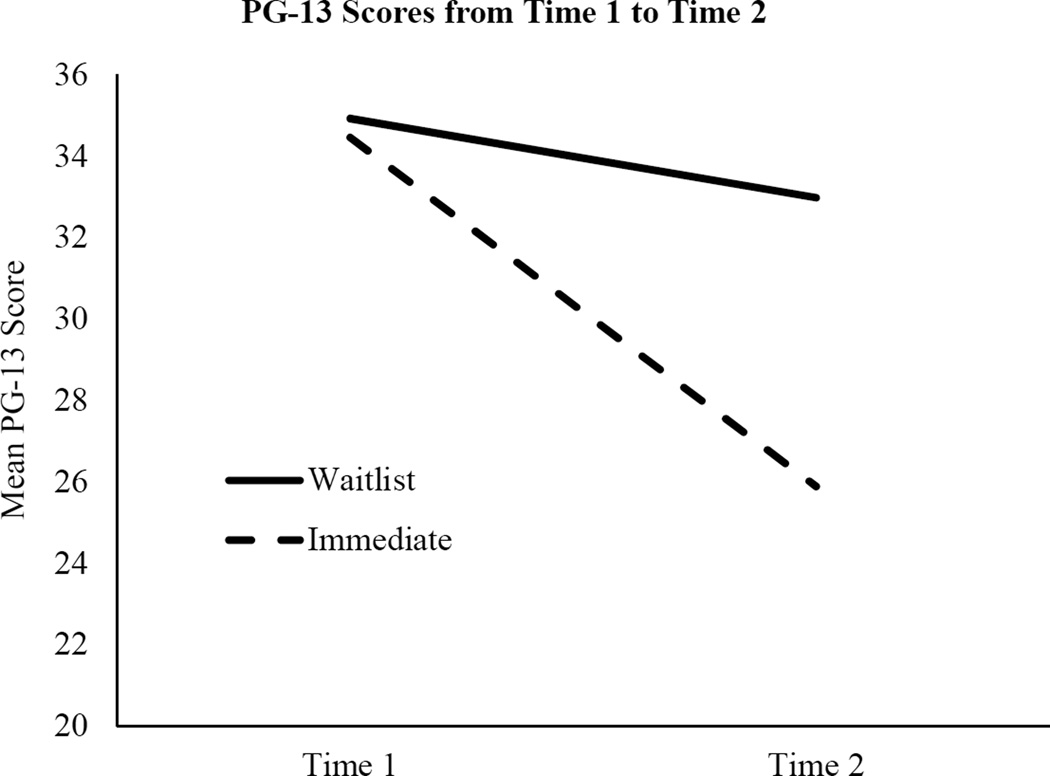

HEAL resulted in significant reductions in PG-13 symptoms from Time 1 to Time 2 in the immediate treatment group compared to the waitlist group (Figure 2 shows a graphic representation of the condition by time interaction for PG-13 scores). The condition by time interaction was also significant for each secondary outcome variable. That is, HEAL also resulted in significant reductions in depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress symptoms from Time 1 to Time 2 compared to the waitlist group. Table 2 shows the means by condition for the primary and secondary outcome variables, the F-statistic for each interaction, and the between-group effect sizes. Importantly, substituting the 6-week PG-13 session-by-session data for Time 2 scores for the immediate group yielded the same statistically significant interaction F(1, 78.15= 15.29, p <.001) as when the post-intervention score was used as the second time point. Notably, after 6 weeks in the HEAL program, on average, PG-13 scores dropped 7.29 points, while scores for the waitlist group dropped only 2.11 points (t (78.15) = −3.91, p <.001).

Figure 2.

Change in prolonged grief symptom severity attributable to treatment. PG-13=Prolonged Grief Inventory.

Table 2.

Efficacy of HEAL: Immediate versus Waitlist Comparisons

| Time 1 | Time 2 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Waitlist | Immediate | Waitlist | Immediate | |||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | Time X Condition | d [95%CI] | |

| PG-13 | 34.99 | 7.46 | 34.39 | 8.11 | 32.84 | 9.11 | 24.70 | 8.33 | F(1, 74.10) = 29.04** | 1.10 [.63, 2.27] |

| BDI | 37.65 | 8.01 | 38.08 | 8.20 | 36.15 | 8.67 | 30.80 | 7.60 | F(1, 72.63) = 14.19** | .71 [.27, 1.15] |

| PCL | 38.33 | 11.28 | 39.73 | 11.99 | 37.31 | 12.74 | 28.11 | 10.06 | F(1,71.87) = 27.68** | .91 [.46, 1.36] |

| BAI | 31.52 | 7.52 | 35.22 | 11.16 | 30.31 | 6.78 | 29.18 | 9.39 | F(1,73.99) = 10.68* | .51 [.07, 94] |

Note.

p<.01.

p<.001.

PG-13=Prolonged Grief Inventory; BDI=Beck Depression Inventory; PCL=Posttraumatic Checklist; BAI=Beck Anxiety Inventory.

Clinical significance

We used two methods to explore clinical significance. First, we conducted chi-square tests comparing the number of participants in each group who met criteria for PGD at Time 1 to those meeting criteria at Time 2. PGD caseness was defined in the following manner: (1) significant separation distress (i.e., feelings of longing, pangs of grief) experienced at least once a day over the past month, and (2) at least five additional cognitive, emotional, and behavioral symptoms (e.g., confusion about one’s role in life; difficulty accepting the loss; avoidance, distrust, bitterness, or emotional numbing related to the loss) rated as “quite a bit” or “overwhelmingly” over the past month. Analyses suggested no significant differences between the immediate treatment and waitlist groups in the number of participants meeting criteria for PGD at Time 1 (χ2 =1.19, p =.28, nimmediate = 15 (37%), nwaitlist = 11 (26%)). However, there was a significant difference between conditions at Time 2, (χ2 = 4.12, p =.04); after completing HEAL, only two participants (6%) in the immediate treatment group continued to meet criteria for PGD, compared to 10 (24%) in the waitlist condition. Second, we explored clinical significance by following the procedures outlined by Jacobson and Truax (1991). Because norms on the PG-13 for a functionally normal population are not yet available, we used the more conservative CS cut-off of two standard deviations (in the functional direction) from the pre-treatment mean of the immediate group (CS cut-off = 19.22). To calculate the reliable change index (RCI), we estimated the test-retest reliability of PG-13 using scores from the first and third sessions of HEAL (approximately 1–2 weeks apart, on average; α = .86), and used the formula presented by Jacobson and Truax (1991; pg. 14). We then used the following classification scheme to estimate clinical change. Participants were deemed: (1) recovered if they passed CS and RCI criteria; (2) improved if they passed RCI only; (3) unchanged if they did not pass CS or RCI; or (4) deteriorated if they passed RCI in negative direction. Based on this conservative scheme, in the immediate group, 8 participants were classified as recovered, 11 were classified as improved, 12 were unchanged, and one participant deteriorated. In contrast, only 1 participant was classified as recovered in the waitlist condition, with 5 improving, 34 remaining unchanged, and 2 deteriorating.

Pooled Study Findings

To examine the overall impact of HEAL over time, we pooled ITT data across conditions and used LMM with REML to compare pre-intervention scores to post-intervention, 6-week follow-up, and 3-month follow-up scores (immediate group only; Time 4 assessment for waitlist group was conducted at 6 weeks). Controlled within-group effect sizes were calculated as Cohen’s ds by dividing the mean difference between pre-intervention scores and each follow-up score by the appropriate pooled standard deviation. Table 3 contains the means, standard deviations, t-tests for comparisons to pre- intervention scores, and within group effect sizes for the outcome variables for all participants prior to beginning HEAL, upon completing HEAL, 6 weeks later, and 3 months later for the immediate group. Compared to pre-intervention scores, HEAL resulted in significant reductions to PG-13, BDI, PCL, and BAI scores at each follow-up assessment, ps<.02.

Table 3.

Efficacy of Heal: Pooled Groups Over Time

| Pre-intervention | Post Inter-vention | 6-week follow-up | 3-month follow-up* | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | t(df) | d [95% CI] | M | SD | t(df) | d [95% CI] | M | SD | t(df) | d [95% CI] | |

| PG-13 | 33.52 | 8.42 | 24.08 | 8.70 | t(68.86) = −10.14 | 1.10 [.81,1.39] | 23.35 | 8.09 | t(70.44) = −10.85 | 1.23 [.92, 1.54] | 23.07 | 8.04 | t(67.86) = −11.12 | 1.24 [.79, 1.74] |

| BDI | 36.95 | 8.07 | 30.52 | 6.99 | t(74.21) = −7.51 | 0.85 [.58,1.12] | 30.15 | 6.99 | t(75.77)= −7.45 | 0.90 [.60, 1.19] | 30.42 | 7.72 | t(71.48) = −6.40 | 0.83 [.37, 1.27] |

| PCL | 38.27 | 11.97 | 28.31 | 9.58 | t(74.53) = −9.02 | .92 [.66, 1.17] | 27.37 | 9.92 | t(74.94) = −9.37 | 0.99 [.71, 1.26] | 27.84 | 9.88 | t(69.19) = −8.26 | [.52, 1.37] |

| BAI | 32.68 | 9.50 | 28.47 | 8.52 | t(72.61) = −4.90 | 0.47 [.26, .67] | 27.24 | 7.63 | t(73.67) = −5.91 | 0.63 [.39, .87] | 27.85 | 8.81 | t(67.40) = −4.55 | .95 0.53 [.20,.85] |

Immediate group only.

T-statistic is derived from the fixed effects estimates of the LMM. PG-13 = Prolonged Grief Inventory; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; PCL = Posttraumatic Checklist; BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory.

Clinical significance

To further examine the clinical significance of these findings over time, we first conducted chi-square tests comparing the number of participants who met criteria for PGD prior to starting HEAL to those meeting criteria at post-intervention, 6-week, and 3-month follow-ups (3-month data again was only available for immediate group). Upon completing HEAL, significantly fewer participants met criteria for PGD, and this reduction was maintained over time (ps <.004). Specifically, prior to receiving the intervention, 25 participants across both conditions (30.1%) met criteria for PGD. Upon completion of the intervention, only six (9.0%) continued to meet criteria for PGD (χ2 =10.13, p <.001), and that number was further reduced to five (7.6%) by the 6-week follow-up assessment (χ2 =11.62, p <.001). Among those assessed at 3 months (immediate group only), the number of participants meeting criteria for PGD was reduced from four at 6-week follow-up to two (6.5%) by the 3-month follow-up (χ2 =8.14, p =.004). Then, utilizing the conservative approach to Jacobson and Truax (1991) criteria described above, we found 19 participants were classified as recovered, 18 as improved, 28 as unchanged, and 2 as deteriorated at the post-test assessment. At the six week follow-up, 18 were classified as recovered, 23 as improved, 24 as unchanged, and 1 as deteriorated. At the three month follow-up (limited to those who were in the Immediate condition), 9 participants were classified as recovered, 13 as improved and 9 as unchanged (no participants were classified as deteriorated).

Therapist Contact

Overall, most participants had minimal contact with the study therapist and primarily used the website to guide them through the intervention. The average number of therapist-initiated phone calls was considerably less than one per week (.24; SD =0.26, range =0 – 1.91), roughly once every four weeks, for each participant during the intervention-phase. These calls included the initial welcome/orientation call, final feedback call, and calls made in response to user alerts or online requests for assistance. Calls typically ranged from 2 to 10 minutes. During the intervention, the study therapist also initiated an average of .60 emails per week/per participant (SD =0.38, range = 0.27 – 3.10) and left an average of .15 voicemails per week/per participant (SD =.20, range = 0 – 1.27). Emails consisted primarily of minor logistical or administrative contacts, brief acknowledgments of progress on homework assignments, or prompts to logon to the website after periods of inactivity. There were no significant differences between the average number of telephone calls or emails sent from the study therapist per group (waitlist vs. immediate start).

We examined whether each type of therapist contact, average number of contact per week, and total number of contact were related to the outcome variables, controlling for pre-intervention scores. Although there were several significant correlations (and several approaching significance), these correlations were all positive, suggesting that increased therapist contact was associated with greater symptomatology rather than improvements in outcome (see Table 4). This is not surprising given that much of the therapist contact was initiated in response to high symptom self-report by the participant.

Table 4.

Correlations between Therapist Contact and Outcome Variables Controlling for Time 1 Scores-- All Participants Completing HEAL

| Time 2 Score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PG-13 | BDI | PCL | BAI | |

| Emails | −.077 | −.085 | .004 | .069 |

| Voicemails | .241* | .218† | .206 | .315* |

| Telephone calls | .225† | .231† | .220† | .104 |

| Average emails per week | −.017 | .071 | .000 | −.107 |

| Average voicemails per week | .221† | .159 | .167 | .155 |

| Average phone calls per week | .312* | .266* | .230† | −.020 |

| Total therapist contact | .084 | .075 | .131 | .182 |

| Average weekly therapist contact | .228† | .227† | .173 | −.008 |

Note.

p<.05.

p<.08. Correlations were run separately for each outcome variable and controlled for Time 1 scores.

Participant Feedback and Experience

All participants who completed HEAL (N=67) provided feedback about their experience of the intervention and website as well as the perceived quality of the intervention content. On the Protocol Evaluation Questionnaire, the vast majority reported a “somewhat positive” (44.8%) to “extremely positive” (43.3%) reaction to the website. Only two participants endorsed “somewhat negative” (1.5%) and “extremely negative” (1.5%) reactions. Most users endorsed the idea of using a website to help with grief problems as “quite a bit appealing” (46.3%) or “extremely appealing” (32.8%), whereas a minority found it “just acceptable” (14.9%), “somewhat unappealing” (4.5%), or “extremely unappealing” (1.5%). The ease with which participants were able to move around the website was rated as “extremely easy” (58.2%), “moderately easy” (34.3%), and “moderately difficult” (7.5%).

The PSSUQ subscale scores were consistent with these findings. Each PSSUQ item is rated from one to seven, the latter indicating a strongly negative reaction. The mean System Usefulness subscore for all participants was 3.02 (SD =2.16), which indicates that users found it fairly easy and efficient to learn to navigate the website and use it to complete tasks. Similarly, the mean Information Quality subscore was 2.95 (SD =2.06), suggesting that participants mostly found the information about how to use the website to be clear and easy to follow. There were no significant differences on the PSSUQ between the immediate treatment and waitlist groups. Participant feedback about the value of the information and activities provided in HEAL was also very positive. Based on the Protocol Evaluation Questionnaire, participants found the content of HEAL to be logical (M =7.16 out of 9.0, SD =1.7). Most (77.6%) participants reported that the HEAL program provided “just the right amount” of information, while 16.4% would have preferred more information, and 6.0% thought there was “somewhat too much” information. Further, 77.6% rated that the instruction level on HEAL “just right” while a smaller percentage found it “somewhat too basic” (20.9%) or “far too basic” (1.5%). Participants were largely satisfied with the content of the program, with most participants reporting that they learned a “moderate” (53.7%) or “large” amount (35.8%) from the program. Further, when asked how interesting they found the content, 43.3% responded that it was “extremely interesting,” and another 53.7% rated it as “somewhat interesting.” Overall, over 90% consistently rated the individual components of HEAL as “moderately” to “extremely” valuable. Participants also reported they would be “quite confident” in recommending HEAL to a friend experiencing similar problems (M =7.37 out of 9.0, SD =1.89).

Completers Versus Non-Completers

We also were interested in examining factors potentially related to participants’ failure to complete the intervention. On average, participants who did not complete HEAL spent 12.18 weeks (SD =9.56) in the program and completed a mean of 4.06 sessions (SD = 3.26). There were no differences between completers and non-completers on any of the demographic variables, pre-intervention outcome measures (PG-13, BDI, PCL, BAI), or average weekly therapist contact while in the program (ps >.11), with two exceptions. Non-completers received more average weekly email (M =.96, SD = .76) from the therapist while in the program compared to completers (M =.53, SD =.18), although this difference was only marginally significant (t(12.26) = 1.97, p =.07) and not unexpected due to the fact that infrequent logins prompted therapist contact. The other difference was in employment status as reported at Time 1. A larger percentage (58.8%) of non-completers were employed full-time than completers (43.3%; χ2 =12.22, p =.032). This suggests that competing commitments in the work place may have made it difficult for some participants to engage in the program.

Discussion

The goal of this trial was to assess the efficacy, feasibility, acceptability, and tolerability of an Internet-delivered indicated prevention intervention for PGD. The results suggest that HEAL is a promising indicated prevention approach that reduces bereavement-related difficulties and prevents PGD. Controlled effect sizes comparing the immediate treatment to the waitlist group revealed that HEAL was also associated with significant and clinically meaningful reductions in PGD, PTSD, depression, and anxiety. Moreover, these gains were maintained over time. In addition, participation in HEAL led to noteworthy reductions in the prevalence of PGD.

In addition to a large treatment response, most participants reported high levels of satisfaction with the content of HEAL and the homework assignments. Most rated their experience using HEAL to be “somewhat” to “extremely” positive; use of an Internet intervention for grief as “quite a bit” to “extremely” appealing; the Internet interface as being “moderately” to “extremely” easy to use; the amount of information, level of instruction, and amount learned as “positive;” and their overall experience as “moderately” to “extremely” valuable. In terms of acceptability and tolerability, dropout rates (23% of those randomized to HEAL, 17.3% of those who completed at least one session) were comparable to other Internet-delivered treatments for mental health problems (Newman et al., 2011; Melville, Casey, & Kavanagh, 2010; Spek et al., 2007) and trials of behavioral activation of depression (Cuijpers, van Straten & Warmerdam, 2007). In comparison to other interventions specifically targeting grief, the dropout rate for those who began the treatment was somewhat higher than in Wagner, Knaevelsturd, and Maercker (2006; 8%) and Kersting et al. (2013; 14%), but was somewhat lower than Kersting et al. (2011; 24%) and much lower than van der Houwen et al. (2010; 52%). It is also lower than rates seen in face-to-face treatments for PGD. For example, 27% of those who began treatment dropped out in Shear et al. (2005)’s Complicated Grief Therapy, and in Boelen, de Keijser, van den Hout, and van den Bout (2007), 26% of those who began active treatment and 36% of those in a supportive counseling control group dropped out.

Nevertheless, further development of the HEAL protocol and procedures is necessary. The intervention took considerably more time to complete, and individual sessions required more logons than anticipated. The latter will require improving the software to allow greater flexibility of session usage. However, given the efficacy of the intervention, the trial results suggest that adding more content and requiring more sessions is not necessary. It appears that we should consider relaxing the time requirement in the next iteration of HEAL. For example, we could require one logon per week, keep the same content and homework assignments, but lengthen the intervention to 18 weeks. Although speculative, it could be that the reengagement and reattachment behavioral activation elements require more time to problem-solve and implement. Another possible strategy to improve temporal adherence would be to establish deadlines a priori for the completion of assignments, which may motivate steady engagement with the material (Andersson, Carlbring, Ljotsson, & Hedman, 2013). In this context, we could also build in automatic email reminders prompting regular logging in. In contrast, another alternative, would be to give users ad-lib access to HEAL exercises and materials allowing users to proceed at their own pace with no time restriction, however it would be important to incorporate reminders and other forms of reinforcement and encouragement to counteract poor adherence and outcomes that typically characterize “open-access” internet interventions (see Christensen, Griffiths, and Farrer, 2009).

This study had a number of limitations. First, the sample consisted of a relatively homogeneous group of mainly Caucasian, well-educated individuals, the majority of whom were grieving the loss of a spouse. To avoid Type II error for the pilot study, this was an important population to investigate as it is represents a group at high risk for PGD and related morbidity, especially in the elderly (Maciejewski et al., 2007). However, future research will need to explore the generalizability of these findings to other bereaved populations. Second, while the accessibility and scalability of the online self-report measures complemented the Internet-based nature of HEAL, blinded independent clinical evaluation of the main outcomes might have reduced self-report biases that could have inflated treatment effect size estimates. However, preliminary evidence suggests that online assessments may actually reduce demand characteristics to show gains from therapy, in contrast to face-to-face assessment, which may encourage under-reporting of symptoms, due to fear of stigma or disappointing earnest study staff and allegiance effects (e.g., Gribble et al., 2000). Additionally, it is important to note that the equivalency of paper-and-pencil and on-line versions of our measures have not been sufficiently examined. Although research examining the comparability of these two methods of administration has yielded mixed results, recent research suggests that when methodological consideration are held constant (e.g., recruitment strategies, administration methodologies) online versions of reliable and validated measures are equal psychometrically to more traditional paper and pencil versions (Weigold, Weigold, and Russell, 2013). Nonetheless, it is possible that the context of completing these measures online may have influenced participant responses in undetermined ways. Future endeavors to validate these and other measures across administration methodologies would constitute an important contribution to the field, in light of the ever increasing frequency with which on-line assessment is likely to be utilized given its many functional advantages (e.g., ease of administration, ability to prevent missed items, relative ease of data input, etc.). A third and important limitation is that because, on average, participants required more time to complete HEAL than expected, the utility of the waitlist control design was limited. Although waitlist designs unmatched on time have been used before in clinical research (e.g., Bergman, Gonzalez, Piacentini, & Keller, 2013; Kendall, 1994), it introduces the potential for time to act as a confound. We are particularly sensitive to this concern in the case of grief, which in its normative presentation tends to remit over time. However, two pieces of evidence indicate that time was not a confounding variable in this study: the fact that time since loss was uncorrelated with any outcomes, and the co-incident session-by-session PG-13 at 6-weeks indicated that at 6 weeks into HEAL participants were already reporting improved symptoms over waitlist participants, together strongly suggest that time was not a confounding variable in this study. Importantly, our waitlist design showed that for those on the waitlist, grief symptoms did not significantly change during the 6-week waiting interval, providing evidence that pre-clinical but significant grief symptoms and impairment do not simply abate with time. In the next phase of our research on HEAL, we will examine HEAL in a context in which time is controlled in order to rule out this concern more definitively. Furthermore, we will follow participants for a longer duration in order to develop a more comprehensive understanding of the impact of HEAL over time. Finally, because we accepted some individuals into the trial who met the ICD-11 time-since-loss criterion for a diagnosis of PGD (6-months), it could be argued that in some cases, HEAL was not acting as an indicated prevention, but rather a treatment for PGD (albeit early on). However, even if the 6-month criterion were a perfect boundary between pre-clinical problems and mental illness, in cases that cross this time threshold (but still prior to one year), we would argue that we were preventing chronic grief-related disability. In addition, it should be underscored that the mean time since loss in our trial was considerably shorter than Wagner et al.’s (2006) and van der Houwen et al. (2010)’s Internet-based treatment studies (M=4.6 years and M= 3.37 years, respectively) and Shear et al.’s (2005) treatment trial (M=2.5 years). Our approach was similar to Kersting et al. (2013; M=9.93 months), Kersting et al. (2011; M= 15.4 months) and Wagner et al. (2008; M- =7.1 months), however these studies were not formally indicated preventions.

Despite these limitations, these preliminary results suggest that an indicated prevention program specifically screening for PGD symptoms has the potential to limit the long-term mental health effects of unresolved grief without iatrogenic effects. The latter is a significant concern given that broad-based selective preventions and other studies with inadequate screening may interfere with natural healing processes associated with bereavement (Currier, Neimeyer, & Berman, 2008) leading the authors of a recent meta-analysis to suggest that preventive interventions “do not appear to be effective” and conclude that “complicated grief can be treated, but not prevented” (Wittouck, et al., 2011). Our results suggest that when used as an indicated prevention, HEAL has the potential to be an effective, well-tolerated tool to reduce the burden of loss on survivors most at risk for subsequent mental and physical health difficulties. The reductions across symptom clusters found in this study are consistent with treatments targeting post-loss disengagement and avoidance via activities scheduling. This suggests that avoidance and disengagement may be transdiagnostic in the development of post-bereavement psychopathology (Acierno et al., 2012; Papa, Sewell, Garrison, & Rummel, in press). Moreover, these results were found with minimal professional supervision and, despite the fact that we intentionally engaged an experienced therapist with bereavement expertise to ensure the highest safety standards for this trial, we found that the role the therapist ultimately played in the trial required minimal specialized therapeutic training making this intervention highly scalable. This is especially critical given that there are no evidence-based secondary prevention programs for PGD nor adequate professional resources to address the general clinical need in this area (Genevro, et al., 2004). Internet-delivered therapies have the potential to reach large segments of the population that might not seek or have access to specialized care, a feature which is especially relevant to mass-casualty events impacting entire communities. They also provide a cost-effective solution for an under-addressed public health problem in medical and palliative care settings: the provision of bereavement services to caregivers after the patient has died.

In sum, our trial advances research on prolonged grief symptomatology in a number of important ways. First, in contrast to discouraging selective prevention findings (Wittouck et al., 2011), this trial suggests that PGD can be prevented in an indicated prevention framework. Second, prior investigations of Internet-based interventions for grief have relied upon exposure and cognitive reappraisal-based written exercises. Our study is unique in its focus on self-care, social reengagement and goal-focused activities. This format may appeal to a broader population and may save costs because it is ostensibly self-guided and requires very little specialty care time and effort. That said, the impact of having a therapist involved in the study should not be discounted. Rochlen et al. (2004) noted the potential benefit of “telepresence” associated with Internet-based interventions in which participants feel the presence of a therapist or professional without some of the distracting or superficial aspects of interaction that might be associated with face to face interactions. Furthermore, the single Internet-based grief treatment trial that included no therapist feedback (van der Houwen et al., 2010) reported much higher rates of attrition than those where feedback was incorporated as part of the intervention (Kersting et al. 2013, Kersting et al., 2011, Wagner & Maercker, 2008, Wagner, Knaevelsrund, Maecrker, 2006), suggesting that the presence of a therapist may assist in keeping participants engaged in treatment. Whether this is through their enhancement of the content, motivational encouragement, or simply the sense that there is another person invested in whether you continue in the treatment is not currently clear. Further research into the role of the therapist in HEAL is necessary to determine whether the role could be performed by a para-professional or whether it is even necessary at all. Additional research is also needed to refine the delivery protocols for HEAL and to assess its efficacy in a large-scale trial with an active control comparison condition. Thus, this trial constitutes only the first-step in what we hope will be important advances in the area of indicated preventive intervention for PGD that is broadly accessible, scalable, and cost-effective.

Research Highlights.

Healthy Experiences After Loss is a web-based prevention for prolonged grief

We examined efficacy, acceptability, and impact of professional oversight

84 patients with early prolonged grief entered the wait-list controlled pilot trial

HEAL led to large reductions in prolonged grief and lower incidence rates

Satisfaction and usability were high and professional oversight very low

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (MH079884) awarded to the Brett Litz.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Previous research demonstrates that attempts to recruit bereaved participants prior to 3 months are ineffective. Furthermore, hospital officials further raised concerns that premature contact with potential participants post-loss would be perceived as inappropriate and intrusive.

Five participants who were over a year post-loss requested access to the intervention. To maximize our opportunity to explore the preliminary efficacy of this intervention, they were permitted to participate. Upon analysis, time since loss was uncorrelated with all outcomes at all intervals and as such their data is included in the results reported here.

A score of at least 36 on the PG-13 is indicative of a probable clinical diagnosis of PGD. The range of PG-13 scores for screened subjects was 23-51, the median was 32, and the mode was 29 (the mean was 33.42).

Contributor Information

Brett T. Litz, VA Boston Healthcare System, Massachusetts Veterans Epidemiological Research and Information Center and Boston University School of Medicine

Yonit Schorr, VA Boston Healthcare System, Massachusetts Veterans Epidemiological Research and Information Center.

Eileen Delaney, Naval Center for Combat & Operational Stress Control - Bureau of Medicine and Surgery.

Teresa Au, Boston University.

Anthony Papa, University of Nevada at Reno.

Annie B. Fox, VA Boston Healthcare System

Sue Morris, Dana Farber Cancer Institute.

Angela Nickerson, University of New South Wales.

Susan Block, Dana Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard University School of Medicine.

Holly G. Prigerson, Weill Cornell Medical College

References

- Acierno R, Rheingold A, Amstadter A, Kurent J, Amella E, Resnick H, Lejuez C. Behavioral activation and therapeutic exposure for bereavement in older adults. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Care. 2012;29:13–25. doi: 10.1177/1049909111411471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G, Carlbring P, Ljotsson B, Hedman E. Guided Internet-based CBT for common mental disorders. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy. 2013;43:223–233. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G, Cuijpers P. Internet-based and other computerized psychological treatments for adult depression: A meta-analysis. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2009;38:196–205. doi: 10.1080/16506070903318960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guideline for use in primary care. 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes JB, Dickstein BD, Maguen S, Neria Y, Litz BT. The distinctiveness of prolonged grief and posttraumatic stress disorder in adults bereaved by the attacks of September 11th. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2012;136(3):366–369. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting And Clinical Psychology. 1988;56:893–897. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Boelen PA, Prigerson HG. The influence of symptoms of prolonged grief disorder, depression, and anxiety on quality of life among bereaved adults: A prospective study. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2007;257:444–452. doi: 10.1007/s00406-007-0744-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boelen PA, de Keijser J, van den Hout MA, van den Bout J. Treatment of complicated grief: A comparison between cognitive-behavioral therapy and supportive counseling. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:277–284. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boelen PA, van den Bout J. Complicated grief, depression, and anxiety as distinct postloss syndromes: A confirmatory factor analysis study. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162(11):2175–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.11.2175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boelen PA, van den Hout MA, van den Bout J. A cognitive-behavioral conceptualization of complicated grief. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2006;13:109–128. [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Moskowitz JT, Papa A, Folkman S. Resilience to loss in bereaved spouses, bereaved parents, and bereaved gay men. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;88:827–843. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.5.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Neria Y, Mancini A, Coifman KG, Litz B, Insel B. Is there more to complicated grief than depression and posttraumatic stress disorder? A test of incremental validity. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116(2):342–351. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.2.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Wortman CB, Lehman DR, Tweed RG, Haring M, Sonnega J, Nesse RM. Resilience to loss and chronic grief: A prospective study from preloss to 18-months postloss. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;83(5):1150. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.83.5.1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley T, Morel-Kopp MC, Ward C, Bartrop R, McKinley S, Mihailidou AS, Tofler G. Inflammatory and thrombotic changes in early bereavement: A prospective evaluation. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology. 2012;19:1145–1152. doi: 10.1177/1741826711421686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JH, Bierhals AJ, Prigerson HG, Kasl SV, Mazure CM, Jacobs S. Gender differences in the effects of bereavement-related psychological distress in health outcomes. Psychological Medicine. 1999;29:367–380. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798008137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen H, Griffiths KM, Farrer L. Adherence in Internet interventions for anxiety and depression: a systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2009;11(2) doi: 10.2196/jmir.1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coifman KG, Bonanno GA. When distress does not become depression: Emotion context sensitivity and adjustment to bereavement. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119:479–490. doi: 10.1037/a0020113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Warmerdam L. Behavioral activation treatments of depression: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2007;27:318–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currier JM, Neimeyer RA, Berman JS. The effectiveness of psychotherapeutic interventions for bereaved persons: A comprehensive quantitative review. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;134:648–661. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.5.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillen L, Fontaine JR, Verhofstadt-Denève L. Confirming the distinctiveness of complicated grief from depression and anxiety among adolescents. Death Studies. 2009;33:437–461. doi: 10.1080/07481180902805673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fruhling A, Lee S. Assessing the reliability, validity and adaptability of PSSUQ. Presented at the 9th Annual Americas Conference on Information Systems; Omaha, NE: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Genevro JL, Marshall T, Miller T, the Center for the Advancement of Health Report on bereavement and grief research. Death Studies. 2004;28:491–575. doi: 10.1080/07481180490461188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden AJ, Dalgleish T. Is prolonged grief distinct from bereavement-related posttraumatic stress? Psychiatry Research. 2010;178:336–341. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribble JN, Miller HG, Cooley PC, Catania JA, Pollack L, Turner CF. The impact of T-ACASI interviewing on reported drug use among men who have sex with men. Substance Use and Misuse. 2000;35:869–890. doi: 10.3109/10826080009148425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfeld RA. The Mood Disorder Questionnaire: A Simple Patient-Rated Screening Instrument for Bipolar Disorder. Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2002;4(1):9–11. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v04n0104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz MJ, Siegel B, Holen A, Bonanno GA, Milbrath C, Stinson CH. Diagnostic criteria for complicated grief disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154:904–10. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.7.904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyert DL, Kung HC, Smith BL. Deaths: preliminary data for 2003. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2005;53:1–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Truax P. Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:12–19. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaprio J, Koskenvuo M, Rita M. Mortality after bereavement: a prospective study of 95,647 widowed persons. American Journal of Public Health. 1987;77:283–287. doi: 10.2105/ajph.77.3.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kersting A, Dolemeyer , Steinig J, Walter F, Kroker K, Baust K, Wagner B. Brief Internet-based intervention reduces posttraumatic stress and prolonged grief in parents after the loss of a child during pregnancy: A randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 2013;82:372–381. doi: 10.1159/000348713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kersting A, Kroker K, Schlicht S, Baust K, Wagner B. Efficacy of cognitive behavioral internet-based therapy in parents after the loss of a child during pregnancy: pilot data from a randomized controlled trial. Archive of Women’s Mental Health. 2011;(14):465–477. doi: 10.1007/s00737-011-0240-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A. Culture, bereavement, and psychiatry. Lancet. 2012;379:608–609. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60258-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange A, Schrieken B, Van de Ven J, Bredeweg B, Emmelkamp PMG, van der Kolk J, Lydsdottir L, Massaro M, Reuvers A. “Interapy: The effects of a short protocolled treatment of posttraumatic stress and pathological grief through the internet. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2000;28:175–192. [Google Scholar]

- Lannen PK, Wolfe J, Prigerson HG, Onelov E, Kreicbergs UC. Unresolved grief in a national sample of bereaved parents: impaired mental and physical health 4 to 9 years later. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26:5870–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.6738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latham AE, Prigerson HG. Suicidality and bereavement: Complicated grief as psychiatric disorder presenting greatest risk for suicidality. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2004;34:350–362. doi: 10.1521/suli.34.4.350.53737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthal WG, Nilsson M, Kissane DW, Breitbart W, Kacel E, Jones EC, Prigerson HG. Underutilization of mental health services among bereaved caregivers with prolonged grief disorder. Psychiatric Services. 2011;62:1225–1229. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.62.10.1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litz BT. Treatment and dissemination of treatment programs: Summary and discussion. In: Neria Y, Gross R, Marshall R, editors. Treatment, research, and public mental health in the wake of a terrorist attack. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; Sep 11, 2001. pp. 446–456. [Google Scholar]

- Litz BT, Bryant RA. Early cognitive-behavioral interventions for adults. In: Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ, Cohen JA, editors. Effective treatments for PTSD: Practice guidelines from the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2009. pp. 117–135. [Google Scholar]

- Litz BT, Engel CC, Bryant R, Papa A. A randomized controlled proof of concept trial of an internet-based therapist-assisted self-management treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:1676–1683. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06122057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litz BT, Gray MJ, Bryant R, Adler AB. Early intervention for trauma: Current status and future directions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2002;9:112–134. [Google Scholar]

- Maercker A, Brewin CR, Bryant RA, Cloitre M, Reed GM, van Ommeren , Saxena S. Proposals for mental disorders specifically associated with stress in the International Classification of Diseases-11. Lancet. 2013 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62191-6. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maciejewski PK, Zhang B, Block SD, Prigerson HG. An empirical examination of the stage theory of grief. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;297:716–23. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.7.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melville KM, Casey LM, Kavanagh DJ. Dropout from Internet-based treatment for psychological disorders. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2010;49:455–471. doi: 10.1348/014466509X472138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris SB. Estimating effect sizes from pretest-posttest-control group designs. Organizational Research Methods. 2008;11:364–386. [Google Scholar]

- Mostofsky E, Maclure M, Sherwood JB, Tofler GH, Muller JE, Mittleman MA. Risk of acute myocardial infarction after the death of a significant person in one's life: The determinants of MI onset study. Circulation. 2012;125:491–496. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.061770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz RF, Mrazek PJ, Haggerty RJ. Institute of Medicine report on prevention of mental disorders: Summary and commentary. American Psychologist. 1996;51:1116–1122. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.51.11.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman MG, Szkodny LE, Llera SJ, Przeworski A. A review of technology-assisted self-help and minimal contact therapies for anxiety and depression: Is human contact necessary for therapeutic efficacy? Clinical Psychology Review. 2011;31(1):89–103. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papa A, Sewell MT, Garrison-Diehn C, Rummel C. A randomized open trial assessing the feasibility of behavioral activation for pathological grief responding. Behavior Therapy. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2013.04.009. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson HG, Bierhals AJ, Kasl SV, Reynolds CF, III, Shear MK, Newsom JT, Jacobs S. Complicated grief as a disorder distinct from bereavement-related depression and anxiety: A replication study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;153:1484–1486. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.11.1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson HG, Bierhals AJ, Kasl SV, Reynolds C, Shear MK, Day N, Jacobs S. Traumatic grief as a risk factor for mental and physical morbidity. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154:616–623. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.5.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson HG, Frank E, Kasl SV, Reynolds CFIII, Anderson B, Zubenko GS, Kupfer DJ. Complicated grief and bereavement-related depression as distinct disorders: Preliminary empirical validation in elderly bereaved spouses. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152:22–30. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson HG, Horowitz MJ, Jacobs SC, Parkes CM, Aslan M, Goodkin K, Maciejewski PK. Prolonged grief disorder: Psychometric validation of criteria proposed for DSM-V and ICD-11. PLoS Medicine. 2009;6:e1000121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochlen AB, Zack JS, Speyer C. Online Therapy: Review of relevant definitions, debates, and current empirical support. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2004;3(60):269–283. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schut H, Stroebe MS, van den Bout J, Terheggen M. The efficacy of bereavement interventions: Determining who benefits. In: Stroebe MS, Hansson RO, Stroebe W, Schut H, editors. Handbook of bereavement research: Consequences, coping, and care. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001. pp. 705–737. [Google Scholar]

- Shear K, Frank E, Houck PR, Reynolds CF. Treatment of complicated grief: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;293:2601–2608. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.21.2601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA. The Drug Abuse Screening Test. Addictive Behaviors. 1982;7:363–371. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(82)90005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spek V, Cuijpers P, Nyklícek I, Riper H, Keyzer J, Pop V. Internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy for symptoms of depression and anxiety: A meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine. 2007;37:319–328. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe W, Abakoumkin G, Stroebe M. Beyond depression: yearning for the loss of a loved one. Journal of Death and Dying. 2010;61:85–101. doi: 10.2190/OM.61.2.a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderwerker LC, Prigerson HG. Social support and technological connectedness as protective factors in bereavement. Journal of Loss and Trauma. 2004;9:45–57. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Houwen K, Schut H, van den Bout J, Stroebe M, Stroebe W. The efficacy of a brief Internet based self-help intervention for the bereaved. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2010;48:359–367. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner B, Knaevelsrud C, Maercker A. Internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy for complicated grief: A randomized controlled trial. Death Studies. 2006;30:429–453. doi: 10.1080/07481180600614385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner B, Maercker A. An Internet-based cognitive behavioral intervention for complicated grief: A pilot study. Giornale Italiano di Medicina del Lavoro ed Ergonomia. 2008;30(Suppl B):B47–B53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Huska JA, Keane TM. The PTSD Checklist–Civilian Version (PCL-C) Boston, MA: National Center for PTSD; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Weigold A, Weigold IK, Russell EJ. Examination of equivalence of self-report survey-based paper-and-pencil and Internet data collection methods. Psychological Methods. 2013;18(1):53–70. doi: 10.1037/a0031607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittouck C, Van Autreve S, De Jaegere E, Portzky G, van Heeringen K. The prevention and treatment of complicated grief: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2011;31:69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M, Mattia J. The Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire: Development, reliability, and validity. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2001;42(3):175–189. doi: 10.1053/comp.2001.23126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]