Abstract

Arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis is the gold standard method for assessment of oxygenation and acid base analysis, yielding valuable information about a variety of disease process. This study is aimed to determine the extent of correlation between arterial and peripheral venous samples for blood gases and acid base status in critically ill and emergency department patients and to evaluate if venous sample may be a better alternative for initial assessment and resuscitation. The prospective study was conducted on 45 patients of either sex in the age group of 15-80 years of intensive care unit and emergency ward. Relevant history, presenting complaints, vital signs, and indication for testing were recorded. Arterial and peripheral venous samples were drawn simultaneously in a pre-heparinized syringe and analyzed immediately for blood gases and acid base status. Mean difference and Pearson's product moment correlation coefficient was used to compare the result. After statistical evaluation, the present study shows minimal mean difference and good correlation (r > 0.9) between arterial and peripheral venous sample for blood gases and acid base status. Correlation in PO2 measurement was poor (r < 0.3). Thus, venous blood may be a useful alternative to arterial blood during blood gas analysis obviating the need for arterial puncture in difficult clinical situation especially trauma patients, for initial emergency department assessment and early stages of resuscitation.

Keywords: Arterial blood, blood gas analysis, peripheral venous blood

INTRODUCTION

Arterial blood gas (ABG) has been demonstrated to be the most frequently ordered test in intensive care unit (ICU)[1] and has become so essential in management of critically ill patients that recent critical care guidelines[2] recommend 24 h ABG availability.

Although used to evaluate many respiratory and metabolic conditions, ABG analysis is not without drawbacks. The most common complication associated with arterial puncture is local hematoma; very rarely arterial dissection and thrombosis may occur.[3]

Venous blood sampling may be a useful alternative to ABG sampling, obviating the need for arterial puncture.[4]

Several studies have shown good correlation between arterial and peripheral venous blood gas samples, but authors have differed with respect to whether venous blood can replace arterial blood for ABG analysis.[5,6,7,8]

As abnormal acid base balance is among the best predictor of mortality in critically ill patients, this study is aimed to determine the extent of correlation between arterial and peripheral venous samples for blood gases and acid base status in critically ill and emergency department patients, to evaluate if venous sample may be a better alternative for initial assessment and resuscitation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The present study was conducted on 45 patients in age group of 15-80 years of either sex admitted in casualty and ICU at Nehru Hospital and B.R.D Medical College, Gorakhpur with prior permission of ethical committee.

All patients who required ABG sampling on the basis of their clinical presentation were included in the study. Most of the patients were postoperative, admitted in ICU from emergency surgical/gynaecology/obstetric ward. Other included patients were of septicemia/poisoning, respiratory discomfort, and potential metabolic problems such as diabetic ketoacidosis, renal failure, and seizure disorders.

The following data were prospectively recorded:

Age, sex, presenting complaint, vital signs, and indication for testing.

Arterial and peripheral venous samples were drawn simultaneously in a pre-heparinized syringe to prevent coagulation. Arterial blood was taken from radial/dorsalis pedis artery/any other easily accessible artery (either brachial/femoral in difficult condition). Peripheral venous blood was taken from any easily accessible peripheral vein.

Analysis was done on radiometer ABL 555 series blood gas analysis machine (Radiometer, Copenhagen, Denmark) commonly known as blood gas, electrolyte, and metabolite measuring system. Measuring capabilities of analyzer were pH, PCO2 (partial pressure of carbon dioxide), PO2 (partial pressure of oxygen), electrolytes (sodium, potassium, chloride, bicarbonate), base excess/base deficit, anion gap, hematocrit (Hct), hemoglobin (Hb), P50 and oxygen saturation (SO2). Arterial and peripheral samples were recorded for the above values.

The results were entered into a specifically designed database and we analyzed the data using computation of Pearson's product − moment correlation coefficient.

Statistical evaluation

Mean value was calculated and compared for each variable. Mean difference was calculated between the sample pair. Pearson's product moment correlation coefficient for each of measured blood gas variable was calculated by method of difference.

RESULTS/OBSERVATIONS

Observation of different variable: pH, bicarbonate (HCO3-), base excess, anion gap, Hb, Hct, P50, electrolyte (Na+, Cl-, K+), partial pressure of oxygen (PO2), partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PCO2), oxygen saturation (SO2) were noted and recorded in table.

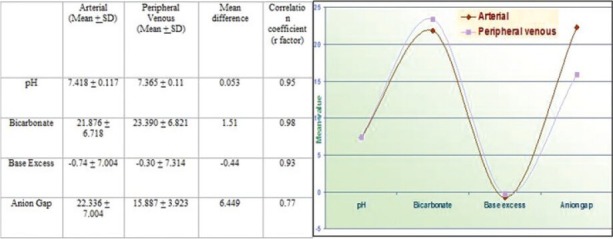

Mean difference and correlation coefficient between arterial and peripheral sample for pH, bicarbonate, base excess shows high correlation (r > 0.9), while anion gap value correlated moderately (r = 0.8) [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Mean difference and correlation coefficient of pH, HCO3–, base excess, and anion gap values for arterial and peripheral venous blood

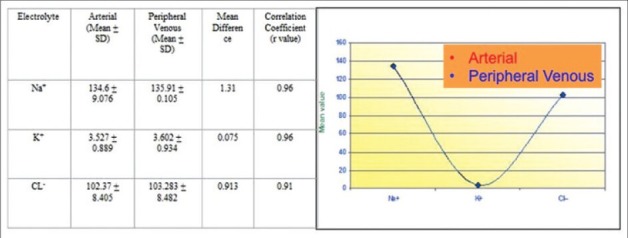

Comparison of electrolyte between arterial and peripheral venous sample shows high correlation (r > 0.9) [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Comparison of electrolyte values (Na+, K+, and CL–) between arterial and peripheral venous samples

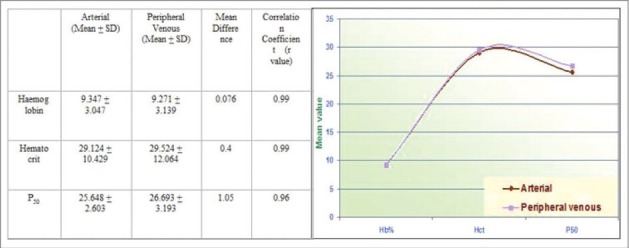

Hb, Hct, P50 values show minimal mean difference and high correlation between sample pair [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Mean difference between arterial and peripheral venous blood for hemoglobin, hematocrit, and P50

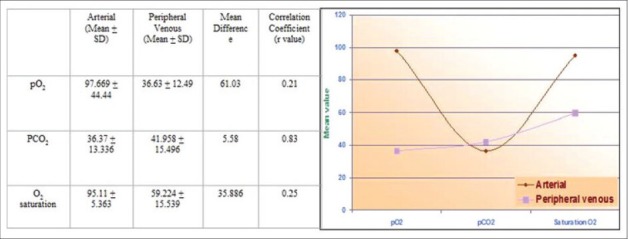

While comparing respiratory parameters, PCO2 value shows high correlation (r > 0.8), while PO2 and SO2 show low correlation coefficient (r < 0.3) [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Comparison of respiratory parameters between arterial and peripheral venous samples

DISCUSSION

ABG analysis has been a cornerstone in the management of acutely ill patients with presumed acid base imbalances, since automated blood analyzers first became available in early 1960s.

Analysis of pH, bicarbonate, and base excess is an important component of the assessment of clinical status and progress of critically ill patients. ABG analyzer provides moment-to-moment information about key circulatory and respiratory physiologic variables and how diseases derange them. Blood gas analysis revolutionized both clinical medicine and cardiorespiratory and metabolic physiology. Apart from helping to establish a diagnosis, measured pH and derived acid base variables may also help to ascertain the severity of a particular condition (metabolic acidosis in sepsis), intensity of monitoring required, and what further intervention should take place.

These variables are usually measured on arterial blood. Access to arterial blood may be problematic, particularly in early stages of resuscitation when arterial line access has to be established.

This study is aimed to determine the extent of correlation between arterial and peripheral venous sample for pH, bicarbonate, base excess, and other values in a group of ICU and critically ill patients.

Kelly et al.,[9] did prospective study of patients to determine their ventilatory or acid base status by comparing pH on arterial and venous sample. The values were highly correlated (r = 0.92) with an average difference between the samples of 0.04 units. They concluded that venous estimation is an acceptable substitute for arterial measurement and may reduce risks of complications both for patients and health care workers. In accordance to above study, we also found good correlation between arterial and venous pH.

Johnston[10] studied agreement between arterial and venous blood in the measurement of potassium in patients with cardiac arrest. It was found that mean difference between each pair of arterial and venous potassium measurement was low at 0.106 m mol/L. Our evaluation of mean difference of K+ (0.147 m-mol/L) is comparable to the author's analysis.

Kelly et al.,[11] also compared arterial and venous sample for PCO2, and found good correlation.

Rang et al.,[12] performed venous blood gas analysis in patients requiring ABG analysis in emergency department. Pearson's product moment correlation coefficients between arterial and venous values were pH (0.913), PCO2 (0.921), and HCO3- (0.953). They concluded that the small mean difference between the sample and strong correlation might preclude using such results interchangeably. As found by the above study, present study also shows good correlation between arterial and venous sample: pH (0.95), PCO2 (0.83), bicarbonate (0.98). Various studies have found a proper correlation between arterial and venous samples regarding the values of pH, PCO2, HCO3 in conditions including diabetic ketoacidosis,[13] trauma,[14] intoxication,[15] patients in critical care unit,[16] and emergency department.[17,18]

An important part of the assessment of clinical status and progress of critically ill patients is analysis of acid base status. However, it may not always be practical to obtain arterial sample, particularly in early stages of resuscitation. For patients managed without arterial line, arterial punctures pose a small but significant risk of complication (AARC clinical practice guidelines, 1992).[19] The finding of this study that arterial and peripheral venous pH, bicarbonate, base excess, and other values showed good correlation might allow venous sampling to be used for measuring these variables in certain settings such as initial resuscitative measure in critically ill patients and for initial emergency department assessment, obviating the need for arterial sampling.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Muakkassa FF, Rutledge R, Fakhry SM, Meyer AA, Sheldon GF. ABGs and arterial lines: The relationship to unnecessarily drawn arterial blood gas samples. J Trauma. 1990;30:1087–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guidelines for standards of care of patients with acute respiratory failure on mechanical ventilator support. Task Force on Guidelines; Society of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 1991;19:275–8. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199102000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barker WJ. Arterial puncture and cannulation. In: Roberts JR, Hedges JR, editors. Clinical Procedure in Emergency Medicine. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1998. pp. 308–22. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malinoski DJ, et al. Correlation of central venous and arterial blood gas measurement in mechanically ventilated trauma patients. Arch Surg. 2005;140:122–5. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.140.11.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelly AM, McAlpine R, Kyle E. Agreement between bicarbonate measured on arterial and venous blood gases. Emerg Med Australas. 2004;16:407–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2004.00642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma OJ, Rush MD, Godfrey MM, Gaddis G. Arterial blood gas results rarely influence emergency physician management of patients with suspected diabetic ketoacidosis. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:836–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb00625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gokel Y, Paydas S, Koseoglu Z, Alparslan N, Seydaoglu G. Comparison of blood gas and acid-base measurements in arterial and venous blood samples in patients with uremic acidosis and diabetic ketoacidosis in the emergency room. Am J Nephrol. 2000;20:319–23. doi: 10.1159/000013607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelly AM, McAlpine R, Kyle E. Venous pH can safely replace arterial pH in the initial evaluation of patients in the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2001;18:340–2. doi: 10.1136/emj.18.5.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Middleton P, Kelly AM, Brown J, Robertson M. Agreement between arterial and central venous values for pH, bicarbonate, base excess, and lactate. Emerg Med J. 2006;23:622–4. doi: 10.1136/emj.2006.035915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnston HL, Murphy R. Agreement between an arterial blood gas analyser and a venous blood analyser in the measurement of potassium in patients in cardiac arrest. Emerg Med J. 2005;22:269–71. doi: 10.1136/emj.2003.013599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelly AM, Kyle E, McAlpine R. Venous pCO2 and pH can be used to screen for significant hypercarbia in emergency patients with acute respiratory disease. J Emerg Med. 2002;22:15–9. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(01)00431-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rang LC, Murray HE, Wells GA, Macgougan CK. Can peripheral venous blood gases replace arterial blood gases in emergency department patients? CJEM. 2002;4:7–15. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500006011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brandenburg MA, Dire DJ. Comparison of arterial and venous blood gas values in the initial emergency department evaluation of patients with diabetic ketoacidosis. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;31:459–65. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(98)70254-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malinoski DJ, Todd SR, Slone S, Mullins RJ, Schreiber MA. Correlation of central venous and arterial blood gas measurements in mechanically ventilated trauma patients. Arch Surg. 2005;140:1122–5. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.140.11.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eizadi-Mood N, Moein N, Saghaei M. Evaluation of relationship between arterial and venous blood gas values in the patients with tricyclic antidepressant poisoning. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2005;43:357–60. doi: 10.1081/clt-200066071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bilan N, Behbahan AG, Khosroshahi AJ. Validity of venous blood gas analysis for diagnosis of acid-base imbalance in children admitted to pediatric intensive care unit. World J Pediatr. 2008;4:114–7. doi: 10.1007/s12519-008-0022-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malatesha G, Singh NK, Bharija A, Rehani B, Goel A. Comparison of arterial and venous pH, bicarbonate, PCO2 and PO2 in initial emergency department assessment. Emerg Med J. 2007;24:569–71. doi: 10.1136/emj.2007.046979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kelly AM. Review article: Can venous blood gas analysis replace arterial in emergency medical care. Emerg Med Australas. 2010;22:493–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2010.01344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.AARC clinical practise guidelines Sampling of arterial blood gas analysis. American Association for Respiratory Care. Respir Care. 1992;37:913–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]