Synopsis

Cancer vaccines were one of the earliest forms of immunotherapy to be investigated. Past attempts to vaccinate against cancer, including melanoma, have mixed results, revealing the complexity of what was thought to be a simple concept. However, several recent successes and the combination of improved knowledge of tumor immunology and the advent of new immunomodulators make vaccination a promising strategy for the future.

Keywords: Melanoma, Vaccine, Immunomodulator, Adjuvant, Immunotherapy

Introduction

Vaccination is the earliest form of immunotherapy, corresponding to the discovery of the immune system itself, and infectious disease vaccinations are perhaps the greatest advance in the history of medicine. Vaccination for cancer has been much more difficult, although it had very auspicious and early beginnings. The first attempt predates our knowledge of the specific mechanisms involved in vaccination. In the late 19th century William B. Coley, a surgeon in New York at the time, was deeply saddened by the death of a 17 year old patient with metastatic Ewing’s sarcoma, spurring him to begin to look for novel therapies to treat cancer. 1,2 He was struck by the case of a patient who had tumor regression after developing erysipelas.3 He wondered if this phenomenon was due to the infection and, then and took it upon himself to begin inoculating patients with streptococcal organisms in 1891. He reported tumor regression in numerous patients. Coley continued to refine his therapy by using a heat-killed Streptococcus and Serratia combination which became known as Coley’s toxin.1 This administration of an immune adjuvant to the site of a superficial tumor is perhaps the first example of cancer vaccination, albeit using the existing tumor as antigen source. This strategy has interesting echoes in melanoma immunotherapy today, as is discussed below.

More than a century later, Coley’s vision of therapeutic immunology is a reality with the approval of several immune agents in melanoma, and additional promising therapies moving through the development pipeline. Vaccines, however, continue to have a difficult time demonstrating consistent benefit. While several negative vaccine trials have led many to discount the possibility of effective cancer vaccination, there are hopeful signs that continued research efforts are not only justified, but important components of the overall effort to develop effective therapies for melanoma and other cancers. After several decades of failed attempts at developing potent therapeutic vaccines, the first proof-of-concept cancer vaccine Sipeucel-T was approved for use in prostate cancer patients by the FDA in 2010, 4, 5 and as discussed below a trial of peptide vaccination in melanoma showed a significant survival advantage in the vaccine group.6

Increased knowledge of the immune system and its interaction with tumors along with a widening array of clinically available immunomodulators make the prospect of effective vaccines increasingly likely. Over several decades, breakthroughs in basic science and an increased knowledge about the role of antibodies in infection made many surmise that vaccination and the establishment of antitumor antibodies may be a possible strategy to cure cancer. 7 Many cancers have been studied extensively with respect to vaccine treatment but, perhaps, no cancer as extensively as melanoma.

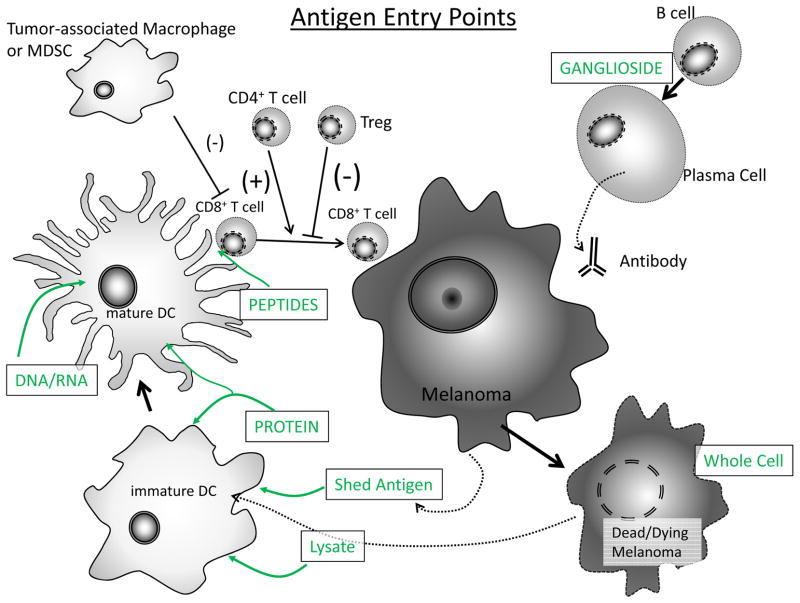

Vaccine strategies are highly varied and may be characterized by the antigen source and the adjuvants and/or immune modulators given with the antigen. Much of the early period of vaccine development was characterized by substantial debate regarding the ideal antigen. Options vary from the simplest peptide vaccines to the most complex autologous whole-tumor cells. Each approach has advantages and disadvantages. (Table 1, Figure 1) Generally, simple peptide vaccines are easier to prepare, store, administer and monitor, but they offer the narrowest spectrum of tumor targets and are potentially relevant to fewer patients. More complex vaccines are the most likely to offer antigens that are relevant to any given patient, but are much more difficult to produce and administer. They also present substantial difficulties in monitoring immune responses since those responses may be extremely varied among different individuals. It is now becoming increasingly apparent that the nature of the antigen is only a part of the story, perhaps a small part. What may be more significant is the context of the immune stimulation in terms of both patient characteristics and immunologic adjuvants or other immunomodulators. Modification of these factors could prove much more important than the specific source of antigen for a vaccine.

Table 1.

Antigen Types

| Antigen Type | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| peptide | Easy preparation Easy storage Simple monitoring |

Narrow antigen spectrum HLA restriction Many limited to Class I presentation |

| protein | No HLA restriction Relatively simple preparation |

Requires antigen cross-presentation to sensitize CD8 T cells Still fairly narrow antigen spectrum |

| DNA/RNA | Relatively simple preparation No HLA restriction |

May be difficult to generate both CD4 and CD8 responses Requires delivery of genetic material |

| ganglioside | Immune monitoring (antibody response) is relatively simple | Relies largely on humeral response for effect |

| lysate | Broad antigen spectrum | Preparation/storage more difficult |

| whole cell | Most diverse antigen spectrum | Preparation/storage most difficult |

Figure 1.

Antigen Entry Points: Numerous options exist for vaccine antigen and each may enter at a different point in immune response development. Peptides, the simplest antigen, enter at the immunologic synapse between T-cell and antigen presenting cell and require not processing. Others require uptake, processing and presentation to be recognized. Antigen may also be released from dead or dying cancer cells, either injected as a prepared vaccine or produced from existing metastases.

Autologous Melanoma Vaccines

In autologous vaccines, the patient’s own tumor is used as the antigen source. There are several significant advantages to autologous vaccines. First, since the source of antigen is the patient’s own tumor, there is, by definition, a HLA-type match ensuring that antigen presentation is adequate. Second, they are likely to contain antigens that are unique to that particular patient and, thus, are personalized. However, the derivation of vaccine from an autologous source is daunting from a practical standpoint, and there is little consensus about the optimal method. In addition, sufficient tumor must be available in order to provide raw material for the vaccine. Thus, patients who have low tumor burden or those who have undergone complete resection of their disease are not candidates for this type of therapy. Finally melanoma metastases may be genetically and antigenically heterogeneous within any given patient.8 This could create a situation in which a single metastases, used for vaccine preparation, would not contain enough antigenic diversity to lead to a protective response against every metastatic focus.

An early autologous vaccine to undergo phase 3 trial was of a heat shock protein gp96 peptide complex (HSPPC-96) vaccine derived from autologous tumor.9,10 Heat shock proteins are soluble, intracellular “sticky” proteins and bind peptides including antigenic peptides generated within cells. They are thought to play an important role as chaperones for antigen presentation, required for instructing the antigen-specific antitumor immune responses. When heat shock proteins are purified from tumors, non-covalent complexes of these proteins along with peptides expressed by the tumor cell are obtained. When injected into the skin, heat shock proteins may interact with antigen presenting cells through CD91, a heat shock protein receptor. This leads to re-presentation of heat shock protein-chaperoned peptides by Major Histocompatibility (MHC) proteins as well as stimulation and maturation of antigen presenting cells. Despite their extracellular location upon administration, the tumor-associated peptides bound to gp96 may gain access to presentation on MHC class I (cross-priming), important for activation of antitumor killer T cell responses.

The phase 3 trial studied in 322 patients at 71 centers, and randomly assigned subjects 2:1 to receive either the vaccine or physician choice of dacarbazine, temozolomide, interleukin-2 (IL-2), or complete tumor resection.10 There was no difference in overall survival, although patients with M1a or M1b disease who received more than 10 doeses vaccine survived longer than those receiving fewer treatments. While this type of analysis may be biased, the authors here attempted to control for such bias using “landmark” analysis. In addition, pre-clinical models suggested that at least 4 doses of the vaccine would be required to stimulate a protective immune response. The authors concluded that this M1a and M1b subset of patients may be candidates for further study, and this vaccination strategy remains an area of interest.11 However, there is also a theoretical concern that chronic stimulation with antigen may lead to tolerance, rather than effective immunity and the ideal duration of cancer vaccination in patients remains unclear. Othy Elsevier er whole-cell autologous vaccines include those developed by Berd and colleagues, subsequently evaluated in clinical trials as M-Vax. 12 This vaccine uses the patients’ irradiated melanoma cells, which are modified with dinitrophenyl, a hapten, which previous research suggests helps improve antigen visibility.13 The treatment program consists of multiple intradermal injections of DNP-modified autologous tumor cells mixed with bacille Calmette-Guerin as an immunological adjuvant. Administration of DNP vaccine to patients with metastatic melanoma induces the development of inflammation in metastases. 14 In a phase 3 trial, which has completed accrual, patients were assigned to M-Vax or placebo followed by low-dose IL-2. Primary endpoints are best overall tumor response and survival at 2 years. The trial was suspended in 2009, and results have yet to be published. Another autologous, whole-cell strategy was developed by Dillman and colleagues and consists of resected tumor cells which are cultured in vitro and irradiated prior to administration.15 This vaccine has not been evaluated in phase 3 studies. (Table 2)

Table 2.

Phase 3 trials of melanoma vaccines

| Author | year | n | Arms | HR | CI | p-value | Notes: |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kirkwood | 2001 | 880 | HD-IFN vs GM-2KLH/QS-21 | RFS: 1.47 OS: 1.52 |

(1.14–1.90) (1.07–2.15) |

0.0015 0.009 |

|

| Hersey | 2002 | 700 | VMCL vs. Obs | RFS: 0.86 OS: 0.81 |

(0.7–1.07) (0.64–1.02) |

0.17 0.068 |

|

| Sondak | 2002 | 698 | Melacine vs. Observation | 0.84 (rec or death) | (0.66–1.08) | 0.17 | HLA-A2+, C3+ significant |

| Schadendorf | 2006 | 108 | DC+ peptides vs. DTIC | OS | 0.48 | AWD Stage IV | |

| Morton | 2007 | 1160 | Canvaxin vs. Placebo | 1.26 | 0.040 | Stage III | |

| Morton | 2007 | 496 | Canvaxin vs. Placebo | 1.29 | (0.97–1.72) | 0.086 | Stage IV |

| Testori | 2008 | 322 | hsp96 vaccine vs. BAC | 0.316 | Stage IV | ||

| Hodi | 2010 | 676 | ipilimumab vs. peptide vs. both | OS: 1.04 | 0.76 | AWD | |

| Lawson | 2010 | 398 | GM-CSF +/− peptides | OS: 0.94 DFS: 0.93 |

(0.70–1.26) (0.73–1.27) |

0.670 0.709 |

|

| Schwartzentruber | 2011 | 185 | IL-2 +/− peptides | RR: PFS: OS: |

0.03 0.008 0.06 |

AWD, all favor vaccine | |

| Eggermont | 2013 | 1314 | GM2-KLH/QS-21 vs Observation | RFS: 1.03 OS: 1.66 |

(0.84–1.25) (0.90–1.51) |

0.81 0.25 |

|

| Suriano | 2013 | 250 | VMO vs. Vaccinia | OS | 0.70 | ||

| Unpublished | 2013 | ? | MAGE-A3 vs. placebo | OS | NS | subgroups pending |

An alternative to whole-cell autologous vaccines is the use of tumor lysates pulsed onto dendritic cells. Dendritic cells (DCs) are specialized leukocytes that are the most potent generators of de novo antigen-specific immune responses. While several immune cells are capable of presenting antigens to activate effector cells, the use of dendritic cells as an immune adjuvant for tumor vaccination may provide a more potent source of immune activation. Indeed, a randomized phase II comparison of autologous tumor antigen-pulsed dendritic cells versus autologous whole cell vaccination showed a survival advantage in the dendritic cell arm (HR 0.27, 95% CI 0.098–0.729).16 Additional considerations of dendritic cell vaccines are considered below.

Allogeneic Vaccines

The use of vaccines derived from stock melanoma cell lines has several theoretical advantages over autologous vaccines. First, the vaccine may be prepared in advance of a patient’s need for treatment, eliminating the delay in therapy required when deriving cells from resected tumors. Second, the cells used in the vaccine can be pre-selected for high antigen expression. Third, the presence of foreign, allo-antigens could stimulate a more potent immune response than that engendered by autologous tumor. Several allogeneic whole cell or whole cell lysate vaccines have been evaluated in Phase 3 clinical trials including those using vaccinia melanoma cell lysate (VMCL), vaccinia melanoma oncolysate (VMO), Melacine, and Canvaxin.

The VMCL vaccine employs a single melanoma cell line, which is lysed in vitro using vaccinia virus and injected intradermally. Infection of melanoma cells with vaccinia virus could provide additional stimulation of antitumor immunity by introducing viral pattern recognition ligands in the vaccine. The Phase 3 trial included 700 patients in Australia and was randomized 1:1 against observation as control.17 Data were analyzed with a median of 8 years of follow up and demonstrated a non-significantly increased overall survival in the vaccine group (5-year OS 60.6% vaccine vs. 54.8% control, HR 0.81, 95% CI 0.64–1.02, p=0.068). Notably, the patients in the control arm also showed longer survival compared to that expected for the time, a seemingly common phenomenon in melanoma vaccine trials.

The next large trial of a whole-cell lysate was the VMO vaccine. This consisted of a lysate of four melanoma cell lines and a trial of 250 patients from 11 North American institutions who were randomized to vaccine or vaccinia only. A study of the long-term results of the trial was published in 2013 and demonstrated no indication of benefit (or harm) for the vaccine group.18

A third Phase 3 trial was conducted the Southwest Oncology Group and evaluated Melacine, a lysate of two melanoma cell lines combined with a detoxified Freund’s adjuvant (DETOX).19 Freund’s adjuvant is comprised of mycobacterial components which are potent immune stimulators. The study enrolled 689 subjects who were randomized to vaccine or to observation. The study showed a hazard ratio of 0.84 in favor of the vaccine arm, but the difference was not statistically significant. However, examination of subgroups with cross reactivity with the HLA types presented in the vaccine, particularly HLA-A2 and HLA-C3 positive subjects, showed a significant advantage.20 It is interesting to speculate that if allogeneic tumor cells were to be employed for further tumor vaccine development, perhaps some level of matching to the recipient’s MHC could improve the efficacy of the vaccine. Melacine was approved for use in Canada for Stage IV melanoma, based upon improved quality of life compared to combination chemotherapy. It was not approved in the United States or elsewhere.

The largest Phase 3 clinical experience for an allogeneic whole cell vaccine is with Canvaxin.21 Canvaxin consists of 3 melanoma cell lines, selected for their spectrum of antigen expression and irradiated at doses so that the cells would be live but replication incompetent upon administration. The vaccine showed excellent results in Phase 2 trials and was evaluated in two large, randomized trials in resected Stage III and Stage IV melanoma. Subjects were randomized to vaccine or placebo with both arms receiving bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) as an immune adjuvant with the first two doses. The trial in Stage III patients enrolled 1,160 subjects, and the Stage IV study enrolled 496.22 Both trials were halted after interim analyses for futility as there was no significant difference from placebo.

Interestingly again, the Canvaxin studies demonstrated outcomes in the vaccine arms that were very similar to those predicted by Phase 2 results.23 These vaccine survival times, which were superior to historical controls and appeared better than those of other contemporary adjuvant therapy trials, were no better than those of the control group who only received BCG. While BCG had been evaluated as an immune adjuvant in melanoma before, prior trials used relatively ineffective administration schemes and were inadequately powered to evaluate the therapy. It has also been noted that survival times of the control arms of the study were longer than the vaccine arm, though these values were not technically statistically different at the threshold of an interim analysis (Stage III p=0.040, Stage IV p=0.086). It is possible that this vaccine strategy and others could be improved with optimization of dosing and schedule since chronic, repeated inoculation with tumor antigens may lead to less robust antitumor responses and instead induce tolerance to tumor antigens. However, the overall survival of all subjects both in the treated and control arms was longer than expected indicating participation in the protocol was not harmful.

Ganglioside Vaccines

Gangliosides are glycolipids that are differentially expressed in several cancer types. Thus, they are also potential targets as tumor-specific antigens for immune therapy and/or vaccination.24 Two large Phase 3 trials have been performed using the GM2 ganglioside. The first of these was conducted by the Easter Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) in collaboration with the North American cooperative groups.25 This study compared GM2 vaccine (consisting of the ganglioside coupled to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) and the QS-21 adjuvant) to high-dose interferon-α2b. The trial enrolled 880 patients and demonstrated superior relapse-free and overall survival in the interferon arm.

The second trial was performed by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) and randomized subjects to either GM2-KLH-QS21 vaccine or observation.26 The trial included 1314 subjects and was halted at the second interim analysis for futility as early follow up showed no suggestion of a relapse-free survival advantage to the vaccine group and a possible overall survival disadvantage. With additional follow up, the survival curves are almost overlapping; indicating that while there was no harm by vaccination, there was clearly no benefit.

Peptide Vaccines

Peptides are perhaps the most commonly used tumor-associated antigen (TAA) source for melanoma vaccines. These protein fragments are normally presented in the context of Major Histocompatibility (MHC) proteins to be recognized by T-lymphocytes. Cancer-specific peptides were identified in melanoma over two decades ago. 27, 28 The peptides are easily produced, stored and administered. Because of the narrow spectrum of immune responses possible to the peptides, immunological monitoring of peptide vaccination is relatively straightforward. In part as a result of these advantages, several dozen peptide vaccine trials have been performed in melanoma including three randomized Phase 3 trials.6, 29, 30

However, the simplicity of these antigens is also a potential weakness. Each peptide generally contains only one epitope for the immune system to target, and peptides are limited in compatibility to HLA-matched patients. Since HLA-A2 is a relatively common allele in melanoma patients, most peptide vaccine studies conducted to date have been limited to peptides which bind HLA-A2 and therefore have only been available to HLA-A2+ patients. In addition, with a narrow spectrum of target epitopes, the potential for antigen loss through immune selection and survival of antigen-negative clones is a concern. With identification of numerous potential peptide antigens with histocompatibility for several HLA types, some of this limitation has been at least partially overcome.31 It is still not clear whether those improvements will translate into increased effectiveness in the clinical setting. Despite the relative ease of peripheral blood monitoring of immunization, correlations of successful immunization by such monitoring and clinical outcomes have been limited or even inverse (i.e. lower peripheral blood responses in clinical responders).32, 33 It is also quite possible that the in vitro assays used thus far to monitor peripheral blood responses lack the relevant immune readouts that correlate to clinical benefit.

The results of three Phase 3 trials of peptide vaccination have been mixed. All three trials included a systemic immunomodulating drug and examined the effect of adding peptide vaccines. One examined high-dose interleukin-2, an approved therapy for metastatic melanoma, with or without gp100 peptide and incomplete Freund’s adjuvant in patients with measurable metastatic disease. 6 The multicenter trial enrolled 185 subjects and demonstrated a significant improvement in the overall response rate (16% vs 6%, p=0.03) and progression free survival (2.2 vs 1.6 months, p=0.008) in the vaccine group. The trend in median overall survival was improved in the gp100 group compared to the IL-2 alone group, but was not quite statistically significant (17.8 vs 11.1 months, p=0.06). Thus, this is the first peptide vaccine to show a clinical benefit in a phase 3 trial.

Another trial examined the role of both a peptide vaccine and GM-CSF as adjuvant therapies in patients with resected Stage III and IV melanoma. This trial enrolled 815 patients who were assigned to one of the multiple arms of the trial depending on their HLA-A2 status. Only HLA-A2+ patients (n=398) were randomized to receive vaccine or peptide placebo. 30 The study has only been reported in abstract form, and mature results are expected sometime this year. Preliminary results reported a relapse free survival advantage with GM-CSF, but this finding has lost statistical significance over time and was not accompanied by an overall survival benefit. The addition of peptide vaccination did not appear to improve overall or relapse-free survival.

The third Phase 3 trial involving peptide vaccination was conducted within a larger trial evaluating the efficacy of CTLA-4 blockade with ipilimumab.29 The trial had three arms: gp100 peptide alone (n=136), ipilimumab alone (n-137) and the combination (n=403). The trial showed a significant survival advantage to ipilimumab but no advantage to peptide vaccination. This study provides an interesting contrast to the trial of peptide vaccination in the context of interleukin-2, which did show a benefit, and highlights the paramount importance of context to determine the clinical impact of an immune therapy. The mixed results of these three peptide vaccine trials indicate much additional work is required to optimize vaccine strategies employing peptides.

Immune adjuvants and immunomodulators

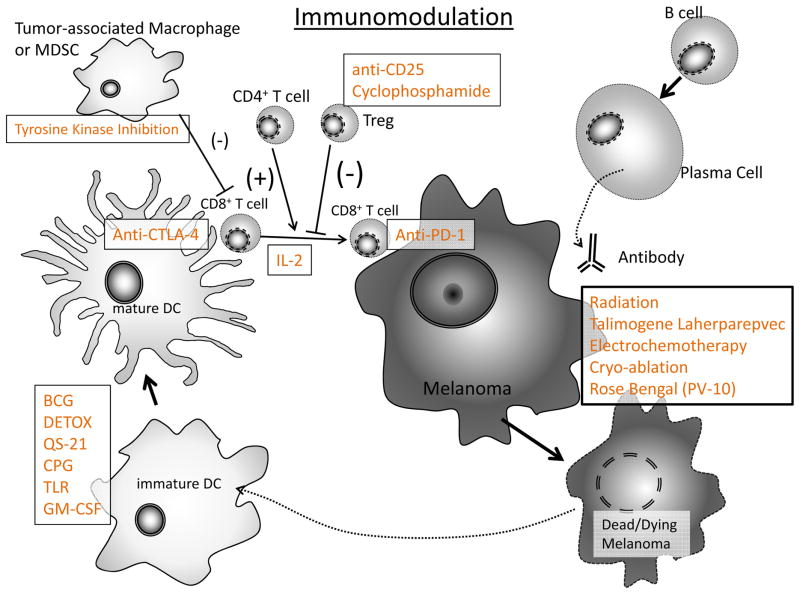

Although our review to this point has been focused on the types of antigen sources that have been used in melanoma vaccines; an equally important, if not more important, consideration may be the context of immunization with regard to the patient population, the frequency of dosing, and the immune adjuvant and immunomodulators that are given with the vaccine. As our knowledge of the immune system and its interaction with melanoma has improved, new opportunities for rational immunization improvement have arisen. (Figure 2)

Figure 2.

Immunomodulation: The spectrum of available agents to boost or modify immune responses has increased dramatically in recent years and can interact with the system in numerous places.

Vaccines, including many infectious disease vaccines, are given with non-specific immune adjuvants to boost immunologic responses. Vaccine adjuvants serve to increase recognition of antigens, amplify immune responses, and modulate those responses. Many early trials used traditional vaccine adjuvants, such as incomplete Freund’s, while other used live or killed microorganism components such as BCG 21 or detoxified mycobacterial cell walls (e.g. DETOX). 19 The discovery of toll-like receptors and elucidation of their importance in the development of immune responses has led to their ligands being incorporated into some vaccination strategies.

One of the most promising areas of enhancing vaccine responsiveness is the use of dendritic cells (DC) as immune adjuvants.34 These cells are primarily responsible for generation of new responses in vivo. Dendritic cells may be obtained from bone marrow, but now for clinical trials are most commonly derived from peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Early studies of DC vaccines showed very encouraging response rates among relatively advanced melanoma patients. Nestle et al. utilized autologous dendritic cells cultured in GM-CSF and interleukin-4 and then pulsed with tumor lysates or peptides before infusion into 16 patients with advanced melanoma. 35 Two out of 16 patients had a complete response (CR) while 3 out of 16 patients had a partial response (PR). More recently a DC vaccine was evaluated in a Phase 3 trial of 108 subjects.36 The DC in this trial were pulsed with peptides and the control arm was treated with dacarbazine chemotherapy. There was no indication of benefit to vaccination, and the trial was closed at the recommendation of the Data Safety Monitoring Board.

It has now become clear, however, that not all DC are the same. In fact, depending on the state of maturation of the DC, and the cytokines and chemokines they produce, the cells may not traffic well to present antigen, and may actually skew immune responses toward tolerance. This new knowledge is being incorporated into the design of current DC vaccine trials in melanoma and other cancers. 37

In a recent pilot trial, dendritic cells were grown with GM-CSF, interleukin-4, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and CD40 ligand (CD40L). 38 Both TNF and CD40L are important for maturation of dendritic cells. The DC were then pulsed with allogeneic, killed melanoma cells. Of 20 advanced melanoma patients vaccinated, 1 showed a CR while another patient had a PR. This study was proof of concept that HLA restriction could be overcome by loading mature dendritic cells with allogeneic killed melanoma cells.

Additional DC vaccine trials are planned, including two upcoming phase 3 trials. There is hope that improved understanding of DC biology will increase the benefits of vaccination for these studies.

Intralesional Immunotherapy: Tumor (in situ) as vaccine

We have characterized Coley’s intralesional injection of bacterial toxins as “vaccination,” although the injection itself did not contain tumor antigens. Rather, the antigens were already present, and he simply added the adjuvant. A very similar strategy was pursued by Morton and colleagues starting in the 1960s using BCG.39 In the first such case, a woman presented with numerous in-transit metastases on her upper extremity. Her other arm had been paralyzed by polio, and so she declined an amputation. Morton, who was in the early stages of developing an allogeneic whole cell vaccine at the time, elected to inject BCG into her melanoma lesions, using the lesion as vaccine. Subsequently, all of her lesions, both injected and non-injected, regressed completely. She remained free of disease for many years thereafter.

BCG was explored with great enthusiasm after early publications of melanoma regression. 40 Subsequent reports documented regression of non-injected metastases, even at visceral sites.41 However, severe toxicities, including disseminated intravascular coagulation, anaphylaxis and death were reported and enthusiasm for the technique waned.42,43 A few centers continue to use BCG in this way, though at greatly reduced doses, and it is included in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines as an option for in-transit disease.44 A recent report used the combination of BCG and imiquimod, the topical toll-like receptor agonist, and demonstrated regression of extensive areas of in-transit metastases with minimal toxicity.45

Although radiation is generally understood to be immunosuppressive, it may also have local immunostimulatory effects such as increased antigen expression and/or release. Local radiation therapy may facilitate development of systemic immunity, something known as the abscopal effect. An example of this was recently reported in the context of a patient previously treated with ipilimumab.46 Although it is difficult to rule out the possibility of a delayed clinical response to checkpoint blockade, numerous similar examples, and biologically promising mechanisms suggest radiation may be a fruitful avenue for further study to stimulate antitumor immune responses. Several clinical trials are currently evaluating local therapies such as radiation or regional chemotherapy administration as adjuncts to systemic immunotherapies.

Another developing local immunotherapy is talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC), an oncolytic herpes simplex virus, which was engineered to express granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. 47 Tumor destruction is thought to stem from both the oncolytic effect of the herpes simplex virus which causes the melanoma cell to lyse and GM-CSF which is expressed upon infection and may attract and activate dendritic cells to present antigens from the tumor lysate inducing an antitumor immune response more systemic immune response. 47–49 Recently, the results of the OPTiM trial, a phase3 randomized control trial comparing T-VEC to GM-CSF alone, was presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 50 Unresectable Stage IIIB/C or Stage IV patients with injectable cutaneous, subcutaneous or nodal lesions were randomized to intralesional T-VEC or subcutaneous GM-CSF. The objective response rate (ORR) with T-VEC was 26% with 11% complete response (CR) compared to GM-CSF alone which had a 6% ORR and 1% CR. Durable response rate for T-VEC was 16% compared to 2% for GM-SCF. Interim overall survival analysis showed a trend in benefit toward T-VEC. Thus, T-VEC is the first such melanoma local immune therapy to show benefit in overall survival in a phase 3 randomized clinical trial in melanoma.

Future

Although many of the clinical trials evaluating melanoma vaccines have not demonstrated a benefit, and some have even raised concerns that vaccination can be harmful, there are many reasons to support that vaccines will be an important component of optimal therapy for melanoma in the future. Successful deployment of melanoma vaccines was probably hampered by the fact that they were the first immune therapies to be developed. Introduction in an era of less sophisticated knowledge of tumor immunology and clinical trial design led to studies conducted with insufficient sample sizes or in populations that could not be accurately stratified due to inadequate staging. Despite these challenges some successes have kept cancer vaccination research alive. Hopeful signs include two positive randomized trials in the peptide/interleukin-2 study 6 and the T-VEC trial 49 as well as the availability of new and increasingly diverse immunomodulators.

Perhaps the most important challenge that faces vaccine development is the identification of reliable surrogates for clinical outcomes. Traditionally clinical development begins with pre-clinical investigations and many early phase trials use surrogates, such as immune endpoints to select therapies to take forward. This model appears to be unreliable in melanoma vaccines. For example, pre-clinical models had suggested a strong synergy between peptide vaccination and checkpoint blockade with anti-CTLA-4 antibody but was not borne out by the completed Phase 3 trial. Numerous immune surrogates have been used to guide modification and combination of immune therapies. One example is that of GM-CSF, which leads to improved antibody responses, but not to improved clinical outcomes in multiple randomized trials. 51 Another is the measurement of number of circulating antigen-specific lymphocytes. In a study performed at the National Cancer Institute, several cytokines were added to peptide vaccines and peripheral blood responses were monitored. The only group with significant clinical responses, that in which peptides were combined with interleukin-2, had decreased numbers of circulating antigen-specific cells.32 Development of other measures of productive anti-tumor responses is needed and may include evaluation of tumor material to assess immune infiltrates or down regulation of immunosuppressive factors. The current wealth of agents that are potentially useful as adjuncts to vaccination are most welcome, but will require improved means of assessment to sort through. Reliance on large randomized trials with survival endpoints will be too slow to provide answers in the time frame many of our patients need.

Coley’s vision of curing cancer through vaccination has become a reality for some patients.4 The advent of new immune agents and new means of applying immunotherapies make the prospect of extending benefits to more patients increasingly likely. We should remember Coley’s pioneering spirit, including the courage and tenacity he needed to inject patients with his toxin as we enter a critical second phase of melanoma vaccine development.

Key Points.

Numerous vaccine antigen sources have been evaluated, and each has advantages and disadvantages.

Most phase 3 vaccine trials to date have not shown clinical benefit, although there have been a few successes and suggestions of activity.

Novel vaccine strategies using the tumor in vivo as an antigen source bypass the need to define tumor antigens; allow simple, yet personalized therapy; and are perhaps the most interesting current method of vaccination.

Numerous immunomodulators are now available or in development that could enhance vaccination.

Adequate immune monitoring with clinically meaningful surrogate endpoints will be critical for additional vaccine development.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by fellowship funding from the William Randolph Hearst Foundations (Los Angeles, CA) (Dr. Fujita), and by funding from John Wayne Cancer Institute Auxiliary (Santa Monica, CA), Dr. Miriam & Sheldon G. Adelson Medical Research Foundation (Boston, MA), the Borstein Family Foundation (Los Angeles, CA) and National Cancer Institute grant P01 CA29605.

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Coley W. The treatment of malignant tumors by repeated inoculations of erysipelas: With a report of ten original cases. New York: Lea Brothers & Co; 1893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coley W. Treatment of inoperable malignant tumors with the toxins of erysipelas and the bacillus prodigiosus. Trans Am Surg Assoc. 1894;12:183. [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCarthy EF. The toxins of William B. Coley and the treatment of bone and soft-tissue sarcomas. Iowa Orthop J. 2006;26:154–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kantoff PW, Higano CS, Shore ND, et al. Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(5):411–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheever MA, Higano CS. PROVENGE (Sipuleucel-T) in prostate cancer: the first FDA-approved therapeutic cancer vaccine. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(11):3520–6. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-3126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwartzentruber DJ, Lawson DH, Richards JM, et al. gp100 peptide vaccine and interleukin-2 in patients with advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(22):2119–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1012863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwartz RS. Paul Ehrlich’s magic bullets. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(11):1079–80. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harbst K, Lauss M, Cirenajwis H, et al. Molecular and genetic diversity in the metastatic process of melanoma. J Pathol. 2014 doi: 10.1002/path.4318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tosti G, di Pietro A, Ferrucci PF, et al. HSPPC-96 vaccine in metastatic melanoma patients: from the state of the art to a possible future. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2009;8(11):1513–26. doi: 10.1586/erv.09.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Testori A, Richards J, Whitman E, et al. Phase III comparison of vitespen, an autologous tumor-derived heat shock protein gp96 peptide complex vaccine, with physician’s choice of treatment for stage IV melanoma: the C-100-21 Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(6):955–62. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.9941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tosti G, Cocorocchio E, Pennacchioli E, et al. Heat-shock proteins-based immunotherapy for advanced melanoma in the era of target therapies and immunomodulating agents. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2014 doi: 10.1517/14712598.2014.902928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berd D, Sato T, Maguire H, et al. Immunopharmacologic analysis of an autologous, hapten-modified human melanoma vaccine. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(3):403–15. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berd D. M-Vax: an autologous, hapten-modified vaccine for human cancer. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2002;2(3):335–42. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2.3.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berd D. M-Vax: an autologous, hapten-modified vaccine for human cancer. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2004;3(5):521–7. doi: 10.1586/14760584.3.5.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dillman RO, Nayak SK, Barth NM, et al. Clinical experience with autologous tumor cell lines for patient-specific vaccine therapy in metastatic melanoma. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 1998;13(3):165–76. doi: 10.1089/cbr.1998.13.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dillman R, Selvan S, Schiltz P, et al. Phase I/II trial of melanoma patient-specific vaccine of proliferating autologous tumor cells, dendritic cells, and GM-CSF: planned interim analysis. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2004;19(5):658–65. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2004.19.658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hersey P, Coates A, McCarthy W, et al. Adjuvant immunotherapy of patients with high-risk melanoma using vaccinia viral lysates of melanoma: results of a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4148–4190. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.12.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suriano R, Rajoria S, George AL, et al. Follow-up analysis of a randomized phase III immunotherapeutic clinical trial on melanoma. Mol Clin Oncol. 2013;1(3):466–472. doi: 10.3892/mco.2013.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sondak V, Liu P, Tuthill R, et al. Adjuvant immunotherapy or resected, intermediate-thickness, node-negative melanoma with an allogeneic tumor vaccine: overall results of a randomized trial of the Southwest Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2058–2066. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sosman J, Unger J, Liu P, et al. Adjuvant immunotherapy of resected, intermediate-thickness, node-negative melanoma with an allogeneic tumor vaccine: Impact of HLA class I antigen epression on outcome. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(8):2067–2075. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morton D, Hsueh E, Essner R, et al. Prolonged survival in patients receiving active immunotherapy with Canvaxin therapeutic vaccine after complete resection of melanoma metastatic to regional lymph nodes. Ann Surg. 2002;236(4):438–48. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200210000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morton DL, Mozzillo N, Thompson JF, et al. An international, randomized, phase III trial of bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) plus allogeneic melanoma vaccine (MCV) or placebo after compete resection of melanoma metastatic to regional or distant sites. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(18S):Abstract 8508. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morton D, Mozzillo N, Thompson J, et al. An international, randomized, double-blind, phase 3 study of the specific active immunotherapy agent, Onamelatucel-L (Canvaxin), compared to placebo as post-surgical adjuvant in AJCC stage IV melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13(2 Suppl):5s. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morton D, Ravindranath M, Irie R. Tumor gangliosides as targets for active specific immunotherapies of melanoma in man. In: Svennerholm L, Asbury A, Reisfeld R, et al., editors. Progress in Brain Research. Vol. 104. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1994. pp. 251–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirkwood J, Ibrahim J, Sosman J, et al. High-dose interferon alpha 2b significantly prolongs relapse-free and overall survival compared with the GM2-KLH/QS-21 vaccine patients with resected stage IIB-III melanoma: results of intergoup trial E1694/S9512/C509801. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2370. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.9.2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eggermont AM, Suciu S, Rutkowski P, et al. Adjuvant ganglioside GM2-KLH/QS-21 vaccination versus observation after resection of primary tumor > 1. 5 mm in patients with stage II melanoma: results of the EORTC 18961 randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(30):3831–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.9303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van der Bruggen P, Traversari C, Chomez P, et al. A gene encoding an antigen recognized by cytolytic T lymphocytes on a human melanoma. Science. 1991;254(5038):1643–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1840703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenberg S, Yang J, Schwartzentruber D, et al. Immunologic and therapeutic evaluation of a synthetic peptide vaccine for the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma. Nat Med. 1998;4(3):321–7. doi: 10.1038/nm0398-321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. The New England journal of medicine. 2010;363(8):711–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lawson DH, Lee SJ, Tarhini AA, et al. E4697: Phase III cooperative group study of yeast-derived granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) versus placebo as adjuvant treatment of patients with completely resected stage III–IV melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(15s):Abstract 8504. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Slingluff CL, Jr, Petroni GR, Chianese-Bullock KA, et al. Randomized multicenter trial of the effects of melanoma-associated helper peptides and cyclophosphamide on the immunogenicity of a multipeptide melanoma vaccine. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(21):2924–32. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.8053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosenberg S, Yang J, Schwartzentruber D, et al. Impact of cytokine administration on the generation of antitumor reactivity in patients with metastatic melanoma receiving a peptide vaccine. J Immunol. 1999;163:1690–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Slingluff CL., Jr The present and future of peptide vaccines for cancer: single or multiple, long or short, alone or in combination? Cancer J. 2011;17(5):343–50. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e318233e5b2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Faries MB, Czerniecki BJ. Dendritic cells in melanoma immunotherapy. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2005;6(3):175–84. doi: 10.1007/s11864-005-0001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nestle F, Alijagic S, Gilliet M, et al. Vaccination of melanoma patients with peptide or tumor lysate-pulsed dendritic cells. Nat Med. 1998;4(3):269–70. doi: 10.1038/nm0398-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schadendorf D, Nestle F, Broecker E, et al. Dacarbacine (DTIC) versus vaccination with autologous peptide-pulsed dendritic cells as first-line treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma: Results of a prospective-randomized phase III study. In: Grunberg SM, editor. Am Soc of Clin Oncol. Vol. 23. New Orleans, LA: Am Soc of Clin Oncol; 2004. p. 709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou F, Ciric B, Zhang GX, et al. Immune tolerance induced by intravenous transfer of immature dendritic cells via up-regulating numbers of suppressive IL-10(+) IFNgamma(+)- producing CD4(+) T cells. Immunol Res. 2013;56(1):1–8. doi: 10.1007/s12026-012-8382-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Palucka AK, Ueno H, Connolly J, et al. Dendritic cells loaded with killed allogeneic melanoma cells can induce objective clinical responses and MART-1 specific CD8+ T-cell immunity. J Immunother. 2006;29(5):545–57. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000211309.90621.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morton D, Eilber F, Holmes E, et al. BCG immunotherapy of malignant melanoma: summary of a seven-year experience. Ann Surg. 1974;180(4):635–43. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197410000-00029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sopkova B, Kolar V. Intralesional BCG application in malignant melanoma. Neoplasma. 1976;23(4):421–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mastrangelo M, Bellet R, Berkelhammer J, et al. Regression of pulmonary metastatic disease associated with intralesional BCG therapy of intracutaneous melanoma metastases. Cancer. 1975;36(4):1305–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197510)36:4<1305::aid-cncr2820360417>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McKhann CF, Hendrickson CG, Spitler LE, et al. Immunotherapy of melanoma with BCG: two fatalities following intralesional injection. Cancer. 1975;35(2):514–20. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197502)35:2<514::aid-cncr2820350233>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sparks F, Silverstein M, Hunt J, et al. Complications of BCG immunotherapy in patients with cancer. N Engl J Med. 1973;289:827–830. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197310182891603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coit DG, Andtbacka R, Anker CJ, et al. Melanoma, version 2.2013: featured updates to the NCCN guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 11(4):395–407. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kidner TB, Morton DL, Lee DJ, et al. Combined intralesional Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) and topical imiquimod for in-transit melanoma. J Immunother. 2012;35(9):716–20. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e31827457bd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hiniker SM, Chen DS, Knox SJ. Abscopal effect in a patient with melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(21):2035. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1203984. author reply 2035–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaufman HL, Bines SD. OPTIM trial: a Phase III trial of an oncolytic herpes virus encoding GM-CSF for unresectable stage III or IV melanoma. Future Oncol. 2010;6(6):941–9. doi: 10.2217/fon.10.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Senzer NN, Kaufman HL, Amatruda T, et al. Phase II clinical trial of a granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-encoding, second-generation oncolytic herpesvirus in patients with unresectable metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(34):5763–71. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.3675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kaufman HL, Kim DW, DeRaffele G, et al. Local and distant immunity induced by intralesional vaccination with an oncolytic herpes virus encoding GM-CSF in patients with stage IIIc and IV melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;17(3):718–30. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0809-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Andtbacka R, Collichio FA, Amatruda T, et al. OPTiM: A randomized phase III trial of talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC) versus subcutaneous (SC) granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) for the treatment (tx) of unresected stage IIIB/C and IV melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(Suppl):Abstract 9008. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Faries MB, Hsueh EC, Ye X, et al. Effect of granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor on vaccination with an allogeneic whole-cell melanoma vaccine. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(22):7029–35. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]