Abstract

Background:

Nalbuphine has been used intrathecally as an adjuvant in previous studies, but none clearly state the most effective dose of nalbuphine. The purpose of our study was to establish the effectiveness of intrathecal nalbuphine as an adjuvant, compare three different doses and determine the optimum dose with prolonged analgesic effect and minimal side-effects.

Materials and Methods:

In this prospective, randomized, double-blinded, controlled study, 100 ASA I and II patients undergoing lower limb orthopedic surgery under subarachnoid block (SAB), were randomly allocated to four groups: A, B, C and D, to receive 0.5 ml normal saline (NS) or 0.2, 0.4 and 0.8 mg nalbuphine made up to 0.5 ml with NS added to 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine 12.5 mg (total volume 3 ml), respectively. The onset of sensory and motor blockade, two-segment regression time of sensory blockade, duration of motor blockade and analgesia, visual analogue scale (VAS) pain score and side-effects were compared between the groups.

Results:

Two-segment regression time of sensory blockade and duration of effective analgesia was prolonged in groups C (0.4 mg nalbuphine) and D (0.8 mg nalbuphine) (P<0.05), and the incidence of side-effects was significantly higher in group D (P<0.05) compared with the other groups.

Conclusion:

Nalbuphine used intrathecally is a useful adjuvant in SAB and, in a dose of 0.4 mg, prolongs postoperative analgesia without increased side-effects.

Keywords: Hyperbaric bupivacaine, nalbuphine, subarachnoid block

INTRODUCTION

The first report on the use of intrathecal opioids (ITO) for acute pain treatment was in 1979 by Wang and colleagues.[1] Use of ITO as adjuncts has a definite place in the present regional anesthesia practice. Various opioids have been used along with bupivacaine to prolong its effect, to improve the quality of analgesia and minimize the requirement of postoperative analgesics.[2,3] Nalbuphine is a semisynthetic opioid with mixed mu antagonist and k agonist properties.[4] Previous studies have shown that epidural or intrathecal administration of nalbuphine produces a significant analgesia accompanied by minimal pruritus and respiratory depression.[5,6] Culebras et al. in 2002 used intrathecal nalbuphine in doses 0.2, 0.8 and 1.6 mg with 10 mg of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine in patients undergoing caesarean section under subarachnoid block (SAB) and found 0.8 mg of nalbuphine as an effective dose.[7] But, they have not used 0.4 mg nalbuphine. Lin et al. found that the addition of intrathecal nalbuphine 0.4 mg to hyperbaric tetracaine, compared with intrathecal morphine 0.4 mg for SAB, improved the quality of intraoperative and postoperative analgesia, with fewer side-effects.[5] In this prospective, double-blind, randomized, controlled study, we tried to establish the effectiveness of intrathecal nalbuphine as an additive by comparing with the control and determining the optimal dose of intrathecal nalbuphine using 0.2, 0.4 and 0.8 mg added to 12.5 mg hyperbaric bupivacaine 0.5% (total volume 3 ml) to have prolonged pain relief with minimal side-effects in patients undergoing lower limb orthopedic surgical procedures under SAB.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was approved by the local institutional ethics committee and written informed consent was obtained from all patients before participation. One hundred patients, ASA physical status I and II, aged 20–60 years, scheduled for elective lower limb orthopedic surgeries, of duration less than 3 h, under SAB, were included in the study. Patients were randomly allocated to one of four groups (n=25). They received either normal saline (NS) 0.5 ml (group A), nalbuphine 0.2 mg (group B), nalbuphine 0.4 mg (group C) or nalbuphine 0.8 mg (group D), made up to 0.5 ml volume with NS, mixed with 12.5 mg of hyperbaric bupivacaine 0.5% (total volume 3 ml). The baricity of the study drugs was comparable. The drugs were prepared by one of the authors who did not take further part in the study. An experienced anesthesiologist who did not participate in the study performed the SAB and was blinded to the study drug used. Both patients and observers, who recorded and analyzed the data, were blinded to the study drug received.

Patients with a history of adverse response to bupivacaine or nalbuphine, pregnant patients, patients receiving phenothiazine, other tranquilizers, hypnotics or other central nervous system depressants (including alcohol) or suffering from peripheral or central neurological, cardiac, respiratory, hepatic, renal disease or with body weight more than 100 kg or less than 40 kg and height less than 145 cm or more than 160 cm and patients having contraindication to SAB were excluded from study.

All the patients fasted for at least 6 h before the procedure. After securing intravenous (18G) access in dorsum of the left hand and attaching routine monitors, preloading with Ringer's lactate solution 15 ml/kg over 10 min was done. SAB was performed with 3 ml of the study drug injected in L3/4 or L4/5 intervertebral space, using a 25 gauge Quincke spinal needle, in the sitting position, maintaining aseptic precautions, according to the standard institutional protocol. Thereafter, patients were placed in the supine or lateral position for surgery. Intraoperative fluid replacements were given as necessary depending on the blood loss and hemodynamic parameters. Intraoperative hypotension and bradycardia was managed with colloids and atropine 0.6 mg, respectively. In case of any respiratory depression, oxygen through facemask at 6 l was administered. Advanced equipments and drugs for resuscitation, airway management and ventilation were kept ready.

The onset of sensory blockade (time taken from the end of injection to loss of pin prick sensation at T10 dermatome) and complete motor blockade (time taken from the end of injection to development of grade IV motor block, modified Bromage's criteria[8]), highest level of sensory blockade, duration of sensory blockade (two-segment regression time from highest level of sensory blockade), duration of motor blockade (time required for motor blockade return to Bromage's grade I from the time of onset of motor blockade) and duration of effective analgesia (time from the intrathecal injection to the first analgesic requirement, visual analogue scale [VAS] score 3.5 or more) were recorded.

The changes in pulse rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, oxygen saturation (SpO2) and respiratory rate were recorded at 0, 2, 5,10 and 15 min and then at 15-min intervals up to 300 min after SAB, or up to the end point of study. Any side-effects in the form of post-operative hypotension, bradycardia, respiratory depression (judged by respiratory rate less than 10 or SpO2 <90%) nausea and vomiting (in presence of stable hemodynamic parameters) and pruritus were recorded. Those patients who did not develop sensory block up to T10 and Grade IV motor block were excluded from the study.

Intensity of pain was assessed by VAS[9] at 0, 10, 15, 30 and 60 min and then at 30-min intervals till 300 min after injection or until the patient received a rescue analgesic. Patients reporting a VAS score 3.5 or more received rescue analgesics in the form of injection (Inj) Diclofenac 75 mg IM. Incidence of nausea, vomiting and pruritus was noted. Nausea and vomiting was treated with Inj Ondansetron 4 mg i.v. and pruritus with anti-histaminics. Data were analyzed using Student's t-test (paired and unpaired), one-way ANOVA and Fisher's test with the help of Epical C2000 software. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

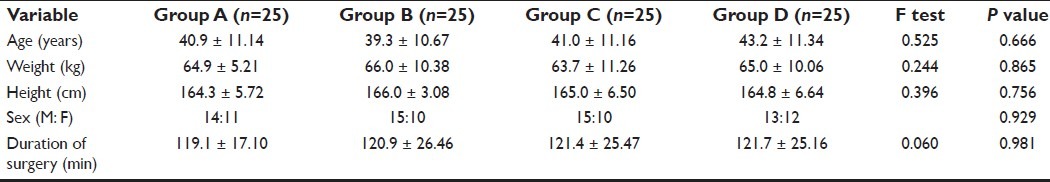

All the demographic variables like age, weight, height, sex ratio and duration of surgery were comparable in all the four groups; P>0.05 [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic data and duration of surgery in groups A, B, C and D (mean ± SD)

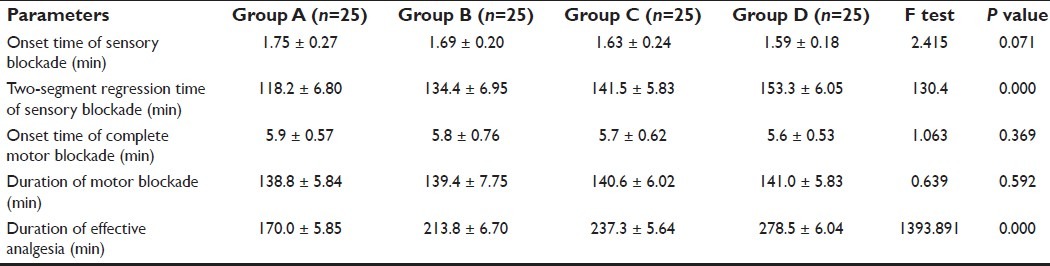

The onset time of sensory and motor blockade were found to be statistically insignificant (P>0.05) among all the four groups [Table 2]. There was no case of failure or inadequate blockade after SAB. Maximum sensory level achieved by all groups was T6, and a T10 level was achieved by all patients. Two-segment regression time of sensory blockade was prolonged progressively in groups A, B, C and D [Table 2]. The duration of analgesia was progressively prolonged in groups B, C and D as compared with group A; P<0.05 [Table 2]. Group D recorded the longest duration of analgesia with a mean of 278.5 min compared with 237.3 min in group C [Table 2]. Duration of motor blockade was comparable in all the four groups; P=0.592 [Table 2].

Table 2.

Sensory block, motor block and analgesia in groups A, B, C and D (mean ± SD)

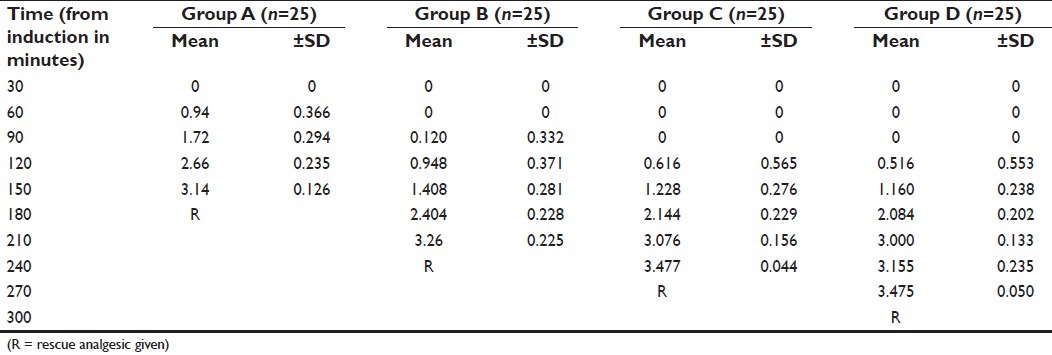

The patients recorded a mean VAS score of 3.475 at 270 min (group D), 3.477 at 240 min (group C), 3.26 at 210 min (group B) and 3.14 at 150 min after starting of anesthesia and were given rescue analgesics when VAS was 3.5 or more [Table 3].

Table 3.

Comparison of VAS scores (mean ± SD) among groups A, B, C and D

On intragroup comparison after SAB, there was no statistically significant difference in the intraoperative mean pulse rate, systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure, respiratory rate and SpO2 between the groups (Table not provided).

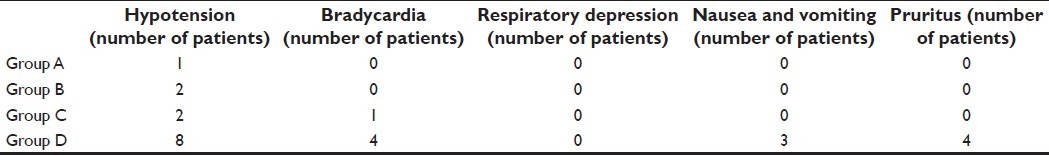

The side-effects, postoperative hypotension (P=0.010), bradycardia (P=0.004), nausea and vomiting with stable hemodynamic parameters (P=0.023) and pruritus (P=0.004), were significantly higher in group D. We did not come across any case of respiratory depression in any of the groups [Table 4].

Table 4.

Side-effects in the groups A, B, C and D (n=25) in the postoperative period

DISCUSSION

ITO used as adjuncts are capable of producing analgesia of prolonged duration but allow early ambulation of patients because of their sympathetic and motor nerve-sparing activities.[10,11] The popularity of ITO was undermined by reports of side-effects, such as respiratory depression, pruritus and postoperative nausea and vomiting.[12] Nalbuphine is an opioid (393Da) structurally related to oxy-morphone. It is a highly lipid-soluble opioid with an agonist action at the k opioid receptor and an antagonist activity at the mu opioid receptor.[13,14] Nalbuphine and other k agonists had provided reasonably potent analgesia in certain models of visceral nociception.[4] They have a short duration of action, consistent with their lipid solubility and rapid clearance compared with other opioids like morphine. Recent reports suggest that the safety of ITO are more assured than previously published studies.[15] Nalbuphine given systemically has a reduced incidence of respiratory depression and has been used to antagonize the side-effects of spinal opiates.[16–18] There are a few studies of neuraxial administration of nalbuphine that have shown to produce a significant analgesia accompanied by minimal pruritus and respiratory depression.[6]

Yoon et al. studied 60 obstetric patients scheduled for caesarean section under SAB to receive morphine 0.1 mg or nalbuphine 1 mg or morphine 0.1 mg with nalbuphine 1 mg in addition to 0.5% bupivacaine 10 mg and concluded that effective analgesia was prolonged in the morphine group and morphine with nalbuphine group, but the incidence of pruritus was significantly lower in the nalbuphine group, while the incidence of nausea and vomiting did not differ in the different groups.[19]

Fournier et al. studied the analgesic effects of intrathecal morphine 160 mcg and nalbuphine 400 mcg in geriatric patients scheduled for elective total hip replacement under continuous spinal anesthesia, given in the postoperative period, in the recovery room, and concluded that administration of intrathecal nalbuphine resulted in a significantly faster onset of pain relief and shorter duration of analgesia than intrathecal morphine.[6]

Lin et al. evaluated the analgesic effect of subarachnoid administration of tetracaine combined with 0.4 mg morphine or 0.4 mg nalbuphine for spinal anesthesia in 60 ASA physical status class I or II patients. No differences in complete or effective analgesia were found between the groups. They found that the addition of 0.4 mg nalbuphine or morphine improves the quality of intraoperative analgesia that can last into the postoperative period, but the side-effects were lesser in the nalbuphine group than in the morphine group.[5]

The only study comparing the different doses of nalbuphine was by Culebras et al., who studied intrathecal nalbuphine in doses of 0.2, 0.8 and 1.6 mg in 90 obstetric patients undergoing caesarean section and found 0.8 mg as the most effective dosage.[7]

We had consciously excluded the 1.6 mg group in our study as they reported that 1.6 mg nalbuphine did not improve analgesia compared with the 0.8 mg group, exhibiting a ceiling effect, and was associated with higher side-effects. We formulated our study to determine whether nalbuphine prolongs analgesia by comparing with control and to find out the optimum dose of intrathecal nalbuphine by comparing the 0.2, 0.4 and 0.8 mg doses, which will provide prolonged postoperative analgesia without increased side-effects. We are not aware of any previous single study that has compared these three doses. In our study, we found that the duration of effective analgesia progressively increased in groups B, C and D compared with the control group A, proving the effectiveness of intrathecal nalbuphine as adjuvant to 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine in SAB [Tables 2 and 3]. Our study results are in accordance with previous studies.[5,6]

The 0.4 mg group C had comparable postoperative analgesia but significantly lower side-effects (P<0.05) compared with the 0.8 mg group D, while the 0.2 mg group B had significantly lesser duration of effective analgesia compared with groups C and D (P<0.05). The 0.8 mg group has the advantage of longest duration of analgesia [Tables 2 and 3, but at the cost of statistically significant side-effects (P<0.05) [Table 4]. Our results differ from the study by Culebras et al., as they have not studied the 0.4 mg group, and our study was conducted with a different demographic patient population, in different surgery and with 12.5 mg 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine compared with 10 mg 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine in their study.

There are safety issues regarding the intrathecal use of nalbuphine and insufficient data to guarantee safe intrathecal use in human patients. There was an animal study by Rawal et al. that examined the effects of nalbuphine in a dose of 0.75 mg/kg and reported no behavioral or systematic histo-pathologic abnormalities.[20] Neuraxial use of nalbuphine is in modern anesthesia practice for more than 10 years. We are not aware of any reports of neurotoxicity of intrathecal nalbuphine since then. Some of the previous studies were even conducted with intrathecal nalbuphine in pregnant patients, but no neurotoxicity was reported in them.[7,18] The FDA in 2005 advised that nalbuphine may be used during labor and delivery only if clearly indicated and if the potential benefit outweighs the risk. We are unaware of any definite caution in the use of nalbuphine by any statutory authority in nonpregnant patients and in subjects more than 18 years old. We have excluded pregnant patients from our study and obtained clearance from the local institutional ethical committee.

CONCLUSION

Intrathecal nalbuphine prolongs the duration of postoperative analgesia when used as an adjunct, and 0.4 mg is the most effective dose that prolongs early postoperative analgesia without increasing the risk of side-effects. We recommend 0.4 mg as the optimal dose of nalbuphine if used intrathecally along with 12.5 mg 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine for SAB in patients undergoing lower limb orthopedic surgeries.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wang JK, Nauss LA, Thomas JE. Pain relief by Intrathecally applied morphine in man. Anesthesiology. 1979;50:149–51. doi: 10.1097/00000542-197902000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Veering B. Focus on Adjuvants in regional Anesthesia. Euro Anesthesia. 2005;28-31:217–21. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morgan M. The rational use of intrathecal and extradural opioids. Br J Anaesth. 1989;63:165–88. doi: 10.1093/bja/63.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmauss C, Doherty C, Yaksh TL. The analgesic effects of an intrathecally administered partial opiate agonist, nalbuphine hydrochloride. Eur J Pharmacol. 1982;86:1–7. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(82)90389-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin ML. The analgesic effect of subarachnoid administration of tetracaine combined with low dose of morphine or nalbuphine for spinal anaesthesia. Ma Zui Xue Za Zhi. 1992;30:101–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fournier R, Gamulin Z, Macksay M, Van Gessel E. Intrathecal morphine versus nalbuphine for post operative pain relief after total hip replacement. Anesthesiology. 1998;89:867. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2000.440808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Culebras X, Gaggero G, Zatloukal J, Kern C, Marti RA. Advantages of Intrathecal nalbuphine, compared with intrathecal morphine, after Cesarean delivery: An evaluation of postoperative analgesia and adverse effects. Anesth Analg. 2000;91:601–5. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200009000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bromage PR. Epidural analgesia. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crichton N. Information point: Visual analogue scale (VAS) J Clin Nursing. 2001;10:697–706. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tawfik MO. Mode of action of intraspinal opioids. Pain Rev. 1994;1:275–94. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Terajima K, Onodera H, Kobayashi M, Yamanaka H, Ohno T, Konuma S, et al. Efficacy of intrathecal morphine for analgesia following elective cesarean section: Comparison with previous delivery. J Nippon Med Sch. 2003;70:327–33. doi: 10.1272/jnms.70.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chaney MA. Side effects of intrathecal and epidural opioids. Can J Anesth. 1995;42:891–903. doi: 10.1007/BF03011037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zarr GD, Werling LL, Brown SR, Cox BM. Opioid ligand binding sites in the spinal cord of the guinea-pig. Neuropharmacology. 1986;25:47–80. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(86)90170-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Souza EB, Schmidt WK, Kuhar MJ. Nalbuphine: An autoradiographic opioid receptor binding profile in the central nervous system of an agonist/antagonist analgesic. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1988;244:391–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ready LB, Loper KA, Nessly M, Wild L. Postoperative epidural morphine is safe on surgical wards. Anesthesiology. 1991;75:452–6. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199109000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henderson SK, Cohen H. Nalbuphine augmentation of analgesia and reversal of side effects following epidural hydromorphone. Anesthesiology. 1986;65:216–8. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198608000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Penning JP, Samson B, Baxter AD. Reversal of epidural morphine-induced respiratory depression and pruritus with nalbuphine. Can J Anaesth. 1988;35:599–604. doi: 10.1007/BF03020347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang T, Breen TW, Archer D, Fick G. Comparison of 0.25 mg and 0.1 mg intrathecal morphine for analgesia after cesarean section. Can J Anaesth. 1999;46:627–60. doi: 10.1007/BF03012975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoon JY, Jee YS, Hong JY. A Comparison of Analgesic Effects and side effects of intrathecal morphine, nalbuphine and morphine-nalbuphine mixture for pain relief during a caesarean section. Korean J Anaesthesiol. 2002;42:627–33. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rawal N, Nuutinen L, Raj PP, Lovering SL, Gobuty AH, Hargardine J, et al. Behavioral and histopathologic effects following intrathecal administration of butorphanol, sufentanil, and nalbuphine in sheep. Anesthesiology. 1991;75:1025–34. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199112000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]