Abstract

Objectives

Urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) is upregulated during inflammation and known to bind to β3-integrins, receptors used by pathogenic hantaviruses to enter endothelial cells. It has been proposed that soluble uPAR (suPAR) is a circulating factor that causes focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and proteinuria by activating β3-integrin in kidney podocytes. Proteinuria is also a characteristic feature of hantavirus infections. The aim of this study was to evaluate the relation between urine suPAR levels and disease severity in acute Puumala hantavirus (PUUV) infection.

Design

A single-centre, prospective cohort study.

Subjects and methods

Urinary suPAR levels were measured twice during the acute phase and once during convalescence in 36 patients with serologically confirmed PUUV infection. Fractional excretion of suPAR (FE suPAR) and of albumin (FE alb) were calculated.

Results

The FE suPAR was significantly elevated during the acute phase of PUUV infection compared to the convalescent phase (median 3.2%, range 0.8–52.0%, vs. median 1.9%, range 1.0–5.8%, P = 0.005). Maximum FE suPAR was correlated markedly with maximum FE alb (r = 0.812, P < 0.001), and with several other variables that reflect disease severity. There was a positive correlation with the length of hospitalization (r = 0.455, P = 0.009) and maximum plasma creatinine level (r = 0.780, P < 0.001), and an inverse correlation with minimum urinary output (r = −0.411, P = 0.030). There was no correlation between FE suPAR and plasma suPAR (r = 0.180, P = 0.324).

Conclusion

Urinary suPAR is markedly increased during acute PUUV infection and is correlated with proteinuria. High urine suPAR level may reflect local production of suPAR in the kidney during the acute infection.

Keywords: acute kidney injury, hantavirus, soluble urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor, suPAR, tubulointerstitial nephritis

Introduction

Haemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS) and hantavirus cardiopulmonary syndrome (HCPS) are the two types of diseases caused by hantaviruses in humans [1–3]. HFRS occurs in Europe and Asia, and HCPS in North and South America [1–3]. There are similarities in the clinical features of HFRS and HCPS, and the symptoms overlap [4–5]. Puumala hantavirus (PUUV) is the most common cause of HFRS in Europe, and the majority of cases are reported in Finland [6]. During recent years, the annual number of serological diagnoses of PUUV infection has been approximately 1000–3000 in Finland [7]. Although PUUV infection most often causes a mild type of HFRS with a low mortality rate of approximately 0.1%, the infection often leads to hospitalization and in some cases intensive care unit treatment with haemodialysis may be required during the acute phase [8].

Common symptoms of PUUV infection include sudden high fever, headache, abdominal and back pain, nausea and visual disturbances [9–12]. Severe haemorrhage is rare, but mild bleeding manifestations occur in about one-third of patients [11]. Renal involvement causes transient, sometimes massive, proteinuria, microscopic haematuria and oliguria, which is followed by polyuria and spontaneous recovery [9–12]. Haemodialysis treatment is needed during the oliguric phase for up to 6% of hospitalized patients [10–12]. The distinctive histopathological renal finding in PUUV infection is acute tubulointerstitial nephritis, and the infiltrating cells include lymphocytes, plasma cells, monocytes, macrophages and polymorphonuclear cells [13–14]. Glomerular changes are mild and do not correlate with the amount of proteinuria [13]. Typical laboratory findings include leukocytosis, thrombocytopenia, anaemia and elevation of plasma C-reactive protein (CRP) and creatinine levels, as well as proteinuria and haematuria [10–11, 13]. Host genetics have been shown to influence the clinical picture [15–16].

The pathogenesis of PUUV as well as of other hantavirus infections is not completely understood. The endothelial cells of the post-capillary venules in various organs are considered the primary targets of hantavirus infection, with cellular entry mediated by β3-integrins [17–21]. However, there do not seem to be any widespread cytopathic effects on the endothelium, suggesting that the disease is caused by indirect mechanisms [19–21].

Urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) is attached to the cell membrane by a glycolipid (glycosylphosphatidylinositol, GPI, anchor). When urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) is bound to its receptor, cleavage occurs and soluble uPAR (suPAR) is released. uPAR is a glycoprotein upregulated during infection and inflammation and is involved in many different immune functions [22–23]. uPAR is expressed in numerous cells, including monocytes, lymphocytes, neutrophils, malignant cells, endothelial cells and kidney tubular epithelial cells as well as podocytes [22–25]. uPAR and its ligand uPA promote the migration and adhesion of leukocytes by binding to β-integrins [22]. Plasma levels of suPAR reflect the activation level of the immune and inflammatory systems [23]. It has been shown that plasma suPAR is increased and has prognostic value in predicting disease severity and outcome in various conditions, such as autoimmune diseases, cancer and bacterial, parasitic and viral infections [23, 26–32]. It has also been reported that plasma suPAR is a risk marker of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes and mortality in the general population, probably reflecting low-grade inflammation [33]. Circulating suPAR levels are also elevated in a large number of patients with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) [34]. It has been proposed that suPAR is a circulating factor that causes proteinuria and initiation of FSGS by activating β3-integrin, the receptor for cellular entry of pathogenic hantaviruses, in kidney podocytes [35]. suPAR has also been found in the urine of healthy individuals and patients with various clinical disorders [24–25, 36–39].

Recently, we found that plasma suPAR levels were elevated and predicted disease severity in acute PUUV infection [40]. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the associations between urine suPAR and the severity of acute PUUV infection, especially with regard to proteinuria. A secondary aim was to assess the possible role of suPAR in the pathogenesis of proteinuria in PUUV infection.

Materials and methods

Patients

The study cohort consisted of 36 prospectively collected consecutive adult patients with acute PUUV infection. The diagnosis of acute PUUV infection was made on presentation by a positive rapid anti-PUUV IgM test (POC® PUUMALA IgM, Reagena Ltd, Toivala, Finland) and later confirmed by an anti-PUUV IgM enzyme immunoassay test (Reagena Ltd) in all cases [41]. Patients were treated at the Tampere University Hospital (Tampere, Finland) from January 2005 to March 2007. The median patient age was 45 (range 22−77) years, and 24 (67%) were male. The patients in the present study have also participated in our previous studies investigating the effects of levels of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) [42], GATA-3 [43] and plasma suPAR [40] in PUUV infection.

All subjects provided written informed consent before participation and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tampere University Hospital.

Study protocol

All 36 patients were examined during the acute phase of PUUV infection. A detailed past and current medical history was obtained, and a careful physical examination was performed. Blood samples were collected, between 7:30 and 9:30 in the morning for 2 consecutive weekdays after hospitalization, for the analysis of plasma suPAR. Blood samples for the determination of plasma CRP, interleukin (IL)-6, creatinine and albumin (alb) concentrations, serum IDO concentration and blood cell counts were collected for up to 5 consecutive days. Other blood samples were collected according to the clinical needs of the patient. Urine samples for the determination of suPAR, creatinine, alb and IL-6 concentrations were collected on the same morning as the respective blood samples. The highest and lowest values of the various variables measured during hospitalization for each patient were designated as the maximum and minimum values, respectively.

Overall, 33 (92%) patients returned to the outpatient clinic 1–3 weeks after the period of hospitalization. The plasma and urine samples collected at the outpatient clinic after hospital treatment were regarded as convalescent (control) samples.

Urine and plasma sample analyses

Urine and plasma samples for suPAR determination were collected from patients during hospitalization and at the outpatient clinic visit and stored at −70 °C until required for analysis. Urine and plasma suPAR levels were determined using a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (suPARnostic® Standard kit; ViroGates A/S, Birkerød, Denmark) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Plasma CRP, creatinine and alb levels were analysed using the Cobas Integra analyser (F. Hoffman-La Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland). Blood cell count was determined using haematology cell counters (Bayer, Leverkusen, Germany). IDO levels were measured by determining the ratio of kynurenine to tryptophan in serum [44] by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography, as previously described [45]. Plasma suPAR, CRP and creatinine concentrations, blood cell count and the level of urine suPAR were determined at the Laboratory Centre of Pirkanmaa Hospital District and at the Fimlab Laboratories, Tampere, Finland. Urine creatinine and alb concentrations, as well as plasma alb levels were determined at the University of Massachusetts Memorial HealthCare Hospital Laboratories using standard methods. A concentration of urinary alb below the detection limit of the assay (6 mg/dL) was regarded as 6 mg/dL in calculations. Plasma and urine IL-6 concentrations were determined on a Bio-Plex Luminex-100 station at the Baylor NIAID Luminex Core Facility (Dallas, TX, USA) using standard methods. R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN) Luminex reagents were used.

The fractional excretion of a protein (FE protein) was calculated using the equation: FE protein=(P creatinine × U protein) / (P protein × U creatinine) %, where U is urinary concentration and P is plasma concentration [46]. Only values from plasma and urine collected on the same day were used in the calculations.

Statistical analyses

The data are presented as medians and ranges for continuous variables and numbers and percentages for categorical variables. Groups were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. Correlations were calculated by the Spearman’s rank correlation test. Wilcoxon’s test was used to compare two related samples. All tests were two-sided, and all P-values are given. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. The SPSS (version 20) statistical software package (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all analyses.

Results

The clinical characteristics and laboratory data of the patients are shown in Table 1. The median duration of fever before hospital admission was 4 (range 2–9) days. One patient needed dialysis during hospitalization. None of the patients was in clinical shock on admission and no deaths occurred.

Table 1.

Clinical and laboratory data of 36 patients with acute Puumala hantavirus infection

| Median | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 45 | 22–74 |

| Duration of fever (days) | 8 | 4–15 |

| Length of hospitalization (days) | 6 | 2–10 |

| Change in weight during hospitalization (kg)* | 1.9 | 0–10.8 |

| Urinary output, min (mL/day) | 1180 | 100–3190 |

| Plasma creatinine, max (µmol/L) | 173 | 52–1071 |

| Plasma alb, min (g/L) | 25 | 10–37 |

| Platelets, min (109/L) | 53 | 21–113 |

| Haematocrit, min | 0.36 | 0.30–0.40 |

| Blood leukocytes, max (109/L) | 9.9 | 5.6–24.0 |

| Plasma suPAR, max (ng/mL) | 8.5 | 4.1–14.9 |

| Urine suPAR, max (ng/mL) | 12.8 | 4.9–37.0 |

| Plasma CRP, max (mg/L) | 92.3 | 15.9–176.0 |

| Serum IDO, max (µmol/mmol) | 176 | 64–552 |

| Plasma IL-6, max (µg/mL) | 24.0 | 10.0–917.1 |

| Fractional excretion of IL-6, max (%) | 5.16 | 0.04–419.10 |

Reflects fluid retention during the oliguric phase.

Alb, albumin; CRP, C-reactive protein; suPAR, soluble urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor; IDO, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase; min, minimum value; max, maximum value.

The FE suPAR was significantly elevated during the acute phase of PUUV infection compared to the control convalescent phase (Table 2). The FE alb and the urine alb/creatinine ratio were also significantly elevated during the acute phase (Table 2). The control values were obtained a median of 22 (range 17–32) days after the onset of fever.

Table 2.

Uriine alb/crea ratios and FE suPAR and FE alb values during the acute (Maximum) and convalescent (Control) phases in 36 patients with acute Puumala hantavirus-induced tubulointerstitial nephritis

| Maximum | Control | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FE suPAR (%) | 3.2 (0.8–52.0) | 1.9 (1.0–5.8) | 0.005 |

| Urine alb/crea (g/mol) | 108 (18–1647) | 11 (5–48) | <0.001 |

| FE alb (%) | 0.1026 (0.0050–1.9385) | 0.0026 (0.0008–0.0151) | <0.001 |

The data are presented as median (range).

suPAR, soluble urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor; crea, creatinine; alb, albumin; FE, fractional excretion of protein.

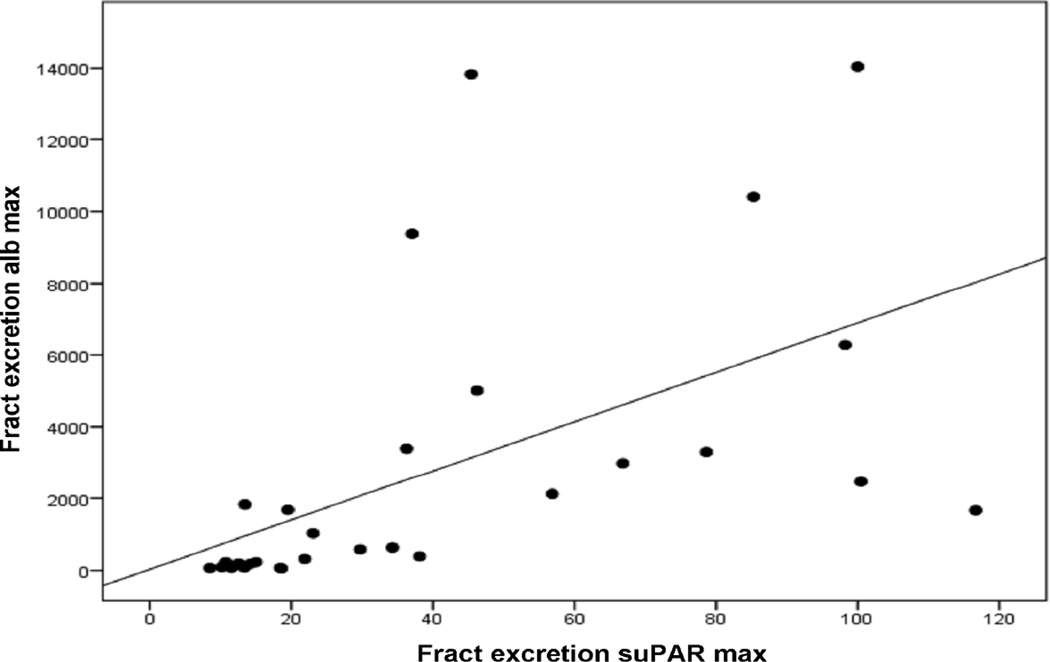

The maximum FE suPAR was correlated markedly with maximum FE alb (Fig. 1). There was also a positive correlation between maximum FE suPAR and maximum urine alb/creatinine ratio (Table 3). A significant correlation was also found between maximum FE suPAR and several other parameters reflecting the severity of PUUV infection (Table 3). There was a positive correlation with maximum plasma creatinine level, change in body weight during hospitalization, duration of hospitalization and maximum blood leukocyte count. FE suPAR was also correlated positively with maximum FE IL-6 and the maximum serum IDO level. There was a negative correlation with the minimum urinary output and the minimum haematocrit. However, there was no correlation between maximum FE suPAR and maximum plasma CRP or IL-6 levels, minimum plasma alb or minimum platelet count. Finally, there was no correlation between maximum FE suPAR and maximum plasma suPAR levels (Table 3). The maximum FE suPAR was not correlated with age (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Correlation between maximum fractional excretion of soluble urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (fract excretion suPAR max) and maximum fractional excretion of albumin (fract excretion alb max) in 34 patients with acute Puumala hantavirus-induced nephritis (r = 0.812, P < 0.001). Two outliers have not been presented on the figure.

Table 3.

Correlations between maximum fractional excretion of suPAR and clinical and laboratory variables in 36 patients with Puumala hantavirus infection

| r | P-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Duration of hospital care | 0.455 | 0.009 |

| Change in weight during hospitalization* | 0.652 | <0.001 |

| Urinary output, min | −0.411 | 0.030 |

| Plasma crea, max | 0.780 | <0.001 |

| FE alb, max | 0.812 | <0.001 |

| Urine alb/crea, max | 0.619 | <0.001 |

| Plasma alb, min | −0.202 | 0.267 |

| Platelets, min | 0.204 | 0.262 |

| Haematocrit, min | −0.411 | 0.019 |

| Blood leukocytes, max | 0.496 | 0.004 |

| Plasma suPAR, max | 0.180 | 0.324 |

| Plasma CRP, max | −0.181 | 0.322 |

| Serum IDO, max | 0.669 | <0.001 |

| Plasma IL-6, max | 0.175 | 0.338 |

| FE IL-6, max | 0.735 | <0.001 |

Reflects fluid retention during the oliguric phase.

suPAR, soluble urokinase-type plasminogen activator; FE, fractional excretion of protein; alb, albumin; crea, creatinine; CRP, C-reactive protein; IDO, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase min, minimum value; max, maximum value.

Discussion

In the present study we have shown that urinary suPAR is elevated in acute hantavirus infection caused by PUUV. The acute-phase FE values were significantly higher than values during the convalescent phase. Furthermore, the maximum FE suPAR correlated with several parameters reflecting disease severity. Most importantly, the maximum FE suPAR was correlated with signs of proteinuria (i.e. FE alb and urine alb/creatinine ratio). FE suPAR was also correlated positively with plasma creatinine level. However, this correlation may be influenced by the fact that the plasma creatinine value was included in the equation to calculate FE suPAR (see above). A positive correlation was also found with change in body weight, which reflects fluid retention during the oliguric phase, and a negative correlation with minimum urinary output. The maximum FE suPAR was also correlated with the maximum FE IL-6; the urinary excretion of this cytokine is correlated with proteinuria in PUUV-infected patients [47]. Moreover, the maximum FE suPAR correlated with IDO, a biomarker that has been shown to be an independent risk factor for significant renal insufficiency in acute PUUV infection [42]. FE suPAR and plasma suPAR levels were not correlated in the present study.

Previously, suPAR has been found in the urine of healthy individuals, cancer patients, renal transplant recipients, patients with urosepsis and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients [24–25, 36–39, 48–52]. Urine suPAR levels have been reported to be elevated in patients with various malignancies, including acute myeloid leukemia (AML), bladder, pancreatic and breast cancer and gynaecological malignancies [36–37, 39, 48–50]. Furthermore, urine suPAR levels decreased during chemotherapy in AML patients, and demonstrated prognostic value in patients with pancreatic cancer [37, 39]. In HIV, the only viral infection for which the association with urine suPAR concentration has been previously reported, levels of suPAR predicted risk of mortality [38]. Urine uPAR levels were elevated in renal transplant recipients, and were higher in patients who rejected, compared to those who did not reject their transplant [25]. Moreover, urine suPAR levels correlated with serum creatinine levels in patients with acute renal allograft rejection [25].

Urine suPAR levels have previously been found to strongly correlate with plasma suPAR levels [36–38, 51]. However, in the present study, there was no correlation between FE suPAR and plasma suPAR levels. Previously, in patients with urosepsis, plasma and urine suPAR levels were both found to be elevated, but there was a lack of correlation between them, suggesting local production in the kidney [24]. Damaged tubuli were shown to strongly express uPAR during acute pyelonephritis [24]. During acute kidney allograft rejection, uPAR is also upregulated in kidney biopsies and produced by inflammatory cells, tubular epithelial cells and vascular endothelial cells [25]. uPAR expression has also been observed in the tubular epithelium in normal renal tissue [53]. Thus, tubular epithelial cells express low levels of uPAR under normal conditions and this expression is upregulated by inflammation [24].

FSGS is a chronic glomerulonephritis that leads to proteinuria, nephrotic syndrome and often end-stage renal disease. It can recur rapidly after renal transplantation, which has led to speculation of the existence of a circulating permeability factor that causes FSGS [54–55]. FSGS is known to be due to damage to the kidney glomerulus podocytes [55]. The major functions of podocytes are to limit the passage of alb from the circulation into the urine and to maintain glomerular integrity [55]. β3-integrins, in turn, anchor podocytes to the underlying glomerular basement membrane [55]. It has been shown that suPAR is able to activate podocyte β3-integrins in the glomeruli, thus causing podocyte dysfunction and foot process effacement, resulting in proteinuria [35]. The majority of patients with FSGS have elevated circulating suPAR levels [34–35]. As such, it has been suggested that suPAR may be the circulating factor causing FSGS [35]. Recently, it has been proposed that urinary suPAR may be useful in predicting the recurrence of FSGS in renal transplant recipients [56].

Proteinuria is the most common finding in the urinalysis of PUUV-infected patients; it is detected in almost all patients, and is in the nephrotic range in up to one-third [9–12, 47]. The pathogenesis of this considerable protein excretion is unclear. Although tubular injury contributes to the proteinuria, as evidenced by the loss of low-molecular weight proteins, the nonselective nature of the proteinuria also indicates a defective glomerular barrier [20]. However, only minor histological glomerular alterations are seen in PUUV infection [13]. Moreover, no relation has been demonstrated between the severity of the histological changes and the degree of protein excretion [13]. Besides vascular endothelial cells, hantaviruses can also infect tubular cells, glomerular endothelial cells and podocytes of the human kidney, disrupting cell-to-cell contacts in all of these cell types [57]. This disruption can decrease the barrier functions of the kidney, and therefore directly cause proteinuria. In addition, in some kidney epithelial cell lines, apoptosis has been reported in response to hantavirus infection [58–59].

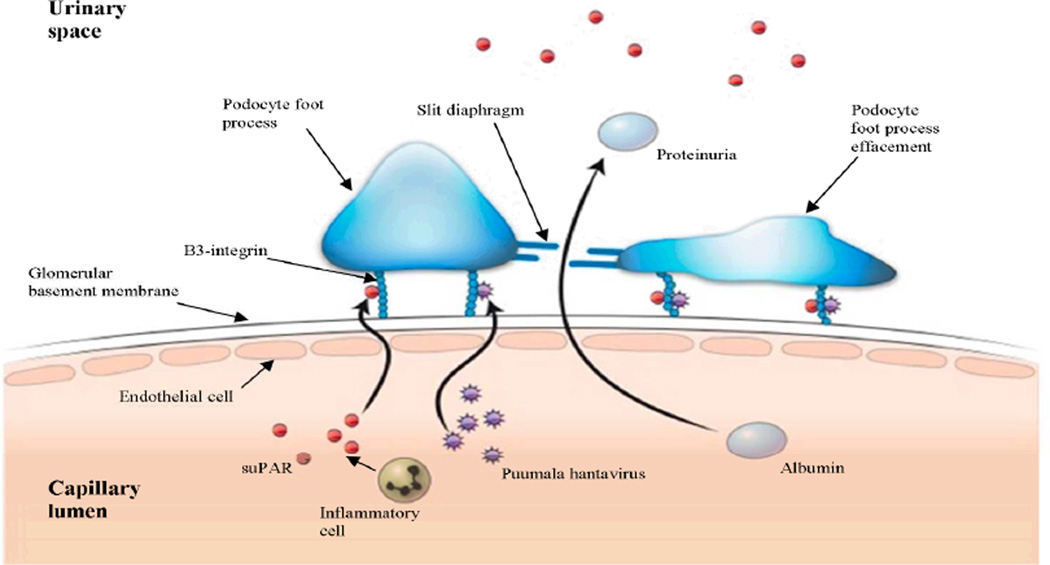

In the present study we found that the maximum FE suPAR during the acute phase of PUUV infection strongly correlated with proteinuria. Taking into account the role of suPAR in the initiation of proteinuria in FSGS, it is possible that suPAR has a pathogenetic role in the proteinuria observed in PUUV infection. suPAR could produce disruption of kidney barrier functions in PUUV infection by activating podocyte β3-integrins, receptors that are also pivotal for the entry of hantaviruses, thus producing foot process effacement and proteinuria. Indeed, fusion of the foot processes has previously been found in electron microscopic studies of PUUV-infected kidneys [60–61]. In addition to the lack of correlation between the FE suPAR and plasma suPAR levels mentioned above, the FE suPAR was also markedly higher than the FE alb (3.2% vs. 0.1%) although the molecular weight of both proteins is almost equal (60 kDa and 66 kDa, respectively) and they are therefore probably handled in the same way in the kidney [23]. These findings may indicate that suPAR is produced locally in the kidney. Previous findings of upregulated suPAR expression by tubular epithelial cells during inflammation in tubulointerstitial nephritides, such as pyelonephritis and renal allograft rejection, support this assumption [24–25]. It is noteworthy that inflammatory cells known to express suPAR have been found in the interstitium of PUUV-infected kidney [13]. Furthermore, high urinary IL-6 levels have previously been found, possibly reflecting local production of this cytokine in the kidneys [47]. However, the involvement of tubular dysfunction in the urinary excretion of suPAR cannot be ruled out. Fig. 2 shows a schematic diagram of the proposed involvement of suPAR in the development of proteinuria in PUUV hantavirus infection.

Fig. 2.

Schematic diagram of the proposed role of soluble urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR) in the development of proteinuria in Puumala hantavirus (PUUV) infection. suPAR and PUUV activate podocyte β3-integrins resulting in foot process effacement and loss of slit diaphragm, thus producing disruption of kidney barrier functions and proteinuria. It is likely that circulating suPAR is involved but also that local production of suPAR in the kidney has a role as inflammatory cells known to produce suPAR have been found in the interstitium of PUUV-infected kidney. suPAR may also be released from the urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor expressed by glomerular endothelial cells and podocytes.

In conclusion, urinary suPAR levels are enhanced in acute PUUV infection and the FE suPAR correlates with the degree of proteinuria. The absence of a correlation between urinary suPAR and plasma suPAR levels as well as the higher FE of suPAR than alb suggest the possible local production of suPAR in the kidney. It is possible that suPAR may have a pathogenetic role in the proteinuria that is observed during PUUV hantavirus infection.

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by the Competitive State Research Financing of the Expert Responsibility Area of Tampere University Hospital (9P031, Fimlab X50000), European Commission Project ‘Diagnosis and control of rodent-borne viral zoonoses in Europe‘ (QLK2-CT-2002-01358) and by grants from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIH/NIAID) (U19 AI57319), the Academy of Finland, the Sigrid Jusélius Foundation, the Finnish Kidney Foundation and the Orion-Farmos Research Foundation.

We thank Professor Amos Pasternack for his expertise and valuable advice, which we greatly appreciate. We also thank Heini Huhtala for statistical advice. We are grateful for the skillful technical assistance of Ms Katriina Ylinikkilä, Ms Eini Eskola and Ms Mirja Ikonen.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

None of the authors has any conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Vaheri A, Henttonen H, Voutilainen L, Mustonen J, Sironen T, Vapalahti O. Hantavirus infections in Europe and their impact on public health. Rev Med Virol. 2013;23:35–49. doi: 10.1002/rmv.1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vapalahti O, Mustonen J, Lundkvist Å, Henttonen H, Plyusnin A, Vaheri A. Hantavirus infections in Europe. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3:653–661. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(03)00774-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vaheri A, Strandin T, Hepojoki J, Sironen T, Henttonen H, Makela S, Mustonen J. Uncovering the mysteries of hantavirus infections. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013;11:539–550. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clement J, Maes P, Lagrou K, Van Ranst M, Lameire N. A unifying hypothesis and a single name for a complex globally emerging infection: hantavirus disease. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;31:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1456-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rasmuson J, Andersson C, Norrman E, Haney M, Evander M, Ahlm C. Time to revise the paradigm of hantavirus syndromes? Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome caused by European hantavirus. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;30:685–690. doi: 10.1007/s10096-010-1141-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heyman P, Vaheri A. Situation of hantavirus infections and haemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome in European countries as of December 2006. Euro Surveill. 2008;13 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. http://www3.thl.fi/stat/

- 8.Makary P, Kanerva M, Ollgren J, Virtanen MJ, Vapalahti O, Lyytikäinen O. Disease burden of Puumala virus infections, 1995–2008. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138:1484–1492. doi: 10.1017/S0950268810000087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lähdevirta J. Nephropathia epidemica in Finland. A clinical histological and epidemiological study. Ann Clin Res. 1971;3:1–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mustonen J, Brummer-Korvenkontio M, Hedman K, Pasternack A, Pietilä K, Vaheri A. Nephropathia epidemica in Finland: a retrospective study of 126 cases. Scand J Infect Dis. 1994;26:7–13. doi: 10.3109/00365549409008583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Settergren B, Juto P, Trollfors B, Wadell G, Norrby SR. Clinical characteristics of nephropathia epidemica in Sweden: prospective study of 74 cases. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11:921–927. doi: 10.1093/clinids/11.6.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braun N, Haap M, Overkamp D, Kimmel M, Alscher MD, Lehnert H, Haas CS. Characterization and outcome following Puumala virus infection: a retrospective analysis of 75 cases. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:2997–3003. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mustonen J, Helin H, Pietilä K, Brummer-Korvenkontio M, Hedman K, Vaheri A, Pasternack A. Renal biopsy findings and clinicopathologic correlations in nephropathia epidemica. Clin Nephrol. 1994;41:121–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Temonen M, Mustonen J, Helin H, Pasternack A, Vaheri A, Holthöfer H. Cytokines, adhesion molecules, and cellular infiltration in nephropathia epidemica kidneys: an immunohistochemical study. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1996;78:47–55. doi: 10.1006/clin.1996.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mustonen J, Partanen J, Kanerva M, Pietilä K, Vapalahti O, Pasternack A, Vaheri A. Genetic susceptibility to severe course of nephropathia epidemica caused by Puumala hantavirus. Kidney Int. 1996;49:217–221. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mäkelä S, Mustonen J, Ala-Houhala I, et al. Human leukocyte antigen-B8-DR3 is a more important risk factor for severe Puumala hantavirus infection than the tumor necrosis factor-alpha(-308) G/A polymorphism. J Infect Dis. 2002;186:843–846. doi: 10.1086/342413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gavrilovskaya IN, Shepley M, Shaw R, Ginsberg MH, Mackow ER. beta3 Integrins mediate the cellular entry of hantaviruses that cause respiratory failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:7074–7079. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.7074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gavrilovskaya IN, Brown EJ, Ginsberg MH, Mackow ER. Cellular entry of hantaviruses which cause hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome is mediated by beta3 integrins. J Virol. 1999;73:3951–3959. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.3951-3959.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zaki SR, Greer PW, Coffield LM, et al. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. Pathogenesis of an emerging infectious disease. Am J Pathol. 1995;146:552–579. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cosgriff TM. Mechanisms of disease in Hantavirus infection: pathophysiology of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13:97–107. doi: 10.1093/clinids/13.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kanerva M, Mustonen J, Vaheri A. Pathogenesis of Puumala and other hantavirus infections. Rev Med Virol. 1998;8:67–86. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1654(199804/06)8:2<67::aid-rmv217>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ossowski L, Aguirre-Ghiso JA. Urokinase receptor and integrin partnership: coordination of signaling for cell adhesion, migration and growth. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2000;12:613–620. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00140-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thuno M, Macho B, Eugen-Olsen J. suPAR: the molecular crystal ball. Dis Markers. 2009;27:157–172. doi: 10.3233/DMA-2009-0657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Florquin S, van den Berg JG, Olszyna DP, Claessen N, Opal SM, Weening JJ, van der Poll T. Release of urokinase plasminogen activator receptor during urosepsis and endotoxemia. Kidney Int. 2001;59:2054–2061. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roelofs JJ, Rowshani AT, van den Berg JG, et al. Expression of urokinase plasminogen activator and its receptor during acute renal allograft rejection. Kidney Int. 2003;64:1845–1853. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eugen-Olsen J, Gustafson P, Sidenius N, et al. The serum level of soluble urokinase receptor is elevated in tuberculosis patients and predicts mortality during treatment: a community study from Guinea-Bissau. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2002;6:686–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huttunen R, Syrjänen J, Vuento R, et al. Plasma level of soluble urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor as a predictor of disease severity and case fatality in patients with bacteraemia: a prospective cohort study. J Intern Med. 2011;270:32–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2011.02363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koch A, Voigt S, Kruschinski C, et al. Circulating soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor is stably elevated during the first week of treatment in the intensive care unit and predicts mortality in critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2011;15:R63. doi: 10.1186/cc10037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mölkänen T, Ruotsalainen E, Thorball CW, Järvinen A. Elevated soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR) predicts mortality in Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;30:1417–1424. doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1236-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sidenius N, Sier CF, Ullum H, Pedersen BK, Lepri AC, Blasi F, Eugen-Olsen J. Serum level of soluble urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor is a strong and independent predictor of survival in human immunodeficiency virus infection. Blood. 2000;96:4091–4095. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ostrowski SR, Ullum H, Goka BQ, et al. Plasma concentrations of soluble urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor are increased in patients with malaria and are associated with a poor clinical or a fatal outcome. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1331–1341. doi: 10.1086/428854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uusitalo-Seppälä R, Huttunen R, Tarkka M, et al. Soluble urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor in patients with suspected infection in the emergency room: a prospective cohort study. J Intern Med. 2012;272:247–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2012.02569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eugen-Olsen J, Andersen O, Linneberg A, et al. Circulating soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor predicts cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes and mortality in the general population. J Intern Med. 2010;268:296–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2010.02252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wei C, Trachtman H, Li J, et al. Circulating suPAR in two cohorts of primary FSGS. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:2051–2059. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012030302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wei C, El Hindi S, Li J, et al. Circulating urokinase receptor as a cause of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nat Med. 2011;17:952–960. doi: 10.1038/nm.2411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sier CF, Sidenius N, Mariani A, et al. Presence of urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor in urine of cancer patients and its possible clinical relevance. Lab Invest. 1999;79:717–722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mustjoki S, Sidenius N, Sier CF, Blasi F, Elonen E, Alitalo R, Vaheri A. Soluble urokinase receptor levels correlate with number of circulating tumor cells in acute myeloid leukemia and decrease rapidly during chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 2000;60:7126–7132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rabna P, Andersen A, Wejse C, et al. Urine suPAR levels compared with plasma suPAR levels as predictors of post-consultation mortality risk among individuals assumed to be TB-negative: a prospective cohort study. Inflammation. 2010;33:374–380. doi: 10.1007/s10753-010-9195-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sorio C, Mafficini A, Furlan F, et al. Elevated urinary levels of urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma identify a clinically high-risk group. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:448. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Outinen TK, Tervo L, Mäkelä S, et al. Plasma levels of soluble urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor associate with the clinical severity of acute Puumala hantavirus infection. PLoS One. 2013;8:e71335. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vapalahti O, Lundkvist Å, Kallio-Kokko H, Paukku K, Julkunen I, Lankinen H, Vaheri A. Antigenic properties and diagnostic potential of Puumala virus nucleocapsid protein expressed in insect cells. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:119–125. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.1.119-125.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Outinen TK, Mäkelä SM, Ala-Houhala IO, et al. High activity of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase is associated with renal insufficiency in Puumala hantavirus induced nephropathia epidemica. J Med Virol. 2011;83:731–737. doi: 10.1002/jmv.22018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Libraty DH, Mäkelä S, Vlk J, Hurme M, Vaheri A, Ennis FA, Mustonen J. The degree of leukocytosis and urine GATA-3 mRNA levels are risk factors for severe acute kidney injury in Puumala virus nephropathia epidemica. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35402. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schrocksnadel K, Wirleitner B, Winkler C, Fuchs D. Monitoring tryptophan metabolism in chronic immune activation. Clin Chim Acta. 2006;364:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2005.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Laich A, Neurauter G, Widner B, Fuchs D. More rapid method for simultaneous measurement of tryptophan and kynurenine by HPLC. Clin Chem. 2002;48:579–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McQuarrie EP, Shakerdi L, Jardine AG, Fox JG, Mackinnon B. Fractional excretions of albumin and IgG are the best predictors of progression in primary glomerulonephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:1563–1569. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mäkelä S, Mustonen J, Ala-Houhala I, Hurme M, Koivisto AM, Vaheri A, Pasternack A. Urinary excretion of interleukin-6 correlates with proteinuria in acute Puumala hantavirus-induced nephritis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43:809–816. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2003.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ecke TH, Schlechte HH, Schulze G, Lenk SV, Loening SA. Four tumour markers for urinary bladder cancer--tissue polypeptide antigen (TPA), HER-2/neu (ERB B2), urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) and TP53 mutation. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:635–641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Soydinc HO, Duranyildiz D, Guney N, Derin D, Yasasever V. Utility of serum and urine uPAR levels for diagnosis of breast cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:2887–2889. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.6.2887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sier CF, Nicoletti I, Santovito ML, et al. Metabolism of tumour-derived urokinase receptor and receptor fragments in cancer patients and xenografted mice. Thromb Haemost. 2004;91:403–411. doi: 10.1160/TH03-06-0351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Andersen O, Eugen-Olsen J, Kofoed K, Iversen J, Haugaard SB. Soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor is a marker of dysmetabolism in HIV-infected patients receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Med Virol. 2008;80:209–216. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sidenius N, Sier CF, Blasi F. Shedding and cleavage of the urokinase receptor (uPAR): identification and characterisation of uPAR fragments in vitro and in vivo. FEBS Lett. 2000;475:52–56. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01624-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wagner SN, Atkinson MJ, Wagner C, Hofler H, Schmitt M, Wilhelm O. Sites of urokinase-type plasminogen activator expression and distribution of its receptor in the normal human kidney. Histochem Cell Biol. 1996;105:53–60. doi: 10.1007/BF01450878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jefferson JA, Alpers CE. Glomerular disease: 'suPAR'-exciting times for FSGS. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2013;9:127–128. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2013.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shankland SJ, Pollak MR. A suPAR circulating factor causes kidney disease. Nat Med. 2011;17:926–927. doi: 10.1038/nm.2443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Franco Palacios CR, Lieske JC, Wadei HM, et al. Urine but not serum soluble urokinase receptor (suPAR) may identify cases of recurrent FSGS in kidney transplant candidates. Transplantation. 2013;96:394–399. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3182977ab1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Krautkramer E, Grouls S, Stein N, Reiser J, Zeier M. Pathogenic old world hantaviruses infect renal glomerular and tubular cells and induce disassembling of cell-to-cell contacts. J Virol. 2011;85:9811–9823. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00568-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li XD, Kukkonen S, Vapalahti O, Plyusnin A, Lankinen H, Vaheri A. Tula hantavirus infection of Vero E6 cells induces apoptosis involving caspase 8 activation. J Gen Virol. 2004;85:3261–3268. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80243-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Markotic A, Hensley L, Geisbert T, Spik K, Schmaljohn C. Hantaviruses induce cytopathic effects and apoptosis in continuous human embryonic kidney cells. J Gen Virol. 2003;84:2197–2202. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19090-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Collan Y, Mihatsch MJ, Lähdevirta J, Jokinen EJ, Romppanen T, Jantunen E. Nephropathia epidemica: mild variant of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome. Kidney Int Suppl. 1991;35:S62–S71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Collan Y, Lähdevirta J, Jokinen EJ. Electron Microscopy of Nephropathia Epidemica. Glomerular changes. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histol. 1978;377:129–144. doi: 10.1007/BF00427001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]