Abstract

Objective

To conduct a series of focus groups with primary care physicians to determine the optimal format of a shortened, focused systematic review.

Materials and methods

Prototypes for two formats of a shortened systematic review were developed and presented to participants during focus group sessions. Focus groups were conducted with primary care physicians who were in full- or part-time practice. An iterative process was used so that the information learned from the first set of focus groups (Round 1) influenced the material presented to the second set of focus groups (Round 2). The focus group discussions were recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed.

Results

Each of the two rounds of testing included three focus groups. A total of 32 physicians participated (Round 1:16 participants; Round 2:16 participants). Analysis of the transcripts from Round 1 identified three themes including ease of use, clarity, and implementation. Changes were made to the prototypes based on the results so that the revised prototypes could be presented and discussed in the second round of focus groups. After analysis of transcripts from Round 2, four themes were identified, including ease of use, clarity, brevity, and implementation. Revisions were made to the prototypes based on the results.

Conclusions

Primary care physicians provided input on the refinement of two prototypes of a shortened systematic review for clinicians. Their feedback guided changes to the format, presentation, and layout of these prototypes in order to increase usability and uptake for end-users.

Keywords: evidence-based practice, focus groups, review literature as topic, qualitative research

Background and significance

Although research evidence is generated at an exponential rate,1 barriers to its use include challenges around access, interpretation, and appraisal.2 Systematic reviews of previously published studies of the effects of healthcare interventions are rigorous, comprehensive assessments of the evidence from those studies intended to help clinicians and others make informed decisions about healthcare.3 These systematic reviews are available to clinicians for practicing evidence-based medicine with the goal of delivering high quality patient care based on sound clinical decisions.4 However, despite the stated purpose of facilitating decision making5 and the concerted effort to enhance and clarify the methods of performing systematic reviews,6 their use in clinical decision making is not widespread.7 8 The excessive amount of time and effort required to use evidence resources is consistently identified as a significant obstacle to finding the answers to clinical questions.9–14

Creating filtered and tailored resources is one solution, where original studies and reviews are subject to explicitly formulated methodological criteria13 so that information can be validated and refined in order to be read quickly.15 This would allow for journal articles to be delivered in a way that is convenient, portable, and timely.16 Currently, many evidence-based products are available, for example, UpToDate. However, in an analysis of these online medical resources, authors concluded that no single source was ideal and those seeking answers to clinical questions were advised not to rely on a single product.17 As well, these tools are secondary sources, while this study focuses on reliably distilling data directly from the primary source. Two shortened systematic review formats were developed to enhance their use by clinicians18; the next step in the development process is to present these prototypes to clinicians for their input so they can be further refined. The purpose of this study was to conduct a series of focus groups with primary care physicians to determine the optimal format of a shortened systematic review.

Materials and methods

Development and description of the prototypes

The process of developing two alternate formats of a shortened systematic review to modify the presentation of information are described in a previous publication.18 In brief, prototypes for two formats of a shortened systematic review were developed in collaboration with a human factors engineer based on principles of user-centered design.18 The first format used a clinical scenario to present contextualized information (case-based format), and the second format integrated evidence and clinical expertise (evidence-expertise format). Both formats were developed using an explicit, rigorous process including a mapping exercise, a heuristic evaluation, and a clinical content review.19

Design

Focus groups were conducted to explore clinicians’ perceptions of the prototypes. Participants were asked about the presentation, layout, design, and content of the prototypes. Planning of the focus groups was based on a post-positivist paradigm that assumes it is possible to capture true representations of the real world.20–26 This approach strives to develop analyses that can be transferred from samples to broader populations, encouraging insights that extend beyond the realm of measurable, discoverable facts and include in-depth, detailed, rich data based on the individual's personal perspectives and experiences.24

Sampling and recruitment

Family physicians were identified as eligible for participation. Participants were recruited either through attendance at continuing education events or by snowball sampling27 which relies on referrals from the initial subjects to identify additional participants. Permission was received from the Office of Continuing Education and Professional Development in the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Toronto to recruit participants at formally planned educational events. Registered participants were either emailed prior to an educational event or asked at the event, for example, during a coffee break, if they would consider participating in a 1-hour focus group scheduled during their lunch period.

Ethics approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Review Boards of the University of Toronto and St Michael's Hospital, Toronto, Canada. Written informed consent was obtained. Participants were assured of confidentiality when the results of the focus groups were reported. A catered lunch and an honorarium were provided to participants.

Data collection

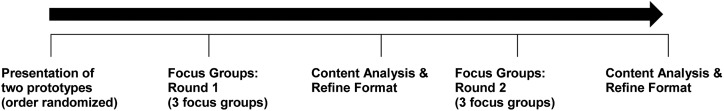

Iterative focus groups were planned so that the information learned from the first set of focus groups influenced the material presented in the second set of focus groups. Both shortened formats (cased-based and evidence-expertise) of the systematic review were presented during each focus group session (see online supplementary appendix A), and the order in which they were presented was randomized as depicted in figure 1. A random sequence was generated by a computer technician using MySQL's rand() function.28 Three to five focus groups were planned for each iteration with approximately four to eight participants in each group. Once saturation of themes was identified, the focus groups were halted. Groups were led by a moderator and a research assistant was present to record observations. All sessions were digitally taped. After the transcripts for the first round of focus groups were analyzed, the results informed a series of recommendations that were given to a graphic designer to guide revisions to the prototypes. The altered prototypes were then used in the second round of focus groups to ask participants for further suggestions. Following the second round of focus group transcripts, recommendations were generated and used by the graphic designer to modify the prototypes.

Figure 1.

Focus group process.

At each focus group, a paper copy of the full-length systematic review and the two shortened formats were given to all participants. Participants were given time to become familiar with the full-length systematic review at the beginning of the session. After this, they were asked to examine the prototypes of the two shortened formats and give explicit suggestions on various aspects of the proposed format (such as the layout, the division and organization of information, major content sections), and to give recommendations for the best possible method of presenting the results of a systematic review.

These sessions were based on a pre-planned agenda of questions and an interview guide was prepared.29 The discussion was a balance between gaining answers to the questions, and hearing from each participant in their own words.30 In preparation for conducting the focus groups, a mock focus group was conducted by the moderator (LP) and co-investigator (MRK) with a group of six volunteers who were non-physicians. The purpose of this was to identify difficulties with questions and streamline processes (eg, equipment, timing). The six volunteer participants consisted of research personnel and trainees with previous experience in preparing, conducting, and analyzing focus groups. Feedback and suggestions were offered on improving the focus groups in a debriefing session.

Data analysis

Inductive content analysis and constant comparison were used to analyze the data. Field notes and focus group transcripts were reviewed, and a thematic approach was taken in the evaluation of the qualitative data. In particular, reading and re-reading transcripts was done to achieve immersion.31 32 Transcripts were coded using a set of codes generated by the moderator (LP) from initially reviewing terms of usability problems identified with medical information tools,33 then reviewing the interview guide and reflecting on the information being sought by the questions. A meeting with a second coder was held to identify discrepancies in coding and to refine the coding scheme. Refinements included removing, collapsing, and adding codes to better represent the data. All changes to the coding scheme were done by consensus. Following this, transcripts were coded independently by two investigators and a meeting was held after each transcript was received to resolve discrepancies. Once coded, the data were read and re-read so that groupings could be made within the codes and clustered into themes and sub-themes.34

Rigor and quality

Strategies to enhance rigor and quality were based on Lincoln and Guba's framework.35 Probing questions were used during the focus groups to increase understanding of the participants’ meaning.36 Transcripts were coded independently by two investigators and discussed until agreement was reached. Procedures were documented to create an audit trail of coding, category, and theme development.37 Direct quotes are given to support themes for transparency and for readers to judge whether the findings reflect participants’ perceptions. The focus group moderators or assistants had no relationship with any of the participants. To increase validity, two investigators analyzed and coded the verbal data independently. This process of investigator triangulation meant that any discoveries and findings emerged from the data through consensus among the investigators.

Results

The focus groups were 60 min in length. Three focus groups were held between December 2011 and January 2012 (Round 1). Two investigators (LP, MRK) coded the transcripts. Agreement was reached that no new information was being learned from participants and no further focus groups were conducted after three sessions.

Recommendations were given to a graphic designer who revised the prototypes (see online supplementary appendix B). These revised prototypes were used in the second set of focus groups which were held between May 2012 and July 2012 (Round 2). After three focus groups, two investigators (LP, MRK) coded the transcripts and came to agreement that no new information was being learned from participants, so no further focus groups were conducted. Recommendations were given to a graphic designer who revised the prototypes (see online supplementary appendix C).

Characteristics of participants

Round 1

Three focus groups were conducted with 16 primary care physicians (Group A: six participants; Group B: five participants; Group C: five participants) from two educational events (table 1). Twelve participants were between 30 and 49 years of age, three were between 50 and 65 years of age, and one person did not provide their age. Eleven participants worked in private offices or clinics, and six worked in community clinics or health centers. Free-standing walk-in clinics, academic health sciences centers, and community hospitals were listed by four participants each. Three participants identified a university or faculty of medicine, and one indicated a research unit.

Table 1.

Demographics and work profile of study participants*

| Round 1 Three focus groups (N=16) |

Round 2 Three focus groups (N=16) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| <30 | – | 1 |

| 30–39 | 6 | 4 |

| 40–49 | 6 | 2 |

| 50–59 | 1 | 4 |

| 60–65 | 2 | 2 |

| >65 | – | 1 |

| Sex | ||

| Women | 7 | 7 |

| Men | 9 | 7 |

| Area of practice | ||

| Family medicine | 16 | 14 |

| General internal medicine | – | – |

| Years in practice (years) | ||

| <5 | 4 | 3 |

| 5–10 | 3 | 2 |

| 11–15 | 3 | 2 |

| 16–25 | 5 | 3 |

| >25 | 1 | 4 |

| Work setting† | ||

| Private office/clinic (excluding free-standing walk-in clinics) | 11 | 14 |

| Community clinic/community health center | 6 | – |

| Free-standing walk-in clinic | 4 | 2 |

| Academic health sciences center | 4 | – |

| Community hospital | 4 | 1 |

| Nursing home/home for the aged | – | 2 |

| University/faculty of medicine | 3 | – |

| Administrative office | – | – |

| Research unit | 1 | – |

| Free-standing laboratory/diagnostic clinic | – | – |

| Other | – | – |

| Practice population | ||

| Inner city | 6 | 2 |

| Urban/suburban | 8 | 12 |

| Small town | – | – |

| Rural | 1 | – |

| Geographically isolated/remote | – | – |

| Other | 1 (Military) | – |

*Three people did not provide demographic information. †Participants listed all settings where they worked (up to four settings per person).

Round 2

Three focus groups were conducted with 16 primary care physicians (Group A: six participants; Group B: four participants; Group C: six participants) at two primary care group practices in the greater Toronto area (two in Toronto, Canada; one in Oakville, Canada). Participants’ age ranged from less than 30 years of age (one participant) to more than 65 years of age (one participant). Two participants did not provide their age or any other demographic information. The majority reported they practiced in an urban/suburban setting (12 participants) and two listed that they worked in an inner city setting.

Findings

Three themes were identified in Round 1 and four themes emerged in Round 2 (table 2). In both rounds, the information presented by participants focused on similar concerns. Although similar themes emerged, comments were more focused and granular in the second round of focus groups. For instance, an ‘ease of use’ theme emerged for the groups in Round 1 and Round 2, but in Round 1 the topics covered were broader, more numerous, and less specific.

Table 2.

Focus group themes and supportive quotes

| Theme/Sub-theme | Supportive quote |

|---|---|

| Round 1 | |

| Theme: Ease of use | Focus Group 1 Participant 6: I don't need all the words in here…I want it quick, simple. But I do want all the information there but I would want to be able to recognize it at a glance without having to say, ‘Well where was it on here?’ |

| Sub-theme: Convention | Focus Group 2 Participant 4: …the format's a little flipped…compared to an abstract that I would look at…it's just backward. |

| Sub-theme: Prominence and completeness | Focus Group 1 Participant 2: Then they should say so….[it] should be clearly stated. |

| Theme: Clarity | Focus Group 1 Participant 5: I'm not really clear on…is this a recommended approach to treatment or is this commonly what happens? |

| Sub-theme: Organizing information | Focus Group 1 Participant 1: present it in that…tabular sort of fashion, it would sort of lay it out in terms of it being much better. |

| Sub-theme: Rating evidence | Focus Group 2 Participant 3: … if I want a little more information, have the summary…methodology as well as the rating scale at the bottom. |

| Sub-theme: Credibility | Focus Group 1 Participant 5: …I'd want to know who the experts were and I'd want to know their drug company associations. |

| Sub-theme: Language | Focus Group 2 Participant 2: On the second page, ‘Symptom—Other.’ So they mean other than what is mentioned here? |

| Theme: Implementation | Focus Group 2 Participant 1: …if you mention the trade names, it's very user friendly. |

| Round 2 | |

| Theme: Ease of use | Focus Group 1 Participant 6: Somehow or other this has to be popped out at us, different than this. |

| Theme: Clarity | Focus Group 1 Participant 6: I think overall I'd want this to be organized in a way where it's…the best to the worst…that's how my eye should want to read it. |

| Theme: Brevity | Focus Group 2 Participant 1: It's just so repetitive…There's no randomized control trials available for evaluation but yet it's just way too much work to get there. |

| Theme: Implementation | Focus Group 3 Participant 6: So, if tetracycline is helpful, then I'd like to know what dose did they use? |

Round 1

Three major themes emerged in Round 1 of the focus groups: (1) ease of use; (2) clarity; and (3) implementation. Each theme is described in the following section. Table 2 lists all themes and sub-themes along with supportive quotes.

Ease of use

Participants indicated that material needed to be presented in an intuitive manner. One way to achieve this was to have associated information (such as treatment and ratings of evidence) presented together. Visual cues were also favored with recommendations such as bolding text and highlighting important information.

Convention

Following established conventions for journal articles was another method that emerged in the focus groups that contributed to making a document intuitive. For example, although participants did not explicitly request a structured abstract, it was noted that one prototype (the evidence-expertise format) had an abstract that was presented out of sequence (ie, the conclusion was presented first), and this was contrasted to the order of a structured abstract. As well, participants described several components of structured abstracts (eg, methods, results) independently as favored or necessary information. Similarly, each component of PICOS (participants, interventions, comparators, outcomes, study types), a standard framework designed to make the process of defining and designing a research question easier, was identified as necessary information.

Prominence and completeness

Participants indicated that if something was perceived to be important, it was necessary to flag this for users. Items that were discussed included placing the ‘clinical bottom line’ in a prominent position and finding a way to highlight this information (for the case-based format). Bolding text and bulleting information were described as strategies to highlight salient information. Alternatively, if something was not important, this did not mean it could be ignored. As an example, several boxes were left blank in a table for one prototype (case-based format) because no information was available. It was determined that if no information was available, this should be clearly indicated.

Clarity

Clarity was emphasized for different aspects of the prototypes pertaining to layout and content.

Organizing information

Tables were identified as a way of presenting information in a clear manner. They were used in both prototypes to organize information and this structure was favored. It was suggested that tables should be organized in a manner that had a rationale, such as alphabetically or by ranking evidence from high to low quality.

Rating evidence

A scale was used to rate evidence and participants wanted the evidence scale to be clearly linked to treatment, with this information listed in one column within a table. Information about the evidence scale (ie, the explanation for how it worked) should be offered on the same page as the treatment information, and presented unobtrusively at the bottom of the document. Participants were positive about the use of a scale for conveying information about evidence, and the evidence scale generated numerous comments about how it should be presented to make it more user friendly. Although there were many ideas and suggestions (eg, using letters instead of numbers; removing numbers and using filled-in circles only; not including circles), no consistent recommendation emerged.

Credibility

Conflict of interest was discussed as a concern and participants wanted adequate information so they could judge the credibility of the review (eg, clearly identify the source) as well as the expert opinion (eg, the name of the person and their institution).

Language

Vague language needed to be eliminated to minimize confusion. As an example, one table had a heading labeled ‘Symptom—Other’ and this was consistently identified as unclear. In the same table, participants were also confused about another heading labeled ‘Follow Up’ and whether this was related to the trials in the review or the treatment for patients. Another area that needed clarification was whether the review focused on patient evaluation or physician evaluation of treatment.

Implementation

Participants wanted information that would allow them to implement the intervention assessed in the systematic review although this information is not traditionally available in a review. Items not available in the full-length review were proposed as missing from the shortened formats, and participants predominantly focused on adding more information about treatment, such as the concentration or strength of drugs, directions for their use, cost of drugs, trade names of drugs, dosage, duration of treatment, and frequency of treatment, along with other treatment-related information. As well, more information about diagnosis, symptoms, and a general description of the disease were described as absent from the shortened format.

Round 2

Four themes emerged in Round 2 of the focus groups: (1) ease of use; (2) clarity; (3) brevity; and (4) implementation.

Ease of use

Participants felt that several key items should be more prominent. For example, on the evidence-expertise prototype, it was felt that the expert interpretation should be separated from the information about the review (participants, interventions, outcomes, study types, synopsis) that were found directly below. Other items that were indicated as needing more distinction on the prototypes included the meta-analysis, results, the expert interpretation, and the information about what has no evidence.

Clarity

Participants expected that information presented in the review was automatically ranked. For example, it was assumed that evidence was ranked from ‘best to worst.’ As well, it was indicated that symptoms should be ranked from mild to severe.

Brevity

It was felt that the prototypes included repetitive information that lengthened the documents. For example, no randomized controlled trials were found for several treatments and in each instance, it was reported that there was nothing to evaluate. It was pointed out that this information could be collapsed and reported in one statement, thus creating a shorter document that could be understood more rapidly. Participants consistently indicated that shorter was always better.

Implementation

The theme of wanting information that would allow participants to implement the intervention assessed in the systematic review emerged, similar to the first round of focus groups. Information such as trade names and dosage of drugs was consistently identified as missing information despite these not being available in the full-length document.

Discussion

The physicians in our study described their thoughts and preferences on the presentation, layout, and design of two shortened formats of a systematic review. Our findings of ease of use, clarity, and brevity are aligned with results reported by Opiyo et al38 who found summarized systematic review formats were associated with greater clarity and accessibility of information in understanding clinical outcomes when compared to full-length systematic reviews alone.

Although systematic reviews can focus on interventions, diagnostic test accuracy, or methodology,39 this review focused on interventions for rosacea. Participants offered many comments and suggestions about what could be added to the prototypes that went beyond the information available in the full-length systematic review, such as dosages for drugs. The study was limited to the information found in the full-length review and these results highlight a challenge to the presentation of research because it is often described with insufficient information to allow a clinician to implement it in practice.40 Oxman et al41 identified that additional information was also required by policymakers when using systematic reviews to make recommendations. Both PROSPERO, an international database of prospectively registered systematic reviews (crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO), and PRISMA, an evidence-based minimum set of items for reporting in systematic reviews and meta-analyses (prisma-statement.org), have specific requirements for authors around describing their interventions. Requests for more information about interventions by groups such as PROSPERO and PRISMA result in specific information for readers, and also provide clearer guidance to authors. In addition, journals need to support this approach and encourage authors to include more of the types of information clinicians use in making practical, front-line decisions related to patient care.

Study limitations

Several limitations must be mentioned with regards to this study. The study is focused on family physicians only. In addition, there was potential for a difference in the dynamics of the groups for Round 1 and Round 2, since Round 1 participants were recruited from educational events and were not overly familiar with each other. In contrast, Round 2 participants were recruited from family practices which meant they worked at least part of their time at the same location and were likely familiar with each other. Also, Round 2 participants were more homogeneous with respect to their workplace setting and practice population, for example, they were more likely to practice in a suburban private office. Finally, the focus groups consisted of Canadian physicians and their opinions or preferences may not be transferrable to primary care physicians practicing in other countries. However, common themes were found across the focus groups and this increases the likelihood they are relevant to physicians in other settings.37

Conclusion

We report on one step of a project that concentrates on refining the presentation and format of a shortened systematic review in collaboration with users. Describing this process and reporting the outcomes has made the development of the two prototypes transparent for users and publishers. For the next steps, a pilot study will determine the feasibility of a randomized trial where participants will be asked to examine either the prototypes or the full-length systematic review and apply the evidence to clinical scenarios.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Christine Marquez and Sarah Munce for their assistance in conducting the focus groups.

Footnotes

Contributors: SES conceived of the idea. LP and MRK conducted the focus groups and performed the coding and data analysis. LP wrote the manuscript and all authors provided editorial advice.

Funding: The Canadian Institutes of Health Research provided funding for this study (grant number 487776).

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The Ethics Review Boards of the University of Toronto and St Michael's Hospital, Toronto, Canada approved this study

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Groneberg-Kloft B, Quarcoo D, Scutaru C. Quality and quantity indices in science: use of visualization tools. EMBO Rep 2009;10:800–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartley J. Clarifying the abstracts of systematic literature reviews. Bull Med Libr Assoc 2000;88:332–7 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cochrane Collaboration. What are Cochrane Reviews? http://www.cochrane.org/about-us/newcomers-guide#reviews (accessed 4 Mar 2014)

- 4.Straus SE, Richardson WS, Glasziou R, et al. Evidence-based medicine: how to practice and teach EBM. 3rd edn Edinburgh: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Higgins JPT, Green S. eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.0.1 [updated September 2008] Cochrane Collaboration 2008. http://www.cochrane-handbook.org (accessed 4 Mar 2014) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cochrane Collaboration. About Cochrane Reviews. http://www.cochrane.org/cochrane-reviews (accessed 4 Mar 2014)

- 7.Laupacis A, Straus S. Systematic reviews: time to address clinical and policy relevance as well as methodological rigor. Ann Intern Med 2007;147:273–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Vito C, Nobile CG, Furnari G, et al. Physicians’ knowledge, attitudes and professional use of RCTs and meta-analyses: a cross-sectional survey. Eur J Public Health 2009;19:297–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ely JW, Osheroff JA, Ebell MH, et al. Obstacles to answering doctors’ questions about patient care with evidence: qualitative study. BMJ 2002;324:710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ely JW, Osheroff JA, Chambliss ML, et al. Answering physicians’ clinical questions: obstacles and potential solutions. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2005;12:217–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fozi K, Teng CL, Krishnan R, et al. A study of clinical questions in primary care. Med J Malaysia 2000;55:486–92 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D'Alessandro DM, Kreiter CD, Peterson MW. An evaluation of information seeking behaviors of general pediatricians. Pediatrics 2004;113:64–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coumou HC, Meijman FJ. How do primary care physicians seek answers to clinical questions? A literature review. J Med Libr Assoc 2006;94:55–60 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andrews JE, Pearce KA, Ireson C, et al. Information-seeking behaviors of practitioners in a primary care practice-based research network (PBRN). J Med Libr Assoc 2005;93:206–12 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grandage KK, Slawson DC, Shaughnessy AF. When less is more: a practical approach to searching for evidence-based answers. J Med Libr Assoc 2002;90:298–304 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones TH, Hanney S, Buxton MJ. The role of the national general medical journal: surveys of which journals UK clinicians read to inform their clinical practice. Med Clin (Barc) 2008;131(5 Suppl):30–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prorok JC, Iserman EC, Wilczynski NL, et al. The quality, breadth, and timeliness of content updating vary substantially for 10 online medical texts: an analytic survey. J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65:1289–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perrier L, Persaud N, Ko A, et al. Development of two shortened systematic review formats for clinicians. Implement Sci 2013;8:68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. HHS Web Communications and New Media Division. http://www.usability.gov (accessed 4 Mar 2014) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Pawson R, Tilley N. Realistic evaluation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhaskar R. A realist theory of science. Leeds: Leeds Books, 1975 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Collier A. Critical realism: an introduction to Roy Bhaskar's philosophy. London: Verso, 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miles MB, Huberman M. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patton MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Creswell JW. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wainwright D. Can sociological research be qualitative, critical and valid? The Qualitative Report [Online] 1997;3 http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/QR3-2/wain.html (accessed 4 Mar 2014) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Biernacki P, Waldorf D. Snowball sampling: problems and techniques of chain referral sampling. Sociol Meth Res 1981;10:141–63 [Google Scholar]

- 28.MySQL. Mathematical functions. http://dev.mysql.com/doc/refman/5.0/en/mathematical-functions.html#function_rand (accessed 4 Mar 2014)

- 29.Morgan DL. Practical strategies for combining qualitative and quantitative methods: applications to health research. Qual Health Res 1998;8:362–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus groups. A practical guide for applied research. 3rd edn Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burnard P. A method of analysing interview transcripts in qualitative research. Nurse Educ Today 1991;11:461–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005;15:1277–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kushniruk AW, Triola MM, Borycki EM, et al. Technology induced error and usability: the relationship between usability problems and prescription errors when using a handheld application. Int J Med Inform 2005;74(7-8):519–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs 2008;62:107–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lincoln Y, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, 1985 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nelson AM. Addressing the threat of evidence-based practice to qualitative inquiry though increasing attention to quality: a discussion paper. Int J Nurs Stud 2008;45:316–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mays N, Pope C. Qualitative research in health care. Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ 2000;320:50–2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Opiyo N, Shepperd S, Musila N, et al. Comparison of alternative evidence summary and presentation formats in clinical guideline development: a mixed-method study. PLoS One 2013;8:e55067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cochrane Collaboration. About Systematic Reviews and Protocols. http://www.thecochranelibrary.com/view/0/AboutCochraneSystematicReviews.html (accessed 4 Mar 2014)

- 40.Glasziou P, Chalmers I, Altman DG, et al. Taking healthcare interventions from trial to practice. BMJ 2010;341:c3852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oxman AD, Schünemann HJ, Fretheim A. Improving the use of research evidence in guideline development: 8. Synthesis and presentation of evidence. Health Res Policy Syst 2006;4:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.