Abstract

Context:

Post-operative nausea and vomiting (PONV) pose unique challenges in neurosurgical patients that warrant its study separate from other surgical groups.

Setting and Design:

This prospective, randomized, double-blind study was carried out to compare and to evaluate the efficacy and safety of three antiemetic combinations for PONV prophylaxis following craniotomy.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 75 anesthesiologist status I/II patients undergoing elective craniotomy for brain tumors were randomized into three groups, G, O and D, to receive single doses of dexamethasone 8 mg at induction with either granisetron 1 mg, ondansetron 4 mg or normal saline 2 ml at the time of dural closure respectively. Episodes of nausea, retching, vomiting and number of rescue antiemetic (RAE) were noted for 48 h post-operatively.

Statistical Analysis:

Analysis of variance with post-hoc significance and Chi-square test with fisher exact correction were used for statistical analysis. P <0.05 was considered to be significant and P < 0.001 as highly significant.

Results:

We found that the incidence and number of vomiting episodes and RAE required were significantly low in Group G and O compared with Group D; P < 0.05. However, incidence of nausea and retching were comparable among all groups. The anti-nausea and anti-retching efficacy of all the three groups was comparable.

Conclusions:

Single dose administration of granisetron 1 mg or ondansetron 4 mg at the time of dural closure with dexamethasone 8 mg provide an effective and superior prophylaxis against vomiting compared with dexamethasone alone without interfering with post-operative recovery and neurocognitive monitoring and hence important in post-operative neurosurgical care.

Keywords: 5HT3 antagonists, craniotomy, dexamethasone, granisetron, neurosurgical, ondansetron, post-operative nausea and vomiting

INTRODUCTION

Post-operative nausea and vomiting (PONV) pose unique challenges in patients undergoing craniotomy. Firstly, the incidence of post craniotomy nausea and vomiting is relatively high (44-70%).[1] Secondly, in addition to causing fluid and electrolyte imbalances, emesis may precipitate an increase in intracranial and cerebral intravascular pressures, jeopardizing hemostasis and cerebral perfusion.[2] Thirdly, depressed airway reflexes in the immediate post-operative period due to residual effect of anesthetic drugs and involvement of lower cranial nerves augment the chances of pulmonary aspiration.[3] Fourthly, the need for neurocognitive monitoring post-operatively makes use of sedating antiemetic undesirable in these patients.[2]

Antiemetics are the main stay of prophylaxis against PONV.[4] Among them 5HT3 antagonists such as ondansetron and granisetron are considered first-line agents due to their high efficacy and fewer side-effects.[5,6] Granisetron as compared with ondansetron is a more selective and longer acting 5HT3 receptor antagonist; efficacy of which for PONV prophylaxis has been demonstrated after different surgical procedures.[7,8,9,10,11] We routinely use dexamethasone in neurosurgical patients as it reduces perilesional edema and have observed it to augment the antiemetic efficacy of 5HT3 antagonists.[12] However, the relative efficacy of granisetron compared with the prototypical ondansetron has yet not been fully elucidated in patients undergoing elective craniotomy for supratentorial and infratentorial brain tumors. Thus, a prospective, randomized and double-blind clinical study was conducted to compare the efficacy and safety of combination of dexamethasone with granisetron, ondansetron or normal saline (NS) for PONV prophylaxis until 48 h post craniotomy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After institutional Ethical Committee approval and written informed consent, 75 American Society of Anesthesiologist – I/II/III adult patients of either sex and scheduled for elective craniotomy for brain tumors were enrolled in the present study. Patients with Glasgow coma scale <14, not extubated at the end of surgery, on pre-operative antiemetic therapy, previous history of PONV/motion sickness/Gastro esophageal reflux disease and history of allergy to 5HT3 antagonists were excluded from the study.

A routine pre-anesthetic check-up was done for all patients with special reference to history of PONV, smoking and opioid use. Patients were pre-medicated with tablet (tab) ranitidine 150 mg and tab alprazolam 0.25 mg 2 h before surgery. In the operative room the entire standard monitors electrocardiogram (ECG) lead II, non-invasive blood pressure (BP), pulse oximetry (SpO2) and capnography were established and baseline (pre-induction) measurements were recorded. Dexamethasone 8 mg was given to administered to all the patients at induction. Anesthesia was induced with propofol 2-2.5 mg/kg and tracheal intubation facilitated with vecuronium bromide 0.1 mg/kg. Lignocaine 1.5 mg/kg was given 90 s before intubation in order to obtund the hypertensive response to laryngosopy and intubation and subsequent rise in intracranial tension. Propofol 0.5 mg/kg was repeated just prior to intubation. Anesthesia was maintained with nitrous oxide (N2O) (50%) and isoflurane in oxygen. Patients were given intermittent positive pressure ventilation to maintain end tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO2) between 30 and 35 mmHg. Parameters monitored at appropriate intervals included heart rate (HR), BP, ETCO2, SpO2, central venous pressure (CVP) (where indicated) and urine output (UO). Fentanyl 2 μg/kg intravenous (IV) was given initially and supplemented with fentanyl 1 μg/kg IV hourly. Analgesia was supplemented with infiltration of the incision site with 0.25% bupivacaine both at the start and the end of surgery and inj. diclofenac sodium intramuscular (IM) at dural closure. Mannitol 1 g/kg IV was transfused (over 15-20 min) at the start of surgery. Isotonic fluids were given as maintenance and replacement fluids. Colloids like Hydroxy ethyl starch and blood were given as per the losses. At the time of dura closure, patients were randomly assigned to one of the three groups using envelope method to receive: Group G: Granisetron 1 mg IV, Group O: Ondansetron 1 mg IV or Group D: NS IV. Dexamethasone was given at induction and granisetron or ondansetron or NS at the time of dural closure. Study medications were prepared by an anesthetist not involved in PONV monitoring in identical 2 ml syringes.

Neuromuscular blockade was reversed with neostigmine 0.05 mg/kg and glycopyrrolate 0.008 mg/kg and trachea was extubated after signs of adequate neuromuscular reversal. Post-operatively patients were managed in the neurosurgical recovery room for the first 48 h and following parameters were monitored: ECG (L-II), BP, SpO2, HR, CVP (where indicated) and UO. Anesthetists who were blinded to group allocation recorded each episode of nausea, retching and vomiting. All patients were monitored for PONV for 48 h post-operatively after extubation. An episode of PONV was defined as nausea (subjective feeling of the need to vomit), vomiting (expulsion of stomach contents) or retching (an involuntary attempt to vomit but not productive of stomach contents). All episodes of nausea which were immediately followed by retching or vomiting were taken as an episode of retching or vomiting respectively. In case, the patient exhibited all the three symptoms within 1-2 min, it was taken as one episode of vomiting for statistical purposes. Patients who had only nausea (for more than 10 min) without retching or vomiting were taken as an episode of nausea. To calculate incidence of PONV and avoid duplication of results, a patient exhibiting a combination or all the symptoms was taken as one. Injection metoclopramide 10 mg IV was used as the rescue antiemetic (RAE) in the event of patient having nausea lasting more than 10 min duration or an episode of retching or vomiting. All patients were monitored for sedation and it was scored using the following sedation score Grade I - alert/oriented, Grade II - sedated but responsive to verbal commands and Grade III - sedated but responsive to physical stimulation. Degree of analgesia was noted by Visual Analog Scale (VAS) and rescue analgesic diclofenac sodium 1 mg/kg IM was given 8 hourly and also when score was more than 3. Adverse effects like episodes of headache were also noted.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics in the form of mean, standard deviation, frequency and percentages have been calculated for interval and categorical variables, respectively. To see a significant difference among the groups, one-way analysis of variance with post-hoc Bonferroni test has been applied to continuous variables and Chi-square test with fisher exact correction for qualitative data. Statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) version 16.0 has been used for analysis. P < 0.05 was considered to be significant and P < 0.001 as highly significant.

RESULTS

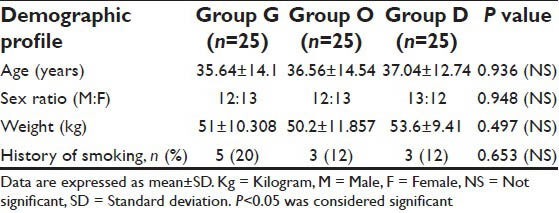

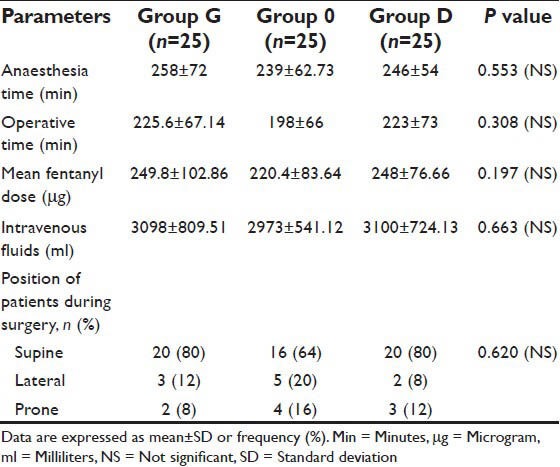

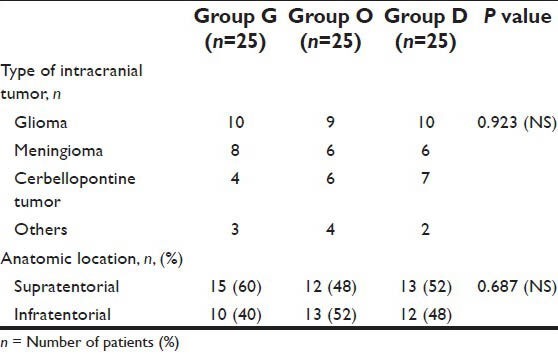

A total of 75 eligible patients were enrolled in the study, 25 in each group. There were no significant differences in demographic profile [Table 1], intra-operational characteristics [Table 2], type and anatomical location of intracranial tumors among the three groups [Table 3].

Table 1.

Demographic data

Table 2.

Intraoperative data

Table 3.

Type and anatomical location of intracranial tumor

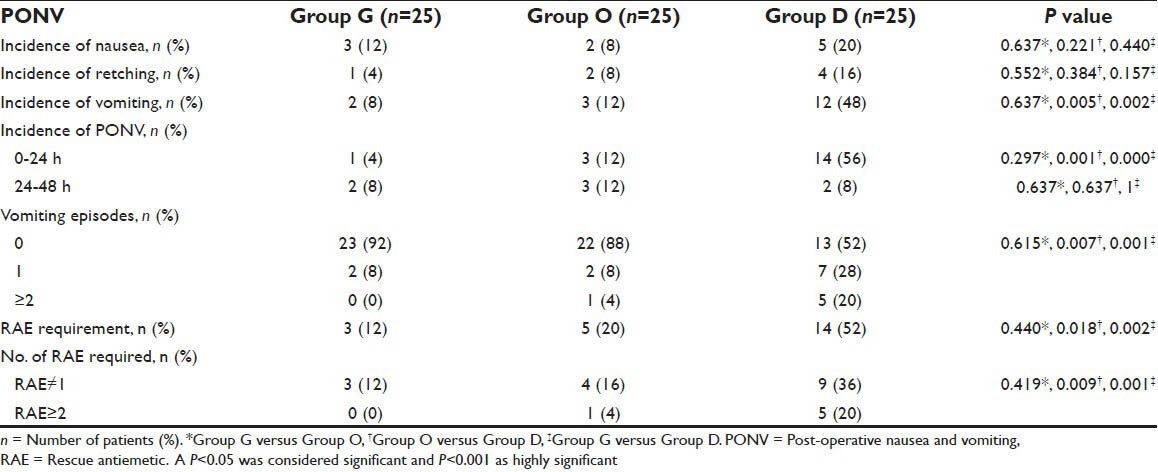

A complete response (no PONV or RAE requirement) occurred in 88%, 76% and 44% in Group G, O and D respectively; P = 0.002. Post-operative vomiting was observed in 8%, 12% and 48% of patients in group G, O and D; P = 0.001 [Table 4]. Nausea (20%) and retching (16%) were frequent in Group D, but comparable among the three groups. Only 12% and 20% patients in Group G and O respectively required RAE, as compared to 52% patients in Group D; P = 0.004. Excessive vomiting (more than equal to two) and frequent RAE (more than equal to two) were observed in 0%, 4% and 20% of patients in group G, O and D respectively; P = 0.003. The incidence of PONV was statistically significant among the groups in first 24 h, P < 0.001; however became statistically insignificant 24-48 h post-operatively; P = 0.854 [Table 4].

Table 4.

Post-operative nausea and vomiting data

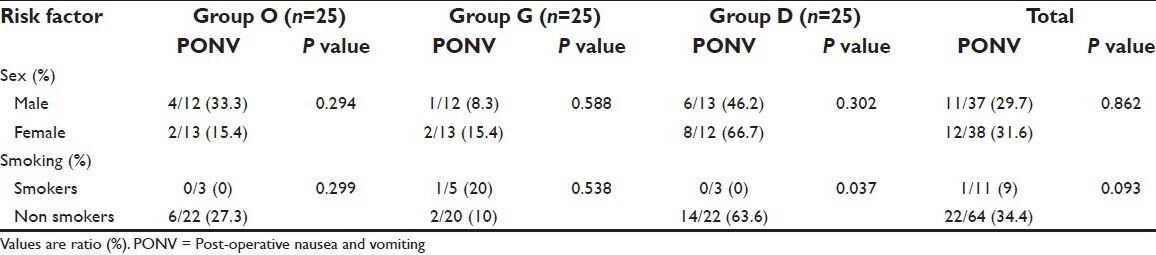

PONV was present in 7/40 (19%) patients and 15/35 (43%) patients undergoing surgery for supratentorial and infratentorial tumors respectively; P = 0.0305. Out of all the patients who had PONV, vomiting was the most common symptom (53%) followed by nausea (28%) and retching (19%). We did not find sex or smoking status of the patient as a predictor of PONV after craniotomy except in group D in which PONV was more frequent among nonsmokers [Table 5].

Table 5.

Sex and smoking status and their relationship with PONV

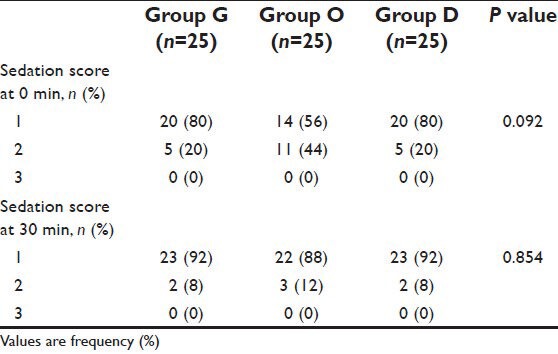

Post-operative sedation (Grade 2 and 3) was observed in 20%, 44% and 20% of patients in Group G, O and D respectively; P = 0.092. None of the patients had a sedation score of III [Table 6]. Headache was observed in 8%, 8% and 0% of patients in Group G, O and D respectively; P = 0.348. No other side-effects such as constipation or confusion were observed in any of the groups. The VAS was comparable among the groups at different time intervals, thus not affecting the results.

Table 6.

Post-operative sedation score

DISCUSSION

This prospective randomized study demonstrated that combination of IV granisetron or ondansetron with dexamethasone significantly reduces the incidence and frequency of PONV episodes, RAE and number of RAE required compared with dexamethasone alone in patients undergoing elective craniotomies. Granisetron with dexamethasone was more effective in preventing PONV as compared to ondansetron but the results did not reach statistical significance. The incidence of PONV without prophylactic 5HT3 antagonists in our study was 56%, which is in accordance with the results of previous authors.[3,10] Vomiting was the commonest PONV symptom observed in this study which is in accordance with the study results of Sinha et al.[3] The incidence of nausea was comparable among the groups. Our results are similar to that of other authors and a Meta-analysis who have reported lower efficacy of 5HT3 antagonist for nausea.[1,2,10] Retching was highest in group D (16%) and least in group G (4%). Most of the studies on PONV in patients undergoing craniotomy have not commented on the incidence of retching as a separate symptom.[1,2,3] Post-operative retching is the most neglected PONV symptom, which by causing increase in arterial and intracranial pressure may cause major medical morbidity and therefore should be properly addressed in post craniotomy patients.

The 5HT3 antagonists are relatively recent group of antiemetics with few reported side effects.[6] They do not produce sedation, extrapyramidal reactions or drug interactions with other anesthetic drugs. Most research on 5HT3 antagonists has been performed with ondansetron. The optimal dose range of Ondansetron to prevent PONV is 4-8 mg IV with duration of antiemetic effect being dose related.[13] However as the current authors used ondansetron with dexamethasone which owing to its long half-life (36-72 h) is effective against both early and late emesis,[14] 4 mg was used as the study dose of ondanstron. Granisetron has a longer half-life of 8-9 h versus 3 h for ondansetron and therefore requires less frequent dosing.[15] Granisetron 2 mg has been shown to have similar antiemetic efficacy as ondansetron 8-16 mg following cancer chemotherapy.[15] Bhattacharya and Banerjee found granisetron 2 mg to be more effective than ondansetron 4 mg in preventing PONV following gynecological laparoscopy.[16] Granisetron 1 mg has been shown to provide adequate antiemetic prophylaxis after supratentorial craniotomy;[10] 1 mg was chosen as the study dose of granisetron. With regard to timing, the 5HT3 antagonists and dexamethasone appear to be most effective when administered at the end of surgery and before the induction of anesthesia respectively.[17]

A number of modifications in anesthetic technique such as restricting opioid use to fentanyl, using injection diclofenac and scalp infiltration with bupivacaine to supplement analgesia and propofol as the induction agent were used to reduce the basal incidence of PONV.[17,18,19,20] There is evidence that craniotomy is usually associated with mild pain and less analgesic requirement than other surgical procedures, as was observed in our study.[21] Although, Gan et al. recommended avoiding N2O and minimizing concentration of the volatile anesthetics in order to reduce PONV,[17] we preferred using N2O in lower concentration (50:50) instead of avoiding it so that the concentration of volatile anesthetic agent used did not exceed the minimum alveolar concentration value. A study by Jain et al. found ondansetron and granisetron to be equally effective in preventing emesis following supratentorial craniotomy.[10] The present study also demonstrates that PONV was high but statistically insignificant in Group O (12%) compared with group G (4%) and was significantly increased in patients of group D (48%), compared with above two groups. We evaluated the antiemetic efficacy of the combination for 48 h post-operatively unlike most of the other authors who evaluated it only for first 24 h.[1,8,11,12] However, we could not demonstrate any significant reduction in PONV beyond 24 h post craniotomy. This may be due to the fact that 5HT3 receptor antagonists are the most effective against early vomiting and dexamethasone against both early and late nausea and vomiting.[13,14] The incidence of PONV was found to higher than that of RAE requirement as PONV included all episodes of nausea, whereas RAE was administered only when nausea persisted more than 10 min.

The possible neurosurgical risk factors for PONV such as sex, smoking status, duration of anesthesia, site of lesion and post-operative pain were evaluated and found to be comparable among the groups, therefore not affecting the results.[5,22] Incidence of PONV was found to be significantly increased in patients who underwent surgery for the infratentorial tumors when compared to supratentorial tumors which is in accordance with the study results of Fabling et al.[5] This is in contrast to Kathirvel et al. who found the incidence of PONV to be comparable in supratentorial and infratentorial lesions.[1] Fabling et al. have shown female patients to be more prone to PONV.[5] In the present study, a higher incidence of PONV was observed in female sex in Group D. However, it did not reach statistical significance. An extensive study with a larger sample size is required conclude more definitely on risk factors for PONV following craniotomy.

The three groups were comparable regarding the sedation scores and VAS scores throughout post-operative period. The higher sedation in the first post-operative hour can be explained by the residual effect of general anesthesia. Kathirvel et al. also did not observe excessive sedation after ondansetron treatment. However they did not quantify the level of sedation.[1]

Our study has some limitations. No control group was studied. Second, we did not compare combination of 5HT3 antagonists + dexamethasone with 5HT3 antagonists alone. Dexamethasone, in neurosurgical patients, reduces perilesional edema and is traditionally used in craniotomy. We therefore took group D as our control group. The intra operative use of nitrous oxide, isoflurane and dexamethasone could have influenced the baseline PONV incidence in our study. Future studies investigating administration of 5HT3 antagonist both at the start and end of surgery and combination of pharmacological and non-pharmacological methods could be the strategies to further reduce PONV in these patients.

CONCLUSION

Combination regimen of granisetron or ondansetron in doses of 1 and 4 mg with dexamethasone respectively provide superior and effective antiemetic prophylaxis compared with Dexamethasone alone in adult patients undergoing elective craniotomy without producing any significant side-effects or affecting neurocognitive monitoring which is so essential in post-operative neurosurgical care. We recommend the prophylactic antiemetic combination of granisetron or ondansetron in doses of 1 and 4 mg respectively with dexamethasone for preventing post craniotomy PONV.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kathirvel S, Dash HH, Bhatia A, Subramaniam B, Prakash A, Shenoy S. Effect of prophylactic ondansetron on postoperative nausea and vomiting after elective craniotomy. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2001;13:207–12. doi: 10.1097/00008506-200107000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neufeld SM, Newburn-Cook CV. The efficacy of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting after craniotomy: A meta-analysis. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2007;19:10–7. doi: 10.1097/01.ana.0000211025.41797.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sinha PK, Tripathi M, Ambesh SP. Efficacy of ondansetron in prophylaxis of postoperative nausea and vomiting in patients following infratentorial surgery: A placebo-controlled prospective double-blind study. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 1999;11:6–10. doi: 10.1097/00008506-199901000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Islam S, Jain PN. Post-operative nausea and vomiting: A review article. Indian J Anaesth. 2004;48:253–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fabling JM, Gan TJ, Guy J, Borel CO, el-Moalem HE, Warner DS. Postoperative nausea and vomiting. A retrospective analysis in patients undergoing elective craniotomy. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 1997;9:308–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castle WM, Jukes AJ, Griffiths CJ, Roden SM, Greenstreet YL. Safety of ondansetron. Eur J Anaesthesiol Suppl. 1992;6:63–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson AJ, Diemunsch P, Lindeque BG, Scheinin H, Helbo-Hansen HS, Kroeks MV, et al. Single-dose i.v. granisetron in the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Br J Anaesth. 1996;76:515–8. doi: 10.1093/bja/76.4.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gan TJ, Coop A, Philip BK. A randomized, double-blind study of granisetron plus dexamethasone versus ondansetron plus dexamethasone to prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting in patients undergoing abdominal hysterectomy. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:1323–9. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000180366.65267.F6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dua N, Bhatnagar S, Mishra S, Singhal AK. Granisetron and ondansetron for prevention of nausea and vomiting in patients undergoing modified radical mastectomy. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2004;32:761–4. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0403200605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jain V, Mitra JK, Rath GP, Prabhakar H, Bithal PK, Dash HH. A randomized, double-blinded comparison of ondansetron, granisetron, and placebo for prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting after supratentorial craniotomy. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2009;21:226–30. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0b013e3181a7beaa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Candiotti KA, Nhuch F, Kamat A, Deepika K, Arheart KL, Birnbach DJ, et al. Granisetron versus ondansetron treatment for breakthrough postoperative nausea and vomiting after prophylactic ondansetron failure: A pilot study. Anesth Analg. 2007;104:1370–3. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000261474.85547.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKenzie R, Tantisira B, Karambelkar DJ, Riley TJ, Abdelhady H. Comparison of ondansetron with ondansetron plus dexamethasone in the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 1994;79:961–4. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199411000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tramèr MR, Reynolds DJ, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Efficacy, dose-response, and safety of ondansetron in prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting: A quantitative systematic review of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Anesthesiology. 1997;87:1277–89. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199712000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henzi I, Walder B, Tramèr MR. Dexamethasone for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting: A quantitative systematic review. Anesth Analg. 2000;90:186–94. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200001000-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.del Giglio A, Soares HP, Caparroz C, Castro PC. Granisetron is equivalent to ondansetron for prophylaxis of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: Results of a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Cancer. 2000;89:2301–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001201)89:11<2301::aid-cncr19>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhattacharya D, Banerjee A. Comparison of ondansetron and granisetron for prevention of nausea and vomiting following day care gynaecological laparoscopy. Indian J Anaesth. 2003;47:279–82. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gan TJ, Meyer T, Apfel CC, Chung F, Davis PJ, Eubanks S, et al. Consensus guidelines for managing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2003;97:62–71. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000068580.00245.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.White PF. Prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting – A multimodal solution to a persistent problem. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2511–2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe048099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scuderi PE, James RL, Harris L, Mims GR., 3rd Multimodal antiemetic management prevents early postoperative vomiting after outpatient laparoscopy. Anesth Analg. 2000;91:1408–14. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200012000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Visser K, Hassink EA, Bonsel GJ, Moen J, Kalkman CJ. Randomized controlled trial of total intravenous anesthesia with propofol versus inhalation anesthesia with isoflurane-nitrous oxide: Postoperative nausea with vomiting and economic analysis. Anesthesiology. 2001;95:616–26. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200109000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dunbar PJ, Visco E, Lam AM. Craniotomy procedures are associated with less analgesic requirements than other surgical procedures. Anesth Analg. 1999;88:335–40. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199902000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gan TJ. Postoperative nausea and vomiting – Can it be eliminated? JAMA. 2002;287:1233–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.10.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]