Abstract

Byssinosis is an occupational disease occurring commonly in cotton mill workers; it usually presents with features of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The management of patients with COPD presents a significant challenges to the anesthetist. Regional anesthesia is preferred in most of these patients to avoid perioperative and postoperative complications related to general anesthesia. We report a known case of Byssinosis who underwent nephrectomy under segmental spinal anesthesia at the low thoracic level.

Keywords: Anesthesia, byssinosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

INTRODUCTION

Byssinosis is one of the occupational diseases occurring commonly in cotton mill workers due to chronic exposure to cotton dust.[1] The pathophysiological changes in these patients are similar to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Anesthetic management in these patients presents a definitive risk of intraoperative and postoperative complications such as bronchospasm, laryngospasm, and prolonged mechanical ventilation respectively.[2] Atelectasis and ventilation–perfusion mismatch may adversely affect ventilation and oxygenation in intraoperative as well as the postoperative period.[3] The risk is markedly influenced by choice of the anesthetic technique. We report a case of byssinosis posted for radical nephrectomy, which was performed under the segmental thoracic subarachnoid block (Spinal) with epidural anesthesia.

CASE REPORT

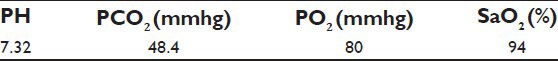

A 70-year-old male, retired textile mill worker, diagnosed case of byssinosis, presented to our Institute with fever, chills, and groin pain. Ultrasonography of abdomen and pelvis revealed right pyonephrosis, for which right radical nephrectomy was electively scheduled. Detailed history revealed that he suffered frequent respiratory tract infections with exacerbations, resulting in moderate functional impairment. At present he had dyspnea on routine household activities (NYHA Class I). He had history of hospital admissions on two previous occasions for acute onset dyspnea and was treated with bronchodilators and systemic steroids. At presentation, he was on tablet aminophylline (100 mg) twice a day and inhalable Fluticasone aerosol six hourly. Patient had no history of other co-morbid diseases. Arterial blood gas analysis on room air (FiO2 21%) was as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Preoperative blood gas analysis

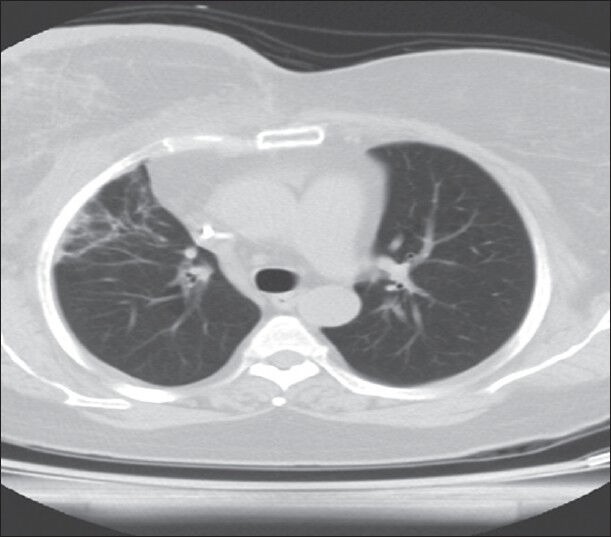

Chest-computed tomography showed fibrotic changes in upper lobar parenchyma of right lung [Figure 1]. Pulmonary function test and flow volume loop studies showed mild obstruction with decreased flow rates and poor post bronchodilator reversibility. After preoperative evaluation he was started on incentive spirometry, chest physiotherapy, and Asthalin Budecort nebulization for optimization of respiratory condition. After detailed discussion with surgeons, decision was taken to use regional anesthesia. On the day of surgery patient received his regular dosage of bronchodilators and steroids. Tablet Alprazolam (0.25 mg) was given on prior night for anxiolysis. Premedication was avoided. Preoperative baseline vitals were recorded with noninvasive monitors such as electrocardiogram, pulse oximetry, and noninvasive blood pressure monitor. A peripheral venous access was secured. A central venous access through internal jugular vein and invasive blood pressure monitoring by radial artery cannulation was secured under local anesthesia. Under all aseptic precautions, in the left lateral position, the combined spinal epidural (CSE) system was placed in 11th thoracic interspace using 16 G Touhy needle by the midline approach. The epidural space was identified by using “loss of resistance” to the air method. A 27G pencil point spinal needle was advanced through first needle until resistance to the dura mater was felt. The dura was pierced and the two needles secured together by a locking device. Once the flow of CSF had confirmed the correct placement 1 mL of 0.5% plain Bupivacaine mixed with 15 μg Fentanyl was injected before removing the spinal needle. The epidural catheter was threaded in place, the Touhy's needle was removed, the catheter taped in place, leaving 4 cm in the epidural space. Finally the patient was turned supine horizontal and oxygen at 5 L/min started with Hudson's mask. The heart rate, blood pressure, and SpO2 were recorded every min for 15 min and every 5 min thereafter. The episode of hypotension following the subarachnoid block was corrected with intravenous Ephedrine 5 mg bolus along with bolus of 100 mL of intravenous fluid. Upper and lower levels of sensory (pinprick) and motor block (modified Bromage scale) were recorded and assessed every 5 min. Once the block was considered adequate (minimum sensory block T6-T12 as accessed by pinprick method without any motor weakness in the legs or any signs of respiratory distress) and level of block was fixed; achieved at 20 min on both sides, patient was given slight left lateral tilt with wedge under back. For maintaining sensory level of T6, 0.25% Bupivacaine infusion was started at the rate of 4 mL/h. Intraoperative sedation was avoided. intraoperatively vitals were monitored. Total requirement of intravenous fluid was 2000 mL, calculated on the basis of conventional monitoring parameters. Duration of surgery was 11/2 h and was uneventful, causing no respiratory distress or hemodynamic compromise. The same extent of block was present at the end of surgery without lower limb weakness. Postoperative analgesia was maintained for next 2 days by continuous infusion of 0.125% plain Bupivacaine. Postoperative recovery was uneventful allowing patient to be discharged on fifth day.

Figure 1.

Preoperative chest CT of patient showing fibrotic changes in the right upper lobe

DISCUSSION

Byssinosis is an occupational disease due to chronic exposure to cotton dust or other vegetable fibers such as flax, hemp, with high preponderance in smokers. Chronic exposure results in irreversible changes in the respiratory system, arising from a Type III antigen antibody reaction.[4] It clinically resembles chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The pulmonary function test (PFT) shows increase in residual volume and decrease in FEV1, vital capacity, and FEV1: FVC < 70%.[5,6] Under general anesthesia, the altered pulmonary physiological changes noted in COPD, get exacerbated, due to cephalad movement of diaphragm, paralysis of intercostals muscles, and limited movement of the posterior diaphragm.[7] Hence, there is a high risk of pulmonary complications such as postoperative mechanical ventilation, respiratory distress syndrome, and frequent requirement of tracheostomy due to prolonged mechanical ventilation.[2] As a result, regional anesthesia becomes the preferred technique. A number of other regional techniques (paravertebral block or only epidural block) were also possible; however, segmental thoracic spinal anesthesia with epidural anesthesia was chosen,[8] because combining the subarchanoid block with the epidural block eliminates the possibility of inadequate muscle relaxation for surgery and provides good quality analgesia, eliminating the need for large doses of other systemic analgesics.[9] Our case was successfully managed under segmental thoracic spinal anesthesia with epidural anesthesia. But this approach will raise two major concerns, one being the risk of causing needle damage to the spinal cord in the thoracic region. This is primarily why spinal anesthesia was traditionally being performed in the lumbar region below the termination of the spinal cord. However, many studies performed using myelography showed that the thoracic cord lies anteriorly in theca while lumbar spinal cord is situated more dorsally. The space between the dura mater and the mid to lower thoracic spinal cord on its width is actually greater than that of epidural space in lumbar region because of lumbar enlargement, so lumbar spine is at greater risk of needle damage.[10,11] We suggest that patients chosen for this technique need to be evaluated carefully and the technique is to be reserved for experienced clinicians with a good learning curve.[12] Second concern is that the higher level of block in thoracic segments can affect ventilation adversely. However, diaphragm remains unaffected in this procedure as it is innervated from the cervical level (C3, 4,5). The forceful expiration and coughing can be affected due to paralysis of the muscles of the anterior abdominal wall. However, use of low dose of Bupivacaine preserves the coughing ability by causing minimal motor weakness of expiratory muscles.[12,13] The differential blocking effect of Bupivacaine, adequate fluid balance and avoiding central depression of circulation produces minimal hypotension. In conclusion our decision to perform spinal anesthesia in a modified way, if followed, may provide additional advantage to patients, in a selective subgroup, but further evaluation of the method is appropriate.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.McL Niven R, Pickering CA. Byssinosis: A review. Thorax. 1996;51:632–7. doi: 10.1136/thx.51.6.632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rutkowska K, Misiolek H. Perioperative management of COPD patients undergoingnonpulmonary surgery. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther. 2006;38:153–7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gruber EM, Tschernko EM, Kritzinger M, Deviatko E, Wisser W, Zurakowaski D, et al. The effect of Thoracic Epidural Analgesia with Bupivacain 0.5% on ventilator mechanics in patients with severe Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Anesth Analg. 2001;92:1015–9. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200104000-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor G, Massoud AA, Lucas F. Studies on the aetiology of Byssinosis. Br J Ind Med. 1971;28:143–51. doi: 10.1136/oem.28.2.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chattopadhyay BP, Saiyed HN, Mukherjee AK. Byssinosis Among Jute Mill Workers. Ind Health. 2003;41:265–72. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.41.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barreiro TJ, Perillo I. An Approach to Interpreting Spirometry. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:1107–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cabo FG, Grabac I, Nicola P, Kovacic K, Davor J, Malden J. Preoperative pulmonary evaluation for pulmonary and extrapulmonary operations. Acta Clin Croat. 2003;42:237–40. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clendenen SR, Wehle MJ, Rodriquez GA, Greengrass RA. Paravertebral block provides significant opiod sparing effect after hand assisted laproscopic nephrectomy: An expanded case report of 30 patients. J Endourol. 2009;23:1979–83. doi: 10.1089/end.2009.0095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi DH, Kim JA, Chung IS. Comparison of combined spinal epidural anesthesia and epidural anesthesia for cesarean section. Acta Anesthesiol Scant. 2000;44:214–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2000.440214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robertson HJ, Smith RD. Cervical myelography: Survey of modes of practice and major complications. Radiology. 1990;174:79–83. doi: 10.1148/radiology.174.1.2294575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yousem DM, Gujar SK. Are C1-2 Punctures for Routine Cervical Myelography below the Standard of Care? A JNR Am J Neyroradiol. 2009;30:1360–3. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Zundert AA, Stultiens G, Jakimowicz JJ, Van den Borne BE, Van der Ham WG, Wildsmith JA. Segmental spinal anesthesia for cholecystectomy in patient with severe lung disease. Br J Anesth. 2006;96:464–6. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Zundert AA, Stultiens G, Jakimowicz JJ, Van den Borne BE, Van der Ham WG, Wildsmith JA. Laproscopic cholecystectomy under segmental thoracic spinal anaesthesia: A fesibility study. Br J Anesth. 2007;98:682–7. doi: 10.1093/bja/aem058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]