Abstract

Objective:

To compare spinal anesthesia with the gold standard general anesthesia for elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy in healthy patients.

Materials and Methods:

Controlled, prospective, randomized trial of 60 patients with symptomatic gallstone disease and American Society of Anesthesiologists status I or II were operated for laparoscopic cholecystectomy under spinal (n=30) or general (n=30) anesthesia between the academic years March 2009 and July 2010.

Results:

All the procedures were completed by the allocated method of anesthesia, as there were no conversions from spinal to general anesthesia. Pain was significantly less at 4 hours (P<0.0001), 8 hours (P<0.0001), 12 hours (P<0.0001), and 24 hours (P=0.0001) after the procedure for the spinal anesthesia group, compared with those who received general anesthesia. There was no difference between the two groups regarding complications, hospital stay, recovery, or degree of satisfaction at follow-up.

Conclusions:

Spinal anesthesia is adequate and safe for laparoscopic cholecystectomy in otherwise healthy patients and offers better postoperative pain control than general anesthesia without limiting the recovery.

Keywords: General anesthesia, laparoscopic cholecystectomy, spinal anesthesia

INTRODUCTION

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy has become very popular after it was first described in 1987 by Phillipe Mouret in France. Laparoscopic surgical techniques have been rapidly accepted by surgeons worldwide with published reports describing the benefit of less postoperative pain, decreased hospital stay and earlier return to work.[1] Minimally invasive therapy is done with the general aim to minimize the trauma of interventional process whilst still achieving satisfactory result.[2]

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy under regional anesthesia alone has been reported only occasionally in the past; these reports included patients unfit to receive general anesthesia, mainly patients with severe chronic obstructive airway disease.[3,4] Hamad and Ibrahim El-Khattary[5] used spinal anesthesia for laparoscopic cholecystectomy for the first time in a small series of healthy patients but they had used nitrous oxide as a pneumoperitoneum instead of standard carbon dioxide. Recently, it has been shown that laparoscopic cholecystectomy can be done successfully using carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum under spinal anesthesia in healthy patients with symptomatic gallstone disease.[6]

Also, the incidence of postoperative morbidity like nausea, vomiting, dizziness, respiratory complication, thromboembolism and pneumonia was much less as compared to general anesthesia.[7] Also, the total cost of spinal anesthesia with respect to hospital stay, induction and recovery, the need for postoperative antiemetics and analgesia and the incidence of other complication was much lower when compared to general anesthesia.[8]

In our study, we compared spinal anesthesia with general anesthesia, the gold standard uptil now, in laparoscopic cholecystectomy in healthy American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade 1 and 2 patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A study was carried out in 60 patients of either sex, undergoing elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy using spinal anesthesia and general anesthesia between the academic years March 2009 and July 2010, after taking informed consent under medical ethics. Patients of age between 18 and 60 years with ASA physical status I and II were included in the study. The patients with ASA grade III and IV high risk patients, all emergency procedures, bleeding disorders, acute cholecystitis, pancreatitis and acute cholangitis, previous open surgery in upper abdomen, contraindication for pneumoperitoneum, cardiovascular disorders, respiratory disorders, renal disease and liver disease, circulatory instability, and patients with known sensitivity to local anesthetics were excluded from the study.

All the patients were examined to assess their preoperative condition, demographic data and routine investigations which were recorded in brief. The patients were divided into two groups of 30 each: group A receiving general anesthesia and group B receiving spinal anesthesia.

After taking the patients to the operation theater, an intravenous line was secured in the right upper limb and infusion of 500 ml of Ringer's Lactate solution started. Blood pressure cuff, ECG electrode and capnography monitor were applied. The initial pulse, blood pressure (BP), respiratory rate, ECG and end tidal CO2 (EtCO2) were noted. All the patients were premeditated with Inj. Glycopyrrolate 4 mcg/kg, Inj. Midazolam 0.02 mg/kg and Inj. Ondensetron 0.08 mg/kg intravenously (i.v.).

In patients randomized for spinal anesthesia, the patient was first made to lie in supine position and all the monitors were attached. Oxygen was then administered through ventimask at 3 l/minute. Then the patient was made to lie in left lateral decubitus position. A 25-G Quincke spinal needle was introduced in subarachnoid space at L3–L4 interspace under all aseptic and antiseptic precautions. After confirming free flow of cerebrospinal fluid, 0.3 mg/kg of hyperbaric Bupivacaine 0.5% was injected intrathecally in cephalad direction at a velocity of 0.1 ml/second. Then, after keeping the patient in the 15° Trendelenberg position for 5 minutes, the patient was again made to lie in a supine position. Approximately 10 minutes after intrathecal injection, the level of analgesia was checked. During this period, 500 ml of 0.9% Ringer's Lactate was infused. A segmental sensory (pin-prick) block, extending between T4 and L5 dermatomes, was obtained without any respiratory distress.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed using the same techniques in both the groups with standard 4 trocar insertion. After painting and draping, Inj. Bupivacaine plain (0.2%) 20 ml was injected subcostally under diaphragm equally on both sides in both the groups.[9,10] Pneumoperitoneum was established by using the open (Hassen) technique with carbon dioxide at maximum intra-abdominal pressure of 12 mm Hg. Intraoperatively, the patients randomly allocated to general anesthesia group received fentanyl citrate 2 μg/kg i.v. as an adjuvant while those allocated to spinal anesthesia group were given 25 μg i.v. as bolus and when required. All the patients were monitored continuously both for clinical observation and noninvasive hemodynamic monitoring like electrocardiography, pulse, blood pressure, respiratory rate, pulse oxymetry and EtCO2 which were recorded at 15 minute interval. Operative times as well as any intraoperative events such as shoulder pain, headache, nausea, and discomfort were recorded.

Postoperative pain was assessed at 4, 8, 12 and 24 hours by using the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) after completion of procedure. Other postoperative events, either related to surgical or especially to anesthetic procedure, such as discomfort, nausea and vomiting, shoulder pain, urinary retention, pruritus, headache and other neurological sequel, were recorded.

RESULTS

None of the patients withdrew their consent and there was no conversion to open cholecystectomy.

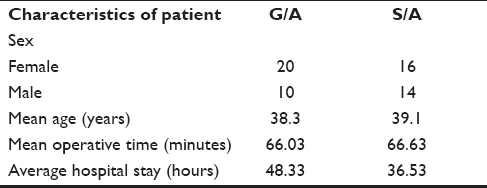

Demographic data are shown in Table 1 and were similar in both the groups.

Table 1.

Demographic data

All the procedures were completed within the allocated method of anesthesia and there was no conversion of spinal to general anesthesia. Intraoperatively, there was no bradycardia in either group. In group B, hypotension (i.e. >30% fall in BP) was noted in 9 (30%) cases, out of which mephentermine 6 mg was given in only 2 cases and the rest were managed with i.v. fluids, while in group A, hypotension was noted in 3 (10%) cases and all of them were managed with i.v. fluids. Pain/discomfort in right shoulder was noted in 7 (23%) cases but it was severe enough in only 3 (10%) cases which received i.v. fentanyl 25 μg bolus once. Rest were managed with massage over right shoulder. The remaining patients did not require any additional medication or other intervention, and procedures were completed uneventfully in all cases.

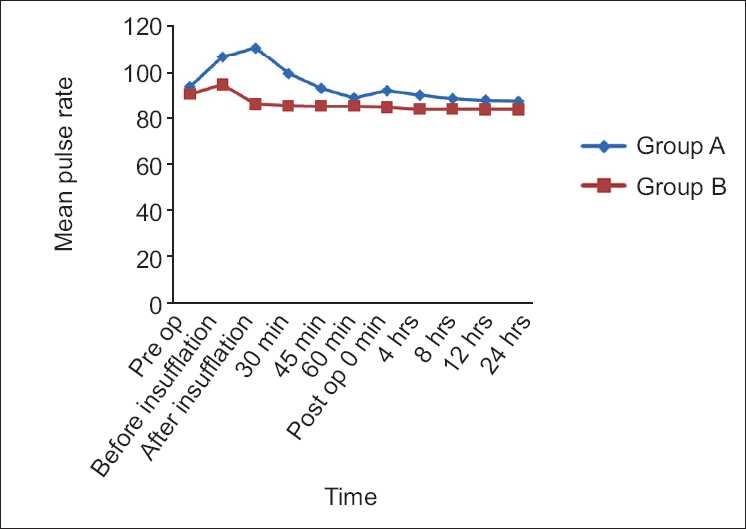

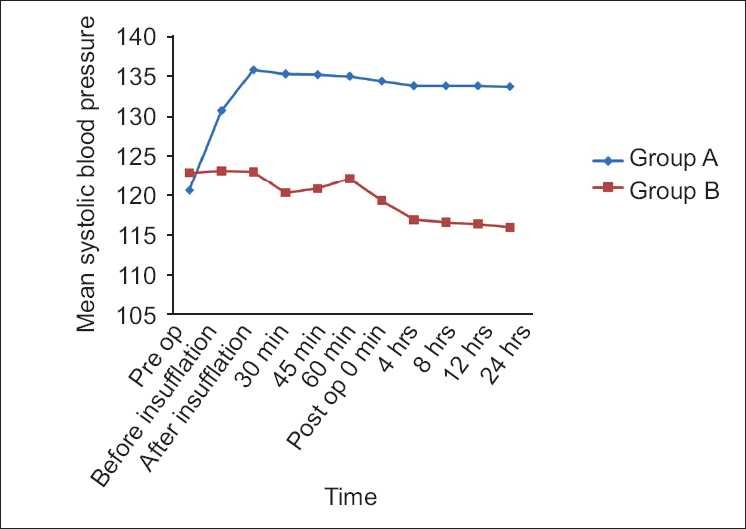

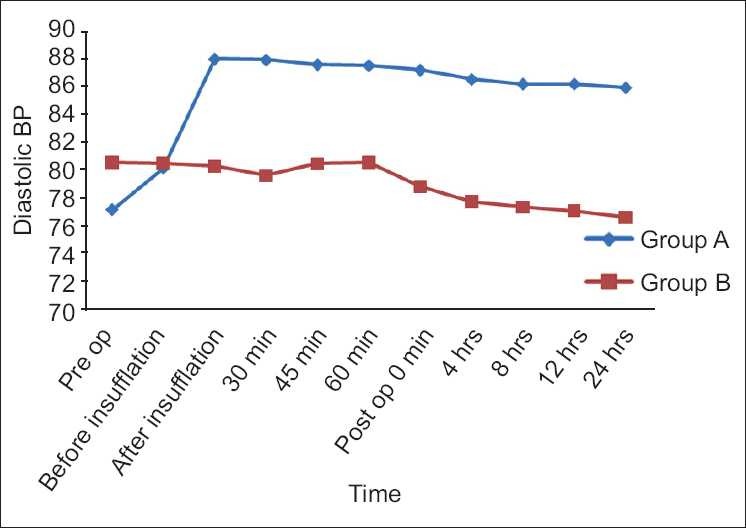

Figure 1 shows intraoperative comparison of mean pulse rate in group A and group B shows less tachycardia. Figures 2 and 3 show mean systolic and diastolic pressure, respectively, in both the groups, which was found to be higher in group A compared to group B.

Figure 1.

Perioperative comparison of mean pulse rate in groups A and B

Figure 2.

Perioperative comparison of mean systolic blood pressure in groups A and B

Figure 3.

Perioperative comparison of mean diastolic blood pressure in groups A and B

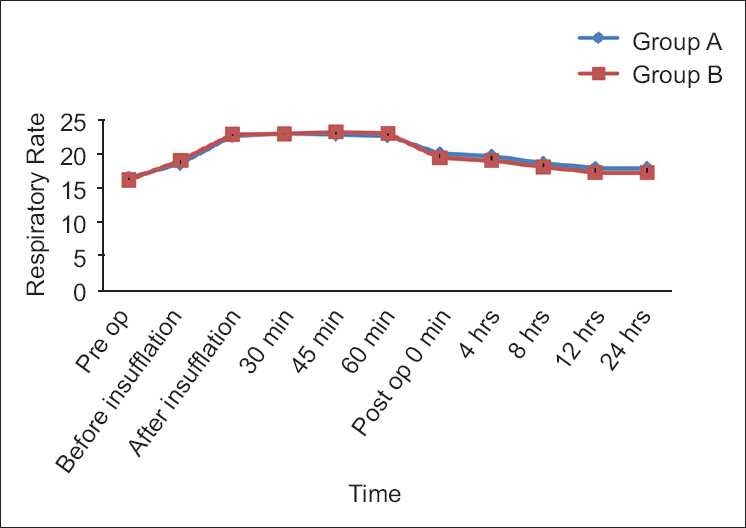

In group A, to maintain the EtCO2 in between 35 and 40 mm Hg, respiratory rate has to be increased, while in group B, in spontaneously ventilated patients of spinal anesthesia, the increase in respiratory rate was similar to that of group A. This shows that there was no pain or respiratory distress in group B as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Perioperative comparison of respiratory rate in groups A and B

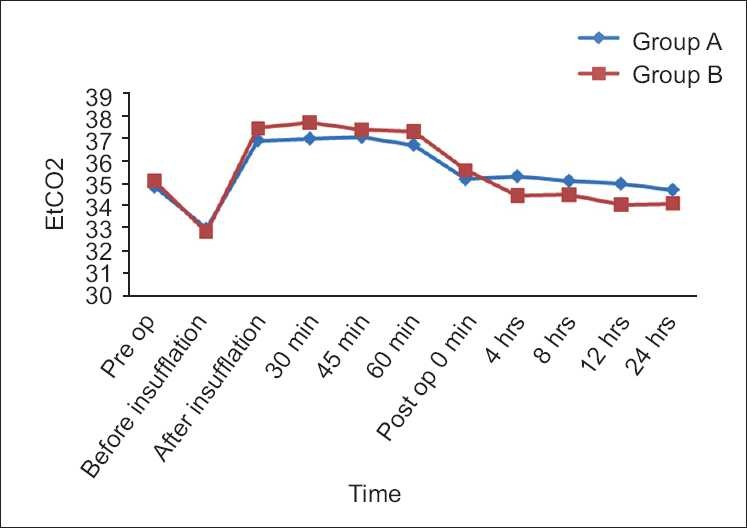

Figure 5 shows that the mean EtCO2 in both the groups initially increased after peritoneal insufflations and then gradually returned to baseline values after several minutes. Hence, EtCO2 readings in both the groups were similar.

Figure 5.

Perioperative comparison of EtCO2 in groups A and B

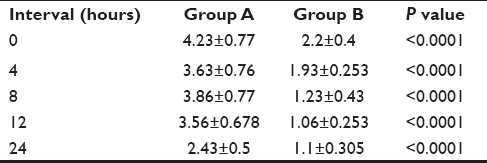

Mean discharge from the hospital in group A was 48.33 hours and in group B it was 36.53 hours. There was no mortality or morbidity in either group. Regarding the postoperative complications, nausea was present in 10 (30%) cases in group A while none had it in group B. Dizziness was there in 6 (20%) cases in group A while none had it in group B. Pruritus was there in 4 (13%) cases in group A and 2 (6.6%) cases in group B. There was no shoulder pain in cases of either group. VAS score was highly significant postoperatively at 0, 4, 8, 12 and 24 hours while comparing both the groups, which suggests that group B had better analgesia than that of group A [Table 2].

Table 2.

Visual analogue scale score

Pain at local site was noted in 20 (66%) cases in group A and in only 4 (13%) cases in group B. VAS score of >5 received rescue analgesia in the form of i.v. fentanyl 25 μg. There was no headache, backache, urinary retention or any other major complication. At the time of discharge, all patients were asked about the satisfaction regarding the general as well as spinal anesthesia and the patients were more satisfied with spinal anesthesia than general anesthesia.

DISCUSSION

The present study has not only confirmed the feasibility of safely performing laparoscopic cholecystectomy under spinal anesthesia as the sole anesthetic procedure but also shown superiority of spinal anesthesia in terms of better postoperative pain control as compared to general anesthesia. Pain assessed throughout any time in the postoperative period during the patients’ hospital stay was significantly lesser in spinal group as compared to general anaesthesia group, which is due to residual analgesic effect of local anesthetic in subarachnoid space and decrease in discomfort due to avoidance of general anesthesia.[6,11] Pain relief, an important component for rapid and smooth recovery, was seen in spinal anesthesia group.

Intraoperatively, two things were noted – hypotension and pain/discomfort in right shoulder in the spinal group. Hypotension is due to sympathetic blockade and mechanical effect of pneumoperitoneum, while pain and discomfort over right shoulder can be attributed to diaphragmatic irritation from pneumoperitoneum with carbon dioxide. Most of this was managed without drugs, i.e., reassurance to the patient, massage of the right shoulder, keeping the intra-abdominal pressure to 12 mm Hg, avoiding excessive tilting of table and thereby minimizing diaphragmatic irritation. In our study, diaphragmatic irritation was much less as there was subcostal instillation of Inj. Bupivacaine plain (0.2%) 10 ml each on both sides just prior to incision. Sometimes, this diaphragmatic irritation is so severe that there may be conversion of the procedure to general anesthesia. The use of low pressure pneumoperitoneum was adequate, especially with spinal group, as spinal anesthesia causes high level of motor, sensory and sympathetic blockade and thereby good abdominal muscle relaxation as compared to general anesthesia.

In group A, the initial increase in pulse rate and BP after peritoneal insufflations are due to both mechanical and neurohumoral effects.[12] The return of pulse rate and BP to normal baseline was gradual. In group B, there was little variation in pulse and BP after peritoneal insufflation as spinal anesthesia tends to decrease the pulse and BP, while the neurohumoral and mechanical effects of pneumoperitoneum tend to increase them. After several minutes, the neurohumoral and mechanical effects are compensated so that there is slight decrease in the pulse rate and BP. The decrease in pulse rate and BP in group B as compared to group A can be explained as due to decrease in pain caused by residual analgesic effect of local anesthetic in subarachnoid space.

Nausea and vomiting are particularly troublesome after laparoscopic surgery; over 50% of patients required antiemetics, so prophylactic antiemetics had been given routinely. Regarding the postoperative complications, nausea, vomiting and dizziness were more common with general anesthesia due to intubation of trachea and intravenous drugs.

As spinal anesthesia is a regional block, there is less procedure-related cost and hospital stay because of less postoperative pain and complications.

CONCLUSION

In this controlled, randomized, prospective study, in which a comparison of spinal anesthesia versus general anesthesia in otherwise healthy laparoscopic patients was done, we observed that spinal anesthesia was better than general anesthesia in terms of postoperative pain relief. Secondly, spinal anesthesia was better in terms of hospital stay, cost, nausea and vomiting and procedure-related satisfaction.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Soper NJ, Barteau JA, Clayman RV, Ashley SW, Dunnegan DL. Comparison of early postoperative results for laparoscopic versus standard open cholecystectomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1992;174:114–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wickham JE. Minimal invasive surgery: Future developments. Br Med J. 1994;308:193–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6922.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gramatica L, Jr, Brasesco OE, Mercado Luna A, Martinessi V, Panebianco G, Labaque F, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy performed under regional anesthesia in patients with obstructive pulmonary disease. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:472–5. doi: 10.1007/s00464-001-8148-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pursnani KG, Bazza Y, Calleja M, Mughal MM. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy under epidural anesthesia in patients with chronic respiratory disease. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:1082–4. doi: 10.1007/s004649900785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamad MA, El-Khattary OA. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy under spinal anesthesia with nitrous oxide pneumo-peritoneum: A feasibility study. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1426–8. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-8620-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tzovaras G, Fafoulakis F, Pratsas K, Georgopoulou S, Stamatiou G, Hatzitheofilou C. Spinal vs general anesthesia for laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Interim analysis of a controlled randomized trial. Arch Surg. 2008;143:497–501. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.5.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodgers A, Walker N, Schug S, McKee A, Kehlet H, van Zundert A, et al. Reduction of postoperative mortality and morbidity with epidural or spinal anesthesia: Results from overview of randomised trials. BMJ. 2000;321:1493. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7275.1493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chilvers CR, Goodwin A, Vaghadia H, Mitchell GW. Selective spinal anesthesia for outpatient laparoscopy.V: Pharmacoeconomic comparison vs general anesthesia. Can J Anesth. 2001;48:279–83. doi: 10.1007/BF03019759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alkhamesi NA, Peck DH, Lomax D, Darzi AW. Intraperitoneal aerosolization of bupivacaine reduces postoperative pain in laparoscopic surgery: A randomized prospective controlled double-blinded clinical trial. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:602–6. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-9087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupta A. Local anaesthesia for pain relief after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A systematic review. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2005;19:275–92. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aono H, Takeda A, Tarver S, Goto H. Stress responses in three different anesthetic techniques for carbon dioxide laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Clin Anesth. 1998;10:546–50. doi: 10.1016/s0952-8180(98)00079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wahba RW, Beique F, Kleiman SJ. Cardiopulmonary function and laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Can J Anaesth. 1995;42:51–63. doi: 10.1007/BF03010572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]