Abstract

Background:

The Smile Train is an international charity with an aim to restore satisfactory facial appearance and speech for poor children with cleft abnormalities who would not otherwise be helped. A total of 241 children of cleft lip and palate anomaly, scheduled for surgery under general anesthesia, were studied. Cleft abnormality requires early surgery. Ideally cleft lip in infants should be repaired within the first 6 months of age; and cleft palate, before development of speech, i.e., at the age of 2 years. But in our study, only 27% of children underwent corrective surgery by ideal age of 2 years, which may be due to ignorance, poverty or unawareness about the fact that cleft anomaly can be corrected by surgery.

Context:

Smile Train provides care for poor children with clefts in developing countries. The guidelines were designed to promote safe general anesthesia for cheiloplasty and palatoplasty.

Aims:

Smile Train promotes free surgery for cleft abnormalities to restore satisfactory facial appearance and speech.

Settings and Design:

This was a randomized prospective cohort observational study.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 241 consenting patients of American Society of Anesthesiologt (ASA) I and II aged 6 months to 20 years of either sex, scheduled for elective cheiloplasty and palatoplasty, were studied. Children suffering from anemia, fever, upper respiratory tract infections or any associated congenital anomalies were excluded. Approved guidelines of the Smile Train Medical Advisory Board were observed for general anesthesia and surgery.

Statistical Analysis:

The Student t test was used.

Results:

The infants were anemic and undernourished, and two thirds of the children were male. Only 27% of the children presented for surgery by the ideal age of 2 years.

Conclusions:

Pediatric anesthesia carries a high risk due to congenital anomaly and shared airway, venous access and resuscitation; however, cleft abnormality requires surgery at an early age to make the smiles of affected children more socially acceptable.

Keywords: Cheiloplasty, cleft lip and palate, general anesthesia, palatoplasty

INTRODUCTION

Cleft lip and palate are the commonest craniofacial abnormalities; considered together, they constitute the third most common congenital anomaly that requires surgical correction at an early age. A cleft lip, with or without a cleft palate, occurs in 1 in 600 live births. A cleft palate alone is a separate entity and occurs in 1 in 2,000 live births. The cleft lip (with or without cleft palate) is more common in males, whereas isolated cleft palate is more common in females.

Congenital clefts of upper lip occur because of failure of fusion of the maxillary and the medial and the lateral nasal processes. The cleft can involve the lip, alveolus, hard palate and/or soft palate and can be complete or incomplete, unilateral or bilateral. In addition, associated dental abnormalities may also be seen.

These obvious defects of the upper airway predispose the child to difficulty in swallowing, repeated aspiration and pulmonary infection. Children born with a cleft anomaly are otherwise healthy, but sometimes it may be associated with different syndromes, like Pierre Robin, Treacher Collin and Goldenhar syndromes. The most common nonsyndrome-related abnormalities are umbilical hernias, clubfoot, and limb and ear deformities.

Pathophysiology of cleft lip and palate

Cleft palate is responsible for major physiologic disorders. The pharynx communicates more extensively with the nasal fossae and the oral cavity. The complex mechanisms of swallowing, breathing, hearing (through the Eustachian tube) and speech are therefore impaired. The presence of cleft lip and palate in a neonate results in feeding difficulties. Breast feeding is improbable and bottle feeding is difficult. Nasal septation between food and air is absent, creating a nonphysiologic mixing chamber in the nasopharynx. Secondary defects of tooth development, growth of the ala nasi and psychological problems may be considerable as this youngster approaches school age and peer association.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Selection criteria

After approval from the Institutional Ethical Committee, health camps were organized with the help of the Community Medicine Department and health workers. A total of 241 consenting patients of ASA I and II aged 6 months to 20 years of either sex, scheduled for elective cheiloplasty and palatoplasty, were enrolled for the present study. Preoperative evaluation was done with main focus on upper airway anomalies, anemia, upper respiratory tract / chest infection, nutritional status and other associated congenital anomalies of cardiovascular system. None of them was apparently suffering from any other congenital syndromes associated with cleft abnormalities.

Blood biochemistry for hemoglobin, complete blood counts and bleeding disorder was done. X-rays chest and lateral view of neck were evaluated for chest disease and/ or difficult airway; and x-ray mandible, to exclude the Treacher Collins and Pierre Robin syndromes, when required. Instructions for preoperative fasting were given as per NPO (Nil Per Oral) guidelines, i.e., 2 hours for clear fluids, 4 hours for breast milk and 6 hours for formula feed and solid food.

General anesthesia for cheiloplasty and palatoplasty

Preoperatively, standard monitors for heart rate, blood pressure, temperature, ECG and SpO2 with EtCO2 probe were attached, and intravenous fluid (Isolyte-P / Ringer lactate) was started. A precordial stethoscope was used to monitor both heart sound and respiratory sounds, and warming blanket was used to avoid hypothermia. The patients were premedicated with glycopyrrolate (0.01 mg/kg) for antisialogogue and vagolytic effects. Sedative premedication was avoided due to risk of airway obstruction. After preoxygenation for 3 minutes, halothane induction was safely performed in the infants. Intravenous induction with thiopental, ketamine or propofol was preferred for older patients, in a dose sufficient to abolish the eyelash reflex. Laryngoscopy and intubation was facilitated with succinylecholine. Oral endotracheal intubation was performed with south-pole RAE (Ring-Adair-Elwyn) endotracheal tube of appropriate size. After confirming proper positioning of endotracheal tube, it was taped below the lower lip in the midline to minimize distortion of facial anatomy. The pharyngeal packing with moistened ribbon gauze was done to absorb blood and secretion. Bilateral air entry was reconfirmed after proper positioning of head extension for cleft surgery. Eyes were lubricated and protected with eye cover. After gag and pack insertion, ventilation was reassessed. Anesthesia was maintained with halothane and nitrous oxide 60% in oxygen with vecuronium 0.1 mg/kg. The patients were mechanically ventilated with adequate minute ventilation to maintain normocapnia. Parenteral fentanyl was used when required. In order to reduce blood loss and improve the surgical field, 2% xylocaine with adrenaline was used. Blood transfusion was not needed during cleft lip repair due to only modest amounts of blood loss, while repair of cleft palate was associated with moderate bleeding. Infraorbital nerve block was performed in selected cases of cleft lip and nasopalatine and palatine nerve block, for palatal surgery, by 0.25% bupivacaine for postoperative analgesia.

After completion of surgery, oral suction was done and pharyngeal pack removed. Residual neuromuscular blockade was reversed with neostigmine and glycopyrrolate, given in titrated doses. Tracheal extubation was undertaken after return of consciousness, good spontaneous respiration of adequate tidal volume and protective reflexes. Tongue suture was placed after palate surgery to allow forward retraction of tongue to prevent potential postoperative airway obstruction.

Postoperatively, the patients were nursed in lateral position to optimize air movement and to minimize the chance of aspiration. The monitoring for bleeding, vomiting or airway obstruction was done. The arm restrains, which prevent elbow flexion, were routinely used to keep the child's hands away from the face so as to prevent rubbing at the stitches and surgical site. Additional analgesia with diclofenac suppositories were used. No complication occurred during the postoperative period.

RESULTS

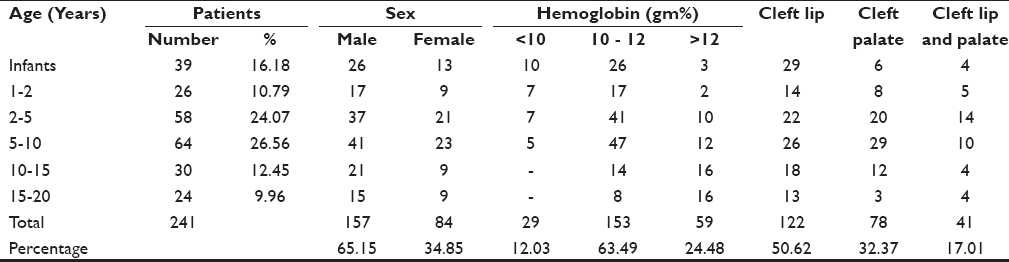

A total of 241 children, aged 6 months to 20 years, were studied under Smile Train. Only 27% of the children presented for surgery by the ideal age of 2 years. During infancy, only 39 (16.18%) patients were operated. There were 26 (10.79%) children of age 1-2 years; 122 (50.63%) children, 2-10 years; and 54 (22.41%) patients presented for surgery even at an age in the range of 10-20 years. They were of both sex 157 (64.154%) males and 84 (34.85%) females. Approximately two thirds of the patients were male [Table 1].

Table 1.

Age and sex distribution

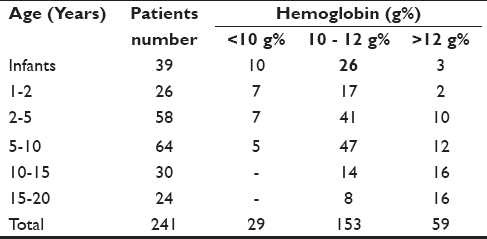

The hemoglobin was less than 10 g% in 29 (12.03%) patients of the younger age group and more than 12 g% in 59 (24.48%) patients of the older age group [Table 2]. Infants and children who were anemic with hemoglobin less than 10 g% were prescribed oral hematinics before the corrective surgery.

Table 2.

Hemoglobin

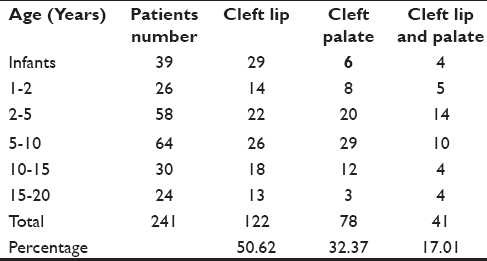

There were 122 (50.62%) patients of cleft lip, 78 (32.36%) patients of cleft palate and 41 (17.01%) patients of cleft lip and palate [Table 3].

Table 3.

Incidence of anomaly

Approximately 13.27% of children up to the age of 5 years were undernourished as per norms followed by IAP (Indian Academy of Paediatrics). These children were given dietary supplements as their weight was 80% or less than the standard. After improvement of their general health status, they were taken up for surgery.

In our study, more male patients had turned up for cleft lip and palate surgery; because in rural society, more attention is given to a male child.

DISCUSSION

Cleft lip and palate, considered together, constitute the third most common congenital anomaly that requires reconstructive surgical procedures at an early age. Infants with cleft lip and palate have problems with deglutition and upper respiratory tract infections. Anemia is often present, reflecting poor nutrition due to feeding problems.[1]

The functional goals of cleft lip and palate surgery are normal speech, hearing and maxillofacial growth. The cheiloplasty was done to fix the separation of the lip, and palatoplasty (Furlow procedure) was done to fix the roof of the mouth so that the child can eat and learn to talk normally. This corrective surgery can safely be performed under general anesthesia. Cleft lip alone in infants can be repaired within the first 6 months of life to ensure proper sucking, while cleft palate repairs are usually done between the ages of 9 and 18 months but before the age of 2 years, to ensure proper speech. It is thought that speech and hearing are improved by early cleft palate repair (before 24 months of age) and that the delayed closure (after 4 years of age) is associated with less retardation of mid-facial growth. An early two-stage palate repair is advocated, which involves closure of the soft palate at 3 to 6 months of age, with secondary closure of the residual hard palate at 15 to 18 months of age. It is vital for speech development and growth of soft palate.[2–4]

Preanesthetic assessment is valuable and includes history, physical examination and laboratory investigations for assessment of child, as repair will depend upon the health status of the child. The rule of 10 can be used: Weight- approximately 10 lb, hemoglobin- 10 g or more, white blood cell count- less than 10,000 per μL and age- around 10 weeks. Upper respiratory tract infection, anemia and under-nutrition were treated by giving antibiotics, dietary supplements and hematinics in consultation with a pediatrician; and food habits of the children were modified, which was necessary for better postoperative outcome. The clinical management was aimed at reducing the chance of aspiration and pulmonary compromise, for which these infants were fed in an upright position. The Haberman nipple was found to be the most successful for feeding the children.[5]

Anesthesia for cleft lip and palate surgery carries a high risk and morbidity related to the airway, either due to difficult intubation or postoperative airway obstruction.[6,7] Airway problems in children with cleft lip and palate have been recognized, and many methods of managing their difficult airway have been described; the use of firm pressure over the larynx to aid laryngoscopy with a bougie as a guide to tracheal intubation being one of them. More advanced methods involve fiber-optic techniques.[8] The laryngeal mask has been recommended as a guide to fiber-optic intubation in children[9] and has been used successfully in Pierre Robin,[10] Treacher Collin and Goldenhar syndromes. Specially designed light wands and laryngoscope are available for difficult intubation in children.[11] Retrograde techniques have been described in infancy with lower success rate in comparison to older children or adults.[12]

Assessment of the degree of difficulty of intubation is not always possible as some children may be uncooperative. Radiological assessment of pediatric airway can be done by measuring the maxillo-pharyngeal angle on lateral view of neck.[7] The degree of laryngoscopic difficulty decrease with increasing age. In infants with severe upper airway problems, there is also usually a history of significant feeding difficulties. Usually all difficult laryngoscopies have occurred in children with bilateral clefts or retrognathia. Provision of adequate postoperative analgesia is difficult because of the potential for respiratory depression which most analgesic drugs possess.

In this study, postoperative analgesia was provided by per rectum suppository of diclofenac and/ or low doses of opioids. Local anesthetic infiltration has provided useful intraoperative analgesia, but cleft palate was benefited by careful use of intraoperative opioids. Infraorbital nerve block was given to selected patients of cleft lip surgery and was found to be a very good and reliable technique to decrease analgesic requirements and offered an alternative method of pain relief after cleft surgery.[13,14]

A team approach is needed for management of, correcting, cleft anomaly, which is best provided in a multi-disciplinary setting with coordination among the members of the team so as to maintain communication between the specialist, patients and their families. Cleft management team must adopt a protocol that enables cooperation at all times throughout the growth phase of the child. These children need a pediatrician to maintain their overall health, a speech therapist to prevent or overcome the speech deficiencies and an orthodontist for early intervention to develop normal bite and dentition. The team also requires the participation of the cleft surgeon, health care workers, feeding advisor, clinical psychologist and counselor.

CONCLUSION

A total of 241 patients of cleft deformities, of both sex, were studied from infancy to adulthood. Only 27% of the patients came for surgery to the hospital at an ideal age. Majority (73%) of the patients reported for repair at an older age, that too probably due to persuasion and motivation by health workers, who stressed that under Smile Train, surgical treatment will be free and as a charity.

Efficient health care delivery during anesthesia and surgery with no morbidity and mortality, also motivated other patients to come forward for surgical correction.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gordon JR. A short history of anaesthesia for hare lip and palate repair. Br J Anaesth. 1972;43:796. doi: 10.1093/bja/43.8.796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hodges SC, Hodges AM. A protocol for safe anaesthesia for cleft lip and palate surgery in developing countries. Anaesthesia. 2000;55:436–41. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2000.01371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Law RC, Clark CD. Anaesthesia for cleft lip and palate surgery. Update in Anaesthesia. 2002;14:27–9. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doyle E, Hudson L. Anaesthesia for primary repair of cleft lip and cleft palate: A review of 244 procedures. Paediatr Anaesth. 1992;2:139–45. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen MM, Cameron CB. Should you cancel the operation when a child has an upper respiratory tract infection? Anesth Analg. 1991;72:282–8. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199103000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gunwardana RH. Difficult laryngoscopy in cleft lip and palate surgery. Bri J Anaesth. 1996;76:757–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/76.6.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hatch DJ. Airway management in cleft lip and palate surgery. Bri J Anaesth. 1996;76:755–6. doi: 10.1093/bja/76.6.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wrigley S, Black AE, Sidhu V. A fibreoptic laryngoscopy for paediatric anaesethesia. Anaesthesia. 1995;50:709–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1995.tb06100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dubreuil M, Ecoffey C. Laryngeal mask guided tracheal intubation in paediatric anaesthesia. Paediatr Anaesth. 1992;2:344. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baraka A. Laryngeal mask airway for resuscitation of a newborn with Pierre- Robin syndrome. Anaesthesiology. 1995;83:645–6. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199509000-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hasan MA, Black AE. A new technique for fibreoptic intubation in children. Anaesthesia. 1994;49:1031–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1994.tb04349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooper CM, Murray-Wilson A. Retrograde intubation: management of a 4.8 kg, 5 month infant. Anaesthesia. 1987;42:1197–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1987.tb05228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bosenberg AT, Kimble FW. Infraorbital nerve block in neonates for cleft lip repair; anatomical study and clinical application. Br J Anaesth. 1995;74:506–8. doi: 10.1093/bja/74.5.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahuja S, Datta A, Krishna A, Bhattacharya A. Infra-orbital nerve block for relief of postoperative pain following cleft lip surgery in infants. Anaesth. 1994;49:441–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1994.tb03484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]