Abstract

Objective

To examine the association between body mass index (BMI [calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared]) and timing of pubertal onset in a population-based sample of US boys.

Design

Longitudinal prospective study.

Setting

Ten US sites that participated in the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development.

Participants

Of 705 boys initially enrolled in the study, information about height and weight measures and pubertal stage by age 11.5 years was available for 401 boys.

Main Exposure

The BMI trajectory created from measured heights and weights at ages 2, 3, 4.5, 7, 9, 9.5, 10.5, and 11.5 years.

Main Outcome Measure

Onset of puberty at age 11.5 years as measured by Tanner genitalia staging.

Results

Boys in the highest BMI trajectory (mean BMI z score at age 11.5 years, 1.84) had a greater relative risk of being prepubertal compared with boys in the lowest BMI trajectory (mean BMI z score at age 11.5 years, −0.76) (adjusted relative risk=2.63; 95% confidence interval, 1.05–6.61; P=.04).

Conclusions

The relationship between body fat and timing of pubertal onset is not the same in boys as it is in girls. Further studies are needed to better understand the physiological link between body fat and timing of pubertal onset in both sexes.

Understanding the association between fat mass and pubertal timing is important given the current epidemic of obesity among US children. Obesity rates among US girls and boys have nearly tripled since the 1960s,1 prompting concern about the effect of this excess weight on the timing of pubertal development.

Despite a relatively extensive literature demonstrating an inverse association between body fat and age at pubertal onset in girls,2–5 similar studies in boys have been lacking. One recent cross-sectional study showed the opposite relationship between body fat and sexual maturation among boys; boys with a higher body mass index (BMI [calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared]) were more likely to have later rather than earlier sexual maturation.6 If differences in body fat were to precede differences in the timing of appearance of secondary sexual characteristics, this would provide evidence for a possible causal link between greater body fat mass and later onset of puberty in boys. Longitudinal studies are therefore needed to better understand sex-based differences in the relationship between body fat and pubertal timing as well as possible implications of increasing BMI among US boys. We report the findings of a population-based longitudinal study that tested the hypothesis that a higher BMI z score trajectory from ages 2 to 11.5 years would be associated with remaining prepubertal at age 11.5 years among a socioeconomically diverse sample of US boys.

METHODS

SAMPLE

The cohort consisted of boys enrolled in the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development, a study of child behavior, growth, and development that recruited full-term singleton children born in 1991 in 10 geographic areas.7 Approval was obtained by the pertinent institutional review boards. Of 1364 initial study participants, of which 705 were boys, 1077 remained in the study at age 11.5 years.

MAIN EXPOSURE

Height and weight were measured during study visits at ages 2, 3, 4.5, 7, 9, 9.5, 10.5, and 11.5 years, and the BMI z score for each age was calculated.8 Boys were classified into 1 of 3 BMI trajectories generated from these data as described later. The BMI trajectory group served as the primary predictor.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURE

Similar to other previous studies of puberty in boys,6,9 we elected to categorize pubertal initiation based on Tanner genitalia staging. Pubarche was not assessed as it is independent of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. Tanner genitalia staging was performed at ages 9.5, 10.5, and 11.5 years by visual inspection. Examiners were pediatric endocrinologists or trained nurse practitioners who were certified in Tanner staging via the same methods used for other large population-based studies of puberty10 and were recertified every 6 months. The Tanner genitalia stage was rated separately from pubic hair development using Tanner’s original criteria.11 Boys with Tanner stage 1 genitalia at age 11.5 years were defined as prepubertal; the remainder of the cohort was classified as pubertal. We selected age 11.5 years as the age at which to evaluate the outcome based on an evaluation of the proportion of boys remaining prepubertal at the different assessment ages. At age 11.5 years, 49 (12.2%) of the boys were prepubertal, which we felt represented both a clinically significant tail of the distribution and a substantial enough sample size to allow meaningful statistical analysis.

Because pubertal development does not regress, if Tanner stage data were missing at age 11.5 years but a boy had Tanner stage 2 development by ages 9.5 and 10.5 years, the participant was classified as pubertal (n=43). Boys with Tanner stage 2 genitalia at age 9.5 or 10.5 years but noted to have Tanner stage 1 genitalia at age 11.5 years were considered to have implausible data and were excluded from the analysis (n=14).

COVARIATES

The income-to-needs (ITN) ratio at 2 years, a measure of socioeconomic status that represents total family income relative to the federal poverty line for a family of a particular size, and race (white vs nonwhite) were included as covariates, as higher social class and black race are associated with earlier maturation in boys.6,12

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Data analysis was performed using SAS version 9.1 statistical software (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, North Carolina). We used χ2 analysis and analysis of variance to describe the sample. To assess the relationship between growth patterns and onset of puberty, we performed growth curve or trajectory analysis, which identified BMI trajectories from the population data, generated growth data for individuals, and then classified individuals into 1 of the BMI trajectories. This allowed us to incorporate all available BMI data.13

Owing to the limited number of boys with the primary outcome of later onset of puberty, we elected to use a 3-group trajectory model. We performed imputation with SAS version 9.1 statistical software using the ITN ratio at 2 years and all available BMI measurements. We then defined BMI z score trajectories controlling for the ITN ratio. We assessed the relative risk of being prepubertal according to trajectory membership, adjusting for race and ITN ratio. Finally, unadjusted percentages of later onset of puberty by trajectory group were calculated.

Attrition analyses comparing the sample of boys with complete data for BMI trajectory and puberty assessed at age 11.5 years revealed no significant differences between children included in this analysis (N=401) and children without complete data and not included (n=304) for race (P=.22). However, boys in the sample had a lower ITN ratio compared with boys excluded (mean [SD], 3.31 [2.80] vs 3.94 [3.65], respectively; P=.03) as well as a lower BMI z score at age 11.5 years (mean [SD], 0.54 [1.14] vs 0.81 [1.10], respectively; P=.05). No child in this cohort had any chronic medical condition or medication use that would have had a substantial effect on weight, puberty, or the association between the two.

RESULTS

For the sample of 401 boys with BMI data contributing to the trajectory analysis and data on Tanner genitalia stage at age 11.5 years, 82 (20.5%) were nonwhite and 56 (14.8%) had an ITN ratio less than 1 (indicating that they were living in poverty). Rates of overweight (BMI ≥85th and <95th percentiles) and obesity (BMI ≥95th percentile) at age 11.5 years were 14.4% and 19.4%, respectively. Overall, 49 boys (12.2%) were prepubertal at age 11.5 years by Tanner genitalia staging.

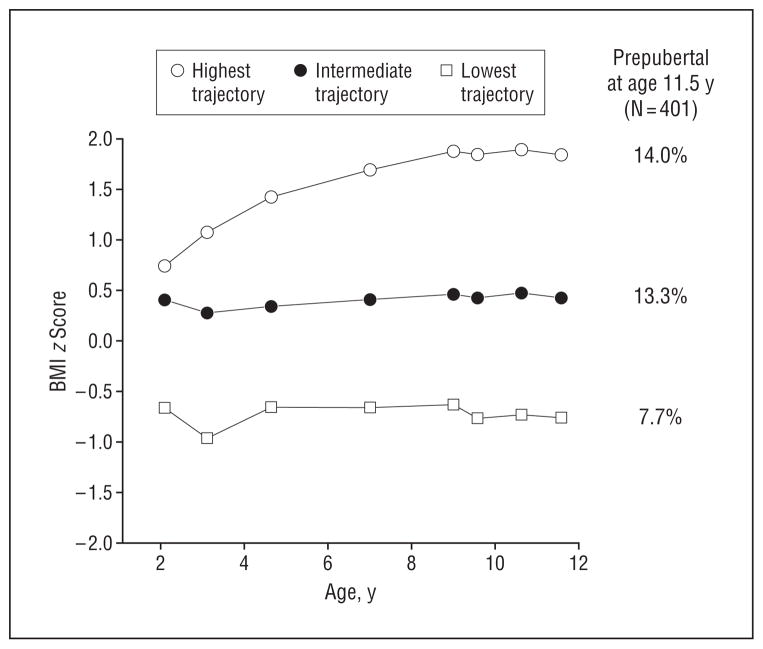

The 3 BMI z score trajectories identified for this cohort of boys are shown in the Figure. The highest BMI z score trajectory had a mean (SD) BMI z score of 1.84 (0.50) at age 11.5 years and included 114 boys (28.4%). The lowest BMI z score trajectory had a mean (SD) BMI z score of −0.76 (0.63) at age 11.5 years and included 91 boys (22.7%). The intermediate BMI z score trajectory had a mean (SD) BMI z score of 0.41 (0.70) at age 11.5 years and included 196 boys (48.9%). Table 1 shows characteristics of the overall sample and each trajectory group.

Figure.

Highest, intermediate, and lowest body mass index (BMI [calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared]) trajectories and percentage of boys who were prepubertal at age 11.5 years.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Sample Overall and by Body Mass Index Trajectory Group

| Characteristic | Total Sample (N=401) | Lowest Trajectory (n=91) | Intermediate Trajectory (n=196) | Highest Trajectory (n=114) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI z score, mean (SD) | |||||

| Age, y | |||||

| 2 | 0.24 (0.93) | −0.67 (0.75) | 0.40 (0.78) | 0.74 (0.79) | <.001a |

| 3 | 0.18 (1.13) | −0.96 (0.72) | 0.26 (0.77) | 1.06 (1.10) | <.001a |

| 4.5 | 0.37 (1.04) | −0.66 (0.82) | 0.34 (0.58) | 1.42 (0.88) | <.001a |

| 7 | 0.50 (1.01) | −0.67 (0.53) | 0.40 (0.51) | 1.68 (0.67) | <.001a |

| 9 | 0.61 (1.02) | −0.63 (0.56) | 0.45 (0.49) | 1.86 (0.48) | <.001a |

| 9.5 | 0.54 (1.09) | −0.76 (0.59) | 0.42 (0.60) | 1.83 (0.48) | <.001a |

| 10.5 | 0.59 (1.11) | −0.73 (0.59) | 0.47 (0.62) | 1.89 (0.47) | <.001a |

| 11.5 | 0.54 (1.14) | −0.76 (0.63) | 0.41 (0.70) | 1.84 (0.50) | <.001a |

| Race, No. (%) | .02 | ||||

| White | 319 (79.6) | 78 (85.7) | 160 (81.6) | 81 (71.1) | |

| Nonwhite | 82 (20.5) | 13 (14.3) | 36 (18.4) | 33 (29.0) | |

| ITN ratio | 3.31 (2.80) | 4.02 (3.27) | 3.35 (2.71) | 2.65 (2.38) | .003b |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); ITN, income-to-needs.

Post hoc Tukey tests show that all 3 trajectories’ means are significantly different from each other.

Post hoc Tukey tests show that the highest trajectory is significantly different from the lowest trajectory.

The Figure shows the unadjusted percentages of boys who were prepubertal at age 11.5 years by trajectory group for each of the measures. We found significant differences in the number of boys who were prepubertal at age 11.5 years by Tanner genitalia staging between the highest and lowest trajectories: 16 boys in the highest trajectory (14.0%) were prepubertal compared with 7 boys in the lowest trajectory (7.7%). Table 2 presents the relative risk of being prepubertal at age 11.5 years by BMI trajectory group, adjusting for race and ITN ratio. The relative risk of being prepubertal was significantly greater in the highest BMI trajectory compared with the lowest BMI trajectory. Nonwhite race and lower ITN were associated with a lower relative risk of being prepubertal at age 11.5 years.

Table 2.

Relative Risks and 95% Confidence Intervals for Being Prepubertal by Age 11.5 Years in 378 Boys

| Covariates | RR (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Highest vs lowest BMI trajectory | 2.63 (1.05–6.61)a |

| Intermediate vs lowest BMI trajectory | 2.19 (0.94–5.14) |

| Nonwhite vs white | 0.30 (0.10–0.94)a |

| ITN ratio at 2 y | 1.10 (1.04–1.16)a |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); CI, confidence interval; ITN, income-to-needs; RR, relative risk.

P <.05.

We reran the analysis including the 14 boys with implausible Tanner staging data assuming that all 14 boys were at Tanner stage 2 at age 11.5 years and then assuming that all 14 boys were at Tanner stage 1 at age 11.5 years. The association between trajectory group (highest trajectory vs lowest trajectory) and relative risk of being prepubertal at age 11.5 years remained essentially unchanged (adjusted relative risk=2.58; 95% confidence interval, 1.03–6.46 for the highest trajectory; and adjusted relative risk=2.25; 95% confidence interval, 1.07–4.73 for the lowest trajectory).

COMMENT

To our knowledge, our study represents one of the first longitudinal population-based studies to report that a higher BMI z score trajectory during early to middle childhood may be associated with later onset of puberty among boys. Although further studies of this association are needed, our findings do provide some evidence that greater body fat mass is not linked to an earlier onset of puberty among boys, contrary to what is seen in girls.2–5,14

Only a few published studies have evaluated the association between excess weight and the timing of appearance of secondary sexual characteristics in boys. In 1972, a case-control study of 20 obese and nonobese adolescents showed findings consistent with our study in that Tanner stage 5 was reached later by obese boys than by nonobese boys.15 However, this study was limited by its small sample size, cross-sectional design, and possible selection bias as participants were recruited from a sample referred for obesity evaluation and treatment. Subsequently, in 1978, Laron et al16 compared pubertal timing among 136 obese boys and 48 nonobese control boys. In contrast, they did not find significant differences in the timing of puberty between the 2 groups, but their population was drawn from a single medical center with limited details of the sampling plan.

In a population-based study, Wang6 classified boys aged 8 to 14 years as early maturers if they reached a Tanner genitalia stage earlier than the median age for that stage within the cohort; otherwise, they were categorized as late maturers. Consistent with our findings, boys with a higher BMI were more likely to be classified as late maturers. However, this study was limited by the cross-sectional nature of its design as well as the definition of early and late maturers, which was based on the age at which boys reached any Tanner genitalia stage (stages 2–5) rather than on just stage 2 development, potentially confounding an earlier progression of puberty with an earlier initiation of puberty.17

Also consistent with our findings, in a population-based cohort of 346 boys, Biro et al18 found that boys who had a greater fat mass as measured by the sum of skin-folds had less advanced sexual maturation by age 12 years and that boys who had a higher BMI and greater adiposity reached any maturation stage at older ages. Similar findings were reported from a Spanish male cohort in which a positive correlation was found between age at onset of puberty and BMI at pubertal onset,19 but both studies were limited by the lack of available BMI measurements during early childhood.

In contrast to these studies, Denzer et al20 reported no delays in the timing of puberty as measured by gonadarche but did note decreased testosterone levels among a cohort of obese boys. This sample, however, included only obese children and was drawn from a cohort of children seeking obesity evaluation and treatment, introducing some potential for bias. Another more recent longitudinal study by Buyken et al21 found that prepubertal body composition was not associated with the timing of the pubertal growth spurt in a population-based sample of German children. However, anthropometric measures were used as a proxy for timing of puberty and the sample size was small (N=108).

Much larger male cohort studies from England22 and Sweden23,24 have suggested that boys with a higher pre-pubertal BMI experience an earlier onset of puberty. However, these studies used age at peak height velocity rather than examination of secondary sexual characteristics as a proxy for the timing of pubertal maturation. Given that boys attain peak height velocity only when they reach Tanner stage 3 puberty, an earlier onset of peak height velocity could represent an earlier progression of puberty rather than an earlier initiation of puberty or could represent simply accelerated growth independent of puberty. For example, studies have shown that obese children will demonstrate accelerated growth throughout childhood independent of the timing of puberty.25

Furthermore, the generalizability of these cohort studies to the US male population is unclear given the geographic location and age of the cohorts, which included men born in England between 1927 and 195622 and Swedish boys who were growing up in the early 1970s.23,24 Both cohorts grew up well before the onset of the worldwide childhood obesity epidemic.

Our findings have important implications for understanding sex differences in physiological mechanisms of puberty. Given that puberty is regulated by the gonadotropin-releasing hormone axis for both girls and boys, it is unclear why we found such different associations between body fat and the timing of pubertal onset for the boys compared with the girls in our cohort.5 Although no specific hormonal trigger has been identified as the responsible agent for activation of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone axis, leptin (a hormone produced by fat cells) has been proposed as the hypothesized permissive factor linking body fat and the initiation of puberty for both boys and girls.26 Cross-sectional studies have shown that both boys and girls experience significant elevation in leptin levels during the prepubertal years and into early puberty.26,27 A longitudinal study of 8 boys by Mantzoros et al9 found that leptin levels reached their peak at the onset of puberty, leading Mantzoros and colleagues to conclude that leptin is an important signal responsible for the onset of puberty in boys. However, it is unclear why boys with a higher BMI and presumably a higher leptin level26 would not experience the earlier onset of puberty that is seen in girls. There are sex differences in leptin levels as children progress through puberty; whereas leptin levels continue to rise in girls, leptin levels decline sharply in boys.27 We speculate that progression of puberty in boys might require a decrease in leptin levels, which may be blunted among obese boys.

Another possible mechanism for this association in boys may be related to increased estradiol production. In contrast to females, obese males have greater elevations of estradiol levels compared with their normal-weight counterparts,28,29 likely related to increased activity of aromatase—the enzyme responsible for conversion of androgens to estradiol within adipose tissue.28 Estradiol has been shown in adult men to exert a negative feedback control on both the hypothalamus and pituitary. This results in decreases in both gonadotropin-releasing hormone pulse frequency and pituitary responsiveness to gonadotropin-releasing hormone,30,31 contributing to infertility in obese adult men.32 Therefore, it is possible that excess estradiol levels in boys with greater body fat mass may exert negative feedback on the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis in an analogous fashion, leading to a later onset of puberty. However, we do note that one study did not find differences in estradiol levels between obese and nonobese boys,33 although it was a small study that included only 6 obese boys. Furthermore, we note that the physical onset of puberty is not necessarily indicative of pubertal hormone secretion in the absence of pubertal progression. Future population-based studies to better characterize the relationship between body fat and timing of pubertal onset and progression in boys are needed and will require physiological measurements of a variety of hormones, including leptin and estradiol, to better understand the mechanisms that lead to pubertal initiation and progression in boys vs girls.

We recognize that there are multiple outcome measures for assessing puberty in boys. In-depth approaches to measuring puberty include testicular ultrasonography and serum testosterone measurement, which are outside the scope of the data collection for large, longitudinal, population-based cohorts. Puberty may also be measured via Tanner genitalia staging or assessment of testicular volume by palpation and comparison with the Prader orchidometer. Although testicular volume assessment is preferred by some investigators,34 the reliability and validity of this method, even among experienced pediatric endocrinologists, has been called into question.35 For that reason, we elected to use Tanner genitalia staging as our outcome measure of puberty.

We note that most boys in our cohort had onset of puberty by age 11.5 years, which is consistent with data previously published by Herman-Giddens et al,36 who evaluated the timing of secondary sexual characteristics in a representative sample of US boys. They found that the prevalence of Tanner stage 2 or greater genital development was reached by approximately 90% of boys by age 12 years, which would be consistent with the prevalence of puberty among our cohort. Furthermore, they reported a median age of 10.1 years for transition into Tanner stage 2 puberty as assessed by genitalia staging. In contrast, Biro et al37 reported a mean age of 12.2 years for pubertal initiation; however, the study by Biro and colleagues used a measure of puberty based on both testicular and pubic hair development, making comparison difficult as other studies have shown that pubic hair development generally lags behind genital pubertal development.36

It is unlikely that assignment of Tanner genitalia stage in our cohort was influenced by pubarche (pubic hair growth), which is due to the turning on of the adrenal gland in boys,38 as examiners assessed puberty and pubarche as separate outcome measures. Subcutaneous tissue could theoretically obscure the view of the genitalia in morbidly obese children, leading to misclassification. However, the mean BMI z score of boys in the highest trajectory group was 1.84, which is unlikely to be severe enough to lead to significant misclassification of the Tanner stage of male genitalia. Furthermore, if there was misclassification related to this issue, we would have expected lower rates of puberty compared with estimates of the timing of puberty from nationally representative samples.

There were limitations to our study. Although boys in our sample had a slightly lower BMI than those without height, weight, and pubertal measurements, the fact that we identified an association within our sample would suggest that our findings are relatively robust. We were unable to perform subgroup analyses by race given the small number of children classified as nonwhite. Body fat mass was assessed with BMI, a surrogate measure of adiposity, and studies have found that the relationship between body fat and BMI may vary depending on sex and race as well as overall percentage of body fat. Future studies might consider using more in-depth measurements of body fat such as dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry. Finally, the assessment of pubertal initiation in future studies would also benefit from the use of multiple simultaneous measures of puberty such as testicular ultrasonography in combination with serum testosterone measurement, which would provide convergent validity. Despite these limitations, the primary strength of our study lies in its large sample followed up longitudinally over nearly 10 years from early childhood. In addition, our sample included boys across the BMI spectrum and had significantly more socioeconomic and geographic diversity compared with prior cohorts.

This longitudinal study provides further evidence that higher BMI during early and middle childhood is not associated with earlier pubertal onset in boys, contrary to what is seen in girls. In fact, higher BMI in earlier childhood may be associated with and precede later onset of puberty among a population-based sample of US boys. Given the recent childhood obesity epidemic, additional studies are needed to further investigate the epidemiological link between body fat and pubertal initiation and progression in boys as well as the physiological mechanisms responsible.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Dr Lee was supported by grant K08DK082386 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and by the Clinical Sciences Scholars Program, University of Michigan. This work was supported by grant-in-aid 0750206Z from the American Heart Association Midwest Affiliate (Dr Lumeng).

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: None reported.

Additional Contributions: Ram Menon, MD, provided thoughtful comments during the preparation of the manuscript.

Author Contributions: Dr Lee had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: Lee, Bradley, and Lumeng. Acquisition of data: Corwyn, Bradley, and Lumeng. Analysis and interpretation of data: Lee, Kaciroti, Appugliese, Corwyn, and Lumeng. Drafting of the manuscript: Lee, Kaciroti, and Lumeng. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Lee, Appugliese, Corwyn, Bradley, and Lumeng. Statistical analysis: Lee, Kaciroti, Appugliese, Corwyn, and Lumeng. Obtained funding: Bradley and Lumeng. Administrative, technical, and material support: Bradley.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. JAMA. 2006;295(13):1549–1555. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morrison JA, Barton B, Biro FM, Sprecher DL, Falkner F, Obarzanek E. Sexual maturation and obesity in 9- and 10-year-old black and white girls: the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Growth and Health Study. J Pediatr. 1994;124(6):889–895. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)83176-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaplowitz PB, Slora EJ, Wasserman RC, Pedlow SE, Herman-Giddens ME. Earlier onset of puberty in girls: relation to increased body mass index and race. Pediatrics. 2001;108(2):347–353. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.2.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davison KK, Susman EJ, Birch LL. Percent body fat at age 5 predicts earlier pubertal development among girls at age 9. Pediatrics. 2003;111(4 pt 1):815–821. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.4.815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee JM, Appugliese D, Kaciroti N, Corwyn RF, Bradley RH, Lumeng JC. Weight status in young girls and the onset of puberty [published correction appears in Pediatrics. 2007;120(1):251] Pediatrics. 2007;119(3):e624–e630. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Y. Is obesity associated with early sexual maturation? a comparison of the association in American boys vs girls. Pediatrics. 2002;110(5):903–910. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.5.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. [Accessed January 12, 2006];The NICHD Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development. http://secc.rti.org/

- 8.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS, et al. 2000 CDC Growth Charts for the United States: methods and development. Vital Health Stat. 2002;11(246):1–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mantzoros CS, Flier JS, Rogol AD. A longitudinal assessment of hormonal and physical alterations during normal puberty in boys, V: rising leptin levels may signal the onset of puberty. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82(4):1066–1070. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.4.3878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herman-Giddens ME, Slora EJ, Wasserman RC, et al. Secondary sexual characteristics and menses in young girls seen in office practice: a study from the Pediatric Research in Office Settings network. Pediatrics. 1997;99(4):505–512. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.4.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. [Accessed November 2, 2007];Physical examination, 111/2 year visit. http://secc.rti.org/display.cfm?t=m&i=Chapter_76_5.

- 12.Adair LS. Size at birth predicts age at menarche. [Accessed May 1, 2008];Pediatrics. 2001 107(4):e59. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.4.e59. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/content/full/107/4/e59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagin D. Group-Based Modeling of Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frisch RE, McArthur JW. Menstrual cycles: fatness as a determinant of minimum weight for height necessary for their maintenance or onset. Science. 1974;185(4155):949–951. doi: 10.1126/science.185.4155.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hammar SL, Campbell MM, Campbell VA, et al. An interdisciplinary study of adolescent obesity. J Pediatr. 1972;80(3):373–383. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(72)80493-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laron Z, Ben-Dan I, Shrem M, Dickerman Z, Lilos P. Puberty in simple obese boys and girls. In: Cacciari E, Laron Z, Raiti S, editors. Obesity in Childhood. London, England: Academic Press; 1978. pp. 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun SS, Schubert CM, Liang R, et al. Is sexual maturity occurring earlier among US children? J Adolesc Health. 2005;37(5):345–355. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Biro FM, Khoury P, Morrison JA. Influence of obesity on timing of puberty. Int J Androl. 2006;29(1):272–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2005.00602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vizmanos B, Marti-Henneberg C. Puberty begins with a characteristic subcutaneous body fat mass in each sex. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2000;54(3):203–208. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Denzer C, Weibel A, Muche R, Karges B, Sorgo W, Wabitsch M. Pubertal development in obese children and adolescents. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31(10):1509–1519. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buyken AE, Karaolis-Danckert N, Remer T. Association of prepubertal body composition in healthy girls and boys with the timing of early and late pubertal markers. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89(1):221–230. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sandhu J, Ben-Shlomo Y, Cole TJ, Holly J, Davey Smith G. The impact of childhood body mass index on timing of puberty, adult stature and obesity: a follow-up study based on adolescent anthropometry recorded at Christ’s Hospital (1936–1964) Int J Obes (Lond) 2006;30(1):14–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.He Q, Karlberg J. BMI in childhood and its association with height gain, timing of puberty, and final height. Pediatr Res. 2001;49(2):244–251. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200102000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silventoinen K, Haukka J, Dunkel L, Tynelius P, Rasmussen F. Genetics of pubertal timing and its associations with relative weight in childhood and adult height: the Swedish Young Male Twins Study. Pediatrics. 2008;121(4):e885–e891. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vignolo M, Naselli A, Di Battista E, Mostert M, Aicardi G. Growth and development in simple obesity. Eur J Pediatr. 1988;147(3):242–244. doi: 10.1007/BF00442687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clayton PE, Gill MS, Hall CM, Tillmann V, Whatmore AJ, Price DA. Serum leptin through childhood and adolescence. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1997;46(6):727–733. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.1997.2081026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blum WF, Englaro P, Hanitsch S, et al. Plasma leptin levels in healthy children and adolescents: dependence on body mass index, body fat mass, gender, pubertal stage, and testosterone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82(9):2904–2910. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.9.4251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schneider G, Kirschner MA, Berkowitz R, Ertel NH. Increased estrogen production in obese men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1979;48(4):633–638. doi: 10.1210/jcem-48-4-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jensen TK, Andersson AM, Jorgensen N, et al. Body mass index in relation to semen quality and reproductive hormones among 1558 Danish men. Fertil Steril. 2004;82(4):863–870. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.03.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bagatell CJ, Dahl KD, Bremner WJ. The direct pituitary effect of testosterone to inhibit gonadotropin secretion in men is partially mediated by aromatization to estradiol. J Androl. 1994;15(1):15–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hayes FJ, Seminara SB, Decruz S, Boepple PA, Crowley WF., Jr Aromatase inhibition in the human male reveals a hypothalamic site of estrogen feedback. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(9):3027–3035. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.9.6795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pauli EM, Legro RS, Demers LM, Kunselman AR, Dodson WC, Lee PA. Diminished paternity and gonadal function with increasing obesity in men. Fertil Steril. 2008;90(2):346–351. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.06.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klein KO, Larmore KA, de Lancey E, Brown JM, Considine RV, Hassink SG. Effect of obesity on estradiol level, and its relationship to leptin, bone maturation, and bone mineral density in children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83 (10):3469–3475. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.10.5204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reiter EO, Lee PA. Have the onset and tempo of puberty changed? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155(9):988–989. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.9.988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rivkees SA, Hall DA, Boepple PA, Crawford JD. Accuracy and reproducibility of clinical measures of testicular volume. J Pediatr. 1987;110(6):914–917. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(87)80412-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Herman-Giddens ME, Wang L, Koch G. Secondary sexual characteristics in boys: estimates from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III, 1988–1994. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155(9):1022–1028. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.9.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Biro FM, Lucky AW, Huster GA, Morrison JA. Pubertal staging in boys. J Pediatr. 1995;127(1):100–102. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(95)70265-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ibáñez L, Dimartino-Nardi J, Potau N, Saenger P. Premature adrenarche: normal variant or forerunner of adult disease? Endocr Rev. 2000;21(6):671–696. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.6.0416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]