Abstract

BACKGROUND

Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) represents a diverse category of myogenic malignancies with marked differences in molecular alterations and histology. This study examines the question if RMS predisposition due to germline TP53 mutations correlates with certain RMS histologies.

METHODS

The histology of RMS tumors diagnosed in 8 consecutive children with TP53 germline mutations was reviewed retrospectively. In addition, germline TP53 mutation analysis was performed in 7 children with anaplastic RMS (anRMS) and previously unknown TP53 status.

RESULTS

RMS tumors diagnosed in 11 TP53 germline mutation carriers all exhibited nonalveolar, anaplastic histology as evidenced by the presence of enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei with or without atypical mitotic figures. Anaplastic RMS was the first malignant diagnosis for all TP53 germline mutation carriers in this cohort, and median age at diagnosis was 40 months (mean, 40 months ± 15 months; range, 19-67 months). The overall frequency of TP53 germline mutations was 73% (11 of 15 children) in pediatric patients with anRMS. The frequency of TP53 germline mutations in children with anRMS was 100% (5 of 5 children) for those with a family cancer history consistent with Li-Fraumeni syndrome (LFS), and 80% (4 of 5 children) for those without an LFS cancer phenotype.

CONCLUSIONS

Individuals harboring germline TP53 mutations are predisposed to develop anRMS at a young age. If future studies in larger anRMS cohorts confirm the findings of this study, the current Chompret criteria for LFS should be extended to include children with anRMS irrespective of family history.

Keywords: rhabdomyosarcoma, anaplasia, TP53, germline mutations, Li-Fraumeni syndrome

INTRODUCTION

Soft tissue sarcomas (STSs) are a group of cancers arising in nonhematopoietic, mesodermal tissues. Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS), the most common STS in children and adolescents, represents a diverse sarcoma category as evidenced by marked differences in histology, myogenic differentiation, oncogenic pathway activation, and mutational spectrum.1,2 The contributions of specific RMS-relevant pathways to the formation of RMS have been tested extensively in mice.3-5 It is clear that, in mouse models, aberrations in distinct oncogenic pathways correlate with the induction of RMS tumors that share uniform histological appearance,6 such as pleomorphic RMS due to inactivation of TP53 with or without introduction of oncogenic Kras3,5 and highly differentiated RMS due to activation of Sonic Hedgehog signaling.4,7

This study builds on the hypothesis that the phenotype of RMS arising in the setting of sarcoma-predisposing germline lesions may offer a unique window into the genetic origins and biological identity of certain RMS sub-types. In humans, genetic susceptibility to develop RMS has been linked to germline mutations in PTCH1, HRAS, NF1, DICER1, and TP53.8-16 In a previous study, 3 of 13 children with RMS diagnosed under 3 years of age, including 1 child with alveolar RMS and 2 children with nonalveolar RMS, were found to have TP53 germline mutations. None of 23 children with RMS diagnosed at older than 3 years of age harbored TP53 germline lesions.11 These findings prompted recommendations to screen children diagnosed with RMS under the age of 36 months for the presence of TP53 germline mutations. Our review of 8 RMS tumors arising in children with TP53 germline mutations revealed that these tumors uniformly exhibited anaplasia, a distinctive histological subtype characterized by enlarged, hyperchromatic nuclei. In addition, 3 of 7 children with anaplastic RMS (anRMS) and previously unknown TP53 germline mutation status were determined to harbor TP53 germline mutations. Median age at diagnosis of anRMS in these 11 TP53 germline mutation carriers was 40 months (range, 19-67 months). These findings support the notion that TP53 pathway activation contributes to the biology of anRMS and, similar to observations in Wilms tumors and medulloblastoma,17,18 drives target cells for malignant transformation to assume an anaplastic phenotype.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Selection and Clinical Data

Patients with RMS were selected as follows: 1) For the first exploratory cohort of patients (Table 1, cases 1-8), 8 children with RMS and TP53 germline mutations seen consecutively at Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA, and the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Ontario, Canada since January 1 1985 were identified; and 2) for the expanded cohort (Table 1, cases 9-15), 7 children with anRMS and previously unknown TP53 germline mutation status19-21 were evaluated. This study was approved by the institutional review boards at both institutions. Pathology specimen from the 3 RMS tumors diagnosed in TP53 germline mutation carriers and reported by Diller et al in 1995 could not be retrieved11; these cases therefore were not included in the cohort evaluated here.

TABLE 1.

TP53 Germline Mutations in 15 Children With Anaplastic Rhabdomyosarcoma (anRMS)a

| Case ID | Sex | Age at Dx (mo) | anRMS | TP53 IHC | Personal Hx of Cancer | Family Hx of LFS Cancer | TP53 Germline Mutation | De Novo Mutation | Mutation Type | Exon | Previously Published |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 40 | + | + | Unknown | + | IVS3-11 C>G | Inherited | Splice site mutation | – | Varley et al (2001) |

| 2 | M | 45 | + | 0 | Unknown | + | c.375G>A; p.T125T | Inherited | Altered splicing | Exon 4 | Ruijs et al (2010) |

| 3 | F | 34 | + | + | None | + | c.534C>G; p.H178Q | Unknown | Substitution, nonsense | Exon 5 | Wozniak et al (2011) |

| 4 | F | 64 | + | 0 | AC, Sarcoma | + | IVS05-1 G>C | De novo | Splice site mutation | – | |

| 5 | M | 50 | + | + | OS, AC | 0 | c.1024C>T; p.R342X | Unknown | Substitution, nonsense | Exon 10 | Gonzalez et al (2009) |

| 6 | M | 33 | + | 0 | OS | 0 | 12138 insC; p.P72fs | Inherited | Insertion, frameshift | Exon 4 | – |

| 7 | M | 28 | + | + | None | 0 | c.916C>T; p.R306X | Unknown | Substitution, nonsense | Exon 8 | Cornelis et al (1997) |

| 8 | F | 24 | + | 0 | Unknown | 0 | c.438G>A; p.W146X | De novo | Substitution, nonsense | Exon 5 | – |

| 9 | M | 19 | + | n/a | None | + | c.880dup; p.E294fs | Unknown | Duplication, frameshift | Exon 8 | – |

| 10 | F | 67 | + | n/a | None | Unknown | c.375G>A; p.T125T | Unknown | Altered splicing | Exon 4 | Bougeard et al (2008) |

| 11 | M | 40 | + | n/a | None | Unknown | IVS376-1 G>A | Unknown | Splice site mutation | – | – |

| 12 | F | 120 | + | n/a | None | Unknown | – | – | – | – | – |

| 13 | M | 75 | + | n/a | None | Unknown | – | – | – | – | – |

| 14 | M | 43 | + | n/a | None | 0 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 15 | M | 150 | + | n/a | Unknown | Unknown | – | – | – | – | – |

Abbreviations: AC, adenocarcinoma; Dx, diagnosis; Hx, history; IHC, immunohistochemistry; LFS, Li-Fraumeni syndrome; n/a, not available; OS, osteosarcoma.

Cases 1-8 represent an exploratory cohort of 8 consecutive children with known TP53 germline mutations and RMS. Cases 9-15 form a secondary cohort of 7 children with anRMS and previously unknown TP53 germline mutation status. Immunohistochemical staining for TP53 was graded as present (+), absent (0) or not available (n/a). Family history of Li Fraumeni spectrum (LFS) cancers in first- or second-degree relatives was noted as present (+), absent (0) or unknown. Mutations were identified as inherited if one parent was found to carry the same TP53 germline mutation. Cases 2 and 10 carried the same germline TP53 mutation, previously published by Ruijs et al28 and Bougeard et al.31

Tumor histology, TP53 germline mutation status, family and personal history of LFS cancers, age at diagnosis, tumor site, International RMS Study Group (IRSG) grouping/staging information, and current clinical outcome were reviewed and recorded. Anaplasia was determined by L.A.T (Table 1, cases 1-15) and G.R.S (Table 1, cases 1-2, 4, 6, 8-15) based on the presence of enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei (at least 3 times the size of neighboring nuclei) with or without atypical mitotic figures.22,23 Nuclear staining for TP53 by immunohisto-chemistry (IHC) was graded as present or absent.

TP53 Mutation Testing

Germline DNA was evaluated for TP53 mutations only. TP53 mutation analysis was performed on genomic DNA extracted from peripheral blood lymphocytes in the clinical CLIA-CAP molecular diagnostic laboratories at both institutions. Germline DNA was collected shortly after diagnosis for 14 of 15 patients (Table 1, cases 1-4 and 6-15) and after the child's third malignant diagnosis for 1 patient (Table 1, case 5). Sequencing of exons 1 through 11 including 20-50 bases into introns and the 5′/3′-untranslated region was performed, in addition to multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) analysis of gene copy number. All mutations were previously reported in the germline (IARC database, R16, November 2012; Petitjean et al24), or predicted aberrant function based on introduction of a termination codon or disruption of a splice site. Mutations were identified as de novo if both parents had normal TP53 germline status. Mutations were identified as inherited if one parent carried the same TP53 germline mutation. Inheritance status was reported as unknown if germline sequencing data on the parents were not available.

Statistics

This study was designed as a retrospective review of a rare pediatric disease. Due to the small sample size, testing for statistical significance was not possible.

RESULTS

RMS Tumors in TP53 Germline Mutation Carriers Exhibit Anaplastic Histology

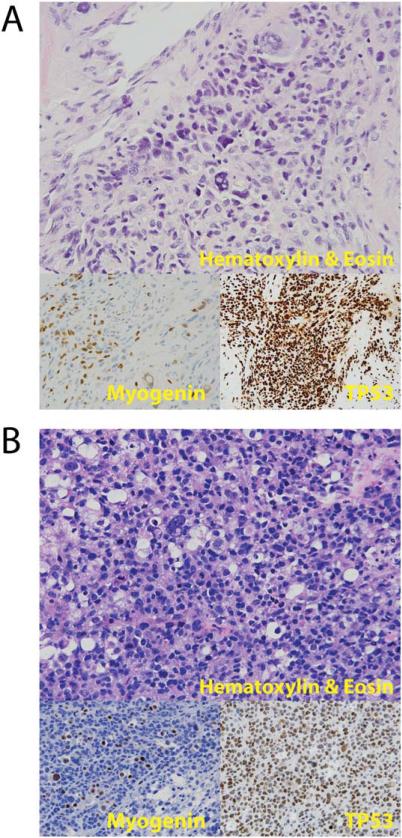

To determine whether the presence of TP53 germline mutations correlates with susceptibility to develop RMS with specific histological features, we retrospectively reviewed tumor histology in 8 consecutive patients with RMS and TP53 germline mutations (Table 1, cases 1-8). These 8 children had previously undergone TP53 germline analysis, because they had first- or second degree relatives with cancers of the LFS spectrum (Table 1, cases 1-4), a personal history of multiple LFS cancers (Table 1, case 5) and/or were diagnosed with RMS under the age of 3 years (Table 1, cases 3, 6-8).11 All 8 tumors exhibited nonalveolar anaplastic morphology (Table 1 and Fig. 1). IHC staining for desmin and myogenin was positive in all tumors (Fig. 1 and data not shown). Nuclear staining for TP53 was positive in ≥ 50% of tumor nuclei in 4 of these tumors (Fig. 1 and Table 1). TP53 staining was absent in the remaining 4 tumors (Table 1). Of note, case 5 (Table 1, Fig. 1B) was originally described as a fusion-negative, solid-variant alveolar RMS in 2002. On re-review by L.A.T, the histological appearance, focal nuclear staining for myogenin, and cytogenetics were most consistent with a diagnosis of nonalveolar RMS. Diffuse anaplasia was present.

Figure 1.

Histology micrographs show anaplastic rhabdomyosarcoma (anRMS) in TP53 germline mutation carriers. (A) Diffuse anaplasia noted on hematoxylin & eosin (H&E)-stained sections of a RMS in the retroperitoneum of a 34-month-old female TP53 germline mutation carrier (Table 1, case 3). (B) Diffuse anaplasia on H&E-stained sections of a RMS of the lower pelvis in a 50-month-old male TP53 mutation carrier (Table 1, case 5).

Many Children With anRMS Carry TP53 Germline Mutations

To further evaluate the association of TP53 germline mutations and anRMS, we performed TP53 mutation analysis on genomic DNA obtained from peripheral blood lymphocytes from 7 additional children with anRMS (Table 1, cases 9-15). One of these 7 children had first- and second-degree relatives with LFS cancers (Table 1, case 9). For the remaining 6 children, family history was negative for LFS cancers or not available. Functionally relevant germline mutations at the TP53 locus were detected in 3 of these 7 children (Table 1, cases 9-11). Thus, of 15 children with anRMS included in this study, 11 (73%) had a TP53 germline mutation.

TP53 Germline Mutations in Children With anRMS

TP53 mutations in 6 children with anRMS included in this study comprised single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) in the coding sequence of exons 4, 5, 8, and 10 of human TP53 resulting in nonsense mutations (Table 1, cases 3, 5, 7, 8) or altered splicing (Table 1, cases 2 and 10). SNVs in the non-coding sequence of TP53, resulting in splice site mutations, were observed in 3 patients (Table 1, cases 1, 4, 11). Frameshift mutations in exons 4 and 8 of TP53 were found in 2 patients (Table 1, cases 6 and 9). Aberrations at all 8 mutation sites within the TP53 coding sequence were previously reported in the UMD TP53 database (Table 1, cases 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10; http://p53.free.fr/Database/p53_database.html; Soussi et al25). Four mutations were previously reported in the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (Table 1, case 3/COSM46163, case 5/COSM306146, case 7/COSM10663, case 8/COSM10727). Six of 11 mutations (Table 1; cases 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 10) were previously published in patients with LFS.26-31 The remaining 5 mutations were functionally relevant, because they either encoded a premature termination codon predicting a truncated protein or harbored a mutation predicting disruption of exon splicing.

anRMS in Children With TP53 Germline Mutations Often Presents at a Young Age and May Not Be Associated With LFS Cancers in the Family

Median age at anRMS diagnosis in TP53 germline mutation carriers was 40 months (mean, 40 ± 15 months; range, 19-67 months). Five of 11 TP53 germline mutation carriers were diagnosed with anRMS under the age of 3 years, and the remaining 6 TP53 germline mutation carriers with anRMS were diagnosed between 3 and 7 years of age (Table 2). Thus, all 5 children (100%) diagnosed with anRMS under 3 years, and 6 of 8 children (75%) diagnosed with anRMS between 3 and 7 years of age were TP53 mutation carriers. Two children diagnosed with anRMS between 7 and 13 years of age did not have TP53 germline mutations.

TABLE 2.

Frequency of TP53 Germline Mutations in Children With Anaplastic Rhabdomyosarcoma (anRMS) Based on Age and Family History of LFS Cancers

| Children With anRMS No. (%) | Children With anRMS and Mutated TP53 No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | ||

| 0-3 years | 5 (of 15, 33%) | 5 (of 5, 100%) |

| 3-7 years | 8 (of 15, 53%) | 6 (of 8, 75%) |

| 7-13 years | 2 (of 15, 13%) | 0 (of 2, 0%) |

| Family history in at least one first- or second-degree relative | ||

| No LFS cancers | 5 (of 10, 50%) | 4 (of 5, 80%) |

| Any LFS cancers | 5 (of 10, 50%) | 5 (of 5, 100%) |

| LFS core-cancers | 3 (of 10, 30%) | 3 (of 3, 100%) |

Abbreviations: anRMS, anaplastic rhabdomyosarcoma; LFS, Li-Fraumeni syndrome.

Age at diagnosis was available for review for all 15 children; family history was available for 9 children. Rhabdomyosarcoma was the first malignant diagnosis in all patients. LFS core cancers include soft tissue sarcoma, osteosarcoma, brain tumor, premenopausal breast cancer, adrenocortical carcinoma, leukemia, and lung bronchoalveolar cancer.

Family history of cancer in first- and second-degree relatives was available for 9 of 11 children with TP53 germline mutations and anRMS (Table 1 and Supporting Table 1; see online supporting information). Five of these children (56%) had at least one first- or second-degree relative with a malignancy on the LFS spectrum, including 3 children with family members with LFS core cancers such as osteosarcoma, glioblastoma, and adrenocortical carcinoma. However, 4 children (36%) with TP53 germline mutations and anRMS did not have any family history of LFS cancers (Table 2). The frequency of germline TP53 mutations in children with anRMS was 100% (5 of 5 children) for those with a family cancer history consistent with Li-Fraumeni syndrome (LFS), and 80% (4 of 5 children) for those without an LFS cancer phenotype.

Current LFS Classification Schemes Do Not Capture All Children With anRMS and TP53 Germline Mutations

Based on family history alone, 3 children in this anRMS cohort fit classic LFS criteria (Table 1 and Supporting Table 1, cases 2 and 9; and Supporting Table 2)32 or Birch/Eeles criteria for Li-Fraumeni–like syndrome (LFL) (Table 1 and Supporting Table 1, case 1; and Supporting Table 2).33,34 Chompret criteria for LFS consider both family and personal history of cancer. Seven children with anRMS and TP53 germline mutations met Chompret criteria at the time of this review (Table 1 and Supporting Table 1, cases 1-6,9; and Supporting Table 2).19-21 Yet, none of the current LFS classification schemes captured all TP53 germline mutation carriers.

anRMS in TP53 Germline Mutation Carriers Often Present With Group III Tumors at Unfavorable Disease Sites

International RMS Study Group (IRSG) grouping/staging information was available on 9 (stage)/10 (group) germline TP53 mutation carriers in this cohort, and primary tumor site was available on all 11 children (Table 3 and Supporting Table 3). The majority of patients with mutated germline TP53 had IRSG group III tumors (gross residual disease after initial surgical intervention). Distant metastases at diagnosis were only present in one child who carried a TP53 splice site mutation (Table 3, case 1). Seven of 11 anRMS tumors in TP53 germline mutation carriers arose at unfavorable disease sites in the extremities, trunk or parameningeal space (Supporting Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Primary Tumor Site, IRS Group/Stage and Survival of 15 Children With Anaplastic Rhabdomyosarcoma

| Case ID | Primary Tumor Site | IRS Group/Stage | Survival |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Paraspinal | Group IV, stage 4 | DOD (19 mo) |

| 2 | Right triceps muscle | Group III, stage 2 | NED (24 mo) |

| 3 | Retroperitoneum | Group III, stage 3 | In Tx (23 mo) |

| 4 | Oral cavity | Group III, stage 1 | DOSM (125 mo) |

| 5 | Lower pelvis | Group III, stage 3 | NED (123 mo) |

| 6 | Left gluteus maximus | Group III | DOSM (128 mo) |

| 7 | Right thigh | Group III, stage 3 | NED (14 mo) |

| 8 | Left pterygoid muscle | Group III, stage 3 | NED (140 mo) |

| 9 | Right orbit | Group III, stage 1 | In Tx (1 mo) |

| 10 | Right masseter muscle | n/a | DOD (62 mo) |

| 11 | Left chest wall | Group II, stage 2 | NED (59 mo) |

| 12 | Left orbit | n/a | NED (155 mo) |

| 13 | Right pterygoid muscle | Group III, stage 3 | DOD (11 mo) |

| 14 | Right paratesticular | Group I, stage 1 | NED (39 mo) |

| 15 | Infratemporal fossa | n/a | DOD (6 mo) |

Abbreviations: DOD, dead of disease; DOSM, dead of second malignancy; In Tx, in treatment; IRS, International RMS Study Group; n/a, not available; NED, no evidence of disease.

Cases 1-11 were TP53 germline mutation carriers; cases 12-15 did not have TP53 germline mutations. Two children were undergoing treatment for primary anRMS (case 9) or relapsed anRMS (case 3) at the time of this review.

TP53 Germline Mutation Carriers With anRMS Are at Risk for Additional Malignancies

Qualman et al reported 68% 5-year overall survival in pediatric patients with anRMS, and correlated anaplasia with inferior outcome in patients with intermediate-risk embryonal RMS.23 Of 11 children with anRMS and TP53 germline mutations reported here, 5 children were alive and without evidence of disease at 14 to 155 months after first diagnosis (Table 3 and Supporting Table 3). Yet, 3 TP53 germline mutation carriers with anRMS developed second malignancies typical of the LFS spectrum (including one patient with an osteosarcoma in the radiation field, Table 1, case 5). Two of these children died from their second cancers (Table 3 and Supporting Table 3, cases 4 and 6).

DISCUSSION

LFS is an inherited cancer predisposition syndrome characterized by early onset cancers, including but not limited to STS, osteosarcoma, adrenocortical carcinoma, brain tumors and breast carcinoma.32 The only gene that has been consistently associated with LFS is TP53.20 Several classification schemes were developed to identify individuals at risk for germline TP53 mutations based on family history of cancer in first- and second-degree relatives.32-34 More recently, Chompret et al developed criteria that allow for the possibility of a negative family history in individuals with at least 2 LFS spectrum cancers, adreno-cortical carcinoma or choroid plexus tumor.19-21 Adreno-cortical carcinoma is considered to be a sentinel cancer in TP53 germline mutation carriers, as the frequency of TP53 germline mutations in 21 children with adrenocortical carcinoma was found to be 67%.20 We determined that 11 of 15 children with anRMS included in our cohort had TP53 germline mutations. Although adrenocortical carcinomas appeared to be more common in female TP53 germline mutation carriers,20 7 of 11 children with anRMS and germline TP53 mutations in this cohort were males (Table 1). Our findings suggest that anRMS represents another sentinel cancer in LFS. If future studies in larger anRMS cohorts confirm these findings, the Chompret criteria for LFS should be extended to include children with anRMS irrespective of family history.

Anaplastic RMS is a distinctive RMS subtype22,23 and shares certain histological features with pleomorphic RMS, historically considered a major form of RMS in adults and recently found to account for 19% of RMS in individuals aged > 19 years.35 Yet, anaplastic histology (the preferred term in the pediatric age group) in children with RMS is rare. Anaplasia was detected in 3% of all cases of RMS studied in the first 3 Intergroup RMS Studies (IRS I-III),22 and in 13% of RMS included in Intergroup RMS Study Group (IRSG) or COG therapeutic trials from 1995 to 1998.23 Both studies noted that focal and diffuse patterns of anaplasia were present across the entire RMS spectrum, including alveolar and nonalveolar tumors.22,23 In fact, one TP53 germline mutation carrier in this cohort was initially diagnosed with fusion-negative solid-variant alveolar RMS (Table 1, case 5). However, on re-review by LAT, the tumor was reclassified as a nonalveolar tumor with diffuse anaplasia. Thus, all 11 TP53 germline mutation carriers with anRMS included in our cohort had fusion-negative tumors on the nonalveolar spectrum.

TP53 germline mutations were previously linked to both alveolar and nonalveolar RMS, the 2 main RMS subgroups. Many alveolar RMS tumors carry exclusive fusions of the DNA binding domain of the PAX3 or PAX7 genes to the transactivation domain of the Foxo1a gene.36 TP53 mutations were reported in 2 PAX3:-FOXO1a-positive human alveolar RMS cell lines (Rh41 and Rh30),8,37 but it is not known if the TP53 mutations in these cell lines originated in the patients’ germlines, tumors, or during ex vivo culture. Moreover, Takahashi et al reported TP53 mutations of unknown germline status in 4 alveolar tumors,38 and Diller et al described a TP53 germline mutation in one child with alveolar RMS.11 However, the fusion status of these 5 TP53-mutated alveolar tumors was not reported, and we were unable to verify alveolar histology of the case reported by Diller et al,11 because the pathology specimen could not be retrieved. Future studies are needed to evaluate germline TP53 mutations in children with fusion-positive alveolar RMS and to determine if TP53 germline mutations confer susceptibility to develop human fusion-positive alveolar RMS with or without anaplasia.

Because both anRMS and TP53 germline mutations are rare occurences, it is remarkable that the RMS tumors diagnosed in 11 TP53 germline mutation carriers all exhibit anaplasia. Two lines of evidence in the published literature support the hypothesis that TP53 pathway activation contributes to the biology of anRMS: 1) inactivation of TP53 with or without introduction of oncogenic Kras in skeletal muscle cells results in formation of high-grade pleomorphic RMS in mice3,5,39; and 2) anaplastic variants of other embryonal tumors (ie, Wilms tumor and medulloblastoma) were previously linked to germline and somatic mutations disrupting the p53 pathway.17,18,40,41 It is conceivable that early (germline), inactivating TP53 mutations preferentially drive target cells for sarcomatous transformation to assume an anaplastic phenotype, perhaps due to early catastrophic DNA rearrangements as previously reported in medulloblastomas arising in the context of TP53 germline mutations.41

Heerema-McKenney et al previously surveyed TP53 staining by IHC in 64 RMS tumors, and reported TP53 positivity in 5% to 50% of tumor nuclei in 10 tumors, and in < 5% of tumor nuclei in 54 tumors.42 In our cohort, TP53 expression was evaluated by IHC in 8 anRMS tumors arising in TP53 germline mutation carriers (Table 1, cases 1-8). Nuclear TP53 staining was positive in ≥ 50% of tumor cells in 4 tumors arising in children with mutations predicted to stabilize the protein. Absence of TP53 in the remaining 4 tumors correlated with the presence of germline TP53 mutations that predicted a truncated or deleted product. These observations further support that loss of TP53 function contributes importantly to the biology of anRMS.

It is important to note that 4 of 15 children with anRMS included in this cohort did not have TP53 germline mutations. Future studies are needed to investigate the presence of inactivating, somatic mutations in anRMS in children with a wild-type germline TP53 genotype. We also note that, because this study was focused on evaluating TP53 germline mutations in children with anRMS, our findings do not offer insight into the potential contributions of germline mutations in other RMS-relevant genes or into the overall prevalence of pathogenic germline mutations in children with RMS.

Finally, recent efforts to classify other pediatric malignancies such as medulloblastomas into genetically distinct subgroups have identified disease subsets with marked differences in outcome and therapeutic susceptibilities43; in a similar fashion, the distinction of TP53-driven anRMS could have clinical implications. In our cohort, 9 of 11 children with TP53 germline mutations and anRMS presented as group III tumors (incomplete resection with gross residual disease) and 7 of 11 arose at unfavorable sites. 5 of 11 TP53 germline mutation carriers with a history of anRMS were alive and without evidence of disease at 14 to 155 months after first diagnosis, but 3 children developed second malignancies (including one patient with an osteosarcoma in the radiation field) and 2 of these died from their second cancers. Extended studies in larger cohorts of patients are needed to define the prevalence, clinical behavior, and specific therapeutic requirements (especially with regards to the use of radiation therapy for local control) of anRMS in TP53 germline mutation carriers.

Early identification of TP53 germline mutations is important, as it may allow for subsequent surveillance and early diagnosis of second malignancies.44 Here, we report a strong association between germline TP53 mutations and anRMS diagnosed at a young age, and propose considering TP53 mutation screening for children diagnosed with anRMS irrespective of family history. However, in the absence of TP53 germline data on young children diagnosed with nonanaplastic RMS, our findings do not support changes in existing TP53 mutation screening recommendations for young children diagnosed with any type of RMS under the age of 3 years. Extended studies will be needed to define the specific role of TP53, both in the germline and at a somatic level, in anRMS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

FUNDING SOURCES

The authors declare no competing financial interests. This work was supported in part by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP106639) (DM), by the SickKids Foundation (DM), by a SARC-SPORE career development award (SH) and by a Stand Up To Cancer-American Association for Cancer Research Innovative Research Grant, grant number SU2C-AACR-IRG1111 (AJW). AJW is an Early Career Scientist of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding sources.

Footnotes

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

The authors are grateful to Holcombe E. Grier for constructive comments on the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

The authors made no disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Parham DM. Pathologic classification of rhabdomyosarcomas and correlations with molecular studies. Mod Pathol. 2001;14:506–514. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xia SJ, Pressey JG, Barr FG. Molecular pathogenesis of rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer Biol Ther. 2002;1:97–104. doi: 10.4161/cbt.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doyle B, Morton JP, Delaney DW, Ridgway RA, Wilkins JA, Sansom OJ. p53 mutation and loss have different effects on tumourigenesis in a novel mouse model of pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma. J Pathol. 2010;222:129–137. doi: 10.1002/path.2748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hahn H, Wojnowski L, Zimmer AM, Hall J, Miller G, Zimmer A. Rhabdomyosarcomas and radiation hypersensitivity in a mouse model of Gorlin syndrome. Nat Med. 1998;4:619–622. doi: 10.1038/nm0598-619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsumura H, Yoshida T, Saito H, Imanaka-Yoshida K, Suzuki N. Cooperation of oncogenic K-ras and p53 deficiency in pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma development in adult mice. Oncogene. 2006;25:7673–7679. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rubin BP, Nishijo K, Chen HI, et al. Evidence for an unanticipated relationship between undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma and embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:177–191. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corcoran RB, Scott MP. A mouse model for medulloblastoma and basal cell nevus syndrome. J Neurooncol. 2001;53:307–318. doi: 10.1023/a:1012260318979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ayan I, Luca J, Jaffe N, Strong L, Hansen M. De novo germline mutations of the p53 gene in young children with sarcomas. Oncol Rep. 1997;4:679–683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beddis IR, Mott MG, Bullimore J. Case report: nasopharyngeal rhabdomyosarcoma and Gorlin's naevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1983;11:178–179. doi: 10.1002/mpo.2950110309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cajaiba MM, Bale AE, Alvarez-Franco M, McNamara J, Reyes-M ugica M. Rhabdomyosarcoma, Wilms tumor, and deletion of the patched gene in Gorlin syndrome. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2006;3:575–580. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diller L, Sexsmith E, Gottlieb A, Li FP, Malkin D. Germline p53 mutations are frequently detected in young children with rhabdomyosarcoma. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:1606–1611. doi: 10.1172/JCI117834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Estep AL, Tidyman WE, Teitell MA, Cotter PD, Rauen KA. HRAS mutations in Costello syndrome: detection of constitutional activat ing mutations in codon 12 and 13 and loss of wild-type allele in malignancy. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140:8–16. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heney D, Lockwood L, Allibone EB, Bailey CC. Nasopharyngeal rhabdomyosarcoma and multiple lentigines syndrome: a case report. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1992;20:227–228. doi: 10.1002/mpo.2950200309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kratz CP, Rapisuwon S, Reed H, Hasle H, Rosenberg PS. Cancer in Noonan, Costello, cardiofaciocutaneous and LEOPARD syndromes. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2011;157:83–89. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steenman M, Westerveld A, Mannens M. Genetics of Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome-associated tumors: common genetic pathways. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2000;28:1–13. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2264(200005)28:1<1::aid-gcc1>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doros L, Yang J, Dehner L, et al. DICER1 mutations in embryonal rhabdomyosarcomas from children with and without familial PPB-tumor predisposition syndrome. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;59:558–560. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bardeesy N, Falkoff D, Petruzzi MJ, et al. Anaplastic Wilms’ tumour, a subtype displaying poor prognosis, harbours p53 gene mutations. Nat Genet. 1994;7:91–97. doi: 10.1038/ng0594-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frank AJ, Hernan R, Hollander A, et al. The TP53-ARF tumor suppressor pathway is frequently disrupted in large/cell anaplastic medulloblastoma. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2004;121:137–140. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2003.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chompret A, Abel A, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, et al. Sensitivity and predictive value of criteria for p53 germline mutation screening. J Med Genet. 2001;38:43–47. doi: 10.1136/jmg.38.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gonzalez KD, Noltner KA, Buzin CH, et al. Beyond Li Fraumeni Syndrome: clinical characteristics of families with p53 germline mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1250–1256. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.6959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tinat J, Bougeard G, Baert-Desurmont S, et al. 2009 version of the Chompret criteria for Li Fraumeni syndrome. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:e108–e109. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.7967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kodet R, Newton WA, Jr, Hamoudi AB, Asmar L, Jacobs DL, Maurer HM. Childhood rhabdomyosarcoma with anaplastic (pleomorphic) features. A report of the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993;17:443–453. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199305000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qualman S, Lynch J, Bridge J, et al. Prevalence and clinical impact of anaplasia in childhood rhabdomyosarcoma: a report from the Soft Tissue Sarcoma Committee of the Children's Oncology Group. Cancer. 2008;113:3242–3247. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petitjean A, Mathe E, Kato S, et al. Impact of mutant p53 functional properties on TP53 mutation patterns and tumor phenotype: lessons from recent developments in the IARC TP53 database. Hum Mutat. 2007;28:622–629. doi: 10.1002/humu.20495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soussi T, Asselain B, Hamroun D, et al. Meta-analysis of the p53 mutation database for mutant p53 biological activity reveals a methodologic bias in mutation detection. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:62–69. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cornelis RS, van Vliet M, van de Vijver MJ, et al. Three germline mutations in the TP53 gene. Hum Mutat. 1997;9:157–163. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1997)9:2<157::AID-HUMU8>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gonzalez KD, Buzin CH, Noltner KA, et al. High frequency of de novo mutations in Li-Fraumeni syndrome. J Med Genet. 2009;46:689–693. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.058958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruijs MW, Verhoef S, Rookus MA, et al. TP53 germline mutation testing in 180 families suspected of Li-Fraumeni syndrome: mutation detection rate and relative frequency of cancers in different familial phenotypes. J Med Genet. 2010;47:421–428. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.073429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Varley JM, Attwooll C, White G, et al. Characterization of germline TP53 splicing mutations and their genetic and functional analysis. Oncogene. 2001;20:2647–2654. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wozniak A, Fryer A, Grimer R, Mc Dowell H. Multiple malignancies in a child with de novo TP53 mutation. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011;28:338–343. doi: 10.3109/08880018.2010.548439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bougeard G, Sesboüé R, Baert-Desurmont S, et al. Molecular basis of the Li-Fraumeni syndrome: an update from the French LFS families. J Med Genet. 2008;45:535–538. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.057570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li FP, Fraumeni JF, Jr, Mulvihill JJ, et al. A cancer family syndrome in twenty-four kindreds. Cancer Res. 1988;48:5358–5362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Birch JM, Hartley AL, Tricker KJ, et al. Prevalence and diversity of constitutional mutations in the p53 gene among 21 Li-Fraumeni families. Cancer Res. 1994;54:1298–1304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eeles RA. Germline mutations in the TP53 gene. Cancer Surv. 1995;25:101–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sultan I, Qaddoumi I, Yaser S, Rodriguez-Galindo C, Ferrari A. Comparing adult and pediatric rhabdomyosarcoma in the surveillance, epidemiology and end results program, 1973 to 2005: an analysis of 2,600 patients. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3391–3397. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.7483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sorensen PH, Lynch JC, Qualman SJ, et al. PAX3-FKHR and PAX7-FKHR gene fusions are prognostic indicators in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma: a report from the children's oncology group. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2672–2679. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.03.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Felix CA, Kappel CC, Mitsudomi T, et al. Frequency and diversity of p53 mutations in childhood rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer Res. 1992;52:2243–2247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takahashi Y, Oda Y, Kawaguchi K, et al. Altered expression and molecular abnormalities of cell-cycle-regulatory proteins in rhabdomyosarcoma. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:660–669. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kirsch DG, Dinulescu DM, Miller JB, et al. A spatially and temporally restricted mouse model of soft tissue sarcoma. Nat Med. 2007;13:992–997. doi: 10.1038/nm1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Birch JM, Alston RD, McNally RJ, et al. Relative frequency and morphology of cancers in carriers of germline TP53 mutations. Oncogene. 2001;20:4621–4628. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rausch T, Jones DT, Zapatka M, et al. Genome sequencing of pediatric medulloblastoma links catastrophic DNA rearrangements with TP53 mutations. Cell. 20. 2012;148:59–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heerema-McKenney A, Wijnaendts LC, Pulliam JF, et al. Diffuse myogenin expression by immunohistochemistry is an independent marker of poor survival in pediatric rhabdomyosarcoma: a tissue microarray study of 71 primary tumors including correlation with molecular phenotype. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:1513–1522. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31817a909a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Northcott PA, Shih DJ, Peacock J, et al. Subgroup-specific structural variation across 1,000 medulloblastoma genomes. Nature. 2012;488:49–56. doi: 10.1038/nature11327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Villani A, Tabori U, Schiffman J, et al. Biochemical and imaging surveil-lance in germline TP53 mutation carriers with Li-Fraumeni syndrome: a prospective observational study. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:559–567. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70119-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.