Abstract

Context:

Celphos poisoning is one the most common and lethal poisonings with no antidote available till now.

Aims:

To evaluate the effectiveness of new treatment regimens and interventions in reduction of mortality from the fatal effects of celphos poisoning.

Settings and Design:

A profile of 33 patients, who got admitted in Intensive Care Unit (ICU) of our institute with alleged intake of celphos pellets, was studied.

Materials and Methods:

In all the 33 patients with alleged celphos poisoning, extensive gastric lavage was done with a mixture of coconut oil and sodium bicarbonate solution. Strict monitoring, both invasive and non-invasive, was done and symptomatic/supportive treatment was carried out on a patient to patient basis.

Statistical Analysis:

At the end of the study, all the data were compiled systematically and statistical analysis was carried out using the non-parametric tests and value of P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results:

Majority of the patients out of the total 33 were young with mean age of 21.86±4.92 and had good educational level. Most of the patients presented clinically with cardiovascular signs and symptoms (58%), followed by respiratory distress (15%) and little higher incidence of multi-organ symptomatology (18%). The mean stay of the patients in ICU was 5.84±1.86 days and the survival rate was 42%.

Conclusions:

With the treatment regimen we have formulated, we were able to save 42% of our patients and recommend the use of this regimen by all the intensivists and physicians.

Keywords: Aluminum phosphide, celphos, coconut oil, magnesium sulfate, phosphide poisoning

INTRODUCTION

Aluminum phosphide (AlP) is used to preserve grains all over the world. It is also known as celphos and is one of the most dreaded poisons one can ever encounter in toxicology. The salt is usually available in tablet and pellet forms. AlP poisoning is common in all parts of the world, but is found more commonly in developing countries like India and is often implicated in accidental and suicidal poisonings in India.[1–3] The fatal dose is around 0.5 g and acute poisoning with these compounds may be direct due to ingestion of the salts or indirect from accidental inhalation of phosphine generated during their approved use. Many lives have been lost in the last three decades, especially among the young rural population of northern India. It is not just limited to the agricultural society, but the incidence is increasing in the urban families also. Previously, the laws and legislations were not that strict and it was easily available on the counter; but in the last few years stricter norms have reduced its easy availability, even though they are still not enough to reduce the suicidal rate due to its consumption, which traumatizes so many families. It is a highly toxic compound that releases phosphine gas on contact with moist surfaces and patients can present clinically with gastrointestinal (GI) hemorrhage, arrhythmias, shock, renal and hepatic failure, central nervous system disturbances and ultimately leading to death in almost 100% of cases.[1,3,4] Most patients who survived had either taken a very small amount or the tablet had been exposed to air, thus rendering it non-toxic. Patients remain mentally clear till cerebral anoxia due to shock supervenes resulting in drowsiness, delirium and coma. Several ECG changes ranging from ST segment elevation/depression, PR and QRS interval prolongation, complete heart block to ectopics and fibrillation have been observed. Reversible myocardial injury has also been reported.[3,5,6]

The breath of patients who have ingested AlP has a characteristic garlic-like odor. Conformation of diagnosis is based on the patient's history and a positive result (blackening) on tests of the patient's breath with paper moistened with fresh silver nitrate solution or by chemical analysis of blood or gastric acid for phosphine.

Celphos poisoning has always been a big headache and menace for the intensivists throughout the world probably due to nonavailability of its antidote and 100% mortality which does not encourage the physicians to try whole heartedly to salvage the patients. The literature is full of different drugs and trials to counter its irreversible toxic effects, but hardly with any concrete success. Keeping all these facts and figures in consideration, we undertook a retrospective analysis at the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) of our institute, whereby we tried to treat the patients with mixture of coconut oil and sodium bicarbonate used for gastric lavage, mixed in equal proportions, to make lavage solution of 100 ml. The main aim was to find whether the regimen we devised is of any help in saving the precious lives of the people who in a rage and fury consume this deadly poison, the antidote for which is still not in the sight. The objective was to see the effectiveness of this medication combo to decrease the very high the mortality and morbidity as result of consumption of this poison.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The approval of Ethics Committee of the institute had already been taken for all poisoning cases and especially for the treatment of celphos poisoning. The reason for pre-approval for celphos poisoning was that in such cases mortality is 100% and no time should be lost in resuscitating such patients. Thirty-three patients got admitted to ICU of our institute over the last 3.5-year period with an alleged history of intake of celphos (AlP) poisoning. Most of the patients were young and either unmarried or newly married. Most of them had features of cardiogenic shock, hypotension and arrhythmias, while few got admitted with respiratory distress and rest of them had multitude of symptoms related to different organ systems.

On admission to ICU, the patients were made comfortable on the bed, monitoring gadgets were attached for Heart Rate (HR), Non-Invasive Blood Pressure (NIBP), ECG, Pulse Oximetry (SpO2) and End-tidal carbon dioxide (EtCO2) and Ryle's tube was inserted through nasal route. The patients who were grossly unstable hemodynamically or had respiratory distress were induced with injection ketamine 2 mg/kg body weight and injection vecuronium bromide 0.1 mg/kg body weight. Endotracheal intubation was done with appropriate size cuffed endotracheal tube and patients were put on mechanical ventilation. Gastric lavage was initiated with aliquots of 50 ml of coconut oil and 50 ml of sodium bicarbonate solution and continued for the next half an hour, with simultaneous aspiration being done after every 2–3 minutes through Ryle's tube. Coconut oil was just heated to lukewarm temperature so as to make a miscible solution with sodium bicarbonate. The procedure of gastric lavage was usually done 12–15 times in the first hour. Initial 30 ml lavage was sent to forensic laboratory for toxicological analysis.

An intravenous access through internal jugular vein was established for central venous pressure monitoring as well as for guiding the fluid therapy in majority of patients who had presented with cardiovascular instability, respiratory distress and renal failure. In a few patients who had severe cardiogenic shock, an arterial line was also secured through radial/dorsalis pedis artery for observing beat to beat variation of HR and BP. Symptomatic treatment was initiated on a patient to patient basis. Magnesium sulfate, dopamine, dobutamine, amiodarone infusions and other appropriate intravenous drugs were given depending on the patient's clinical presentation and symptomatology, as well as arrhythmias and blood pressure variations. Urine output was monitored through Foley's catheter attached to urobag. Patients who required mechanical ventilation were kept sedated with injection midazolam and paralyzed with injection vecuronium. During this period, strict and vigil monitoring of all vital parameters was done and treatment regimens were titrated according to the clinical condition of the patients. Gastric lavage was again performed after 1 hour of admission with the same solution for next half an hour.

After admission in the ICU, all the baseline routine and specific investigations were carried out including regular arterial blood gas analysis (ABG). Soda bicarbonate was given empirically to all patients in a dose of 1–1.5 mEq/kg body weight and further adjusted for correction of metabolic acidosis as per ABG reports. At the end of the study period, all the data were arranged systematically and were subjected to statistical analysis using non-parametric tests. Value of P<0.05 was taken as significant value.

RESULTS

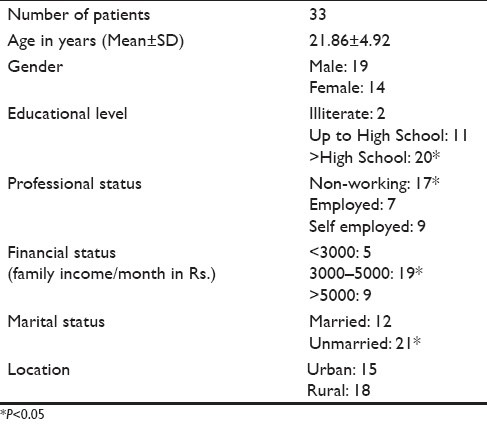

In the last 3.5 years, 673 patients had got admitted in ICU for one indication or the other, out of whom 33 got admitted with an alleged history of celphos intake. The demographic profile of these patients is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic profile and the patient characteristics

The age of 33 patients who got admitted in ICU ranged from 18 to 48 years, with a mean and standard deviation of 21.86±4.92. There was not much significant difference on the gender basis as 19 males and 14 females were admitted with celphos consumption. The incidence of poisoning was surprisingly high with a significant proportion in the more educated class and who were non-working (P<0.05). The incidence was more in the families of moderate income, especially among the unmarried young members, which was statistically significant on analysis. The incidence of poisoning was evenly distributed among the rural and urban population and was considered to be a non-significant factor (P>0.05) [Table 2].

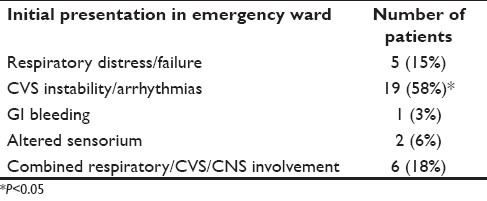

Table 2.

Clinical presentation of the patients in ICU

The maximum number of patients presented clinically with cardiovascular instability, either in the form of hypotension or arrhythmias (58%), which was clinically quite significant (P<0.05). Also, 15% of the patients presented with respiratory distress alone, while 18 of the patients had combined symptoms related to respiratory, CVS or CNS. Rest of the patients got admitted with other symptoms such as GI bleed or altered sensorium [Table 3].

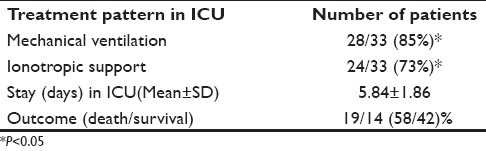

Table 3.

Treatment pattern in ICU

Out of the 33 patients, 28 required mechanical ventilation and 73% of the patients required ionotropic support for maintaining stable hemodynamic parameters. The mean stay in ICU varied from 2 to 11 days, with a mean stay of 5.84 days with an SD of 1.86. Also, 42% of the patients were saved which is quite significant, but the rest (58%) succumbed to their poisonings [Table 4].

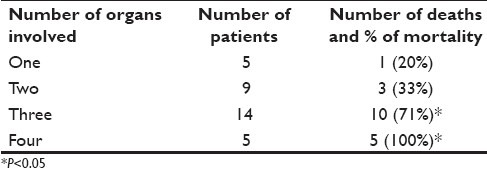

Table 4.

Number of organ systems affected

The mortality rate varied from 20 to 100% and the mortality increased with progressive involvement of the number of organs. As shown in Table 4, the mortality reaches 100% if four or more organs are involved, which is statistically significant (P<0.05).

DISCUSSION

Celphos is formulated as a greenish gray tablet of 3 g, which in the presence of moisture or HCl, releases phosphine:

AlP+3H2O=Al(OH)3+PH3

AlP+3HCl=AlC13+PH3

The residue, Al(OH)3 is non-toxic

AlP, when ingested, liberates a lot of phosphine (PH3) gas in the stomach, which has a very pungent smell. Phosphine gas is rapidly absorbed from the gastric mucosa and, once it gains access to bloodstream, it reaches various tissues and at cellular level inhibits the mitochondrial respiratory chain and hence leads to cell necrosis and death. It has been suggested that phosphine leads to non-competitive inhibition of the cytochrome oxidase of mitochondria, blocking the electron transfer chain and oxidative phosphorylation, producing an energy crisis in the cells.[7,8] Recently, Chugh et al. found inhibition of catalase and induction of superoxide dismutase enzymes by phosphine in humans, leading to free radical formation, lipid peroxidation and protein denaturation of cell membrane, ultimately leading to hypoxic cell damage. This has been suggested to inhibit myocardial cellular metabolism and necrosis of the cardiac tissue, resulting in the release of reactive oxygen intermediates.[9] Refractory myocardial depression from AlP toxicity is not uncommon and carries a very high mortality.[4,10] These cardiotoxic effects were quite marked in our patients, as 88% of the patients required ionotropic support. Vascular changes may lead to marked low blood pressure that does not respond well to pressor agents. Cardiotoxicity/toxic chemical myocarditis is manifested as depressed left ventricular ejection fraction, ECG changes varying from ST segment elevation/depression, PR prolongation, broad QRS complexes, and right or left bundle branch block, supraventricular ectopics or fibrillation.[11] Biochemical changes include rise in aspartate transaminase (AST), creatine phosphokinase-MB (CPK-MB) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). Histopathology shows myocytolysis, multiple areas of necrosis and congestion.[12] Hypomagnesemia has been known to cause arrhythmias in AlP poisoning and magnesium supplementation has been suggested as a therapeutic option.[4] The findings of our study do correlate with all the above studies, as most of our patients presented with arrhythmias of varying nature and it proved fatal in majority of the patients who died in our ICU. Majority of our patients were young, unmarried with male gender predominance, and poisoning was quite prevalent in the educated community, both from the rural and urban population, in almost equal proportion. The incidence was equal among working and the non-working population, highlighting the fact that the employment stress is not the only factor but rather it is the social and family factors which drive these people to commit suicide.

Toxicity that occurs after inhalation is characterized by chest tightness, cough and shortness of breath. Severe exposure can cause accumulation of fluid in the lungs, which may have a delayed onset of 72 hours or more after exposure. Children may be more vulnerable because of relatively increased minute ventilation per kilogram and failure to evacuate an area promptly, when exposed. Furthermore, this phosphine gas is eliminated through the lungs; hence, due to high concentration in the respiratory alveoli, it is responsible for direct alveolar damage.[8] Large number of our patients also presented with respiratory distress, either alone or in combination with other organ dysfunction. Five of our patients developed severe pulmonary edema during the initial course of the treatment and we resorted to Bains circuit manual ventilation with 100% oxygen as the patients developed severe hypoxemia which was evident in ABG report. Ventilator was unable to deliver the oxygen due to very high pressures in the pulmonary alveoli. We continued the manual ventilation till the correction of hypoxemia, which almost took 2–3 hours in all the five patients. Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and exudative pleural effusions can develop. Studies in the past have shown increased levels of inflammatory markers (cytokines and interleukins) in ARDS, which increase the capillary permeability. This combined effect of increase in capillary permeability due to global hypoxia and ARDS could be responsible for the exudative effusion seen predominantly in the pleural cavity and not in other serous cavities.[13]

GI symptoms are usually the first to occur after exposure. Symptoms may include nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain and diarrhea. One of our patients, who consumed six tablets of celphos, developed severe gastric bleeding which could not be controlled and ultimately led to the death of the patient within 1 hour. Death due to acute hepatocellular toxicity and fulminant hepatic failure has also been reported in acute poisoning. Blood and protein in the urine, and acute kidney failure due to shock can occur. Analysis of blood gases may reveal combined respiratory and metabolic acidosis. Also, there have been reports of significant hypomagnesemia and hypermagnesemia associated with massive focal myocardial damage.[13,14] Our findings are quite consistent with these facts as the mortality increased with increasing number of organ system involvement. Chronic exposures to very low concentrations may result in anemia, bronchitis, GI disturbances, and visual, speech, and motor disturbances.[9]

Gastric lavage is important in the initial stage. The management principles aim to sustain life with appropriate resuscitation measures until phosphine is excreted from the body. If phosphides have been ingested, do not induce emesis. Gastric lavage with saline or sodium bicarbonate or potassium permanganate (1:1000) has also been recommended by earlier studies.[14] The rationale behind the use of a mixture of soda bicarbonate and coconut oil in our patients is guided by the chemical reaction of AlP with moisture and HCl, liberating phosphine gas which rapidly gets absorbed through gastric mucosa. As the poison itself causes a lot of gastric mucosal damage, it exposes a lot of raw area for phosphine absorption. The mechanism by which coconut oil reduces the toxicity of phosphides is unknown but most probably it forms a protective layer around the gastric mucosa, thereby preventing the absorption of phosphine gas. Secondly, it helps in diluting the HCl and again inhibiting the breakdown of phosphide from the pellet. Soda bicarbonate mainly neutralizes the HCl and thus diminishing the catalytic reaction of phosphide with HCl, thereby inhibiting the release of phosphine.[15]

The main principles of treatment are the following.

Carry out methods to absorb phosphine through GI tract and neutralizing the HCl with soda bicarbonate and coconut oil, as explained earlier.

Reduce organ toxicity with appropriate interventions.

Enhance phosphine excretion, especially through lungs, by increasing the respiratory rate, which becomes easier when the patient is paralyzed, sedated and put on mechanical ventilation. This results in decreasing the basal metabolic rate of body and decreased oxygen requirement, thus compensating the actions of inhibited cytochrome oxidase to some extent.

Phosphine is excreted through urine also. Therefore, adequate hydration and renal perfusion by low-dose dopamine 4–6 μg/kg/minute must be maintained. Diuretics are not useful in the presence of profound shock.

Supportive measures have to be taken.

Suggestions

Certain specific measures can be adopted to reduce the fatal episodes of AlP. These include the following.

Role of hyperbaric oxygen can be studied especially in the background of inhibition of mitochondrial respiratory chain.

The gastroscope can be used to remove the undissolved pellet.

Water should not be used as a lavage agent.

Some highly pungent and nauseating substance may be added to the pellets.

Strict laws and legislations can be made regarding the free sales of the chemical.

Availability of single tablet pack encased in hard plastic material with hard spikes will be helpful.

Social awareness regarding handling of the substance and its lethal consequences is required.

Alternatives to celphos, which are less toxic and fatal, should be manufactured to serve the same purpose.

Lab research should be undertaken extensively to find out its antidote.

CONCLUSIONS

Antidotes for various fatal poisons have been developed over the last three decades, but even now this poison is killing the mankind. Although few lives have been saved here and there, doubt still remains about the nature of poison consumed, the amount of poison consumed, the time interval between consumption and resuscitation and so on. With the treatment regime we have formulated, we were able to save 42% of our patients who had been admitted with a definite history and confirmed lab findings of celphos poisoning. Four of our patients consumed three or more than three tablets of the celphos poison, while five of the patients were brought to the hospital almost more than 4 hours of ingestion of the celphos pellet which we believe led to the increase of mortality rate among our patients. We recommend the use of this regimen by all the intensivists and physicians so as to possibly save the lives of so many patients from this hopeless situation.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siwach SB, Yadav DR, Arora B, Dalal S, Jagdish Acute aluminium phosphide poisoning: An epidemiological, clinical, and histopathological study. J Assoc Physicians India. 1988;36:594–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koley TF. Aluminium phosphide poisoning. Indian J Clin Pract. 1988;9:14–22. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta S, Ahlawat SK. Aluminium phosphide poisoning – A review. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1995;33:19–24. doi: 10.3109/15563659509020211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chugh SN, Arora BB, Malhotra GC. Incidence and outcome of aluminium phosphide poisoning in a hospital study. Indian J Med Res. 1991;94:232–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh UK, Chakraborty B, Prasad R. Aluminium phosphide poisoning: A growing concern in paediatric population. Indian Paediatr. 1997;34:650–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chugh SN, Arora V, Kaur S, Sood AK. Toxicity of exposed aluminium phosphide. J Assoc Physicians India. 1993;41:569–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cherfuka W, Kashi KP, Bond EP. The effect of phosphine on electron transport in mitochondria. Pest Biochem Physiol. 1976;6:65–84. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sudakin DL. Occupational exposure to aluminium phosphide and phosphine gas: A suspected case report and review of the literature. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2005;24:27–33. doi: 10.1191/0960327105ht496oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lall SB, Sinha K, Mittra S, Seth SD. An experimental study on cardio toxicity of aluminium phosphide. Indian J Exp Biol. 1997;35:1060–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bogle RG, Theron P, Brooks P, Dargan PI, Redhead J. Aluminium phosphide poisoning. Emerg Med J. 2006;23:e3. doi: 10.1136/emj.2004.015941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mathur A, Swaroop A, Aggarwal A. ECG changes in aluminium phosphide and organo phosphorus poisoning. Indian Pract. 1999;52:249–52. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karanth S, Nayyar V. Rodenticide-induced Hepatotoxicity. J Assoc Physicians India. 2005;51:316–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suman RL, Savani M. Pleural Effusion – A Rare Complication of Aluminium Phosphide Poisoning. Indian Paediatr. 1999;36:1161–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chugh SN. Aluminium Phosphide in Lall SB, Essentials of Clinical Toxicology. New Delhi: Narosa Publishing House; 1998. pp. 41–6. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shadnia S, Rahimi M, Pajoumand A, Rasouli MH, Abdollahi M. Successful treatment of acute aluminium phosphide poisoning: Possible benefit of coconut oil. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2005;24:215–8. doi: 10.1191/0960327105ht513oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]