Abstract

Context:

Anaesthesia during cleft lip and palate surgery carries a high risk and difficult airway management in children.

Aim:

to study the perioperative anesthetic complications in poor children with cleft abnormalities.

Settings and Design:

Retrospective analysis.

Materials and Methods:

This retrospective audit was conducted on 2917 patients of smile train project under going general anesthesia for cleft lip and palate from January 2007 to December 2010. Demographic, pre-anesthetic status, anesthetic management and anesthesia complications were recorded. Chi-square test was used to assess the relation between patient factors and occurrence of complications.

Results:

Of the 3044, we were able to procure complete data of 2917 patients. Most of children presented with anemia 251 (35%), 202 (29%) had eosinophilia while 184 (26%) had upper respiratory tract infection. The incidence of perioperative complications was 8.19% of which 33.7% critical incidents occurred during the induction time. The most common complication was laryngospasm 77 (40.9%) followed by difficult intubation 64 (30.9%). There was no mortality.

Conclusion:

Since these procedures do not characterize an emergency, most of the perioperative complications can be prevented by following the routine installed by the institute and smile train protocols.

Keywords: Anesthesia techniques, cleft lip, complications, palate, perioperative period, smile train

INTRODUCTION

Ever since the first anesthesia administered for cleft lip repair by John Snow in 1847, the Anesthesiologists have been striving to search the ideal anesthesia technique for craniofacial operations.[1,2]

The majority of anesthesia complications related to craniofacial abnormality is difficulty with intubation, intra-operative monitoring, post-operative airway obstruction.[2,3]

Smile train is an international charity with an aim to restore satisfactorily facial appearance and speech for poor children with cleft abnormalities who otherwise could not be helped.[4] Financial, logistic and training support to cleft teams in developing countries is likely to lead to more surgeries with cleft.[5]

Pediatric anesthesia is a complex dynamic system wherein there is interaction between human beings, machine and the environment. Failures of any component of this system could be harmful to the patient giving rise to critical incidents.[6,7]

With this background, the present study was conducted to analyze and critically review the perioperative anesthetic complications, which occurred during the cleft surgeries performed at the center.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After obtaining permission from the institutional ethics committee the anesthesia protocols and complications for 3044 patients with varying degree of cleft deformities who underwent smile train surgery at our center from 1st January 2007 to 31st December 2010 were reviewed. A total of 3044 patients were operated in the above mentioned duration, but we were able to review 2917 cases in the final evaluation. Parents of a child with severe congenital heart disease refused surgery while 126 cases were not included as there cords were incomplete.

All anesthesia techniques and complications were evaluated on the basis of anesthesia records, case sheets and departmental monthly audits. The data recorded was demographic profile, pre-operative status of patient, premedication, anesthesia technique followed, significant perioperative complication its management and recovery. The complications were classified as minor or severe based on the classification by Cohen et al.[8]

For the purpose of analysis patients were divided into 6 age groups 0-6 months, 6 months to 2 years, 3-4 years, 5-9 years, 10-14 years and ≥15 years.

Chi-square test was used to assess the relation of age and co-morbid conditions to occurrence of complications.

RESULTS

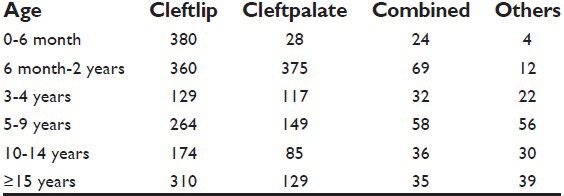

This is a hospital based study where facilities and trained anesthetists are relatively available. Anesthetic management was entirely at the discretion of the individual anesthesia provider, but in accordance with the smile train protocols. Informed consent was taken in all cases. The youngest patient undergoing cleft lip was 4 weeks old and the oldest patient was 64 years old. The highest concentration of patient was in the age group 6-24 months and ≥15 years [Table 1].

Table 1.

Distribution of patients according to age and operative procedure

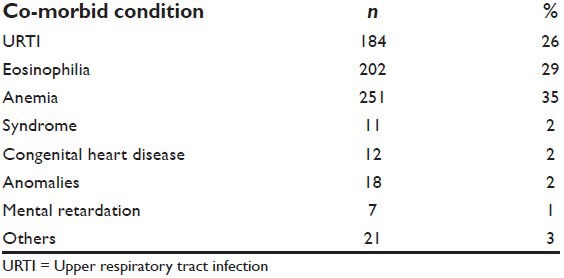

Majority of patients were males 1843 (63.2%) while the total number of female patients was 1074 (36.8%). All patients belonged to American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status (ASA grade) I and II. All patients had undergone routine pre-anesthetic check-up. 706 (20.4%) subjects had associated co-morbid conditions [Table 2].

Table 2.

Pre-existing co-morbid conditions

The fasting guide lines as per the protocols were followed. In 2007-2008 in children <6 months, the trend was to avoid any form of premedication and above 6 months syrup phenergan 1 mg/kg was administered while in older children intramuscular ketamine premixed with glycopyrrolate was routinely administered.

However from 2009 until date, oral midazolam syrup 0.25 mg/kg half hour prior to the surgery and in older patients tab midazolam was prescribed. All patients had undergone strict vigilant perioperative monitoring, which included pulse oximetry, electrocardiography, non-invasive blood pressure monitoring, capnography, axillary temperature monitoring and precordial stethoscope. The body temperature was stabilized by using warm blankets.

Halothane was administered in 15.9% (465) children who were <5 years until 2007 end, thereafter sevoflurane 51.9% (1515) replaced it and is now a preferred inhalational agent. Propofol 28.9% (843) was preferred over thiopentone 3.2% (94) in adult patients. Appropriate analgesia was ensured in all cases. Morphine was prevalent and given in 50.1% (1462), but has been completely replaced by fentanyl in 49.9% (1455) subjects.

In a majority of patients, the maintenance of anesthesia was with isoflurane and muscle relaxant like atracurium or vecuronium with controlled ventilation. Oxford tube was used as the one preferred by the surgical team for both cleft lip and palate.

For eye protection tegaderm film 3 M (6 cm × 7 cm) cut into two equal halves was used. In no case intraoperative blood transfusion was required. Tongue suture was placed after palate surgery to allow forward retraction of the tongue to prevent potential post-operative airway obstruction.

Various modalities like intramuscular/intravenous paracetamol, diclofenac sodium suppositories and tramadol have been used for post-operative analgesia by the concerned anesthesia provider for cleft palate. As an alternative modality, surgeons performed local infiltration in surgical wound empirically reduced post-operative pain. All the cleft lip cases were given infraorbital nerve block for post-operative surgery. The trend initially was to give a block at the end of surgery, but the recent trend is to give it just after intubation.

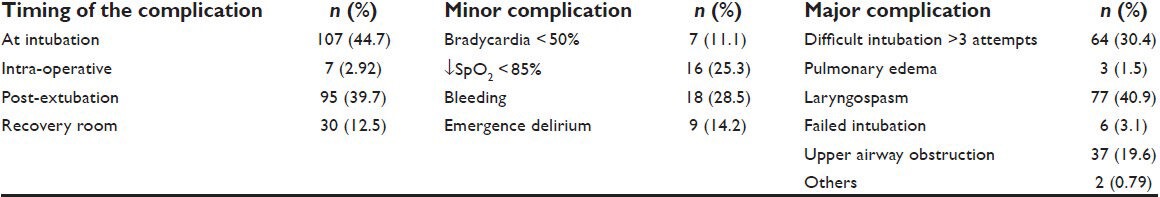

Total number of complication, which occurred was 239 (8.19%) with majority 107 (44.7%) occurring at the time of induction. There was no mortality [Table 3].

Table 3.

Incidence of perioperative complications

The most common complication was laryngospasm in 77 (40.9%) patients of which 34 (44.15%) children were <1 year old, 24 (31.17%) were posted for cleft palate and 26 (33.76%) had a previous history of upper respiratory obstruction. Most commonly, the laryngospasm occurred at the time of extubation. It was observed more in patients who were induced with sevoflurane than with halothane. Patients were managed with 100% oxygen and gentle intermittent positive pressure ventilation.

The second most common complication was difficult in tubationin 64 (30.4%) patients, which mostly occurred in children <1 year in 32 (50%). 28 (43.7%) had both cleft lip and palate deformity while 13 (20.3%) had a bilateral cleft lip. Of these 21 (32.8%) had Cormackand Lehane (CL) grade IIb and III. Four children had CL grade IV. One child with CL grade IV was rescheduled for surgery and was later intubated using Tru-View, two patients were intubated by the senior consultant while one patient had a history of operated tracheoesophageal fistula at birth and the child was malnourished. The parents were advised to bring the child after some weight gain, but they never came in follow-up. In most of the cases 21 (32.8%) external maneuvers like optimal laryngeal external maneuver and in 20 (31.2%) subjects senior anesthetist performed the intubation.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, majority of patients reported for cleft repair at an older age that too probably due to persuasion and motivation of by the health-care workers who had stressed that under the smile train project, the surgical treatment was free and a charity. Efficient health-care delivery during anesthesia and surgery, low morbidity and no mortality may have also motivated other patients to come forward for surgical correction. Patients may have presented in older age due to poverty, ignorance, long distance from cleft care surgical facilities. There is a male preponderance in our audit as most of the surgeries were cleft lip, which is more common in males and palate, which is more common in females.[4,9,10] We found no correlation between sex and occurrence of critical incidence.

There was no statistical association between the nutritional status and anthropometric measurements and post-operative complications, which is consistent with the findings of Biazon and Peniche[11] As the study is retrospective the anthropometrical data was analyzed, but the biochemical, clinical and dietary information could not be elicited.

All patients had undergone pre-anesthetic check as patient selection during the pre-operative assessment is critical for the delivery of safe anesthesia. From September 2008, the institute has formulated a protocol that any child after been advised surgery undergoes a complete pediatric check-up and thereafter undergoes a thorough pre-anesthetic analysis. This has helped us in anticipating and analyzing problems and taking appropriate measures.

Infants having cleft lip with hemoglobin (Hb) 8-10 g/dl were taken for surgery. In children with Hb <8 g/dl; posted for cleft palate or combined surgery were given pre-operative blood transfusion while cleft lip were given hematinic and then taken for corrective surgery. Anemia reflects on the socioeconomic status of patient and poor nutrition due to feeding problems.[1,4]

A common pre-operative finding was eosinophilia (29%), which had an endemic origin. Another common condition the child presented was upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) in 26% subjects. According to Kotour PF, anesthetists are confronted with children demonstrating symptoms of URTI ranging from cough, sneezing, rhinorrhea, sore throat and fever on the day of surgery. The anesthetist maybe pressurized by the surgeon, hospital management and parents to accept the patient for anesthesia on social and/or economic grounds as postponement of surgery disappoints surgeon and parents alike.[12] The incidence of laryngospasm is 1.7%, which rises to 9.6% in children with pre-operative URTI.[12,13] Our institute follows the general outlines given by Chan to follow in such patients.[14]

Airway pressure monitoring and capnography tracing were carried out, which emphasizes the importance of adequate monitoring for early detection of tube compression and displacement. Despite all the sophisticated monitoring devices, the importance of clinical monitoring cannot be ruled out.

The retrospective studies show a complication rate of 14.2-58%,[2,11,15,16] whereas we observed a complication rate of 8.1%. Most of the complications (42.2%) were observed in children <2 years. There was no mortality observed among our patients, which draws the conclusion that most of the incidents are avoidable.

Previous studies have demonstrated that CL grade III and IV was found to be 3% in patients with unilateral cleft lip, 45.8% in patients with bilateral cleft lip and 34.8% in patients with retrognathia.[17,18] In our study, most cases of difficult intubation in children belonged to age group <2 years and in 20.3% children with bilateral cleft or retrognathia.

The low incidence of failed intubation 0.16% recorded was probably because every patient was considered to be potentially difficult airway by Anesthesiologists, preparations were carried out in anticipation well ahead of time. The difficult intubations were managed successfully by the presence of senior consultant, stringent monitoring, positioning the patients by use of a shoulder roll, optimal laryngeal external maneuver, stylet, more caution and extra vigilance. Intubation in our series may have been successful as straight bladed laryngoscope was used in infants and neuromuscular blocking agent was given to facilitate intubation after the ability to ventilate the lungs manually had been confirmed. The practice to reassess ventilation after tube fixation, oral packing and positioning and gag application has helped us. This has reduced the incidence of tube misplacement, disconnection and kinking.

We observed a high incidence of complication during the induction time 44.7%. This is in accordance to findings of Cooper et al.[19] who suggested that intubation, which lasts for 6 min in a 60 min surgery is an incident rich period. In accordance with Edomwonyi et al. we also observed that the incidence of intraoperative complication was higher than complications in the recovery room.[20]

The physiological changes that occur during anesthesia and surgery is not immediately reversed after the end of procedure and several associated complications during the 1st h after the surgery.[21] Thus, immediate post-operative period is the time when patients are more prone to develop oxygen desaturation.

Few prospective studies exist and 5% rate of immediate upper airway obstruction has been reported and occurs in children with associated syndromes because of critical decrease in size of previous tenuous airway, excessive sedation and laryngeal edema.[22]

According to Wood, age between 44 weeks and 74 weeks after birth is when children have demonstrated greater vulnerability to the event of oxygen desaturation in the post-operative period.[23] In our study, the age group in which incidence of desaturation occurred commonly was in subjects <9 months with the significant statistical association between the age group and oxygen desaturation. As compared to cleft lip surgery, palate is considered to be a high-risk for post-operative hypoxemia, which is in accordance to our study.[24]

Quershi et al. have reported hypothermia as an important complication found most commonly in children with a bilateral cleft lip repair citing prolonged duration of surgery as the cause.[2] However, in our series hypothermia was not observed as adequate measures were taken.

A study in our department compared local anesthesia (LA) plus clonidine and LA alone in infra orbital nerve block (IONB). The study concluded that addition of clonidine as an adjunct to local anesthetic significantly decreased the requirement of other anesthetic drugs and significantly prolonged the duration of post-operative analgesia without any adverse effects.[25]

Post-operatively the practice is to nurse the children in lateral position to optimize air movement and to minimize the chances of aspiration. The recovery area has an Anesthesiologist resident and consultant on rotation posting. The arm restrains, which prevent elbow flexion were routinely used to keep the child's hand away from the face as to prevent rubbing at stitches, surgical site and intravenous access site. According to the institute regimens, the child is shifted to the high visibility bed in the well-equipped ward once the vitals are stable and there is no evidence of bleeding. The chain of communication to respond for any emergency is well-established.

With this audit, we want to stress the need to maintain good records to avoid loss of valuable data. When critical incidents occur, they must be investigated not with the goal of appropriating blame, but as a means for finding the chain of events and contributing factors that led to it, to prevent any further occurrence. Such an investigation will reveal gaps and inadequacies in the health-care system.[26] We encourage compliance with voluntary reporting. We were able to develop a proficient use of checklist, protocol profile of anesthesia techniques in use and identified important morbidities for further attentions. Human errors are an important factor in the majority of incidents.[27]

The limitation of the study is that there may be some under reporting as it was based on retrospective assessment of adverse events been voluntarily reported as it seems that the Anesthesiologists report major adverse events more accurately and frequently than minor events. Most of the senior Anesthesiologist acts as supervisors and cases are conducted by senior residents and residents. It was noted that many incidents occurred were those, which occur as part of training. Thus, the result may vary from an institute where only staff Anesthesiologists work.

CONCLUSION

A team approach is needed for management of correcting cleft anomaly, which is best provided in a multidisciplinary setting with coordination among the members of the team so as to maintain communication with specialists, patients and their families. Since these procedures do not characterize an emergency most of the perioperative complications can be prevented by following the routine followed by the institute and smile train protocol for safe anesthesia in cleft lip and palate surgeries.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to express our heartfelt gratitude and appreciation to the smile train project and the plastic surgery department for the noble work they are doing.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jones RG. A short history of anaesthesia for hare-lip and cleft palate repair. Br J Anaesth. 1971;43:796–802. doi: 10.1093/bja/43.8.796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quershi FA, Ullah T, Kamran M, Illyas M, Laiq N. Anesthetist experience for cleft lip and cleft palate repair: A review of 172 smile train sponsored patients at Hayat Abad medical complex, Peshawar. JPMI. 2009;23:90–4. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Machotta A. Anesthetic management of pediatric cleft lip and cleft palate repair. Anaesthesist. 2005;54:455–66. doi: 10.1007/s00101-005-0823-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta K, Gupta PK, Bansal P, Tyagi SK. Anesthetic management for smile train a blessing for population of low socioeconomic status: A prospective study. Anesth Essays Res. 2010;4:81–4. doi: 10.4103/0259-1162.73512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donkor P, Bankas DO, Agbenorku P, Plange-Rhule G, Ansah SK. Cleft lip and palate surgery in Kumasi, Ghana: 2001-2005. J Craniofac Surg. 2007;18:1376–9. doi: 10.1097/01.scs.0000246504.09593.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blum LL. Equipment design and “human” limitations. Anesthesiology. 1971;35:101–2. doi: 10.1097/00000542-197107000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manghnani PK, Shunde VS, Chaudhary LS. Critical incidents during anaesthesia “An Audit”. Indian J Anesth. 2004;48:287–94. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen MM, Duncan PG, Pope WD, Biehl D, Tweed WA, MacWilliam L, et al. The Canadian four-centre study of anaesthetic outcomes: II. Can outcomes be used to assess the quality of anaesthesia care? Can J Anaesth. 1992;39:430–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03008706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jagomagi T, Soots M, Saag M. Epidemiologic factors causing cleft lip and palate and their regularities of occurrence in Estonia. Stomatologija. 2010;12:105–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou QJ, Shi B, Shi ZD, Zheng Q, Wang Y. Survey of patients with cleft lip and palate in China who were funded for surgery by the Smile Train Program from 2000 to 2002. Chin Med J (Engl) 2006;119:1695–700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biazon J, Peniche AC. Retrospective study of postoperative complications in primary lip and palate surgery. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2008;42:519–25. doi: 10.1590/s0080-62342008000300015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kotur PF. Surgical repair of cleft lip and palate in children with upper respiratory tract infection. Indian J Anaesth. 2006;50:58–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olsson GL, Hallen B. Laryngospasm during anaesthesia. A computer-aided incidence study in 136,929 patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1984;28:567–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1984.tb02121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan L. Myths of URTI in children for elective surgery. ASEAN J Anaesthesiol. 2007;8:4–8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Canady JW, Glowacki R, Thompson SA, Morris HL. Complication outcomes based on preoperative admission and length of stay for primary palatoplasty and cleft lip/palate revision in children aged 1 to 6 years. Ann Plast Surg. 1994;33:576–80. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199412000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Desalu I, Adeyemo W, Akintimoye M, Adepoju A. Airway and respiratory complications in children undergoing cleft lip and palate repair. Ghana Med J. 2010;44:16–20. doi: 10.4314/gmj.v44i1.68851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hatch DJ. Airway management in cleft lip and palate surgery. Br J Anaesth. 1996;76:755–6. doi: 10.1093/bja/76.6.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gunawardana RH. Difficult laryngoscopy in cleft lip and palate surgery. Br J Anaesth. 1996;76:757–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/76.6.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cooper JB, Newbower RS, Kitz RJ. An analysis of major errors and equipment failures in anesthesia management: Considerations for prevention and detection. Anesthesiology. 1984;60:34–42. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198401000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edomwonyi NP, Isah IJ, Obuekwe ON. Nairobi, Kenya: Expe Pan African Anesthesia Symposium; 2008. Cleft lip and palate repair: Intraoperative and recovery room complications. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kwari DY, Chinda JY, Olasoji HO, Adeosum OO. Cleft lip and palate surgery in children: Anesthetic considerations. Afr J Paediatr Surg. 2010;7:174–7. doi: 10.4103/0189-6725.70420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tremlett M. Anaesthesia for cleft lip and palate surgery. Curr Anaesth Crit Care. 2004;15:309–16. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wood FM. Hypoxia: Another issue to consider when timing cleft repair. Ann Plast Surg. 1994;32:15–8. discussion 19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Henriksson TG, Skoog VT. Identification of children at high anaesthetic risk at the time of primary palatoplasty. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 2001;35:177–82. doi: 10.1080/028443101300165318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jindal P, Khurana G, Dvivedi S, Sharma JP. Intra and postoperative outcome of adding clonidine to bupivacaine in infraorbital nerve block for young children undergoing cleft lip surgery. Saudi J Anaesth. 2011;5:289–94. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.84104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amucheazi AO, Ajuzieogu OV. Critical incidents during anesthesia in a developing country: A retrospective audit. Anesth Essays Res. 2010;4:64–9. doi: 10.4103/0259-1162.73508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ajaj H, Pansalovich E. How safe is anaesthesia in Libya? Internet J Health. 2005;4:2. [Google Scholar]