Abstract

Background:

Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) is a serious concern in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC), with an incidence of 46 to 72%. The purpose of this study was to compare the antiemetic efficacy of intravenous (iv) ondansetron 8 mg, ramosetron 0.3 mg, and palonosetron 0.075 mg for prophylaxis of PONV in high-risk patients undergoing LC.

Materials and Methods:

In this prospective, randomized, double-blinded study, 87 female patients, 18 to 70 years of age (ASA I and II) and undergoing elective LC under general anesthesia were randomly allocated into three equal groups, the ondansetron group (8 mg iv; n=29), the ramosetron group (0.3 mg iv; n=29), and the palonosetron group (0.075 mg iv; n=29), and the treatments were given just after completion of surgery before extubation. The incidence of complete response (patients who had no PONV and needed no other rescue antiemetic medication), nausea, vomiting, retching, and need for rescue antiemetics over 24 hours after surgery were evaluated.

Results:

The number of complete responders were 19 (65.5%) for ramosetron, 11 (37.9%) for palonosetron, and 10 (34.5%) for ondansetron, representing a significant difference overall (P=0.034) as well as between ramosetron and ondansetron (P=0.035). Comparison between ramosetron and palonosetron also showed a clear trend favoring the former (P=0.065).

Conclusion:

Ramosetron 0.3 mg iv was more effective than palonosetron 0.075 mg and ondansetron 8 mg in the early postoperative period, but there was no significant difference in the overall incidence of nausea suffered.

Keywords: Laparoscopic cholecystectomy, ondansetron, palonosetron, postoperative nausea and vomiting, ramosetron

INTRODUCTION

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) has rapidly emerged as an alternative to open cholecystectomy and is a routinely performed procedure for symptomatic cholelithiasis.[1] But, postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) is a distressing and frequent adverse events of anesthesia and surgery, and the incidence following LC is as high as 46 to 72%.[2,3] 5-HT3 receptor antagonists (5HT3RA) belong to the Cys-loop superfamily of ligand-gated ion channels and are first-line therapies in the prevention of PONV.[4,5] 5HT3RA have an enviable safety profile, with minor side-effects and rare cardiac conduction abnormalities. Ondansetron was the first 5HT3RA with a relatively short half-life of 3 to 5 hours and may be given several times a day depending on the severity of the symptoms. Ramosetron is a recently developed 5HT3RA that exhibits significantly greater binding affinity for 5-HT3 receptors and a slower dissociation rate from receptor binding, resulting in more potent and longer receptor antagonizing, which may last up to 48 hours.[6] Palonosetron is the first of “second-generation” 5HT3RA and is superior to the “first generation” 5HT3RAs in respect of high receptor-binding affinity and it may also bind to the receptor at an allosteric site. It has a prolonged mean elimination half-life of about 40 hours.[7] 5HT3RA undergo Phase I metabolism in the liver by the cytochrome P450 enzyme system; ondansetron, ramosetron, and palonosetron are primarily metabolized by CYP3A4, CYP1A2, and CYP2D6, respectively.[8]

This study was conducted to determine the efficacy of three 5HT3RA—ondansetron, ramosetron, and palonosetron—in the prevention of PONV for patients undergoing LC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

For this study, 87 female patients scheduled to undergo LC were randomized in a double-blind manner to receive ondansetron 8 mg (group O, n=29), ramosetron 0.3 mg (group R, n=29), and palonosetron 0.075 mg (group P, n=29) intravenously just after completion of surgery before extubation. The study was commenced after obtaining approval from the institutional ethical committee and written informed consent from patients. Our patients were American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) I and II. We have deliberately excluded ASA III and IV patients as uremic patients, patients with cardiovascular disease with hypotension, neurological disease, advanced liver disease and gastro-intestinal disease have a definite association with nausea and vomiting irrespective of surgical and anesthetic technique. Patients who have received antiemetic drug within the preceding 24 hours, those with a history of alcohol or drug abuse within last 3 months, those who were allergic to any of the study medications, and those with a body weight more than 30% of the ideal body weight were also excluded as these may either alter or hamper our study results.

A standardized anesthesia regimen was followed. All patients received midazolam 1 mg intravenous (iv), glycopyrrolate 0.2 mg iv, and butorphanol 1 mg iv for premedication 10 minutes before surgery. Butorphanol's onset of analgesia is within a few minutes for iv administration, with peak analgesic activity occurring within 30 to 60 minutes, and the duration of analgesia is generally 3 to 4 hours. In our institution, the duration of LC was approximately 1 hour and so no other opioids were required intraoperatively.

General anesthesia was induced with thiopentone sodium 3 to 5 mg/kg and tracheal intubation was facilitated with suxamethonium 1.5 mg/kg. Propofol itself has an antiemetic property, and we consciously avoided its use in this study. Thiopentone also gives better hemodynamic stability than propofol, and is helpful regarding hypotensive PONV. Anesthesia was maintained with sevoflurane (0.5–1%), nitrous oxide (60%), and atracurium (0.5 mg/kg). We are using the closed system to deliver anesthetic gases and are using nitrous as the carrier gas. 1 MAC is necessary for maintenance of anesthesia, and 1 MAC of sevoflurane is between 1.71 and 2.05%, which is reduced to 0.66% by the addition of 60% nitrous oxide.[9] At the end of surgery, residual neuromuscular block was reversed with neostigmine (0.05 mg/kg) and glycopyrrolate (0.005 mg/kg) in all patients. The study medication (ondansetron, ramosetron, or palonosetron) was administered intravenously just at the end of surgery before extubation. For postoperative pain control, diclofenac 75 mg im was administered 30 minutes before the end of surgery and repeated 8-hourly for postoperative analgesia.[10] We had provision of postoperative rescue analgesic in the form of repeat dose of injection butorphanol 2 mg im, but none of our patients required it. Patients were observed in the postanesthesia care unit before being transferred to the ward.

The incidence of complete response, vomiting, and intensity of nausea using a 100-mm visual analogue scale (0, none; 100, maximum), retching, and need for rescue antiemetics was evaluated for 24 hours, divided into three intervals: 0–2 hours, 2–6 hours, and 6–24 hours.

Complete response was defined as no PONV and no need for another rescue antiemetic medication.

Vomiting was defined as the forceful expulsion of gastric contents from the mouth.

Nausea was defined as the subjectively unpleasant sensation associated with awareness of the urge to vomit.

Retching was defined as the labored, spastic, rhythmic contraction of the respiratory muscles without the expulsion of gastric contents.

Patients were asked to communicate their degree of nausea during the interval of assessment. Rescue antiemetics, injection ondansetron 4 mg iv, were provided on ranging of nausea intensity from moderate to severe (VAS score >50), patients request, and on vomiting. The hemodynamic data were noted both during the intraoperative and postoperative periods at regular intervals. Adverse events were evaluated and recorded by the investigator during the 24-hour observation period. In our institution, the surgeons did not usually ask for intraoperative nasogastric tube insertion. Only two of the 87 patients studied required nasogastric tube insertion. But, routine use of nasogastric tube does not affect the incidence of PONV.[11]

For the purpose of sample size calculation, the number of complete responders was taken as the primary outcome measure. It was estimated that 24 subjects would be required per group in order to detect 40% improvement in complete responder rate for the better-performing drug, assuming that a minimum of one-third of the subjects would be complete responders, whatever the drug. We therefore set our recruitment target at 30 subjects per group to account for a possible 20% dropout rate.

Numerical data have been summarized by mean and standard deviation. Median and interquartile values have also been presented for nausea visual analogue score (VAS) scores as this variable was nonparametric. Numerical variables have been compared between groups by one-way analysis of variance when normally distributed and by the Kruskal-Wallis test if otherwise. Categorical variables have been summarized as percentages and compared between groups by the Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. All analyses have been two-tailed and P<0.05 has been considered statistically significant. Analysis was performed by Statistica version 6 (StatSoft Inc., 2001; Tulsa, OK USA) software.

RESULTS

We recruited 29 subjects per group, and all of them completed the scheduled evaluation.

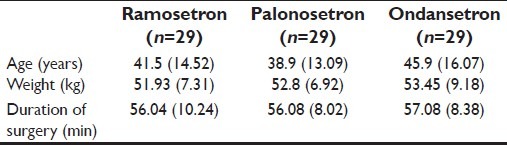

The groups were comparable with respect to age, weight, and duration of surgery, but the data showed no statistical significance, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient's characteristics and duration of surgery

The hemodynamic data were noted both during the intraoperative and postoperative periods at regular intervals. There was no statistically significant difference in the measurements of vitals of the three groups.

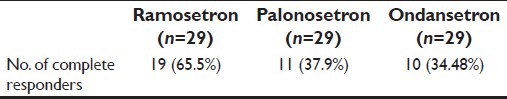

The number of complete responders was 19 (65.5%) for ramosetron, 11 (37.9%) for palonosetron, and 10 (34.48%) for ondansetron, representing a significant difference overall (P=0.034) as well as between ramosetron and ondansetron (P=0.035). Comparison between ramosetron and palonosetron also showed a trend favoring the former (P=0.065). Palonosetron and ondansetron were comparable [Table 2].

Table 2.

Number of complete responders

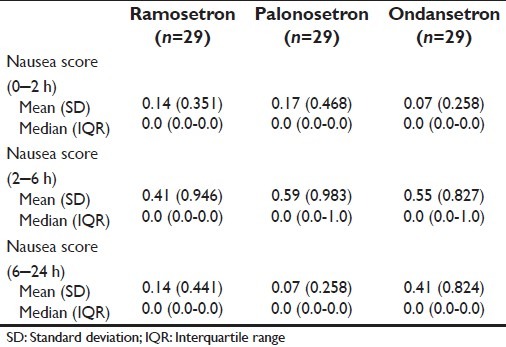

The evolution of nausea intensity, as rated by VAS scoring, has been depicted in Table 3.

Table 3.

Change in nausea score over time in the three study groups

There was no significant difference in nausea between groups in any of the three time intervals.

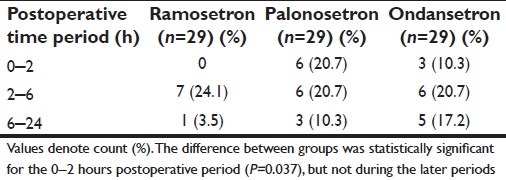

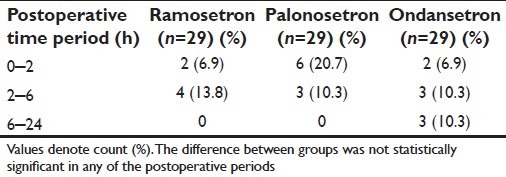

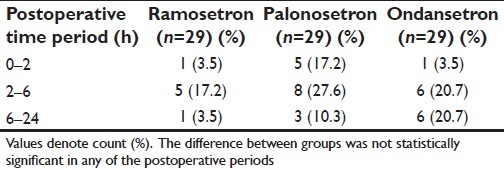

The number of subjects in each of the three study groups experiencing at least one vomiting episode within the relevant time intervals is summarized in Table 4. This Table shows that a significantly greater number of subjects suffered vomiting in the early (0–2 hours) postoperative period if they were in the palonosetron or ondansetron groups compared with the ramosetron group, which actually had no vomiting during this period. However, this difference between groups were no longer found in the later periods, when small and comparable numbers in all three groups experienced vomiting. So far, as retching was concerned, small and comparable numbers experienced such episodes in the different postoperative periods, which are shown in Table 5. Table 6 depicts the requirement of rescue antiemetic medication for subjects experiencing more than trivial nausea-vomiting. These numbers were also comparable between the ramosetron, palonosetron, and ondansetron groups.

Table 4.

Frequency of vomiting in the study groups

Table 5.

Frequency of retching in the study groups

Table 6.

Number of subjects requiring rescue antiemetics in the study groups

Summary for retching episodes is presented in Table 5.

DISCUSSION

PONV remains a significant problem in modern anesthetic practice, and has adverse consequences such as delayed recovery, unexpected hospital admission, delayed return to work of ambulatory patients, pulmonary aspiration, wound dehiscence, and dehydration.[12] Therefore, prevention of PONV in surgical patients gets similar priority to that of alleviating postoperative pain.[13]

The vomiting center is an indiscrete area located in the lateral reticular formation of the medulla, which is responsible for controlling and coordinating nausea and vomiting. The center receives a wide range of afferent inputs from receptors in the gastrointestinal tract, peripheral pain receptors, the nucleus solitarius, vestibular system, the cerebral cortex, and the chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ). The exact mechanism of PONV caused by pneumoperitoneum is not known. Pneumoperitoneum probably stimulates the mechanoreceptors in the gut, and this increases the risk of PONV. Pneumoperitoneum-induced intestinal ischemia may release serotonin and other neurotransmitters, which could lead to PONV. But Kim et al. found that lowering the pneumoperitoneum pressure to 8 mmHg does not reduce the incidence of PONV.[14]

Acetylcholine and histamine are two important neurotransmitters of the vomiting center and dopamine and 5-hydroxytryptamine are two important neurotransmitters located in the CTZ. The 5HT3RA act on the 5-HT3 receptor, a subtype of serotonin receptor found in terminals of the vagus nerve and in certain areas of the brain.

Although ondansetron 4 or 8 mg has been recommended for preventing PONV, the meta-analysis by Tramer et al. suggested that an 8 mg dose of ondansetron was optimal for the prevention of PONV.[15] A study by Ryu et al. also suggests that ondansetron 8 mg is more effective than 4 mg.[16] Therefore, we selected ondansetron 8 mg for this study.

According to Fujii et al., ramosetron is effective in preventing PONV after gynecological surgery, and ramosetron 0.3 mg is an effective dose for preventing PONV. In addition, the manufacturer's recommended dose is 0.3 mg iv once a day.[17,18] Therefore, ramosetron at the 0.3 mg dose was chosen for our study.

Based on the studies of Candiotti et al., the minimum effective dose of palonosetron in the prophylaxis of PONV is 0.075 mg, and this has been approved by the food drug agency (FDA). They used palonosetron 0.025 mg, 0.05 mg, and 0.075 mg groups, and the incidence of early emesis was lower in the palonosetron 0.075 mg group compared with placebo.[5] In our study, we have decided to use palonosetron 0.075 mg.

We are unaware of any study where ondansetron, ramosetron, and palonosetron have been compared together for their respective efficacy.

Previous studies conducted using ramosetron had favorable outcomes. Feng et al. reported that ramosetron was more effective than granisetron in preventing emesis, nausea, and anorexia in the time period of 18 to 24 hours after chemotherapy.[19] Takenaka et al. concluded that ramosetron had been the most effective in comparison with granisetron and ondansetron in reducing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting.[20] Fuji et al. showed that the complete response during the first 24 hours after anesthesia was 85% with granisetron and 93% with ramosetron.[21] Kim et al. showed that ramosetron 0.3 mg was as effective as ondansetron 8 mg in decreasing the incidence of PONV in female patients during the first 24 hours after gynecological surgery.[22] In another study, Ryu et al. reported that ramosetron 0.3 mg and ondansetron 8 mg are more effective than ondansetron 4 mg for the prevention of PONV after LC.[16]

Studies conducted with palonosetron are mainly placebo based. According to Candiotti et al., patients with Apfel score >2, undergoing day-case laparoscopy, received prophylaxis against PONV with palonosetron 0.025 mg, 0.05 mg, 0.075 mg, or placebo. Nitrous oxide was used but no other prophylactic antiemetics were administered. A dose-dependent increase in complete response was observed, with rates in the 0- to 24-hour period for the placebo, palonosetron 0.025 mg, 0.05 mg, and 0.075 mg groups of 26%, 33%, 39%, and 43%, respectively. The incidence of early emesis was lower in the palonosetron 0.075 mg group compared with placebo (33% vs 44%), as was the severity of nausea.[5] In a study by Saito et al., 1143 cancer patients who were receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy were randomly assigned to either single-dose palonosetron (0.75 mg) or granisetron (40 mg/kg) 30 minutes before chemotherapy, both in conjunction with dexamethasone. According to this study, the efficacy of palonosetron in preventing chemotherapy-induced vomiting is not inferior to that of granisetron in the acute phase (75.3% vs 73.3%), and is better than that of granisetron in the delayed phase (56.8% vs 44.5%; P<0.001) when administered in combination with dexamethasone.[23]

Aspinall and Goodman suggested that if active drugs are available, placebo-controlled trials are unethical because PONV are very much distressing after laparoscopic surgery.[24] In our study, three prominent 5-HT3RAs, namely ramosetron, palonosetron, and ondansetron, were used as antiemetics for the prophylaxis of PONV during the first 24 hours in patients undergoing LC. The number of complete responders was higher in the ramosetron group (P=0.034), while that in the ondansetron and palonosetron groups was comparable [Table 2]. In the early postoperative period (0–2 hours), the ramosetron group showed very less or almost no vomiting as compared with the ondansetron and palonosetron groups (P=0.037) [Table 4]. Therefore, ramosetron was a better antiemetic in this period. But, in the time periods 2–6 hours and 6–24 hours, there was no statistically significant difference between the vomiting episodes of the three groups. Parameters like intensity of nausea, retching, and requirements of rescue antiemetics were comparable in all groups, with no significant difference over the three time periods [Tables 3, 5 and 6].

CONCLUSION

Ramosetron 0.3 mg is a better choice as an antiemetic in the prophylaxis of PONV compared with ondansetron 8 mg and palonosetron 0.075 mg in the early postoperative period (0–2 hours) after LC.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.NIH Consensus conference. Gallstones and laparoscopic cholecystctomy. JAMA. 1993;269:1018–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fuji Y. The utility of Antiemetics and Treatment of postoperative nausea and vomiting in patients scheduled for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11:3173–83. doi: 10.2174/1381612054864911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang JJ, Ho ST, Liu YH, Lee SC, Liu YC, Liao YC, et al. Dexamethasone reduces nausea and vomiting after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Anaesth. 1999;83:772–5. doi: 10.1093/bja/83.5.772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Habib AS, Gan TJ. Evidence-based management of postoperative nausea and vomiting: A review. Can J Anaesth. 2004;51:326–41. doi: 10.1007/BF03018236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Candiotti KA, Kovac AL, Melson TI, Clerici G, Joo Gan T. A randomized, double-blind study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of three different doses of palonosetron versus placebo for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:445–51. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31817b5ebb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rabasseda X. Ramosetron, a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist for the control of nausea and vomiting. Drugs Today (Barc) 2002;38:75–89. doi: 10.1358/dot.2002.38.2.820104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wallenborn J, Kranke P. Palonosetron hydrochloride in the prevention and treatment of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Clinical medicine insights. Therapeutics. 2010;2:387–99. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muchatuta NA, Michael JP. Management of post-operative nausea and vomiting: Focus on palonosetron. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2009;5:21–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith I, Nathanson M, White PF. Sevoflurane - a long-awaited volatile anaesthetic. Br J Anaesth. 1996;76:435–45. doi: 10.1093/bja/76.3.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson YG, Rhodes M, Ahmed R, Daugherty M, Cawthorn SJ, Armstrong CP. Intramuscular diclofenac sodium for postoperative analgesia after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A randomised, controlled trial. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1994;4:340–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kerger KH, Mascha E, Steinbrecher B, Frietsch T, Radke OC, Stoecklein K, et al. Routine use of nasogastric tubes does not reduce postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2009;109:768–73. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181aed43b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gan TJ. Risk factors for postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2006;102:1884–98. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000219597.16143.4D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Macario A, Weinger M, Carney S, Kim A. Which clinical anesthesia outcomes are important to avoid.The perspective of patients? Anesth Analg. 1999;89:652–8. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199909000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim DK, Cheong IY, Lee GY, Cho JH. Low Pressure (8mmHg) Pneumoperitoneum does not Reduce the Incidence and Severity of Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting (PONV) following Gynecologic Laparoscopy. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2006;50:36–7. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tramer MR, Reynolds DJ, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Efficacy, dose-response, and safety of ondansetron in prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting: A quantitative systematic review of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Anesthesiology. 1997;87:1277–89. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199712000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ryu J, So YM, Hwang J, Do SH. Ramosetron vs ondansetron for the prevention of post-operative nausea and vomiting after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:812–7. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0670-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujii Y, Saitoh Y, Tanaka H, Toyooka H. Ramosetron for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting in women undergoing gynecological surgery. Anesth Analg. 2000;90:472–5. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200002000-00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fujii Y, Tanaka H. Double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study of ramosetron for the prevention of nausea and vomiting after thyroidectomy. Clin Ther. 2002;24:1148–53. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(02)80025-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feng FY, Zhang P, He YJ, Li YH, Zhou MZ, Cheng G, et al. Comparison of the selective serotonin3 antagonists ramosetron and granisetron in treating acute chemotherapy induced emesis, nausea, and anorexia: A single blind, randomized, crossover study. Curr Ther Res. 2000;61:901–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takenaka M, Okamoto Y, Ikeda K, Hashimoto R, Ueda T, Kurokawa N, et al. Comparison of anti-emetic efficacy of 5-HT3RA in orthopedics cancer patients receiving high dose chemotherapy. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2007;34:403–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuji Y, Saitoh Y, Tanaka H, Toyooka H. Ramosetron vs granisetron for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Can J Anesth. 1999;46:991–3. doi: 10.1007/BF03013138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim SI, Kim SC, Baek YH, Ok SY, Kim SH. Comparison of ramosetron with ondansetron for prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting in patients undergoing gynaecological surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2009;103:549–53. doi: 10.1093/bja/aep209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saito M, Aogi K, Sekine I, Yoshizawa H, Yanagita Y, Sakai H, et al. Palonosetron plus dexamethasone versus granisetron plus dexamethsone for prevention of nausea and vomiting during chemotherapy: A double-blind, double-dummy, randomized, comparative phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:115–24. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70313-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aspinall RL, Goodman NW. Denial of effective treatment and poor quality of clinical information in placebo control trials of ondansetron for postoperative nausea and vomiting: A review of published trials. BMJ. 1995;311:844–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7009.844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]