Abstract

Background:

Ensuring adequate preoperative sedation and anxiolysis is essential, especially in pediatric surgery. Various drugs and routes of administration have been evaluated to determine the optimal method of sedation.

Materials and Methods:

We selected hundred preschool children undergoing elective surgery and sedated them with either intranasal midazolam or oral promethazine syrup in the preoperative period. They were assessed with respect to their levels of sedation till the period of mask placement for induction of general anesthesia.

Results:

Both groups had comparable heart rates, respiratory rates, sedation scores, and emotional scores at all points of assessment (P>0.05). However, intranasal midazolam had a significantly shorter onset of sedation as well as time to reach maximal sedation (P<0.001).

Conclusion:

We conclude that either drug may be used with ease in preschool children undergoing elective surgery.

Keywords: Intranasal midazolam, preschool children, promethazine, sedation

INTRODUCTION

The perioperative period can be a stressful time for children. Anxiety and separation from parents results in autonomic hyperactivity, dysarrhythmias, hypersalivation, breath holding, and laryngospasm under the initial effects of anesthesia.[1] There could even be negative behavioral manifestations for weeks or months following frightening induction room experiences.[2] Preoperative anxiety also activates the human stress response, leading to increased serum cortisol, epinephrine, and natural killer cell activity.[3,4] Stress leads to activation of the hypothalamic pituitary-adrenal axis, thereby increasing circulating glucocorticoids, and is associated with alterations of immune function and susceptibility to infection and neoplastic disease.[5] The human response to surgical stress is characterized by a series of hormonal, immunological, and metabolic changes that together constitute the “surgical stress response”.[6,7] Establishment of adequate preanesthetic sedation and amnesia for pre- and intra-operative events has thus assumed an important role in the anesthetic management of pediatric patients. There is still no entirely satisfactory way to ensure smooth induction of anesthesia in children. An ideal premedicant should have consistent, predictable results, good patient acceptance, and no side effects. Almost all the premedicant drugs available require an injection, administering a pill, transmucosal, or rectal administration of drugs. Midazolam has been found to be a good preanesthetic agent in preschool children and produces rapid sedation, anxiolysis with reduced postoperative vomiting.[8,9] Promethazine syrup, as a sedative agent in children, has withstood the test of time. It is a safe and effective drug with low complication and failure rates.[10,11]

The present study was undertaken to evaluate the efficacy of intranasally administered midazolam as compared to oral promethazine with respect to their preanesthetic sedative and calming effects in preschool children.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was conducted in a tertiary care hospital in western India over a period of 2 years. After obtaining permission from the hospital ethics committee, 100 preschool children between the ages of 6 months to 6 years, presenting for elective surgery under general anesthesia were included in the study. Informed consent for administering the medication was obtained from one of the child's parents. All children weighed less than 20 kg and conformed to class I and II of the ASA classification. All selected patients were subjected to preoperative anesthetic evaluation including, physical examination and relevant physical examinations. All patients were “nil by mouth” for solids and liquids up to 6 and 4 hours preceeding surgery, respectively.

The exclusion criteria were as follows:

Children having upper respiratory infections, rhinopharyngitis

History of drug allergies to the study drugs

Those requiring an intravenous anesthetic induction

Those unaccompanied by a responsible adult

The selected children were alternately chosen to receive either intranasal midazolam (preservative free) 0.3 mg/kg, 30 minutes prior to induction of general anesthesia (group M) or oral promethazine syrup 1 mg/kg, 90 minutes prior to induction of general anesthesia (group P). Intranasal midazolam was administered in the treatment room outside the operation theatres by the study anesthetist. The child was laid supine in the parent's lap with arms gently restrained by one parental hand and the other used to tilt the forehead backward by 15 degrees. The premedicant drug was administered with a 2-ml plastic syringe containing the appropriate volume of drug. Half the volume was administered into each nostril and the position was maintained for 60–90 seconds after which the child resumed his comfortable position. Oral promethazine was administered in the ward by the attending nurse, approximately 90 minutes prior to the time of the planned anesthetic induction.

A five-point sedation and four-point emotional scale (Gutstein et al, 1992)[12] were used to assess the patient's sedation and emotional levels. Both groups were assessed at 30, 25, 20, 15, 10, and 5 minutes prior to the planned administration time of general anesthesia. Final assessment was at the time of mask placement for anesthetic induction. Additional parameters studied included heart rate, respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation percentage (pulse oximetry) at these same intervals. Any side effects occurring in the pre-induction period in either arm were noted. All children were separated from their parents at the point of maximal sedation. The study anesthetist remained with the children throughout this period.

General anesthesia was induced with oxygen, nitrous oxide, and halothane via a face mask and intravenous access was established. Following this, additional drugs were used as per the requirements of the surgery and choice of the anesthetist.

Data were analyzed using SPSS software.

Evaluation scales (Gutstein et al., 1992)

Sedation scale:

Barely arousable (asleep, needs shaking or shouting to arouse)

Asleep (eyes closed but arouses to a soft voice or light)

Sleepy (eyes open, less active, withdrawn)

Awake

Agitated

Emotional state scale:

Calm

Apprehensive

Crying

Thrashing

RESULTS

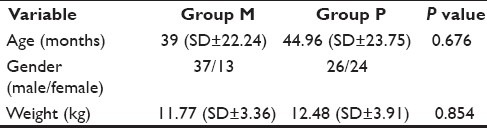

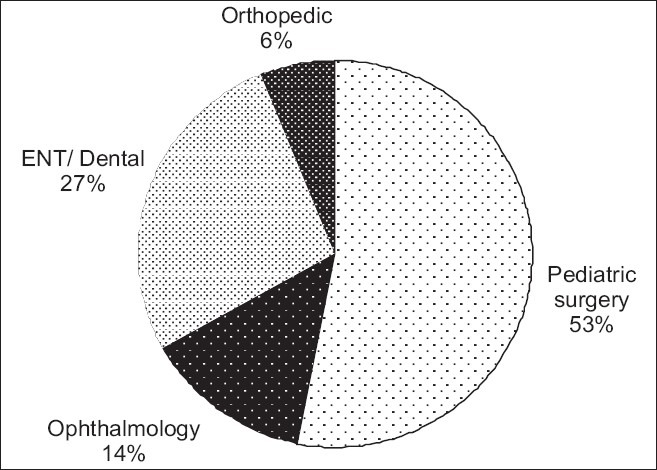

Hundred preschool children presenting for elective surgery under general anesthesia were studied. There were no significant differences between the groups in terms of age, sex, or weight distribution [Table 1]. Most patients were undergoing pediatric surgical procedures (53%), orthopedic surgeries (27%), and ophthalmologic surgeries (14%) [Figure 1].

Table 1.

Demographic data

Figure 1.

Distribution of cases (with respect to surgical procedures)

The mean onset of sedation (time from administration of drug to onset of sedation) was 4.86 (SD±1.385) minutes in group M and 65.66 (SD±14.927) minutes in group P. Maximal sedation was obtained at 12.70 minutes (SD±2.705 minutes) in group M and 82 minutes (SD±14.392 minutes) in group P. Thus, there was a significant reduction in both, the time to onset of sedation and time to maximal sedation (P< 0.001) in the midazolam group.

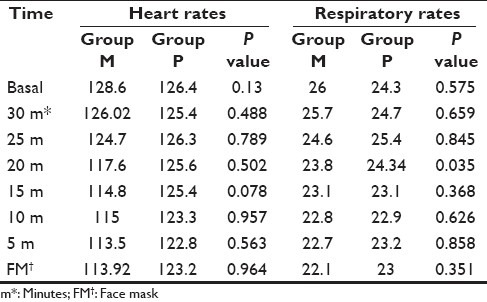

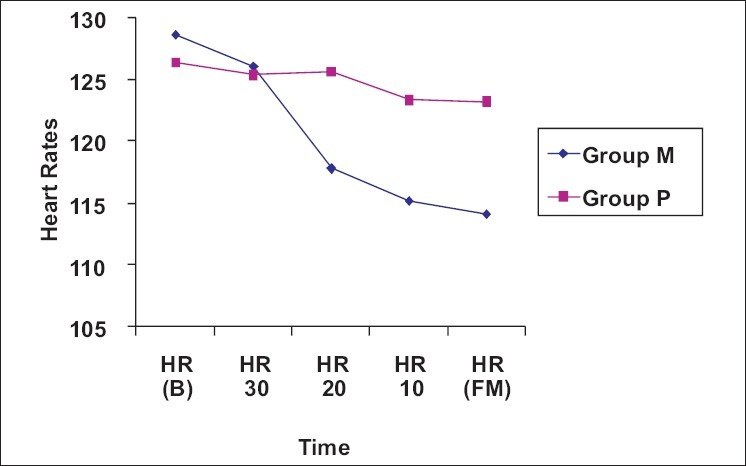

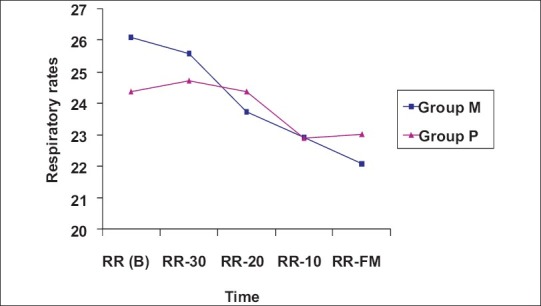

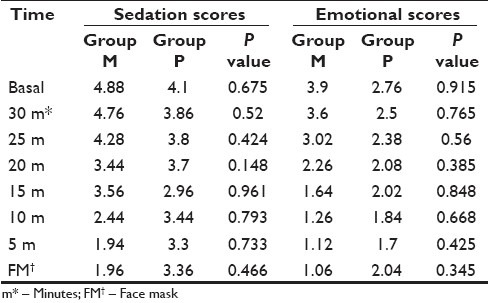

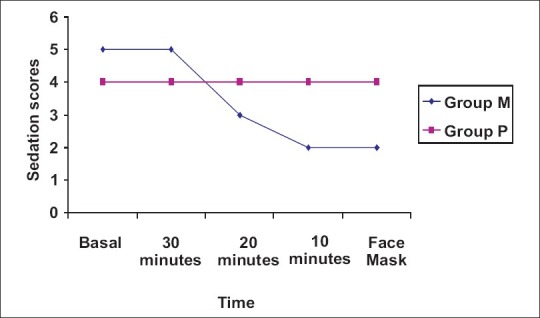

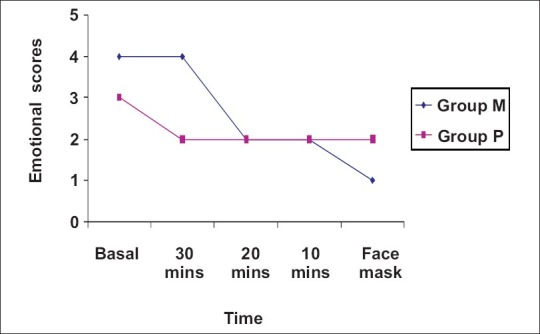

Both groups were found to be comparable with respect to heart rate and respiratory rate changes from 30 minutes prior to induction of anesthesia to placement of face mask [Table 2] At 20 minutes prior to mask placement, the respiratory rate score in the midazolam group was significantly lower than the same in the promethazine group (P value 0.035). However, as this was an isolated difference, this was not considered as a significant finding. The average heart rates fell from 128.62 beats/minute (baseline) to 113.92 beats/minute at placement of face mask in group M while in group P, average heart rates fell from 126.42 beats/minute to 123.28 beats/minute during the same observation periods [Figure 2]. Average respiratory rates fell from 26.08 per minute to 21.12 per minute in group M and from 24.30 to 23.02 in group P [Figure 3]. Sedation and emotional scores were likewise found to be similar in the two groups [Table 3]. In group M, sedation scores fell from a mean of 4.88 (SD±0.328) to 1.96 (SD±0.402) while in group P sedation scores fell from 4.10 (SD±0.614) to 3.36 (SD±0.827) [Figure 4]. Emotional scores fell from 3.90 (SD±0.303) to 1.06 (SD±0.240) in group M and from 2.76 (SD±0.870) to 2.04 (SD±0.699) in group P during the corresponding periods [Figure 5].

Table 2.

Mean and standard deviations of heart rates and respiratory rates in the two groups

Figure 2.

Average heart rate changes in two groups

Figure 3.

Average respiratory rates changes in the two groups

Table 3.

Comparison of sedation and emotional scores in the two groups

Figure 4.

Average sedation scores in the two groups

Figure 5.

Average emotional scores in the two groups

No patient developed bradycardia or hypoxemia (oxygen saturation <95%) after the administration of preoperative medication at any point of observation.

DISCUSSION

Surgery and anesthesia are distressing periods for most children. Pharmacological medications are often used in them to alleviate the stress and fear of surgery and also help to ease child–parent separation so as to promote a smooth induction of anesthesia. Several drugs and drug combinations have been tried in an attempt to find the best sedative agent and the best route of administration of these drugs in children. A premedicant must have an acceptable, atraumatic mode of administration and not add to the existing stress of the child. Currently, the most commonly used sedative premedicants include midazolam, ketamine, transmucosal fentanyl, and meperidine. McCann and Kain reported that the majority of children in the United States are premedicated most commonly via the oral route, followed by the intranasal route, the intramuscular route, and the rectal route.[13]

Midazolam has generally been administered in the form of intravenous, intramuscular, or oral drug. There have been several studies comparing the efficacy of midazolam with other sedative-hypnotics for preanesthetic sedation. Reinhart et al. compared intramuscular midazolam with diazepam and placebo in patients undergoing urological interventions and reported that the former had a more rapid onset of sedation, produced a more profound sedation and amnesia than the other groups.[14] In another study comparing the effects of oral clonidine with oral midazolam in children undergoing tonsillectomy, the midazolam group fared better with lower anxiety scores on separation from parents and at induction, lesser postoperative pain scores and overall better satisfaction among parents with respect to the children's preoperative experience.[15] Singh et al. compared the sedative effects of oral midazolam with other sedatives (oral triclofos and oral promethazine) in children presenting for short dental procedures and concluded that oral midazolam produced the best levels of conscious sedation in these patients.[16]

The transmucosal route is a relatively newer form of premedicant drug delivery as compared to the other commonly administered routes. A study of plasma concentrations and sedation scores following nebulized versus intranasal (direct instillation) midazolam among healthy volunteers suggests that the comparative bioavailability of midazolam was 1:2.9 respectively with the former producing better sedation and visual analogue scores.[17] Several studies have compared the various routes of administration of midazolam and found that midazolam when administered intranasally produced a more rapid sedation than when administered through other routes.[1,14] However in another study by Lam et al., intramuscular administration of midazolam produced better sedation and less movement at venipuncture than intranasal midazolam.[18] Lejus et al. reported that intranasal midazolam is an effective and rapid route of premedication, yet one that is poorly accepted by patients.[19] In a study on 40 children requiring conscious sedation, Shashikiran et al. found that both the intranasal and intramuscular routes of midazolam produced effective and comparable sedation with equal efficacy and safety profiles. However, the intranasal route showed a significantly faster pharmacodynamic profile in terms of faster onset, peak, and recovery times.[20] Wilton et al. compared two doses of intranasal midazolam with placebo (intranasal normal saline) in children and concluded that intranasal midazolam at a dose of 0.2 mg/kg produced sedation comparable with a dose of 0.3 mg/kg and both were better than placebo.[21] Slover et al. compared intranasal midazolam administered as drops and with an intranasal spray device in surgical day case children and concluded that the drug was equally effective in both groups but acceptability was poor.[22]

Our study compared the preanesthetic sedative effects of intranasal midazolam with oral promethazine in a hundred preschool children presenting for elective surgical procedures and found that intranasal midazolam produced sedation and anxiolysis comparable with oral promethazine. Fifty children in either group were administered either intranasal midazolam or oral promethazine. No child in either group had significant bradycardia or hypoxemia (SpO2 <98%) from the time of administration till application of face mask. Sedation and emotional scores between the groups were similar in both groups with no statistical difference at any period from 30 minutes prior to induction of anaesthesia to the application of face mask. Similarly, heart rates and respiratory rates were similar in both groups at all points of comparison. Intranasal midazolam produced a more rapid onset of sedation (average 4.86 minutes) and time to maximal sedation was only 12.70 minutes with this drug. In comparison, oral promethazine took longer to act (average onset at 65.66 minutes) with maximum sedation at 82 minutes.

We noted that the intranasal route of midazolam administration was uncomfortable to most children and it produced a stinging sensation when administered.

There were some limitations to our study. The study was not blinded, either to the observer or to the person administering the drug. Since the intranasal drug was administered in the operation theatre setting, the ambience itself may have added to the distress in some children while oral promethazine was administered in the ward, a less threatening environment for the child.

We conclude that intranasal midazolam produces sedation and anxiolysis equivalent to oral promethazine in preschool children undergoing surgery. Both are relatively easy to administer and do not require any additional equipment. The rapid onset and shorter duration to maximal sedation of intranasal midazolam is an additional advantage which makes the drug useful, particularly in the outpatient setting.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Malinovsky JM, Lejus C, Populaire C, Lepage JY, Cozian A, Pinaud M. Premedication with midazolam in children.Effect of intranasal, rectal and oral routes on plasma concentrations. Anaesthesia. 1995;50:351–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1995.tb04616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Politis GD. Pediatric anesthesia handbook. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2002. Preanesthetic sedation for pediatric patients lacking intravenous access; pp. 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kain Z, Sevarino F, Rinder C. The preoperative behavioral stress response: does it exist? Anesthesiology. 1999;91:A742. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chrousos GP, Gold PW. The concepts of stress and stress system disorders.Overview of physical and behavioral homeostasis. JAMA. 1992;267:1244–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ader R, Cohen N, Felten D. Psychoneuroimmunology: Interactions between the nervous system and the immune system. Lancet. 1995;345:99–103. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chernow B, Alexander HR, Smallridge RC, Thompson WR, Cook D, Beardsley D, et al. Hormonal responses to graded surgical stress. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147:1273–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weissman C. The metabolic response to stress: An overview and update. Anesthesiology. 1990;73:308–27. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199008000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kain ZN, Hofstadter MB, Mayes LC, Krivutza DM, Alexander G, Wang SM, et al. Midazolam: Effects on amnesia and anxiety in children. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:676–84. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200009000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coté CJ, Cohen IT, Suresh S, Rabb M, Rose JB, Weldon BC, et al. A comparison of three doses of commercially prepared oral Midazolam syrup in children. Anesth Analg. 2002;94:37–43. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200201000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sadove MS, Frye TJ. Preoperative sedation and production of a quiescent state in children.Promethazine-meperidine-scopolamine sedation. J Am Med Assoc. 1957;164:1729–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.1957.02980160001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cook BA, Bass JW, Nomizu S, Alexander ME. Sedation of children for technical procedures: Current standard of practice - Clin pediatr. 1992;31:137–42. doi: 10.1177/000992289203100302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gutstein HB, Johnson KL, Heard MB, Gregory GA. Oral ketamine preanesthetic medication in children. Anesthesiology. 1992;76:28–33. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199201000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCann ME, Kain ZN. The management of preoperative anxiety in children: An update. Anesth Analg. 2001;93:98–105. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200107000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reinhart K, Dallinger-Stiller G, Dennhardt R, Heinemeyer G, Eyrich K. Comparison of midazolam, diazepam and placebo I.M. as premedication for regional anaesthesia. A randomized double-blind study. Br J Anaesth. 1985;57:294–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/57.3.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fazi L, Jantzen EC, Rose JB, Kurth CD, Watcha MF. A Comparison of oral clonidine and oral midazolam as preanesthetic medications in the pediatric tonsillectomy patient. Anesth Analg. 2001;92:56–61. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200101000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh N, Pandey RK, Saksena AK, Jaiswal JN. A comparative evaluation of oral midazolam with other sedatives as premedication in pediatric dentistry. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2002;26:161–4. doi: 10.17796/jcpd.26.2.j714x4795474mr2p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCormick AS, Thomas VL, Berry D, Thomas PW. Plasma concentrations and sedation scores after nebulized and intranasal midazolam in healthy volunteers. Br J Anaesth. 2008;100:631–6. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lam C, Udin RD, Malamed SF, Good DL, Forrest JL. Midazolam premedication in children: A pilot study comparing intramuscular and intranasal administration. Anesth Prog. 2005;52:56–61. doi: 10.2344/0003-3006(2005)52[56:MPICAP]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lejus C, Renaudin M, Testa S, Malinovsky JM, Vigier T, Souron R. Midazolam for premedication in children: nasal vs.rectal administration. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 1997;14:244–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2346.1997.00013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shashikiran ND, Reddy SV, Yavagal CM. Conscious sedation-An artist's science! An Indian experience with midazolam. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2006;24:7–14. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.22830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilton NC, Leigh J, Rosen DR, Pandit UA. Preanesthetic sedation of preschool children using intranasal midazolam. Anesthesiology. 1988;69:972–5. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198812000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Slover R, Dedo W, Schlesinger T, Mattison R. Use of intranasal midazolam in preschool children. Anaesth and Analgesia. 1990;70:377. [Google Scholar]