Abstract

The treatment of malignant brain tumors remains a challenge. Stem cell technology has been applied in the treatment of brain tumors largely because of the ability of some stem cells to infiltrate into regions within the brain where tumor cells migrate as shown in preclinical studies. However, not all of these efforts can translate in the effective treatment that improves the quality of life for patients. Here, we perform a literature review to identify the problems in the field. Given the lack of efficacy of most stem cell-based agents used in the treatment of malignant brain tumors, we found that stem cell distribution (i.e., only a fraction of stem cells applied capable of targeting tumors) are among the limiting factors. We provide guidelines for potential improvements in stem cell distribution. Specifically, we use an engineered tissue graft platform that replicates the in vivo microenvironment, and provide our data to validate that this culture platform is viable for producing stem cells that have better stem cell distribution than with the Petri dish culture system.

Keywords: Stem cells, Malignant brain tumors, Engineered tissue graft, Organotypic slice model

Core tip: Neural stem cells can target malignant brain tumors in preclinical models; however, clinical trials show dismal efficacy. We reviewed the literature and .found that only a small fraction of applied stem cells can move toward tumors while the majority of stem cells cannot reach the target tumor. To fill in the gap in stem cell technology, we propose a solution to train stem cells in a native tissue environment, allowing them to move through tissue barriers and arrive at the target tumor.

INTRODUCTION

Malignant brain tumors are devastating to patients

Billions of dollars have been spent since United States President Richard Nixon declared the “war on cancer.” Understanding the molecular biology of cancer led to gain better survival in certain cancers, such as childhood leukemia. However, survival in solid tumors has not improved since the 1970s. New studies revealed that unexpected factors such as intratumoral heterogeneity[1] and clonal evolution force us to realize that classical therapies cannot fully address the tumor subclonal switch mechanism that allow tumors to escape therapy[2]. This includes chemotherapy drug temozolomide-driven evolution of recurrent glioma[3] into a restricted subclonal cell population of drug-resistance[4]. Ineffective cancer treatment results in mortality and economic burden: one-third of 2007 healthcare dollars (total: $686 billion) was spent on 1.4 million cancer patients in the United States[5-7]. Some pediatric malignant brain tumor patient costs $67887, which is 200 times as much as a demographical control, $277[5,8]. It is devastating, considering that the fortunate survivors suffer cognitive changes, cognitive deficiency that challenges the quality of life of both patients and their care givers[9].

LIMITATION OF CURRENT STANDARD TREATMENT

Cancer treatment is largely unsuccessful due to current blindfolded anti-cancer strategic and tactical issues in the fight. Surgical resection allows glioma patients survive the traumatic attack; however, surgery alone cannot clear the residual infiltrative glioma. Malignant brain tumors disseminate widely to distant regions of normally functioning tissues[10]. Thus, surgery in conjunction with chemotherapy and radiation therapy still cannot eradicate residual tumors[11,12].

ADVERSE SIDE EFFECTS OF STANDARD THERAPIES

Chemotherapy and radiation therapy do not strictly discriminate tumor cells from normal cells, resulting in adverse effects. Survivors of current standard brain tumor treatment show neurological, cognitive, endocrine sequelae, and metabolic side effects[11,13-20]. These side effects result from the cumulative effects of pre-treatment injury caused by the growing tumor, the adverse impact of surgery and from adjuvant therapeutics (chemotherapy and radiation therapy)[21]. The surgical removal of the initial tumor followed with adjuvants (radiation plus chemotherapy) may awaken the dormant clones of the primary tumor and these cells then grow to form a secondary tumor (Figure 1) as the dormant cells go through switchboard signaling to become dominate clones of cancer[2]. These glioma residues grow back, leading to recurrent incurable and metastatic cancer. Adjuvant therapies (Local radiotherapy, chemical sensitizers, gene therapy) did not provide any survival advantage in clinical trials.

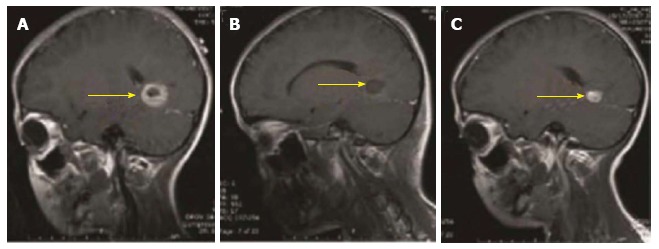

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging graphs illustrate the presence, removal, and reappearance of a glioblastoma patient (yellow arrow: tumor mass). A: Pre-operation, visualizing the presence of the tumor; B: Post-surgery, visualizing disappearance of the tumor; C: 3-mo post-surgery, visualizing the reappearance of the tumor.

GENETIC PROFILING

Genetic profiling shows the potential genetic risk factors for patients and a way to predict how a patient may react with a given tumor treatment. Across 12 tumor types in 2928 out of 3277 patients, The Cancer Genome Atlas Network (TCGA) analyzed 10281 somatic alterations[22]. This TCGA data set predicts patient survival when applying therapies useful in one cancer type to other cancer types. This molecular profile-based prediction of therapeutic efficacy may imply a new classification system different from the previous organ-based tumor classification system[23].

For example, the analysis of somatic mutations in glioblastoma multiforme (GBM)[24] helped establish Proneural, Neural, Classical, and Mesenchymal subtypes[24]. Each subtype, with its own molecular stratification (PDGFRA, IDH1, EGFR, and NF1 gene), can exhibit specific drug targets that minimize adverse effects and enhance efficacy. Another study shows that recurrent H3F3A mutations are further characterized into six methylation patterns[25]. The methylation patterns help design epigenetic-pattern-specific targeted therapies[25]. Molecular changes in BRAF, RAF1, FGFR1, MYB, MYBL1, H3F3A, and ATRX were identified in 151 low-grade gliomas (LGGs)[26]. Another study defined recurrent activating mutations in FGFR1, PTPN11, and NTRK2 genes in LGGs[27]. The mutations imply some targeted therapies, e.g., specific inhibitors against FGFR1 autophosphorylation can block MAPK/ERK/PI3K, preventing cancer cells from proliferating.

These mutations can help focus targeted therapies for patients. Temozolomide (TMZ) and radiation, increase survival for patients with Classical or Mesenchymal subtypes but not with Proneural subtype[24]. However, chemotherapy can activate chemoresistent cancer cells. TMZ drives a subset of endogenous cells out of their quiescent subventricular zone to develop to a new tumor[4]. Evidence shows that TP53, ATRX, SMARCA4, and BRAF mutations in the initial tumor but were undetected at recurrence, suggesting new mutations occur upon drug-driven tumor evolution. TMZ-activated RB (retinoblastoma) and Akt-mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) mutations led to recurrent tumors[3]. New strategy to address these therapy-driven detrimental effects in a real-time manner is needed.

EMERGING THERAPIES

Neural stem cells (NSCs) possess the tumor-tracking capacity as shown in preclinical models[28]. NSCs modulate the brain tumor microenvironment[29-32]. Other candidate stem cells include HSCs[33], BM-MSC[34], and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC)[35]. Because iPSC technology enables autologous transplantation allowing immune compatibility with a host immune system (Figure 2), iPSCs are proposed for replacement therapy in certain diseases[36]. However, potential immune rejection of these autologous iPSCs remains to be tested in clinical trials[37].

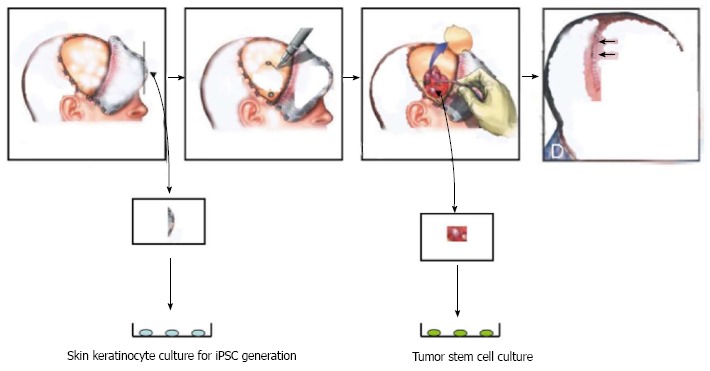

Figure 2.

Personalized treatment of brain tumors by using autologous stem cells (induced pluripotent stem cells) through the induced pluripotent stem cells strategy for treating brain tumors. During surgery, a piece of skin is obtained to generate induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) while tumor cells are processed to obtain tumor stem cells (TSCs). The iPSCs are used to take therapy specific to autologous TSCs.

These stem cells could be engineered as delivery vehicles for therapeutic agents[38] such as antibody[39], oncolytic adenoviral virotherapy[40], and prodrug therapy[41]. NSCs inhibit glioma proliferation in vivo and in vitro[42]. Intracranial tumors activate endogenous NSCs to migrate towards neoplastic target lesions[43,44].

Evidence shows that BM-MSCs work in the same fashion as NSCs[34]. MSCs exhibit tropism towards gliomas[45-47]). MSCs locally produce IFN-β that suppresses cancer cells[48].

CLINICAL TRIALS SHOW DISCREPANCIES

Serving to reconstitute hematopoietic and immune function, some stem cells act as a salvage therapy for surgery, radiation therapy, and high dose chemotherapy. For example, patients rely on autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation to replenish immune capacity against recurrent cancer after surgery and chemotherapy[49]. Currently, 240 studies on “stem cell therapy of cancer” exist in mostly Phases I/II clinical trials (See http://clinicaltrial.gov, accessed on August 22, 2014) using HSCs and BM-MSCs. Interestingly, genetically modified NSCs orchestrate flucytosine and leucovorin calcium in treating gliomas [ClinicalTrials-gov identifier NCT02015819 (2014)]. The genetically modified NSCs carry the gene for Escherichia coli (E. coli) flucytosine that sensitizes cancer to chemotherapy while leucovorin calcium helps stop cancer cells from dividing. The project of ClinicalTrials-gov Identifier NCT01540175 aimed at replenishing an immune system (T cell, B cell, and NK cell compartment) on autologous transplant to the baseline values, representing an innovation that is expected to replace the conventional HSC transplantation. Phase I trials using tumor dendritic vaccines evaluated the side effects of vaccine therapy on recurrent GBM (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00890032 - tumor cells/dendritic cells; ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01171469-tumor stem cells; assessed on August 22, 2014), a potential that a real-time anti-cancer system is established in vivo to monitor cancer growth. These everlasting vaccines are expected to set up an immune response to stop cancer.

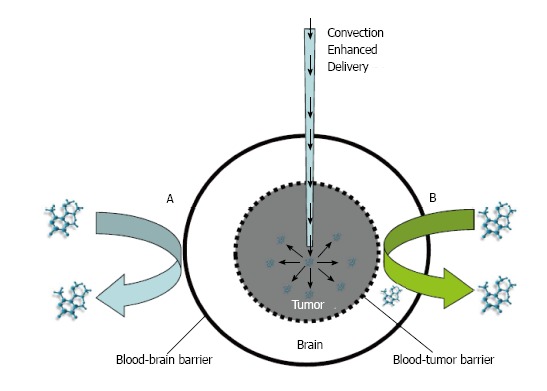

Discrepancies of efficacy occurred in all these clinical trials and efforts have been made to explain what roadblocks are in the way for achieving consistent efficacy. Roadblocks for stem cells to reach the site of the tumor include the blood brain barrier (BBB) and the brain tumor barrier (BTB) (Figure 3). Most intravenously administered NSCs cannot cross BBB and BTB but only a few do[7]. These roadblocks must be removed to clear that path for success of stem cell therapy for cancer[7]. Specifically, we need to cultivate potentiated stem cells to be potent to tranverse these roadblocks.

Figure 3.

Convection enhanced delivery of therapy to overcome two barriers of brain tumors. A: Systemic delivery of drugs blocked from entry into the brain by the blood brain barrier; B: Drug delivery inhibited by the brain-tumor barrier. This convection enhanced delivery can be used to deliver neural stem cells locally onto a tumor.

THE NEED TO FIND WAYS OF IMPROVING THE POTENCY OF STEM CELLS

What qualities for stem cells could allow therapeutic effectiveness? The ideal stem cells should provide: (1) long-distance inter-organ autopilot traveling to surgically inaccessible tumors, ideally when administrated by peripheral intravenous injection; (2) accuracy in eliminating tumors without adversely affecting normal organs; (3) capability of suppressing primary and metastatic tumor; and (4) memory so that recurrence never occurs.

Components of an inter-organ movable vehicle for targeting cancer

(1) The therapeutic agent shows the maximum anti-cancer efficacy with the minimum adverse effect; (2) The vehicle should protect the therapeutic agent for its potency and specificity; and (3) The vehicle possesses the ability to home in on targets.

Stem cell therapy provides the essential components of such a defined therapeutic agent, as fellows.

The therapeutic agent: Therapeutic benefits of stem cells include (1) regenerative action; (2) neuroprotective modulation; and (3) immune regulation. The BM-MSC transplantation induces survival and proliferation of host neurons through secreting BDNF, β-NGF, and adhesion molecules[50]. Stem cells can serve as a “Trojan Horse” for transplantation of cancer drugs[50,51].

The autopilot vehicle: NSCs can detect a target (homing) via chemokines produced by tumors (Figure 4, Li et al[7] 2008), the capacity like a self-driving vehicle. Following this chemokine gradient, NSCs can move through tissue barriers such as the blood brain barrier and brain tumor barrier (Figure 3) to reach their target tissue. We need to determine the therapeutic window of stem cell development, the window of stem cell development that is capable for targeting tumors[52]. If stem cells develop outside of a window period, thereby lose the ability of migrating toward tumors because their migration-required molecules are down regulated[53].

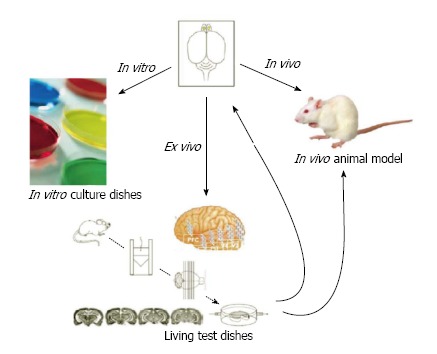

Figure 4.

Three ways to drug testing: In vitro Petri dishes, in vivo animal model and ex vivo engineered tissue graft. An engineered tissue graft has an intrinsic character of native brain environment.

Delivery system: Stem cell delivery for cancer remains to be defined. For brain tumors, we can use a stereotactic injection for a specific brain region. Mooney and colleagues show that NSCs can facilitate the tumor-selective distribution of nanoparticles, a drug-loading system that is promising in cancer therapy[54]. We can apply CED (convection-enhanced delivery) to deliver stem cells across the blood-brain barrier and the brain-tumor barrier (Figure 3). We need further to track down stem cell migration in vivo by using a real-time tracking system as we discussed previously[55], a way that can address possible adverse effects.

A PROBLEM IN STEM CELL TRANSPLANTATION AND ITS SOLUTION

Only marginal effects can be observed in stem cell therapy despite exciting potency shown in some animal models[52]. In fact, it is a game of number wrestling between good stem cells and tumor cells[52,53]. Current stem cell experiments in mouse models involve transplantation of millions of stem cells, with only some migrating toward tumors, a few surviving at the tumor site, and rare engraftment[52,53]. The rest of the non-migratory stem cells are detrimental to a recipient, because these can induce the formation of heterogeneous tumor and inflammation. Thus, we must enable stem cells to pass certain uniform quality control standard so that they can fulfill their designed purpose of targeting brain tumors.

TRAIN STEM CELLS IN AN ORGAN-SPECIFIC MICROENVIRONMENT

The low number of stem cells capable of migrating toward tumors derived from Petri dish culture system as shown in preclinical and clinical studies may result from the following differences: (1) the source of stem cells; (2) methods of stem cell culture; (3) differentiation status (percentage of differentiated cells); (4) the age of the stem cells in culture; and (5) the nature of a tumor[34].

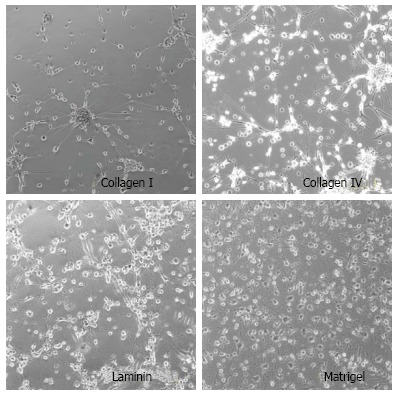

We found that culture matrix makes a difference in stem cell characteristics. NSCs behave differently in coated Petri culture plates (Figure 5). NSCs show much more neurite growth on Matrigel-coated Petri polystyrene plates than on other adhesion molecule-coated plates (Collagen I, Collagen IV, or Laminine). Nevertheless, none of these adhesion molecules can generate uniform populations of stem cells. We have designed an engineered tissue graft model as a universal training platform to address the issue of heterogeneity of cultured stem cells[7]. An engineered tissue graft (ETG) provides a native organ microenvironment closer to an in vivo model and very different from an in vitro Petri dish (polystyrene plates) system (Figure 4)[56]. This ETG model can be generated from patient specific brain tumor specimens for autologous characterization of therapeutic in vivo-like trials of a new drug (Figure 6). This ETG material was made according to our patented technology - an ETG generated by seeding brain tumor stem cells onto slice cultures of patients' pathological brain tissue harvested during tumor resection - which preserved the pathological micro-environment[52].

Figure 5.

Stem cells cultured on Petri dishes coated with different matrix, showing non-physiologically relevant morphology with a few neurite growth.

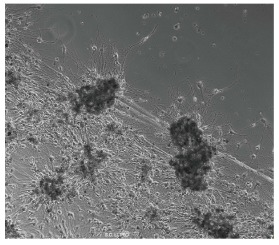

Figure 6.

An engineered brain tumor tissue graft in culture, showing tumor lesions (black dots) that attract stem cells to engraft.

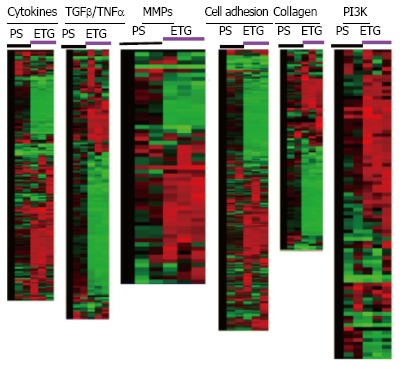

Such a culture platform can train stem cells to fulfill the purpose of targeting brain tumor cells as they help generate uniform neurite formation in culture that is essential for brain-tumor-targeted migration (Figure 7). These ETG-based matrix produced cells express molecular markers different from cells cultured on polystyrene plates (PS) as shown in gene arrays (Figure 8). We can obtain a morphologically uniform population of stem cells in an ETG microenvironment (Figure 9). Optimizing the chemokine responsiveness (chemokine receptors expressed by stem cells) and upregulating matrix-remodeling matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are essential: Both chemokine receptor and MMPs are well expressed in cells with ETG but not with Petri dish culture system[7]. Additionally, to overcome the problem of immune response, we have designed autologous iPSCs (induced pluripotent stem cells) for certain patient tumors (Figure 3), a dual system that can mutually promote each other for better efficacy. These trained stem cells can act as an autopilot vehicle that is self-driven to its target (Li et al[7], 2008, Figure 5). This ETG can be engineered to mimic the in vivo fluidic microenvironment with the continuous flow of physicochemical buffer, the microfluidic system that can be coupled with real-time imaging for analysis of cell development as the quality control (QC) as detailed in a recent report[57]. In the future, a QC system should be implemented for the structural and functional characterization of stem cell production before using for transplantation. This ETG could be scaled for automatic studies.

Figure 7.

Neural stem cells cultured on the engineered tissue graft showing abundant neurite formation and neuronal morphology.

Figure 8.

Data analysis of Affymetrix Gene Chip arrays for pediatric derived brain tumor stem cells grown on engineered tissue graftmatrix-like surface or polystyrene dish. The cells were grown on engineered tissue graft (ETG) matrix-like surface or polystyrene dish (PS) for 7 d for gene chip array analysis showing gene clusters on different functional group of signaling pathways. Notice that red color represents the highest expression, green color for medium expression, and black for lowest expression. MMPs: Matrix-remodeling matrix metalloproteinases; TNF: Tumor necrosis factors; TGF: Transforming growth factor.

Figure 9.

An engineered tissue graft is used as the designer matrix to train stem cells to target a specific tumor as shown for production of a morphologically homogeneous population of stem cells.

CONCLUSION

Stem cell therapies of brain tumors are being investigated preclinically; however, little efficacy has been found in clinical trials. We reviewed the literature and found that heterogeneous stem cell populations were made using artificial matrices, a roadblock to achieve consistent efficacy. We provide an ETG as a uniform platform to train stem cells for attacking tumor cells, which may address the discrepancies of current clinical trials.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Maria Minon, MD; Saul Puszkin, PhD; Michael P Lisanti, MD-PhD; Richard G Pestell, MD-PhD; Joan S Brugge, PhD; Robert A Koch, PhD; Philip H Schwartz, PhD; for their support and enthusiasm.

Footnotes

Supported by The CHOC Children’s Foundation, CHOC Neuroscience Institute, CHOC Research Institute, The Austin Ford Tribute and Keck Foundation; by The United States National Institutes of Health, 1R01CA164509-01; and The United States National Science Foundation, CHE-1213161

P- Reviewer: Lichtor T, Mueller WC S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

References

- 1.Gerlinger M, Rowan AJ, Horswell S, Larkin J, Endesfelder D, Gronroos E, Martinez P, Matthews N, Stewart A, Tarpey P, et al. Intratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencing. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:883–892. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li SC, Lee KL, Luo J. Control dominating subclones for managing cancer progression and posttreatment recurrence by subclonal switchboard signal: implication for new therapies. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21:503–506. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson BE, Mazor T, Hong C, Barnes M, Aihara K, McLean CY, Fouse SD, Yamamoto S, Ueda H, Tatsuno K, et al. Mutational analysis reveals the origin and therapy-driven evolution of recurrent glioma. Science. 2014;343:189–193. doi: 10.1126/science.1239947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen J, Li Y, Yu TS, McKay RM, Burns DK, Kernie SG, Parada LF. A restricted cell population propagates glioblastoma growth after chemotherapy. Nature. 2012;488:522–526. doi: 10.1038/nature11287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradley S, Sherwood PR, Donovan HS, Hamilton R, Rosenzweig M, Hricik A, Newberry A, Bender C. I could lose everything: understanding the cost of a brain tumor. J Neurooncol. 2007;85:329–338. doi: 10.1007/s11060-007-9425-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fisk GJ, Inokuma MS. Endoderm cells from human embryonic stem cells. In: United States Patent US7326572B2., editor. USA: Geron Corporation; 2008. pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li SC, Loudon WG. A novel and generalizable organotypic slice platform to evaluate stem cell potential for targeting pediatric brain tumors. Cancer Cell Int. 2008;8:9. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-8-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kutikova L, Bowman L, Chang S, Long SR, Thornton DE, Crown WH. Utilization and cost of health care services associated with primary malignant brain tumors in the United States. J Neurooncol. 2007;81:61–65. doi: 10.1007/s11060-006-9197-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whiting DL, Simpson GK, Koh ES, Wright KM, Simpson T, Firth R. A multi-tiered intervention to address behavioural and cognitive changes after diagnosis of primary brain tumour: a feasibility study. Brain Inj. 2012;26:950–961. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2012.661912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Louis DN. Molecular pathology of malignant gliomas. Annu Rev Pathol. 2006;1:97–117. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.1.110304.100043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knab B, Connell PP. Radiotherapy for pediatric brain tumors: when and how. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2007;7:S69–S77. doi: 10.1586/14737140.7.12s.S69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loudon W, Sutton L. Childhood Malignant Gliomas. Contemp Neurosurg. 2000;22:1–9. Available from: http: //journals.lww.com/contempneurosurg/Abstract/2000/10010/Childhood_Malignant_Gliomas.1.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li SC, Loudon WG. Stem Cell Therapy for Paediatric Malignant Brain Tumours: The Silver Bullet? Oncology News (UK) 2008;3:10–14. Available from: http://www.oncologynews.biz/pdf/jun_jul_08/ONJJ08_stemcell.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brière ME, Scott JG, McNall-Knapp RY, Adams RL. Cognitive outcome in pediatric brain tumor survivors: delayed attention deficit at long-term follow-up. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50:337–340. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meeske KA, Patel SK, Palmer SN, Nelson MB, Parow AM. Factors associated with health-related quality of life in pediatric cancer survivors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;49:298–305. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zebrack BJ, Gurney JG, Oeffinger K, Whitton J, Packer RJ, Mertens A, Turk N, Castleberry R, Dreyer Z, Robison LL, et al. Psychological outcomes in long-term survivors of childhood brain cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:999–1006. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Macedoni-Luksic M, Jereb B, Todorovski L. Long-term sequelae in children treated for brain tumors: impairments, disability, and handicap. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2003;20:89–101. doi: 10.1080/0880010390158595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benesch M, Lackner H, Moser A, Kerbl R, Schwinger W, Oberbauer R, Eder HG, Mayer R, Wiegele K, Urban C. Outcome and long-term side effects after synchronous radiochemotherapy for childhood brain stem gliomas. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2001;35:173–180. doi: 10.1159/000050418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foreman NK, Faestel PM, Pearson J, Disabato J, Poole M, Wilkening G, Arenson EB, Greffe B, Thorne R. Health status in 52 long-term survivors of pediatric brain tumors. J Neurooncol. 1999;41:47–53. doi: 10.1023/a:1006145724500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanai N, Mirzadeh Z, Berger MS. Functional outcome after language mapping for glioma resection. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:18–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vernooij MW, Ikram MA, Tanghe HL, Vincent AJ, Hofman A, Krestin GP, Niessen WJ, Breteler MM, van der Lugt A. Incidental findings on brain MRI in the general population. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1821–1828. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yuan Y, Van Allen EM, Omberg L, Wagle N, Amin-Mansour A, Sokolov A, Byers LA, Xu Y, Hess KR, Diao L, et al. Assessing the clinical utility of cancer genomic and proteomic data across tumor types. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:644–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weinstein JN, Collisson EA, Mills GB, Shaw KR, Ozenberger BA, Ellrott K, Shmulevich I, Sander C, Stuart JM. The Cancer Genome Atlas Pan-Cancer analysis project. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1113–1120. doi: 10.1038/ng.2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Verhaak RG, Hoadley KA, Purdom E, Wang V, Qi Y, Wilkerson MD, Miller CR, Ding L, Golub T, Mesirov JP, et al. Integrated genomic analysis identifies clinically relevant subtypes of glioblastoma characterized by abnormalities in PDGFRA, IDH1, EGFR, and NF1. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:98–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sturm D, Witt H, Hovestadt V, Khuong-Quang DA, Jones DT, Konermann C, Pfaff E, Tönjes M, Sill M, Bender S, et al. Hotspot mutations in H3F3A and IDH1 define distinct epigenetic and biological subgroups of glioblastoma. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:425–437. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang J, Wu G, Miller CP, Tatevossian RG, Dalton JD, Tang B, Orisme W, Punchihewa C, Parker M, Qaddoumi I, et al. Whole-genome sequencing identifies genetic alterations in pediatric low-grade gliomas. Nat Genet. 2013;45:602–612. doi: 10.1038/ng.2611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones DT, Hutter B, Jäger N, Korshunov A, Kool M, Warnatz HJ, Zichner T, Lambert SR, Ryzhova M, Quang DA, et al. Recurrent somatic alterations of FGFR1 and NTRK2 in pilocytic astrocytoma. Nat Genet. 2013;45:927–932. doi: 10.1038/ng.2682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aboody KS, Brown A, Rainov NG, Bower KA, Liu S, Yang W, Small JE, Herrlinger U, Ourednik V, Black PM, et al. Neural stem cells display extensive tropism for pathology in adult brain: evidence from intracranial gliomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:12846–12851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.23.12846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Müller FJ, Snyder EY, Loring JF. Gene therapy: can neural stem cells deliver? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:75–84. doi: 10.1038/nrn1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bierings M, Nachman JB, Zwaan CM. Stem cell transplantation in pediatric leukemia and myelodysplasia: state of the art and current challenges. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2007;2:53–63. doi: 10.2174/157488807779317035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mapara KY, Stevenson CB, Thompson RC, Ehtesham M. Stem cells as vehicles for the treatment of brain cancer. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2007;18:71–80, ix. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sagar J, Chaib B, Sales K, Winslet M, Seifalian A. Role of stem cells in cancer therapy and cancer stem cells: a review. Cancer Cell Int. 2007;7:9. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-7-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hipp J, Atala A. Sources of stem cells for regenerative medicine. Stem Cell Rev. 2008;4:3–11. doi: 10.1007/s12015-008-9010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li SC, Wang L, Jiang H, Acevedo J, Chang AC, Loudon WG. Stem cell engineering for treatment of heart diseases: potentials and challenges. Cell Biol Int. 2009;33:255–267. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li SC, Jin Y, Loudon WG, Song Y, Ma Z, Weiner LP, Zhong JF. Increase developmental plasticity of human keratinocytes with gene suppression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:12793–12798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100509108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fox IJ, Daley GQ, Goldman SA, Huard J, Kamp TJ, Trucco M. Stem cell therapy. Use of differentiated pluripotent stem cells as replacement therapy for treating disease. Science. 2014;345:1247391. doi: 10.1126/science.1247391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pearl JI, Kean LS, Davis MM, Wu JC. Pluripotent stem cells: immune to the immune system? Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:164ps25. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Danks MK, Yoon KJ, Bush RA, Remack JS, Wierdl M, Tsurkan L, Kim SU, Garcia E, Metz MZ, Najbauer J, et al. Tumor-targeted enzyme/prodrug therapy mediates long-term disease-free survival of mice bearing disseminated neuroblastoma. Cancer Res. 2007;67:22–25. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frank RT, Aboody KS, Najbauer J. Strategies for enhancing antibody delivery to the brain. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1816:191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ahmed AU, Thaci B, Tobias AL, Auffinger B, Zhang L, Cheng Y, Kim CK, Yunis C, Han Y, Alexiades NG, et al. A preclinical evaluation of neural stem cell-based cell carrier for targeted antiglioma oncolytic virotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:968–977. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aboody KS, Najbauer J, Metz MZ, D’Apuzzo M, Gutova M, Annala AJ, Synold TW, Couture LA, Blanchard S, Moats RA, et al. Neural stem cell-mediated enzyme/prodrug therapy for glioma: preclinical studies. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:184ra59. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Benedetti S, Pirola B, Pollo B, Magrassi L, Bruzzone MG, Rigamonti D, Galli R, Selleri S, Di Meco F, De Fraja C, et al. Gene therapy of experimental brain tumors using neural progenitor cells. Nat Med. 2000;6:447–450. doi: 10.1038/74710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Glass R, Synowitz M, Kronenberg G, Walzlein JH, Markovic DS, Wang LP, Gast D, Kiwit J, Kempermann G, Kettenmann H. Glioblastoma-induced attraction of endogenous neural precursor cells is associated with improved survival. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2637–2646. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5118-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Synowitz M, Kiwit J, Kettenmann H, Glass R. Tumor Young Investigator Award: tropism and antitumorigenic effect of endogenous neural precursors for gliomas. Clin Neurosurg. 2006;53:336–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Birnbaum T, Roider J, Schankin CJ, Padovan CS, Schichor C, Goldbrunner R, Straube A. Malignant gliomas actively recruit bone marrow stromal cells by secreting angiogenic cytokines. J Neurooncol. 2007;83:241–247. doi: 10.1007/s11060-007-9332-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sonabend AM, Dana K, Lesniak MS. Targeting epidermal growth factor receptor variant III: a novel strategy for the therapy of malignant glioma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2007;7:S45–S50. doi: 10.1586/14737140.7.12s.S45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sonabend AM, Ulasov IV, Tyler MA, Rivera AA, Mathis JM, Lesniak MS. Mesenchymal stem cells effectively deliver an oncolytic adenovirus to intracranial glioma. Stem Cells. 2008;26:831–841. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Studeny M, Marini FC, Champlin RE, Zompetta C, Fidler IJ, Andreeff M. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells as vehicles for interferon-beta delivery into tumors. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3603–3608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cheuk DK, Lee TL, Chiang AK, Ha SY, Chan GC. Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for high-risk brain tumors in children. J Neurooncol. 2008;86:337–347. doi: 10.1007/s11060-007-9478-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee JP, Jeyakumar M, Gonzalez R, Takahashi H, Lee PJ, Baek RC, Clark D, Rose H, Fu G, Clarke J, et al. Stem cells act through multiple mechanisms to benefit mice with neurodegenerative metabolic disease. Nat Med. 2007;13:439–447. doi: 10.1038/nm1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weidt C, Niggemann B, Kasenda B, Drell TL, Zänker KS, Dittmar T. Stem cell migration: a quintessential stepping stone to successful therapy. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2007;2:89–103. doi: 10.2174/157488807779317008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li SC, Han YP, Dethlefs BA, Loudon WG. Therapeutic window, a critical developmental stage for stem cell therapies. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2010;5:297–293. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li SC, Acevedo J, Wang L, Jiang H, Luo J, Pestell RG, Loudon WG, Chang AC. Mechanisms for progenitor cell-mediated repair for ischemic heart injury. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2012;7:2–14. doi: 10.2174/157488812798483449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mooney R, Weng Y, Tirughana-Sambandan R, Valenzuela V, Aramburo S, Garcia E, Li Z, Gutova M, Annala AJ, Berlin JM, et al. Neural stem cells improve intracranial nanoparticle retention and tumor-selective distribution. Future Oncol. 2014;10:401–415. doi: 10.2217/fon.13.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li SC, Tachiki LM, Luo J, Dethlefs BA, Chen Z, Loudon WG. A biological global positioning system: considerations for tracking stem cell behaviors in the whole body. Stem Cell Rev. 2010;6:317–333. doi: 10.1007/s12015-010-9130-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Engler AJ, Sen S, Sweeney HL, Discher DE. Matrix elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Cell. 2006;126:677–689. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bhatia SN, Ingber DE. Microfluidic organs-on-chips. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:760–772. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]