Abstract

Introduction:

During preoperative preparation, patients undergo investigations to detect asymptomatic diseases. The probability of finding significant abnormalities on such routine investigations is small, and these investigations unnecessarily increase costs of perioperative care. We evaluated current practices, compliance with national guidelines and costs of preoperative investigations at the National Hospital of Sri Lanka (NHSL).

Materials and Methods:

Patients undergoing elective surgery at the general surgical units of the NHSL from June to August 2010 were included in this study. The National Guidelines on Preoperative Investigations were the standard of assessment. Data on preoperative investigations were collected using an expert-validated pretested interviewer-administered questionnaire.

Results:

Sample size was 2,061 patients. Mean age of the patients was 46.7±15.8 years; males constituted 54.2% of the study population. Majority of the patients were ASA-I (68.5%) and surgical grade II (62.0%). Request for chest X-ray and prothrombin time / international normalized ratio least conformed to the guidelines. Only fasting blood sugar / random blood sugar demonstrated ‘good’ compliance (>70%) to the guidelines. An ‘acceptable’ compliance (50%-70%) was seen for electrocardiogram, blood grouping and full blood count. All other investigations demonstrated ‘poor’ compliance (<50%) with the guidelines. The total excess cost incurred due to non-recommended investigations during the study period of 3 months was Sri Lankan Rupees (LKR.) 1,324,860 to 2,044,210 (per patient LKR. 642.82-991.85). Intern house officers (IHOs) were involved in the planning of preoperative investigations in 2,001 patients (97.1%), followed by medical officeranesthesia / registrar-anesthesia (n=1,625; 78.8%), surgical registrars (n=190; 9.2%), consultant (n=70; 3.4%), senior registrar (n=46; 2.2%) and senior house officers (n=22; 1.1%). Non-recommended investigations were requested mostly by the IHOs and medical officer–anesthesia / registrar-anesthesia.

Conclusions:

Unnecessary preoperative investigations are common at our institution, leading to substantially excessive costs. There is ample opportunity to rationalize practices and reduce expenditure.

Keywords: Elective surgery, National Hospital of Sri Lanka (NHSL), preoperative assessment, Sri Lanka

INTRODUCTION

Prior to elective surgery, patients are pre-assessed to evaluate fitness for anesthesia and surgery. This assessment includes patients’ history, clinical examination and subsequent investigations. Preoperative investigations can be a valuable tool in the preparation of a patient for surgery, since appropriate preoperative treatment of unidentified diseases helps to minimize perioperative morbidity and mortality.[1] Many of these investigations are requested by inexperienced junior staff without guidance and rarely influence clinical management. Current literature has consistently demonstrated that ‘routine’ preoperative testing has little, if any, impact on perioperative outcomes, particularly in asymptomatic patients undergoing low-risk ambulatory surgery.[2–6] In addition, the overuse of investigations that are not indicated may increase patient morbidity due to over-treatment for borderline or false-positive results. This also leads to wastage of resources and considerable inconvenience to patients and health staff and increases financial costs to the patients and hospitals.[7]

In an attempt to control the costs and rationalize practices, a variety of agencies, including National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence, United Kingdom (NICE-UK);[8] and Canadian Anesthesiologists Society (CAS),[9] have published guidelines on preoperative test-ing. In the Sri Lankan context, the College of Anesthesiologists of Sri Lanka has published the National Guidelines on Preoperative Investigations, which have been endorsed by the Ministry of Health Care and Nutrition, Sri Lanka.[10] A recent study done at the National Hospital of Sri Lanka comparing compliance of preoperative investigations with the NICE-UK guidelines showed that a large number of preoperative investigations were unnecessary and caused a significant financial burden.[11]

There are no published studies from Sri Lanka evaluating the preoperative testing practices and their cost-effectiveness. The primary objective of the present study was to understand the current preoperative testing practices followed at the National Hospital of Sri Lanka (NHSL), evaluate their cost-effectiveness and determine if these testing practices were compliant with the national guidelines. Secondary objectives were identification of the source of testing orders non-compliant with the guidelines and evaluation of excess costs incurred due to unnecessary preoperative investigations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population and sampling

This prospective study was conducted among all patients undergoing elective surgery at the general surgical units of the NHSL over a period of 3 months from June to August 2010. The NHSL is a tertiary care unit situated in Colombo with an approximate bed capacity of 3,000.[12] The specialized surgical units, including neurosurgery, cardio-thoracic surgery, ENT surgery, genitourinary surgery, orthopedic surgery, plastic surgery and vascular surgery, were not included in the study

Two teams of doctors are involved in preoperative management of patients. The surgical team comprises of a consultant surgeon, a senior registrar (SR), registrars, senior house officers (SHOs) and intern house officers (IHOs). The anesthesia team comprises of consultant anesthesiologist, medical officer–anesthesia (MO-anesthesia) and registrar-anesthesia. The anesthesia team visits the respective surgical units for preoperative assessment.

Study instrument and standards of assessment

Data on preoperative investigations were collected using a expert-validated pretested interviewer-administered questionnaire. The National Guidelines on Preoperative Investigations were used as the standard of assessment. Details of evidence, method and guidance can be found on their web-site.[10] The guidelines take into account the patient's age, the complexity of the surgery, comorbid diseases and the drugs the patient is on.

The following common preoperative investigations were evaluated: chest X-ray (CXR), electrocardiogram (ECG), full blood count (FBC), prothrombin time / international normalized ratio (PT/ INR), fasting blood sugar / random blood sugar (FBS/ RBS), renal function tests (RFTs, including blood urea, serum creatinine and serum electrolytes), AST/ ALT, blood grouping and cross-matching and 2D echocardiogram (2D echo). The investigations were classified into three categories depending on compliance to guidelines: a) ‘good’ compliance, if compliance was >70%; b) ‘acceptable’ compliance, i.e., compliance between 50% and 70%; and c) ‘poor’ compliance, i.e., compliance <50%.

The price of each investigation was obtained from 10 government and non-government institutions. To calculate the cost incurred for a non-recommended investigation, both minimum and maximum prices were used to obtain a cost range, as the prices of investigations varied between institutions.

Statistical analyses

Data were double-entered and cross-checked for consistency. Analysis was done using the SPSS version 16 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Categorical data were described as proportions. Continuous data were described using mean and standard deviation and compared using unpaired Student t test. In all analyses, a P value of <.05 was considered statisti-cally significant.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics Review Committee of the National Hospital of Sri Lanka. The permission to conduct the study was obtaiend from the Director of the NHSL and consultants in charge of the general surgical units. Data were collected from bed head tickets, and no personal details of patients were collected.

RESULTS

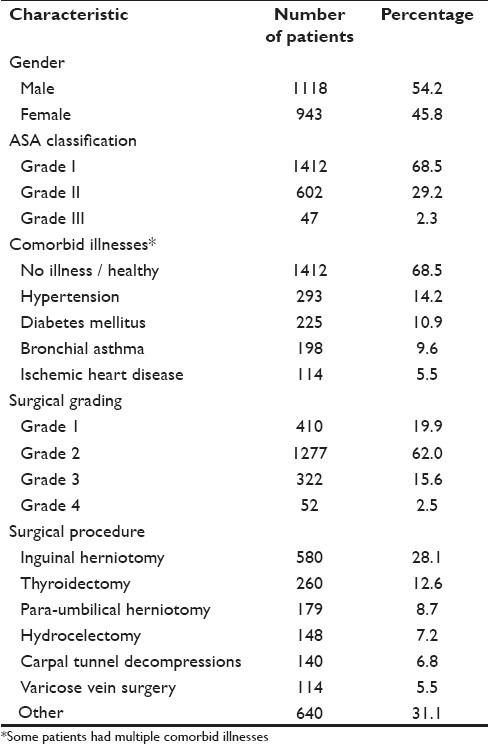

During the study period, records of 2,061 patients were analyzed. Mean age of the patients was 46.7±15.8 (SD) years, and males constituted 54.2% of the study population (n=1,118). Majority of the patients had no comorbid illnesses and thus belonged to the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade I (n=1,412; 68.5%). Most patients underwent intermediate grade (grade II) surgical procedures (n=1,277; 62.0%). Sample characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population

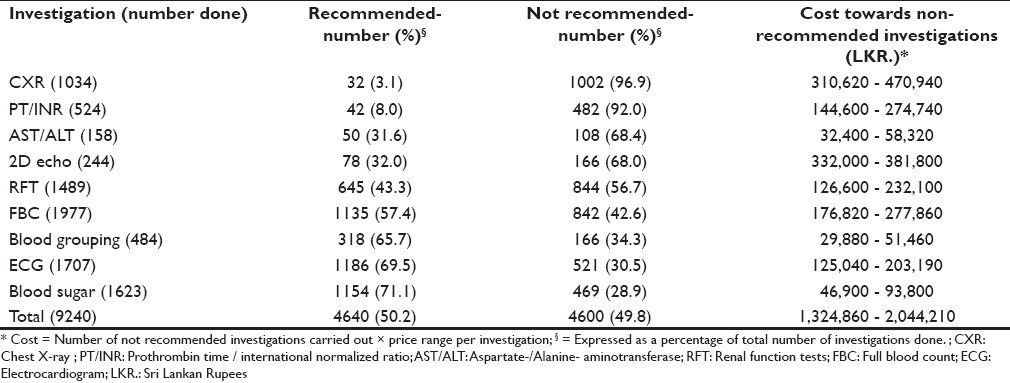

The mean number of investigations requested per patient per surgery for the entire study population (all patients included in the study) was 4.4±1.8; and for those who underwent surgery grade 1, grade 2, grade 3 and grade 4, it was 3.1±1.5, 4.3±1.6, 6.4±1.1, and 7.5±1.1, respectively. The FBC was the most requested investigation (n=1,977; 95.9%), followed by ECG (n=1,709; 82.9%), FBS/ RBS (n=1,623; 78.7%), RFTs (n=1,489; 72.2%), CXR (n=1,034; 50.2%), PT/ INR (n=524; 25.4%), blood grouping (n=484; 23.5%), 2D echo (n=244; 11.8%) and AST/ ALT (n=158; 7.7%). For each investigation, compliance/ non-compliance to guidelines and the excess cost incurred due to non-compliance with guidelines were evaluated. Request for CXR and PT/ INR least conformed to the guidelines [Table 2]. Only FBS/ RBS demonstrated ‘good’ compliance (>70%) to the national guidelines. An ‘acceptable’ compliance (50%-70%) was seen for ECG, blood grouping and FBC. All other investigations demonstrated ‘poor’ compliance (<50%) with the recommendations.

Table 2.

Investigations done compared with local guidelines, along with cost of non-recommended investigations

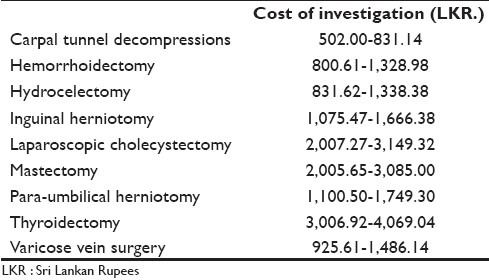

Among the investigations non-compliant with the guidelines, FBC, CXR and 2D echo were the ones that cost the most [Table 2]. The total excess cost incurred due to non-recommended investigations during the study period of 3 months was LKR. 1,324,860 to 2,044,210 (per patient LKR. 642.82-991.85). The annual excess expenditure incurred for the general surgical units by the NHSL was extrapolated to be LKR. 5,299,440 to 8,176,840. The costs incurred on investigations for certain index elective surgeries at general surgical units were also calculated [Table 3].

Table 3.

Mean costs of index elective surgeries performed at the general surgical units

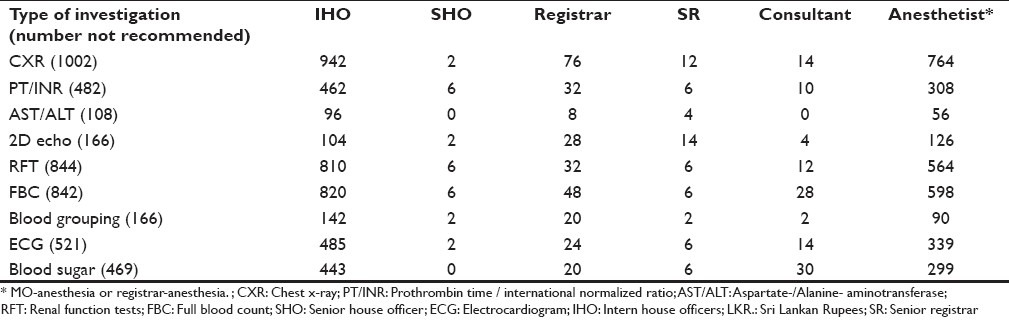

IHOs were involved in the ordering of preoperative investigations in 2,001 (97.1%) patients, followed by MO-anesthesia / registrar-anesthesia (n=1,625; 78.8%), surgical registrars (n=190; 9.2%), consultant (n=70; 3.4%), senior registrar (n=46; 2.2%) and SHOs (n=22; 1.1%). Investigations that did not comply with the guidelines were requested in most instances by the IHOs or the MO-anesthesia / registrar-anesthesia [Table 4]. The number of investigations done showed a significant (P<0.001) positive correlation with patient's age (r=0.378), surgical grade (r=0.564) and ASA grade (r=0.216).

Table 4.

The numbers of investigations non-compliant with the guidelines classified according to the personnel recommending it

DISCUSSION

This first comprehensive report on preoperative investigation practices and costs in Sri Lanka showed that a majority of the study population had no systemic disease by ASA classification and most of the patients underwent intermediate-grade surgical procedures. Preoperative assessment is thought to be essential in minimizing morbidity due to surgery. It helps identify patients who may benefit from preoperative treatment and those who should not undergo surgery. However, a recent meta-analysis has demonstrated that the power of preoperative tests to predict adverse postoperative outcomes in asymptomatic patients, such as in the present study population, is of very small magnitude or nil.[13] However, the same tests may have greater predictive power in defined high-risk populations.

In the present study, FBC, ECG and FBS/ RBS were requested in over 70% of the patients. A FBC is generally requested to detect anemia, which may place the individual at risk from anesthesia or surgery. However, ‘routine’ screening of FBC contributes little to the patient's management.[13] Most cases of anemia, which is significant enough to alter patient management, can be detected by a full history and examination.[14] One of the leading causes of death following surgery is cardiac events.[15] Thus a single resting ECG may be of some value in preoperative screening for cardiac disease. However, studies have consistently demonstrated that ‘routine’ investigations may be worthwhile only in older patients.[16] Diabetes mellitus has reached epidemic proportions in SriLanka;[17] in the present study, 1 in 10 patients was on treatment for diabetes mellitus. Therefore, FBS/ RBS level may be a reasonable test to be done considering the present epidemiological trends. In addition, the compliance with guidelines for blood sugar testing was over 70%; the local guidelines allowing sufficient leeway considering the present epidemiological trends could be the reason for this high compliance.

A majority of investigations, with the exception of FBS/ RBS, demonstrated either only an ‘acceptable’ or a ‘poor’ level of compliance to the national guidelines. This is in keeping with the previously reported data obtained using the NICE-UK guidelines.[11] CXR (96.9%) and PT / INR (92.0%) were the two investigations least compliant to the guidelines. The prevalence of smoking and associated illnesses is high among Sri Lankan males.[18] However, according to national guidelines, a routine CXR is not indicated on any patient with stable disease of the respiratory system, whatever his or her age.[10] This disparity between high prevalence and guideline recommendations could be a probable reason for the CXR demonstrating very poor adherence to the guidelines. The national guidelines recommend patients with liver disease, including those with suspected alcohol abuse, to have a PT/ INR done as part of the preoperative investigations.[10] Studies have demonstrated, that in Sri Lanka 39% of men in urban areas consume alcohol.[18] However, many of them do not admit to have indulged in alcohol consumption, when questioned. Thus there is a tendency among Sri Lankan doctors to do PT/ INR in almost all patients undergoing intermediate and major surgery, which could be a probable reason for the high rate of non-compliance.

Junior members of the team with less experience, such as the IHOs, SHOs and MO-anesthesia / registrar-anesthesia, were involved in planning investigations in most patients and hence they were involved in requesting most number of non-recommended investigations. Involvement of senior members of the team in planning investigations was minimal. Previous studies have consistently demonstrated that selective ordering of preoperative investigations by specialist anesthesiologists reduces the number and total cost of tests.[19] A substantial excess cost was incurred by the hospital on unnecessary preoperative evaluation. This study was limited to the general surgical units of the hospital; thus the actual total expenditure incurred by the hospital towards unnecessary preoperative investigations could be substantially higher when other surgical units are also included.

The results of this study suggest that unnecessary laboratory testing during preoperative preparation of patients is still common. However, achieving a compliance of 100% would be a practical impossibility. Thus a compliance of >70% would be an acceptable and feasible level. In the present study, with the exception of FBS/ RBS, all other investigations failed to achieve this level of compliance. Hence there is ample opportunity to rational-ize testing practice and decrease testing-related costs. We recommend the following remedies to improve the current situation: (1) education of the surgical and anesthetic teams on current practices and excess cost incurred, (2) adoption of guidelines on preoperative investigations with the aim of modifying existing practices and (3) re-evaluation after adopting the guidelines.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Roizen M. Preoperative patient evaluation. Can J Anaesth. 1989;36:S13–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03005321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turnbull JM, Buck C. The value of preoperative screening investigations in otherwise healthy individuals. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147:1101–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson H, Jr, Knee-Ioli S, Butler TA, Munoz E, Wise L. Are routine preoperative laboratory screening tests necessary to evaluate ambulatory surgical patients? Surgery. 1988;104:639–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Narr BJ, Hansen TR, Warner MA. Preoperative laboratory screening in healthy Mayo patients: Cost-effective elimination of tests and unchanged outcomes. Mayo Clin Proc. 1991;66:155–9. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)60487-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Velanovich V. The value of routine preoperative laboratory testing in predicting postoperative complications: A multivariate analysis. Surgery. 1991;109:236–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perez A, Planell J, Bacardaz C, Hounie A, Franci J, Brotons C, et al. Value of routine preoperative tests: A multicentre study in four general hospitals. Br J Anaesth. 1995;74:250–6. doi: 10.1093/bja/74.3.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mendis A, Jayasunderabandara JMW, Atukorala SD. Ministry of Health. Sri Lanka: National Guidelines on Preoperative Investigations; 2005. How to make best use of a diagnostic laboratory. [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Collaborating Centre for Acute Care. CG3 Preoperative tests, the use of routine preoperative tests for elective surgery: evidence, methods and guidance - Full guideline. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. [Last accessed on 2010 Aug 20]. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/page.aspx?o=77801 .

- 9.Canadian Anesthesiologists Society. Guidelines to the practice of anesthesia. The pre-anesthetic period. 2004. [Last accessed on 2010 Aug 20]. Available from: http://www.cas.ca/members/sign_in/guidelines/practice_of_anesthesia/default.asp?load=preanesthetic .

- 10.The College of Anaesthesiologists of Sri Lanka. The national guidelines on preoperative investigations. [Last accessed on 2010 Aug 20]. Available from: http://www.health.gov.lk/National%20Guidelines.htm .

- 11.Ranasinghe P, Perera YS, Abayadeera A. Preoperative investigations in elective surgery: Practices and costs at the National Hospital of Sri Lanka. Sri Lankan Journal of Anesthesiology. 2010;18:29–35. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ministry of Health Care and Nutrition, Sri Lanka. Ministry of Health Care and Nutrition, Sri Lanka. Health Institutions by Type. 2009. [Last accessed on 2010 Aug 20]. Available from: http://203.94.76.60/nihs/BEDS/2009%20Total%20Beds.pdf .

- 13.Munro J, Booth A, Nicholl J. Routine preoperative testing: A systematic review of the evidence. Health Technol Assess. 1997;1:1–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barnard NA, Williams RW, Spencer EM. Preoperative patient assessment: A review of the literature and recommendations. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1994;76:293–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van der Merwe WL, Coetzee AR. Pre-operative assessment and management of the patient with ischaemic coronary artery disease in non-cardiac surgery. S Afr J Surg. 1992;30:99–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sommerville TE, Murray WB. Information yield from routine pre-operative chest radiography and electrocardiography. S Afr Med J. 1992;81:190–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katulanda P, Sheriff MH, Matthews DR. The diabetes epidemic in Sri Lanka - a growing problem. Ceylon Med J. 2006;51:26–8. doi: 10.4038/cmj.v51i1.1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Silva V, Samarasinghe D, Gunawardena N. Alcohol and tobacco use among males in two districts in Sri Lanka. Ceylon Med J. 2009;54:119–24. doi: 10.4038/cmj.v54i4.1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Finegan BA, Rashiq S, McAlister FA, O’Connor P. Selective ordering of preoperative investigations by anesthesiologists reduces the number and cost of tests. Can J Anaesth. 2005;52:575–80. doi: 10.1007/BF03015765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]