Abstract

Purpose:

our study compared the effect of fentanyl alone with fentanyl plus intravenous Paracetamol for analgesic efficacy, opioid sparing effects, and opioid-related side effects after laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Materials and Methods:

eighty patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy were randomized into two groups, who were given either an IV placebo or an IV injection of 1g paracetamol just before induction. Both groups received fentanyl during induction and IM diclofenac for pain relief every 8 hourly for 24 h after surgery. The postoperative pain relief was evaluated by a visual analog scale (VAS) and consumption of fentanyl as rescue analgesic in the postoperative period for 24 h after surgery was measured. The incidence of PONV and sedation scores was also measured in the postoperative period.

Results:

the mean VAS score in first and second hour after surgery was less in the group receiving IV Paracetamol (3.3±0.4* vs. 5.2±0.9; 3.1±0.4* vs. 4.3±0.3); the fentanyl consumption over first 24 h was also less in the group receiving IV paracetamol (50±14.9 vs. 150±25.8). The time requirement of first dose of rescue analgesic in the postoperative period was also significantly prolonged in the group receiving IV paracetamol (76±24.7 vs. 48±15.8). There was no difference in the sedation scores and in the incidence of PONV in the two groups.

Conclusion:

The study demonstrates the usefulness of intravenous paracetamol as pre-emptive analgesic in the treatment of postoperative pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Keywords: Intravenous paracetamol, pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy, postoperative analgesia

INTRODUCTION

Pain is the most common complaint after laparoscopic cholecystectomy.[1,2] resulting in the use of rescue opioid analgesics in up to 80% patients.[3] Furthermore the pattern of pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy is complex and unlikely to benefit always from identical analgesic treatment.[4]

Paracetamol (acetaminophen; N-acetyl-p-aminophenol) is an acetanilide derivative, safe, well-tolerated drug with proven efficacy as analgesic. Its clinical effects arise most likely from central action and intravenous administration provides rapid and predictable therapeutic plasma concentration. Paracetamol was introduced for intravenous administration in a unit-dose form, ready for infusion solution in 2002 (Perfalgan®; 1 g/100 mL). It has been available in India since the past one year.

The valuable analgesic properties of opioids viz. fentanyl in the treatment of acute, intense post-operative pain are well recognized.[5] It has been found that routine treatment of opioids at the beginning of operation conferred significantly better pain control than opioids given at the end of surgery.[6] However, to reduce the opioid-related side effects and hasten recovery, drugs such as NSAIDs, paracetamol, COX-2 inhibitors, local anesthetics, steroids etc. are often used for their opioid-sparing action.[7,8]

The aim of this randomized study was to compare the analgesic efficacy of intravenous fentanyl alone versus intravenous fentanyl plus paracetamol for postoperative pain relief after laparoscopic cholecystectomy

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was approved by our ethics committee. Written and informed consent was obtained from all. Patients aged 18–70 year scheduled for laparoscopic cholecystectomy, and classified as ASA physical status I or II were included. Patients with diagnostic laparoscopy, those having contraindications to paracetamol (allergy, liver disease) or to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (esophagogastroduodenal disease, renal insufficiency, and abnormal coagulation) were excluded, as were those on treatment by steroids, NSAIDs, or opioids before surgery.

Patients received oral premedication, 5 mg Diazepam on the night before surgery.

The patients were randomly divided into two groups with 40 patients in each. The study design was randomized and unblinded. Patients were randomly allocated according to a randomization list.

In the operating room, all standard monitoring techniques were used and crystalloid infusion was started. Patients in the fentanyl group (Group F) received 100 mL of normal saline and those in the fentanyl plus paracetamol group (Group P) received 100 mL of Paracetamol IV (Perfalgan 1 gm) just before induction.

All drugs were available in the hospital pharmacy. They were administered to the patients by qualified resident doctors who were not involved in the study.

After the administration of oxygen, anesthesia was induced in both the groups with IV propofol (2 mg/kg), fentanyl (2 μg/ kg), and rocuronium (0.6 mg/kg). Anesthesia was maintained by 1–2% isoflurane in nitrous oxide and oxygen (ratio 2:1). The lungs were mechanically ventilated, and ventilation was adjusted to maintain end-expiratory CO2 between 34–36 mm Hg depending on the different stages of laparoscopy. Fentanyl was repeated in the dose of 1 μg/kg intraoperatively if both HR and NIBP increased >20% from baseline despite maintaining adequate depth of anesthesia.

After tracheal extubation, patients were transferred to the PACU. Postoperative pain was assessed using a visual analog scale (VAS; 0_ “no pain” and 10_ “worst pain imaginable”). Postoperative analgesia was provided routinely to all patients by intramuscular diclofenac at 8 h interval and intravenous fentanyl 1 μg/kg was administered as rescue analgesic when the VAS score exceeded 3.

The degree of sedation was determined according to a sedation score ranging from 0 to 2 (0_ alert, 1_ drowsy but rousable to voice, and 2_ very drowsy, but rousable to shaking). The VAS scores and sedation scores were assessed at 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 24 h after surgery. Total and incremental fentanyl consumption at these times for both the groups was also recorded. If nausea and/or vomiting occurred, the same was noted and 8 mg of ondansetron was given intravenously. The number of patients receiving antiemetics and their total dosages were noted. Patients were observed for the occurrence of any adverse effects during the first 24 h. After 24 h, patients were assessed for: (a) ability to mobilize and dress, (b) need for any analgesic, and (c) surgical complication, if any. When the patient scored yes on the former and no on the two latter questions, they were assessed ready for discharge from hospital. All measurements were recorded by the anesthesia resident who was blinded to the study drugs administered.

A sample size of 35 patients by group was calculated to detect a significant difference of 20% or more in opioid consumption with a power of 80% and a significance level of 5%. Data were reported as mean ± SD. Statistical assessment included analysis of variance (ANOVA) and student's t-test for continuous data and VAS pain data. Fisher's exact t-test and chi-square test was used to analyze nominal data; P <0.05 was considered to be significant.

RESULTS

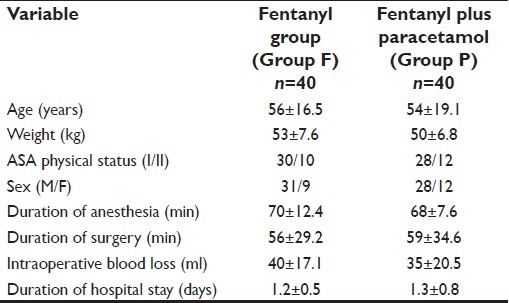

Both groups were similar in regard to age, weight, sex, ASA physical status, duration of anesthesia and surgery, intraoperative blood loss and the duration of hospital stay [Table 1]. None of the patients in either group required fentanyl intraoperatively [Table 2].

Table 1.

Patient data and characteristics (mean±SD)

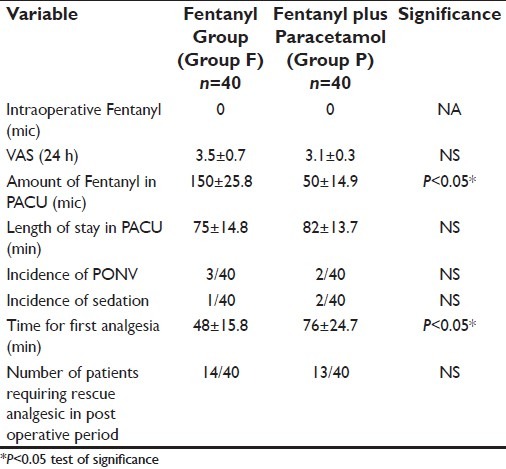

Table 2.

Post operative pain relief and side effects

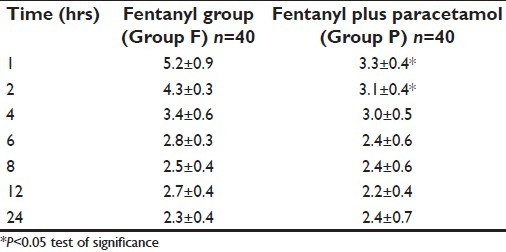

The mean VAS pain score over the 24-h period was similar in both the groups [Table 2]; however, the mean VAS score at 1 and 2 h after surgery was lower in the Group P [Table 3].

Table 3.

Pain scores (mean±SD)

The total consumption of fentanyl as rescue analgesic in PACU was significantly higher in Group F over Group P [Table 2] and the time for the first dose of rescue analgesic in the PACU was significantly lower in Group F over Group P [Table 2].

However, the number of patients requiring rescue analgesic was similar in both the groups [Table 2].

There was no difference in the length of stay in PACU, incidence of PONV and in the incidence of sedation [Table 2].

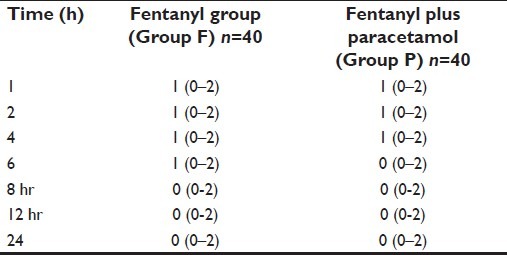

The sedation scores were similar in both the groups [Table 4]. No postoperative complications were reported from any of the groups.

Table 4.

Sedation scores

DISCUSSION

Poor pain control during the perioperative period leads to complications in both long- and short-term periods. Among these complications, atelectasis, pneumonia, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, psychological trauma etc. can be severe. With a good analgesic treatment plan, the anxiety, morbidity, cost and length of hospital stay in the postoperative period are decreased.

The overall pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy is a conglomerate of three different components: incisional pain (somatic pain), visceral pain (deep intra-abdominal pain), and shoulder pain (referred to visceral pain). Besides showing individual variation in intensity and duration, the pain is often unpredictable. It may even remain severe throughout the first week in 18% of the patients.[9]

The complex nature of pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy suggests that effective analgesic treatment should be multimodal.[9,10]

In one study,[11] where authors preoperatively administered oral oxycodone in one group (n=10) or 1000 mg oral paracetamol in another group (n=10) of female cholecystectomy patients and evaluated postoperative pain and side effects in each group, they found similar postoperative pain scores and side effects, with no difference determined between the groups.

In another study by Hein et al.[12] of 60 patients undergoing a minor gynecological surgery, 8 mg of oral lornoxicam was given to one group and 1000 mg of oral paracetamol was given to another group 60 min before induction. It was observed that VAS pain scores at postoperative 30 and 60 min were similar in both the groups; however, the VAS score was higher in the control group (did not receive medicines).

In our study, we used intravenous paracetamol 1 gm as pre-emptive analgesic in laparoscopic cholecystectomy and assessed its effects on intraoperative analgesic requirement, post-operative analgesic effectiveness, post-operative fentanyl consumption, frequency of side-effects, and hospital stay length. Our study showed that intravenous paracetamol when used as pre-emptive analgesic just before induction as part of multimodal analgesic regime has significant opioid sparing effect. This is consistent with the findings in various studies where opioid-sparing effects of NSAIDs, COX-2 inhibitors, and paracetamol have been found to be in the range of 20–30%.[13,14]

There are evidences from other surgical procedures to support clinically relevant analgesic effect of paracetamol with additives (Opioids, NSAIDs etc.) in laparoscopic cholecystectomy.[15,16] It has been reported in previous studies that propacetamol behaves favorably with different ketorolac doses producing a 31–37% decrease in the morphine requirement during the first 24 h after surgery.[17,18] Our study results are consistent all previous findings in this regard.

In our study no differences were observed between the two groups in the adequacy of analgesia as assessed by VAS scores. However, the median pain scores were significantly lower in the paracetamol group (Group P) at two intervals and the time for first analgesic requirement was significantly lower in the fentanyl alone group (Group F). This may be because of the initial loading dose of paracetamol providing a higher plasma concentration. Piguet et al.[19] had demonstrated the close correlation between plasma concentration and analgesic effect of paracetamol with intravenous doses of up to 2 gm in healthy volunteers. Juhl et al.[20] had demonstrated that the extent and duration of pain relief following third molar surgery was significantly improved after 2 g over 1 g of initial intravenous dose of paracetamol. Our results are consistent with these results.

Clinical studies have also found that 1 gm intravenous paracetamol employed alone is just as effective as 30 mg ketorolac, 75 mg diclofenac or 10 mg morphine.[21,22] Our study did not find any reduction in the opioid related side-effects (PONV, sedation etc.) in the paracetamol group (Group P) as might be expected because of the decrease in total fentanyl dose. This may be because of the lesser number of subjects in our study. Larger studies with adequate power to detect opioid-related side-effects would be able to demonstrate the reduction of dose-dependent side-effects of fentanyl, such as sedation, respiratory depression, urinary retention, or nausea.

Our study demonstrated the additive effect of combining intravenous paracetamol with fentanyl on postoperative analgesia resulting in decreased opioid amount and in slightly improved or similar pain relief. The different sites of action of these drugs in the nervous system may be the cause of better pain relief. Whereas the effect of Paracetamol is due to the inhibition of prostaglandins and activation of descending serotonergic inhibitory pathways[23,24] the analgesic effect of fentanyl is due to its agonist action in the opioid receptors of the central nervous system. The complimentary analgesic actions of the two drugs make them an important component of multimodal pain therapy.

However, our study had a few limitations. First, this was not a blind study and second, PCA pump was not used in the postoperative period. Both of these could have improved the results of our study but owing to technical reasons and limited availability it was not possible.

In conclusion, our study is the first such study conducted in Indian population. It demonstrates the usefulness of intravenous paracetamol for pre-emptive analgesia as adjunct to fentanyl for the postoperative pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Intravenous paracetamol use is associated with a satisfactory analgesia and smaller opioid consumption. This may be beneficial in the management of pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy in patients prone to opioid-related complications.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.McMohan AJ, Russel IT, Ramsay G, Sunderland G, Baxter JN, Anderson JR, et al. Laparoscopic and minilaparotomy cholecystectomy: A randomized trial comparing postoperative pain and pulmonary function. Surgery. 1994;115:533–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Troidl H, Spangenberger W, Langen R, al-Jaziri A, Eypasch E, Neugebauer E, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy: technical performance, safety and patient's benefit. Endoscopy. 1992;24:252–61. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1010477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Madsen MR, Jensen KE. Postoperative pain and nausea after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1992;2:303–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mouton WG, Bessell JR, Otten KT, Maddern GJ. Pain after laparoscopy. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:445–8. doi: 10.1007/s004649901011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Practice guidelines for acute pain management in the perioperative setting: An updated report the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Acute Pain Management. Anesthesiology. 2004;100:1573–81. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200406000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lane GE, Lathrop JC, Boysen DA, Lane RC. Effect of intramuscular intraoperative pain medication on narcotic usage after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Am Surg. 1996;62:907–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boccara G, Chaumeron A, Pouzeratte Y, Mann C. The preoperative administration of ketoprofen improves analgesia after laparoscopic cholecystectomy in comparison with propacetamol or postoperative ketoprofen. Br J Anaesth. 2005;94:347–51. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marret E, Kurdi O, Zufferey P, Bonnet F. Effects of nonsteroidal anti-iflammatory drugs on patient-controlled analgesia side-effects: Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Anesthesiology. 2005;102:1249–60. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200506000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bisgaard T, Klarskov B, Kehlet H, Rosenberg J. Characteristics and prediction of early pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Pain. 2001;90:261–9. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00406-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Michaloliakou C, Chung F, Sharma S. Preoperative multimodal analgesia facilitates recovery after ambulatory laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Anesth Analg. 1996;82:44–51. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199601000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Speranza R, Martino R, Laveneziana D, Sala B. Oxycodone versus paracetamol in oral premedication in cholecystectomy. Minerva Anestesiol. 1992;58:191–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hein A, Norlander C, Blom L, Jakobsson J. Is pain prophylaxis in minor gynaecological surgery of clinical value.A double blind placebo controlled study of Paracetamol 1 gm versus lornoxicam 8 mg given orally? Ambul Surg. 2001;9:91–4. doi: 10.1016/s0966-6532(01)00078-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fayaz MK, Abel RJ, Pugh SC, Hall JE, Djaiani G, Mecklenburgh JS. Opioid sparing effects of diclofenac and Paracetamol lead to improved outcomes after cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anaesth. 2004;18:742–7. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hernández-Palazón J, Tortosa JA, Martínez-Lage JF, Pérez-Flores D. Intravenous administration of Propacetamol reduces morphine consumption alter spinal fusion surgery. Anesth Analg. 2001;92:1473–6. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200106000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hyllested M, Jones S, Pedersen JL, Kehlet H. Comparative effect of Paracetamol, NSAIDs or their combination in post-operative pain management. Br J Anaesth. 2002;88:199–214. doi: 10.1093/bja/88.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Remy C, Marret E, Bonnet F. Effects of acetaminophen on morphine side-effects and consumption after major surgery: Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Br J Anaesth. 2005;94:505–13. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reuben SS, Connelly NR, Steinberg R. Ketorolac as an adjunct to patient-controlled morphine in postoperative spine surgery patients. Reg Anesth. 1997;22:343–6. doi: 10.1016/s1098-7339(97)80009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reuben SS, Connelly NR, Lurie S, Klatt S, Gibson CS. Dose-response of Ketorolac as an adjunct to patient-controlled analgesia morphine in patients after spinal fusion surgery. Anesth Analg. 1998;87:98–102. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199807000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piguet V, Desmeules J, Dayer P. Lack of acetaminophen ceiling effect on R-III nociceptive flexion reflex. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;53:321–4. doi: 10.1007/s002280050386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Juhl G, Norholt S, Tonnese E, Hiesse-Provost O, Jensen TS. Analgesic efficacy and safety of intravenous Paracetamol (acetaminophen) administered as a 2g starting dose following 3rd molar surgery. Eur J Pain. 2006;10:371–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flower RJ, Vane JR. Inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis in brain explains the anti-pyretic effect of Paracetamol (4-aminodophenol) Nature. 1972;240:410–1. doi: 10.1038/240410a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tjolsen A, Lund A, Hole K. Antinociceptive effect of Paracetamol in rats in partly dependent on spinal serotonergic systems. Eur J Pharmacol. 1991;193:193–201. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(91)90036-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson BJ. Paracetamol (Acetaminophen): mechanisms of action. Paediatr Anaesth. 2008;18:915–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2008.02764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Graham GG, Scott KF. Mechanism of action of paracetamol. Am J Ther. 2005;12:46–55. doi: 10.1097/00045391-200501000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]