Abstract

Background:

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effect of two different volume of crystalloid given intraoperatively on postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV).

Materials and Methods:

Eighty adult patients of either sex belonging to ASA I and II class undergoing elective surgeries under general anesthesia for 1–2 h were studied in this prospective, randomized double blinded study. First group (group L) (n=40) received normal saline 4 mL/kg and second group (group H) (n=40) received 10 mL/kg of normal saline. This was in excess of the fasting requirement of the patients. No propofol or antiemetic drugs were given. PONV was evaluated by verbal descriptive score (VDS) [0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe, and 4 = unbearable]. Ondansetron (4 mg i.v.) was given if VDS score was 3 or more.

Results:

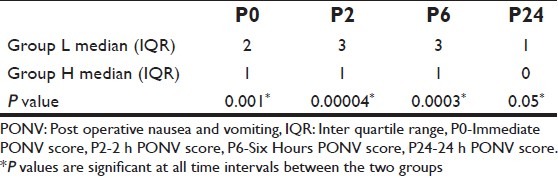

The median immediate PONV score was 2 and 1 in group L and H, respectively. The median 2 h PONV score in group L was 3 and in group H was 1. The median 6 h PONV score in group L was 3 and in group H was 1. The 24 h median postoperative PONV score was 1 and 0 in group L and H, respectively. In all these period of time the differences were statistically significant. The incidence of vomiting was more in group L [72.5% (29/40)] than in group H [30% (12/40)]. This was statistically significant (P=0.0003).

Conclusion:

From the current study it was concluded that patients who received larger volume of crystalloid intraoperatively have lesser incidence of PONV.

Keywords: Intravenous, normal saline, postoperative nausea vomiting

INTRODUCTION

Pain, nausea, and vomiting are frequently the most important concerns of the patient in the perioperative period. Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) is defined as one episode of nausea or vomiting within the first 24 h of surgery.[1] Overall incidence of PONV is in the range of 25–30%, with severe intractable PONV in approximately 0.18% of all patients undergoing surgery.[2]

Anesthetic factors contributing to PONV are opioids, anesthetic gases, and reversal of muscle relaxation with neostigmine in case of general anesthesia. The incidence of PONV is 10–20% in regional anesthesia.[2] The consequences of PONV include delay in oral intake leading to dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, cardiac rhythm disturbances, and increased intracranial and intraocular tension. Aspiration of gastric contents in the perioperative period is also an important concern.[2] Postoperative nausea and vomiting is a leading cause of unexpected admission to hospital following planned day surgery and delay in discharge.[3] Additional oxygen reduces the incidence of PONV by preventing the subtle intestinal ischaemia caused by anesthesia or surgery.[4,5] However, additional oxygen often fails to show its beneficial effect in low perfusion states. Preoperatively most patients are hypovolemic due to long overnight fasting and bowel preparation. Most of the studies used volume preloading with Hartman's solution or colloids[6,7] before induction of anesthesia and plasmalyte[8] and hetastarch[5,9] for prevention of PONV. Results of these studies are mostly conflicting. Primary hypothesis behind the present study is to show the beneficial effect of intraoperative normal saline volume infusion in addition to fasting requirement for prevention of PONV without preloading before induction of anesthesia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After approval of institutional ethical committee, eighty ASA 1 and 2 adult patients of both sexes undergoing elective nonlaparoscopic surgeries (total mastectomy with axillary clearance, epigastric, and inguinal hernia repairs, open cholecystectomy, appendectomy) of 60–120 min under general anesthesia were included in this double blind randomized trial. They were randomly allocated to either the high infusion group H (10 mL/kg) (n=40) or the low infusion group L (4 mL/kg) (n=40) using the Tippet random chart. The fluid infusion was in addition to the fasting requirement of the patients. Fasting requirement of fluid was calculated by 4-2-1 formula. The postoperative monitoring and the questioning were conducted by an anesthesiologist blinded to the intraoperative fluid regimen. Patients with Koivuranta's[10] score 1.95 or more were included in this study. Koivuranta's scoring system for PONV is an equation in which PONV = -2.21+.93g+0.82 h+0.59 ms+0.61 ns+0.75 d, where g = 1 for female and 0 for male, h = 1 if history of PONV is present and 0 if absent, ms = 1 if history of motion sickness present and 0 if absent, ns = 1 if nonsmoker and 0 if smoke and ds = duration of surgery over 60 min. Exclusion criteria were emergency surgery, patients on antiemetic medication and those with renal, hepatic, cardiovascular, and neurological dysfunctions.

An informed consent was obtained from all patients after explaining the risk involved and benefits of the study in their own language. In the operating room standard 5 leads electrocardiography, noninvasive blood pressure and pulse oxymetry were attached and baseline hemodynamic parameters were recorded. Two intravenous lines (16 G and 18 G) were secured in upper limbs and crystalloid (normal saline) was started for fasting requirement before the study fluid. Intravenous morphine 0.1 mg/kg was given for analgesia and anesthesia was induced with intravenous thiopentone 5 mg/kg and tracheal intubation was facilitated with intravenous vecuronium 0.1 mg/kg. Anesthesia was maintained with isoflurane in a mixture of nitrous oxide and oxygen (70:30). No propofol or antiemetic medication was given in intraoperative period. Intraoperative hypotension (decrease in mean arterial blood pressure by 20–30% of preoperative value for more than 10 min duration) and blood loss greater than 10% of estimated blood volume were noted. Diclofenac 1 mg/kg was given at end of surgery for post operative analgesia. Residual neuromuscular blockade was reversed with intravenous neostigmine 50 mcg/kg and glycopyrrolate 10 mcg/kg. No opioid was given at end of surgery and in postanesthesia care unit (PACU). All patients were given supplemental oxygen [FiO2 0.5] in PACU by venture mask. Severity of PONV was assessed by 5-point verbal descriptive scale (VDS)[11] in which 0 = no nausea, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe, and 4 = unbearable nausea. Postoperatively sedation was assessed with McMillan[12] sedation scoring system (1 = alert, 2 = awake but calm, 3 = drowsy but responding to verbal or tactile stimulation and 4 = asleep). Ondansetron (4 mg i.v.) was given if the VDS score was 3 or more. This was given only after ruling out all other causes of PONV such as hypoxia, hypotension, hypovolemia etc. Statistical analysis was done by using the Mann Whitney U test and the t test. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

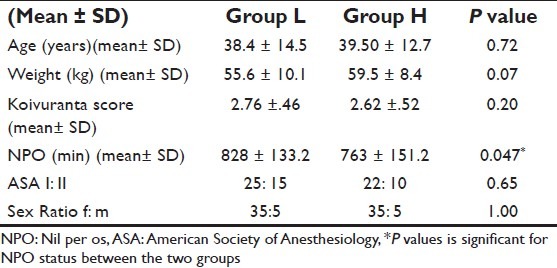

This study was done in a double blind, prospective randomized manner in 80 patients scheduled to undergo elective non laparoscopic surgeries under general anesthesia. The demographic data (age, weight, sex, and ASA grade) were comparable and statistically non significant [Table 1]. The mean duration of nil per os (NPO) in group L was 828 ± 133.2 min and in group H was 763 ± 151.2 min. The difference was statistically significant (P=0.047). The mean Koivuranta's score in group L was 2.8±0.5 and in group H was 2.6±0.5. The difference was not significant (P=0.218) [Table 1]. Randomization was successful in minimizing the effect of the variables on the outcome of the study.

Table 1.

Demographic data

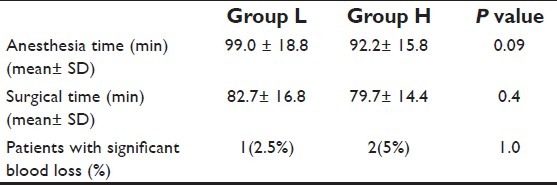

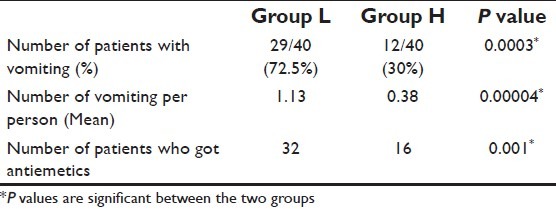

The mean anesthesia time, surgical time, and blood loss were comparable among both the groups and statistically nonsignificant [Table 2]. The incidence of vomiting was more in group L [72.5% (29/40)] than in Group H [30% (12/40)]. This was statistically significant (P=0.0003). The mean number of emetic episodes per person in group L was 1.1±0.9 and in group H was 0.4±0.6. This was statistically significant (P=0.00004). 32 out of 40 patients in group L received antiemetics postoperatively while 16 out of 40 patients in group H received antiemetics. This was statistically significant (P=0.001) [Table 3].

Table 2.

Intraoperative factors

Table 3.

Emetic episodes and rescue antiemetics

The median immediate, 2, 6, and 24 h PONV scores were statistically significantly different between group L and group H [Table 4].

Table 4.

Postoperative PONV scores (median)

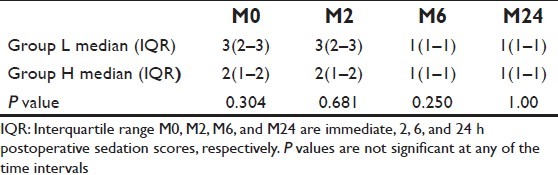

The median immediate, 2, 6, and 24 h postoperative sedation scores were comparable and statistically non significant [Table 5].

Table 5.

Postoperative sedation score (median)

DISCUSSION

Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) is a significant problem associated with general anesthesia, leading to discharge delay and patient distress.[13] Patients usually rank PONV above pain in terms of distress.[14] Various modalities have been used to prevent and treat PONV. These include medications, perioperative hydration, and acupressure.[15] The various drugs used includes phenothiazines, serotonin receptor antagonists, butyrophenones, antihistamines, and glucocorticoids.[2] In this study it was planned to find out the effect of intraoperative supplemental normal saline on PONV. To demonstrate a statistically significant decrease in PONV, we planned the study in a population susceptible to PONV. Apfel,[16] Koivuranta,[10] and Palazzo[17] use the scoring systems to identify such a population. These systems use the following as predictor variables: female gender, history of motion sickness or previous PONV, smoking, duration of surgery, and opioid use.

All three systems are of comparable accuracy. We used Koivuranta's system for its ease of use and accuracy.[18] This system takes into consideration female gender, history of PONV, history of motion sickness, smoking, and duration of surgery over 60 min.[10] This study was conducted in patients undergoing elective surgeries, throughout the year, encompassing all four seasons.

A total of 40 patients were included in each group. The low volume group had a 72.5% incidence of vomiting while the high volume group had a 30% incidence only. The difference was statistically significant (P=0.0003). This result is in accordance with Magner et al.,[19] who studied 141 ASA I females with 10 and 30 mL/kg of crystalloids. They found that the incidence of vomiting was less in the crystalloid-30group as compared to the crystalloid-10group (8.6% vs. 25.7%). The incidence of vomiting in 10 mL/kg (group H) in this study is comparable to the incidence of the 10 mL/kg group of Magner's study, but hyperchloraemic acidosis, 6% decrease in functional residual capacity, and 10% decrease in diffusing capacity was recorded in Magner's study. Also excessive fluid administration may result in pulmonary edema, electrolyte imbalance, cerebral edema, and death.[19] The possibility of these adverse effects made us undertake the study with lower fluid volumes. The incidence of number of emetic episodic were also significantly more in the group receiving less fluid (P=0.00004). This may be because of the gut hypoperfusion.[20] Intraoperative gut hypoperfusion is a risk factor for postoperative nausea and vomiting that may be due to an increase in 5-HT 3 in the gut mucosa.[20] Plasma volume expansion is associated with maintenance of gut perfusion and reduction in postoperative morbidity including postoperative nausea and vomiting.[20]

Causes of PONV can be central or peripheral. Central sensory stimuli are transmitted by the chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ), area postrema, and nucleus of the solitary tract to the vomiting center. The CTZ contains opioid and dopamine (D2) receptors which are emetogenic. Stimuli are relayed from the gut to the vomiting center via the vagus nerve that is a peripheral cause.[2] Use of opioids is associated with increased incidence of PONV.[21] Junger et al.[22] showed that administration of nitrous oxide increased the risk of PONV more than two-folds. Incidence of PONV with the newer volatile anesthetics (isoflurane and sevoflurane) was similar (30%) in a study by Apfel et al.[23] Neuromuscular blocking agents do not affect the incidence of PONV[24] but antagonism of residual neuromuscular block with neostigmine and atropine does result in increased emesis despite the antiemetic property of atropine.[25]

A number of investigators have shown that childhood after infancy and early adulthood are associated with an increased incidence of PONV.[6] The limitation of this study is that we could not analyze the effect of age as majority of patients were adults. BMI has not been proven to be a consistent risk factor for PONV.[2] Body weight was not a significant risk factor in this study.

Sedation scores were comparable between the two groups at all time intervals. This eliminated the possibility of the sedation causing a decreased incidence of vomiting. The PONV scores were significantly different at all time intervals between the two groups. The difference was maximal at the 2 h postoperative period. None of the patients in this study had any complications because of the fluid administration.

Koivuranta et al. found that ASA I patients were more predisposed to PONV compared to ASA III.[10] Including only ASA grade I and II patients is the limitation of this study. Also NPO period was found to be marginally significant in our study. This could have been a cause of the increased incidence of vomiting in the lower volume group. To find out the significance of the NPO period, either a larger sample should be taken for the study or the NPO duration should be similar for all the patients.

CONCLUSION

From the current study it was concluded that patients who received larger volume of crystalloid intraoperatively have lesser incidence of PONV. We found that the incidence of PONV and emetic episodes were less in patients who were given 10 mL/kg of normal saline intravenously compared to patients who received 4 mL/kg of normal saline.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Van den Bosch JE, Kalkman CJ, Vergouwe Y, Van Klei WA, Bonsel GJ, Grobbee DE, et al. Assessing the applicability of scoring systems for predicting postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anaesthesia. 2005;6:323–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2005.04121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kovac AL. Prevention and treatment of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Drugs. 2000;59:213–43. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200059020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wetchler BV. Postoperative nausea and vomiting in day-case surgery. Br J Anaesthesia. 1992;69:33S–9S. doi: 10.1093/bja/69.supplement_1.33s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greif R, Laciny S, Rapf B, Hickle RS, Sessler DI. Supplemental oxygen reduces the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesthesiology. 1999;91:1246–52. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199911000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gan TJ, Mythen MG, Glass PS. Intraoperative gut hypoperfusion may be a risk factor for postoperative nausea and vomiting. Br J Anaesthesia. 1997;78:476. doi: 10.1093/bja/78.4.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ali SZ, Taguchi A, Holtmann B, Kurz A. Effect of supplemental preoperative fluid on postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anaesthesia. 2003;58:775–803. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2003.03262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaudhary S, Sethi AK, Motiani P, Aditia C. Pre-operative intravenous fluid therapy with crystalloid or colloid on post operative nausea and vomiting. Indian J Med Res. 2008;127:577–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yogendran S, Asokumar B, Cheng DC, Chung F. A prospective randomized double-blinded study of the effect of intravenous fluid therapy on adverse outcomes on outpatient surgery. Anesth Analg. 1995;80:682–6. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199504000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mythen MG, Webb AR. Perioperative plasma volume expansion reduces the incidence of gut mucosal hypoperfusion during cardiac surgery. Arch Surg. 1995;130:423–9. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1995.01430040085019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koivuranta M, Laara E, Snare L, Alahuhta S. A survey of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anaesthesia. 1997;52:443–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1997.117-az0113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watcha MF, White PF. Postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesthesiology. 1992;77:162–84. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199207000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McMillan CO, Spahr-Schopfer IA, Sikich N. Premedication of children with oral midazolam. Can J Anaesth. 1992;39:545–50. doi: 10.1007/BF03008315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gold BS, Kitz DS, Lecky JH, Neuhaus JM. Unanticipated admission to the hospital following ambulatory surgery. JAMA. 1989;262:3008–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen MM, Duncan PG, DeBoer DP, Tweed WA. The postoperative interview : a0 ssessing risk factors for nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 1994;78:7–16. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199401000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fan CF, Tanhui E, Joshi E. Acupressure treatment for prevention of PONV. Anesth Analg. 1997;84:821–5. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199704000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Apfel CC, Laara E, Koivuranta M, Greim CA, Roewer N. A simplified risk scores for predicting postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesthesiology. 1999;91:693–700. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199909000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palazzo M, Evans R. Logistic regression analysis of fixed patient factors for postoperative sickness : A0 model for risk assessment. Br J Anaesth. 1993;70:135–40. doi: 10.1093/bja/70.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eberhart LH, Hogel J, Seeling W, Staack AM, Geldner G, Georgieff M. Evaluation of three risk scores to predict postoperative nausea and vomiting. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2000;44:480–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2000.440422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Magner JJ, McCaul C, Carton E, Gardiner J, Buggy D. Effect of intravenous crystalloid infusion on postoperative nausea and vomiting after gynaecological laparoscopy : Comparison of 30 and 10 ml/kg. Br J Anaesth. 2004;93:381–5. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeh219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gan TJ, Soppitt A, Maroof M, el-Moalem H, Robertson KM, Moretti E, et al. Goal directed intraoperative fluid administration reduces length of hospital stay after major surgery. Anesthesiology. 2002;97:820–6. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200210000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.James D, Justins D. Acute postoperative pain. In: Healy TEJ, knight PR, editors. A practice of Anaesthesiath. 7th ed. Arnold, London: Wylie and Churchill-Davidson's; 2003. p. 1221. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Junger A, Hartmann B, Benson M, Schindler E, Dietrich G, Jost A, et al. The use of an Anaesthesia information management system for prediction of antiemetic rescue treatment at the postanaesthetic care unit. Anesth Analg. 2001;92:1203–9. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200105000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Apfel CC, Kranke P, Katz MH, Goepfert C, Papenfuss T, Rauch S. Volatile anaesthetics may be the main cause of early but not delayed postoperative vomiting : A0 randomized controlled trial of factorial design. Br J Anaesth. 2002;88:659–68. doi: 10.1093/bja/88.5.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clarke RS. Nausea and vomiting. Br J Anaesth. 1984;56:19–27. doi: 10.1093/bja/56.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.King MJ, MIlzakiewicz R, Carli F, Deacok AR. Influence of neostigmine on postoperative vomiting. Br J Anaesth. 1988;61:403–6. doi: 10.1093/bja/61.4.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]