Abstract

Context and Background:

Dose sparing action of one adjuvant for another in regional anesthesia.

Aims and Objectives:

To evaluate and compare the clonidine-ropivacaine combination with fentanyl-ropivacaine in epidural anesthesia and also to find out whether addition of clonidine can reduce the dose of fentanyl in epidural anesthesia.

Materials and Methods:

60 patients of ASA grade I and II between the ages of 21 and 55 years, who underwent lower abdominal surgeries, were included randomly into three clinically controlled study groups comprising 20 patients in each. They were administered epidural anesthesia with ropivacaine-clonidine (RC), ropivacaine-fentanyl (RF) or ropivacaine-fentanyl-clonidine (RCF). Per-op and post-op block characteristics as well as hemodynamic parameters were observed and recorded. Statistical data were compiled and analyzed using non-parametric tests and P<0.05 was considered as significant value.

Results:

The demographic profile of the patients in all the three groups was similar as were the various block characteristics. The reduction of clonidine and fentanyl in the RCF group did not make any significant difference (P>0.05) in the analgesic properties of drug combination and hemodynamic parameters as compared to RC and RF groups. However, there was significant reduction of incidence of side effects in the RCF group (P<0.05) and it resulted in increased patient comfort.

Conclusions:

The analgesic properties of the clonidine and fentanyl when used as adjuvant to ropivacaine in epidural anesthesia are almost comparable and both can be used in combination at lower dosages without impairing the pharmacodynamic profile of the drugs as well as with a significant reduction in side effects.

Keywords: Clonidine, epidural anesthesia, fentanyl, lower abdominal surgery, ropivacaine

INTRODUCTION

Feeling of pain is one of the most important emotional determinants which dominate the perception of patients who undergo the surgical procedures. The thoughts of pain create a lot of unknown fears, anxiety and stress in the minds of such patients despite administration of adequate premedication. Even the post-op period can acquire the dimensions of a nightmare once a patient starts experiencing the agony of excruciating pain if not given proper attention. Epidural anesthesia and analgesia is widely regarded as a boon for such patients as it can provide a relief from pain for a longer duration and the facility of further top-ups and continuous infusion of the analgesic drugs through epidural catheter thus provides an uneventful and smooth recovery. Epidural bupivacaine had been used extensively in the past for providing adequate post-op pain relief in patients undergoing lower abdominal surgeries. However, in recent years, ropivacaine has increasingly replaced bupivacaine for the said purpose because of its similar analgesic properties, lesser motor blockade and decreased propensity of cardiotoxicity.[1] Though a slightly larger dose of ropivacaine is required as compared to bupivacaine to achieve the analgesic and anesthetic effects, the addition of an adjuvant can decrease the dose of ropivacaine required, thereby eliminating quite a few side effects associated with larger doses of ropivacaine.[2,3]

Opioids, given by epidural route to relieve post-op pain, may provide adequate analgesia when given in low doses, but can also cause mental confusion, somnolence, nausea and vomiting, itching and respiratory depression when given in high doses.[4,5] Local anesthetic and opioid combination was shown to be more effective in epidural analgesia for post-op pain as their effects started rapidly and lasted longer when compared with local anesthetics given alone.[6] Epidural fentanyl has been widely used in neuraxial blockades as a better alternative to morphine as far as opioid-induced complications and side effects are concerned. The main site of action of fentanyl is the substantia gelatinosa in the dorsal horn of spinal cord, where it blocks the neural fibers carrying pain impulses both at pre-synaptic and post synaptic levels.[7] As fentanyl has no effect on sympathetic and motor neurons, it has advantages over local anesthetics. However, when it is used alone, analgesia will not be enough and overdosing is needed, and side effects like itching, nausea, vomiting and urinary retention are observed. Addition of opioid to local anesthetics gives the opportunity to use more diluted local anesthetic solutions for better analgesia, and reduces systemic toxicity risk and motor block incidence of local anesthetics.[8]

The addition of an adjuvant has further enhanced the effectiveness of these local anesthetics as they not only help in intensifying and prolonging the blockade effect but also help in the reduction of the dose of local anesthetics. Clonidine is a partial alpha-2 adrenergic agonist that has a variety of different actions including antihypertensive effects as well as the ability to potentiate the effects of local anesthetics. It has been used as an adjuvant to epidural local anesthetics and opioids to improve the quality of analgesia after major abdominal surgeries.[9,10] It can provide pain relief by an opioid independent mechanism as it directly stimulates pre- and postsynaptic 2-adrenoceptors in the dorsal horn gray matter of the spinal cord, thereby inhibiting the release of nociceptive neurotransmitters.[11] Though clonidine provides intense and long lasting analgesia, these effects are inadequate for surgical anesthesia. Hence, clonidine has been used as an adjunct only to local anesthetics. At low doses, epidural clonidine improves the quality of anesthesia, reduces the dose requirement of the anesthetic agent and provides a more stable cardiovascular course during anesthesia.[12] Though at higher doses, it may further reduce the dose of local anesthetic and prolong the analgesic duration, but at the same time can exert its toxic effects resulting in profound hypotension, bradycardia and deep sedation.[13]

Keeping all these pharmacological interactions in consideration, we planned a prospective, randomized, double-blind, clinically controlled trial in our institute. We used a mixture of fentanyl and clonidine as an adjuvant to ropivacaine in epidural block to see whether addition of alpha-2 agonist can help in dose sparing of an opioid while preserving the analgesic quality at the same time.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The present study was approved by the ethical committee of the institution and a written consent was taken from the patients after explaining to them in detail about the implications of the anesthetic and the surgical procedure. Inclusion criteria comprised 60 patients of ASA grade I and II between the ages of 21 and 55 years, who underwent lower abdominal surgeries (open hernia repair). The patients with hematological disease, bleeding or coagulation test abnormalities, psychiatric diseases, diabetes, history of drug abuse and allergy to local anesthetics of the amide type were excluded from the study.

Patients were assigned to one of the following three treatment groups in a double-blinded fashion based on a computer-generated random numbers table: ropivacaine + clonidine (RC), ropivacaine + fentanyl (RF), or ropivacaine + fentanyl + clonidine (RFC). All the patients were administered premedication a night before and on the morning of the surgery which comprised tablet ranitidine 150 mg and tablet alprazolam 0.25 mg. The patients were explained about the sequence of anesthetic procedure in the pre-op room and a good IV access was secured. Thereafter, the patients were shifted to the operation theater and all monitoring devices were attached which included devices measuring heart rate (HR), ECG, SpO2, non invasive blood pressure (NIBP) and respiratory rate. Baseline hemodynamic parameters, respiratory rate, ECG and SpO2 were recorded. The anesthesia technician who prepared the syringes was given a written set of guidelines about the drug preparation and he was unaware of the operation theater team and the patients. Patients were administered epidural block in a sitting position with an 18-gauge Touhy needle and epidural space was localized and confirmed by loss of resistance to saline technique. Epidural catheter was secured 3–5 cm into the epidural space and confirmation for correct placement of the catheter was done by injecting 3 ml of 2% lignocaine HCl solution containing adrenaline 1:200,000.

After 4–6 minutes of test dose, patients in group RC received 20 ml of 0.75% ropivacaine and 75 μg of clonidine. Group RF patients were administered 20 ml solution of 0.75% ropivacaine and 75 μg of fentanyl, while group RCF patients received 20 ml of 0.75% ropivacaine, 37.5 μg of clonidine and 37.5 μg of fentanyl. Surgical procedures were initiated only after the establishment of adequate surgical anesthetic effect with minimum level up to T6-7 dermatome.

The bilateral pin-prick method was used to evaluate and check the sensory level while a modified Bromage scale (0 < no block, 1 < inability to raise extended leg, 2 < inability to flex knee and 3 < inability to flex ankle and foot) was used to measure the motor blockade effect at 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 and 30 minute intervals after the epidural administration of the drugs. The following block characteristics were observed and recorded: initial period of onset of analgesia, the highest dermatomal level of sensory analgesia, the complete establishment of motor blockade, the time to two segment regression of analgesic level from T6 dermatome, regression of analgesic level to L5 dermatome and time to complete recovery.

Hemodynamic parameters, which included HR, ECG, mean arterial pressure (MAP), SpO2 and respiratory rate, were monitored continuously. Initial bolus dose timing was assumed to be the baseline time. Recordings were made every 5 minutes until 30 minutes and at 10-minute intervals, and thereafter up to 60 minutes and then at 15-minute intervals for the next hour and finally at 30 minutes in the third hour. Hypotension (defined as systolic arterial pressure falling more than 20% mm Hg) was treated with inj. mephenteramine 3–6 mg in bolus doses and HR<55 beats/min was treated with 0.3 mg of inj. atropine. Intravenous fluids were given as per the body weight and operative loss requirement, with no patient requiring blood transfusion. The patients were given supplementary O2 with the help of venturi mask. During the surgical procedure, any adverse event like anxiety, nausea, vomiting, pruritis, shivering, bradycardia, or hypotension was recorded. Nausea and vomiting were treated with 4–6 mg of i.v. ondansetron.

During and at the end of surgery, the vitals were recorded in the recovery room also at 1, 5, 10, 20 and 30 minute interval. Sedation was evaluated by five-point scale (1 < wide awake; 2 < drowsy; 3 < dozing; 4 < mostly sleeping; 5 < awakening only when aroused). The onset of pain was managed by top-up doses of 8 ml of 0.2% ropivacaine and 50 μg of clonidine in RC group while 50 μg fentanyl was added to the same volume of ropivacaine in RF group. The patients in RCF group received 25 μg each of clonidine and fentanyl along with 8 ml of 0.2% ropivacaine during the first top-up dose. Later on, all the patients received 8 ml of 0.2% ropivacaine for relief of post-op pain.

Comparability of the groups was analyzed with analysis of variance test (ANOVA). Student's two tailed “t” test and chi square test were applied to analyze the parametric data (maternal hemodynamic parameters and block characteristics). For all statistical analysis, the value of P<0.05 was considered as significant.

RESULTS

Sixty patients were enrolled in this study and their data were eligible and were processed for statistical analysis.

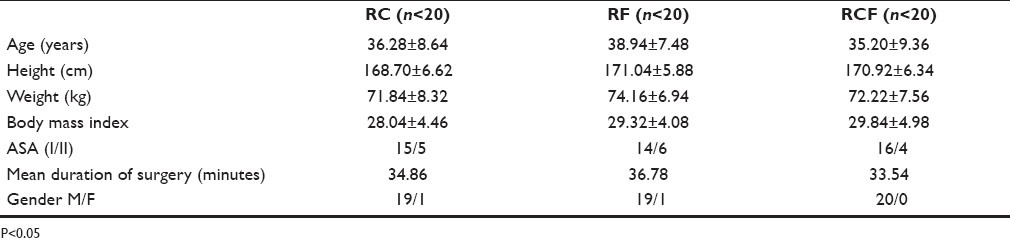

The three groups were comparable with regard to demographic data as shown in table 1. There was no statistically significant variation between the three groups with regard to age, weight, height and body mass index (P>0.05). Duration of surgery was comparable in both the groups and did not show any significant variation.

Table 1.

Comparison of demographic profile of the RC, RF and RCF groups

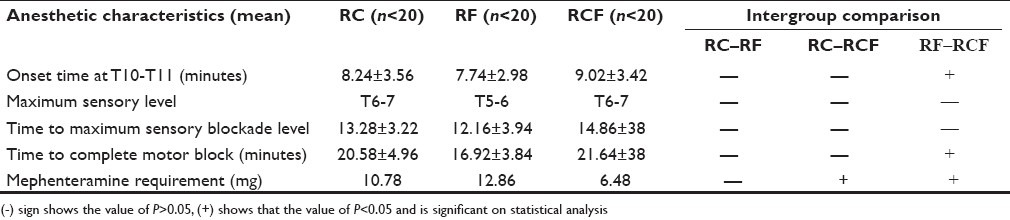

Onset of anesthesia was faster in group RF as compared to group RC and RCF as shown in table 2. However, once sensory level was established at T6-T7 level, there was no noticeable difference in sensory anesthesia in any of the three groups throughout the surgical procedure. The establishment of complete motor blockade was earlier in the RF group which was statistically significant, when compared to RCF (P<0.05). The hypotension was treated with incremental doses of mephenteramine 3 mg bolus doses, but the total dose did not cross 18 mg in any of the groups. Mephenteramine was used almost 40% lower in the RCF group which was statistically significant (P<0.05) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Comparison of initial block characteristics in RC, RF and RCF groups

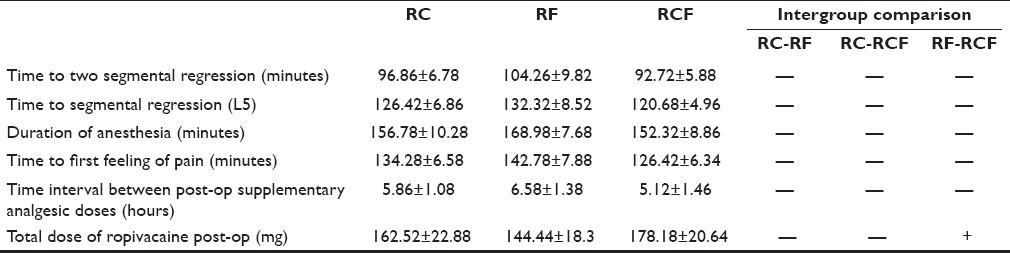

As is clearly evident from the table 3, the regression of block height was slightly prolonged in RF group while the total duration of anesthesia and time for supplementary analgesic doses was prolonged in RF group, which was statistically nonsignificant on analysis (P>0.05). The mean total dose of ropivacaine consumed post-op was highest among the patients of RCF group, which on statistical comparison turned out to be a significant value when compared to RCF group (P<0.05).

Table 3.

Comparison of per-op and post-op block characteristics in RC, RF and RCF groups

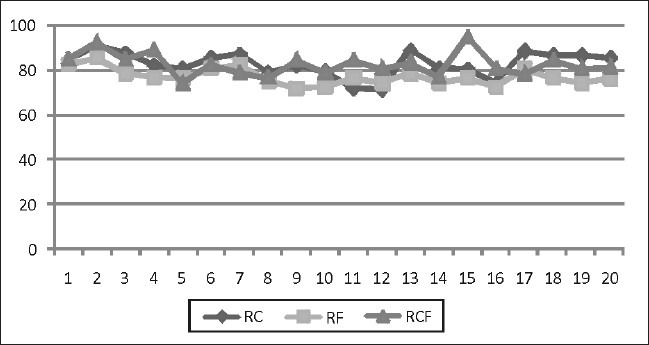

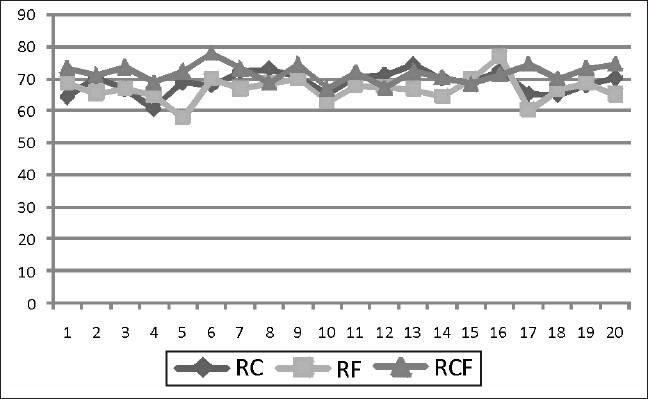

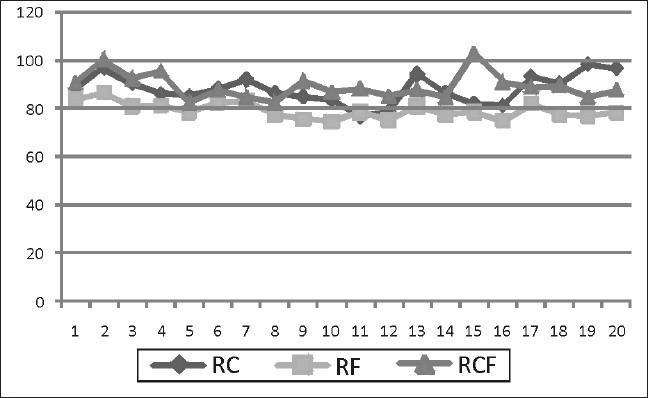

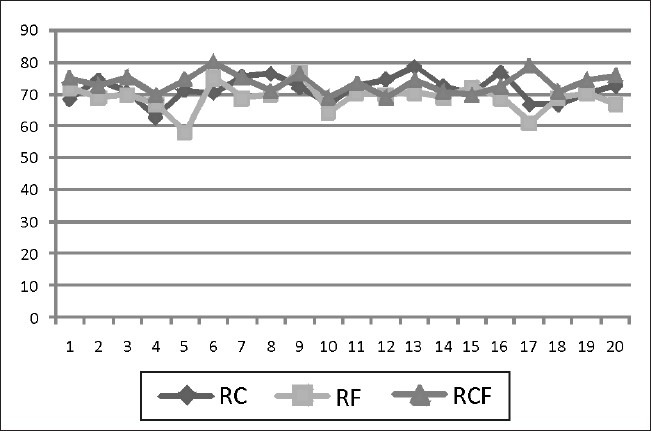

Table 4 and the Figures 1–4 shows that MAP and mean HR were comparable in all the three groups during the entire procedure as well as post-op, which was a non-significant value on statistical comparison (P>0.05). Similarly, pulse oximetry trends did not show any significant variation in patients of all the three groups.

Table 4.

Comparison of vital parameters in patients of RC, RF and RCF groups

Figure 1.

Intra-op MAP comparison in all the groups

Figure 4.

Showing the post-op HR comparison in all the groups

Figure 2.

Post-op MAP comparison in all the groups

Figure 3.

Intra-op HR comparison in all the groups

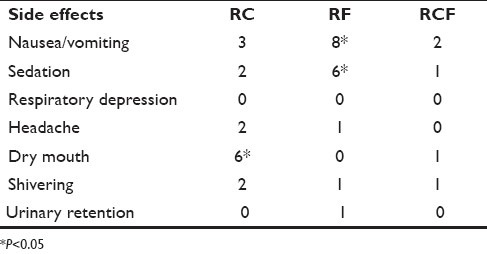

Table 5 outlines the various side effects observed during the entire study with all the three drug groups. In the RF group, 40% of the patients experienced nausea/vomiting as compared to 15% in group RC and 10% in RCF, which was statistically significant (P<0.05). Similarly, we observed sedation in 30% of the patients in group RF as compared to 10% in RC group and 5% in RCF group, which again was a statistically significant value on intergroup comparison (P<0.05).The incidence of dry mouth was statistically higher to significant values in group RC (P<0.05). The incidence of other side effects like shivering, headache, urinary retention and respiratory depression was almost comparable and statistically nonsignificant.

Table 5.

Incidence of side effects in patients of all the three groups

DISCUSSION

The quest for optimal dose finding of either an opioid or alpha-2 blocker as an adjuvant in regional anesthesia is never ending but there are hardly any studies which have tried to compare the potential benefits of either the two combinations or tried to evaluate the “synergistic” effect of these two in lower concentration.[14–16] Ours is the first study to evaluate rigorously the effects of clonidine on dose reduction concentration of fentanyl, when administered as an adjuvant to ropivacaine in epidural anesthesia for lower abdominal surgeries. Fentanyl has almost completely replaced the traditional opioid morphine as an adjuvant in regional anesthesia, but side effects like nausea and vomiting still persist to an alarming extent of 28–52%, when used in optimal dose, which is quite discomforting for the patients and defeats the purpose of providing a smooth uneventful recovery.[5,6,17] The analgesic effects of the ropivacaine–clonidine combination are equivalent to those of the ropivacaine–fentanyl. The results of the present study demonstrate that it is possible to decrease the unwanted side effects of epidural fentanyl by reducing the dose of fentanyl and adding an equivalent dose of clonidine to the epidural solution, and that too without impairing the analgesic effect. The reduction in opioid requirement does have a significant effect on reduction of incidence of nausea and vomiting, beneficial effects on respiratory functions as well as reduction of other opioid-related side effects.[5,6] We did not observe a single case of respiratory depression in our study and this probably may be due to smaller dose of fentanyl we used in our study.

Alpha-adrenergic agonists produce pain relief through an opioid independent mechanism and may be alternatives to opioid for combination with local anesthetics for analgesia during surgery.[18,19] Based on the pharmacokinetic properties like molecular weight, lipid solubility and cerebrospinal fluid level, clonidine can be expected to exert similar onset of its analgesic effect and duration of analgesia as compared to fentanyl, but analgesic effect of fentanyl starts faster and lasts longer.[20]

The attempts made earlier for dose determination concluded that 75 μg of clonidine is the optimal epidural dose when added to bupivacaine for analgesia, as smaller doses were not serving the purposes of adequate analgesia while larger doses were associated with bradycardia, hypotension, sedation and other side effects.[21] Therefore, we administered single clonidine dose of 75 μg for operative purpose while top-up doses of 50 μg clonidine were administered with 0.2% ropivacaine for the post-op pain relief.

The initial block characteristics in the present study did not show much difference among the three study groups. The onset time and establishment of block was slightly shorter in fentanyl group but clinically nonsignificant, which is almost comparable to other studies.[15] The mephenteramine requirement was significantly lesser in the group receiving a mixture of clonidine and fentanyl, which clearly proves that doses of both fentanyl and clonidine can be reduced, thereby eliminating the incidences of complications and that too without impairing the analgesia. Similarly, peri-op and post-op block characteristics followed the same pattern as initial block effects, which correlate very well with the findings of other studies.[18] The total post-op dose consumption of ropivacaine was significantly lesser in RF group as compared to RCF group, which again helped us to draw the conclusions that epidural doses of clonidine and fentanyl can be reduced in combination and still be able to produce a slightly lesser but acceptable degree of anesthetic and analgesic effects with a very low incidence of side effects. The stable hemodynamic parameters throughout the surgical procedure as well as post-op in all the three groups do point toward the equal effectiveness of all the three combination of drugs in exerting minimal cardiac effects. Both fentanyl and clonidine, when used alone in optimal doses in epidural route with ropivacaine, do produce an array of side effects which include sedation, nausea/vomiting, dry mouth, etc. The side effects become almost nonexistent when these are used in combination with their dose reduced to half of the optimal dose. As a result, the patient in group RCF felt more comfortable in the post-op period and described the anesthesia as the most pleasing experience.

CONCLUSIONS

The study helped us to conclude the established facts about the epidural usage of clonidine and fentanyl, when added as an adjuvant to ropivacaine. Though both the drugs have side effects when used in epidural route in optimal doses, the spectrum of side effects of clonidine is much narrower than that of fentanyl.

Combination of clonidine with fentanyl does allow the reduction of individual doses of these drugs through epidural route.

The combination of clonidine and fentanyl in half than the optimal doses has almost similar pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile when used with ropivacaine in epidural anesthesia.

The power analysis of the study was estimated at 80%.

Therefore, we recommend that the combination of fentanyl and clonidine can be safely used with ropivacaine and that too in half the doses as they have got a synergistic adjuvant effect.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Katz JA, Bridenbaugh PO, Knarr DC, Helton SH, Denson DD. Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of epidural ropivacaine in humans. Anesth Analg. 1990;70:16–21. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199001000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Landau R, Schiffer E, Morales M, Savoldelli G, Kern C. The dose-sparing effect of clonidine added to ropivacaine for labour epidural analgesia. Anesth Analg. 2002;95:729–34. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200209000-00036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Santos AC, Arthur GR, Pedersen H, Morishima HO, Finster M, Covino BG. Systemic toxicity of ropivacaine during ovine pregnancy. Anesthesiology. 1991;75:137–41. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199107000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rockemann MG, Seeling W, Brinkmann A, Goertz AW, Hauber N, Junge J, et al. Analgesic and hemodynamic effects of epidural clonidine, clonidine/morphine and morphine after pancreatic surgery: A double-blind study. Anesth Analg. 1995;80:869–74. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199505000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gedney JA, Liu EH. Side effects of epidural infusions of opioid bupivacaine mixtures. Anesthesia. 1998;53:1148–55. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.1998.00636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ozalp G, Guner F, Kuru N, Kadiogullari N. Postoperative patient-controlled epidural analgesia with opioid bupivacaine mixtures. Can J Anaesth. 1998;45:938–42. doi: 10.1007/BF03012300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cousins MJ, Mather LE. Intrathecal and epidural administration of opioids. Anesthesiology. 1984;61:276–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turner G, Scott DA. A comparison of epidural ropivacaine infusion alone and with three different concentration of fentanyl for 72 hours of postoperative analgesia following major abdominal surgery. Reg Anesth. 1998;23:A39. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Motsch J, Graber E, Ludwig K. Addition of clonidine enhances postoperative analgesia from epidural morphine: A double-blind study. Anesthesiology. 1990;73:1067–73. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199012000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forster JG, Rosenberg PH. Small dose of clonidine mixed with low-dose ropivacaine and fentanyl for epidural analgesia after total knee arthroplasty. Br J Anaesth. 2004;93:670–7. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeh259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eisenach JC, De Kock M, Klimscha W. Alpha2-adrenergic agonists for Regional Anesthesia: A Clinical Review of Clonidine (1984-1995) Anesthesiology. 1996;85:655–74. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199609000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Acalovschi I, Bodolea C, Manoiu C. Spinal anesthesia with meperidine, effects of added -adrenergic agonists: Epinephrine versus clonidine. Anesth Analg. 1997;84:1333–9. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199706000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maze M, Tranquilli W. Alpha-2 adrenoceptor agonists: Defining the role in clinical anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 1991;74:581–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeKock M, Wiederkher P, Laghmiche A, Scholtes JL. Epidural clonidine used as the sole analgesic agent during and after abdominal surgery: A dose-response study. Anesthesiology. 1997;86:285–92. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199702000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Curatolo M, Schnider TW, Petersen-Felix S, Weiss S, Signer C, Scaramozzino P, et al. A direct search procedure to optimize combinations of epidural bupivacaine, fentanyl, and clonidine for postoperative analgesia. Anesthesiology. 2000;92:325–37. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200002000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Negri P, Ivani G, Visconti C, De Vivo P, Lonnqvist PA. The dose-response relationship for clonidine added to a postoperative continuous epidural infusion of ropivacaine in children. Anesth Analg. 2001;93:71–6. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200107000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper DW, Turner G. Patient-controlled extradural analgesia to compare bupivacaine, fentanyl and bupivacaine with fentanyl in the treatment of postoperative pain. Br J Anaesth. 1993;70:503–7. doi: 10.1093/bja/70.5.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kizilarslan S, Kuvaki B, Onat U, Sagiroglu E. Epidural fentanyl-bupivacaine compared with clonidine-bupivacaine for analgesia in labour. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2000;17:692–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2346.2000.00740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dobrydnjov I, Axelsson K, Gupta A, Lundin A, Holmström B, Granath B. Improved analgesia with clonidine when added to local anesthetic during combined spinal-epidural anesthesia for hip arthroplasty: A double blind, randomized and placebo-controlled study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scan. 2005;49:538–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2005.00638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Castro MI, Eisenach JC. Pharmacokinetics and dynamics of intravenous, intrathecal and epidural clonidine in sheep. Anesthesiology. 1989;71:418–25. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198909000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brichant JF, Bonhomme V, Mikulski M, Bajwa SS, Bajwa SK, Kaur J, et al. Admixture of clonidine to epidural bupivacaine for analgesia during labor: Effect of varying clonidine doses. Anesthesiology. 1994;81:A1136. [Google Scholar]