Abstract

Objectives:

To compare the effectiveness of oral nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and locally injectable steroid (methylprednisolone) in the treatment of plantar fasciitis.

Materials and Methods:

One hundred and twenty subjects with unilateral plantar fasciitis were recruited and randomly allocated to two study groups. Group I (NSAIDs group) (n=60) received oral tablet diclofenac (50 mg) and paracetamol (500 mg) twice a day (BD) along with tab. ranitidine 150 mg BD. Group II (injectable steroid group) (n=60) received injection of 1 ml of methylprednisolone (Depomedrol) (40 mg) and 2 ml of 0.5% bupivacaine into the inflammed plantar fascia. Pain intensity was measured using 10 cm visual analog scale (VAS). Subjects were evaluated clinically before, and 1 week, 2 weeks, 4 weeks, and 8 weeks (2 months) after the initiation of treatment in both the groups. The outcome was assessed in terms of VAS score and recurrence of the heel pain.

Statistical Analysis Used:

“Z” test and Chi-square test were used wherever applicable.

Results:

Pain relief was significant after steroid injection (P<0.001) and the improvement was sustained. The recurrence of heel pain was significantly higher in the oral NSAIDS group (P<0.001).

Conclusion:

Local injection of steroid is more effective in the treatment of plantar fasciitis than oral NSAIDs.

Keywords: Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, plantar fasciitis, steroid injection, visual analog scale

INTRODUCTION

Plantar fasciitis is the one of the most common causes of painful heel in adults. It is assumed to be caused by inflammation and is typically precipitated by biomechanical stress. It is very difficult to treat this condition as the causation is not exactly diagnosed.

Plantar fascia is a broad band of fibrous tissue which originates from the anteromedial plantar aspect of the calcaneal tuberosity and inserts through several slips into the plantar aspects of the metatarsophalangeal joints, the flexor tendon sheaths, and the bases of the proximal phalanges of the digits. Athletic population has a high frequency of plantar fasciitis[1] and in the non-athletic population it is most frequently seen in weight bearing occupations.

Excessive pulling and stretching of plantar fascia either from excessive exercise or overuse, repeated trauma, aging, obesity, poor fitting shoe gear or poor foot alignment while running or prolong standing, produce microscopic tear of collagen or cystic degeneration in the origin of plantar fascia causing pain and inflammation.

The classic presentation of plantar fasciitis is pain on the sole of foot at the inferior region of the heel which is particularly worse with the first step taken on rising in the morning.

Numerous treatment measures have been used for plantar fasciitis, but there is no definitive treatment. Non surgical techniques include orthoses, stretching, splinting, taping, topical medications with or without iontophoresis, oral nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medications (NSAIDs), extra corporeal shock wave therapy, laser, percutaneous injections with steroid, botulinum toxin type A, autologous blood or platelet rich plasma.[2] Surgical option includes plantar fascia release, ultrasound guided needle fasciotomy, coablation surgery (topaz procedure).

The present study was undertaken with the intention to compare the effectiveness of NSAIDs and injectable steroid in conjunction with conventional supportive measures in the treatment of plantar fasciitis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This randomized, prospective, comparative study was conducted at the pain clinic of a tertiary level health care center over a period of nine months. After obtaining institutional ethical committee clearance and patients′ written informed consent, 120 adult patients, aged between 25-60 years, without any significant systemic disorder (The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade I and II), of both sexes, with unilateral plantar fasciitis of less than three months duration, without any prior proper treatment, with moderate to severe intensity of pain (visual analog scale (VAS) score 5–9 in 10 cm scale) and willing to be in follow-up regularly for two months, were enrolled for the study.

Subjects selected for the study were randomly allocated into two groups - group I (NSAIDs group) who were prescribed oral tablet diclofenae (50 mg) and paracetamol (500 mg) - one tab. twice a day along with tab. ranitidine (150 mg) - one tab. twice a day for 4 weeks and group II (injectable steroid group) in whom a single injection of 40 mg (1 ml) of methylprednisolone (Depomedrol) and 2 ml of 0.5% bupivacaine was injected into the tender most point of inflammed plantar fascia. For this purpose, randomization was done by allocating subjects with odd number to group I and even number to group II.

The group II patients were placed in the lateral recumbent position with the affected side down. The medial aspect of the foot was identified and soft tissue just distal to the calcaneous was palpated to locate the point of maximal tenderness or swelling where a 25-gauge, 1.5 inch needle was inserted perpendicular to the skin. The needle was directed down past the midline of the width of the foot. Methylprednisolone (Depomedrol) was injected slowly and evenly through the middle one third of the width of the foot while the needle was being withdrawn. Injection through the base of the foot into the fat pad was avoided. These patients were advised to apply ice locally and avoid strenuous activity involving the injected region for at least 48 hours and to start stretching exercises after 1 week of local steroid injection.

All the subjects in both the groups were advised to use soft heel foot wear, not to stand for long time, and not to walk bare foot.

All patients were familiarized with 0-10 cm visual analogue scale (VAS) for pain; 0 equal to “no pain” and 10 equal to “worst possible pain”. In both groups, pain intensity was measured before treatment, and 1 week, 2 weeks, 4 weeks, and 8 weeks (2 months) after the initiation of the treatment. The recurrence or increase in severity of heel pain was also assessed after 2 months of initiation of treatment. Complications, if any, occurred in any of the groups were also noted.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was done by the graph pad prism software 4 version and also manually which was done to cross check the outcomes. Sample size was decided on consultation with the statistician: Fifty was the smallest number in each group, where any results could be statistically significant (with power of 80%). Hence sample size of 60 (sixty) was selected for both the groups. Statistical measures such as “Z” test and Chi-square test were used to analyze the data. Results were reported as mean±standard deviation (SD). The results were considered to be statistically significant at the 5% critical level (P<0.05).

RESULTS

All the patient parameters and the results from the two groups (group I and group II) were entered in the pre-designed study pro forma sheet.

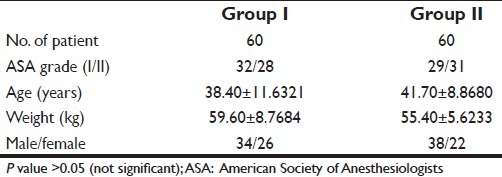

There was no significant difference in demographic profile for both the groups [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic profile of groups (mean±SD)

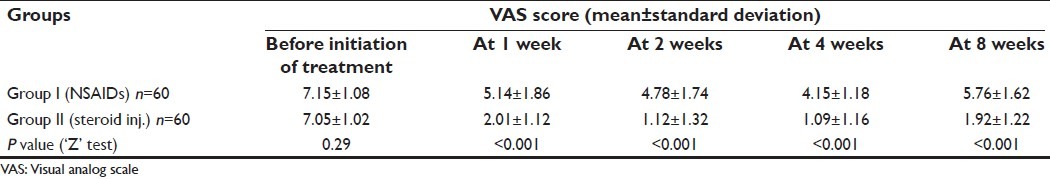

Statistically significant reduction in heel pain was seen in group II patients, as average VAS score improved from 7.05±1.02 at the initiation of treatment to 2.01±1.12 at 1 weekand 1.12±1.32 at 2 weeks. The improvement was sustained throughout the study; at 2 months, the average VAS score was 1.92±1.22 [Table 2].

Table 2.

Pain intensity (mean change in VAS score)

In group I patients, after initial improvement in average VAS score (at 1-week outcome measure 5.14±1.86 from basal VAS score of 7.15±1.08), no statistically significant reduction in VAS score was seen throughout the study. Infact, VAS score increased after discontinuation of oral NSAIDs as 2 month outcome measure showed average VAS score of 5.76±1.62 [Table 2].

The P value for VAS scores before the initiation of treatment for both groups was >0.1 and at 1 week was <0.001, at 2 week (<0.001), at 4 weeks (<0.001), and at 2 months was (<0.001), which showed a highly significant statistical difference in VAS scores throughout the study period between the two study groups [Table 2].

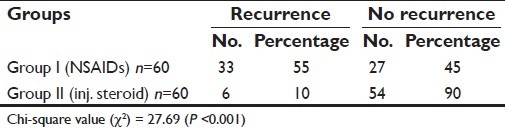

The recurrence of heel pain was significantly higher in group I (33/60 i.e. 55%) than that of group II (6/60 i.e. 10%) (P<0.001) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Recurrence (or increase in severity) of heel pain after 2 months

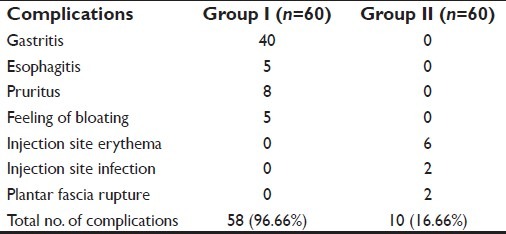

Occurrence of complications was more in group I patients (58/60 i.e. 96.66%) as compared to group II patients (10/60 i.e. 16.66%; only 2 patients presented with plantar fascia rupture) [Table 4].

Table 4.

Occurrence of complications

DISCUSSION

Plantar fasciitis is an inflammatory condition and the use of NSAIDs and local steroid injection are both logical and effective modalities for symptom relief. In our study, we intended to investigate that which would be a better treatment option for plantar fasciitis among these two.

In this study, it was found that a single local injection of steroid with local anesthetic caused statistically significant relief in heel pain and improvement in VAS score throughout the study period as compared to oral NSAIDs therapy (P<0.001). A double-blind randomized controlled trial by Crawford et al.,[3] in 106 patients with heel pain at a rheumatology clinic concluded that a statistically significant reduction in pain was detected at 1 month (P=0.02) in favor of steroid injection. As evidenced by Gudeman et al.,[4] in a study on 40 patients, iontophoresis of dexamethasone for plantar fasciitis should be considered when more immediate results are needed. Other studies showed that when more conservative management was unsuccessful, steroid injection was a preferred option.[5–7] Studies[6] have found steroid treatments to have a success rate of 70% or more.

The recurrence of heel pain was found to be significantly low in the injectable steroid group than that of oral NSAIDs group (P<0.001).

NSAIDs mainly act by inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis, but they do not suppress the production of other inflammatory mediators like leukotrienes, cytokines, platelet activating factor etc. Steroids interfere at several steps in the inflammatory response, but the most important overall mechanism appears to be limitation of recruitment of inflammatory cells at the local site. So their actions are both direct and local.

Long-term use of oral NSAIDs can cause serious systemic side effects like gastritis, peptic ulcer, esophagitis, gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, interstitial nephritis, Na+ and water retention, thrombocytopenia, bleeding, pruritus, central nervous system, and hepatic complications.[8] As steroid is injected locally in the treatment of plantar fasciitis, chances of systemic side effects are very rare. But the potential risks for local steroid injection for plantar fasciitis include local site erythema, plantar fascia rupture, and fat pad atrophy.[9,10] In our study, the overall incidence of adverse side effects were more frequent with oral NSAIDs than local injection of steroid, but two patients presented with plantar fascia rupture later and were treated accordingly. These complications are uncommon and preventable and rupture may occur without steroid injections.[10]

CONCLUSION

On the basis of this study, it can be concluded that in comparison to oral NSAIDs, local steroid injection is a better treatment modality as it causes early, rapid and sustained relief of pain and inflammation in plantar fasciitis and is associated with lower recurrence of heel pain and lesser complications.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Simon J. Bartold.The plantar fascia as a source of pain-biomechanics, presentation and treatment. J Body Work Mov Thera. 2004;8:214–26. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gill LH. Plantar fasciitis: Diagnosis and conservative management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2004;350:2159–66. doi: 10.5435/00124635-199703000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crawford F, Atkins D, Young P, Edwards J. Steroid injection for heel pain: Evidence of short-term effectiveness. A randomized controlled trial. Rheumatology (Oxford) 1999;38:974–7. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/38.10.974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gudeman SD, Eisele SA, Heidt RS, Jr, Colosimo AJ, Stroupe AL. Treatment of plantar fasciitis by iontophoresis of 0.4% dexamethasone. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25:312–6. doi: 10.1177/036354659702500307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cardone DA, Tallia AF. Joint and Soft tissue injection. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66:283–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kane D, Greaney T, Bresnihan B, Gibney R, FitzGerald O. Ultrasound guided injection of recalcitrant plantar fasciitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1998;57:383–4. doi: 10.1136/ard.57.6.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsai WC, Wang CL, Tang FT, Hsu TC, Hsu KH, Wong MK. Treatment of proximal plantar fasciitis with ultrasound-guided steroid injection. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81:1416–21. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2000.9175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donley BG, Moore T, Sferra J, Gozdanovic J, Smith R. The efficacy of oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication in the treatment of plantar fasciitis.A randomized, prespective, placebo-controlled study. Foot Ankle Int. 2007;28:20–3. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2007.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tatli YZ, Kapasi S. The real risks of steroid injection for plantar fasciitis, with a review of conservative therapies. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2009;2:3–9. doi: 10.1007/s12178-008-9036-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Acevedo JI, Beskin JL. Complications of plantar fascia rupture associated with corticosteroid injection. Foot Ankle Int. 1998;19:91–7. doi: 10.1177/107110079801900207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]