Abstract

Introduction:

With the advent of ultrasound (US) guidance, this technique saw resurgence in the late 1990s. As US guidance provides real-time view of the block needle, the brachial plexus, and its spatial relationship to the surrounding vital structures; it not only increased the success rates, but also brought down the complication rates. Most of the studies show use of US guidance for performing brachial plexus block, results in near 100% success with or without complications. This study has been designed to examine the technique and usefulness of state-of-the-art US technology-guided supraclavicular brachial plexus block and compare it with routine nerve stimulator (NS)-guided technique.

Aim:

To note block execution time, time of onset of sensory and motor block, quality of block and success rates.

Settings and Design:

Randomized controlled trial.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 60 patients were enrolled in this prospective randomized study and were randomly divided into two groups: US (Group US) and NS (Group NS). Both groups received 1:1 mixture of 0.5% bupivacaine and 2% lignocaine with 1:200000 adrenaline. The amount of local anaesthetic injected calculated according to the body weight and not crossing the toxic dosage (Inj. bupivacaine 2 mg/kg, Inj. lignocaine with adrenaline 7 mg/kg). The parameters compared between the two groups are block execution time, time of onset of sensory and motor block, quality of sensory and motor block, success rates are noted. The failed blocks are supplemented with general anesthesia.

Statistical Analysis:

The data were analyzed using the SPSS (version 19) software. The parametric data were analyzed with student “t” test and the nonparametric data were analyzed with Chi-square test A P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results:

There was no significant difference between patient groups with regard to demographic data, the time of onset of sensory and motor block. Comparing the two groups, we found that the difference in the block execution time and success rates is not statistically significant. A failure rate of 10% in US and 20% in NS group observed and is statistically insignificant (P = 0.278). No complication observed in either group.

Conclusions:

US and NS group guidance for performing supraclavicular brachial plexus blocks ensures a high success rate and a decreased incidence of complications that are associated with the blind technique. However, our study did not prove the superiority of one technique over the other. The US-guided technique seemed to have an edge over the NS-guided technique. A larger study may be required to analyze the advantages of using US in performing supraclavicular brachial plexus blocks, which could help justify the cost of purchase of the US machine.

Keywords: Brachial plexus block, nerve stimulator, supraclavicular, ultrasound

INTRODUCTION

The brachial plexus block can be performed by blind; nerve stimulator (NS)-guided or ultrasound (US)-guided technique. A patient need not be subjected to the discomfort of paresthesia when the nerve is stimulated to produce a motor twitch, because motor fibers have a lower electrical threshold than sensory fibers.[1] The use of the NS technique, however, did not reduce the complication rates. Therefore, the supraclavicular block remained less popular among other approaches to the brachial plexus.

With the advent of US guidance, this technique saw resurgence in the late 1990s. As it provides real-time view of the block needle, the brachial plexus and its spatial relationship to the surrounding vital structures, it not only increased the success rates, but also brought down the complication rates. In this prospective randomized study, we compared US-guided supraclavicular brachial plexus block with the NS-guided technique and evaluated onset, quality of sensory and motor block, success rate, block execution time, failure rate, and complications if any noticed.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

After approval by the ethics committee and written informed consent obtained from all patients, 60 patients who satisfied the inclusion and exclusion criteria, undergoing surgeries of the distal arm, forearm or hand, were selected for the study.

Inclusion criteria

ASA (American society of anaesthesiologists) 1, 2, and 3 patients, age between 18 and 75 years.

Exclusion criteria

Patients who refuses to participate in the study, infection at the proposed site of block, coagulopathies, and allergy to local anesthetics, pulmonary pathology and preexisting neurological deficit in the upper limbs.

All the patients were fasted adequately and were premedicated with tab. diazepam 10 mg and tab. ranitidine 150 mg on the night before surgery and on the morning of surgery. In the operation theatre, patients were monitored with pulse oximetry, non invasive blood pressur, and Electro Cardiogram. After establishing an intravenous access, the patients received inj. midazolam 2 mg intravenously. No other sedation was given till evaluation of the block was completed. The operator who has undergone 1 year training in US-guided nerve block performed the blocks in US group.

The patients were randomly allotted by closed envelope technique into either of the two groups namely, US-guided (group US) or NS-guided (group NS). The respective equipment kept ready and the drugs were loaded maintaining sterility. The drug used was a 1:1 mixture of 0.5% bupivacaine and 2% lignocaine with 1:200000 adrenaline. The amount of local anesthetic injected calculated according to the body weight and not crossing the toxic dosage (inj. bupivacaine 2 mg/kg, inj. lignocaine with adrenaline 7 mg/kg). The patients were positioned supine with the arms by the side and head turned to the opposite side by 45°. The proposed site of block was aseptically prepared and draped.

Group US

A Sonosite Micromax-HFL linear 38 probe (6-13 MHz) was used for conducting the block in every case. The probe was inserted into a sterile plastic sheath so as to maintain sterility. It was then placed in the coronal oblique plane in the supraclavicular fossa. The subclavian artery, vein, and the brachial plexus were visualized. The brachial plexus and its spatial relationship to the surrounding structures were scanned. The plexus was identified superolateral to the subclavian artery consistently in all the cases. Next, skin was anesthetized at the proposed site of entry with 1% lignocaine (1-2 mL) and a 20 G, 50 mm needle was connected to a 50 cm extension line and primed with the drug. It was inserted from the medial to lateral direction and the needle movement was observed in real time. Once the needle reached the plexus, after negative aspiration, drug was injected and the spread of the drug was observed. When necessary, the needle was repositioned to achieve an ideal perineural distribution of the drug.

Group NS

In this group, the positive electrode of the NS was attached to an ECG lead and stuck on the ipsilateral arm. The subclavian artery was then palpated and immediately lateral to it, an intradermal wheal was raised with 1% lignocaine (2 mL) using a 24 G needle. A 20 G insulated needle attached to the negative electrode of the NS was then inserted through the skin wheal in a backward, inward, and downward direction. NS was set to deliver a current of 1.5 mA in the internal mode.

After finger flexion was elicited with stimulation, the current was reduced in steps of 0.2 mA till the presence of a muscle twitch with 0.6 mA was observed and no twitch with a current of 0.2 mA was observed. This confirms the proximity of the needle tip to the nerve and the drug was injected after negative aspiration for air or blood.

The sensory and motor blocks were then assessed by an independent observer who is not aware of the technique used for every 2 min till the onset of block and every 5 min thereafter for 30 min. Any failure in establishing the block was converted to general anesthesia.

Definitions

Block execution time

In the group US, it is calculated from the time of initial scanning to the removal of the needle.

In the group NS, it is the time from the time of insertion of the needle to its removal.

Time of onset of sensory block

It was assessed by pin prick and cold application every 2 min till the onset of sensory block. The time from the removal of block needle to the time when the patient first says he/she has reduced sensation when compared to the opposite limb.

Time of onset of motor block

The onset of motor blockade was assessed every 2 min till the onset of motor block. It is the time of removal of the block needle to the time when the patient had weakness of any of the three joints − Shoulder, elbow, or wrist, upon trying to perform active movements.

Quality of sensory block

The quality of sensory block was assessed every 5 min after the onset was established. It was assessed using pin prick and application of ice cold water. At the end of 30 minutes, the quality of sensory block was assessed by the number of dermatomes having a full block. The sensory block in each dermatome was graded as follows:

Blocked: Complete absence of sensation

Patchy: Reduced sensation when compared to the opposite limb

No block: Normal sensation.

Quality of motor block

The quality of motor block was assessed every 5 min after the onset was established. It was assessed by asking the patient to perform active movements of each of the three joints − Shoulder, elbow, and wrist. The motor bock at each joint was graded as follows:

Blocked: No power

Patchy: Able to move actively

No block: Full power.

Success

We considered our block to be successful when the patient had a full block of all the sensory dermatomes and no power to move above-mentioned joints.

Failure

Failure was defined as the absence of full sensory block in at least one dermatome.

Postoperatively, pain was assessed using visual analogue scale (VAS) score every 30 min. Patients were supplemented with analgesics when they complained of pain or when a VAS score of more than 4 was recorded, and the duration of analgesia was noted. The patients were also asked if any region of the limb remained insensible/weakened or generated abnormal sensations for a prolonged period of time.

The data were analyzed using the SPSS (version 19) software. The parametric data were analyzed with student “t” test and the nonparametric data were analyzed with Chi-square test. A P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

There were no significant differences between both the groups with respect to demographic parameters such as age, height, weight, and gender.

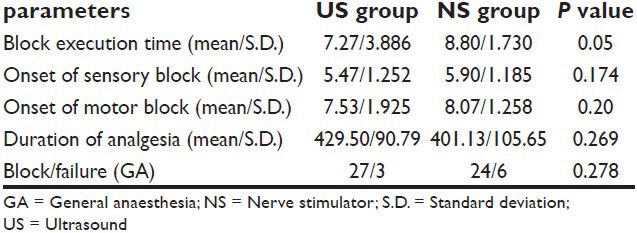

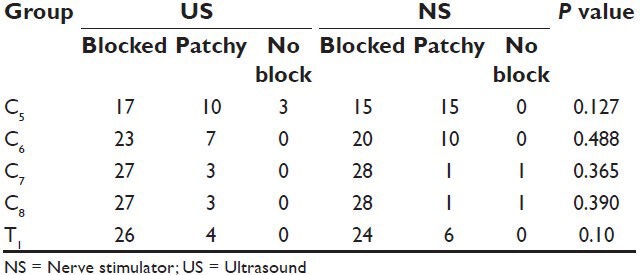

As shown in Table 1, no statistical significant difference in block execution time in both the groups. There is no difference in onset of sensory and motor block in both groups. Although the duration of analgesia is more with the US group, this was not statistically significant. In the group US, three patients had no block of the C5 dermatome. No other dermatomes were completely spared in the group US. Full sensory blockade was achieved in 17, 23, 27, 27, and 26 patients in the C5, C6, C7, C8, and T1 dermatomes, respectively.

Table 1.

Parameters in both ultrasound and nerve stimulator groups

In the group NS, one patient had no block of the C7 and C8 dermatomes. No other dermatomes were completely spared in the group NS. Full sensory blockade was achieved in 15, 20, 28, 28, and 24 patients in the C5, C6, C7, C8, and T1 dermatomes, respectively. When comparing between the corresponding dermatomes of the two groups, there was no statistically significant difference [Table 2].

Table 2.

Quality of sensory block in groups ultrasound and nerve stimulator

In both group US and group NS, 14 (46%) patients each had a full block of all the five dermatomes, which translates into equal success rates in either groups in our study.

The quality of motor block was assessed in the three joints, wrist, elbow, and shoulder. In the group US, two patients had no motor blockade of the wrist joint. No other joints were completely spared in the group US. Full motor blockade was achieved in 26, 27, and 16 patients in the wrist elbow and shoulder joints, respectively.

In the group NS, three patients had no motor blockade of the shoulder joint. No other joints were completely spared in the group NS. Full motor blockade was achieved in 26, 23, and 12 patients in the group NS. When comparing between the corresponding dermatomes of the two groups, there was no statistically significant difference.

Fifteen patients in group US and twelve patients in group NS had a full motor blockade of all the three joints. When comparing the two groups, we found that the difference in the success rates of motor block is not statistically significant (P = 0.436).

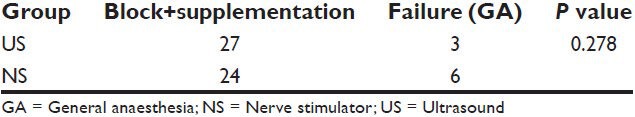

Three patients in group US and six patients in group NS required GA for completion of surgery. This implies a failure rate of 10% and 20%, respectively. This difference was found to be statistically insignificant (P = 0.278) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Failure rate in groups ultrasound and nerve stimulator (GA conversion rate)

No complications were observed in any of the patients in either group.

DISCUSSION

This prospective randomized study was aimed at determining how useful US guidance is when compared with NS guidance for performing a supraclavicular brachial plexus block. A successful brachial plexus block depends not only on the technique used, but also on the experience of the anesthetist, patient's body habitus, amount and type of drug injected, the level of motivation of the patient, and the definition of a successful block.[2]

A successful block in our study was defined as a block that resulted in a full sensory block of all the five dermatomes. With this definition, we achieved a success rate of 46.6% (14 out of 30) in each group. These results compared with the 40% success rate using similar criteria, described by Gaertner et al.[3] In our study, we observed that 90% (27 out of 30) and 80% (24 out of 30) cases were done without general anesthesia in groups US and NS, respectively. These values are similar to those obtained by other investigators, who have defined success as the ability of the block to carry out the surgery without general anaesthesia being instituted.[4,5]

We had 13 cases in Group US and 10 cases in Group NS that were operated without general anesthesia, in spite of having partial blocks in one or more sensory dermatomes. This apparent success could be due to one the following reasons; patients had an increased tolerance to pain, surgery involved only those dermatomes that were fully blocked, delayed completion of sensory block beyond 30 min.

Delayed completion of sensory block has also been suggested by Kapral et al.,[6] in his study. He showed that up to 50 min may be necessary to attain full sensory blockade with a single shot US-guided supraclavicular block. The study by Franco and Vieira,[7] performing NS-guided supraclavicular blocks had the greatest success rates (973 of 1003). This clearly shows that extensive experience with supraclavicular blocks and a longer evaluation period can lead to increased success rates.

The block execution time in our study was comparable between the two groups (7.27 ± 3.88 min in group US and 8.8 ± 1.73 min in group NS), although few other studies have proved that US-guided technique was performed faster than NS-guided technique.[2] The time required in the studies involving the use of both US and NS simultaneously was higher than in our study.[4]

Studies that involved the use of both US guidance and nerve stimulation simultaneously to confirm the needle position before injection had a success rate of 90%-95%.[2,4,5] In order to bring out the use of the NS as an adjunct to US guidance, a study was done by Beach et al.[8] They concluded that the use of a NS does not improve the efficacy/success rates of US-guided supraclavicular blocks. If at all, it could only prolong the block execution time.

The onset of motor blockade followed that of sensory block in our study and was comparable to one other similar study by Chan et al.,[5] the duration being 5.4 ± 1.8 min. The duration of analgesia in our study was 429.5 ± 90.79 min and 401.1 ± 105.65 min in the groups US and NS, respectively. This was comparatively shorter when compared with a similar study using the same drug combination as ours. The study was conducted by Williams et al.,[2] and the duration was 846 ± 531 min and 652 ± 473 min in the groups US and NS, respectively.

To make a note on the quality of sensory block achieved in our study, in both the groups, complete anesthesia at 30 min was achieved more reliably and rapidly in the dermatomes C6, C7, C8, and T1, as compared with C5 dermatome. There was no statistically significant difference in the degree of sparing of the C5 dermatome between the two groups US and NS.

We had a failure rate of 10% (three cases) in the group US and 20% (six cases) in group NS. In group NS, two patients had a partial block of C5 and C6 dermatomes and one patient had a partial block in C5, C6, C7, and T1 dermatomes. As all these patients were undergoing surgeries on the radius, the block was inadequate to complete the surgery and had to be converted to GA. One patient undergoing surgery on both forearm bones had a partial block in C5, C6, C8, and T1, which would explain the failure of block and the necessity for GA. The other two patients were undergoing surgeries on the elbow and had a partial block in C5, C6, and T1, which necessitated conversion to GA.

The three failures in the group US were all undergoing surgeries on both the forearm bones. All of them had partial blocks in C6 to T1 and no block in C5 and hence required conversion to GA. A study examining the number of brachial plexus blocks required to attain a reasonable degree of proficiency with the technique estimated that at least 62 blocks should be performed to achieve a success rate of 87%.[2]

In the study by Hickey et al., involving subclavian paravascular block, the subclavian artery was inadvertently punctured in 25.6% cases and the recurrent laryngeal nerve was blocked in 1.3% cases.[9] One of the most important advantages of using US for brachial plexus block is the direct visualization of the needle tip in relation to the cervical pleura, thus minimizing the chances of an accidental pleural puncture. In our study, there were no cases of accidental puncture of the subclavian vessels nor were there any cases of recurrent laryngeal nerve or phrenic nerve blocks. Renes et al.,[10] in their study proved that hemidiaphragmatic paresis can be avoided by US guidance. In the study done by Liu et al.,[11] which compared US-guided axillary block with NS-guided axillary block, they concluded that the incidence of adverse events was significantly higher in the NS group (20%) compared with that in the US group (0%); (P = 0.03).

There are some advantages of US guidance in brachial plexus blocks, as it can determine the size, depth, and exact location of the plexus and its neighboring structures. A preblock anatomical estimation can be done, which can help avoid complications and improve success rates as well as provide confidence to the anesthesia provider.[5] Yet another advantage of US guidance is that, due to the correct needle placement and visualization of the spread of drug, smaller than usual amount and volume of drug can be used to achieve a satisfactory and dense blockade. In the study conducted by Searle and Niraj,[12] the volume of drug used was as low as 25.7 ± 5 mL, with 84% of the patients reporting that the quality of anesthesia was excellent. This will not replace the conventional techniques as the machine itself is not cost-effective and in developing and under developed countries cost is a one of the important factor.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study did not prove the superiority of one technique over the other. The US-guided technique seemed to have an edge over the NS-guided technique. A larger study may be required to analyze the advantages of using US in performing supraclavicular brachial plexus blocks, which could help justify the cost of purchase of the US machine.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pither C, Ford D, Raj P. Peripheral nerve stimulation with insulated and uninsulated needles: Efficacy of characteristics. Reg Anesth. 1984;9:73–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams SR, Couinard P, Arcand G, Harris P, Ruel M, Boudreault D, et al. Ultrasound guidance speeds execution and improves the quality of supraclavicuar block Anesth Analg. 2003;97:1518–23. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000086730.09173.CA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lanz E, Theiss D, Jankovic D. The extend of blockade following various techniques of brachial plexus block Anesth Analg. 1983;62:55–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsui BC, Doyle K, Chu K, Oippay J, Dillane D. Case series Ultrasound-guided supraclavicular block using a curvilinear probe in 104 day-case hand surgery patients. Can J Anesth. 2009;56:46–51. doi: 10.1007/s12630-008-9006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan VW, Perlas A, Rawson R, Odukoy O. Ultrasound-guided supraclavicular brachial plexus block Anesth Analg. 2003;97:1514–7. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000062519.61520.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kapral S, Krafft P, Eibenberger K, Fitzgerald R, Gosch M, Weinstabl C. Ultrasound-guided supraclavicular approach for regional anaesthesia of the brachial plexus Anesth Analg. 1994;78:507–13. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199403000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Franco CD, Vieira ZE. 1001 subclavian perivascular brachial plexus blocks: Success with a nerve stimulator. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2000;25:41–6. doi: 10.1016/s1098-7339(00)80009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beach ML, Brian D, Gallagher JD. Use of a nerve stimulator does not improve the efficacy of ultrasound-guided supraclavicular nerve blocks. J Clin Anaesth. 2006;18:580–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2006.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hickey R, Garland TA, Ramamurthy S. Subclavian paravascular block: influence of location of parasthesia Anesth Analg. 1989;68:767–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Renes SH, Spoormans HH, Gielen MJ, Rettig HC, van Geffen GJ. Hemidiaphragmatic paresis can be avoided in ultrasound-guided supraclavicular brachial plexus block. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2009;34:595–9. doi: 10.1097/aap.0b013e3181bfbd83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu FC, Liou JT, Tsai YF, Li AH, Day YY, Hui YL, et al. Efficacy of ultrasound guided axillary brachial plexus block: A comparative between nerve stimulator guided method. Chang Gung Med J. 2005;28:396–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Searle A, Niraj G. Ultrasound-guided brachial plexus block at the supraclavicular level: A new parasagittal approach. Int J Ultrasound Appl Technol Perioper Care. 2010;1:19–22. [Google Scholar]