Abstract

Background and Objectives:

We evaluated the effect of adding dexmedetomidine to lidocaine and bupivacaine for peribulbar block in two different doses. The primary endpoints were the onset and duration of corneal anesthesia, globe akinesia, and duration of analgesia.

Materials and Methods:

A randomized controlled clinical trial was conducted on 90 ASA I-II patients scheduled for elective cataract surgery under peribulbar anesthesia. Patients were randomly allocated to one of three groups of 30 each; group C (control) received 3 ml of 2% lidocaine with 3 ml of 0.5% bupivacaine; group D50 received 3 ml of 2% lidocaine with 3 ml of 0.5% bupivacaine and 50 ug of dexmedetomidine; and group D25 received 3 ml of 2% lidocaine with 3 ml of 0.5% bupivacaine and 25 μg of dexmedetomidine.

Results:

The onset of corneal anesthesia and globe akinesia was significantly shorter in group D50 (P < 0.001) as compared to group C; however, in Group D25 onset of corneal anesthesia was significantly faster, but not onset of globe akinesia (P = 0.45). The duration of corneal anesthesia and globe akinesia was significantly longer (P < 0.001) in both Group D50 and Group D25 in comparison to Group C. Decrease in IOP was observed in both group D50 and group D25 at 5 minutes and 10 minutes following peribulbar block which was significant (P < 0.05) compared to group C.

Conclusion:

Addition of dexmedetomidine to lidocaine and bupivacaine in peribulbar block shortens the onset time and prolongs the duration of the block and postoperative analgesia. It also provides sedation which enables full cooperation and potentially better operating conditions.

Keywords: Cataract surgery, dexmedetomidine, peribulbar block

INTRODUCTION

Peribulbar block is commonly used for cataract surgery in adults,[1] most commonly local anesthetics were injected into peribulbar space, but using only local anesthetics for peribulbar anesthesia is associated with delayed onset of globe akinesia and corneal anesthesia,[2] short duration of analgesia and frequent need of block supplementation.[3] To decrease the time of onset of action and increase the duration of analgesia, many additives[4,5,6,7,8] such as clonidine, hyluronidase, sodium bicarbonate and adrenaline were added to local anesthetics with limited success.

Dexmedetomidine is centrally acting highly specific α2-agonist commonly used as sedative, preemptive analgesic[9] and to maintain stable hemodynamics in laparoscopic surgeries.[10] It also has been used has additives to local anesthetics in peripheral nerve block, brachial plexus block[11] and subarachnoid anesthesia, but none of the studies has been shown the effect of dexmedetomidine on peribulbar block for cataract surgery.

We therefore conducted a prospective, randomized control, double-blinded study to evaluate efficacy of dexmedetomidine on peribulbar anesthesia performed with either mixture of 0.5% bupivacaine and 2% lidocaine or 0.5% bupivacaine and 2% lidocaine with different doses of dexmedetomidine for cataract surgery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After local ethical committee approval and obtaining informed consent from patients, 90 American Society of Anaesthesiology (ASA) physical status I or II patients of either sex, aged 18-80 years scheduled for elective cataract surgeries under peribulbar block were prospectively enrolled in this study.

Patients with history of hypersensitivity to study drugs, significant cardiovascular disease (second [Mobitz II type] or third degree heart block, congestive heart failure, chronic heart failure (New York heart association [NYHA] III-IV), symptomatic coronary artery disease), uncontrolled hypertension, (body mass index [BMI]>35), uncontrolled diabetes (blood sugar >250 recorded in last 30 days or HbA1c >7.5%), chronic clonidine therapy, hepatic impairment (CHILD B or higher), renal impairment, ongoing drug or alcohol abuse, coagulopathy and pregnancy were excluded from study. Details of the anesthetic technique and study protocol were explained to the patients at the preoperative visit. Patients were not premedicated. No topical anesthetic or IV sedative medications were used before or during the block.

Using a computer-generated list, the subjects were randomly and evenly assigned into three groups (n_30): C, D50, and D25. All healthcare personnel providing direct patient care, and the subjects were blinded to the “study drugs” injected. All medications were prepared by anesthesiologists not participating in the study except for preparing the drugs. They received and kept the computer-generated table of random numbers according to which random group assignment was performed. According to the randomizing table, the drug to be injected in the peribulbar block was prepared in 10-ml syringes to equal volume of 6.5 ml in all three groups and labelled indicating only the serial number of the patient.

Standard monitoring consisting of intermittent noninvasive blood pressure, continuous electrocardiogram, heart rate, and pulse oximetry by Mindray Beneview T8 (Mindray Medical International Limited) were recorded. Hemodynamic variables were recorded every 5 min until completion of surgery.

The peribulbar block was performed by one of two authors (VRS and SMC) with substantial expertise in regional anesthesia for ophthalmic surgery.

Group-C patients received peribulbar anesthesia using a mixture of 3 ml of 2% lidocaine, 3 ml of 0.5% bupivacaine and 0.5 ml of normal saline.

Group D50 patients received peribulbar anesthesia using a mixture of 3 ml of 2% lidocaine, 3 ml of 0.5% bupivacaine and 50 μg of dexmedetomidine (50 μg in 0.5-ml saline).

Group D25 patients received peribulbar anesthesia using a mixture of 3 ml of 2% lidocaine, 3 ml of 0.5% bupivacaine and 25 μg of dexmedetomidine (25 μg in 0.5 ml saline). Each patient received total volume of 6.5 ml.

Peribulbar block was performed using 26-G, 13-mm short bevelled needle; the needle was inserted through the conjunctiva as far laterally as possible in the inferotemporal quadrant. Once the needle is under the globe, it was directed along the orbital floor, passing the globe's equator to a depth controlled by observing the needle/hub junction reach the plane of the iris. 3.5 ml of “study drug” was injected slowly; in the same way other 3 ml of “study drug” was injected at 2 mm medial and inferior to supra-orbital notch.[12] Gentle ocular massage was applied to eyeball to promote the spread of local anesthetic and to decrease the intraocular pressure (IOP), at the same time IOP was measured using indentation tonometry at 5 min before injection and 1, 5 and 10 minutes after injection. Corneal sensation was evaluated using cotton wick at every 30 seconds till the onset of anesthesia and every 15 minutes till recovery. Ocular movement was evaluated at 2-minute interval in all four directions using 3-point scale. 0-complete akinesia, 1-limited movement, 2- normal movement.[4] Time for adequate conditions to start the surgery was defined as presence of corneal anesthesia together with the total ocular movement score ≤1 and eyelid squeezing score of 0. If a block is inadequate for more than 10 min after injection of “study drug”, additional injection with 2 ml of lidocaine 2% injected inferotemporally.

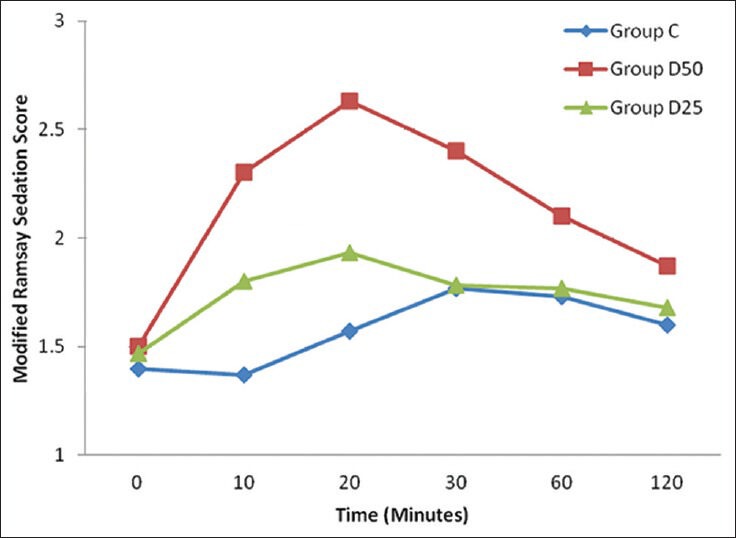

Sedation levels were assessed with modified Ramsay sedation scale (1-Anxious and agitated or restless or both, 2-Cooperative, oriented, and tranquil, 3-Responds to commands only, 4-Brisk response to light glabellar tap or loud auditory stimulus, 5-No response to light glabellar tap or loud auditory stimulus) at every 10 minutes during surgery and every 30 minutes in first 2 hours.

Duration sensory and motor block was assessed by onset of pain and recovery of eyeball movement respectively. At the same time on the first postoperative day, the following variables were also recorded: Degree of pain (by using a 5-points verbal rating score: 0-no pain, 1-mild pain, 2-moderate pain, 3-severe pain, 4-unbearable pain). The pain was assessed at the end of surgery and every 60 mins up to 2 h and then at 6 h and 24 h. A tablet of paracetamol 500 mg was given if a verbal rating scale score was ≥2. The time of first request for analgesic and total analgesic requirement in 24 hrs was recorded.

Statistical analysis

To calculate the required study size, we took into account the results of a previous pilot study with 15 patients per group (unpublished observations). Accepting a one-tailed α-error of 5%, a β error of 5% and power of 90%.[13] Based on these calculations, the required study size was 30 patients per group.

Statistical analysis was performed using the program GraphPad prism software package v. 5 (GraphPad Inc., CA, USA). Numerical variables were presented as mean and standard deviation (SD) and categorical variables were presented as frequency (%). One-way ANOVA was used for between-group comparisons of numerical variables, if its assumptions were fulfilled, otherwise for nonparametric, the Kruskal–Wallis test was used. Tukey's HSD test or the Mann–Whitney test was used, whenever appropriate, as post-hoc tests. χ2 test was used for between-group comparisons between categorical variables. A P value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

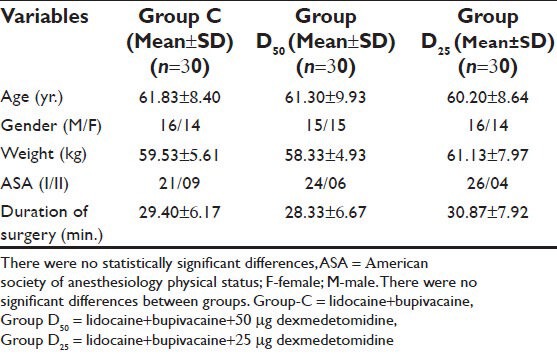

Patient characteristics and duration of surgery were similar in all three groups [Table 1]. No differences in baseline hemodynamic variables, IOP and peripheral SpO2 were reported between the three groups (data not presented). The incidence of successful block was also comparable in all the groups. In Group D50, intraoperative mean heart rate was found to be lower up to 60th min (P = 0. 032) and arterial pressure lower up to 30th min (P = 0.049). One dose of atropine (0.3 mg) was needed in six patients in Group D50. However, there was no need to administer ephedrine to any patients.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics, duration of surgery

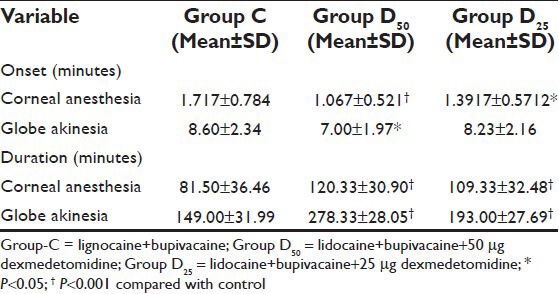

The onset of corneal anesthesia and globe akinesia was significantly shorter in group D50 (P < 0.001) as compared to group C but in Group D25 onset of corneal anesthesia was significantly faster but not globe akinesia (P = 0.45) as compared to Group C. The duration of corneal anesthesia and globe akinesia was significantly higher (P < 0.001) in both Group D50 and Group D25 in compared to Group C [Table 2].

Table 2.

Onset and duration of corneal anesthesia and globe akinesia

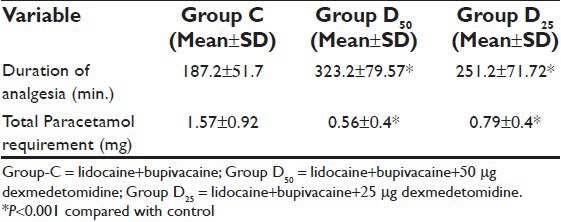

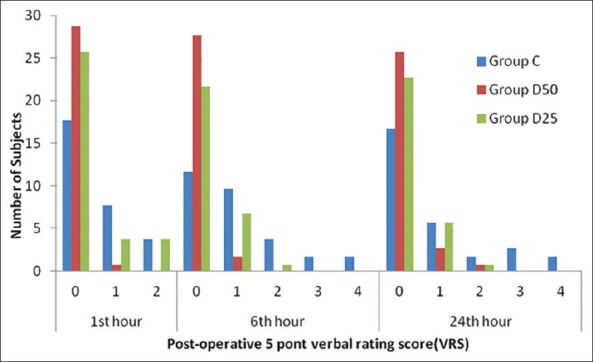

Resolution of motor blockade required >6 h in 24 patients in the group D50 (80%) and 20 patients in the group D25 (66%) as compared to 14 patients in Group C (47%). Duration of postoperative analgesia was longer in Group D50 (P < 0.001) and group D25 (P < 0.001) in comparing to Group C. These patients also required significantly (P < 0.001) smaller doses of rescue analgesic during 24 hours [Table 3]. The number of patients with no pain was always higher in the group D50 (1 h: 29 [96%]; 6 h: 28 [93%]; 24 h: 26 [86%]) and group D25 (1 h: 26 [93%]; 6 h: 22 [73%]; 24 h: 23 [76%]) than in the group C (1 h: 18 [60%]; 6 h: 12 [40%]; 24 h: 17 [56%]) [Figure 1]. During the first day after surgery 17 patients in Group C (56%), 26 patients in the group D50 (86%), 24 patients in the group D25 (66%) did not require pain medication; this difference statistical significant (P < 0.0001, P < 0.0001).

Table 3.

Duration of analgesia and postoperative analgesic requirement

Figure 1.

5 point Verbal rating scale score measured 1, 6, and 24 h after surgery in patients receiving peribulbar anaesthesia in Group-C (n-30), Group D50 (n-30) and Group D25 (n-30)

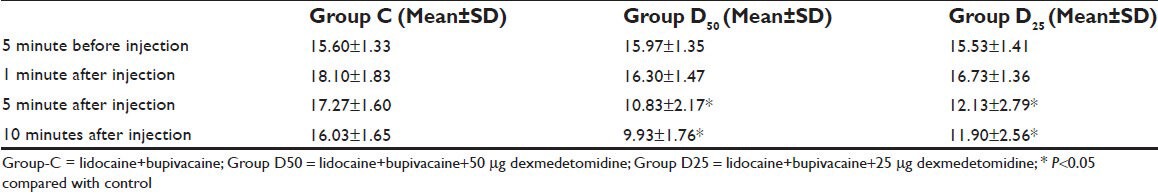

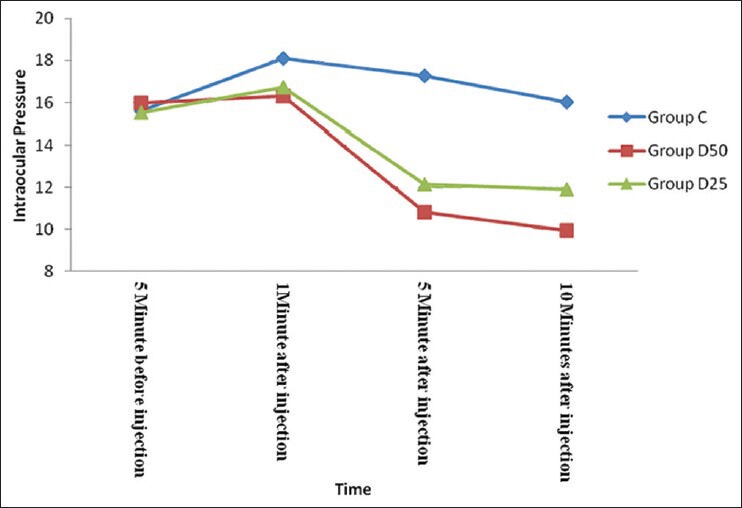

IOP was increased significantly (P < 0.001) in group C at 1 minute after injection as compared to group D50 and D25 where an increase in IOP was minimal and not statistically significant (P = 0.21 /P = 0.17). Decrease in IOP was observed in both group D50 and group D25 at 5 and 10 minutes following peribulbar block which was significant (P < 0.05). However, in group C IOP was significantly above the baseline both at 5 and 10 minutes following injection [Table 4, Figure 2].

Table 4.

Changes in intraocular pressure (mmHg)

Figure 2.

Graphical representation of intraocular pressure changes during first 10 minutes after peribulbar injection. Data presented as mean IOP (mmHg). Decrease in IOP was observed in both group D50 and group D25 at 5 minutes and 10 minutes following peribulbar block which was significant (P<0.05)

Mean Ramsay sedation score (RSS) in group D50 was significantly higher than both group C and group D25 till first 60 minutes after injection. However, in Group D25 RSS scores were higher than group C till first 20 minutes after injection [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Graphical presentation of Ramsay sedation score during first 120 minutes. Sedation scores in Group D50 were significantly higher between 10 to 60 minutes as compared to control group. In group D25 sedation scores were higher than control group till first 20 minutes

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrated that in patients undergoing peribulbar anesthesia for cataract surgery, dexmedetomidine, added to local anesthetics in two different doses, shortens corneal anesthesia and globe akinesia onset time and extends block duration.

In peribulbar anesthesia, though it has been demonstrated in some studies that clonidine added to local anesthetics extended the duration of anesthesia and increased the quality of the block,[4] in their study with 1.5-μg/kg clonidine to Mepivacaine 3%-Hyaluronidase solution, Hala M et al.,[4] reported that there was no significant difference regarding sensory and motor block onset time. However, in this study we found that the onset of sensory and motor block period was shorter in the dexmedetomidine group than in group without dexmedetomidine.

The mechanism by which α2-adregenic receptor agonist produces analgesia and sedation is not fully understood but is likely to be multifactorial. Peripherally, α2-agonist produces analgesia by reducing the release of norepinephrine and causing α2-receptor-independent inhibitor effect on nerve fiber action potential. Centrally, α2-agonists produce analgesia and sedation by inhibition of substance P release in the nociceptive pathway at the level of the dorsal root neuron and by activation of α2-adrenoreceptor in the locus coeruleus.[14,15]

There is a significant decrease in the IOP in the dexmedetomidine groups in our study. Madan R et al.[16] found the similar result when added Clonidine to Lidocaine in cataract surgery done by peribulbar block.

The effect of dexmedetomidine on the IOP may be due to its direct vasoconstrictor effect on the afferent blood vessels of the ciliary body leading to reduction of aqueous humor production.[17] It may also facilitate the drainage of aqueous humor by reducing sympathetically mediated vasomotor tone of the ocular drainage system.[18] Finally, the hemodynamic effect of dexmedetomidine can be responsible for reduction of IOP.[19]

This study demonstrates that addition of local anesthetic with dexmedetomidine provides sedation effectively without causing respiratory depression. Dexmedetomidine sedation enables full cooperation and potentially better operating conditions without significant respiratory depression.[20]

CONCLUSIONS

Dexmedetomidine is a useful drug in combination with bupivacaine and lidocaine in peribulbar anesthesia, as it shortens sensory and motor block onset time, extends motor and sensory block durations, extends the analgesia period, significantly decreases the IOP and provides sedation which enables full cooperation and potentially better operating conditions.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stead SW, Beatie DB, Keyes MA. Anesthesia for ophthalmic surgery. In: Longnecker DE, Tinker JH, Morgan GE Jr, editors. Principles and practice of anesthesiology. St Louis: Mosby; 1998. pp. 2181–99. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rubin AP. Complications of local anaesthesia for ophthalmic surgery. Br J Anaesth. 1995;75:93–6. doi: 10.1093/bja/75.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong DH. Regional anaesthesia for intraocular surgery. Can J Anaesth. 1993;40:635–57. doi: 10.1007/BF03009701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hala M, Bahy Eldeen, Mona R, Faheem, Dalia Sameer, Ayman Shouman. Use of clonidine in peribulbar block in patients undergoing cataract surgery. Aust J Basic Appl Sci. 2011;5:247–50. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abdellatiff AA, El Shahawy MA, Ahmed AI, Almarakbi WA, Alhashemi JA. Effect of low-dose rocuronium on quality of peribulbar anesthesia for cataract surgery. Saudi J Anaesth. 2011;5:360–4. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.87263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarvela PJ. Comparision of regional ophthalmic anaesthesia produced by Ph-adjusted 0.75% and 0.5% bupivacaine and 1% and 1.5% etidocain, all with hyluronidase. Anesth Analg. 1993;77:131–4. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199307000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zahl K, Jordan A, McGroarty J, Sorensen B, Gotta AW. pH-adjusted bupivacaine and hyaluronidase for peribulbar block. Anesthesiology. 1990;72:230–2. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199002000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reah G, Bodenham AR, Braithwaite P, Esmond J, Menage MJ. Peribulbar anesthesia using a mixture of local anaesthetic and vecuronium. Anaesthesia. 1998;53:551–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.1998.00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kemp KM, Henderlight L, Neville M. Precedex: Is it the future of cooperative sedation? Nursing. 2008;38:7–8. doi: 10.1097/01.NURSE.0000314838.93173.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhattacharjee DP, Nayek SK, Dawn S, Bandopadhyay G, Gupta K. Effects of dexmedetomidine on haemodynamics in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy- A comparative study. J Anaesthesia clin pharmacol. 2010;26:45–8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gandhi RR, Shah AA, Patel I. Use of dexmedetomidine along with bupivacaine for brachial plexus block. Natl J Med Res. 2012;2:67–9. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar CM, Dodds C. Evaluation of Greenbaum sub-Tenon's block. Br J Anaesth. 2001;87:631–3. doi: 10.1093/bja/87.4.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Browner WS, Black D, Newman B, Hulley SB. Estimating sample size and power. In: Hulley SB, Cummings SR, editors. Designing clinical research: An epidemiologic approach. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1988. pp. 139–50. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eisenach JC, De Kock M, Klimscha W. Alpha (2)-adrenergic agonists for regional anesthesia. A clinical review of clonidine (1984-1995) Anesthesiology. 1996;85:655–74. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199609000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo TZ, Jiang JY, Buttermann AE, Maze M. Dexmedetomidine injection into the locus ceruleus produces antinociception. Anesthesiology. 1996;84:873–81. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199604000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Madan R, Bharti N, Shende D, Khokhar SK, Kaul HL. A dose response study of Clonidine with local anesthetic mixture for peribulbar block: A comparison of three doses. Anesth Analg. 2001;93:1593–7. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200112000-00056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Macri FJ, Cervario SJ. Clonidine. Arch Ophthalmol. 1978;96:2111–3. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1978.03910060491022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vartianinen J, MacDonald E, Urtti A, Ronhiainen H, Virtanen R. Dexmedetomidine induced ocular hypotension in rabbits with normal or elevated intraocular pressure. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992;33:2019–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Georgiou M, Parlapani A, Argiriadou H, Papagiannopoulou P, Katsikis G, Kaprini E. Sufentanil or clonidine for blunting the increase in intraocular pressure during rapid sequence induction. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2002;19:819–22. doi: 10.1017/s0265021502001321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muttu S, Liu EH, Ang SB, Chew PT, Lee TL, Ti LK. Comparison of dexmedetomidine and midazolam sedation for cataract surgery under topical anaesthesia. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2005;31:1845–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2005.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]