Abstract

This study was designed to evaluate the effect of adding dexmedetomidine to regular mixture of epidural drugs for pregnant women undergoing elective cesarean section with special emphasis on their sedative properties, ability to improve quality of intraoperative, postoperative analgesia, and neonatal outcome.

Materials and Methods:

Fifty women of ASA physical status I or II at term pregnancy were enrolled randomly to receive plain bupivacaine plus fentanyl (BF Group) or plain bupivacaine plus mixture of fentanyl and dexmedetomidine (DBF Group). Incidence of hypotension, bradycardia, Apgar scores, intraoperative pain assessment, onset of postoperative pain, sedation scores, and side effects were recorded.

Results:

No difference in the times taken for block to reach T4 sensory level, to reach the highest level of sensory block, and interval between first neuraxial injection and onset of surgery between the groups was noted. Onset of postoperative pain was significantly delayed in the DBF group (P = 0.001), the need for supplementary fentanyl was significantly less in DBF group (P = 0.03), no significant difference was noted between both groups regarding neonatal Apgar scores as well as the incidence of hypotension, bradycardia, nausea, vomiting, and duration of motor blockade. DBF group had significantly less incidence of shivering (P = 0.03).

Conclusion:

Adding dexmedetomidine to regular mixture of epidural anesthetics in women undergoing elective cesarean section improved intraoperative conditions and quality of postoperative analgesia without maternal or neonatal significant side effects.

Keywords: Combined spinal-epidural anesthesia, elective caesarean section, epidural dexmedetomidine

INTRODUCTION

Regional anesthesia is preferred for cesarean section as it allows a parturient to remain awake and participate in the birth of her baby while avoiding the risks of general anesthesia.[1] The combined spinal-epidural (CSE) technique is frequently used to provide anesthesia and analgesia for labor and delivery.[2] To improve the quality of intraoperative anesthesia, postoperative analgesia and aid early ambulation and recovery of motor block, several agents have been employed such as opioids and α-2 adrenergic agonist. Some recent placebo-controlled studies suggested that α-2 adrenergic agonist have both analgesic and sedative properties when used as an adjuvant in regional anesthesia.[3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]

Dexmedetomidine is a highly selective α-2 adrenergic agonist with an affinity eight times greater than that of clonidine. The dose equivalence of these drugs had not been studied before, but the observations of various studies have stated that the dose of clonidine is 1.5-2 times higher than that of dexmedetomidine when used in epidural route.[12,13,14,15,16,17] The anesthetic and the analgesic requirement get reduced by the use of these two adjuvants because of their analgesic properties and augmentation of local anesthetic effects as they cause hyperpolarization of nerve tissues by altering transmembrane potential and ion conductance at locus coeruleus in the brainstem.[18,19,20,21,22] The stable hemodynamics and the decreased oxygen demand due to enhanced sympatho-adrenal stability make them very useful pharmacologic agents.[23,24]

The safety of the use of dexmedetomidine on neonatal outcome is a very important issue. Experimental study on acute exposure of rats to dexmedetomidine at the anticipated delivery time recorded absence of any adverse effects on perinatal morphology of pups, their birth weight, crown-rump length, physical growth, and postnatal behavioral performances and concluded that dexmedetomidine did not affect those parameters.[25]

Others studied the transfer of clonidine and dexmedetomidine across the isolated perfused human placenta and concluded that dexmedetomidine disappeared faster than clonidine from the maternal circulation, while even less dexmedetomidine was transported into the fetal circulation.[26]

Some case reports concluded that dexmedetomidine has no harmful effects during cesarean delivery.[27,28,29]

Our hypothesis was that the addition of dexmedetomidine to epidural bupivacaine and fentanyl could improve intraoperative anesthesia and postoperative analgesia in women undergoing elective cesarean section using a CSE technique without significant neonatal side effects.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After approval by local research ethics committee, informed consent was obtained from all patients participating in the study. Healthy (ASA I, II), 21-41-year-old women at term were randomly allocated into two groups equally. Computer-generated simple random sampling procedure was used to allocate the subjects. Both nulliparous and multiparous women were included. All women were scheduled for elective cesarean section. Exclusions criteria were twin pregnancy, placenta praevia, opioid agonist or agonist/antagonist administration in the preceding 6 h (or within 1 h if given intravenously), obesity (BMI > 38 kg/m2), extremes of height (<140 or >180 cm), active labor, history of bleeding diathesis, history or presence of cardiac, respiratory, hepatic, and/or renal failures or those who had contraindications to neuraxial block.

The study drugs were prepared in unlabeled syringes by anesthesia technician not involved in the study who used the randomization protocol to assign participants to their respective groups. Patients were premedicated with oral ranitidine 150 mg the night before and on the morning of surgery. The second dose was given with oral metoclopramide 10 mg. In the operation theatre, a good intravenous access was secured and monitoring devices were attached such as electrocardiograph (ECG), pulse oximetry (SpO2), non-invasive blood pressure (NIBP), and respiratory rate. Baseline parameters were recorded. A fluid preload of 500 mL of lactated Ringer's solution was given and baseline blood pressure and heart rate were recorded in the right-wedged supine position. Oxygen at 6 L/min was administered via Hudson face mask.

In the sitting position, CSE anesthesia was performed using a needle-through-needle technique. The epidural space was located using loss of resistance to air with an 18-gauge Tuohy needle. The dural puncture at L3-4 level was achieved with 27-gauge pencil-point needle. After confirmatory aspiration of cerebrospinal fluid, 2 mL of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine was injected intrathecally. The spinal needle was withdrawn and a 20-gauge epidural catheter inserted 3-4 cm into the epidural space. The catheter was secured and the patient was placed in the supine position with left uterine displacement. All then received 20 mL of study solution via the epidural catheter either as 10 mL 0.25% plain bupivacaine plus fentanyl 100 μg in 10 mL 0.9% sodium chloride (BF Group) or 10 mL 0.25% plain bupivacaine plus mixture of fentanyl 100 μg and dexmedetomidine 1 μg/kg in 10 mL 0.9% sodium chloride (DBF Group). Hypotension, defined as 20% fall in blood pressure from pre-induction levels or a systolic blood pressure lower than 100 mmHg, was treated immediately by intravenous injection of 5 mg ephedrine. The level of sensory block was assessed at 2-min intervals for 30 min after epidural injection using pinprick. The highest level of sensory block (S max) and time taken to reach S max were recorded. Motor block of the lower extremities was assessed at 5-min intervals for 30 min using the modified Bromage score (BS): BS0; full flexion of hip, knee, and ankle. BS1; impaired hip flexion. BS2; impaired hip and knee flexion. BS3; unable to flex hip, knee, or ankle. Complete motor block was defined as BS3. Time intervals from intrathecal injection to readiness for surgery, skin incision to delivery and uterine incision to delivery were recorded. Surgery was performed by one of two consultant surgeons of similar clinical experience; they were blinded to the allocation group. Intraoperative and postoperative pain were assessed by 10-point Verbal Rating Scale (VRS), in which 0 represented no pain and 10 represented worst possible pain. VRS was measured every 15 min intraoperative and every 4 h postoperatively by an anesthesiologist who was unaware of the patient allocation group. If women complained of pain (defined as VRS > 4), intravenous fentanyl was given in 50 μg increments. The requirement for supplementary analgesia was noted in different groups.

Sedation scores were recorded using 5-point scale (1 = completely awake, 2 = awake but drowsy, 3 = asleep but responsive to verbal commands, 4 = asleep but responsive to tactile stimulus, 5 = asleep and not responsive to any stimulus),[30] just before the initiation of surgery and thereafter every 15 min during the surgical procedure. Adverse effects such as hypotension, nausea, vomiting, and shivering were also recorded. All neonates were evaluated by a pediatrician who was unaware of group assignment. Apgar scores at 1 and 5 min and umbilical cord pH were recorded. The need for neonatal oxygen therapy was noted. Breast feeding was prohibited for the first 24 h after cesarean delivery. Following surgery, patients were nursed in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU). Recovery from motor block was defined as the time from injection of epidural solution to BS0. The onset of postoperative pain defined as the time from completion of surgery to onset of VAS > 4 were recorded.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SD or frequency and percentages as appropriate. Unpaired Student t tests were used to see statistical significance difference for interval variables and Chi-square tests or Fisher exact tests were performed for categorical variables between the groups. P value of 0.05 (two-tailed) was considered as statistically significant. SPSS 19.0 Statistical Package was used for the analysis.

RESULTS

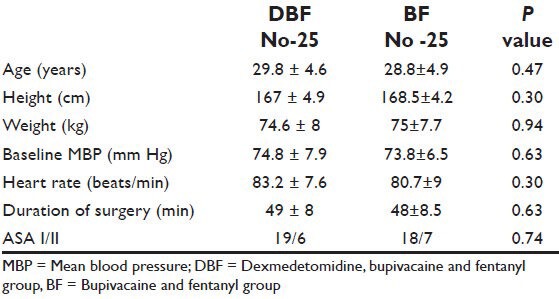

The demographic profiles of the patients in both the groups were comparable with regards to age, weight, and height. The distribution as per ASA status was similar in both the groups and mean duration of surgery was comparable in both the groups (P = 0.74) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Patients demographic and clinical characteristics

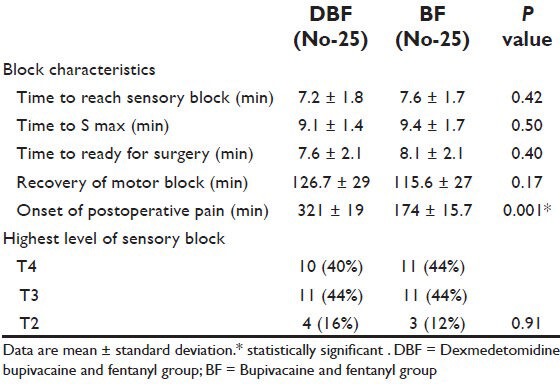

Table 2 showed that the time needed for the block to reach T4, highest level of sensory block (S max), time interval between anesthesia and onset of surgery and recovery from motor blockade were not significant statistically. The onset of postoperative pain was significantly delayed in the DBF Group (P = 0.001).

Table 2.

Block characteristics

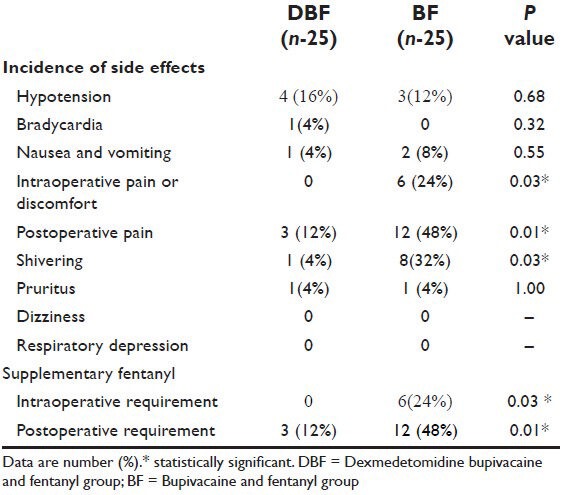

In DBF Group, all women did not need any supplementary analgesic throughout the operation, while, in the DF group, 6 patients needed supplementary fentanyl (P = 0.03) for complaining intraoperative pain or discomfort (defined as VRS > 4).

The postoperative analgesic requirement was significantly reduced in DBF group as compared to DF group (P = 0.01). Shivering was also significantly reduced in DBF group as compared to DF group (P = 0.03). Incidence of hypotension, bradycardia, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, and pruritus were not significant between the groups [Table 3]. There were also no significant differences in neonatal outcomes in both groups.

Table 3.

Incidence of side effects

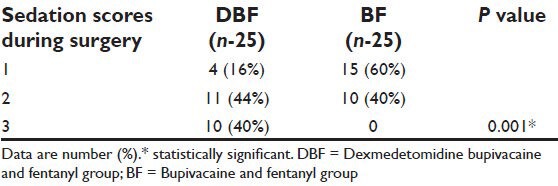

Sedation scores were significantly higher in DBF group (P = 0.001) [Table 4].

Table 4.

Comparison of intra-operative sedation scores in patients of group DBF and group BF

DISCUSSION

Our study emphasized that the addition of dexmedetomidine 1 μg/kg to a standardized CSE dosage regimen (bupivacaine and fentanyl) achieved better intraoperative conditions and improved analgesia and provided good sedation level, prolonged postoperative analgesia, and lower incidence of shivering than those who received only bupivacaine and fentanyl.

Epidural dexmedetomidine in dose of 1 μg/kg did not cause significant hemodynamic effects and did not affect neonatal outcome. Dexmedetomidine as adjuvant to bupivacaine and fentanyl achieved better sedation, as 40% of the patients had sedation in score 3 and were arousable by gentle tactile stimulation as compared to no patients in BF group. About 60% of the patients remained awake but calm in the BF group as compared to 16% in the DBF group, who were equally cooperative and calm. Overall sedation scores were statistically more in dexmedetomidine group (DBF group).

Our data support previous studies that used dexmedetomidine as additive to regional anesthetics; Salgado et al., in a double-blind study conducted in 40 patients undergoing hernia repair or varicose vein surgery concluded that adding dexmedetomidine 1 μg/kg to epidural ropivacaine increases sensory and motor block duration and prolongs postoperative analgesia without causing hemodynamic instability.[11]

Bajwa et al., compared dexmedetomidine 1.5 μg/kg versus clonidine 2 μg/kg as an additive to epidural ropivacaine in patients scheduled for vaginal hysterectomy. They observed that dexmedetomidine is a better adjuvant than clonidine in terms of intraoperative and postoperative analgesia, patient's satisfaction, and cardiorespiratory effects.[31]

El-Hennawy et al., compared dexmedetomidine versus clonidine as additive to caudal bupivacaine in children aged 6 months to 6 years undergoing lower abdominal surgeries and concluded that both drugs significantly improves postoperative analgesia.[10]

Antishivering mechanism of dexmedetomidine had been studied, although not extensively. In the present study, we obtained satisfactory results in the prevention of shivering in patients who were administered with dexmedetomidine, as only 1 patient out of a total of 25 suffered an episode of shivering. The α-2 receptor agonists are known to prevent shivering to a moderate extent without any associated respiratory depression as with other antishivering drugs like meperidine, dexmedetomidine reduces shivering by lowering vasoconstriction and shivering thresholds.[32]

Kanazi et al., investigated the effect of adding a small dose of 3 μg of intrathecal dexmedetomidine to 12 mg bupivacaine and found a significant prolongation of sensory and motor block as compared to bupivacaine alone.[33] In dissimilarity to our study, we failed to demonstrate a statistically significant change in sensory and motor block time.

On the other hand, Konaki et al., demonstrated that 10 μg of dexmedetomidine HCl produces moderate to severe demyelination of spinal cord white matter in rabbits following epidural administration. They postulate that low pH of 4.5-7.0 of dexmedetomidine is responsible for injury to the myelin sheath.[34] However, clonidine with similar pH (5-7) does not exert neurotoxic side effects.[35,36,37]

To our knowledge, there are no previous study on using dexmedetomidine during cesarean section had not been addressed apart from only individual case reports; Neumann et al., used dexmedetomidine to facilitate awake fiberoptic endotracheal intubation for patient with spinal muscular atrophy 10 min before cesarean delivery and found no serious neonatal effects were detected.[27] Similarly, Palanisamy et al., used intravenous dexmedetomidine successfully as an adjunct to opioid-based PCA and general anesthesia for cesarean delivery in a parturient with a tethered spinal cord, they achieved favorable maternal and neonatal outcome.[28] Also, others used intravenous dexmedetomidine infusion for labor analgesia in patient with pre-eclampsia without significant neonatal side effects.[29]

The limitations of this study were the relatively small number of patients included and lack of follow-up of patients until the time of discharge from hospital. The strengths of this study were performance of the surgical procedure by two consultants with the same experiences in a single center and postoperative data collected by a single blinded investigator.

CONCLUSION

Addition of dexmedetomidine 1 μg/kg to an epidural bupivacaine/fentanyl combination in patients undergoing elective cesarean section using the CSE technique improves the intraoperative conditions, provides good sedation level, and improves the quality of postoperative analgesia without significant maternal or neonatal side effects.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Carrie LE. Extradural, spinal or combined block for obstetric surgical anesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 1990;65:225–33. doi: 10.1093/bja/65.2.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buvanendran A, McCarthy RJ, Kroin JS, Leong W, Perry P, Tuman KJ. Intrathecal magnesium prolongs fentanyl analgesia: A prospective randomized controlled trial. Anesth Analg. 2002;95:661–6. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200209000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamibayashi T, Maze M. Clinical uses of alpha-2 adrenergic agonists. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:1345–9. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200011000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scafati A. Analgesia and alpha agonists 2. Medens Rev. 2004:4–7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mauro VA, Brandão ST. Clonidine and dexmedetomidine through epidural route for post-operative analgesia and sedation in a colecistectomy. Rev Bras Anestesiol. 2004;4:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gabriel JS, Gordin V. Alpha 2 agonists in regional anaesthesia and analgesia. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2001;14:751–3. doi: 10.1097/00001503-200112000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hall JE, Uhrich TD, Ebert TJ. Sedative, analgesic and cognitive effects of clonidine infusions in humans. Br J Anaesth. 2001;86:5–11. doi: 10.1093/bja/86.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hall JE, Uhrich TD, Barney JA, Arain SR, Ebert TJ. Sedative, amnestic, and analgesic properties of small-dose dexmedetomidine infusions. Anesth Analg. 2000;90:699–705. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200003000-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Mustafa MM, Abu-Halaweh SA, Aloweidi AS, Murshidi MM, Ammari BA, Awwad ZM. Effect of dexmedetomidine added to spinal bupivacaine for urological procedure. Saudi Med J. 2009;30:365–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El-Hennawy AM, Abd-Elwahab AM, Abd-Elmaksoud AM, El-Ozairy HS, Boulis SR. Addition of clonidine or dexmedetomidine to bupivacaine prolongs caudal analgesia in children. Br J Anaesth. 2009;103:268–74. doi: 10.1093/bja/aep159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salgado PF, Nascimento P, Módolo NS, Sabbag AT, Silva PC. Adding dexmedetomidine to ropivacaine 0.75% for epidural anesthesia. Does it improve the quality of the anesthesia? Anesthesiology. 2005;103:974A. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bucklin B, Eisenach JC, Tucker B. Pharmacokinetics and dynamic studies of intrathecal, epidural and intravenous dexmedetomidine. Anesthesiology. 1991;75:662. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bischoff P, Kochs E. Alpha2-agonists in anaesthesia and intensive medicine. Anaesthesiol Intensivmed Notfallmed Schmerzther. 1993;28:2–12. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-998867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Villela NR, Nascimento Pd., Junior Dexmedetomidine in anesthesiology. Rev Bras Anestesiol. 2003;53:97–113. doi: 10.1590/s0034-70942003000100013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Linde H e Mo. The clinical use of dexmedetomidine. Rev Bras Anestesiol. 2004;54:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schnaider TB, Vieira AM, Brandão AC, Lobo MV. Intra-operative analgesic effect of cetamine, clonidine and dexmedetomidine, administered through epidural route in surgery of the upper abdomen. Rev Bras Anestesiol. 2005;55:525–31. doi: 10.1590/s0034-70942005000500007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ebert TJ, Hall JE, Barney JA, Uhrich TD, Colinco MD. The effects of increasing plasma concentrations of dexmedetomidine in humans. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:382–94. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200008000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Milligan KR, Convery PN, Weir P, Quinn P, Connolly D. The efficacy and safety of epidural infusions of levobupivacaine with and without clonidine for postoperative pain relief in patients undergoing total hip replacement. Anesth Analg. 2000;91:393–7. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200008000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klimscha W, Chiari A, Krafft P, Plattner O, Taslimi R, Mayer N, et al. Hemodynamic and analgesic effects of clonidine added repetitively to continuous epidural and spinal blocks. Anesth Analg. 1995;80:322–7. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199502000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fukushima K, Nishimi Y, Mori K. The effect of epidural administered dexmedetomidine on central and peripheral nervous system in man. Anesth Analg. 1997;84:292S. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scheinin M, Pihlavisto M. Molecular pharmacology of alpha-2-adrenoceptor agonists. Baillière's Clin Anaesth. 2000;14:247–60. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Correa-Sales C, Rabin BC, Maze M. A hypnotic response to dexmedetomidine, an alpha-2 agonist, is mediated in the locus coeruleus in rats. Anesthesiology. 1992;76:948–52. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199206000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taittonen MT, Kirvelä OA, Aantaa R, Kanto JH. Effect of clonidine and dexmedetomidine premedication on perioperative oxygen consumption and haemodynamic state. Br J Anaesth. 1997;78:400–6. doi: 10.1093/bja/78.4.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buerkle H. Peripheral anti-nociceptive action of alpha-2-adrenoceptor agonists. Baillière's Clin Anaesth. 2000;14:411–8. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tariq M, Cerny V, Elfaki I, Khan HA. Effects of subchronic versus acute in utero exposure dexmedetomidine on foetal developments in rats. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008;103:180–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2008.00282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ala-Kokko TI, Pienimäki P, Lampela E, Hollmén AI, Pelkonen O, Vähäkangas K. Transfer of clonidine and dexmedetomidine across the isolated perfused human placenta. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1997;41:313–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1997.tb04685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neumann MM, Davio MB, Macknet MR, Applegate RL. Dexmedetomidine for awake fiberoptic intubation in a parturient with spinal muscular atrophy type III for cesarean delivery. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2009;18:403–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palanisamy A, Klickovich RJ, Ramsay M, Ouyang DW, Tsen LC. Intravenousdexmedetomidine as an adjunct for labor analgesia and cesarean delivery anesthesia in a parturient with a tethered spinal cord. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2009;18:258–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abu-Halaweh SA, Al Oweidi AK, Abu-Malooh H, Zabalawi M, Alkazaleh F, Abu-Ali H, et al. Intravenous dexmedetomidine infusion for labour analgesia in patient with preeclampsia. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2009;26:86–7. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0b000e000000f3fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Memis D, Turan A, Karamanlıoglu B, Pamukc Z, Kurt I. Adding dexmedetomidine to lidocaine for intravenous regional anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 2004;98:835–40. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000100680.77978.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bajwa SJ, Bajwa SK, Kaur J, Singh G, Arora V, Gupta S, et al. Dexmedetomidine and clonidine in epidural anaesthesia: A comparative evaluation. Indian J Anaesth. 2011;55:116–21. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.79883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Talke P, Tayefeh F, Sessler DI, Jeffrey R, Noursalehi M, Richardson C. Dexmedetomidine does not alter the sweating threshold, but comparably and linearly reduces the vasoconstriction and shivering thresholds. Anesthesiology. 1997;87:835–41. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199710000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kanazi GE, Aouad MT, Jabbour-Khoury SI, Al Jazzar MD, Alameddine MM, Al-Yaman R, et al. Effect of low-dose dexmedetomidine or clonidine on the characteristics of bupivacaine spinal block. Acta Anesthesiol Scand. 2006;50:222–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2006.00919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Konaki S, Adanir T, Yilmaz G, Rezanko T. The efficacy and neurotoxicity of dexmedetomidine administered via the epidural route. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2008;25:403–9. doi: 10.1017/S0265021507003079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gordh TE, Ekman S, Lagerstedt AS. Evaluation of possible spinal neurotoxicity of clonidine. Ups J Med Sci. 1984;89:266–73. doi: 10.3109/03009738409179507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gordh TE, Post C, Olsson Y. Evaluation of toxicity of subarachnoid clonidine, guanfacine, and a substance P-antagonist on rat spinal cord and nerve roots. Anesth Analg. 1986;65:1303–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eisenach JC, Grice SC. Epidural clonidine does not decrease blood pressure or spinal cord blood flow in awake sheep. Anesthesiology. 1988;68:335–40. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198803000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]