Abstract

Objective

To examine prospectively the relationships of prepregnancy body mass index (BMI), BMI at age 18, and weight change since age 18 with risk of fetal loss.

Methods

Our prospective cohort study included 25,719 pregnancies reported by 17,027 women in the Nurses’ Health Study II between 1990 and 2009. In 1989, height, current weight, and weight at age 18 were self-reported. Current weight was updated every 2 years thereafter. Pregnancies were self-reported, with case pregnancies lost spontaneously and comparison pregnancies ending in ectopic pregnancy, induced abortion, or live birth.

Results

Incident fetal loss was reported in 4,494 (17.5%) pregnancies. Compared to those of normal BMI, the multivariate relative risk (RR) (95% confidence interval [CI]) of fetal loss was 1.07 (1.00, 1.15) for overweight women, 1.10 (0.98, 1.23) for class I obese women, and 1.27 (1.11, 1.45) for class II & III obese women (P, trend=<0.001). BMI at age 18 was not associated with fetal loss (P, trend=0.59). Compared to women who maintained a stable weight (+/− 4 kg) between age 18 and before pregnancy, women who lost weight had a 20% (95% CI 9, 29%) lower risk of fetal loss. This association was stronger among women who were overweight at age 18.

Conclusion

Being overweight or obese prior to pregnancy was associated with higher risk of fetal loss. In women overweight or obese at age 18, losing 4 kg or more was associated with a lower risk of fetal loss.

Introduction

It is estimated that one third of pregnancies are lost after implantation (1) and between 11–22% are lost after clinical recognition (2), making pregnancy loss the most frequent adverse pregnancy outcome (3). The effect of obesity on adverse reproductive outcomes is well-recognized (4), including the link between maternal obesity and pregnancy loss (5–9). However, despite the large number of studies, there is no consensus regarding the exact effect of prepregnancy body weight on fetal loss, particularly in spontaneous pregnancies. Studies in the general population tend to lack early pregnancy losses and detailed information on potential confounders since they are based on disease registry data. In contrast, studies in fertility patients have detailed covariate information but tend to be small with limited generalizability. Furthermore, the effect of body weight at younger ages and weight gain since younger ages also remains unclear. Therefore, the aim of this study was to examine the relation between prepregnancy body mass index (BMI), BMI at age 18, and weight change since age 18 and risk of fetal loss in a large, prospective cohort from the general population.

Materials and Methods

The Nurses’ Health Study II is an ongoing prospective cohort of 116,671 female nurses, ages 24 to 44 years at baseline in 1989. Questionnaires are distributed every two years to update lifestyle and medical characteristics and capture incident health outcomes. Follow-up for each questionnaire cycle is greater than 90%. The Nurses’ Health Study II data is a research database that undergoes rigorous quality checks and validation prior to making data accessible for specific analyses. Briefly, questionnaires are checked using coding manuals developed for each specific follow-up cycle. The goal of this check is to code open ended questions, identify potentially erroneous entries and to guarantee that participant’s responses will be able to be captured by the optical scanner.

Women were eligible for this analysis if they had no history of pregnancy loss in 1989 and reported at least one pregnancy during 1990–2009. Eligible participants contributed pregnancies until their first pregnancy loss or the end of follow-up. Women were censored after their first pregnancy loss to prevent reverse causation, that is, behavioral changes in response to an adverse outcome. Of the eligible pregnancies (n=29,860), we excluded from the analysis those with implausible or missing gestation length (n=323), missing year of pregnancy (n=1,233), missing BMI (n=2,247), or with a diagnosis of cardiovascular disease (n=126) or cancer (n=212) prior to pregnancy. The final sample consisted of 25,719 pregnancies from 17,027 women. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Partners Health Care, Boston, Massachusetts, with the participants’ consent implied by the return of the questionnaires.

Prepregnancy weight was self-reported in 1989 and updated every two years thereafter. Height and weight at age 18 were self-reported in 1989. Prepregnancy BMI was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2). To maintain a prospective analysis, BMI information from 1989 was related to pregnancies in 1990 and 1991; the 1991 BMI information was used for pregnancies in 1992 and 1993; and so forth. If a woman reported being pregnant at the time of body weight assessment, the most recent non-pregnant body weight measure was used. BMI at age 18 was calculated as weight at age 18 (kg) divided by height squared (m2). Weight change since age 18 years was calculated as the difference between prepregnancy weight and weight at age 18 years. In a validation study, self-reported height and weight were highly correlated with measured height (r=0.94) and weight (r=0.97)(10). Self-reported weight at age 18 was highly correlated with weight recorded in medical records (r=0.84)(11).

Women were asked to report their pregnancies every two years. In the 2009–2011 questionnaire, women also reported information on the year, length, complications, and outcomes of all previous pregnancies. Options for pregnancy outcomes were a singleton live birth, multiple birth, miscarriage or stillbirth, tubal or ectopic pregnancy, or induced abortion. Options for gestational lengths were <8, 8–11, 12–19, 20–27, 28–31, 32–36, 37–39, 40–42, and 43+ weeks gestation. Because some pregnancy outcomes (e.g. induced abortions) were not recorded prospectively, the prospectively recorded data were combined with the 2009–2011 data to obtain a complete assessment of lifetime pregnancy history. The main outcome in this study was fetal loss defined as either a SAB (<20 completed weeks gestation) or a stillbirth (≥20 completed weeks gestation). The validity of maternal recall of SAB has not been assessed in this population; however the sensitivity of reporting a loss when one actually occurred is estimated to be 75% (12, 13). Non-cases were all pregnancies that did not end in fetal loss (live births, induced abortions, or tubal/ectopic pregnancies).

Information on potential confounders was assessed at baseline and during follow-up. For variables that were updated over follow-up, the most recent value preceding each pregnancy was used. Maternal age was computed as the difference between year of birth and year of pregnancy. Pre-pregnancy physical activity was ascertained in 1989, 1991, 1997, 2001, and 2005. Questionnaire-based physical activity estimates correlated well with detailed activity diaries in a validation study (r=0.56)(14). Pre-pregnancy smoking status, multivitamin use, oral contraceptive use, and history of infertility were self-reported at baseline and updated every two years thereafter. History of ovulation inducing drug use was self-reported in 1993 and updated every 2 years thereafter. Race was reported in 1989. Menstrual cycle length information was reported in 1993. Marital status was reported in 1989, 1993, and 1997.

We divided women into groups according to the World Health Organization BMI classifications for prepregnancy BMI: <18.5 (underweight), 18.5–24.9 (normal weight), 25–29.9 (overweight), 30–34.9 (class I obesity), and 35+ (class II and III obesity). BMI at age 18 was classified in similar categories as prepregnancy BMI; however, due to small numbers, class I–III obesity were combined. Weight change since age 18 was classified into categories based on its distribution in this cohort: lost 4 kg or more, stable weight (+/− 4 kg), gained 4–9.9 kg, gained 10–19.9 kg, and gained 20+ kg. These variables were also analyzed as continuous variables.

The relationships of prepregnancy BMI, BMI at age 18, and weight change since age 18 with fetal loss were estimated using log-binomial regressions. Generalized estimating equations with an exchangeable working correlation structure were used to account for the within-person correlation between pregnancies. Tests for linear trend were conducted by using the median values in each category as a continuous variable. In addition to age-adjusted models, multivariable models were further adjusted for a priori selected prepregnancy covariables: smoking status, physical activity, year of pregnancy, history of infertility, multivitamin use, marital status, and race. Weight change models were further adjusted for height. Categorical covariables included an indicator for missing data, if necessary. Covariables with missing data were smoking status (0.3% missing), physical activity (6% missing), multivitamin use (0.4% missing), and history of infertility (2.8% missing).

Separate analyses were carried out for weight change since age 18 in women with a low BMI (<25) or high BMI (≥25) at age 18. P values for heterogeneity were derived from the cross-product interaction term coefficient added to the main-effects multivariable model. Separate regression models were also used to calculate the relation of BMI with SAB during different gestational windows, all SABs, and stillbirths separately. Non-cases for fetal losses <8 weeks were all initiated pregnancies, non-cases for fetal loses 8–11 weeks were all pregnancies lasting beyond 8 weeks, and so forth. All tests of statistical significance were two-sided and a significance-level of 0.05 was used. All data were analyzed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

This analysis included 17,027 women who contributed 25,719 pregnancies during 20 years of follow-up; 4,494 pregnancies ended in fetal loss (4,289 SABs and 205 stillbirths). On average, participants who were in the highest categories of BMI were older, reported less physical activity, were more likely to be smokers, were more likely to have a history of infertility, ovulation inducing drug use, or long menstrual cycles (>40 days), and were less likely to be nulliparous and current users of oral contraceptives (P<0.05) (Table 1). The correlation between BMI at age 18 and prepregnancy BMI was 0.63.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics of study participants (n= 17,027) by categories of baseline BMI in 1989.

| Prepregnancy BMI Category (Range, kg/m2) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Underweight (< 18.5) | Normal (18.5–24.9) | Overweight (25–29.9) | Obese (≥ 30) | ||

| Number of Women* | 807 | 12,775 | 2388 | 1008 | p-value |

| Maternal Age, n(%) | <0.001 | ||||

| <30 yrs | 425 (52.7) | 5890 (46.1) | 973 (40.8) | 389 (38.6) | |

| 30–34 yrs | 311 (38.5) | 5246 (41.1) | 1048 (43.9) | 443 (44.0) | |

| 35–39 yrs | 66 (8.2) | 1510 (11.8) | 332 (13.9) | 159 (15.8) | |

| 40–44 yrs | 5 (0.6) | 129 (1.0) | 35 (1.5) | 17 (1.7) | |

| Pre-pregnancy Smoking, n(%) | <0.001 | ||||

| Never | 616 (76.3) | 9063 (70.9) | 1643 (68.8) | 675 (67.0) | |

| Former | 103 (12.8) | 2486 (19.5) | 466 (19.5) | 201 (19.9) | |

| Current | 87 (10.8) | 1206 (9.4) | 276 (11.6) | 129 (12.8) | |

| Physical Activity, MET-hrs/week† | 17.4 [7.3–41.1] | 17.7 [7.2–37.6] | 12.9 [5.2–29.1] | 9.9 [3.7–25.7] | <0.001 |

| Multivitamin Use, n(%) | 359 (44.5) | 6194 (48.5) | 1153 (48.3) | 513 (50.9) | 0.25 |

| Ever OC Use | <0.001 | ||||

| Never | 157 (19.5) | 2243 (17.6) | 429 (18.0) | 184 (18.3) | |

| Past | 452 (56.0) | 7064 (55.3) | 1398 (58.5) | 632 (62.7) | |

| Current | 197 (24.4) | 3453 (27.0) | 556 (23.3) | 192 (19.1) | |

| History of Infertility, n(%) | 88 (10.9) | 1538 (12.0) | 342 (14.3) | 173 (17.2) | <0.001 |

| History of Infertility Drug Use‡, n(%) | 95 (11.8) | 1365 (10.7) | 263 (11.0) | 150 (14.9) | 0.002 |

| Married, n(%) | 592 (73.4) | 9555 (74.8) | 1845 (77.3) | 761 (75.5) | 0.05 |

| Caucasian, n(%) | 739 (91.6) | 11886 (93.0) | 2217 (92.8) | 947 (94.0) | 0.26 |

| Parity, n(%) | <0.001 | ||||

| Nulliparous | 448 (55.5) | 6461 (50.6) | 1028 (43.1) | 430 (42.7) | |

| 1 | 201 (24.9) | 3476 (27.2) | 741 (31.0) | 348 (34.5) | |

| 2 | 130 (16.1) | 2163 (16.9) | 440 (18.4) | 162 (16.1) | |

| 3+ | 28 (3.5) | 673 (5.3) | 179 (7.5) | 68 (6.7) | |

| History of Long Menstrual Cycles, n(%) | 35 (4.3) | 494 (3.9) | 117 (4.9) | 71 (7.0) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; MET, metabolic equivalent task; OC, oral contraceptive. Differences across categories were tested using a chi-squared test for categorical variables and Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric tests for continuous variables.

49 eligible women were missing BMI in 1989. Sample sizes may vary due to missing data.

Data are median [25th percentile, 75th percentile].

Question is from 1993 questionnaire (first time it was assessed).

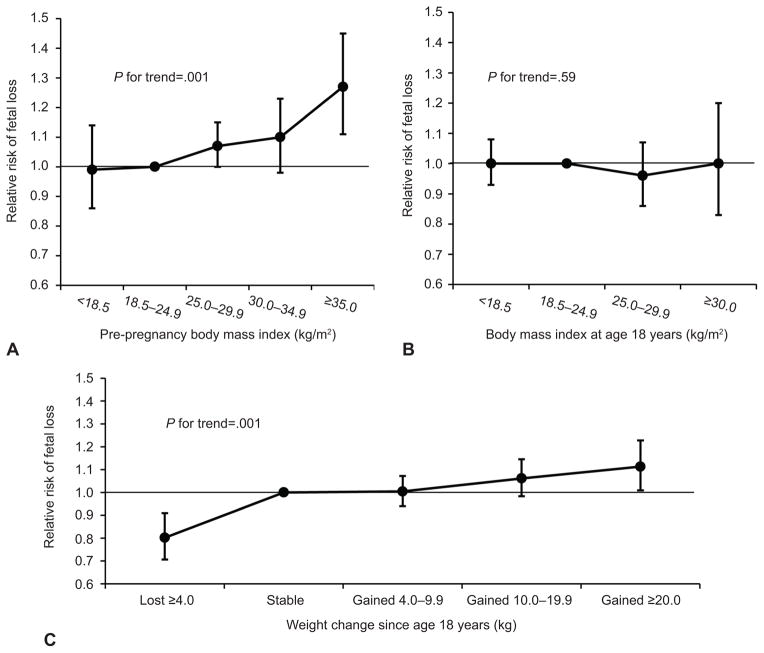

Pre-pregnancy BMI was directly associated with risk of fetal loss (P, trend=<0.001) (Figure 1). For every 2 kg/m2 increase in BMI, the risk of fetal loss increased by 2% (95% CI 1, 3%). Compared to normal weight women, the multivariate adjusted relative risk of fetal loss was 1.07 (95% CI 1.00, 1.15) for overweight women, 1.10 (95% CI 0.98, 1.23) for class I obese women, and 1.27 (95% CI 1.11, 1.45) for class II & III obese women. While BMI at age 18 was unrelated to fetal loss (P, trend=0.59), weight change since age 18 was directly associated with risk of fetal loss. For every 5 kg increase in weight, the risk of fetal loss increased by 3% (95% CI 2, 4%). Compared to women who maintained a stable weight, the multivariate adjusted risk of fetal loss was 20% lower (95% CI −29, −9%) for women who lost 4 kg or more and 11% higher (95% CI 1, 23%) for women who gained ≥ 20 kg (P, trend=<0.001).

Figure 1.

Pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI), BMI at age 18 years, and weight change since age 18 years and relative risks of fetal loss. A. Pre-pregnancy BMI. B. BMI at age 18 years. C. Weight change since age 18 years. All models are adjusted for age (continuous), smoking status (never, former, current, missing), physical activity (< 3.0 MET-h/wk, 3.0–8.9 MET-h/wk, 9.0–17.9 MET-h/wk, 18.0–26.9 MET-h/wk, 27.0–41.9 MET-h/wk, >42.0 MET-h/wk, and missing), year of pregnancy (continuous), history of infertility (no, yes, and missing), current multivitamin use (no, yes, missing), marital status (married, not married), and race (white, other). Weight change models are further adjusted for BMI at age 18 years (continuous). MET-h/wk, metabolic equivalent task hours per week.

To further explore the association of weight gain and risk of fetal loss we stratified the analysis by BMI at age 18 (<25 vs. ≥25 kg/m2) (Table 2). In these models, the association of weight gain with risk of fetal loss was similar in both groups yet only statistically significant in women who had a high BMI (≥25) at age 18. In all models, however, the p-value for interaction failed to reach statistical significance. We also evaluated whether attained prepregnancy BMI mediated the relation between weight gain and fetal loss (Table 2). In models further adjusted for an indicator variable corresponding to whether a woman’s prepregnancy BMI was < 25 kg/m2 or ≥ 25 kg/m2, the risk ratio for a 5 kg weight change was 1.02 (95% CI 1.01, 1.04). These models suggested that attained prepregnancy BMI does not entirely explain the association between weight change since age 18 and fetal loss.

Table 2.

Effect of weight change since age 18 on relative risk (RR) of fetal loss stratified by BMI at age 18.

| Full Population 25,539 pregnancies 16,903 women RR (95% CI) | BMI at Age 18

|

P for Interaction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI < 25 kg/m2 23,398 pregnancies 15,484 women RR (95% CI) | BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 2,141 pregnancies 1,419 women RR (95% CI) | |||

| RR for 5 kg change in body weight from age 18 | ||||

| Model 1: Fully adjusted* | 1.03 (1.02, 1.04) | 1.03 (1.01, 1.04) | 1.04 (1.02, 1.07) | 0.36 |

| Model 2: Fully adjusted + BMI at age 18 | 1.03 (1.02, 1.04) | 1.03 (1.01, 1. 04) | 1.04 (1.02, 1.07) | 0.54 |

| Model 3: Fully adjusted + BMI at age 18 + indicator for prepregnancy overweight/obesity | 1.02 (1.01, 1.04) | 1.02 (0. 99, 1.04) | 1.03 (1.00, 1.07) | 0.49 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; RR, relative risk.

Adjusted for age (continuous), smoking status (never, former, current, missing), physical activity (< 3 MET-h/wk, 3–8.9 MET-h/wk, 9–17.9 MET-h/wk, 18–26.9 MET-h/wk, 27–41.9 MET-h/wk, >42 MET-h/wk, and missing), year of pregnancy (continuous), history of infertility (no, yes, and missing), current multivitamin use (no, yes, missing), marital status (married, not married), race (white, other).

Since SABs and stillbirths are recognized as clinically distinct outcomes, we investigated the effect of body weight on risk of SAB and risk of stillbirth separately. Comparable results were seen for prepregnancy BMI and risk of SAB and stillbirth (Table 3). There were some notable differences for the other relations. Weight gain since age 18 was associated with higher risks of SAB and stillbirth, however, weight loss was associated with a lower risk of SAB (RR 0.78 95% CI 0.68, 0.88) and a statistically non-significant higher risk of stillbirth (RR 1.32 95% CI 0.77, 2.25). Of note, the absolute risk of spontaneous abortion was 2.7 percentage points lower in the women who lost weight compared to those who maintained their weight. In contrast, women who lost weight had only a 0.6 percentage point increase in stillbirth risk compared to women who maintained a stable weight. BMI at age 18 was unrelated to SAB or a higher risk of stillbirth (P, trend=0.06).

Table 3.

Pre-pregnancy BMI, BMI at age 18, and weight change since age 18 and relative risk (RR) of spontaneous abortion and stillbirth.

| Spontaneous Abortions (fetal losses < 20 weeks) | Stillbirths (fetal losses ≥ 20 weeks) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases/Total | % | Fully-Adjusted RR (95% CI)* | Cases/Total | % | Fully-Adjusted RR (95% CI)* | |

| Prepregnancy BMI | ||||||

| Underweight (<18.5 kg/m2) | 159/1037 | 15.3 | 1.01 (0.87, 1.17) | 4/831 | 0.5 | 0.57 (0.21, 1.54) |

| Normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2) | 2945/18348 | 16.1 | 1.00 (REF) | 131/14492 | 0.9 | 1.00 (REF) |

| Overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2) | 781/4282 | 18.2 | 1.07 (1.00, 1.15) | 38/3289 | 1.2 | 1.17 (0.82, 1.68) |

| Class I Obese(30–34.9 kg/m2) | 251/1376 | 18.2 | 1.06 (0.94, 1.18) | 22/1070 | 2.1 | 2.04 (1.30, 3.20) |

| Class II & III Obese (35+ kg/m2) | 153/676 | 22.6 | 1.24 (1.08, 1.43) | 10/475 | 2.1 | 1.99 (1.05, 3.79) |

| P for Trend | 0.004 | < 0.001 | ||||

| BMI at Age 18 | ||||||

| Underweight (<18.5 kg/m2) | 670/3935 | 17.0 | 1.02 (0.94, 1.09) | 23/3087 | 0.8 | 0.73 (0.47, 1.13) |

| Normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2) | 3235/19463 | 16.6 | 1.00 (REF) | 157/15271 | 1.0 | 1.00 (REF) |

| Overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2) | 266/1648 | 16.1 | 0.94 (0.84, 1.06) | 18/1283 | 1.4 | 1.27 (0.78, 2.05) |

| Obese (30+ kg/m2) | 84/493 | 17.0 | 0.98 (0.81, 1.19) | 6/379 | 1.6 | 1.31 (0.58, 2.94) |

| P for Trend | 0.30 | 0.06 | ||||

| Weight Change from Age 18 | ||||||

| Lost ≥ 4 kg | 246/1947 | 12.6 | 0.78 (0.68, 0.88) | 21/1575 | 1.3 | 1.32 (0.77, 2.25) |

| Stable | 1415/8879 | 15.9 | 1.00 (REF) | 60/7047 | 0.9 | 1.00 (REF) |

| Gained 4–9.9 kg | 1389/8332 | 16.7 | 1.01 (0.94, 1.08) | 50/6515 | 0.8 | 0.87 (0.60, 1.27) |

| Gained 10–19.9 kg | 812/4437 | 18.3 | 1.05 (0.97, 1.13) | 46/3438 | 1.3 | 1.37 (0.93, 2.02) |

| Gained ≥ 20 kg | 393/1944 | 20.2 | 1.09 (0.98, 1.20) | 27/1445 | 1.9 | 1.77 (1.11, 2.82) |

| P for Trend | < 0.001 | 0.04 | ||||

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; RR, relative risk.

Models are adjusted for age (continuous), smoking status (never, former, current, missing), physical activity (< 3 MET-h/wk, 3–8.9 MET-h/wk, 9–17.9 MET-h/wk, 18–26.9 MET-h/wk, 27–41.9 MET-h/wk, >42 MET-h/wk, and missing), year of pregnancy (continuous), history of infertility (no, yes, and missing), current multivitamin use (no, yes, missing), marital status (married, not married), and race (white, other). Weight change models are further adjusted for height (continuous).

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the robustness of our findings. The effects of prepregnancy BMI, BMI at age 18, and weight change since age 18 on risk of SAB were estimated separately for first trimester, early second trimester, and late second trimester losses due to potential differences in the underlying etiologies of fetal demise (Appendix 1, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx). For all exposures, the risk of SAB was comparable across different gestational windows. To address the potential of residual confounding due to advanced maternal age, history of infertility, and type II diabetes, we restricted our population to pregnancies less than 40 years, without a history of infertility, and without type II diabetes (Appendix 2, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx). To capture uncontrolled confounding by behaviors related to the recognition of a pregnancy, we restricted analyses to the most likely “pregnancy planners” in our cohort: married women who were currently not using hormonal contraception. Similarly, we restricted our population to only women with regular menstrual cycles to control for the possibility that women with irregular cycles might be less likely to recognize a pregnancy. In all instances, the results remained similar.

Discussion

In this large, prospective cohort of 25,719 pregnancies, we found that the risk of fetal loss was elevated in women who were overweight or obese prior to pregnancy. Weight loss since age 18 was associated with lower risk of fetal loss.

Three meta-analyses have been published in the last 5 years on the relation between prepregnancy BMI and risk of SAB after assisted reproduction (6, 7) and in spontaneous pregnancies (8). There have also been two meta-analyses on BMI and risk of stillbirth (5, 9). While these meta-analyses have found an increased risk of fetal loss in women who are overweight and obese compared to normal weight women, there are important limitations of the individual studies used to generate the pooled results. The majority of studies on prepregnancy BMI and risk of fetal loss are small, retrospective, based on medical records or registry data and thus unable to control for important confounders, and not capable of evaluating the risk of early miscarriage due to late enrollment of women. While our results are consistent with previous literature there are some notable exceptions. First, in contrast to some previous studies (15–18), we found that being overweight was associated with increased risk of fetal loss at < 8 weeks gestation. Therefore the notion that being overweight is possibly a preserving factor in early pregnancy is not supported by our data. Second, we found that being underweight was not associated with increased risk of fetal loss, which is in contrast to many studies (19–22).

Few studies to date have assessed the relation between weight change and risk of fetal loss. A study from Sweden concluded that the adjusted odds of stillbirth were 63% higher in women with inter-pregnancy weight gains of ≥ 3 BMI units compared to those whose weight changed by less than 1 BMI unit (23). Similarly, a US study found that normal-weight mothers who became overweight or obese, overweight mothers who became obese, and obese mothers who stayed obese across the 2 pregnancies under study had increased risk of stillbirth compared with normal-weight mothers who stayed normal-weight (24). Two studies on bariatric surgery and miscarriage rates showed that weight loss after bariatric surgery decreased the risk of subsequent miscarriage (25, 26). All of these findings are in line with our results that adult weight gain is a risk factor for fetal loss, and weight loss could possibly be protective. The only study on weight during early adulthood and risk of miscarriage (27) found no association between overweight or obesity at age 20 and odds of ever having experienced a miscarriage, in agreement with our results on BMI at age 18 and risk of fetal loss.

Multiple biological mechanisms could explain the excess risk of fetal loss associated with greater BMIs and weight gain in adulthood. Relative to normal weight women, the percent of all miscarriages that are aneuploid is lower in overweight women. suggesting that fetal losses in overweight women may be due to factors other than chromosomal abnormalities such as altered hormonal milieu, trophoblastic invasion, and endometrial receptivity (28). Raised BMI has been associated with a variety of endocrine and paracrine changes, which could impair embryonic development and fetoplacental function. These include disturbances in early hormonal milieu (29), altered trophoblastic invasion (30), diminished endometrial receptivity (31), impaired early embryonic development (32), increased insulin resistance (33), increased occurrence of apnea-hypoxia events (34), and hyperlipidemia (35). Pregnancy complications associated with obesity including gestational diabetes, hypertension, and preeclampsia may also mediate the relationship with stillbirth (36).

Unfortunately, we did not have information on gestational weight gain. While possibly a mediating variable, previous studies have shown that adjustment for this factor does not change the association between BMI and fetal loss (37, 38). Second, there is some concern about differential misclassification of fetal loss by gestational age and pregnancy intentions, and that this misclassification might be more common among heavier women. However, our sub-analyses, which stratified on measures of pregnancy intention and recognition found similar results and our sub-analysis which assessed effect modification by gestational age confirmed an association between BMI and fetal loss throughout gestation. Third, despite our adjustment for a variety of confounders, residual confounding is possible, particularly regarding the ability of some women to lose weight. However, differences between unadjusted and multivariate-adjusted effect estimates were small suggesting that residual confounding is unlikely. Fourth, while the Nurses’ Health Study II cohort does not represent random samples of US women, the distribution of prepregnancy BMI was similar to reproductive women in the US (39). Finally, our study does not distinguish chromosomally normal from abnormal miscarriages. Since abnormal miscarriages are likely not susceptible to the effects of environmental exposures this heterogeneity would tend to attenuate our results towards the null.

Our study had several strengths. The large sample size and wide distribution of prepregnancy BMIs conferred ample power to investigate the associations between extreme categories of BMI and risk of fetal loss. Similarly, as a result of having a record of all in-study pregnancies, we had a higher incidence of early SABs in our cohort. This enhanced our power to investigate the association of prepregnancy BMI and early fetal losses. Second, as opposed to many of the previous retrospective, registry-based studies, we had standardized assessment of a wide variety of participant and pregnancy characteristics which increased our ability to adjust for confounding. Finally, the prospective design and nearly-complete follow-up of this cohort over the past 20 years enhanced our ability to draw conclusions regarding the temporality of exposure and outcome and decreased the likelihood of selection bias.

In conclusion, we found dose-response associations of prepregnancy BMI and weight change since age 18 with risk of fetal loss. Given the alarming number of reproductive-aged women who are overweight or obese, clinicians should be aware of the risks of pregnancy loss associated with excess weight.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH grants T32DK007703-16, T32HD060454, and UM1 CA176726.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Treloar AE, Boynton RE, Behn BG, Brown BW. Variation of the human menstrual cycle through reproductive life. Int J Fertil. 1967;12:77–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ammon Avalos L, Galindo C, Li DK. A systematic review to calculate background miscarriage rates using life table analysis. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2012;94:417–23. doi: 10.1002/bdra.23014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bell R, Tennant PWG, Rankin J. Fetal and infance outcomes in obese pregnant women. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2012. pp. 56–69. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siega-Riz AM, Laraia B. The implications of maternal overweight and obesity on the course of pregnancy and birth outcomes. Matern Child Health J. 2006;10:S153–6. doi: 10.1007/s10995-006-0115-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flenady V, Koopmans L, Middleton P, Froen JF, Smith GC, Gibbons K, Coory M, Gordon A, Ellwood D, McIntyre HD, et al. Major risk factors for stillbirth in high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2011;377:1331–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62233-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rittenberg V, Seshadri S, Sunkara SK, Sobaleva S, Oteng-Ntim E, El-Toukhy T. Effect of body mass index on IVF treatment outcome: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Biomed Online. 2011;23:421–39. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2011.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Metwally M, Ong KJ, Ledger WL, Li TC. Does high body mass index increase the risk of miscarriage after spontaneous and assisted conception? A meta-analysis of the evidence. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:714–26. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.07.1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boots C, Stephenson MD. Does obesity increase the risk of miscarriage in spontaneous conception: a systematic review. Semin Reprod Med. 2011;29:507–13. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1293204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chu SY, Kim SY, Lau J, Schmid CH, Dietz PM, Callaghan WM, Curtis KM. Maternal obesity and risk of stillbirth: a metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:223–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Chute CG, Litin LB, Willett WC. Validity of self-reported waist and hip circumferences in men and women. Epidemiol. 1990;1:466–73. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199011000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Troy LM, Hunter DJ, Manson JE, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC. The validity of recalled weight among younger women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1995;19:570–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kristensen P, Irgens LM. Maternal reproductive history: a registry based comparison of previous pregnancy data derived from maternal recall and data obtained during the actual pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79:471–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilcox AJ, Horney LF. Accuracy of spontaneous abortion recall. Am J Epidemiol. 1984;120:727–33. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolf AM, Hunter DJ, Colditz GA, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Corsano KA, Rosner B, Kriska A, Willett WC. Reproducibility and validity of a self-administered physical activity questionnaire. Int J Epidemiol. 1994;23:991–9. doi: 10.1093/ije/23.5.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nohr EA, Bech BH, Davies MJ, Frydenberg M, Henriksen TB, Olsen J. Prepregnancy obesity and fetal death: a study within the Danish National Birth Cohort. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:250–9. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000172422.81496.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Styne-Gross A, Elkind-Hirsch K, Scott RT., Jr Obesity does not impact implantation rates or pregnancy outcome in women attempting conception through oocyte donation. Fertil Steril. 2005;83:1629–34. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.01.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roth D, Grazi RV, Lobel SM. Extremes of body mass index do not affect first-trimester pregnancy outcome in patients with infertility. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:1169–70. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maconochie N, Doyle P, Prior S, Simmons R. Risk factors for first trimester miscarriage--results from a UK-population-based case-control study. BJOG. 2007;114:170–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Veleva Z, Tiitinen A, Vilska S, Hyden-Granskog C, Tomas C, Martikainen H, Tapanainen JS. High and low BMI increase the risk of miscarriage after IVF/ICSI and FET. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:878–84. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Helgstrand S, Andersen AM. Maternal underweight and the risk of spontaneous abortion. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2005;84:1197–201. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2005.00706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Metwally M, Saravelos SH, Ledger WL, Li TC. Body mass index and risk of miscarriage in women with recurrent miscarriage. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:290–5. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tennant PW, Rankin J, Bell R. Maternal body mass index and the risk of fetal and infant death: a cohort study from the North of England. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:1501–11. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Villamor E, Cnattingius S. Interpregnancy weight change and risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes: a population-based study. Lancet. 2006;368:1164–70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69473-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whiteman VE, Crisan L, McIntosh C, Alio AP, Duan J, Marty PJ, Salihu HM. Interpregnancy body mass index changes and risk of stillbirth. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2011;72:192–5. doi: 10.1159/000324375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friedman D, Cuneo S, Valenzano M, Marinari GM, Adami GF, Gianetta E, Traverso E, Scopinaro N. Pregnancies in an 18-Year Follow-up after Biliopancreatic Diversion. Obes Surg. 1995;5:308–313. doi: 10.1381/096089295765557692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bilenka B, Ben-Shlomo I, Cozacov C, Gold CH, Zohar S. Fertility, miscarriage and pregnancy after vertical banded gastroplasty operation for morbid obesity. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1995;74:42–4. doi: 10.3109/00016349509009942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jacobsen BK, Knutsen SF, Oda K, Fraser GE. Obesity at age 20 and the risk of miscarriages, irregular periods and reported problems of becoming pregnant: the Adventist Health Study-2. Eur J Epidemiol. 2012;27:923–31. doi: 10.1007/s10654-012-9749-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kroon B, Harrison K, Martin N, Wong B, Yazdani A. Miscarriage karyotype and its relationship with maternal body mass index, age, and mode of conception. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:1827–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.11.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pasquali R, Gambineri A. Metabolic effects of obesity on reproduction. Reprod Biomed Online. 2006;12:542–51. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)61179-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palomba S, Russo T, Falbo A, Di Cello A, Amendola G, Mazza R, Tolino A, Zullo F, Tucci L, La Sala GB. Decidual endovascular trophoblast invasion in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: an experimental case-control study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:2441–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Metwally M, Tuckerman EM, Laird SM, Ledger WL, Li TC. Impact of high body mass index on endometrial morphology and function in the peri-implantation period in women with recurrent miscarriage. Reprod Biomed Online. 2007;14:328–34. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60875-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang TH, Chang CL, Wu HM, Chiu YM, Chen CK, Wang HS. Insulin-like growth factor-II (IGF-II), IGF-binding protein-3 (IGFBP-3), and IGFBP-4 in follicular fluid are associated with oocyte maturation and embryo development. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:1392–401. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.03.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Craig LB, Ke RW, Kutteh WH. Increased prevalence of insulin resistance in women with a history of recurrent pregnancy loss. Fertil Steril. 2002;78:487–90. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)03247-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coletta J, Simpson LL. Maternal medical disease and stillbirth. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2010;53:607–16. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e3181eb2ca0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Germain AM, Romanik MC, Guerra I, Solari S, Reyes MS, Johnson RJ, Price K, Karumanchi SA, Valdes G. Endothelial dysfunction: a link among preeclampsia, recurrent pregnancy loss, and future cardiovascular events? Hypertension. 2007;49:90–5. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000251522.18094.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simpson LL. Maternal medical disease: risk of antepartum fetal death. Semin Perinatol. 2002;26:42–50. doi: 10.1053/sper.2002.29838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cnattingius S, Bergstrom R, Lipworth L, Kramer MS. Prepregnancy weight and the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:147–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801153380302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stephansson O, Dickman PW, Johansson A, Cnattingius S. Maternal weight, pregnancy weight gain, and the risk of antepartum stillbirth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:463–9. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.109591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kuczmarski RJ, Johnson CL. Overweight and obesity in the United States: prevalence and trends, 1960–1994. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1998;22:39–47. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.