Abstract

Objective

To estimate long term trends in estrogen–progestin prevalence for the U.S. female population by year and age.

Methods

We integrated data on oral estrogen–progestin use from NHANES 1999–2010 with data from the National Prescription Audit 1970–2003. Distributions of estrogen–progestin by age from NHANES were applied to the prescription data, and calibration and interpolation procedures were used to generate estrogen–progestin prevalence estimates by single year of age and single calendar year for 1970–2010.

Results

Estimated prevalence of oral estrogen–progestin was below 0.5% in the 1970s, began to rise in the early 1980s, and almost tripled between 1990 and the late 1990s. The age-adjusted prevalence for women aged 45–64 peaked at 13.5% in 1999, with highest use among 57 year-old women (23.2%). Prevalence of estrogen–progestin use declined dramatically in the early 2000s, with only 2.7% of women aged 45–64 using estrogen–progestin in 2010, which is comparable to prevalence levels in the mid-1980s.

Conclusion

The dramatic rise and fall of estrogen–progestin use over the past 40 years provides an illuminating case study of prescription practices before, during, and after the development of evidence regarding benefits and harms.

INTRODUCTION

Use of postmenopausal hormones has varied over the past decades. Until the 1970s, estrogen formulations were most common (1, 2). In 1975, an elevated risk of endometrial cancer from estrogen therapy was recognized (3–5), and postmenopausal hormone use declined (6–8). Thereafter, studies demonstrated that adding progestin to estrogen reduced endometrial cancer risk (9, 10), and suggested additional benefits (11, 12). The number of estrogen–progestin prescriptions grew rapidly until the early 2000s (13, 14). In 2002, the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) clinical trial found that estrogen–progestin use among healthy postmenopausal women was associated with elevated risk of breast cancer, coronary heart disease, stroke, and venous thromboembolic disease (12). Estrogen-progestin use decreased dramatically (14–18), and in January 2003, the FDA recommended that manufacturers label estrogen–progestin products with information on possible health risks (19).

Recent ecological studies showed that breast cancer incidence declined between 2001 and 2004, simultaneously with the decline of estrogen–progestin use (20–23), igniting a discussion of whether and to what extent changes in estrogen–progestin use contributed to changes in breast cancer incidence (24–30).

Long term nationally representative data on estrogen–progestin use are needed to investigate the historical impacts of estrogen–progestin use on population-level trends in health outcomes related to its use. Estrogen-progestin prevalence estimates are available from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) since 1999 (31). Available earlier national prescription sales counts (32–35) are only an indirect measure of prevalence (6, 8, 13). We sought to estimate nationally representative trends in estrogen–progestin prevalence for the US female population by calendar year and age by integrating recent NHANES prevalence estimates with prescription drug statistics dating back to 1970.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

For our analysis, we used publications based on the National Prescription Audit 1970–2003 and NHANES 1999–2010 (6, 8, 13, 14, 36). The NHANES data are publically available and were validated by the CDC. The National Prescription Audit is validated by the IMS Institute. From the NHANES data, we calculated odds ratios of estrogen–progestin use between age groups. Using these odds ratios, we split the aggregated prescription data into age specific data. Finally, we combined the two data sources and interpolated estrogen–progestin prevalence estimates by single year of age and single calendar year. This study was determined to be exempt from human subjects review by the University of Wisconsin Health Sciences Institutional Review Board under category 4 since the data are publicly available.

We used data from six NHANES survey waves on the percentage of women aged 40 and older reporting current use of oral estrogen–progestin between 1999 and 2010 (36). NHANES is a program designed to assess the health of the U.S. population, and has been conducted annually and published biannually since 1999, with less regular prior waves. It uses a multistage probability sampling design to select a population sample that is representative of the civilian non-institutionalized US population (37). A more detailed description of the NHANES reproductive health module is given in Sprague et al. (31). Sample sizes of women aged 40 and older with estrogen–progestin data during the NHANES waves in 1999, 2001, 2003, 2005, 2007, and 2009 were 1329, 1433, 1420, 1276, 1763, 1739, respectively. We calculated the prevalence of current use of oral estrogen–progestin by age (five-year age groups), in two calendar-year increments corresponding to the NHANES survey waves. The data was analyzed in the R survey package, and weighted by the provided sampling weights to account for sampling design in order to calculate nationally representative estimates.

We relied on publications which reported national counts of postmenopausal hormone prescriptions based on data from the National Prescription Audit to assess the use of estrogen–progestin prior to 1999. The National Prescription Audit is an industry standard source of national prescription activity for all pharmaceutical products (38). Data are collected from a representative sample of retail, standard mail service, specialty mail service, and long term care facilities. Several papers were identified which reported counts of non-contraceptive estrogens and/or progestins, covering the time period 1970–2003 (6, 8, 13, 14). Each study sought to include all non-contraceptive estrogen and progestin preparations used at the time. A more complete description of the specific products included in each study is available in the source publications.

Since information on the number of prescription of both estrogen and progestin used together was not directly available from the National Prescription Audit publications, counts of prescriptions for estrogen–progestin were estimated by multiplying the total number of non-contraceptive postmenopausal estrogen prescriptions by the reported fraction of estrogen prescriptions that were prescribed along with progestin. For years in which no published estrogen prescription data was available (1993–1994), linear interpolation was performed. Similarly, in years in which no estimate of the fraction of co-prescribed progestin was available (1970–1973, 1987–1991, 1993–2000), linear interpolation of that fraction was performed. The estrogen–progestin prescription counts were normalized to annual population denominator counts of US women aged 40 and older, as obtained from the US Census (39).

We used a weighted logistic regression model to measure the association between estrogen–progestin use and age in the NHANES 1999–2010 data, while adjusting for NHANES survey wave as a measure of calendar year. We tested an interaction term between age group and survey year, which was not statistically significant (P-value 0.35), and subsequently excluded the interaction term from the model. In addition to the odds ratios, we calculated biannual probabilities of estrogen–progestin use by age group.

The estrogen–progestin use odds ratios by age were numerically applied to the normalized prescription counts between 1970 and 2003, such that the variation in estrogen–progestin use by age observed in NHANES 1999–2010 was mirrored in the prescription drug data, resulting in estimated age-specific prescription rates of estrogen–progestin use between 1970 and 2003 by five-year age group. These prescription rates were then calibrated to the NHANES data in order to produce pre-1999 estimates of estrogen–progestin prevalence.

To generate single calendar year and single year of age prevalence estimates, we implemented a two-step interpolation process. First, the NHANES biannual prevalence estimates between 1999 and 2010 from the logistic regression were interpolated to annual probabilities per five-year age group, with one year knot per NHANES survey. The annual NHANES data and the calibrated prescriptions were then combined into one dataset in the cut-off year 2003. These prevalence estimates by five-year age groups that covered the entire period (1970–2010) were then interpolated to single year age groups, with one age knot per five-year-age group.

RESULTS

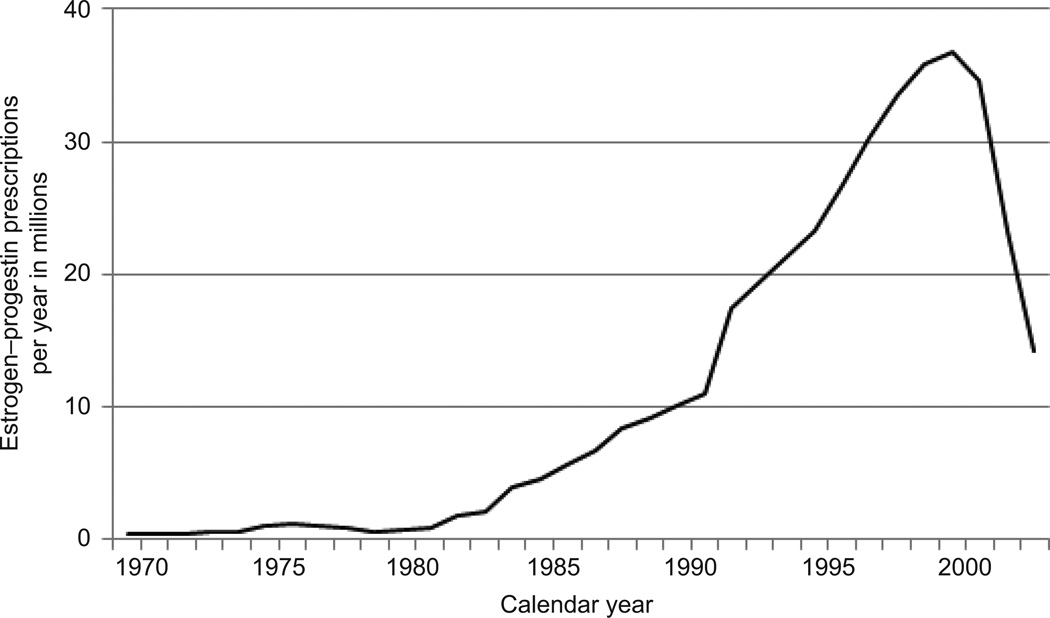

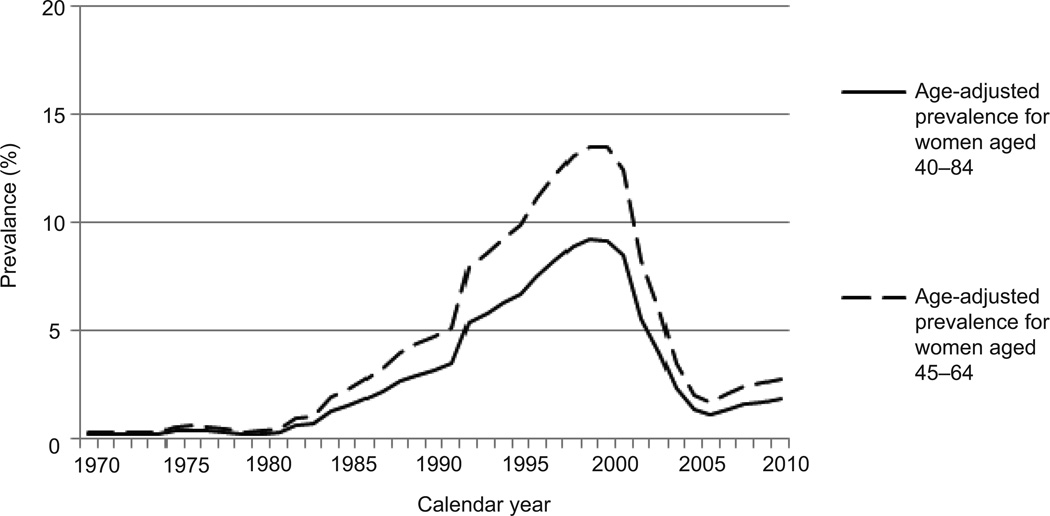

Estrogen-progestin prescriptions varied substantially over time (Figure 1). The estimated age-adjusted prevalence of oral estrogen–progestin use was below 1% for all age groups until about 1980, began to rise in the early 1980s and grew by approximately 200% between 1990 and 1999. The absolute increase in estrogen–progestin prevalence for women aged 45–64 years old was 4.4% between 1980 and 1990, and 8.8% between 1990 and 2000 (Table 1). Age-adjusted estrogen–progestin prevalence in women aged 45–64 peaked at 13.5% in 1999. Increases in use were statistically significant (P<0.001) based on linear trends reported in Wysowski et al (13). Estrogen-progestin prevalence declined by about 85% between 2001 and 2005. The relative change per year during 2000–2010 was associated with an odds ratio of 0.174 (95% confidence interval 0.087, 0.346; P<0.001). Annual change was not significantly different across age groups (P=0.35). The prevalence in 2010 was similar to that observed in the mid-1980s (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Postmenopausal estrogen–progestin prescriptions in the United States, 1970–2003.

Table 1.

Estimated prevalence of oral postmenopausal estrogen–progestin use in the United States by age and calendar year, 1970–2010

| 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 2010 | Absolute change 1980 – 1990 |

Absolute change 1990 – 2000 |

Absolute change* 2000 – 2010 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| 40 | <0.1% | <0.1% | 0.2% | 0.6% | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.4% | −0.5% |

| 45 | 0.0% | 0.1% | 1.0% | 3.2% | 0.6% | 0.9% | 2.2% | −2.6% |

| 50 | 0.2% | 0.3% | 4.2% | 12.4% | 2.4% | 3.9% | 8.2% | −10.0% |

| 55 | 0.4% | 0.6% | 7.9% | 21.5% | 4.6% | 7.3% | 13.6% | −16.9% |

| 60 | 0.2% | 0.4% | 5.0% | 14.5% | 2.9% | 4.6% | 9.5% | −11.7% |

| 65 | 0.2% | 0.2% | 3.4% | 10.3% | 1.9% | 3.2% | 6.9% | −8.4% |

| 70 | 0.1% | 0.2% | 2.9% | 8.7% | 1.6% | 2.7% | 5.9% | −7.1% |

| 75 | 0.1% | 0.1% | 1.2% | 3.8% | 0.7% | 1.1% | 2.6% | −3.1% |

| 80 | <0.1% | 0.1% | 0.9% | 2.9% | 0.5% | 0.8% | 2.0% | −2.4% |

| 45–64† | 0.2% | 0.3% | 4.7% | 13.5% | 2.7% | 4.4% | 8.8% | −10.8% |

| 40–84‡ | 0.2% | 0.2% | 3.2% | 9.2% | 1.8% | 2.9% | 6.0% | −7.4% |

Relative change per year during 2000–2010 was associated with odds ratio 0.174, 95% confidence interval 0.087, 0.346; P<0.001. Annual change was not significantly different across age groups (P=0.35).

Age-adjusted to the US 2000 (45–64 year-old) standard population

Age-adjusted to the US 2000 (40–84 year-old) standard population

Figure 2.

Estimated age-adjusted prevalence of oral estrogen–progestin use 1970–2010 among women aged 45–64 years (dashed line) and aged 40–84 years (solid line).

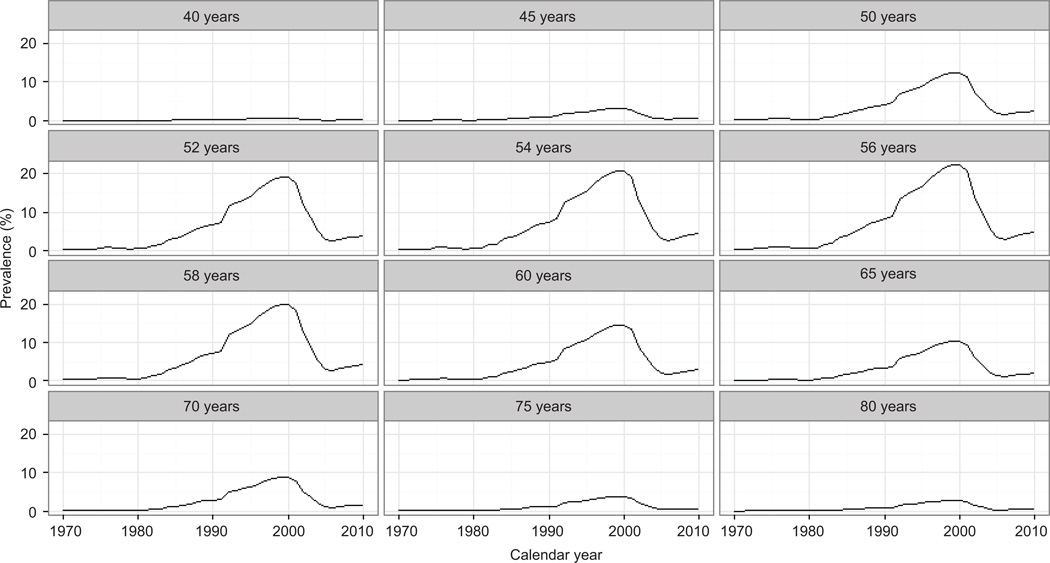

Estrogen–progestin use varied substantially by age. Estrogen–progestin prevalence was less than 5% across all years among women aged 45 years and younger, as well as among women aged 75 years and older. Peak use was observed among women in their late 50s (Figure 3). Maximum usage estimates were reached in 1999, with an estimated 23.2% prevalence among 57-year-old women (12.4% among 50-year-old, 14.6% among 60-year-old, and 10.4% among 65-year-old women). Between 2002 and 2006, estrogen–progestin use decreased steeply in all age groups. Absolute changes during that time varied according to the different levels of estrogen–progestin prevalence per age group (Table 1), but the relative annual decline was similar in all groups, and ranged from about −43% in 2004 and 2005 to about −16% in 2006. Post-2000 usage was lowest in the mid-2000s, with the lowest prevalence for women aged 45–64 observed in 2006 at 1.7%. There is some suggestion of a very modest increase that occurred in the late 2000s (Figures 2–3).

Figure 3.

Estimated prevalence of oral estrogen–progestin use by age, 1970–2010.

DISCUSSION

Our analyses provide age- and year-specific estimates for estrogen–progestin use during 1970–2010 representative of the US female population. Our estimates of estrogen–progestin usage between 1970 and 2010 are unique in the level of detail they provide, and could help generate new hypotheses for future research around past and current health outcomes associated with estrogen–progestin use. The population-level impact of estrogen–progestin use on women’s health has likely varied according to the changes in estrogen–progestin prevalence in the past decades.

Our estimates are consistent with patterns shown in previous publications amongst specific study populations during more restricted time periods (15, 17, 32–35, 40–43). Our modeled estrogen–progestin prevalence trends are nationally representative and more comprehensive by providing estimates per calendar year and single year of age rather than aggregate estimates over time and age groups. In some cases, our estimates are slightly lower compared with previous publications, particularly when comparing them with studies conducted on enrollees of health maintenance organizations (HMOs). For example, Buist et al (15) reported a 14.6% estrogen–progestin prevalence among women aged 40–80 in 1999 whereas the corresponding value in our study was 9.5%. This most likely reflects the elevated use of postmenopausal hormones among women enrolled in HMOs relative to use among the general population which also includes uninsured women. There is little nationally representative estrogen–progestin data in the published literature with which to compare our results more directly, and we found none that covered comparably long time periods. In a study based on NHANES data, Brett et al (43) reported estrogen–progestin prevalence estimates in 1999 quite comparable to ours.

Our study has limitations. First, NHANES data on postmenopausal estrogen–progestin use relies on self-reports. However, prior studies indicate good reliability and validity for self-reported hormone use (44–46). Secondly, we relied on prescription dispensary data from several publications. While these data may not precisely reflect actual use since some dispensed prescriptions may not be used, they arise from a broadly representative sample of prescription dispensaries across the US. In order to account for unused prescriptions, we calibrated the prescription information to the NHANES data. We did not have prescription drug data by age, and therefore applied odds ratios between age groups from the NHANES 1999–2010 data to the prescription data. This assumes that odds ratios of estrogen–progestin use between age groups were stable over time. We did not find evidence contradicting this, and the test for effect modification between age and time in the NHANES data was not statistically significant. We interpolated estrogen use in 1993/1994, and the fraction of progestin among estrogen users in years in which no estimate of that fraction was available. Notably, the fraction of progestin among estrogen users reported by other authors appears to have been relatively stable during these time periods (6, 8, 13, 14). Nevertheless, our estimates only approximate true estrogen–progestin usage if our assumption of stable odds ratios holds true, and if the fraction of progestin among estrogen users did not fluctuate much in the 1990s. We only modeled estrogen–progestin estimates for age groups 40–84, but prevalence in women aged <40 and ≥85 is very low (36). Finally, our results reflect oral estrogen–progestin use, because detailed data on use of patches, creams, suppositories, and injections were not available from NHANES throughout the duration of the study period. Notably, we previously reported that 90% of women reporting use of postmenopausal hormones in NHANES during 1999–2010 used oral preparations (31).

Our results show the evolution of estrogen–progestin use during a 40 year period in which the evidence base for benefits and harms grew from nearly no evidence, to a steadily increasing number of observational studies, and finally to randomized trial data (12, 47–51). While demonstrating the capacity for the clinical community to rapidly respond to new evidence, these trends also illustrate susceptibility towards elevated prescription use in the absence of definitive evidence. Future studies evaluating the use of low-dose, short duration, and other alternative postmenopausal hormone preparations will be needed to study the next chapter of hormone therapy in the US.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH grants U01CA152958 and P30CA014520.

The authors thank Dr. Jeanne Mandelblatt and Aimee Near for their review and suggestions for this manuscript, John Hampton for assistance with data collection and analysis, and Julie McGregor for project coordination.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wallach S, Henneman PH. Prolonged estrogen therapy in postmenopausal women. JAMA. 1959;171:1637–1642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Markush RE, Turner SL. Epidemiology of exogenous estrogens. HSMHA Health Rep. 1971;86:74–86. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith DC, Prentice R, Thompson DJ, Herrmann WL. Association of Exogenous Estrogen and Endometrial Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1975;293:1164–1167. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197512042932302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ziel HK, Finkle WD. Increased Risk of Endometrial Carcinoma among Users of Conjugated Estrogens. N Engl J Med. 1975;293:1167–1170. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197512042932303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiss NS, Szekely DR, English DR, Schweid AI. Endometrial cancer in relation to patterns of menopausal estrogen use. JAMA. 1979;242:261–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kennedy DL, Baum C, Forbes MB. Noncontraceptive estrogens and progestins: use patterns over time. Obstet Gynecol. 1985;65:441–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Standeven M, Criqui M, Klauber MR, Gabriel S, Barrett-Connor E. Correlates of change in postmenopausal estrogen use in a population-based study. Am J Epidemiol. 1986;124:268–274. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hemminki E, Kennedy DL, Baum C, McKinlay SM. Prescribing of noncontraceptive estrogens and progestins in the United States, 1974–86. Am J Public Health. 1988;78:1479–1481. doi: 10.2105/ajph.78.11.1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thom M, White P, Williams RM, Sturdee DW, Paterson MEL, Wade-Evans T, et al. Prevention and treatment of endometrial disease in climacteric women receiving oestrogen therapy. Lancet. 1979;314:455–457. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)91504-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paterson ME, Wade-Evans T, Sturdee DW, Thom MH, Studd JW. Endometrial disease after treatment with oestrogens and progestogens in the climacteric. Br Med J. 1980;280:822–824. doi: 10.1136/bmj.280.6217.822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hammond CB, Jelovsek FR, Lee KL, Creasman WT, Parker RT. Effects of long-term estrogen replacement therapy. I. Metabolic effects. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1979;133:525–536. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(79)90288-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, LaCroix AZ, Kooperberg C, Stefanick ML, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wysowski DK, Golden L, Burke L. Use of menopausal estrogens and medroxyprogesterone in the United States, 1982–1992. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85:6–10. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(94)00339-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hersh AL, Stefanick ML, Stafford RS. National use of postmenopausal hormone therapy: annual trends and response to recent evidence. JAMA. 2004;291:47–53. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buist DS, Newton KM, Miglioretti DL, Beverly K, Connelly MT, Andrade S, et al. Hormone therapy prescribing patterns in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:1042–1050. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000143826.38439.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelly JP, Kaufman DW, Rosenberg L, Kelley K, Cooper SG, Mitchell AA. Use of postmenopausal hormone therapy since the Women's Health Initiative findings. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2005;14:837–842. doi: 10.1002/pds.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hing E, Brett KM. Changes in U.S. prescribing patterns of menopausal hormone therapy, 2001–2003. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:33–40. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000220502.77153.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wysowski DK, Governale LA. Use of menopausal hormones in the United States, 1992 through June, 2003. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2005;14:171–176. doi: 10.1002/pds.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. [Retrieved June 15 2014];Estrogen and Estrogen with Progestin Therapies for Postmenopausal Women. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/InformationbyDrugClass/ucm135318.htm.

- 20.Ravdin PM, Cronin KA, Howlader N, Berg CD, Chlebowski RT, Feuer EJ, et al. The decrease in breast-cancer incidence in 2003 in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1670–1674. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr070105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kerlikowske K, Miglioretti DL, Buist DS, Walker R, Carney PA. Declines in invasive breast cancer and use of postmenopausal hormone therapy in a screening mammography population. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1335–1339. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robbins AS, Clarke CA. Regional changes in hormone therapy use and breast cancer incidence in California from 2001 to 2004. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3437–3439. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.4132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clarke CA, Glaser SL, Uratsu CS, Selby JV, Kushi LH, Herrinton LJ. Recent declines in hormone therapy utilization and breast cancer incidence: clinical and population-based evidence. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:e49–e50. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.6504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zahl PH, Maehlen J. A decline in breast-cancer incidence. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:510–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McNeil C. Breast cancer decline mirrors fall in hormone use, spurs both debate and research. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:266–267. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robbins AS, Clarke CA. Re: Declines in invasive breast cancer and use of postmenopausal hormone therapy in a screening mammography population. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1815. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clarke CA, Glaser SL. Declines in breast cancer after the WHI: apparent impact of hormone therapy. CCC. 2007;18:847–852. doi: 10.1007/s10552-007-9029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glass AG, Lacey JV, Jr, Carreon JD, Hoover RN. Breast cancer incidence, 1980–2006: combined roles of menopausal hormone therapy, screening mammography, and estrogen receptor status. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1152–1161. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jemal A, Ward E, Thun MJ. Recent trends in breast cancer incidence rates by age and tumor characteristics among U.S. women. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9:R28. doi: 10.1186/bcr1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li CI, Daling JR. Changes in breast cancer incidence rates in the United States by histologic subtype and race/ethnicity, 1995 to 2004. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:2773–2780. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sprague BL, Trentham-Dietz A, Cronin KA. A Sustained Decline in Postmenopausal Hormone Use: Results From the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2010. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:595–603. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318265df42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whitlock EP, Johnson RE, Vogt TM. Recent patterns of hormone replacement therapy use in a large managed care organization. J Womens Health. 1998;7:1017–1026. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1998.7.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harris RB, Laws A, Reddy VM, King A, Haskell WL. Are women using postmenopausal estrogens? A community survey. Am J Public Health. 1990;80:1266–1268. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.10.1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barrett-Connor E, Wingard DL, Criqui MH. Postmenopausal estrogen use and heart disease risk factors in the 1980s. Rancho Bernardo, Calif, revisited. JAMA. 1989;261:2095–2100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Colditz GA, Hankinson SE, Hunter DJ, Willett WC, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, et al. The use of estrogens and progestins and the risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1589–1593. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199506153322401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) [Retrieved June 15, 2014];National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/NHANES.htm.

- 37.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [Retrieved June 15, 2014];National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: Plan and Operations, 1999–2010. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_01/sr01_056.pdf.

- 38.IMS Health Institute for Healthcare Informatics. [Retrieved June 15, 2014];HSRN Data Brief: National Prescription Audit. Available at: http://www.imshealth.com/deployedfiles/ims/Global/Content/Insights/Researchers/NPA_Data_Brief.pdf.

- 39.United States Census. [Retrieved June 15, 2014];Population Estimates Historical Data. Available at: http://www.census.gov/popest/data/historical/index.html.

- 40.Haas JS, Kaplan CP, Gerstenberger EP, Kerlikowske K. Changes in the use of postmenopausal hormone therapy after the publication of clinical trial results. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:184–188. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-3-200402030-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim JK, Alley D, Hu P, Karlamangla A, Seeman T, Crimmins EM. Changes in postmenopausal hormone therapy use since 1988. Womens Health Issues. 2007;17:338–341. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Egeland GM, Matthews KA, Kuller LH, Kelsey SF. Characteristics of noncontraceptive hormone users. Prev Med. 1988;17:403–411. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(88)90039-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brett KM, Reuben CA. Prevalence of estrogen or estrogen-progestin hormone therapy use. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:1240–1249. doi: 10.1016/j.obstetgynecol.2003.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Merlo J, Berglund G, Wirfalt E, Gullberg B, Hedblad B, Manjer J, et al. Self-administered questionnaire compared with a personal diary for assessment of current use of hormone therapy: an analysis of 16,060 women. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:788–792. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.8.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Banks E, Beral V, Cameron R, Hogg A, Langley N, Barnes I, et al. Agreement between general practice prescription data and self-reported use of hormone replacement therapy and treatment for various illnesses. J Epidemiol Biostat. 2001;6:357–363. doi: 10.1080/13595220152601837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sandini L, Pentti K, Tuppurainen M, Kroger H, Honkanen R. Agreement of self-reported estrogen use with prescription data: an analysis of women from the Kuopio Osteoporosis Risk Factor and Prevention Study. Menopause. 2008;15:282–289. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181334b6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weiss NS, Ure CL, Ballard JH, Williams AR, Daling JR. Decreased risk of fractures of the hip and lower forearm with postmenopausal use of estrogen. N Engl J Med. 1980;303:1195–1198. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198011203032102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA. Estrogen replacement therapy and coronary heart disease: a quantitative assessment of the epidemiologic evidence. Prev Med. 1991;20:47–63. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(91)90006-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grady D, Rubin SM, Petitti DB, Fox CS, Black D, Ettinger B, et al. Hormone therapy to prevent disease and prolong life in postmenopausal women. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:1016–1037. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-117-12-1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Newcomb PA, Storer BE. Postmenopausal hormone use and risk of large-bowel cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:1067–1071. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.14.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hulley S, Grady D, Bush T, Furberg C, Herrington D, Riggs B, et al. Randomized trial of estrogen plus progestin for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in postmenopausal women. Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study (HERS) Research Group. JAMA. 1998;280:605–613. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.7.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]