Abstract

Objectives:

To set up and validate a patient satisfaction questionnaire based on Iowa Satisfaction in Anesthesia Scale (ISAS) for evaluating the degree of patient satisfaction in anesthesia.

Materials and Methods:

We established and validated a survey questionnaire of 13 questions measuring the following dimensions adequacy of patient information; participation in decision making, nurse patient relation, accessibility of communication with the anesthesiologist, patient fear and anxiety and the post anesthesia care management. The process passed through three steps: instrument validation, survey conduction and data analysis. Cronbach's alpha was used to measure the reliability and standard psychometric techniques were used to measure instrument validity.

Results:

Our modified instrument shows good reliability which is obvious with a Cronbach's alpha value of 0.72 and all the perspectives of validity (face, content and construct). Also, 173 (21.54%) patients achieved an overall satisfaction score of less than 85% female patients are were less satisfied than male patients. Educated patients were less satisfied, and those belonging to ASA group I and II were significantly less satisfied. Dimensions pinpointed are related to information and decision making, adverse events in recovery room, fear and anxiety contributed to patient dissatisfaction.

Conclusion:

The instrument used for the evaluation of patient satisfaction in anesthesia is a valid tool for the Arabic speaking patients. There is room for improvement in the anesthesia care, mainly in the dimension of information, decision making and postoperative anesthesia care.

Keywords: Anesthesia, Iowa satisfaction in Anesthesia Scale, patient satisfaction, questionnaire

INTRODUCTION

Patient satisfaction, defined as the degree of fulfilling patient anticipation, is an important component and quality indicator in healthcare[1]. Measuring patient satisfaction is nowadays a necessity[2]. The American Productivity Quality Center reports that satisfied customers tell another 5 people about their positive experiences, whereas those who received poor services tell another 9 to 20 people.[3] The measurement of satisfaction in anesthesia practice is quite difficult as subjective indicators depend on different civilizations, cultures, and backgrounds[4]. The most popular instrument used for this purpose is the Iowa Satisfaction in Anesthesia Scale (ISAS) an instrument intended to measure the satisfaction in Monitored Anesthesia Care (MAC).[5]

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was performed after getting approval from the ethical committee in two hospitals in Saudi Arabia (Makkah and Riyadh) with different patient characteristics.

Instrument design

Initially the idea was to implement the ISAS[5] to our patients. A written approval from Dr. Dexter (original inventor of ISAS) was obtained. Then, the ISAS was translated to Arabic language and submitted to a focus group of anesthesiologists who reached a consensus that these questions in such a form were not appropriate for the culture of our patients; the negative and positive agreement and disagreement as per ISAS were not appropriate for the Arabic speaking patient. This modification required revalidation of the instrument. At this stage we included in the content of our questions the preoperative anesthesia phase and the postoperative anesthesia care.

Initial questionnaire

We followed the guidelines of questionnaire design in being simple, short and reflecting a defined measured dimension[6]. We designed a set of 20 questions eight questions covering the preoperative period, four questions evaluating the operating room holding area and five questions measuring the satisfaction in the recovery room and two questions covering the post anesthesia visit. The last question assessed the readiness of the patient to undergo or recommend the same service to his family members and friends; this question had to be used for correlation with the overall satisfaction. We intended to formulate question number 19 negatively as a test of patient comprehensibility of the survey. At the end of the questions, the patient was a given a free space to add his/her comments.

Scoring process

We used the 5-point psychometric Likert scale[7] to evaluate the degree of patient agreement to a given statement, as follows score 5 for Strongly Agree, 4 for Agree, 3 for Undecided, 2 for Disagree and 1 for Strongly Disagree. Question number 19 was given a reversed score because of its negative formulation.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients with American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification I, II, III, aged 18 and above, performing elective surgery under general or regional anesthesia and staying in the hospital for more than 24 hours were included. All patients were Arabic speakers with education level above the 6th grade. We excluded patients under the age of 18 years, non-Arabic speakers, patients undergoing emergency surgeries or surgeries that require planned or unplanned postoperative intensive care admission.

Pilot study

In March 2009, our initial questionnaire was distributed to a pilot group of 80 patients.

Questionnaire distribution and collection

Questionnaire was submitted to the patient immediately upon discharge from recovery room with a cover letter that included a brief explanation about the process. Collection of the questionnaire was performed by the surgical ward nursing staff.

Testing convergent validity

Convergent validity test indicates the degree of agreement between measurements of the same trait, obtained by different approaches. We used for this purpose one of Dexter's methods for validation in which the patients mean satisfaction score is compared with the score of the readiness of the patient to recommend the same service, as a proxy for positive word in the mouth. If the survey is a valid measure of patient satisfaction, it should relate theoretically to important criteria known to be associated with satisfaction, such as patients’ intention to recommend the hospital to others.

Testing validity

Validity was tested as regards face validity which inspected whether our questionnaire looks like is going to measure the satisfaction during anaesthesia care, and also content validity to check whether all the intended dimensions of the construct were covered, based on the free comments given by the patients at the end of the questions.

Testing reliability

We used the most popular reliability test, Cronbach's alpha[8] to measure the internal consistency of our survey on the 80 patients value >0.70 suggests adequate internal consistency). A “test retest” for the same sample was as well conducted in a 15-day interval as an additional tool for testing reliability.

Final questionnaire

After analyzing the results of the pilot study, the final questionnaire was prepared study was conducted in the two hospitals between April and November 2009. One thousand questionnaires were distributed, considering the same inclusion criteria.

Creation of dimensions

The dimensions of care that our survey was projected to measure were the adequacy of preoperative patient information and involvement in decision making, easy accessibility of contacting the anesthesiologist, degree of respect from nursing staff in operating room, adequacy of management in the post anesthesia care and the degree of handling patient fear and anxiety.

We studied the overall satisfaction and the dimensional satisfaction to detect the problematic areas. We compared between genders, ASA and education levels and studied their relation to the degree of satisfaction.

Data analysis

Data from both centers were processed and analyzed using Microsoft Excel.

RESULTS

Pilot study

Cronbach's alpha was 0.72 suggesting adequate internal consistency, giving our questionnaire a satisfactory reliability. Our questions appear to measure the construct; this was assessed through a focus group of professional people working in anesthesia.

Patients’ comments at the end of the questionnaire have little effects on the design of the questions, which supports the content validity of our instrument.

Final questionnaire

Based on the pilot analysis, only few modifications were made and were related to the number of questions. We removed the two questions related to the post anesthesia visit as it is not a standard of practice in several anesthesia departments. Some questions related to some minor complications in recovery room showed extremely skewed distribution in contributing to the dissatisfaction; therefore, we integrated them as one question. No changes were made regarding the scoring process. The final questionnaire consisted of 13 questions, in which question 12 was now the negatively formulated one and question 13 was the one used for correlation with the overall satisfaction (the mean score of the first 12 questions). There was a strong positive correlation shown by a Pearson coefficient of 0.84.

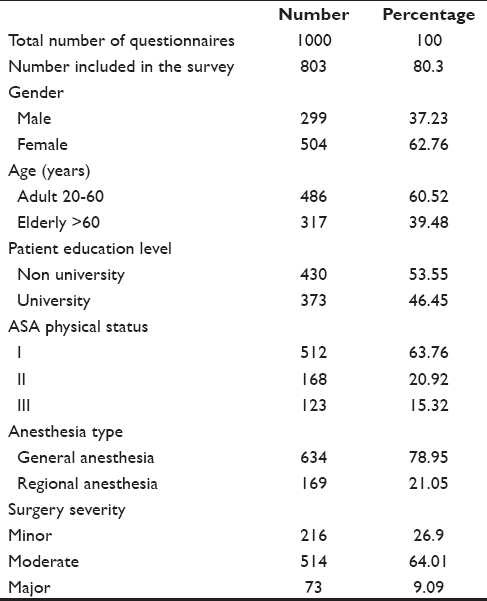

Demographic analysis

One thousand patients participated in the study, 197 responses were excluded due to incompleteness or the patient did not submit the questionnaire back. The remaining 803 valid responses were demographically analyzed as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic data

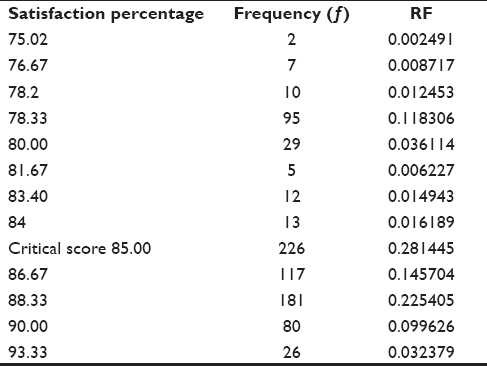

Satisfaction analysis

Our study showed that the percentage of overall patient satisfaction ranged between 75.02% and 93.33% [Table 2].

Table 2.

Frequencies and relative frequencies (RFs) of satisfaction percentages

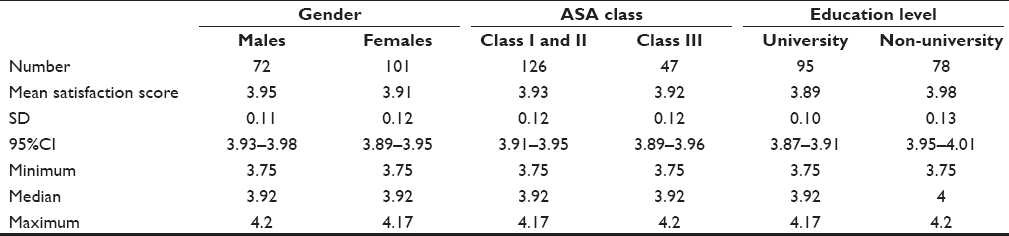

Hypothetically, we considered 85% as the critical satisfaction percentage below which a patient was classified as dissatisfied. Accordingly, 173 patients with a score of less than 85%, representing 21.54% were dissatisfied. Demographically, the dissatisfied patients were distributed as follows: 101 female patients representing 58.38%; 126 patients belonging to ASA groups I and II (72.83%); 95 patients with university level of education (54.91%). Females, ASA I and II patients, and those with university level of education were significantly more dissatisfied than their counterparts P 0.001 [Table 3].

Table 3.

Statistical analysis of the unsatisfied patients based on gender, ASA class and educational level

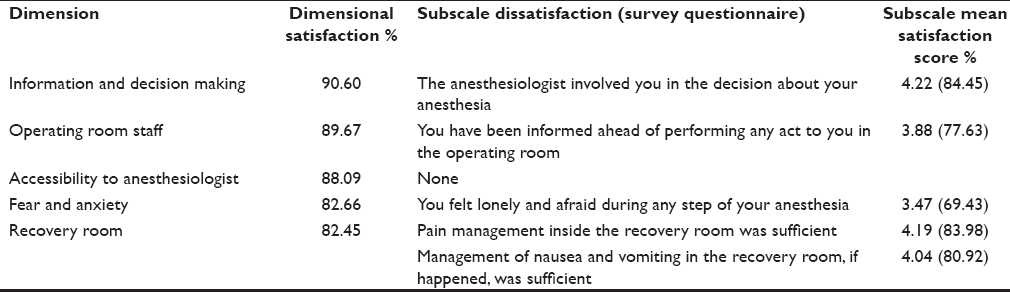

Dimensional analysis

To identify the areas of dissatisfaction, we analyzed the mean satisfaction score in each dimension and its subscales. Although the mean satisfaction score in the 1st dimension was 4.53 (90.6%), one of its subscales had a mean score of 4.22 (84.4%) mirroring that our patients were not satisfied about their participation in decision making. The mean satisfaction score in the 2nd dimension was 4.48 (89.67%) one of the subscales, patient/ nursing relation, was below 85%. The 3rd dimension score was 4.40 (88.09). The 4th and 5th dimensions, the management in the recovery area and patient fear and anxiety, with their integrated subscales, all had mean satisfaction scores below 4.25 (85%); an area with an obvious need to be improved [Table 4].

Table 4.

Dimensional patient satisfaction

DISCUSSION

The improvement in anesthesia safety contributes considerably to the advancement in surgical outcomes.[9] Patient satisfaction is considered as an important healthcare outcome measure[10] Patients’ rating can reflect many aspects of care not easily examined in any other manner;[11] so, the results obtained from any satisfaction survey must be critically examined. A credibility instrument to measure patient satisfaction must be valid and reliable. literature survey revealed several patient satisfaction questionnaires exploring the patient feedback on anesthesia care, and none of them targeted the Arabic speaker patient. A report by Dexter et al.[5] using the ISAS seems to offer one of the best psychometric approaches for collection of patient satisfaction data and contains all of the psychometric properties necessary for useful measurement based on the established criteria.[12] After we translated ISAS to Arabic, the instrument was not found to be appropriate for the culture of our Arabic patients. Thus, we were obliged to modify it accordingly. This modification necessitated a revalidation process. We used the same tools and approaches used by Dexter in our revalidation process. Our modification complied with two important elements: comprehensibility by our Arabic speaker patient and expanding the questionnaire to include the preoperative and postoperative anesthesia care since Dexter's questionnaire is limited to MAC only. We used ISAS as a starting point of our questionnaire and modified it according to our needs since it is accepted in the literature to adopt and adapt. Caljouw et al.[13] based their questionnaire on l'échelle de vecu préopératoire de l'anesthesie (EVAN) Questionnaire of Auquier and colleagues as a starting point to develop a new questionnaire during their development of Leiden Perioperative care Patient Satisfaction questionnaire (LPPSq).[14] Our instrument shows that it is reliable and valid to be implemented for Arabic speaking patients. The pilot questionnaire distributed to 80 patients showed accepted reliability and valid psychometric parameters.

We distributed 1000 questionnaires, out of which only 803 valid return questionnaires could be evaluated, representing 80.3%. Some questionnaire based studies are conducted in a semi-structured method in which the interviewer completes the questionnaire to achieve a higher valid return rate.[10] We did not follow that method although we were keen to remind our patients through the surgical nursing staff to complete the survey. In order to analyze the causes of patient dissatisfaction, we hypothetically considered an average score below 85% (mean 4.25) as dissatisfaction. We were confident that reaching the level of 85% satisfaction is fair enough as a baseline, as this will give us room for a future resurvey to target another elevated average. Some studies reached a percentage of satisfaction of 97%, but even with those results of only 3% dissatisfaction, the authors questioned those results and stated that there was an element of underreporting of the dissatisfaction.[15] Other studies explain the high rate of patient satisfaction as the unwillingness from the patient to criticize their care giver; however, halo effect and acquiescence bias are important to be considered in interpreting results from such studies.[1] Our degree of overall patient satisfaction is very similar to that of several other studies.[16–18] Our data were collected from two centers with different scope of services and patient characteristics to enable us to screen a wider range of patients and help us discover our patient needs. The patient satisfaction questionnaire was submitted to the patient immediately after discharge from recovery room and collected the day after because the patients usually do not differentiate between the outcome of anesthesia as a separated service from surgery. If we had conducted the survey after patients’ discharge from the hospital, their reply to anesthesia satisfaction could have been influenced by the overall outcome such as surgery and hospital stay. Our final questionnaire contained 13 questions covering specific elements that each patient goes through once while undergoing any surgical procedure. The questionnaire included structured items that relate directly or indirectly to the patient care at various stipulated levels of anesthesia care. The questionnaire was designed to be brief enough, practical and user-friendly but thorough enough to cover key clinical and environmental factors that are important to the patient and we are convinced that using simplified comprehensive questions targeting specific steps during the patient journey is more informative for future improvement than using a set of 30 or 40 questions. Each set of our questions was intended to measure a specific dimension of care. Our results confirm the deficit as regards patient information and involvement in anesthesia decision (satisfaction of 84.45%) although a high satisfaction rate was obtained for the comprehensibility of our anesthesia information flyer (94.62%). This was supported by O’Cathain et al.[19] who showed that the use of evidence based leaflets was not effective in promoting informed choice. This can only be interpreted that the patient is willing to have more information delivered to him directly from the anesthesiologist in the preoperative assessment, with a desire to build interpersonal relation with the anesthesia provider and discuss anesthesia options. The defect in this dimension is not specific to our finding but it is as well reported in the result of Heidegger et al.[20] The second dimension that our survey was predicted to judge was the accessibility to the anesthesiologist. We found that most of the patients were satisfied in this regard. The interpersonal relation between the patient and nursing staff in the operating room is a very important aspect of care; treating the patient with respect and courtesy, informing the patient honestly about the real cause of delay if it had happened in the operating room holding bay made the patient feel comfortable. The patient does not mind the delay unless concretely informed about what is going on. Information in this regard is mandatory to achieve satisfaction.[21] The immediate postoperative management of the patient in the recovery room is a vital element of anesthesia care and affects significantly the overall patient satisfaction rating, especially pain management and the undesirable nausea and vomiting. Postoperative pain should be aggressively managed in the recovery phase. The ongoing debate of the relative benefits of prophylactic vs. rescue antiemetic therapy should take each patient preference.[22] Results from several studies show that there is higher patient satisfaction if the pain postoperatively is well controlled,[23–28] there is no postoperative nausea and vomiting, with good pre- and post-operative information delivered.[26,27] We found ourselves confronted with a major defect in the recovery room satisfaction dimension (77.17%) as well as its subscale. Here, we had to correlate if this dissatisfaction was related to the type of surgery associated with increased nausea and vomiting incidences, such as abdominal surgery. Even if this is the real cause of this defect, more must be done in this direction to improve the outcomes. We did not analyze if the patients who received general anesthesia were less or more satisfied than the patients receiving loco regional anesthesia, as it is out of the scope of our study. Patient fear and anxiety throughout the anesthesia was very obvious (57.4%). Fear can be managed pharmacologically by adequate premedication and anxiolytic agents, but primary it should be done by increasing the trust between patient and anesthesia staff, and therefore, this dimension correlates significantly with the dimension of patient information. Analyzing our results as regards gender, education level and anesthesia severity score classification ASA, we found that female dissatisfaction was significantly higher than male dissatisfaction. Also, patients with ASA I–II were significantly less satisfied than ASA III patients, and university-level educated patients were less satisfied than others. Our explanation for this is related to the fact that female patients are more prone to postoperative nausea and vomiting and have a lower threshold for pain. Our results correlate with those of the studies which reported that women expressed more fears and different concerns about anesthesia than men.[23] In other studies, it was found that there were no significant differences in scores among the other patients. Regarding sex differences, educated patients have a higher expectation rate than others and if we do not meet these expectations, the patient satisfaction is not fulfilled. The anesthesiologist behavior once facing surgery with ASA III shows more concern and dealing with the patient accordingly. A good positive correlation was found between the patients’ overall mean satisfaction results and the result of the patient's intention to go through or recommend the service to his family and friends (Pearson coefficient of 0.85). We cannot confirm that it was appropriate to formulate a question negatively where the scoring was given in reverse order; the mean satisfaction for this question was 57.23%. At the same time, we did not remove this question from our survey and it can be considered as a limitation for our study. But further research must be carried out as regards the Arabic patient comprehensively of a negatively formulated question, especially by less educated patient.

CONCLUSION

Our study demonstrates that the three essential variables of high satisfaction with anesthesia are adequate preoperative patients’ information, effective management of patient anxiety, and efficient postoperative care.

Postoperative pain management must be tailored according to patients’ needs and must be included in the anesthesia plan as well as nausea and vomiting prevention to achieve maximum results. More effort must be taken to achieve satisfaction by female patients as this section of people requires more effort to be satisfied. In this growing era of quality assurance and cost containment, and assuring patient safety, clinicians should take patients’ preferences into consideration when developing guidelines and planning anesthesia care.

This was the first multicenter study exploring patient satisfaction on anesthesia in Saudi Arabia and targeting Arabic speaking patients. It was conducted on a voluntary basis by a group of anesthesiologists moved by a consistent spirit, to accomplish a shared goal.

Acknowledgments

Mortality and Morbidity Anesthesia Forum moderated by Prof. Abdelazim Dawlatly, King Saud University, Riyadh, KSA.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hall JA, Dornan ME. What patients like about their medical care and how often they are asked. A meta-analysis of the satisfaction literature. Soc Sci Med. 1988;27:935–9. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(88)90284-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bolus R, Pitts J. Patient Satisfaction: The Indispensable Outcome. Manag Care. 1999;8:24–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Productivity Quality Center. How to avoid the traps of benchmarking customer satisfaction. Continuous J. 1992;2:36–9. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orkin F, Cohen M, Duncan P. The quest for meaningful outcomes. Anesthesiology. 1993;3:417–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dexter F, Aker J, Wright WA. Development of a measure of patient satisfaction with monitored anesthesia care: The Iowa Satisfaction with Anesthesia Scale. Anesthesiology. 1997;87:856–64. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199710000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brandi White Measuring Patient Satisfaction: How to Do It and Why to bother. A well-designed survey can help you improve your practice. The key? ‘Keep it simple,’ and act on what you learn. American Academy of Family Physicians. 1999 Jan [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karl WL. “What is a Likert Scale? East Carolin University. [last accessed on 2005 Oct 4]. Available from: https://www.core.ecu.edu/psyc/wuenschk/StatHelp/Likert.htm .

- 8.Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrical. 1951;16:297–334. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baroudi D, Nofal W. Patient Safety in Anesthesia. Internet J Health. 2009;8 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Letaief M, Bchir A, Mtiraoui A, Salem BK, Soltani MS. Translating patients concerns to prioritize Health care Interventions. Arch Public Health. 2002;60:329–39. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jossey-Bass . Through the patient's eyes. 2nd ed. San Francisco: 1993. pp. 19–43. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donald Ml, Halliburton JR, Preston JC. Evaluation of anesthesia patient satisfaction instruments. AANA J. 2004;72:211–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Auquier P, Blache JL, Colavolpe C, Eon B, Auffray JP, Pernoud N, et al. A scale of perioperative satisfaction for anesthesia: I--Construction and validation. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 1999;18:848–57. doi: 10.1016/s0750-7658(00)88192-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caljouw MA, van Beuzekom M, Boer F. Patient's satisfaction with perioperative care: Development, validation, and application of a questionnaire. Br J Anesth. 2008;100:637–44. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Myles PS, Williams DL, Handrata M, Anderson H, Weeks AM. Patient satisfaction after anesthesia and surgery: Result of prospective study of 11 811 patient. Br J Anesth. 2000;84:6–10. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bja.a013383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ward SE, Gorden D. Application of the American Pain society, Quality assurance standards. Pain. 1994;56:299–306. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)90168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fitzpatrick R. Survey of patient satisfaction: II-design a questionnaire and conducting a survey. BMJ. 1991;302:1129–32. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6785.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tong D, Chang F, Wong D. Predictive factors in global and anesthesia satisfaction in ambulatory surgical patients. Anesthesiology. 1997;87:856–64. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199710000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Canthain A, Walters SJ, Nicholl JP, Thomas KJ, Kirkham M. Use of evidence based leaflets to promote informed choice in maternity care: Randomized controlled trial in everyday practice. BMJ. 2002;324:643–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7338.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heidegger T, Husemann Y, Nuebling M, Morf D, Sieber T, Huth A. Patient satisfaction with anesthesia care: Development of a psychometric questionnaire and benchmarking among six hospitals in Switzerland and Austria. Br Anaesth. 2002;89:863–72. doi: 10.1093/bja/aef277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health organization bulletin –BT. 2008 Jul 7;86(2008):497–576. Nr. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shevde K, Panagopoulos G. A survey of 800 patients’ knowledge, attitudes and concerns regarding anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 1991;73:190–8. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199108000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klafta JM, Roizen MF. Current understanding of patients’ attitudes toward and preparation for anesthesia: A review. Anesth Analg. 1996;83:1314–21. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199612000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jenkins K, Grady D, Wong J, Correa R, Armanious S, Chung F. Post-operative recovery: Day surgery patients’ preferences. Br J Anaesth. 2001;86:272–4. doi: 10.1093/bja/86.2.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scott NB, Hodson M. Public perceptions of post operative pain and its relief. Anesthesia. 1997;52:438–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1997.122-az0116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beauregard L, Pomp A, Choiniere M. Severity and impact of pain after day surgery. Can J Anaesth. 1998;45:304–11. doi: 10.1007/BF03012019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gan TJ, Sloan F, Dear GD, El-Moalem HE, Lubrasky DA. How much are patients willing to pay to avoid post operative nausea and vomiting? Anesth Analg. 2001;92:393–400. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200102000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baroudi DN. Post operative pain management in children 2008. Internet J Health. 2008;7 [Google Scholar]