Abstract

Congenital lobar emphysema (CLE) is a rare congenital anomaly of lung causing over aeration of one or more lobes of a histologically normal lung. It presents in infancy with respiratory distress due to compression atelectasis and often associated with mediastinal shift and hypotension. CLE poses a challenge in diagnosis and positive pressure ventilation due to air trapping. We report a case of 8-week-old infant with CLE posted for right lobectomy. Strategies to prevent misdiagnosis, over aeration and use of IPPV have been reviewed.

Keywords: Congenital lobar emphysema, lobectomy, positive pressure ventilation

INTRODUCTION

Congenital lobar emphysema (CLE) is a rare congenital malformation of the lung characterized by normal architecture with lobar over aeration and subsequent respiratory distress secondary to partial obstruction of the bronchus via the ball-valve effect. It is also known as congenital lobar over inflation or infantile lobar emphysema.[1,2] It presents as life threatening respiratory distress especially within the first 6 months of life due to compression atelectasis, mediastinal shift, hypoxia, and associated hypotension.[3,4] Aetiology is unknown for up to 50% cases, but several intrinsic and extrinsic causes have been described. Chest radiograph shows mediastinal shift and hyperinflation that is often confused with pneumonia and pneumothorax, even resulting in wrong placement of a chest drain.[5] Positive pressure ventilation or assist ventilation can worsen hyperinflation and hemodynamic collapse can ensue. We discuss the anesthetic management of an 8-week-old infant scheduled for right lobectomy with emphasis on prompt diagnosis and use of positive pressure ventilation in management of case of CLE.

CASE REPORT

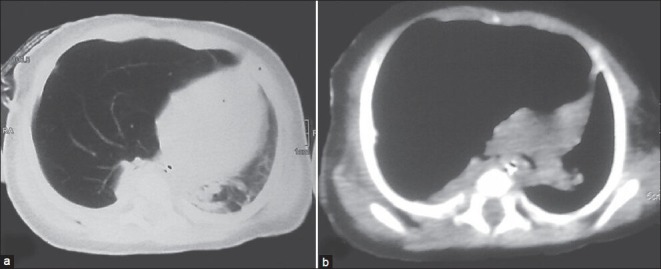

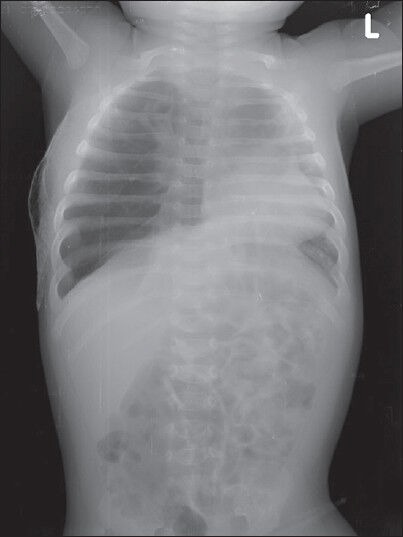

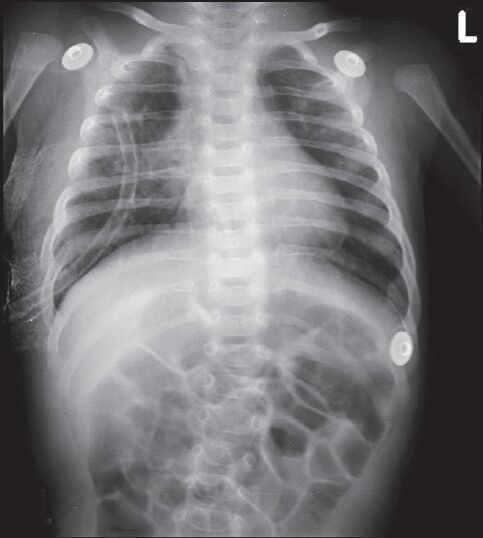

An 8-week-old male term infant weighing 4 kg presented to the paediatric emergency centre with complaints of intercostals retraction and tachypnoea of 60-70 breaths/min. The oxygen saturation (SpO2) on room air was 89%. He was born at 9 months of gestation via the vaginal route, weighing 3.1 kg and was breast-fed immediately. Hurried breathing was present since birth, but had aggravated since the past 25 days. Prior to current admission, the child was taken to a local hospital, where in view of respiratory distress and chest x-ray findings was misdiagnosed as right-sided pneumothorax and gastroenteritis. A right-sided intercostals drain (ICD) was introduced. As the symptoms persisted, CT scan was done that showed hyperinflation of right upper and mid lobes, pruned bronchovascular markings, mediastinal shift to left and atelectatic left lower lobes [Figure 1a and b]. A diagnosis of CLE was made; ICD was removed and referred to our centre. Repeat chest radiographs showed right mid and upper zone hyperinflation, mediastinal shift, and left lower zone atelectasis [Figure 2]. The infant was scheduled for right-sided lobectomy. Preoperative examination revealed a heart rate of 160 beats/min, a respiratory rate of 70 breaths/min, presence of intercostal and sternal recession; and hyper resonant percussion note on the right side. On auscultation, there were decreased breath sounds on the right side of the chest. There was no visible cyanosis and oxygen saturation (SpO2) was 89% on room air, 98% with nasal prongs (O2 at 2L/min). Routine hematological and biochemical investigations were within normal limits. Echocardiography ruled out any associated congenital cardiac anomalies. Oxygen supplementation was continued in the preoperative period and no premedication prescribed. An intravenous (IV) infusion of 5% dextrose in 0.9% saline was started at the rate of 16 mL/kg/h. Intraoperative monitoring included noninvasive blood pressure (NIBP), pulse oximetry (SpO2), electrocardiogram (ECG), capnography (EtCO2) and temperature. General anesthesia was induced with propofol 2 mg/kg and fentanyl 1 μgm/kg. After gentle-assisted check ventilation infant was paralyzed with atracurium 0.5 mg/kg. Gentle manual ventilation was performed via the face mask with oxygen and sevoflurane 1-2%, all the while maintaining preparedness for emergency thoracotomy. Endotracheal intubation was performed with 3.5 mm ID tube fixed at 9.5 cms. Position was confirmed by fibreoptic bronchoscopy. Maintenance was with oxygen, air, sevoflurane, intermittent positive pressure ventilation (IPPV). Pressure-controlled ventilation was used keeping airway pressure below 20 cm H2O. There were no signs of any pneumothorax and oxygen saturation maintained at 99-100% during this period. Infant was positioned in the left lateral position for a right thoracotomy. Analgesia was with titrated dose of fentanyl and intercostals nerve block using 0.25% bupivacaine. After resection of the middle lobe [Figure 3], right-sided ICD was placed with an underwater seal. Blood loss was insignificant. The collapsed lung tissue re-expanded and child had adequate respiratory efforts. Hence the infant was extubated at the end of surgery. Postextubation child was active, had regular and adequate spontaneous respiration and maintaining saturation of 95% on room air. Child was transferred to neonatal ICU for further monitoring and management. Postoperative chest radiograph done showed re-expansion of the left lower lobes and right intercostal drain in situ [Figure 4]. Intercostal drain was removed on the fourth postoperative day. Histopathology of the resected lobe showed dilated and thinned out alveoli. Infant was subsequently discharged on the 12th postoperative day.

Figure 1 (a and b).

CT scan showing hyperinflated right upper and mid lobes, pruned bronchovascular markings, mediastinal shift to left and atelectatic leftlower lobes

Figure 2.

Preoperative chest radiograph PA view showing right mid and upper zonal hypelucency, mediastinal shift to left and atelectasis of contralateral lung fields

Figure 3.

Specimen of the resected emphysematous right middle lobe

Figure 4.

Postoperative chest radiograph AP view showing expansion of lung fields, no mediastinal shift and intercostals drain in situ

DISCUSSION

CLE is a rare congenital anomaly characterized by over distention and hyperaeration of the affected pulmonary lobe by a check valve mechanism, with atelectasis of the remaining contralateral lung and cardiomediastinal shift.[6] CLE presents in the neonatal period up to 6 months of age. It is more common in males.[7] The incidence of left upper lobe involvement is 43% right middle lobe 32%, right upper- lobe 20%, and bilateral involvement 20%.[1] Pathology may be attributed to anomalies of the bronchial cartilage (reduced or absent bronchial cartilage resulting in intrinsic bronchial narrowing and bronchomalacia) or external bronchial compression from various causes resulting in air trapping.[8] CLE can be hypoalveolar (reduced number of alveoli) or polyalveolar (increased number of alveoli) that is diagnosed by histopathology. CLE may be diagnosed during prenatal ultrasound, but most commonly it is missed and is detected in neonates when progressive hyperinflation causes symptoms from compression of the remaining ipsilateral as well as the contralateral lung leading to cardiopulmonary compromise. Less severe, CLE may not present until later in infancy or childhood. Associated anomalies such as congenital heart disease are present in 10% of patients.[9] The child usually presents with rapid respiratory rate, tachycardia, and chest retractions, which worsens as progressive accumulation of gas in the affected lobe and progresses into respiratory distress and respiratory failure. There is asymmetric expansion of the hemithorax, rhonchi, displacement of apical impulse, hyper resonant percussion on affected side, and diminished breath sounds and heart sounds. Chest radiograph shows hyperinflation of involved lobe, atelectasis of contralateral lung, mediastinal shift, and flattening of ipsilateral diaphragm. This is often confused with pneumonia and pneumothorax, even resulting in wrong placement of a chest drain as in our patient. Hence, a high level of suspicion is needed to diagnose CLE. CT or a MRI scan is mandatory when in suspicion of CLE as it can prove life saving. Ventilation perfusion scans show reduced perfusion of affected lobe due to vessel compression and increased perfusion of normal lobes due to shunting. Conservative management has been used in the past; however, these patients invariably need resection of pathological lobes. Child can present for emergency or elective thoracotomy and lobectomy, in the lateral decubitus position. The physiological principles of ventilation and perfusion in thoracic surgery in lateral decubitus position for adults do not apply for infants. In infants with unilateral lung disease oxygenation will not improve with the diseased lung being nondependant and healthy lung being dependant, due to more lung compliance.[10] Anesthetic management in these neonates with borderline oxygenation and often with respiratory distress is challenging. Induction of anesthesia is the most crucial phase in the management of children with CLE. Excessive crying and struggling can increase the amount of trapped gas. Also, positive pressure ventilation or the positive airway pressure to assist the ventilation can also increase the emphysema, mediastinal shift and hemodynamic collapse can ensue.[6,11] Inhalational induction with maintenance of spontaneous respiration is commonly described for induction in CLE.[12] However we used intravenous induction and gentle assist ventilation after paralysis as the child came with intravenous line and our plan was intubation after paralysis. With use of muscle relaxation followed by gentle assist ventilation it was possible to control tidal volumes, respiratory rate, and avoid hyperinflation. Assist ventilation allowing spontaneous ventilation in inhalational induction can also increase the probability of over aeration. One lung ventilation is usually not required in neonates and infants as adequate exposure is achieved even with both lung ventilation.[13] The optimum ventilatory technique has been debated. Some advocate the avoidance of positive pressure ventilation.[6] Other useful techniques include pressure regulated volume controlled (PRVC) and high frequency ventilation.[14] As the neonate had signs of respiratory distress to start with and high work of breathing we decided to paralyze and use pressure control ventilation. We adopted pressure controlled ventilation keeping airway pressure below 20 cm H2O, thus controlling the delivered tidal volumes.[1] Careful monitoring of hemodynamic and lung dynamics is necessary with high degree of suspicion of pneumothorax. Anesthesia was maintained with inhalational agents. Nitrous oxide is avoided as it diffuses faster into closed cavities, further expanding the hyper inflated lobes.[15] Short acting opioids like fentanyl are preferred to prevent post operative respiratory depression. Analgesia can be provided using epidural catheter in caudal space and intercostals nerve blocks that can be administered under direct vision. In most cases, infants are extubated at end of procedure. Elective ventilation may be indicated when more than one lobe is excised or infant has poor spontaneous efforts. Lung protective ventilatory strategies should be continued in the event of post operative ventilation. In summary, CLE is life threatening condition posing various challenges to anesthesiologists, where prompt suspicion will help diagnose CLE and the use of IPPV may be useful technique for induction and ventilations.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stocker JT, Drake RM, Madewell JE. Cystic and congenital lung disease in newborn. Perspect Pediatr Pathol. 1978;4:93–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Landing BH, Dixon LG. Congenital malformations and genetic disorders of the respiratory tract (larynx, trachea, bronchi and lungs) Am Rev Respir Dis. 1979;120:151–85. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1979.120.1.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.al-Salem AH, Adu-Gyamfi Y, Grant CS. Congenital lobar Emphysema. Can J Anaesthe. 1990;37:377–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03005595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cote CJ. The anesthetic management of congenital lobar emphysema. Anesthesiology. 1978;49:296–8. doi: 10.1097/00000542-197810000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Franken EA, Buehl I. Infantile lobar emphysema: Report of two cases with unusual roentgenographic manifestations. Am J Roentgenol. 1966;98:354–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tempe DK, Virmani S, Javetkar S, Banerjee A, Puri SK, Datt V. Congenital lobar emphysema: Pitfalls and management. Ann Cardiac Anesth. 2010;13:53–8. doi: 10.4103/0971-9784.58836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Salem AH, Gyamfi YA, Grant CS. Congenital lobar emphysema. Can J Anaesthe. 1990;37:377–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03005595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berlinger NT, Porto DP, Thompson TR. Infantile lobar emphysema. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1987;96:106–11. doi: 10.1177/000348948709600124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lincoln JC, Stark J, Subramanian S, Aberdeen E, Bonham-Carter RE, Berry CL, et al. Congenital lobar Emphysema. Ann Surg. 1971;173:55–62. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197101000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Remolina C, Khan AU, Santiago TV, Edelman NH. Positional hypoxemia in unilateral lung disease. N Eng J Med. 1981;304:523–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198102263040906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tander B, Yalçin Y, Yilmaz B, Ali Karadao C, Bulu M. Congenital lobar emphysema: A clinicopathologic evaluation of 14 cases. Eur J Peciatr Surg. 2003;13:108–11. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-39589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nath MP, Gupta S, Kumar A, Chakrabarty A. Congenital lobar emphysema in neonates: Anaesthetic challenges. Indian J Anaesth. 2011;55:280–3. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.82688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hammer GB, Fitzmaurice BG, Brodsky JB. Methods for single lung ventilation in paediatric patients. Anaesth Analg. 1999;89:1426–9. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199912000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goto H, Boozalis ST, Benson KT, Arakawa K. High frequency jet ventilation for resection of congenital lobar emphysema. Anesth Analg. 1987;66:684–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raynor AC, Cap MP, Sealy WC. Lobar emphysema of infancy: Diagnosis, treatment and etiology aspects. Ann Thorac Surg. 1967;4:374–5. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)66527-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]