Abstract

Background:

Limited evidence supports the efficacy of peripheral route fentanyl and local anesthetic combination for postoperative analgesia. Our study was therefore designed to demonstrate the analgesic efficacy of two different doses of fentanyl in combination with bupivacaine for surgical site infiltration in patients undergoing modified radical mastoidectomy (MRM).

Materials and Methods:

60 patients undergoing MRM under general anesthesia were randomly allocated into two groups, first group receiving 0.5% bupivacaine at a dose of 2 mg/kg body weight with 50 μg fentanyl and second group receiving bupivacaine 0.5% at a dose of 2 mg/kg body weight with 100 μg fentanyl as infiltration of operative field in and around the incision site, after the incision and just before completion of surgery. In postoperative period pain, nausea-vomiting and sedation was recorded at 0 hr, 2, 4, 6, 12 and 24 hrs.

Results:

Both the combinations of bupivacaine and fentanyl (Group I and Group II) were effective for postoperative analgesia. In both the groups the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) score was less than 3 at each time interval. None of the patients required rescue analgesia. The comparison of VAS scores at different intervals showed that group II had lower VAS scores at all time points.

Conclusions:

Fentanyl and bupivacaine combinations in doses of 50 and 100 μg along with 0.5% bupivacaine at a fixed dose of 2 mg/kg body weight are effective in the management of postoperative pain. Patients who received 100 μg fentanyl (Group II) had lower VAS scores as compared to the patients who received 50 μg fentanyl (Group I) with similar side effects.

Keywords: Bupivacaine, fentanyl, modified radical mastoidectomy, postoperative analgesia

INTRODUCTION

Post operative pain is still an unresolved problem, despite numerous developments in the field of pain management. It has been well understood that the most successful approach to manage post operative pain is multimodal. Post operative pain is mediated by nociceptive receptors which has a higher threshold than sensory receptors.[1] Nociceptors are found in the skin, muscles, ligaments, joints, organ capsules and vessel walls.[2] Pain is mediated through Ad (myelinated) and C (non myelinated) fibers.[3] Stimulation of Ad fibers results in localized précised pain whereas stimulation of C fibers causes a dull and burning pain.[4] Visceral pain is sensed by mechanical type of receptors and chemoceptors and pain originating from viscera is of diffuse and dull in nature.[5,6] Major part of post operative pain originates from nociceptors in the cutis and subcutis.[6,7,8]

Recent studies have demonstrated the analgesic efficacy of opioids and local anesthetics either alone or in combination.[9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19] The present study was conducted to demonstrate whether the combination of local anesthetic (Bupivacaine) and opioid (Fentanyl) has any analgesic effect before and after subcutaneous infiltration in modified radical mastoidectomy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Trial design and procedures

After getting clearance from the institutional ethics committe, this prospective, double blind, and parallel group randomized study was performed on 60 ASA grade I and II patients admitted to our institution undergoing elective modified radical mastoidectomy (MRM) under general anesthesia. Following detailed pre-anesthetic checkup, written informed consent was taken from all patients. Only patients who were willing, 16-60 years of either sex or ASA grade I and II were included. Exclusion criteria were patients with age less than 16 and more than 60 years, drug or alcohol addicts, obese (patient with body weight more than 20% of ideal body weight), patient with history of drug allergy to fentanyl or amide group local anesthetics, patients using NSAIDS, opioids or any other analgesic, confirmed local anesthetic toxicity, history of malignancy chronic pain syndrome where pain evaluation judged is unreliable because of neurological disease or treatment with steroid prior to surgery and deranged coagulation or bleeding parameters and with cardiovascular, pulmonary and neurological disorder.

Patients were randomly allocated by computer generated random tables to one of two groups comprising 30 patients each. Sixty opaque envelopes containing the code numbers for group I and group II were prepared and sealed, which were opened in the operation theatre only. Patients recruited and randomized who did not receive the study drug because of a change in surgical plan were withdrawn and their randomization number reallocated.

Group I: (bupivacaine + fentanyl 50 μg) – patients received a combination of 0.5% bupivacaine at a dose of 2 mg/kg body weight and 50 μg (1 ml) fentanyl.

Group II: (group bupi + fent 100) – patients received a combination of 0.5% bupivacaine at a dose of 2 mg/kg body weight and 100 μg (2 ml) fentanyl.

The drug solution was prepared by a doctor who had not participated in the study and was not aware of the study protocol. Surgeon and the anesthesiologist were unaware of the drug solution to which each patient was randomized. The half study drug solution was given just after incision and half at the end of surgery before wound closure, the study drug solution was infiltrated subcutaneously as well as, in and all around the incision line.

Anesthetic technique

In the operation theatre, after establishing an intravenous route, ringer lactate solution was started. All patients received intravenous injection midazolam 0.03 mg/kg and tramadol 2 mg/kg 10 minutes before induction of anesthesia and after every 30 minutes of induction tramadol 1 mg/kg was repeated. Standard monitors were attached like heart rate, blood pressure, ECG and pulse oximetry.

After tracheal intubation, end tidal carbondioxide monitoring was initiated. Anesthetic technique was standardized. All patients were preoxygenated for three minutes. Anesthesia was induced with oxygen, nitrous oxide, and propofol 2 mg/kg. succinylcholine 1.5 mg/kg was used to facilitate tracheal intubation. Anesthesia was maintained with nitrous oxide 66%, oxygen 33% and halothane 0.5% and vecuronium. Neuromuscular block was reversed with neostigmine 0.05 mg/kg and atropine 0.02 mg/kg. All the operations were performed by a single team of surgeons by standard technique. In both the groups, postoperative analgesia was standardized. Injection diclofenac 1 mg/kg was started eight hourly in postoperative ward as per routine analgesic protocol being followed in our institution by surgeons starting from the time when patient has arrived in postsurgical ward from operation theatre. In both the groups’ presence of pain, nausea and sedation was assessed at 0 hour (time at arousal from anesthesia), 2, 4, 6, 12 and 24 hrs after completion of surgery.

Time to first analgesic requirement, total analgesic consumption in the first 24 hours postoperatively and occurrence of adverse events (e.g., Tinnitus, circumoral numbness, twitching, pruritis, respiratory depression) were also recorded. All postoperative observations were performed by investigators and nursing staff, who were anaware of study group allocation.

Pain assessment

Eleven point Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) score (0 = no pain and 10 = worst possible pain), at rest on pressure on incision site was used to assess pain at rest, at above intervals. At any point of time if VAS was >3, injection tramadol 1 mg/kg body weight 8 hrly was planned to be added. if patient had VAS > 3 even 30 minutes after receiving tramadol then fentanyl 2 μg/kg bolus was planned to be given intravenously.

Nausea and vomiting was assessed on a three point score:

-

0.

No nausea/vomiting in past time interval and

-

1.

Nausea in the past interval,

-

2.

Vomiting in the past interval.

Nausea lasting for more than 10 mins and vomiting was planned to be treated with parentral ondensetron 0.1 mg/kg body weight.

Sedation was assessed on a score of 0 to 2:

-

0.

Awake and alert patient,

-

1.

A quietly awake patient and

-

2.

Asleep but easily arousable patient.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using a standard statistical program. Demographic data were analyzed using Student's t-test. Repeated measurements (pain scores, nausea and vomiting scores and sedation scores) were found to be none normally distributed. Comparisons between groups at each time point was made by nonparametric Mann Whitney test and within groups by Wilcoxon signed rank sum test. The P < 0.05 was set as statistically significant.

RESULTS

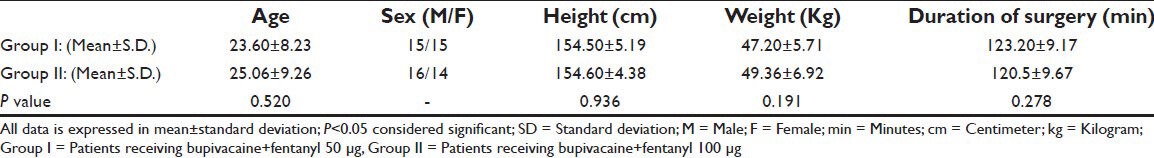

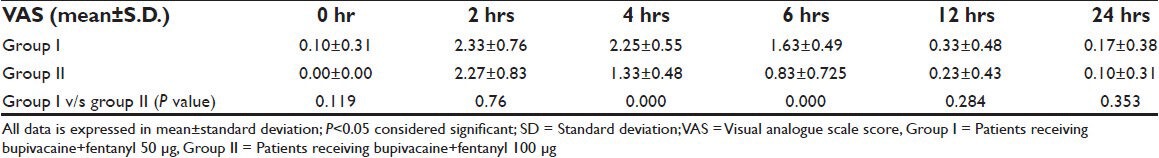

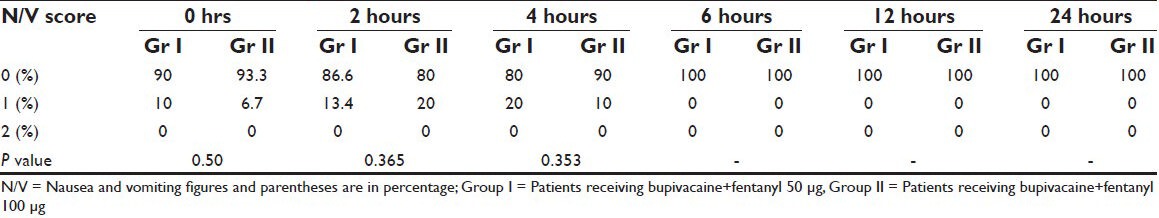

Sixty patients were taken up for the study, thirty in group I (bupivacaine + fentanyl 50 μg) and thirty in group II (bupivacaine + fent 100 μg) were randomized to receive a combination of bupivacaine and fentanyl for wound infiltration in and around the incision site. All the patients were included in the statistical analysis. Groups were comparable in terms of age, sex, weight, height and duration of surgery [Table 1]. In both groups VAS was less than three at each time interval [Table 2]. None of the patients in either group required rescue analgesia. The comparison of visual analogue scale (VAS) scores at different time intervals showed that group II had lower VAS score than group I at all time intervals. The incidence of nausea was found to be statistically significantly lower in group I at 2 hours and comparable at all other time intervals [Table 3]. There was no sedation, pruritis and symptoms suggestive of local anesthetic toxicity in patients of either group at any time interval and the two groups were comparable.

Table 1.

Age sex, height and weight characteristics of patients in two groups

Table 2.

Visual analogue scores in two groups at different time intervals

Table 3.

Nausea and vomiting scores in the two groups at different time intervals

DISCUSSION

It has been noted that patients who received fentanyl intravenously has reduced wound hyperalgesia 24 to 48 hours post operatively, this effect was explained by the central action of fentanyl.[9] However, the action of fentanyl on nociceptors in and around the wound area can produce an antinociceptive effect of fentanyl by interacting with peripheral opioid receptors.[10,11,12,13] It is also understood that it stays in the muscle and fat compartments for many hours (>23 hrs) after a single intravenous injection.[14] Therefore, reduction in wound hyperalgesia has a peripheral underlying mechanism. Bupivacaine is one of the longest acting local anesthetic agents with the effect lasting for up to 16 hrs. It is four times more potent than lignocaine. Its effect is due to binding with the nerve tissues. In our study fentanyl 50 and 100 μg was used in combination with bupivacaine 2 mg/kg for infiltration in and around the incision site. It was observed that VAS score in both the groups was <3 at all times and no patient in either group required rescue analgesia. The comparison of VAS scores at different intervals showed that group two had better analgesia. Our study demonstrated that the combination of bupivacaine and fantanyl for operative field infiltration was associated with better postoperative analgesia [Table 2].

In our study, fentanyl was applied in combination with a local anesthetic. Likar et al. demonstrated that morphine added to a local anesthetic for submucosal infiltration in dental surgery resulted in an improvement of postoperative analgesia for 24 hrs similar to our results.[15] The analgesic effect of additional opioid was also demonstrated in several studies.[15,16,17] Fentanyl with its less histamine releasing property and a stronger μ-receptor agonist activity may be a better drug than morphine or meperidine for peripheral analgesia. Evidence has shown that fentanyl may have dual mechanism of action.[18,20] Being an opioid of phenolpiperidine group it could have local anesthetic effect on the nerves. A dose of 10 μg fentanyl used by Tverskoy et al. failed to reduce the analgesic consumption in patients given fentanyl- lignocaine combination for wound infiltration.[17] A dose of 25 μg fentanyl with lignocane utilized by PT Vijay kumar et al., enhanced the duration of analgesia.[16] Fentanyl used at a dose of 100 μg by Gupta et al. for peripheral analgesia in laparoscopic surgery for intraperitonial instillation, showed better analgesia without any complications and toxicity.[19] Therefore the doses of 50 μg and 100 μg fentanyl were chosen in our study along with bupivacaine, a longer acting local anesthetic. In both the groups, we did not observe any complications (respiratory depression, pruritis, sedation) and signs of toxicity of fentanyl or bupivacaine clinically, though we have not measured the serum level of the drugs.

The fentanyl-induced enhancement of postoperative analgesia observed in our study is mediated by peripheral opioid receptors. A less likely alternative explanation is associated with the local anesthetic action of fentanyl (nonspecific action on sodium conductance). Since the report by Kosterlitz and Wallis local anesthetic properties of opioids have been discussed in may studies.[21,22] The local anesthetic effect of fentanyl has been described in vitro when very high concentrations of the drug were used.[20,23] However, in vivo, even high concentrations of fentanyl did not affect peripheral nerve compound action potentials.[24] In clinically relevant concentrations fentanyl also failed to affect the nerve conduction in isolated dorsal roots.[22] In conclusion, fentanyl added to a local anesthetic for wound infiltration can enhance postoperative analgesia via a peripheral mechanism. In this study, It is clear that the addition of opioids to local anesthetics for postoperative pain results from a truly peripheral rather than a central site of action. This is because peripheral uptake of opioids into the circulation (effect of systemic dose lasts for half an hour only) and transport to the CNS cannot be explained by the central action of fentanyl. It has been postulated that inflammatory hyperalgesia is especially amenable to peripheral antinociceptive.[25] The presence of inflammation has been found to enhance the efficacy of peripherally applied opioids.[12] This is because inflammation disrupts the perineurium as well as increases the number of peripheral sensory nerve terminals. The favorable results in our study and of other authours may be because of infiltration being performed after completion of surgery when inflammatory response may have begun.

Since wound infiltration with bupivacaine and its combination with fentanyl affects only somatic component of postoperative pain, it has always been used as a part of multimodal analgesia. Unfortunately NSAIDs alone are insufficient to effectively treat post-operative pain. However, inclusion of NSAIDs in a multimodal approach to pain relief after surgery has been very successful both in improving the quality of analgesia resulting from systemic or neuraxially administered opioids and reducing side effects.[26] In this study we used subcutaneous infiltration of bupivacaine and fentanyl in combination with diclofenac sodium in post-operative period so as to cover both somatic and visceral pain. Both the combinations of Bupivacaine and fantanyl are found to be efficacious as a part of multimodal analgesia. We used 50 μg and 100 μg fentanyl which is well with in the permissible limit and there was no evidence clinically that the dose of drug used had crossed the toxic levels.

CONCLUSIONS

Fentanyl and bupivacaine combinations in doses of 50 and 100 μg along with 0.5% bupivacaine at a dose of 2 mg/kg body weight are effective in the management of postoperative pain, as a part of multimodal analgesic regimen. Patients who received 100 μg fentanyl (Group II) had lower VAS scores as compared to the patients who received 50 μg fentanyl (Group I) though this was not statistically significant at all times. This method of analgesia is a safe, easy and effective that targets pain at its origin and is virtually free from side effects.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burgess P, Perl E. Handbook of sensory physiology. Heidelberg: Springer Verlag; 1973. Cutaneous mechanoreceptors and nociceptors; pp. 29–78. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raja S, Meyer R, Campbell J. Peripheral mechanism of somatic pain. Anesthesiology. 1998;68:571–90. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198804000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yaksh TL, Hammond DL. Periferial and central substences involved in the rostrad transmission of nociceptive information. Pain. 1982;13:1–85. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(82)90067-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collins WF, Nulsen FE, Randt CT. Relation of peripheral fibre size and sensation in man. Arch Neurol. 1960;3:381–5. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1960.00450040031003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ness TJ, Gebhart GF. Visceral pain. A review of experimental studies. Pain. 1990;41:167–234. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(90)90021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McMahon S, Dimtrieva N, Koltzenburg M. Visceral pain. Br J Anaesth. 1995;75:132–44. doi: 10.1093/bja/75.2.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scott N, Mogensen T, Greulich A, Hjortso N, Kehelt H. No effect of continous i.p. infusion of bupivacaine on postoperative analgesia, pulmonary function and the stress response to surgery. Br J Anaesth. 1988;61:165–8. doi: 10.1093/bja/61.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wallin G, Cassuto J, Hogstrom S, Hedner T. Influence of intraperitoneal anesthesia on pain and the sympathoadrenal response to abdominal surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1988;32:553–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1988.tb02785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tverskoy M, Oz Y, Isakson A, Finger J, Bradley EL, Kissin L. Preemptive effect of fentanyl and ketamine on postoperative pain and wound hyperalgesia. Anesth Analg. 1994;78:205–9. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199402000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferriera SH, Nakamura M. Prostaglandin hyperalgesia. The peripheral analagesic activity of morphine enkephalin and opioid antagonists. Prostaglandins. 1979;18:191–8. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(79)90104-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joris J, Dubner R, Hargreaves K. Opioid analgesia at peripheral site. A target for opioids released during stress and inflammation? Anesth Analg. 1987;84:225–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stein C, Millan MJ, Shippenberg TS, Herz A. Peripheral effects of fentanyl upon nociception in inflamed tissue of the rat. Neurosci Lett. 1988;84:225–8. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(88)90412-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stein C. The control of peripheral tissue by opioids. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1685–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199506223322506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bjorkman S, Stanski MD, Verotta D, Hsrashiman H. Comparative tissue concentration profiles of fentanyl and alfentani in humans predicted from tissue/blood partition data obtained in rats. Anesthesiology. 1990;72:865–73. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199005000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Likar R, Stittl R, Gragger K, Pipam W, Blatnig H, Breschan C, et al. Peripheral morphine analgesia in dental surgery. Pain. 1998;76:145–50. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(98)00036-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vijay Kumar PT, Bhardwaj N, Sharma K, Batra YK. Peripheral analgesic effect of wound infilitration with lignocaine, fentanyl and comflination of lignocaine-fentanyal on post opretive pain. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2006;22(suppl 2):161–7. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tverskoy M, Braslavsky A, Mazor A, Ferman K, Kissin I. The peripheral effect of fentanyl on post operative pain. Anesth Analg. 1998;87:1121–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dodson BA, Miller KW. Evidence for a dual mechanism in the anesthetic action of opioid peptid. Anesthesiology. 1985;62:615–20. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198505000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gupta R, Bogra J, Kothari N, Kohli M. Postoperative analgesia with intraperitoneal fentanyl bupivacaine. A randomized control trial. Can J Med. 2010;1(suppl 1):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gissen AJ, Gugino LD, Datta S, Miller J, Covino BG. Effects of fentanyl and sufentanil on peripheral mammalin nerves. Anesth Analg. 1987;66:1272–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kosterlitz HW, Wallis DL. The action of morphine-like drugs on impulse transmission in mammalian nerve fibers. Br J Pharmacol. 1964;22:449–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1964.tb01704.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jaffe RA, Rowe MA. A comparison of the local anesthetic effect of meperidine, fentanyl, and sufentanil on dorsal root axons. Anesth Analg. 1996;83:776–81. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199610000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Power I, Browen DT, Wildsmith JA. The effect of Fentanayl, meperidine and diamorphine on nerve conduction in vitro. Reg Anesth. 1991;16:204–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yuge O, Mastssumoto M, Kitahata LM, Collins JG, Senami M. Direct opioid application to peripheral nerves does not alter compound action potential. Anesth Analg. 1985;64:667–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lyons B, Lohan D, Flym C, Mc Carroll M. Modification of pain on injection of propofol. A comparision of pethdine and lignocaine. Anaesthesia. 1996;51:394–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1996.tb07756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pan PH. Post caesarean analgesia delivery pain management: Multimodal approach. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2006;15:185–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]