Abstract

Summary: MAGI is a web service for fast MicroRNA-Seq data analysis in a graphics processing unit (GPU) infrastructure. Using just a browser, users have access to results as web reports in just a few hours—>600% end-to-end performance improvement over state of the art. MAGI’s salient features are (i) transfer of large input files in native FASTA with Qualities (FASTQ) format through drag-and-drop operations, (ii) rapid prediction of microRNA target genes leveraging parallel computing with GPU devices, (iii) all-in-one analytics with novel feature extraction, statistical test for differential expression and diagnostic plot generation for quality control and (iv) interactive visualization and exploration of results in web reports that are readily available for publication.

Availability and implementation: MAGI relies on the Node.js JavaScript framework, along with NVIDIA CUDA C, PHP: Hypertext Preprocessor (PHP), Perl and R. It is freely available at http://magi.ucsd.edu.

Contact: j5kim@ucsd.edu

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are short, single-stranded and non–protein-coding RNAs, with an average size of 22 bases that silence target genes either by degradation of mRNA level or repression of a translated protein. miRNAs have generated great interest by the biomedical community because of their implications in human disease and development. The advent of high-throughput short-read sequencing has enabled comprehensive miRNA studies. There are several web services for miRNA-seq data analysis targeting the needs of non-technical users. Deep-sequencing Small RNA analysis Pipeline (DSAP) (Huang et al. 2010) quantifies known miRNAs, while miRAnalyzer (Hackenberg et al., 2011), Computational Platform analysis of Small RNA deep Sequencing data (CPSS) (Zhang et al., 2012) and wapRNA (Zhao et al., 2011) perform novel miRNA prediction and target prediction. mirTools (Zhu et al., 2010) add functional annotation, while omiRas (Muller et al., 2013) allows for upload of raw FASTQ files.

However, there are a number of issues that limit the adoption and usability of these services in real-world scenarios. Many of these tools incur significant file transfer and preprocessing overheads. Existing web services for miRNA-seq do not handle large FASTQ files. For instance, omiRas is limited to 2 GB inputs. Furthermore, because of a user’s browser or web server limitations, a user cannot upload multiple large files and the connection to the server may get lost during file transfers. A common work-around is to run command-line scripts that downsize the input before upload—a cumbersome and error-prone two-step approach that alienates non-technical users who may not have experience with complex Perl- or Python-based parsing scripts and their cryptic parameter settings. Additionally, prediction of miRNA targets is a time-consuming task that delays downstream analyses. Moreover, most tools do not provide a statistical test for novel miRNA differential expression; statistical quality control is limited, as base quality scores and summary statistics for aligned reads are ignored. Lastly, most tools generate simple static image plots, where in-depth analysis and interactive rendering are not possible.

2 DESCRIPTION

MAGI addresses these limitations by fully embracing the HTML5-technology with a Node.js-based web service backend for the analysis of miRNA sequencing data directly from FASTQ files. The results can later be retrieved and shared with others via a unique URL provided directly during the analysis or via email. To aid new users, we provide tutorial links to the web reports generated with peer-reviewed published data, including miRNA-seq in Kawasaki Disease (Shimizu et al., 2013). MAGI’s backend further incorporates graphics processing unit (GPU) devices to tremendously speed-up the analyses and deliver results in just a couple of hours instead of days. Open-source technologies, such as PHP, Perl and R running on top of a Linux platform drive the generation of a web report consisting of quality plots, alignment, pile-up charts of mapped reads, secondary structure of precursor miRNAs, differentially expressed miRNA between two groups, predicted miRNA target genes and enriched pathways. In this article, we introduce four novel features of MAGI. Technical details are provided in the Supplementary Material.

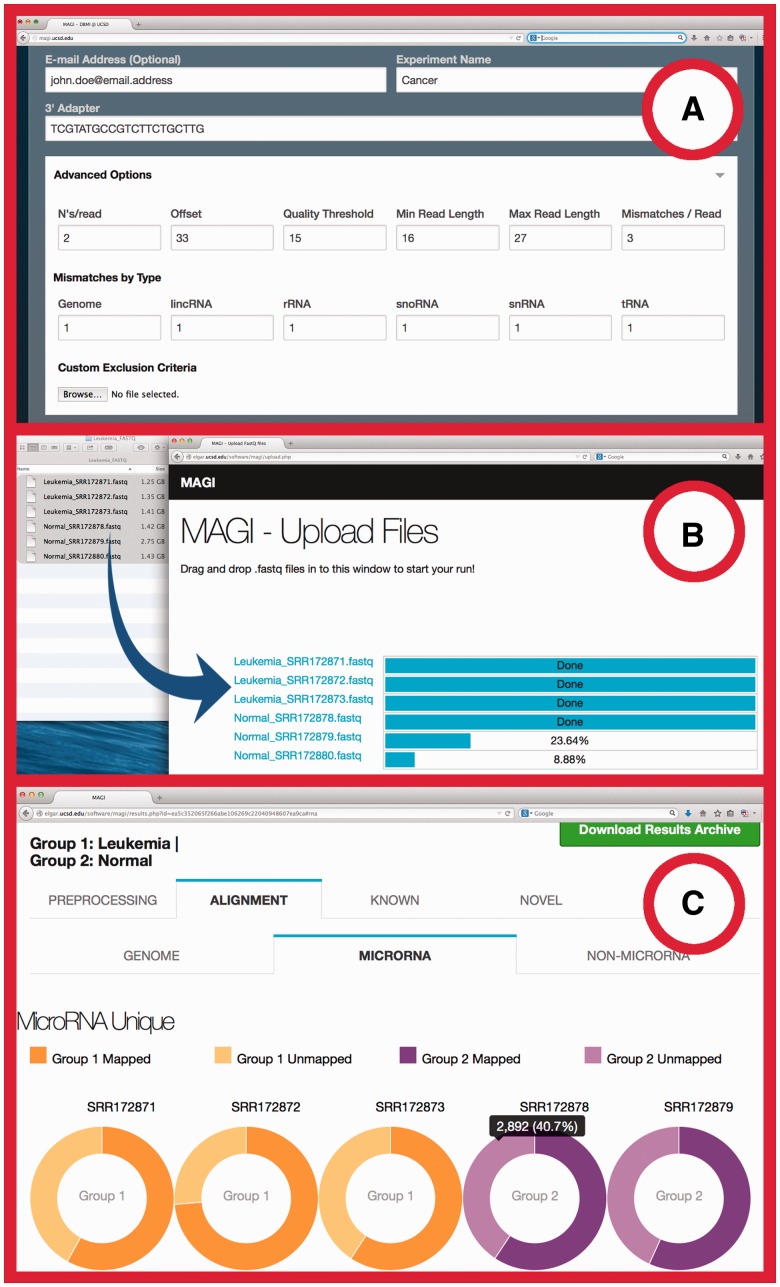

#1—MAGI natively accepts large FASTQ format files as input, requiring no additional file processing by the user. For instance, in Figure 1, with a simple drag and drop into the browser, six FASTQ files are added to the processing queue using HTML5 WebWorkers that scan over the short reads and compress each sequence from a 3GB FASTQ file down to a 3 MB read-count hash-table file, completely within the browser. This process makes the processed data small enough to reach our server in just a few seconds. The adoption of WebWorkers technology reduced the end-to-end analysis time of 24 microRNA-Seq samples (total size 48 GB) down to 4 h using a 2012 MacBook Air with 1.3 GHz dual core CPU, 4 GB RAM, 500 GB HDD. Comparatively, when using omiRas, the FASTQ input file transfer time alone took 5 h. miRAnalyzer and miRTools require file preprocessing that alone took 5–7 h before uploading them to the web service.

Fig. 1.

Screen shot of MAGI (A) Web input form (B) FASTQ file drag-and-drop and data transfer by WebWorkers. (C) D3-enabled interactive charts in a web-report

#2—MAGI uses our parallel implementation of miRanda (Enright et al., 2003), a widely used CPU algorithm for miRNA target identification. Its Compute Unified Device Architecture C implementation (Wang et al., 2014) modifies and parallelizes the Smith–Waterman algorithm to return multiple alignment results with the corresponding trace-back sequences plus heuristic rules for miRNAs. Four NVIDIA M2090 GPU devices (6 GB memory) are installed in our MAGI server and reduced the prediction time from hours using just the CPU to a few minutes using the GPU devices additionally.

#3—MAGI predicts novel miRs using a novel feature-extraction algorithm and random forest-based classifier in just minutes (Stepanowsky et al., 2012). With miRDeep2 (Friedlander et al., 2008), a widely used novel miR prediction algorithm, the prediction module alone took 12–16 h with the same 24 samples. Then, a list of differentially expressed miRNAs between two groups is tabulated using the DESeq (Anders and Huber, 2010) R package that performs a statistical test for both known and novel miRNAs with multiple samples. For quality control, MAGI’s web-socket module collects diagnostic statistics and plots such as average quality score, length distribution of trimmed reads and Guanine-Cytosine contents at the time of FASTQ file drag and drop by a user.

#4—MAGI generates D3 and jQuery-enabled charts where users can zoom in/out, mouse over for actual numbers and export them as separate image files. Tables and pile-up charts are interactive as users can sort and filter with different cutoff values. Such powerful visualization features enable users to discover signals and patterns.

Funding: This work was supported by NIH Grant U54HL 108460. NIH Grant U54HL108460.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- Anders S, Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R106. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enright AJ, et al. MicroRNA targets in Drosophila. Genome Biol. 2003;5:R1. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-5-1-r1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedlander MR, et al. Discovering microRNAs from deep sequencing data using miRDeep. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008;26:407–415. doi: 10.1038/nbt1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackenberg M, et al. miRanalyzer: an update on the detection and analysis of microRNAs in high-throughput sequencing experiments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:W132–W138. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang PJ, et al. DSAP: deep-sequencing small RNA analysis pipeline. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W385–W391. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller S, et al. omiRas: a Web server for differential expression analysis of miRNAs derived from small RNA-Seq data. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:2651–2652. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu C, et al. Differential expression of miR-145 in children with Kawasaki disease. PloS One. 2013;8:e58159. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepanowsky P, Kim J, Ohno-Machado L. A robust feature selection method for novel pre-microRNA identification using a combination of nucleotide-structure triplets. 2012 In Healthcare Informatics, Imaging and Systems Biology (HISB), 2012 IEEE Second International Conference on Healthcare Informatics, Imaging and Systems Biology, La Jolla, CA, USA. IEEE, p. 61. [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, et al. GAMUT: GPU accelerated MicroRNA analysis to uncover target genes through CUDA-miRanda. BMC Med. Genomics. 2014;7(Suppl. 1):S9. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-7-S1-S9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, et al. CPSS: a computational platform for the analysis of small RNA deep sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1925–1927. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W, et al. wapRNA: a web-based application for the processing of RNA sequences. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:3076–3077. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu E, et al. mirTools: microRNA profiling and discovery based on high-throughput sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W392–W397. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.