Abstract

Behavioral inhibition is a temperament assessed in the toddler period via children’s responses to novel contexts, objects, and unfamiliar adults. Social reticence is observed as onlooking, unoccupied behavior in the presence of unfamiliar peers and is linked to earlier behavioral inhibition. In the current study, we assessed behavioral inhibition in a sample of 262 children at ages two and three, and then assessed social reticence in these same children as they interacted with an unfamiliar, same age, and same sex peer, at 2, 3, 4, and 5 years of age. As expected, early behavioral inhibition was related to social reticence at each age. However, multiple trajectories of social reticence were observed including High-Stable, High-Decreasing, and Low-Increasing, with the High-Stable and High-Decreasing trajectories associated with greater behavioral inhibition compared to the Low-Increasing trajectory. In addition, children in the High-Stable social reticence trajectory were rated higher than all others on 60-month Internalizing problems. Children in the Low-Increasing trajectory were rated higher on 60-month Externalizing problems than children in the High-Decreasing trajectory. These results illustrate the multiple developmental pathways for behaviorally inhibited toddlers and suggest patterns across early childhood associated with heightened risk for psychopathology.

Keywords: Temperament, Behavioral Inhibition, Social Reticence, Behavior Problems, Peers

Behavioral inhibition, identified by wariness to uncertainty or novelty in toddlerhood, is thought of as one of most well-characterized temperaments (Fox, Henderson, Marshall, Nichols, & Ghera, 2005; Kagan & Moss, 1962). It is generally assessed in the late infant and toddler periods by observing children’s reactions to unfamiliar contexts, novel objects, and unfamiliar adults. As well, individual differences in levels of behavioral inhibition have been linked to a number of child and adolescent outcomes, such as social reticent behaviors in childhood or later social anxiety.

Examining relations between behavioral inhibition and social behavior, Coplan and colleagues (1994) found that behaviorally inhibited toddlers displayed what they termed social reticence in the presence of novel, or unfamiliar, peers. Specifically, these children were observed to display onlooking, unoccupied behavior, and they did not engage in either social or solitary play (Coplan, Rubin, Fox, Calkins, & Stewart, 1994). Rubin and colleagues (1997; 2002) also explored associations among behavioral inhibition, observed in various contexts at age two, and social reticence, observed with unfamiliar peers at ages two and four. While behavioral inhibition was modestly correlated with social reticence, less than a third of the sample was both highly inhibited and reticent concurrently at age two (Rubin et al., 1997). Furthermore, modest associations were found across the two-year span of time between the measures of behavioral inhibition or social reticence at age two and social reticence at age four (Rubin et al., 2002). In a parallel study, Fox and colleagues (2001) examined the associations between behavioral inhibition measured at one and two years of age and social reticence with unfamiliar peers at four years of age, grouping children based on the consistency with which they displayed behavioral inhibition and social reticence across the three assessments. Twenty-six percent of children showed consistently high behavioral inhibition and social reticence, while 38% showed high behavioral inhibition in toddlerhood and lower social reticence at the 4-year assessment (Fox et al., 2001). Thus, while early behavioral inhibition does display some continuity with social reticence behavior across early childhood, these links also evince discontinuity and changes across time for many children. Support for these different patterns also comes from Asendorpf’s (1990) theory of social inhibition as well as Gray’s (1987) motivational framework for individual differences in approach and avoidance. These theories posit physiological differences as reflected in reactivity of the behavioral inhibition system may underlie the associations between behavioral inhibition to novel objects and persons and social reticence to unfamiliar social partners. In contrast, children’s inhibition in more familiar contexts may reflect their individual level of general inhibition as well as their relationship with the familiar social partners or settings (Asendorpf, 1990). Furthermore, levels of inhibition to the unfamiliar may change across development due to changes in children’s regulatory skills and social-evaluative constructs.

An understanding of these changes in the expression of behavioral inhibition and its manifestation in peer contexts is important for multiple reasons. First, as development continues beyond toddlerhood, peers become increasingly salient to a child’s social world (Rubin, Burgess, & Hastings, 2002). Hence, the expression of temperament is modified and amplified by the social context. The display of a temperamental style within different social contexts and the effect of social contexts on the expression of the temperament are therefore of importance. For example, Fox et al. (2001) found that behaviorally inhibited children placed into non-maternal child care were less likely to express social reticence as preschoolers compared to equally inhibited children who remained under the exclusive care of a parent. In a parallel study, Almas et al. (2011) reported that negative reactive infants (an infant profile associated with toddler behavioral inhibition; Kagan & Snidman, 1991) experiencing positive peer interactions in day care at age 2 displayed less social reticence when observed in a social dyad with an unfamiliar peer at age 3, compared to those negative reactive infants who stayed at home. While informative, these existing studies of the links between behavioral inhibition and social reticence have relied on concurrent or two time-point longitudinal studies (e.g., Fox et al., 2001; Rubin et al., 1997; 2002). Therefore, exploring how early behavioral inhibition is related to longitudinal patterns of socially reticent behavior with unfamiliar peers repeatedly across development provides an important opportunity to elucidate the manifestation of temperament in trajectories of social behavior in novel settings across early childhood. While interactions with familiar peers may occur on a more regular basis throughout the lifespan, individual abilities in approaching unfamiliar others may be more directly related to underlying temperamental traits, as well as relate to poor adjustment across periods of transition (Asendorpf, 1990). The current study examines these longitudinal patterns of individuals within dyadic interactions (i.e., across multiple levels of analysis), providing a more robust view of individual differences in the development of social behavior, while clarifying the associations between early observed behavioral inhibition and various patterns of social behavior in a novel context across time.

Second, a good deal of work suggests that behavioral inhibition is a risk factor for the emergence of anxiety disorders in later childhood and adolescence (e.g., Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2009; Schwartz, Snidman, & Kagan, 1999). Measures of behavioral inhibition and social reticence typically correlate with greater internalizing behavior problems throughout childhood and adolescence (e.g., Fox et al., 2001; Muris, Merckelbach, Wessel, & van de Ven, 1999; Rubin et al., 2002; Volbrecht & Goldsmith, 2010) and studies have reported specific relations between behavioral inhibition and social anxiety (e.g., Gladstone et al., 2005; Muris, van Brakel, Arntz, & Schouten, 2011; Schwartz, Snidman, & Kagan, 1999). Furthermore, patterns of consistently high behavioral inhibition and/or social reticence from toddlerhood through middle childhood have been associated with greater risk for phobias (Hirshfeld et al., 1992; Hirshfeld-Becker, Biederman, Henin, Faraone, Davis et al., 2007) and social anxiety (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2009). Similarly, patterns of uninhibited behavior and solitary-active social behavior have been associated with greater externalizing symptoms and problems (Hirshfeld-Becker et al., 2002; 2006; Hirshfeld-Becker, Biederman, Henin, Faraone, Micco et al., 2007). Connecting these longitudinal patterns of behavioral inhibition and social reticence with unfamiliar peers to internalizing and externalizing behavior problems provides more clinically relevant distinctions between these trajectories across early childhood. In addition, this type of analysis clarifies whether these outcomes stem from levels of BI and social reticence in toddlerhood alone or the maintenance of and changes in these individual differences over time.

Summary and Hypotheses

The first aim of the current study was to investigate links between behavioral inhibition observed in the laboratory and social reticence observed in unfamiliar, same-sex, same-age dyads from 24 to 60 months of age in a sample selected for a wide range of infant temperamental reactivity to novelty. Multiple longitudinal trajectories of social reticence were expected, as opposed to a single trajectory, due to the moderate stability and continuity in behavioral inhibition and social reticence, reported across many studies and developmental periods (See Degnan & Fox, 2007, for a review). We expected multiple trajectories over the early childhood period for the current measures of observed social behavior with unfamiliar peers, similar to patterns reported in other studies (Booth-LaForce & Oxford, 2008; Letcher et al., 2009; Oh et al., 2008). In addition, greater toddler behavioral inhibition was expected to be positively associated with trajectories characterized by high levels of social reticence in toddlerhood regardless of whether the trajectories remained high, increased further, or decreased over the course of early childhood.

The second aim of the current study was to examine the predictive validity of the social reticence trajectories by examining associations with mother-reported behavior problems at 60 months of age. Overall, internalizing and externalizing behavior problem ratings were expected to further differentiate the social reticence trajectories. Children who followed a pattern of consistently high social reticence were expected to be perceived by mothers as higher on internalizing problems, relative to the other trajectories. In contrast, children who followed a pattern of consistently low social reticence were expected to be perceived by mothers as lower on internalizing problems, but higher on externalizing problems, relative to the other trajectories.

Method

Participants

As part of a longitudinal study conducted in a large metropolitan area of the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, families were contacted by mail and screened by phone to ensure that infants were born full-term, had not experienced any serious illnesses or problems in development thus far, and were not on any long-term medication. As a result, 779 infants who met these criteria were brought into the laboratory at 4 months of age for an additional temperament screening, during which affect (positive and negative) and motor reactivity during the presentation of novel visual and auditory stimuli were observed (for more details, see Hane, Fox, Henderson, & Marshall, 2008). Three-hundred and fifteen infants (151 males, 164 females) were selected to continue in the study based on their temperamental reactivity to novelty: high negative/high motor/low positive reactive (n = 105); high positive/high motor/low negative reactive (n = 103); low to average negative/positive/motor reactive (n = 83); and high negative/positive/motor reactive (n = 24). This provided a sample of infants widely distributed on both negative and positive reactivity to novelty dimensions, but with a wider-range of temperamental reactivity than would be seen in a random community sample. Of these infants, 63.8 % were Caucasian, 14 % were African American, 3.5 % were Hispanic, 2.2 % were Asian, 1.3 % were ‘other,’ and 15.2% were of mixed ethnicity. Information regarding family income was not collected, however, most mothers (76.8 %) and fathers (69.2 %) were at least college educated, with some mothers (22.5 %) and fathers (28.6 %) having at least a high school education, and the other mothers’ (0.6 %) and fathers’ (2.2 %) education was not reported. Across infancy (up to 24 months), 81.3 % families were married, 0.9 % were divorced or separated, 6.0 % were single mothers, 0.6 % families were married by common law, 1.0 % families reported some ‘other’ arrangement, and 10.2 % did not report their marital status.

Procedures

Following the temperament screening at 4 months of age, infants were assessed at 24, 36, 48, and 60 months of age. At 24 and 36 months, behavior and affect were observed in the laboratory during a standard behavioral inhibition paradigm (e.g., Fox et al., 2001; Kagan, Reznick, & Snidman, 1987). In addition, at 24, 36, 48, and 60 months, each child was observed in the laboratory interacting with an unfamiliar, same-age, same-sex peer, recruited from the community without consideration of their temperamental reactivity. After the 24-month peer assessment, pairs were shuffled at each subsequent assessment in order to maintain the unfamiliar nature of the dyad. At each age (24 through 60 months), the dyads were observed during identical freeplay, cleanup, and social problem-solving tasks. During the 60-month assessment, mothers were asked to report on child behavior problems.

Measures

Behavioral Inhibition

At both 24 and 36 months of age, a laboratory visit was conducted, during which mothers and their children participated in a paradigm designed to assess behavioral inhibition (e.g., Fox et al., 2001; Kagan et al., 1987). Stranger, Robot, and Tunnel tasks were used to characterize behavioral inhibition for this study (e.g., White, McDermott, Degnan, Henderson, & Fox, 2011, for details). Each task was independently and reliably coded (intra-class correlations, ICCs) for measures of latency to vocalize (24mo.: r = .78; 36mo.: r =.98), latency to approach/touch the stimuli (24mo.: r = .86; 36mo.: r = .93), and the proportion of time spent in proximity to mom (24mo.: r = .87; 36mo.: r = .98). Across episodes, measures of latency to vocalize (24mo.: M=41.95, SD=34.69; 36mo.: M=35.69, SD=34.34), latency to approach/touch the stimuli (24mo.: M=90.99, SD=28.30; 36mo.: M=85.80, SD=29.42), and proximity to mom (24mo.: M=0.31, SD=0.29; 36mo.: M=0.48, SD=0.27), were standardized and averaged to create an overall score for behavioral inhibition at each age (24mo.; M = .00, SD = .50, α = .87; 36mo.: M = .00, SD = .59, α = .98). Measures of behavioral inhibition were significantly correlated across the two age points, r = .33, p = .00, and were averaged together to form a composite measure of behavioral inhibition in toddlerhood, M = .00, SD = .47, n = 262.

Social Reticence

Children interacted with an unfamiliar peer in the laboratory during identical freeplay, cleanup, and social problem-solving episodes at 24, 36, 48, and 60 months of age. Children were introduced in the hallway and then led into the playroom to begin the assessment. Mothers remained in the room during the 24- and 36-month assessments, but were in an adjoining room for the 48- and 60-month assessments, as would be developmentally appropriate for children at these ages. When in the room, mothers were instructed to inhibit themselves from initiating any contact with the children. The interactions were videotaped through a one-way mirror for later behavioral coding. A team of coders was assigned to each episode at each age, with a lead coder training and supervising coding of each task and age point. Inter-rater reliability was achieved on 10% or more of each type of interaction prior to coding the remainder of the sample.

Freeplay episode

For the first task, a broad range of age-appropriate toys were scattered across the floor and children were allowed to play for 10 minutes. Behavior was rated in 2- minute epochs for wariness and unfocused/unoccupied behavior. Wariness was defined as a hesitancy to play with the toys and included behaviors such as hovering, watching, and selfsoothing. Unfocused/unoccupied was defined as time spent disengaged from any activity. Ratings ranged from 1 (none observed in epoch) to 7 (observed throughout epoch). Inter-rater reliability (ICCs) was computed on 16-36% of the sample at each age and ranged from .73 to .94 (M = .82). Ratings for wariness and unfocused/unoccupied behavior across epochs were averaged together at each age (M range: 1.55 – 2.82; SD = .38 – 1.06; α range: .67 - .88; mean α = .78) to index social wariness during Freeplay.

Clean-up episode

Following the Freeplay episode, children were instructed by the experimenter to clean up the toys and were left for a maximum of 5 minutes to clean up together. Coders assessed the duration of time (in seconds) spent cleaning up the toys, refusing to clean up the toys (including continuing to play), and unoccupied in either play or clean up behavior. Interrater reliability was computed on 10-20% of the sample at each age and (ICCs) ranged from .82 to .90 (M = .86). Similar to others in the literature (Coplan et al., 1994; Rubin et al., 2002), the proportion of time unoccupied/onlooking was created at each age by dividing the amount of time unoccupied by the total time given to clean up the toys (M range: .07 - .27; SD = .09 – .25).

Social problem-solving episode

Following the Clean-up episode, children were asked to share a developmentally appropriate toy typically designed for one child’s use: a stationary tricycle at 24 months, a stationary car at 36 months, a movable vehicle at 48 months, and a portable, learning system (i.e., Leapster®) at 60 months (See Walker, Henderson, Degnan, & Fox, 2013, for more details). At each age, the experimenter entered the room with the special toy, set it down in the middle of the room or table, told the children they only had one special toy so they must share and take turns, and then left the room for 5 minutes. Social initiations were coded based on schemes used by Rubin and Krasnor (1983) and Stewart and Rubin (1995).

An attempt to get the toy was coded when the child was not in possession of the toy and initiated an interaction in order to gain control and/or make it clear to the peer, that he or she wanted a turn. Each attempt to get the toy was further classified by the type of strategy used to achieve the goal: Passive (e.g., pointing or hovering), Active (e.g., touching, hitting, or taking), or Verbal (e.g., asking or telling). Agreement between coders (ICCs) was computed on 17-47% of the sample at each age and ranged from .84 to .97 (M=.92) for attempts to get the toy. ICCs for Passive social problem solving strategies, the focus of the current analyses, ranged from .72 to .92 (M=.80). A measure of the proportion of times using passive problem-solving strategies was calculated at each age by dividing the frequencies of passive strategies by the total number of attempts to get the toy (M range: .04 - .14; SD range: .17 - .30).

Social reticence composites

Social wariness from freeplay, proportion of time Unoccupied/onlooking from clean-up, and proportions of Passive strategies used in social problem-solving were standardized and averaged to represent social reticence at 24 (M = -.01, SD = .65, n = 226), 36 (M = .00, SD = .65, n = 225), 48 (M = .00, SD = .73, n = 215), and 60 months (M = .00, SD = .66, n = 210). This composite was formed to align with the current definition of social reticence as unoccupied and passive behavior with unfamiliar peers, as presented by Rubin and colleagues (2002), including multiple measures of unoccupied and passive behavior across freeplay, clean-up, and cooperative tasks. This composite at 60 months of age was also reported for this sample in a recent paper by Degnan and colleagues (2011). While each of these behaviors may assess social wariness and passivity in different contexts, their combination is thought to index a robust assessment of socially reticent behavior, whereby children displayed higher or lower reticence across tasks, rather than during a single task. The convergence of behaviors across tasks does seem to vary with age, with certain behaviors being more indicative at certain ages; see Table 1 for results across time for single factor principal component analysis (PCA) results. However, in order to examine developmental change, each composite included all three measures in order to remain consistent across assessment point and with previous literature using multi-task composites of social reticence behavior.

Table 1.

Principal component analysis loadings of social reticence measures across time.

| 24-months | 36-months | 48-months | 60-months | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eigenvalue | 1.32 | 1.42 | 1.49 | 1.32 |

|

| ||||

| FP social wariness | .81 | .83 | .68 | .77 |

| CL uninvolved/unoccupied | .81 | .83 | .78 | .59 |

| SPS passive strategies | .08 | -.19 | .65 | .62 |

Note: FP=freeplay, CL=cleanup, SPS=social problem-solving

60-month outcome measures

Child behavior checklist (CBCL 1.5-5; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000)

The CBCL was used to assess clinically relevant child internalizing and externalizing behavior problems at 60 months of age. Mothers used a 3-point scale to rate how often their children displayed a series of behavior problems, with 0 = never, 1 = sometimes, and 2 = often. The CBCL can be used to compute DSM-related subscales and the current study focused on those of Anxiety (7 items), AD/HD (6 items), and Oppositional Defiant (7 items). As Achenbach and Rescorla (2000) have suggested for developmental research, the raw scores were analyzed in the present study. Anxiety raw scores ranged from 0 to 12 (M = 2.38, SD = 2.19). AD/HD raw scores ranged from 0 to 12 (M=3.17, SD = 2.47). Oppositional Defiant raw scores ranged from 0 to 11 (M = 2.70, SD = 2.42).

MacArthur health and behavior questionnaire (HBQ; Armstrong, Goldstein, & MacArthur Working Group on Outcome Assessment, 2003)

The HBQ was used as a measure of children’s clinically relevant behavior problems at 60 months of age. Mothers used a 3-point scale to rate how often their children displayed a series of behavior problems, with 0 = never, 1 = sometimes, and 2 = often. For the current paper, the broad-band subscales of externalizing symptoms, AD/HD symptoms, and internalizing symptoms were used, as they overlapped most consistently with the DSM subscales from the CBCL. Externalizing symptoms consisted of an average across 31 items assessing the frequency of behaviors associated with oppositional defiance, conduct problems, overt hostility, and relational aggression (M = .22, SD = .19). AD/HD symptoms consisted of an average across 15 items assessing both inattention and impulsivity (M = .44, SD = .36). Internalizing symptoms consisted of an average across 29 items assessing depression, overanxious behavior, and separation anxiety (M = .19, SD = .18).

60-month internalizing and externalizing composites

In order to form more robust measures of clinically relevant symptoms of behavior problems, standardized measures from the CBCL and HBQ were entered into a two-component PCA to form two general components, externalizing and internalizing behavior problems. Measures of CBCL Oppositional Defiant, CBCL AD/HD, HBQ Externalizing, and HBQ AD/HD loaded highly on the externalizing component (n = 213; Eigenvalue = 3.11; average loading = .83) and did not load highly on the other component (average loading = .29). Measures of CBCL Anxiety and HBQ Internalizing loaded highly on the internalizing component (n = 213; Eigenvalue = 1.28; average loading = .90) and did not load highly on the other component (average loading = .32). Then, separate PCAs were run to create an externalizing component score (M = -.02, SD = .98) including the four measures of externalizing behavior problems, and an internalizing component score (M = .03, SD = 1.01) including the two measures of internalizing behavior problems. While these measures represent clinically relevant symptom levels, they do not include actual clinical diagnoses, and therefore, are referred to as internalizing and externalizing behavior problems.

Summary of Measures

Of the 315 participants recruited at 4 months, 226 had complete data at 24 months, 225 had complete data at 36 months, 221 had complete data at 48 months, and 199 had complete data at 60 months. Reasons for missing data included technical difficulties with the video collection, difficulty scheduling laboratory visits, families relocating, and 13 families who declined participation between recruitment and 60 months of age (i.e., permanent attrition). Given the interest in whether behavioral inhibition predicted social reticence over time, only those who had behavioral inhibition data were used for analyses (n=262). Those missing behavioral inhibition data were not significantly different from those not missing behavioral inhibition data by gender, χ2 (1, 315) = 0.02, p = .90, ethnicity (minority status = 0), χ2 (1, 315) = 1.43, p = .23, 4-month temperament group, χ2 (3, 315) = 7.22, p = .07, maternal education (less than a college education=0), χ2 (1, 313) = 0.51, p = .48, or any of the measures of social reticence or behavior problems (all ps > .05). Furthermore, the longitudinal data analysis procedure used maximum likelihood estimation (MLE), which allows for missing data longitudinally and assumes the data are missing at random (Little & Rubin, 1987; Muthén & Muthén, 2010). Data used for analysis included the behavioral inhibition, social reticence, and internalizing and externalizing measures. An examination of these variables suggested that patterns of missing data did not violate the assumption that they were missing completely at random (MCAR), Little’s MCAR χ2 (122) = 122.34, p = .47.

Data Analysis Plan

Growth mixture modeling, a specific type of structural equation modeling (SEM), was used to examine the longitudinal trajectories of social reticence across early childhood. In order to estimate multiple growth trajectories, latent class growth analysis (LCGA; Jones, Nagin, & Roeder, 1998; Muthén, 2004) was performed using Mplus 6.11 (Muthén & Muthén, 2010). Part of this analysis technique involves latent growth analysis (LGA; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002), also called hierarchical linear modeling (HLM), which estimates individual trajectories across repeated measures, thus providing an average starting point (i.e., intercept), an average level of growth (i.e., slope), and variance around those estimates. Another part of LCGA is latent class analysis (LCA; Muthén, 2001) that identifies unmeasured (i.e., latent) class membership among observed or estimated indicators. The current study used a growth mixture model, whereby LGA and LCA are combined into one analysis of multiple growth trajectories (i.e., LCGA). This type of mixture model capitalizes on the fact that these analyses offer two main advantages over traditional cluster techniques. First, use of SEM’s maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) method assumes the data are missing at random, which allows the model parameters to be informed by all cases that contribute a portion of the data, and is recommended as an appropriate way to accommodate missing data (Little & Rubin, 1987; Schafer & Graham, 2002). Second, unlike traditional cluster analysis algorithms, which group cases near each other by some definition of distance (e.g., Euclidean distance for k-means cluster analysis), the LCA approach relies on a formal statistical model based on probabilities to classify cases. Case classification is based on Bayes’ theorem and computes a posterior probability (based on a function of the model’s parameters) of membership for each individual for each latent class (Dayton, 1998, McCutcheon, 1987, Muthén, 2004). These probabilities of membership then can be estimated in association with predictor or outcome measures of interest.

In the present study, longitudinal latent growth trajectories were estimated using the observed measures of social reticence at 24, 36, 48, and 60 months of age (See Figure 1). Then, behavioral inhibition was estimated as a predictor of the probability of membership in the latent growth trajectories. Finally, 60-month internalizing and externalizing scores were estimated within each of the growth trajectories and most probable trajectory membership was analyzed in a secondary series of Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to determine outcome differences by trajectory.

Figure 1.

Statistical model used to examine social reticence across early childhood (LCGA), behavioral inhibition (BI) as a predictor of class membership, and internalizing and externalizing problems as outcomes of class membership.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

A preliminary examination of differences on demographic measures (gender, ethnicity, and maternal education) and selected temperament group was conducted. T-tests of gender or ethnicity (minority vs. Caucasian) revealed no significant differences on behavioral inhibition, social reticence at any time point, or internalizing behavior problems (all ps > .05). However, there were significant gender and ethnicity differences on externalizing behavior problems, t (211) = 3.68, p < .001 and t (211) = 1.94, p = .05, respectively, indicating that males and those of a minority ethnic group were reported to have greater externalizing problems than females or those reported as Caucasian. A series of ANOVAs revealed no maternal education differences on behavioral inhibition, social reticence at 24, 36, and 48 months, or behavior problems (all ps > .05). Maternal education was significantly related to social reticence at 60 months, t (207) = - 2.67, p = .01, such that mother’s with at least a college education had children that displayed more social reticence at 60 months. Finally, ANOVAs revealed no 4-month selected temperament group differences on behavioral inhibition, social reticence, or behavior problems (all ps > .05). Due to these findings, maternal education was tested as a predictor of the social reticence trajectories and gender and ethnicity were included in the ANCOVAs predicting trajectory group differences on externalizing behavior problems. No other covariates were included in further analyses.

In addition, correlations between composite measures were examined (See Table 2). Toddler behavioral inhibition was significantly, positively associated with every measure of social reticence across early childhood. In addition, 36-month social reticence was positively associated with 60-month internalizing behavior problems and 24-month social reticence was negatively associated with 60-month externalizing behavior problems.

Table 2.

Inter-correlations between composite measures.

| 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. 24/36-mo. Behavioral Inhibition | .25** (226) | .16* (225) | .14* (215) | .16* (210) | .05 (213) | -.07 (213) |

| 2. 24-mo. Social Reticence | -- | .12 (196) | .16* (187) | -.03 (182) | .11 (186) | -.15* (186) |

| 3. 36-mo. Social Reticence | -- | .13 (207) | .13 (192) | .19* (191) | -.14 (191) | |

| 4. 48-mo. Social Reticence | -- | .21** (190) | .13 (184) | -.07 (184) | ||

| 5. 60-mo. Social Reticence | -- | .11 (190) | -.13 (190) | |||

| 6. 60-mo. Internalizing problems | -- | .04 (213) | ||||

| 7. 60-mo. Externalizing problems | -- |

Note: sample size for each correlation is in parentheses;

p < .05,

p < .01

Estimating Longitudinal Trajectories of Social Reticence

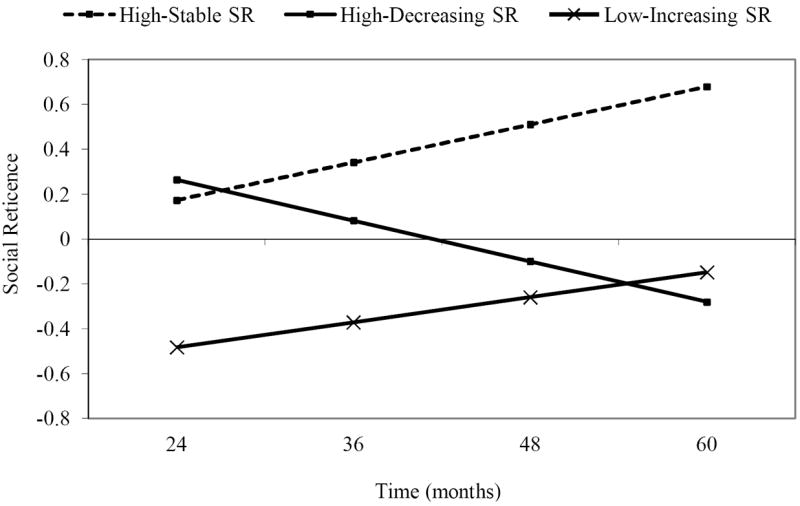

In the first step, LCGA models with 1 through 4 classes were tested to determine the optimal number of trajectories to describe social reticence across early childhood for the current sample. In order to achieve a stable model with reliable indices, the intercept and slope variance were allowed to vary across class, but was held to zero within class. In addition, the residual variances in the measures of social reticence were estimated and allowed to vary across classes. Model fit using the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC; D’Unger, Land, McCall, & Nagin, 1998) was 1800.51 for one class, 1544.36 for two classes, 1499.64 for three classes, and 1510.75 for four classes. In addition, the Lo-Mendell-Rubin Likelihood Ratio Test (LMR-LRT; Lo, Mendell, & Rubin, 2001) and the bootstrapped LRT (Nylund, Asparouhov, & Muthén, 2007) both showed that the 2-class model was significantly better than the 1-class model (ps < .001), and that the 3-class model was significantly better than the 2-class model (ps < .05), while the 4-class model was not significantly better than the 3-class model according to the LMR-LRT (p = .46) and the bootstrapped LRT reported reliability problems for 4 classes. In addition, the 4-class model produced problems with reliability of the overall Log-Likelihood. Given that a lower BIC value was combined with a significant LMR-LRT and bootstrapped LRT for the 3-class model and the convergence and reliability problems noted for the 4-class model, the 3-class model was chosen as the best-fitting model. The estimated mean level of social reticence at each age for each trajectory is plotted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Longitudinal Trajectories of Social Reticence (SR): Estimated Means from Latent Class Growth Analysis

The High-Stable social reticence trajectory represented 16% of the sample (n=43), had a high level of social reticence at age 2, with consistently higher levels and a non-significant increase across time, B = 0.17, z = 1.78, p = .07. The High-Decreasing social reticence trajectory represented 43% of the sample (n=112), had a high level of social reticence at age 2, and a significant decrease across time, B = -0.18, z = -5.13, p < .001. The Low-Increasing social reticence trajectory represented 41% of the sample (n=107), had a lower level of social reticence at age 2, and showed a significant increase in, but consistently lower levels of, social reticence across time, B = 0.11, z = 5.43, p < .001.

Toddler Behavioral Inhibition as a Predictor of Social Reticence Trajectories

As a second step, covariates were added to the model. First, given the preliminary findings with 60-month social reticence, maternal education was added to the model. However, it did not yield any significant differences between classes (all ps > .40) and in fact, increased the overall BIC (i.e., decreased model fit). In addition, none of the other demographic measures were significantly related to the social reticence trajectories (all ps > .05). Therefore, maternal education was removed from the model and none of the other demographic measures were included in all remaining analyses. Second, behavioral inhibition was added to the model to examine relations with class membership and significantly impacted the model loglikelihood, χ2 (2) = 64.20, p < .001, lowered the BIC to 1488.47, and showed significant relations to trajectory membership. Specifically, the High-Stable social reticence and the High-Decreasing social reticence trajectories displayed significantly greater behavioral inhibition, than the Low-Increasing social reticence trajectory, B=2.19, z=3.63, p<.001, Odds=8.94 and B=1.47, z=2.84, p<.01, Odds=4.35, respectively. Behavioral inhibition did not significantly differentiate the High-Stable social reticence trajectory, B=0.72, z=1.47, p=.14, Odds=2.05, from the High-Decreasing social reticence trajectory. Therefore, as toddler behavioral inhibition increases, the odds of following the High-Stable or the High-Decreasing social reticence trajectories remained higher, but the odds of following the Low-Increasing social reticence trajectory were significantly lower1. Figure 3 illustrates the association between toddler behavioral inhibition and the probabilities of membership in each social reticence trajectory.

Figure 3.

Influence of Behavioral Inhibition on the probabilities of Social Reticence (SR) trajectory membership.

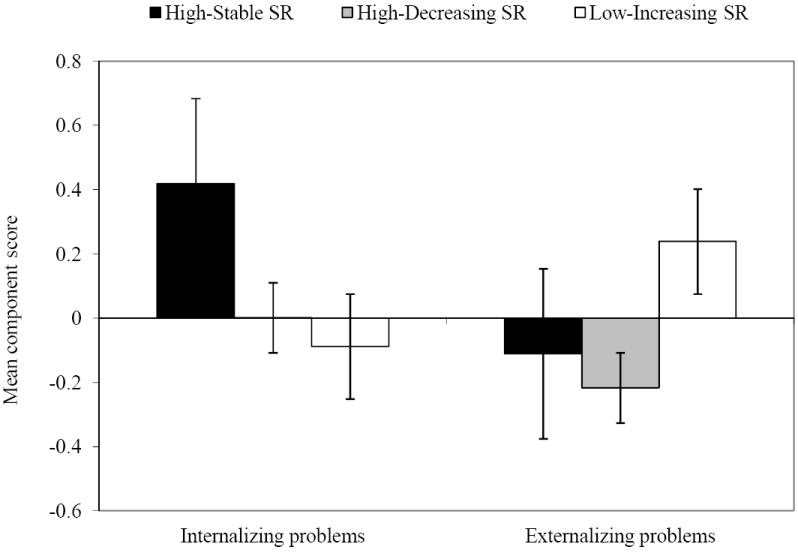

Behavior Problem Outcomes of Social Reticence Trajectories

In a final step, 60-month internalizing and externalizing scores were added to the model to examine trajectory differences in outcomes. To compare the estimated means within each trajectory statistically, the posterior probabilities of membership in each social reticence trajectory and the most probable trajectory for each individual were saved and examined in an ANOVA for internalizing problems and ANCOVA for externalizing problems. The model predicting externalizing problems controlled for gender and ethnicity as covariates. Results showed that the trajectory groups were significantly different on both internalizing and externalizing behavior problems, F(2, 212) = 3.26, p < .04 and F(2, 212) = 5.43, p < .01, respectively. Post-hoc comparisons revealed that the High-Stable social reticence trajectory had a greater level of 60-month internalizing problems than both the High-Decreasing and Low Increasing social reticence trajectories, ps < .05, while the Low-Increasing social reticence trajectory had a greater level of 60-month externalizing problems than the High-Decreasing social reticence trajectory, p < .01, and a trend effect for a greater level than the High-Stable social reticence trajectory, p = .06, (Figure 4). Therefore, children were rated by their mothers as greater on internalizing problems if they had a greater likelihood of following consistently high levels of social reticence from toddlerhood to early childhood, as opposed to following decreasing or lower levels over time. Children were rated by the mothers as greater on externalizing problems if they had a greater likelihood of following lower levels of social reticence from toddlerhood to early childhood, compared to following a decreasing pattern over time.

Figure 4.

Social reticence (SR) trajectory group differences on 60-month internalizing and externalizing behavior problems.

Discussion

The current study investigated a sample selected for infant temperamental reactivity to novelty in order to: 1) define multiple longitudinal trajectories of observed social reticence with unfamiliar peers from toddlerhood through early childhood, 2) determine whether the trajectories of social reticence were differentially associated with toddler behavioral inhibition, and 3) examine associations between the trajectories of social reticence and maternal report of behavior problems at 60 months of age. Using latent class growth analysis (LCGA; Muthén 2004), three longitudinal trajectories of social reticence across early childhood were revealed, with differential relations to both early behavioral inhibition in toddlerhood and later behavior problems at 60 months of age. These results demonstrate the role of early temperament in longitudinal patterns of observed social behavior with unfamiliar peers across early childhood, as well as the multiple developmental pathways behaviorally inhibited toddlers may follow. Potential internal and external processes for these differential developmental pathways are discussed as important for future investigations.

Previous longitudinal work investigating the stability of behavioral inhibition, or toddler wariness to social and non-social novelty, suggests that there is just as much discontinuity as continuity across early childhood in these constructs (see Degnan & Fox, 2007, for a review). While for some children the display of their reactivity to novelty is consistent across development, others may learn to cope, displaying less and less reactivity externally. In addition, toddlers with behavioral inhibition may be at risk for social withdrawal and social isolation as development continues, but not all inhibited toddlers develop these social behavior profiles (Fox et al., 2001; Rubin et al., 2009). Social reticence, a subtype of social withdrawal, has often been equated with behavioral inhibition and represents a style of social behavior where children observe peers from a distance, remaining unoccupied in either social company or non-social play (Coplan et al., 1994; Rubin et al., 2002). Previous discussions regarding behavioral inhibition and social inhibition suggest an underlying physiological profile reflective of an enhanced behavioral inhibition system responding to novel and unfamiliar contexts (Asendorpf, 1990; Gray, 1987). However, despite their overlapping features, previous empirical findings report moderate associations between behavioral inhibition and social reticence (e.g., Rubin et al., 1997; Rubin et al., 2002), suggesting that only a subset of behaviorally inhibited toddlers go on to display social reticence in childhood. Furthermore, previous longitudinal examinations of social behavior (e.g., social withdrawal, anxious solitude) across repeated assessments have focused on report measures, as opposed to observational assessments. The current study builds on this work by describing the longitudinal patterns of observed social behavior displayed in a certain context (e.g., with unfamiliar peers) across early childhood, as well as the links to early behavioral inhibition and later behavior problems. The present analysis and results greatly enhance developmental theory and knowledge regarding the links between early temperament, later social behavior, and their influence on risk for internalizing and externalizing behavior problems.

Informed by previous studies, multiple trajectories were expected to emerge for the current sample. Indeed, the current analysis found three longitudinal patterns of social reticence. A High-Stable social reticence trajectory represented about 15% of the sample and displayed high levels of social reticence at 24 months that remained high through 60 months of age. While there is limited evidence from previous longitudinal studies of a high, stable trajectory, one study found a trajectory with varying high levels of reported internalizing problems from toddlerhood to adolescence (Letcher et al., 2009). Moreover, the current study results reflect the repeated assessment with a novel peer, as opposed to repeated reports of behavior with familiar peers over time. In addition, while the High-Stable social reticence trajectory maintained high levels across time, it did evidence slightly lower levels of reticence at 24 months than the High-Decreasing trajectory, showing some consistency with moderate or moderate-increasing trajectories found in other studies (Letcher et al., 2009; Oh et al., 2008). Next, a High-Decreasing social reticence trajectory represented about 40% of the sample, suggesting that many toddlers who start with greater social reticence learn to cope with their reactivity and competently negotiate the novel peer environment over time. This is consistent with much of the previous work examining multiple trajectories using questionnaire or report methods, which has consistently found a moderate or high-decreasing pattern of social withdrawal across childhood (e.g., Booth-LaForce & Oxford, 2008; Letcher et al., 2009; Oh et al., 2008). Similarly, work exploring average growth trajectories across samples has often found declines in internalizing behavior or shyness across early childhood (e.g., Carter et al., 2010; Dennissen et al., 2008; Grady et al., 2012). Indeed, literature showing moderate links between early wariness to novelty and social reticence posits that some children may decline in their outward display of inhibition to novel social environments (Degnan & Fox, 2007; Rubin et al., 2009). It is important that future research further define this pattern of development by the within-child and environmental processes that may contribute to such changes in behavior across early childhood. Finally, a Low-Increasing social reticence trajectory was found to represent about 45% of the sample, displayed the lowest social reticence in toddlerhood that increased throughout early childhood, but remained lower than the High-Stable trajectory and as low as the High-Decreasing trajectory by the end of early childhood. Given that high social reticence is thought to represent a relatively extreme level in children’s social behavior, the existence of a low trajectory may represent a more normative trajectory. Indeed, a low pattern typically emerged in previous work examining multiple trajectories. While the current sample was selected, it included infants both high and low in negative reactivity to novelty; thus, a subset of children (i.e., low negative reactive) would be expected to evidence much lower levels of apprehension to novel social contexts, similar to the Low-Increasing trajectory from the current results. In sum, the current study found High-Stable, High-Decreasing, and Low-Increasing trajectories of social reticence across early childhood. These patterns were expected and are consistent with the current theory on socially inhibited behavior across contexts.

The second aim of the current study was to examine a traditional measure of toddler behavioral inhibition as a predictor of membership in the social reticence trajectories. Given the literature on the moderate links between behavioral inhibition and social reticence and the evidence for discontinuity in the sequelae of behavioral inhibition over time, it was expected that behavioral inhibition would differentiate the trajectories with initially higher social reticence from those with initially lower social reticence (Coplan et al., 1994; Rubin et al., 1997; 2002). Indeed, relations between singular measures of behavioral inhibition and social reticence were modest when each time point was considered independently (see Table 2). However, behavioral inhibition was associated with the probability of membership in the longitudinal trajectories of social reticence. Specifically, the High-Stable and High-Decreasing social reticence trajectories were associated with greater toddler behavioral inhibition, compared to the Low-Increasing trajectory. As behavioral inhibition did not differentiate the High-Stable and High-Decreasing trajectories, these results support the notion that behavioral inhibition is a temperament linked to social reticence that may evince multiple longitudinal patterns over time (Degnan & Fox, 2007; Fox et al., 2005). Overall, while some behaviorally inhibited toddlers may maintain their display of heightened social reticence when faced with novel social situations, there are also many who do not follow this trajectory of passive/wary behavior across early childhood.

The third aim of the current study was to examine the predictive validity of these patterns of social reticence with unfamiliar peers. Thus, parent-reported measures of internalizing and externalizing behavior problems were investigated as outcomes related to trajectory membership. As expected from previous work (e.g., Muris et al., 1999; Rubin et al., 2002; Volbrecht & Goldsmith, 2010), the High-Stable social reticence trajectory was associated with greater internalizing problems. Given few direct effects (see Table 2), it is noteworthy that the longitudinal pattern associated with higher behavioral inhibition and social reticence over time (i.e., the High-Stable trajectory) is what was associated with greater internalizing problems at age 60 months. This pattern may continue to be associated with the emergence of internalizing psychopathology in late childhood/early adolescence (e.g., Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2009; Hirshfeld et al., 1992). In comparison, the Low-Increasing social reticence trajectory was associated with greater externalizing problems at 60 months, compared to the High-Decreasing trajectory. It is possible that increases in parent reports of externalizing amongst this group may be a function of enhanced peer rejection and isolation over time due to their uninhibited nature. Further work examining the processes by which increasing social reticence and externalizing problems co-occur over early childhood is necessary to unpack these potential bi-directional influences. Finally, the High-Decreasing social reticence trajectory was associated with lower levels of all behavior problems, suggesting a possible resilience process (Degnan & Fox, 2007). Indeed, this confirms that children with heightened behavioral inhibition and social reticence in toddlerhood may display a decline in social reticence over time, protecting them from later behavior problems. It also suggests that normative increases in self-regulation may provide the mechanism by which some socially reticent children cope with their temperamental bias towards heightened reactivity.

Overall, the current study provides evidence for multiple developmental patterns in the display of social reticence across early childhood. Their association with a standard toddler behavioral inhibition assessment supports theory asserting a developmental link from behavioral inhibition to social reticence (Rubin et al., 2009), as well as that suggesting underlying physiological differences supportive of both behavioral profiles (Asendorpf, 1990). Furthermore, results showed differential outcomes associated with these trajectories. While previous work using survey data has suggested similar patterns of development for social reticence-related constructs, such as shyness and anxious solitude, across early and middle childhood, little to no work until now has examined longitudinal patterns of observed behavior, particularly with unfamiliar peers. Therefore, it was important to assess whether links between behavioral inhibition and social behavior with unfamiliar peers (i.e., observed social reticence) would map onto theoretical musings regarding the development of social withdrawal over time.

Any differences between the current patterns of data and the previous literature examining longitudinal trajectories may rest in the role of assessment context, such as school and home settings (Arbeau, Coplan, & Weeks, 2010; Early et al., 2002; Gazelle, 2006) compared to confronting an unfamiliar peer in a laboratory setting. In the current sample, some behaviorally inhibited toddlers continued on a stable path of reactivity to novelty and social reticence, and some declined in their display of inhibited behavior and socially withdrawn tendencies. Examining the differential links between these trajectories and internalizing and externalizing behavior problems provides greater clinical utility for these patterns of social behavior (De Los Reyes et al., 2013). However, future research is necessary to determine whether children who decline in their display of behavioral inhibition and social reticence also decline in their physiological reactivity to such contexts or merely learn how to mask the external display of their reactivity. Some studies suggest that behaviorally inhibited children may require a unique pattern of regulatory skills and attention processes in order to adaptively approach the social world (e.g., Karevold et al., 2011; Pérez -Edgar et al., 2010; White et al., 2011). In addition, parent psychopathology, parental behavior, and aspects of the parent-child relationship may impact the development of behavioral inhibition and social withdrawal over time (Coplan, Arbeau, & Armer, 2008; Crockenberg & Leerkes, 2006; Degnan et al., 2008; Hane, Cheah, Rubin, & Fox, 2008; Kennedy, Rapee, & Edwards, 2009; Lewis-Morrarty et al., 2012; Wood, McLeod, Sigman, Hwang, & Chu, 2003). With the current sample displaying these varying patterns of change over time, future analyses should examine which of these internal or external mechanisms impact later outcomes across trajectories.

An additional distinction between the present study and that of previous investigations was the focus on unfamiliar peer interactions. As described by Asendorpf (1990) and others, there are numerous distinctions to be made between social contexts involving familiar or unfamiliar peers or adults. In addition, the impact on these interactions may change over time, as interactions with familiar others only increase in their familiarity with every additional interaction. The implications for inhibition or reticence towards these different contexts also vary. While children may spend increasing amounts of time around familiar peers as they age, one’s ability to enter into a novel social interaction continues to be adaptive across development. In fact, one’s ability to negotiate new, unfamiliar social settings may be particularly helpful during school transition periods or when entering the workforce. Additional work is needed to compare and contrast children’s reticence to familiar and unfamiliar settings across development, linking individual patterns to outcomes across a variety of domains (e.g., academic, social, vocational, psychological). Furthermore, supplementary analyses regarding the types of behavioral inhibition (i.e., social or non-social) in relation to social reticence to unfamiliar peers suggests the importance of non-social inhibition to these types of social outcomes (i.e., with unfamiliar peers). While this may be surprising at first glance, this result supports theory suggesting that an overall general state of inhibition may predict reactivity to novelty across all unfamiliar contexts and stimuli (Asendorpf, 1990). Perhaps social inhibition measures would more directly predict outcomes in familiar social settings or reflect stability in familiar social inhibition across time. Additional research focused on different types of behavioral inhibition in relation to different social contexts (e.g., unfamiliar, familiar-peer, familiar-family) would help tease apart these potential links across development.

Strengths and Limitations

Previous work examining observed behavioral inhibition or social reticence over time has been limited by the changing nature of behavioral assessments across development. The strengths of the present study include the ability to model trajectories of observed behavior over time (i.e., intercept and slope, rather than just mean levels), as the same assessments and coding schemes were used to describe social reticence at each age point across early childhood. In addition, this study expanded knowledge about the development of social behavior to interactions with unfamiliar peers. Thus, the current study provides a detailed and specific analysis of early temperament, social reticence with unfamiliar peers, and behavior problems across early childhood. Furthermore, the use of multiple measurement techniques (i.e., observational and parent-report) limited the shared method variance in the current results. Indeed, there is minimal overlap between the aspects of behavior targeted in the peer dyad assessments and the items responded to on the parent-report measures, providing greater confidence in the predictive utility of the trajectories estimated in the current analysis.

The present study also has limitations that should be noted. While unoccupied/onlooking and passive behavior across contexts was used at each age to form a more robust measure of social reticence, these measures did not converge together equally at each assessment point. In addition, while the trajectories were found to be differentially associated with internalizing or externalizing behavior problems and the range of scores extends into the clinical range, the mean levels of these behavior problem scores were all within a normative range, suggesting that the frequency of diagnosable psychopathology at 60 months of age was relatively low, despite there being some scores that reached clinical levels. It is also noteworthy that the current study does not speak directly to the broader concepts of shyness and social withdrawal, or anxious solitude with familiar peers. Future work should continue to untangle what specific aspects of behavioral inhibition (e.g., Asendorpf, 1990) are linked to these other domains of development.

In addition, while LCGA is a useful analysis for longitudinal data, the present trajectories do not necessarily represent qualitatively distinct groups in the general population. Instead, they represent patterns within the sample examined (Bauer & Curran, 2004), which was over-selected for high and low negative reactivity to novelty and repeatedly assessed for social reticence with an unfamiliar peer across early childhood. The infant temperament groups were not associated with the measures of interest or the trajectories, but the current patterns of social reticence for this at-risk, community sample will only become established with replication and confirmation in other, similar samples. In addition, whereas the social partner remained novel across time, the repeated nature of the assessment tools may have decreased the novelty of the experimental context over time. Moreover, additional work is needed to explore the differential predictors and outcomes associated with these trajectories above and beyond toddler behavioral inhibition or 60-month behavior problems. Now that multiple trajectories are confirmed to exist in the current sample, work examining the role of potential intervening internal and external factors is needed to elucidate the role these trajectories play in the development of psychopathology and positive adaptation across childhood and into adolescence.

Summary

Analyses conducted on repeated measures of observed social reticence with unfamiliar peers across early childhood yielded three longitudinal patterns: High-Stable, High-Decreasing, and Low-Increasing. These trajectories were further defined by observed behavioral inhibition in toddlerhood and parent-report of internalizing and externalizing behavior problems at 60 months of age. In particular, the High-Stable social reticence trajectory was associated with higher behavioral inhibition, compared with the Low-Increasing social reticence trajectory, and was associated with higher Internalizing behavior problems, compared with the High-Decreasing and Low-Increasing social reticence trajectories. The High-Decreasing social reticence trajectory was associated with higher behavioral inhibition, compared with the Low-Increasing social reticence trajectory, but was associated with lower Internalizing behavior problems, compared with the High-Stable social reticence trajectory, and lower Externalizing behavior problems, compared with the Low-Increasing social reticence trajectory. In turn, the Low-Increasing social reticence trajectory was associated with lower behavioral inhibition, compared with the other two trajectories, was associated with lower Internalizing behavior problems, compared with the High-Stable social reticence trajectory, and was associated with higher Externalizing behavior problems, compared with the High-Decreasing social reticence trajectory. Overall, these results support theory suggesting that an inhibited temperament may result in both adaptive and maladaptive outcomes across development (Degnan, Almas, & Fox, 2010; Degnan & Fox, 2007). Future work is needed to clarify what intervening factors or processes support these differential patterns over time.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

A very special thank you goes to all of the families who participated in this study. This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (MH 074454, MH93349, and HD 17899) to Nathan A. Fox. We would like to thank the entire Child Development Lab and students, both at the University of Maryland and the University of Miami, who helped with data collection and behavioral coding for this project.

Footnotes

The model was also estimated using separate social (i.e., stranger) and non-social (i.e., robot and tunnel) composites of behavioral inhibition as predictors of membership in the social reticence trajectory classes (see Supplementary Material, for more details). The results showed that the non-social behavioral inhibition composite differentiated the High-Stable social reticence trajectory from the Low-Increasing social reticence trajectory, (B=1.42, z=2.50, p=.01), while the social behavioral inhibition composite did not significantly differentiate the trajectories (ps>.11). This result is interpreted as suggesting that stability in social reticence across early childhood is not merely reflective of an initially high level of inhibition to social stimuli alone. Given these results and the relatively high correlation between the social and non-social behavioral inhibition composites, r(262)=.49, p=.00, the overall composite across both social and non-social contexts was used in the main analyses to reflect children’s overall inhibition across multiple contexts.

References

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA preschool forms & profiles. Burlington, VT: Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Arbeau KA, Coplan RJ, Weeks M. Shyness, teacher-child relationships, and socio-emotional adjustment in grade 1. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2010;34:259–269. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong JM, Goldstein LH The MacArthur Working Group on Outcome Assessment. MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Psychopathology and Development. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press; 2003. Manual for the MacArthur Health and Behavior Questionnaire (HBQ 1.0) [Google Scholar]

- Asendorpf JB. Development of inhibition during childhood: evidence for situational specificity and a two-factor model. Developmental Psychology. 1990;26:721–730. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer DJ, Curran PJ. The integration of continuous and discrete latent variable models: Potential problems and promising opportunities. Psychological Methods. 2004;9:3–29. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.9.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth-LaForce C, Oxford ML. Trajectories of social withdrawal from grades 1 to 6: Prediction from early parenting, attachment, and temperament. Developmental Psychology. 2008;4:1298–1313. doi: 10.1037/a0012954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter AS, Godoy L, Wagmiller RL, Veliz P, Marakovitz S, Briggs-Gowan MJ. Internalizing trajectories in young boys and girls: The whole is not a simple sum of its parts. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2010;38:19–31. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9342-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronis-Tuscano A, Degnan KA, Pine DS, Pérez -Edgar K, Henderson HA, Diaz Y, et al. Stable early maternal report of behavioral inhibition predicts lifetime social anxiety disorder in adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48:928–935. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181ae09df. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coplan RJ, Arbeau KA, Armer M. Don’t fret, be supportive! Maternal characteristics linking child shyness to psychosocial and school adjustment in kindergarten. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:359–371. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9183-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coplan RJ, Rubin KH, Fox NA, Calkins SD, Stewart SL. Being alone, playing alone, and acting alone: Distinguishing among reticence and passive and active solitude in young children. Child Development. 1994;65:129–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockenberg SC, Leerkes EM. Infant and maternal behavior moderate reactivity to novelty to predict anxious behavior at 2.5 years. Development and Psychopathology. 2006;18:17–34. doi: 10.1017/S0954579406060020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayton CM. Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences, Series No 126. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. Latent class scaling analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Degnan KA, Almas AN, Fox NA. Temperament and the environment in the etiology of anxiety. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010;51:497–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02228.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degnan KA, Fox NA. Behavioral inhibition and anxiety disorders: multiple levels of a resilience process. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19:729–746. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407000363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degnan KA, Hane AA, Henderson HA, Moas OL, Reeb-Sutherland BC, Fox NA. Longitudinal stability of temperamental exuberance and social-emotional outcomes in early childhood. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47:765–780. doi: 10.1037/a0021316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degnan KA, Henderson HA, Fox NA, Rubin KH. Predicting social wariness in middle childhood: The moderating roles of child care history, maternal personality, and maternal behavior. Social Development. 2008;17:471–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00437.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Bunnell BE, Beidel DC. Informant discrepancies in adult social anxiety disorder assessments: links with contextual variations in observed behavior. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013;122:376–386. doi: 10.1037/a0031150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennissen JJA, Asendorpf JB, van Aken MAG. Childhood personality predicts long-term trajectories of shyness and aggressiveness in the context of demographic transitions in emerging adulthood. Journal of Personality. 2008;76:67–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2007.00480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Unger A, Land K, McCall P, Nagin D. How many latent classes of delinquent/criminal careers? Results from mixed Poisson regression analyses of the London, Philadelphia, and Racine cohort studies. American Journal of Sociology. 1998;103:1593–1630. [Google Scholar]

- Early DM, Rimm-Kaufman SE, Cox MJ, Saluja G, Pianta RC, Bradley RH, Payne CC. Maternal sensitivity and child wariness in the transition to kindergarten. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2002;2:355–377. [Google Scholar]

- Fox NA, Henderson HA, Marshall PJ, Nichols KE, Ghera MM. Behavioral inhibition: linking biology and behavior within a developmental framework. Annual Review of Psychology. 2005;56:235–262. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox NA, Henderson HA, Rubin KH, Calkins SD, Schmidt LA. Continuity and discontinuity of behavioral inhibition and exuberance: Psychophysiological and behavioral influences across the first four years of life. Child Development. 2001;72:1–21. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazelle H. Class climate moderates peer relations and emotional adjustment in children with an early childhood history of anxious solitude: A child x environment model. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:1179–1192. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.6.1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladstone GL, Parker GB, Mitchell PB, Wilhelm KA, Mahli GS. Relationship between self-reported childhood behavioral inhibition and lifetime anxiety disorders in a clinical sample. Depression and Anxiety. 2005;22:103–113. doi: 10.1002/da.20082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady JS, Karraker K, Metzger A. Shyness trajectories in slow-to-warm-up infants: relations with child sex and maternal parenting. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2012;33:91–101. [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA. Perspectives on anxiety and impulsivity: A commentary. Journal of Research in Personality. 1987;21:493–509. [Google Scholar]

- Hane AA, Cheah C, Rubin KH, Fox NA. The role of maternal behavior in the relation between shyness and social withdrawal in early childhood and social withdrawal in middle childhood. Social Development. 2008;17:795–811. [Google Scholar]

- Hane AA, Fox NA, Henderson HA, Marshall PJ. Behavioral reactivity and approach-withdrawal bias in infancy. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:1491–1496. doi: 10.1037/a0012855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshfeld DR, Rosenbaum JF, Biederman J, Bolduc EA, Faraone SV, Snidman N, et al. Stable behavioral inhibition and its association with anxiety disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1992;31:103–111. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199201000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Biederman J, Faraone SV, Violette H, Wrightsman J, Rosenbaum JF. Temperamental correlates of disruptive behavior disorders in young children: preliminary findings. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;50:563–574. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01299-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Biederman J, Henin A, Faraone SV, Cayton GA, Rosenbaum JF. Laboratory-observed behavioral disinhibition in the offspring of parents with bipolar disorder: a high-risk pilot study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:265–271. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.2.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Biederman J, Henin A, Faraone SV, Davis S, Harrington K, Rosenbaum JF. Behavioral inhibition in preschool children at risk is a specific predictor of middle childhood social anxiety: a five-year follow-up. Journal of Developmental Behavioral Pediatrics. 2007;28:225–233. doi: 10.1097/01.DBP.0000268559.34463.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Biederman J, Henin A, Faraone SV, Micco JA, van Grondelle A, Henry B, Rosenbaum JF. Clinical outcomes of laboratory-observed preschool behavioral disinhibition at five-year follow-up. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;62:565–572. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BL, Nagin DS, Roeder K. A SAS procedure based on mixture models for estimating developmental trajectories. Sociological Methods and Research. 2001;29:374–393. [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, Moss HA. Birth to maturity. New York: Wiley; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, Reznick JS, Snidman N. The physiology and psychology of behavioral inhibition in children. Child Development. 1987;58:1459–1473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, Snidman N. Temperamental factors in human development. American Psychologist. 1991;46:856–862. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.46.8.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karevold E, Coplan RJ, Stoolmiller M, Mathiesen KS. A longitudinal study of the links between temperamental shyness, activity, and trajectories of internalizing problems from infancy to middle childhood. Australian Journal of Psychology. 2011;63:36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy SJ, Rapee RM, Edwards SL. A selective intervention program for inhibited preschool-aged children of parents with an anxiety disorder: effects on current anxiety disorders and temperament. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48:602–609. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819f6fa9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letcher P, Smart D, Sanson A, Toumbourou JW. Psychosocial precursors and correlates of differing internalizing trajectories from 3 to 15 years. Social Development. 2009;18:618–646. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Morrarty E, Degnan KA, Chronis-Tuscano A, Rubin KH, Cheah CSL, Pine DS, Henderson HA, Fox NA. Maternal over-control moderates the association between early childhood behavioral inhibition and adolescent social anxiety symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2012;40:1363–1373. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9663-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJ, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Lo Y, Mendell NR, Rubin DB. Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika. 2001;88:767–778. [Google Scholar]

- McCutcheon AL. Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences, Series No 07-064. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1987. Latent class analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Merckelbach H, Wessel I, van de Ven M. Psychopathological correlates of self-reported behavioural inhibition in normal children. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1999;37:575–584. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00155-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, van Brakel AML, Arntz A, Schouten E. Behavioral inhibition as a risk factor for the development of childhood anxiety disorders: a longitudinal study. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2011;20:157–170. doi: 10.1007/s10826-010-9365-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B. Latent variable mixture modeling. In: Marcoulides GA, Schumacker RE, editors. New Developments and Techniques in Structural Equation Modeling. Mawah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2001. pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B. Latent variable analysis: Growth mixture modeling and related techniques for longitudinal data. In: Kaplan D, editor. Handbook of quantitative methodology for the social sciences. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 2004. pp. 345–368. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, Muthén L. Mplus user’s guide. Sixth. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthén BO. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: a monte carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling. 2007;14:535–569. [Google Scholar]

- Oh W, Rubin KH, Bowker JC, Booth-Laforce C, Rose-Krasnor L, Laursen B. Trajectories of social withdrawal from middle childhood to early adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:553–566. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9199-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Edgar K, McDermott JM, Korelitz K, Degnan KA, Curby TW, Pine DS, Fox NA. Patterns of sustained attention in infancy shape the developmental trajectory of social behavior from toddlerhood through adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46:1723–1730. doi: 10.1037/a0021064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. 2. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Burgess KB, Hastings PD. Stability and social-behavioral consequences of toddlers’ inhibited temperament and parenting behaviors. Child Development. 2002;73:483–495. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Coplan RJ, Bowker JC. Social withdrawal in childhood. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:141–171. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Hastings PD, Stewart SL, Henderson HA, Chen X. The consistency and concomitants of inhibition: some of the children, all of the time. Child Development. 1997;68:467–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Krasnor LR. Age and gender differences in solutions to hypothetical social problems. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 1983;4:263–275. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing Data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz CE, Snidman N, Kagan J. Adolescent social anxiety as an outcome of inhibited temperament in childhood. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:1008–1015. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199908000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart S, Rubin KH. The social problem-solving skills of anxious-withdrawn children. Development and Psychopathology. 1995;7:323–336. [Google Scholar]

- Volbrecht MM, Goldsmith HH. Early temperamental and family predictors of shyness and anxiety. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46:1192–1205. doi: 10.1037/a0020616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker OL, Henderson HA, Degnan KA, Fox NA. Social problem-solving in early childhood: Developmental change and the influence of temperament. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2013.04.001. under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White LK, McDermott JM, Degnan KA, Henderson HA, Fox NA. Behavioral inhibition and anxiety: The moderating roles of inhibitory control and attention shifting. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011;39:735–747. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9490-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JJ, McLeod BD, Sigman M, Hwang W, Chu BC. Parenting and childhood anxiety: theory, empirical findings, and future directions. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;44:134–151. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.