Abstract

Aim:

Primary To compare effect of 30 ml/kg and 10 ml/kg crystalloid infusion on post-operative nausea and vomiting after diagnostic gynaecological laparoscopy. Secondary To correlate incidence of post-operative nausea and vomiting associated with different phases of menstrual cycle.

Study Design:

This prospective, randomized, double blinded study was conducted in 200 patients [Group I - 10 ml.kg-1 crystalloid infusion (n = 100) and Group II - 30 ml.kg-1 crystalloid infusion (n = 100)] of ASA grades I/II, of either sex in the age group 20-40 years undergoing ambulatory gynaecological laparoscopic surgery. Both groups were compared with respect to post-operative nausea vomiting, hemodynamic parameters and incidence of post-operative nausea and vomiting associated with different phases of menstrual cycle.

Statistical Analysis:

Data for categorical variables and continuous variables are presented as proportions and percentages and mean ± SD, respectively. For normally distributed continuous data, the Student t test was used to compare different groups. Categorical data were tested with the Fisher exact test. Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficients for data normally distributed and not normally distributed, respectively, were used to evaluate the relation between 2 variables. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results:

In the first 4 h after anaesthesia, the cumulative incidence of nausea and vomiting in Group I was 66% as compared to 40% in Group II (P value = 0.036, *S). Anti-emetic use was less in the group II as compared to Group I (13% vs. 20%, P = 0.04). Female patients in the menstrual phase experienced nausea and vomiting in 89.48% of cases as compared to 58.33% and 24.24% during proliferative and secretory phases of menstrual cycle, respectively.

Keywords: Ambulatory surgery, fluids, menstrual cycle, nausea and vomiting, IV crystalloid

INTRODUCTION

Post-operative nausea and vomiting (PONV) continues to be a common complication after ambulatory surgery.[1] Although, some advocate prophylactic anti-emetic therapy for high risk patients with rescue anti-emetic treatment for episodes of PONV, the optimal approach remains obscure. Despite introduction of new anti-emetic medication and short acting opioids and anaesthetics, 20-70% of surgical patients still experience PONV[2] and universal pharmacological PONV prophylaxis does not seem to be cost effective.[1] PONV can lead to high levels of patient distress, dissatisfaction[3] and may lead to increased health care costs, increased recovery room time, expanded nursing care and the need for overnight hospital admission.[3,4] There remains a need to develop cost-effective, ideally non-pharmacological, strategies to decrease the incidence of PONV, especially in high risk patients. Psychometric and stress assessment[5] tests to evaluate the patient satisfaction and feeling of well being after general anesthesia revealed that a significant improvement could be achieved by reduction of PONV. Advances in surgical techniques have shown a trend towards standard open procedures being modified to become less invasive and shorter in duration. Patients predominantly incur a fluid deficit due to mandatory preoperative fasting and therefore, guided intravenous (IV) fluid therapy, targeted towards replacement of the pre-operative volume deficit, may improve clinical anesthesia outcomes and reduce the incidence of PONV.[6] The last menstrual dates (LMP) of all 200 subjects were noted, as previous studies have shown correlation between different phases of menstrual cycle and PONV in women.[7] This study is designed to compare the infusion of balanced salt solution at 30 ml.kg-1 and 10 ml.kg-1 with respects to incidence of PONV and to correlate various phases of menstrual cycle with incidence of PONV in healthy women undergoing ambulatory gynaecological laparoscopic surgery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The present study was conducted after obtaining approval from the Hospital Ethical Committee and a written informed consent from the patients. This prospective, randomized, double blinded study was conducted on 200 patients of ASA physical status I/II, of either sex in the age group of 20-40 years, who were scheduled to undergo ambulatory, elective gynaecological laparoscopic surgery in the supine position under general anesthesia with controlled ventilation. Patients were randomized according to the contents of a sealed envelope labelled Group I and Group II.

Exclusion criteria

Patient's with hypertension, diabetes, history of congestive cardiac failure, valvular heart disease, motion sickness, epilepsy, hemoglobin level <10gm %, relevant drug allergy and undergoing procedure involving more than a diagnostic laparoscopy surgery were excluded from the surgery. Patient's who have received anti-emetic medication within 24 h prior to surgery and intraoperative events like hypotension and excessive blood loss during surgery were omitted from the analysis.

Anesthetic technique

A detailed pre-anesthetic check-up was done one day prior to surgery. Details of patient's clinical history, LMP and physical examination were noted. Baseline investigations included complete hemogram, random blood sugar, urine routine and microscopy and chest X-ray (PA view). All patients were made to fast overnight and were administered tab. Alprazolam 0.25 mg orally at 10 pm on the night before surgery. For the purpose of study, patients were randomly divided into 2 groups: Group I (n = 100) received 10 ml.kg-1 compound sodium lactate (CSL) and Group II (n = 100) received 30 ml.kg-1 CSL. To maintain patient and investigator blinding, I.V. fluid administration was initiated in the preoperative area by the investigator, who inserted an 18G I.V. cannula and attached 500 ml CSL to it. The investigator did not see the patient again until they were shifted to the Post Anesthesia Care Unit (PACU). In all patients, fluid was administered to the patient according to body weight in the preoperative area and continued in the operating theatre and completed by the end of 1 h. Patients returned to the PACU without fluids attached and neither the patient nor the investigator was aware of the volume given or the group allocation. After attaching the monitors to the patient, baseline parameters (SpO2, ECG lead II, heart rate, systolic, diastolic, mean BP and respiratory rate) were noted. All patients received paramedication with Midazolam 1-2 mg I.V. bolus and Ranitidine 50 mg I.V. in operation theatre. Anesthesia was induced with Fentanyl (2 μg.kg-1) I.V. and Propofol (2-2.5 mg.kg-1) I.V. Neuromuscular block was achieved with Vecuronium Bromide 0.08-0.1 mg.kg-1 I.V. Patients were ventilated via face mask with N2O 70% and 0.4% Isoflurane in O2 for 180 seconds before endotracheal intubation was done and an oro-gastric tube of 14 French gauge was inserted. Anesthesia was maintained with N2O/O2 mixture (2:1), 1% Isoflurane and intermittent boluses of Vecuronium administered I.V. for neuromuscular blockade. During anesthesia hemodynamic parameters (SpO2, ECG lead II, heart rate, systolic, diastolic, mean BP and respiratory rate) were monitored and recorded every 5 min. Ventilation technique was aimed at maintaining oxygen saturation between 98-100% and end tidal CO2 between 30 and 40. Diclofenac Sodium (Justin) 75 mg I.V. was given to all patients as routine analgesia intraoperatively. At the end of surgical procedure anesthesia was discontinued, muscle relaxation was reversed with Neostigmine (0.05mg. kg-1) I.V. and Glycopyrrolate (0.01 mg. kg-1) I.V. Patients were questioned after regaining full consciousness and assessed for PONV and pain every half hourly in PACU until 4 h. Fentanyl 50 μgm I.V. bolus was given to patients who complained of pain and repeated after 15 min if required.

Nausea was graded as follows[8]

0 No nausea

1 Nausea only

2 Retching/1 episode of vomiting

3 > 1 episode of vomiting

Grades of nausea and rescue anti-emetic regimen were documented for all patients till 4 h after anesthesia. As the discomfort experienced due to nausea is subjective, rescue anti-emetics were given only on occurrence of symptoms and not on demand. Rescue anti-emetic in the form of Ondansetron 4mg I.V. was given for grades 2 and for patients who progressed to grade 3, Metoclopramide 10mg I.V. was added. Oral fluids were allowed after 4 h.

Statistical analysis

At the end of the study, all documented data was statistically analyzed. Data for categorical variables was presented as proportions and percentages. Data for categorical variables and continuous variables are presented as proportions and percentages and mean ± SD, respectively. For normally distributed continuous data, the student t-test was used to compare different groups. If data points were not normally distributed, Mann-Whitney U tests were used. Categoric data were tested with the Fisher exact test. Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficients for data normally distributed and not normally distributed, respectively, were used to evaluate the relation between 2 variables. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and SPSS 14.0 for Microsoft Windows (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, IL). P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

OBSERVATION AND RESULTS

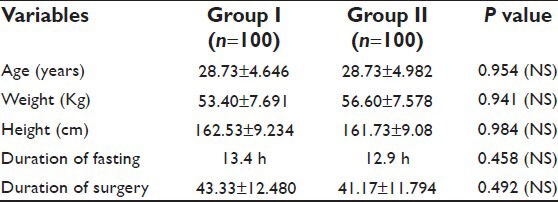

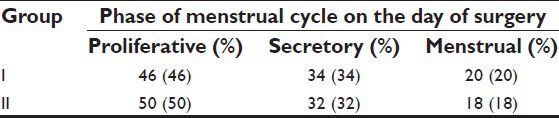

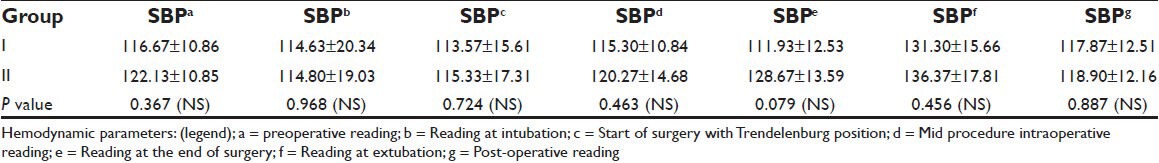

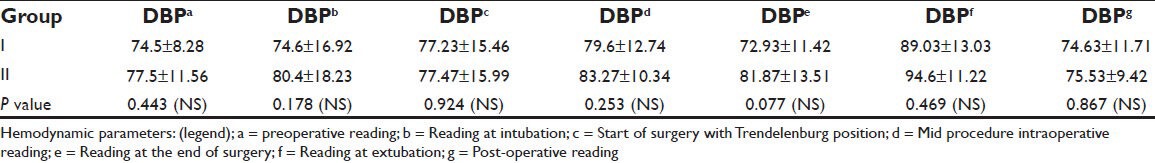

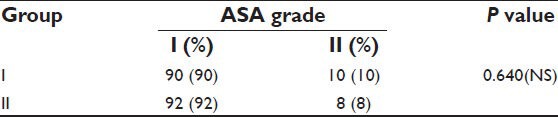

Demographic profiles of the patients’, duration of fasting and surgery, ASA status and phases of menstrual cycle of patients in both the groups were similar [Tables 1–3]. Heart rate (HR), systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were recorded at 7 instances during surgery. HR in both groups was comparable. BP was found to be higher in patients belonging to Group II at the end of surgery. However, no significant changes were recorded at any other time [Tables 4 and 5]. Other parameters, like SpO2 and EtCO2 also did not show any marked difference between the two groups. SpO2 was maintained at 98 -100% at all times during and after surgery. EtCO2 was kept between 28 and 40 from the beginning till the end of surgery. No episode of hypercapnia or desaturation was observed during the conduct of anesthesia and during post operative period.

Table 1.

Demographic data and duration of surgery

Table 3.

Phase of menstrual cycle on the day of surgery

Table 4.

Systolic blood pressure

Table 5.

Diastolic blood pressure

Table 2.

ASA status

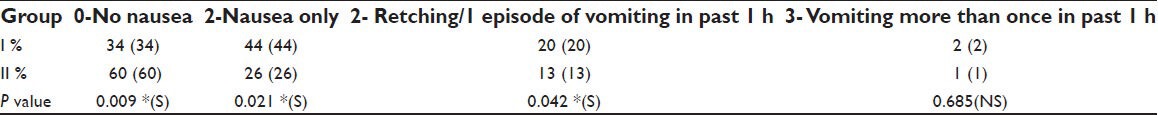

The incidence of nausea was 44% in Group I and 26% in Group II, a result which was statistically significant (P = 0.021, *S; Table 6). Twenty patients in Group I progressed to Grade 2 without rescue anti-emetics while only 13 patients were grade 2 category in Group II, a difference which was significant (P = 0.042, *S; Table 6). The cumulative incidence of nausea and vomiting in Group I was 66% as compared to 40% in Group II (P = 0.036, *S; Table 6). Twelve out of 50 patients in Group I required post-operative analgesia, which was administered in the form of 50 μgm Fentanyl I.V. in PACU. Five of these patients required rescue anti-emetics. In Group II, 8 patients were administered Fentanyl 50 μgm I.V. for analgesia out of which 2 patients required rescue anti-emetic therapy. The opioid consumption and post-operative analgesia were comparable in both groups.

Table 6.

Grading of nausea and vomiting

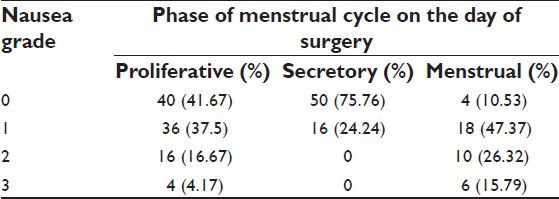

We also found a high incidence between PONV and women in the menstruating phase. Female patients in the menstrual phase experienced nausea and vomiting in 89.48% of cases as compared to 58.33% and 24.24% during proliferative and secretory phases of menstrual cycle, respectively [Table 7].

Table 7.

Menstrual phase and grading of nausea and vomiting

DISCUSSION

This prospective, randomized, double blind clinical study is based on a pilot study.[6] The mechanism by which supplemental fluid therapy reduces PONV remains unknown. On basis of the observations and data analysis, we found out that intraoperative administration of 30 ml.kg-1 CSL compared with 10 ml.kg-1 CSL significantly reduced the incidence of nausea and vomiting post-operatively. Perioperative hypoperfusion of the gut mucosa owing to hypovolemia and consequent ischemia results in the release of serotonin, one of the most potent triggers of PONV.[9] Most of the patients are hypovolemic before the induction of anaesthesia due to overnight fasting.[10] Euvolemia is not achieved, until the post-operative period and by that time factors causing nausea/vomiting are well established. Bowel mucosal perfusion may be a factor in PONV and oesophageal Doppler studies have reported that goal directed fluid therapy aimed at maintaining stroke volume may lead to return of bowel function, decreasing the length of hospital stay and reducing the incidence of PONV.[11] Supplemental fluid load most likely decreases the volume deficit leading to a positive effect on splanchnic perfusion which might inhibit the impending intestinal ischemia. Chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ) is the most probable place that is affected by dehydration.[12] Yogendran et al.,[13] who administered I.V. fluids before the induction of anaesthesia were unable to show a significant difference in the early post-operative period but reported a decrease in incidence of late PONV. Ali et al.,[14] have reported that a supplemental preoperative I.V. fluid therapy with 15 ml.kg-1 significantly reduced the incidence of PONV. Magner et al.,[6] reported that the administration of a crystalloid solution of 30 ml.kg-1 to healthy women undergoing ambulatory gynaecologic laparoscopy reduced the incidence of PONV. Holter et al.,[15] suggested that the intraoperative administration of 40 ml.kg-1 of fluid reduced the incidence of PONV. In all of the above studies, supplemental fluid volume, whether it was administrated intraoperatively or before the induction of anesthesia, was large. Although, the effect of fluid management in maintaining cardiovascular stability and renal function in major surgery has been studied, their place in minor surgery still remains to be established. Perioperative administration of large volumes may have significant adverse effects, especially in the patients who have cardiovascular, renal, hepatic, lung, or cerebral disorders. For this reason, only ASA I and ASA II patients were selected for the clinical investigation in the present study. Papadimitriou et al.[16] and Habib et al.,[17] suggested that the combination of the anti-emetics were superior, which is probably explained by the fact that the two drugs have different sites of action, thus preventing emesis by blocking different pathways. Adanir et al.,[18] reported that PONV can be further decreased by means of compensation of fluid losses of patients 2 h prior to the operation rather than by the compensation of fluid losses during the operation. Their argument is explained by the fact that if the fluid deficit is covered 2 h prior to the operation, the crystalloid fluids diffuse outside of the blood vessels into tissues and this allows the fluid to restore the deficit at the cellular level which may affect both the peripheral (mucosal hypoperfusion of gastrointestinal tract) and central (probably the hydration of CTZ cells) mechanisms of PONV. Differences that exist between the present study and those of previous investigators may be due to heterogenous surgical approaches, demographic variability and different volumes of fluid administration. The difference in the incidence of PONV in males and females has been attributed to fluctuations in female sex hormones.[19] Beattie et al.,[7] reported how a hormone-related threshold for PONV is altered by general anesthesia and mensuration has been reported as an important independent risk factor in PONV. In the present study, a higher incidence of nausea and vomiting were reported by the patients in menstrual phase of cycle, and required rescue anti-emetics according to the protocol. The role of supplemental oxygen, both intraoperatively and post-operatively, in decreasing incidence of PONV has been emphasized time and again in various studies.[20] To avoid the confounding effect of supplemental oxygen on the results of the study all patients were given 30/70 ratio of O2/N2O through surgery and 4L.min-1 by mask for 2 h post-operatively. As there was no significant difference in the hemodynamic parameters of the two groups, hypotension and hypercarbia were excluded as causative factors of PONV.[21] Furthermore, tissue oxygenation, mucosal perfusion and emetogenic mediator released were not measured, thus the mechanism of attenuation of PONV by I.V. fluid still remains speculative.

CONCLUSION

Modern multivariable studies, meta-analysis and systemic reviews have greatly increased our knowledge about the risk factors of PONV. Consensus is emerging that antiemetic prophylaxis is neither cost effective nor free from side effects. Multimodal management of PONV obviates the need of antiemetic prophylaxis and its associated side effects and therefore the importance of adequate hydration of patients has been stressed on. Our study reported statistically significant difference in the outcome of PONV in the two groups and it clearly elucidates that there was a reduced incidence of PONV and anti-emetic usage in the group receiving 30 ml.kg-1 CSL. We also found a positive correlation between PONV and women in the menstruating phase. To summarize, intravenous hydration is a safe and effective means of preventing PONV and ensuring patient satisfaction at the time of discharge.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Pubmed articles, National Medical Library (AIIMS)

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Watcha MF, White PF. Postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesthesiology. 1992;77:162–84. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199207000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gan TJ, Meyer T, Apfel CC, Chung F, Davis PJ, Eubanks S, et al. Consensus guidelines for managing PONV. Anaesth Analg. 2003;97:62–71. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000068580.00245.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Macario A, Weigner M, Carney S, Kim A. Which clinical anaesthesia outcomes are important to avoid? The perspective of patients. Anaesth Analg. 1999;89:652–8. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199909000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gold BS, Kitz DS, Lecky JH, Nerihaus JM. Unanticipated admission to the hospital following ambulatory surgery. JAMA. 1989;262:3008–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hofer CK, Zollinger A, Büchi S, Klaghofer R, Serafino D, Bühlmann S, et al. Patient well-being after general anaesthesia: A prospective, randomized, controlled multi-centre trial comparing intravenous and inhalation anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2003;91:631–6. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeg243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Magner JJ, McCaul C, Carton E, Gardiner J, Buggy D. Effect of intraoperative intravenous crystalloid infusion on postoperative nausea and vomiting after gynaecological laparoscopy: Comparison of 30 and 10 ml kg-1. Br J Anaesth. 2004;93:381–5. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeh219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beattie WS, Lindbland T, Buckley DN, Forrest JB. The incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting in women undergoing laparoscopy is influenced by day of menstrual cycle. Can J Anaesth. 1991;38:298–302. doi: 10.1007/BF03007618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fombeur PO, Tilleul PR, Beaussier MJ, Lorente C, Yazid L, Lienhart AH. Cost-effectiveness of propofol anesthesia using target-controlled infusion compared with a standard regimen using desflurane. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2002;59:1344–50. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/59.14.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martson A. Responses of the splanchnic circulation to ischaemia. J Clin Pathol Suppl (R Coll Pathol) 1977;11:59–67. doi: 10.1136/jcp.s3-11.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ljungquist O, Søreide E. Preoperative fasting. Br J Surg. 2003;90:400–6. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gan TJ, Soppitt A, Maroof M, el-Moalem H, Robertson KM, Moretti E, et al. Goal directed intra operative fluid administration reduces the length of hospital stay after major surgery. Anaesthesiology. 2002;97:820–6. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200210000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hornby PJ. Central neurocircuitry associated with emesis. Am J Med. 2001;111(Suppl 8A):106S–12. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00849-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yogendran S, Asokumar B, Cheng DC, Chung F. A prospective, randomized, double-blinded study of the effect of intravenous fluid therapy on adverse outcomes on outpatient surgery. Anesth Analg. 1995;80:686–696. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199504000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ali SZ, Taguchi A, Holtmann B, Kurz A. Effect of supplemental preoperative fluid on postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anaesthesia. 2003;58:775–803. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2003.03262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holter K, Klarskov B, Christensen DS, Lund C, Nielsen KG, Bie P, et al. Liberal versus restrictive fluid administration to improve recovery after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A randomized, double-blind study. Ann Surg. 2004;240:892–9. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000143269.96649.3b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Papadimitriou L, Livanios S, Katsaros G, Hassiakos D, Koussi T, Demesticha T. Prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting after laparoscopic gynecological surgery. Combined antiemetic treatment with tropisetron and metoclopramide versus metoclopramide alone. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2001;18:615–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2346.2001.00894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Habib AS, White WD, Eubanks S, Pappas TN, Gan TJ. A randomized comparison of a multimodal management strategy versus combination antiemetics for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2004;99:77–81. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000120161.30788.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adanir T, Aksun M, Ozgurbuz U, Altin F, Sencan A. Does preoperative hydration affect postoperative nausea and vomiting? A randomized, controlled trial. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2008;18:1–4. doi: 10.1089/lap.2007.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harmon D, O’Connor P, Gleasa O, Gardiner J. Menstrual cycle and the incidence of nausea and vomiting after laparoscopy. Anaesthesia. 2000;55:1164–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2000.01719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grief R, Laciny S, Rapf B, Hickle RS, Sessler DI. Supplemental Oxygen reduces the incidence of PONV. Anaesthesiology. 1999;91:1246–52. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199911000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pusch F, Berger A, Wildling E, Tiefenthaler W, Krafft P. The effects of systolic arterial blood pressure variations on postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2002;94:1652–5. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200206000-00054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]